Abstract

Dehydration and malnutrition are common and often underdiagnosed in hospital settings. Multidrug-resistant bacterial infections result in more than 35,000 deaths a year in nosocomial patients. The effect of temporal dietary and water restriction (DWR) on susceptibility to multidrug-resistant pathogens is unknown. We report that DWR markedly increased susceptibility to systemic infection by ESKAPE pathogens. Using a murine bloodstream model of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection, we show that DWR leads to significantly increased mortality and morbidity. DWR causes increased bacterial burden, severe pathology, and increased numbers of phagocytes in the kidney. DWR appears to alter the functionality of these phagocytes and is therefore unable to control infection. Mechanistically, we show that DWR impairs the ability of macrophages to phagocytose multiple bacterial pathogens and efferocytose apoptotic neutrophils. Together, this work highlights the crucial impact that diet and hydration play in protecting against infection.

Dietary and water restriction increases susceptibility to antimicrobial resistant pathogens by disrupting macrophage function.

INTRODUCTION

Dehydration and malnutrition are common and often underdiagnosed in hospital settings. Dehydrated patients are six times more likely to die than those euhydrated (1), while malnutrition is present in 30 to 50% of patients over the age of 60 (2). Malnutrition is associated with high mortality and morbidity, prolonged hospital stays, and increased hospital costs. Antimicrobial resistant (AMR) bacterial infections are now one of the greatest threats to public health and resulted in more than 1.2 million deaths worldwide in 2019 (3). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is one of the most common AMR pathogens and was responsible for more than 10,000 deaths in 2019 (3). MRSA can cause a wide range of infections from mild skin and soft tissue infections to life-threatening conditions such as bacteremia (4). It is one of the most common causes of bloodstream infection (BSI), with a 30-day mortality rate of 20% (5). The burden of MRSA disease is amplified by the fact that resistance has been demonstrated to every licensed antistaphylococcal agent to date (6). Given that AMR infections are prevalent in hospital settings, as are dehydration and malnutrition, we wanted to know whether there was a link between these.

Caloric excess has been linked to systemic low-grade chronic inflammation, exacerbating conditions such as type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease (7, 8). On the other hand, hypocaloric diets or fasting regimens have been associated with improved outcomes of metabolic, autoimmune, and inflammatory diseases such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis (9–11). There have been a limited number of studies in individuals with normal weight on the effect of caloric restriction on inflammation. Prior studies have shown reduced circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines due to religious fasting (12, 13), and 14% caloric restriction was shown to reduce inflammation and increase thymic output (14). Recent studies have shown that fasting or severe calorie restriction can cause marked reduction in the number of lymphocytes and monocytes in peripheral organs and blood, while there is an accumulation of lymphocytes and reduced egress of monocytes in the bone marrow (15–17). A limited number of studies have investigated the effect of temporal dietary and water restriction (DWR) on subsequent infection. In a bloodstream Listeria monocytogenes challenge, no effect of intermittent fasting was observed (16), whereas, in a pneumonia model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa following 24 hours of fasting, fasted mice were more susceptible to infection (18).

The limited studies that have investigated the role of DWR in infection have not focused on hospital-acquired AMR pathogens, which malnourished and dehydrated patients are very susceptible to. In this study, we show that DWR leads to a reversible immune paralysis, whereby mice are acutely sensitive to a range of AMR pathogens. Focusing on MRSA, we demonstrate that DWR results in profound changes to the immune profile of animals, whereby macrophage populations cannot function normally. This macrophage paralysis results in a hypersusceptible host to MRSA infection.

RESULTS

DWR leads to increased susceptibility to HA-MRSA infection

We have previously shown that an indirect consequence of treating mice with oral antibiotics is temporal weight loss due to reduced water and calorie intake (19). Subsequently, mice treated with oral antibiotics were highly susceptible to infection with hospital-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) isolates (19). To directly investigate the role of weight loss in leading to increased susceptibility to HA-MRSA infection, we developed a model of temporal DWR. In this model, mice were given 50% of their normal daily calorie and water intake. Mice were restricted for 10 days, followed by 2 days of food and water ad libitum (Fig. 1A). DWR leads to a significant acute weight loss in DWR mice compared to that in control mice; however, the weight of DWR mice returns normal by day 12, after 2 days of refeeding and hydration (Fig. 1B). Hematocrit levels were measured throughout the treatment period. DWR mice have elevated hematocrit levels at day 4 of treatment, indicative of dehydration (Fig. 1C). Hematocrit levels are lower in DWR mice compared to those in control mice at day 12, due to rehydration (Fig. 1C). All DWR mice challenged with a BSI with the HA-MRSA USA300 strain TH16 succumbed to infection, whereas only 46% of the control animals succumbed to infection (Fig. 1D). DWR mice have increased bacterial burden in multiple organs at 24- and 72-hours after infection compared to control groups (Fig. 1, E and F). The highest bacterial burden was observed in the kidneys. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of kidney tissue from 24- and 72-hours after infection demonstrated increased kidney pathology in DWR mice, indicative of S. aureus abscess formation (Fig. 1G). Fitting with the pathology results, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels (Fig. 1H) and BUN/creatine ratio (Fig. 1I) were elevated in the serum of DWR mice at 24 hours after infection, indicating acute kidney damage.

Fig. 1. DWR leads to increased mortality and pathology from HA-MRSA infection.

Model of DWR (A). Weight of mice during DWR, n = 19 to 25 (B). Hematocrit measurements from 0, 4, and 12 days, n = 10 to 17 (C). Survival curve of mice challenged intravenously with 1 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) of HA-MRSA strain TH16, n = 14 to 15 (D). Bacterial burden from 24 hours (E) and 72 hours (F) after infection, n = 7 to 16. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining from representative kidney sections of infected animals at 0, 24, and 72 hours after infection. Scale bars, 500 μm (G). Serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (H) and BUN/creatine ratio (I), n = 5. Survival of DWR and DWR after 7-day refeeding infected with 1 × 107 CFU of HA-MRSA, n = 5 to 10 (J). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Šídák posttest [(B), (E), and (F)] and log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test [(D) and (J)], Student’s t test [(H) and (I)]. Error bars represent SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. ns, not significant.

The community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) USA300 strain LAC is highly virulent in mice, and, as a result, DWR has no added effect on mortality (fig. S1A). DWR mice infected with the clonal complex 5 (CC5) HA-MRSA clinical isolate, BS_4884 (19–21), were significantly more susceptible to infection compared to control animals (fig. S1B). The DWR model is also applicable to other hospital-associated infections, as DWR mice were highly sensitive to pneumonia infection with HA-MRSA USA300 strain TH16 (fig. S1C). Like the BSI, CA-MRSA LAC was virulent in both control and DWR mice in a pneumonia infection model (fig. S1D). DWR was chosen as the model to pursue rather than dietary or water restriction alone. Although all groups lost weight to similar levels (fig. S2A) and all treatment groups were susceptible to HA-MRSA BSI (fig. S2B), water or caloric restriction alone could not phenocopy the results of DWR together in the context of TH16 pneumonia infection (fig. S2C).

To understand whether the increased susceptibility to HA-MRSA was temporary, DWR mice were given water and food ad libitum for 7 days after restriction and subsequently infected. Mice that were refed and watered for 7 days were no longer sensitive to HA-MRSA BSI, and they mimicked that of control mice (Fig. 1J). These data demonstrate that the susceptibility of DWR animals to nosocomial infection is temporal.

DWR sensitizes mice to a range of AMR pathogens

Given that DWR leads to increased susceptibility to HA-MRSA bloodstream and pneumonia infection, we investigated whether this is also the case for other AMR pathogens, such as members of the ESKAPE group of pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, S. aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, P. aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species). We demonstrate that DWR mice exhibit increased susceptibility to clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae (Fig. 2A), A. baumannii (Fig. 2B), P. aeruginosa (Fig. 2C), and Enterobacter cloacae (Fig. 2D) during BSI. Because nosocomial patients are also susceptible to infection by the yeast Candida albicans (22), we investigated whether the increased susceptibility of DWR mice extended to this pathogen. In a similar manner to the other AMR bacterial pathogens, DWR mice are also hypersusceptible to a BSI with C. albicans (Fig. 2E). Thus, DWR sensitizes the mammalian host to infections with common nosocomial pathogens.

Fig. 2. DWR sensitizes mice to a variety of AMR pathogens.

Survival curve of intravenously infected mice with 5 × 107 CFU of K. pneumoniae (A), A. baumannii (B), P. aeruginosa (C), E. cloacae (D), and C. albicans (E), n = 5 to 10. Statistical analysis was performed using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.005.

DWR causes minimal changes before infection

To understand the cause of the increased pathogen susceptibility in DWR mice, we examined blood chemistry markers in the serum at day 12 after restriction and before infection. There was little difference between control and DWR mice at these time points before infection (fig. S3).

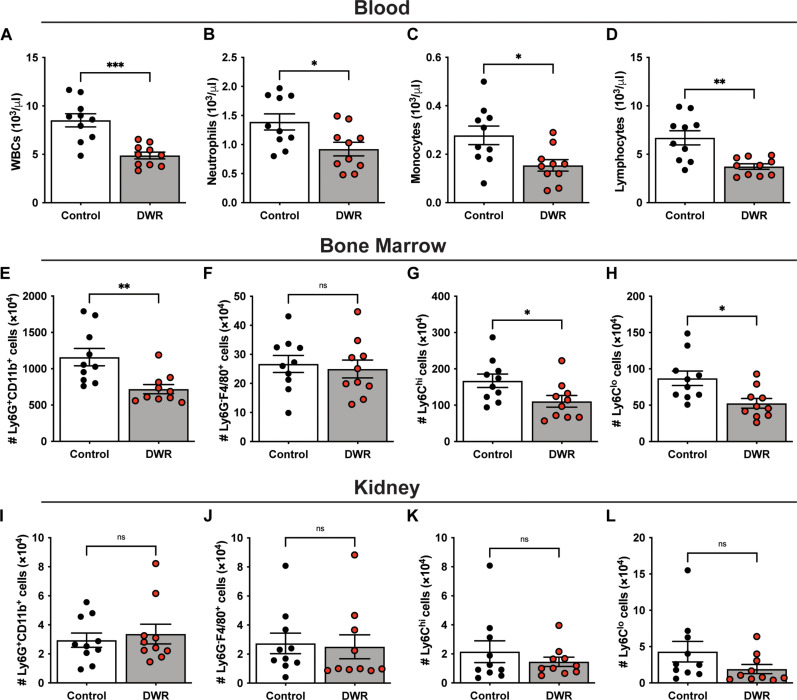

We next analyzed the blood of DWR mice by complete blood count (CBC) at the same time point of day 12 and found that white blood cells (WBCs; Fig. 3A), neutrophils (Fig. 3B), monocytes (Fig. 3C), and lymphocytes (Fig. 3D) were all significantly lower in DWR mice compared to those in control mice. This correlates with published studies that show circulating monocytes (16) and memory T cells (15) are reduced in dietary-restricted mice. Analysis of the cellular population in the bone marrow of DWR mice revealed a significant decrease in the number of neutrophilic (CD11b+Ly6G+) cells compared to that of control mice (Fig. 3E). The level of macrophages (Ly6G−F4/80+) in the bone marrow was very low, and there was no difference between groups (Fig. 3F). Levels of Ly6Chi (Fig. 3G) and Ly6Clo (Fig. 3H) monocytes were reduced in the bone marrow of DWR mice compared to those of control mice. We also analyzed the leukocyte populations in the kidney, and no difference in the numbers of neutrophils, macrophages, or monocytes was observed in the tissues of DWR and control mice (Fig. 3, I to L).

Fig. 3. DWR leads to a reduction in phagocytes in the blood and bone marrow.

Mice were treated with water and caloric restriction for 10 days, followed by 2 days of refeeding. Blood was analyzed for number of white blood cells (WBCs) (A), neutrophils (B), monocytes (C), and lymphocytes (D) by complete blood count (CBC). Bone marrow was analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the number of Ly6G+CD11b+ neutrophils (E), Ly6G−F4/80+ macrophages (F), Ly6Chi monocytes (G), and Ly6Clo monocytes (H). Kidneys were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the number of neutrophils (I), macrophages (J), Ly6Chi monocytes (K), and Ly6Clo monocytes (L). n = 10 per group. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test. The bars represent the mean, and error bars represent SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

We also analyzed serum cytokines before infection at 0 hours (Fig. 4) and found no significant differences between groups in the majority (23 of 25) of cytokines, except for interleukin-5 (IL-5; Fig. 4D) and eotaxin (Fig. 4J), which exhibited a modest increase and are involved in migration and maturation of eosinophils (23). Together with the previous data, these findings suggest that the effect of DWR is not due to altered levels of serum cytokines, serum chemistry markers, or marked changes in leukocytes before infection.

Fig. 4. DWR leads to increased serum cytokine responses.

Serum levels of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) (A), tumor necrosis factor–α (TNFα) (B), interleukin-1β (IL-1β) (C), IL-5 (D), IL-6 (E), IL-10 (F), IL-12 (p70) (G), IL-13 (H), IL-15 (I), eotaxin (J), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) (K), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (L), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1) (M), C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) (N), CCL3 (O), CCL4 (P), leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) (Q), and CXCL2 (R) were analyzed by Luminex assay at time of infection (0 hours) and 4, 24, and 72 hours after infection. n = 9 to 16 per group. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Sidak posttest. The bars represent the mean, and error bars represent SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001.

DWR leads to profound changes in the immune profile of mice after HA-MRSA BSI

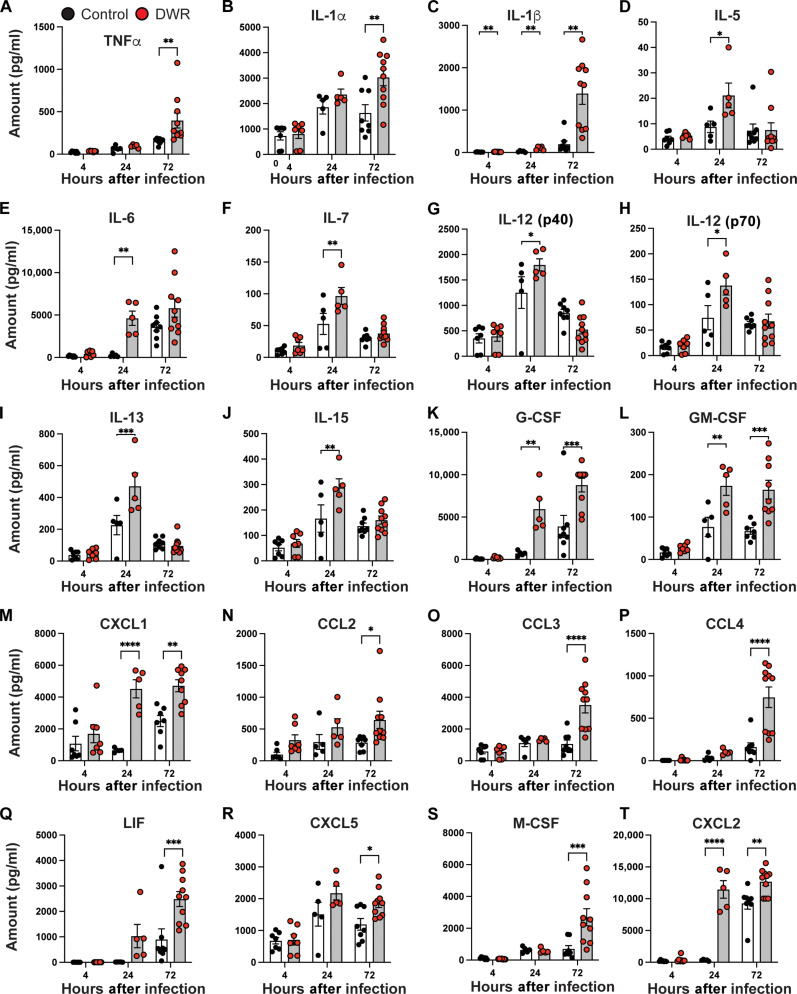

Given that we observed modest changes in the immune profile of mice before infection, we investigated the effect of DWR on host response to HA-MRSA blood stream infection. A robust and broad pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine response was elevated in DWR mice compared to that in control mice. We identified 18 significantly increased serum cytokines when measured at either 4, 24, or 72 hours after infection (Fig. 4, A to R) with a full panel also available (fig. S4). Cytokine and chemokine levels in kidney tissue were also significantly elevated for 20 molecules at 4, 24, and 72 hours after infection in DWR mice compared to those in control mice (Fig. 5, A to T) with a full panel also available (fig. S5).

Fig. 5. DWR leads to increased kidney cytokine responses.

Kidney cytokine levels of TNFα (A), IL-1α (B) IL-1β (C), IL-5 (D), IL-6 (E), IL-7 (F), IL-12 (p40) (G), IL-12 (p70) (H), IL-13 (I), IL-15 (J), G-CSF (K), GM-CSF (L), CXCL1 (M), CCL2 (N), CCL3 (O), CCL4 (P), LIF (Q), CXCL5 (R), M-CSF (S), and CXCL2 (T) were analyzed by Luminex assay at time of infection (0 hours), and 4, 24, and 72 hours after infection with HA-MRSA strain TH16. n = 5 to 10 per group. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Sidak posttest. The bars represent the mean, and error bars represent SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

The number of neutrophils in the blood of MRSA-infected animals was unchanged between the two groups at 24 hours after infection (Fig. 6A). There was a slight increase in the number of macrophages in DWR mice compared to that in control mice; however, the levels were very low overall (Fig. 6B). Ly6Chi monocytes were elevated (Fig. 6C) in DWR mice, whereas there was no difference in Ly6Clo monocytes between groups (Fig. 6D). DWR mice had a reduced number of neutrophils in the bone marrow compared to control mice after infection (Fig. 6E), suggesting that they were being recruited in large numbers to the site of infection. Macrophage (Fig. 6F) and Ly6Clo monocyte (Fig. 6H) numbers were unchanged between the two groups in the bone marrow, while Ly6Chi monocytes were reduced in DWR mice compared to those in control mice (Fig. 6G). In accordance with the histology data (Fig. 1G), the number of neutrophils was significantly higher in kidney tissue from MRSA-infected DWR mice compared to that from control group mice (Fig. 6I). There was no significant difference between the number of macrophages (Fig. 6J) or monocytes (Fig. 6, K and L). Immunofluorescence of kidney sections 72 hours after infection shows larger areas of MRSA fluorescent signal in DWR mice compared to those in control mice (Fig. 6M), which correlates with the increased bacterial burden in the kidney tissue at the same time point (Fig. 1F). In accordance with the flow cytometry data, large aggregates of neutrophils were observed associated with bacterial foci in DWR sections compared to those in sections from control animals. These data are consistent with the significant increase in the level of neutrophil chemoattractants CXCL1 (Fig. 5M) and CXCL2 (Fig. 5T) in DWR mice compared to that in control mice in the kidney tissue.

Fig. 6. Phagocyte numbers 24 hours after infection.

Control and DWR mice infected intravenously with 1 × 107 CFU of HA-MRSA strain TH16. Cells from the blood (A to D), bone marrow (E to H), and the kidneys (I to L) were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the number of Ly6G+CD11b+ neutrophils [(A), (E), and (I)], Ly6G−F4/80+ macrophages [(B), (F), and (J)], Ly6Chi monocytes [(C), (G), and (K)], and Ly6Clo monocytes [(D), (H), and (L)]. n = 10 per group. Kidney sections from 72 hours after infection were stained for S. aureus (green), Ly6G+ cells (red), and F4/80+ cells (blue). Scale bars, 100 μm (M). Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test. The bars represent the mean, and error bars represent SEM. *P < 0.05 and ****P < 0.0001.

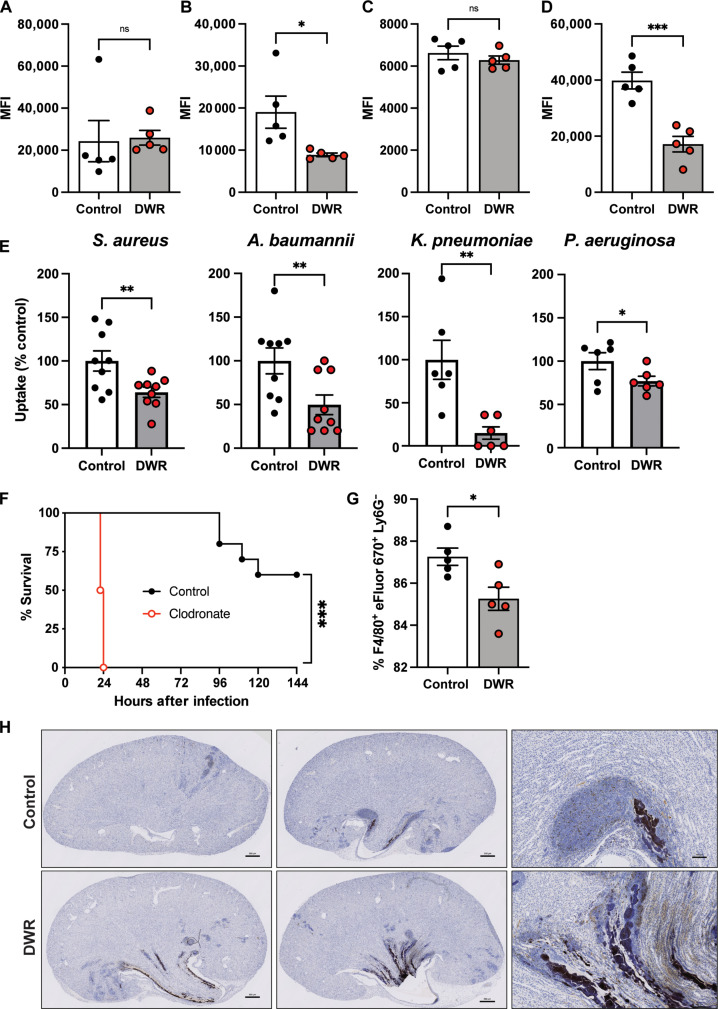

DWR leads to reduced phagocytosis and efferocytosis

We observed many phagocytes present at the site of infection in the kidney of DWR mice; however, there is also a large bacterial burden, suggesting that these phagocytes are unable to deal with the bacteria as well as control mice. To investigate the ability of phagocytic cells to perform their function of clearing bacteria, a phagocytosis assay was used. Bulk bone marrow cells and splenocytes, isolated from DWR and control mice, were infected with green fluorescent protein (GFP)–labeled bacteria, and the level of intracellular phagocytosed bacteria was measured by flow cytometry. There was no difference in the level of phagocytosis between the two groups of bone marrow cells (Fig. 7A), which primarily contain neutrophils (fig. S6A). However, splenocytes, which contain mainly macrophages (24), from DWR mice were unable to phagocytose S. aureus to the same level as control splenocytes (Fig. 7B). To further evaluate the ability of recruited phagocytes to phagocytose S. aureus, we recruited cells to the peritoneal cavity by intraperitoneal instillation of heat-killed S. aureus. Peritoneal exudate cells (PECs) harvested day 1 after recruitment are composed of neutrophils, whereas PECs from day 3 are mainly composed of macrophages (fig. S6B). No difference in the ability of PECs harvested from day 1 was observed between the two groups (Fig. 7C), consistent with the bone marrow data (Fig. 7A). In contrast to day 1 PECs, day 3 PECs from DWR mice exhibited significantly lower levels of phagocytosis compared to cells from control mice (Fig. 7D). Using a gentamicin protection assay, we observed that, in addition to S. aureus, day 3 PECs from DWR mice were impaired in their ability to phagocytose A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa compared to those from control groups (Fig. 7E), indicating that the phenotype is reproducible using other AMR pathogens. These observations suggest that macrophages, rather than neutrophils, are impaired in their ability to phagocytose S. aureus and other pathogens in DWR mice.

Fig. 7. Restriction leads to reduced phagocytosis and efferocytosis.

Bone marrow cells (A), splenocytes (B), and elicited PECs from day 1 (C) and day 3 (D) from control and DWR mice were infected with GFP-labeled S. aureus strain TH16 [multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10], and phgocytosis was assayed using flow cytometry by quantifying the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). n = 5 per group. Gentamicin protection assay of S. aureus strain TH16 and other AMR pathogens (MOI of 10) using day 3 PECs from control or DWR mice. Data normalized to control groups for each bacterium. n = 6 to 9 per group (E). Survival of mice treated with PBS or clodronate liposomes (F), n = 10 per group. Efferocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by PECs from control and DWR mice (G), n = 5 per group. Caspase-3 staining of kidney sections 72 hours after infection. Scale bars, 500 μm (H). Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test [(A) to (D) and (G)], Mann-Whitney one-sided U test (E), and log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (F). Error bars represent SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

To further investigate the importance of phagocytes in the context of DWR and hospital-acquired infections, mice were pretreated with clodronate liposomes that deplete macrophages (25, 26) and arrest certain neutrophil functions (27) and then infected with HA-MRSA. Mice treated with clodronate liposomes were exquisitely sensitive to HA-MRSA infection compared to mice treated with control phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–filled liposomes (Fig. 7F). Given the critical role of macrophages in protecting mice from HA-MRSA and that the number of macrophages in the kidneys of DWR mice remains the same as control mice (Fig. 6J), we postulated that the function of these cells could be impaired in DWR mice. In addition to phagocytosing microbes, macrophages play a critical role in clearing dead cells, a biological process termed efferocytosis, which is key for the resolution of infection (28). We found that macrophages from DWR mice are impaired in their capacity to efferocytose apoptotic neutrophils compared to control macrophages (Fig. 7G). Furthermore, the observed impaired efferocytosis was associated with increased immunohistochemistry staining for the apoptotic marker caspase-3 in the kidneys of HA-MRSA–infected DWR mice compared to that of control mice (Fig. 7H). Together, these data support a model where DWR leads to a reduced ability of macrophages to clear bacteria and apoptotic neutrophils, which contributes to the observed elevated bacterial burden and inflammation in the kidneys.

Serum factors play a role in the restriction phenotype

We posit that the observed increased susceptibility of DWR mice was linked to the systemic presence, or lack thereof, a soluble mediator. To test this hypothesis, a serum transfer experiment was carried out whereby DWR mice received serum from control or DWR mice followed by HA-MRSA BSI. DWR mice that received serum from DWR mice succumbed to infection (Fig. 8A). However, DWR mice that received serum from control mice were significantly protected from HA-MRSA infection (Fig. 8A and fig. S7A). Control mice that received serum from DWR mice were not more susceptible to infection (fig. S7B), suggesting that something present in control serum rather than something present in DWR serum is responsible for the increased susceptibility to HA-MRSA infection.

Fig. 8. Serum factors play a role in the restriction phenotype.

Serum from control or DWR mice was transferred to DWR mice on two consecutive days before intravenous infection with 1 × 107 CFU of TH16, and survival at 150 hours was measured (A), data from four independent experiments with n = 20 per group total. Bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) from naïve mice were treated with serum from control or restricted mice for 2 hours and then infected with GFP-expressing TH16, and intracellular bacteria were measured by plating (B) and flow cytometry (C) 1 hour after infection, n = 10 per group. BMDMs were treated with the metabolite fraction from control or DWR plasma followed by infection with GFP-expressing TH16, and intracellular bacteria were measured by plating (D) and flow cytometry (E), n = 5 per group. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test. Error bars represent SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

To further these findings, we exposed bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) with serum from control or DWR mice and subsequently infected the cells with GFP-labeled MRSA, and intracellular phagocytosed bacteria were quantified by colony-forming unit (CFU) counts (Fig. 8B) and flow cytometry (Fig. 8C). Cells incubated with serum from DWR mice exhibited reduced capacity to phagocytose HA-MRSA compared to cells from control animals. We did not detect differences in the level of serum chemistry analytes (fig. S3) or cytokines (Fig. 4), suggesting that the factor was not detected in our screens.

Next, we performed an organic solvent protein precipitation on control and DWR plasma to generate a metabolite fraction composed of low–molecular weight compounds. BMDMs were then incubated with the plasma metabolite extracts of control or DWR mice, and phagocytosis of bacteria was measured. Both CFU counts of intracellular bacteria (Fig. 8D) and the percentage of GFP+ cells (Fig. 8E) were decreased in samples treated with metabolite fraction from DWR serum compared to those from control serum, indicating that the observed decreased phagocytosis phenotype was due to a metabolite(s). Together, these findings demonstrate that the susceptibility and macrophage dysfunction observed in DWR mice can be traced to the plasma and more specifically metabolites present in control mice.

DISCUSSION

Malnutrition is a common medical problem that affects about half of all patients admitted to acute hospital settings (29, 30). Malnutrition increases the risk of nosocomial infections, negative health outcomes, and complications (31, 32). Studies have found that the prevalence of malnutrition in hospitalized patients is between 20 and 50%, and this variation depends upon geographic location and the populations studied (33). A study from the UK showed that 45% of patients over the age of 65 were dehydrated within 48 hours of hospital admission (1, 34). Malnutrition is often present upon hospital admission; however, it is common for well-nourished and malnourished inpatients to develop malnutrition or suffer further deterioration of nutritional status during hospitalization (35–37). Unfortunately, this often goes unrecognized by healthcare providers. Moreover, the impact of malnutrition and dehydration on the host’s susceptibility to infection is poorly understood. To tackle this, we described here the implementation of a model of DWR. Mice under DWR lost ~20% of their initial weight in the first 10 days. Once DWR mice were provided food and water ad libitum after the restriction period, they rapidly regained weight to the level of control mice. DWR results in a host that is highly susceptible to a range of AMR nosocomial pathogens in a temporal manner. AMR pathogens pose a tremendous threat to global human health, and it has been estimated that 10 million lives will be lost to AMR by 2050 (38). Thus, the DWR model should enable future work on nosocomial pathogens in a susceptible host.

Acute infections are associated with a collection of stereotypical behavioral responses that include lethargy, altered sleep patterns, depression, social withdrawal, and anorexia. Anorexia induced by infection is a conserved aspect of sickness behavior across species (39). It has been shown that mice eat significantly less food when infected with L. monocytogenes, and force-feeding infected mice led to higher mortality rates (40, 41). Wang et al. (42) determined that glucose was the component that mediates lethality during L. monocytogenes infections when anorexia is blocked by force feeding. Although fasting metabolism was protective against bacterial infection, this was not the case for infection with influenza (42). In Drosophila, infection-induced anorexia is beneficial for survival against Salmonella typhimurium infection, is detrimental to survival against L. monocytogenes, and had no effect on survival against Enterococcus faecalis (43). These results highlight the complex relationship between diet restriction and immunity and suggest that pathogens may need to be evaluated on a pathogen-by-pathogen basis. Although these studies focused on dietary restriction, they did so in the context of infection (i.e., restriction after infection), whereas the work presented herein is due to DWR before infection, so direct correlations are not possible.

Our work shows that DWR leads to rapid mortality following HA-MRSA bloodstream and pneumonia infections. This leads to elevated bacterial burdens in multiple organs, with the highest burden seen in the kidneys. The kidney is the main site of infection with large staphylococcal abscesses (44). DWR mice exhibit a pronounced pro-inflammatory cytokine response after HA-MRSA infection, as evidenced by increased cytokines and chemokines systemically in circulation in the serum and locally at the site of infection in the kidney. Sun et al. (45) found that calorie-restricted mice succumbed to polymicrobial infection caused by cecal ligation and puncture significantly quicker than control mice, like the effect that we show with multiple AMR pathogens. Levels of IL-6 and IL-12 were also elevated after polymicrobial infection (45), which complements the highly pro-inflammatory cytokine response we see in DWR mice. We observed elevated serum and kidney cytokine responses, many of which are also increased during sepsis, such as interferon-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-17, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, among others (46). Unexpectedly, our DWR model caused minimal changes in serum chemistry or serum cytokine levels before infection. These results were recorded after 2 days of feeding ad libitum, which may be responsible for the levels of many of these readouts returning to homeostatic levels. The observed increased susceptibility to HA-MRSA was temporal, and mice that were refed and rehydrated for 7 days after DWR were no longer more susceptible compared to control animals.

Recent studies have begun to shed light on the immune processes that occur during caloric restriction. T lymphocytes relocate from the secondary lymphoid organs to the bone marrow, whereby they adopt a state associated with energy conservation in dietary-restricted mice receiving 50% of their daily food intake (15). In a different model of dietary restriction, whereby mice were fasted for 36 hours, germinal center B cells undergo apoptosis, while naïve B cells leave the Peyer’s patches, migrating to the bone marrow and only egressing upon refeeding (17). In yet another model of caloric restriction, fasting reduced the number of circulating monocytes in mice and humans by preventing their mobilization from the bone marrow (16). Monocytes have also been shown to migrate to the bone marrow upon fasting, and refeeding resulted in a surge of monocytes back into circulation with a deleterious effect on the host response to bacterial infection (18). Although work has been done on caloric restriction, there is no unified model of restriction protocols, and, therefore, it makes comparisons between studies difficult.

We show that peritoneal macrophages from DWR mice had reduced ability to phagocytose MRSA along with other bacterial pathogens, providing insight into the severe susceptibility that these mice have to AMR pathogen infections. These data are in line with previous work in which peritoneal macrophages from calorie-restricted mice exhibited reduced phagocytic function (as measured by the uptake of fluorescence-labeled beads) compared to controls (45). Jordan et al. (16) found that monocytes from fasted animals had 2700 differentially expressed genes compared with control monocytes, resulting in a quiescent metabolic phenotype. In a model of adult autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, recurrent dehydration caused macrophages to manifest an M2 phenotype (47). This more anti-inflammatory macrophage state may be occurring in the DWR mice, leading to the reduced ability to deal with infection. A study where mice were starved for 24 to 48 hours caused a decrease in the pulmonary clearance of S. aureus primarily due to the impairment of the bactericidal action of macrophages (48).

We hypothesize that DWR results in a state of immune paralysis, whereby macrophages are temporally impaired in performing their normal functions. To further support the idea of immune paralysis, macrophages from DWR mice recruited to the peritoneal cavity were defective in their ability to efferocytosis apoptotic neutrophils. Efferocytosis is the effective clearance of apoptotic cells by professional and nonprofessional phagocytes (49). The decreased level of efferocytosis in DWR mice may explain the increased numbers of neutrophils in the kidneys of these mice, as they are not being cleared as effectively as in control animals. In addition, caspase-3, which degrades multiple cellular proteins and is responsible for morphological changes and DNA fragmentation in cells during apoptosis (50), was more prevalent in kidney sections from DWR mice compared to that from control mice. This suggests that apoptotic neutrophils are not being effectively cleared in DWR mice. Neutrophils are considered the first immune cell to reach the site of an S. aureus infection, whereas monocytes (which may differentiate into macrophages) are usually attracted later (51). During intravenous infection, MRSA is primarily sequestered and killed by the tissue resident intravascular Kupffer cells in the liver (26). Typically, a small number of bacteria can survive intracellularly, ultimately escaping to form micro-abscesses in the liver, and extracellular S. aureus may disseminate to seed kidney abscesses (44), as we see in our model. It is likely that DWR impairs the function of the tissue resident macrophages to act as gate keeper cells during infection (26, 52), leading to the increase in bacterial burden in the peripheral organs of DWR mice. DWR mice succumb to HA-MRSA BSI quickly, and this rapid mortality could be recapitulated when mice are depleted of macrophages. Together, DWR leads to impairment of macrophages to perform phagocytosis and efferocytosis.

The transfer of control serum into DWR mice resulted in increased survival compared to mice that received DWR serum, indicating that a factor(s) in the serum may be responsible for the phenotype. Treatment of BMDMs with serum or the metabolite fraction from control or DWR plasma was sufficient to induce differential phagocytic responses. Thus, a metabolite or multiple metabolites in the serum are responsible for the observed blunted phagocytic activity of the macrophages. It is likely a component present in control serum, but absent in DWR, as the serum transfer of DWR serum in control mice did not cause a decrease in survival. Future work will be aimed at identifying the effector metabolite(s) and the molecular means by which it drives macrophage dysfunction.

Overall, we described the development of the DWR murine model to study the pathogenesis of nosocomial microbes. We show that DWR results in a hypersusceptibility to infection with AMR pathogens due to an impairment of macrophage function. This work highlights the importance of correct nutrition and hydration in nosocomial settings and the importance of macrophages as gatekeepers.

METHODS

Bacteria strains and growth conditions

All strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. aureus strains were grown on tryptic soy agar (TSA) or in tryptic soy broth (TSB). S. aureus cultures were grown in 5 ml of medium in 15-ml tubes shaking with a 45° angle at 37°C. For all experiments, S. aureus was grown in TSB overnight, and a 1:100 dilution of overnight cultures was subcultured into fresh TSB. S. aureus grown to early stationary phase (3 hours) was collected and normalized by optical density (OD) at 600 nm for further experimental analysis.

Table 1. Strains used in this study.

| Strain no. | Strain description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| VJT 12.61 | S. aureus USA300 strain LAC. This is a highly cytotoxic CA-MRSA CC8 clinical isolate. | (60) |

| VJT 43.92 | S. aureus USA300 strain TH16. This is a low cytotoxic and epidemiologically HA-MRSA CC8 clinical isolate. | (20, 21) |

| VJT 64.01 | S. aureus strain BS_4884. This is a low cytotoxic and epidemiologically HA-MRSA CC5 clinical isolate. | (20, 21) |

| VJT 75.46 | S. aureus TH16 pOS1-GFP | This study |

| VJT 72.17 | K. pneumoniae 161. Clinical isolate | (19) |

| VJT 72.18 | E. cloacae 173. Clinical isolate | (19) |

| VJT 72.21 | P. aeruginosa 192. Clinical isolate | (19) |

| VJT 72.23 | A. baumannii 161. Clinical isolate | (19) |

| VJT 75.25 | C. albicans SC5314 | (61) |

| VJT 31.58 | S. aureus Newman ΔΔΔΔ (ΔlukED ΔhlgACB::tet ΔlukAB::spec Δhla::ermC) | (62) |

Other ESKAPE microbes were grown overnight in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth and subcultured into fresh BHI broth at a 1:100 dilution and grown for 3 hours. C. albicans was grown overnight in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose medium and diluted to a final concentration of 5 × 106 CFU/ml.

Mice

All experiments involving animals were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of New York University (NYU) Langone Health (IA16-00050) and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (no. 3214) and were performed according to the guidelines from the National Institutes of Health, the Animal Welfare Act, and US Federal Law. Mice were housed in specific pathogen–free facilities. Female C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (strain no. 000664) at 6 to 8 weeks of age and were randomly assigned to groups of infection.

DWR model

The daily intake of regular chow (PicoLab Rodent Diet 20, no. 5053) and water by mice was determined by giving a defined amount of food and water and measuring the remainder daily for 2 weeks. Mice were provided with 50% of their daily food and 50% of their daily water every 24 hours. Water was provided in gel form. Mice were placed on DWR diet for 10 days, after which, water and food were provided ad libitum.

In vivo infections

S. aureus strains and other AMR pathogens were grown in TSB or BHI, respectively, at 1:100 from overnight cultures for 3 hours at 37°C with shaking. Microbes were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min, washed two times with 1× PBS, OD-normalized, and diluted to the indicated inoculum in 1× PBS for infection. Mice were anesthetized with Avertin (2,2,2-tribromoethanol dissolved in tert-amyl alcohol and diluted to a final concentration of 2.5% v/v in 0.9% sterile saline) by intraperitoneal injection. For the BSI model, mice were challenged with 1 × 107 CFU by retro-orbital injection (intravenous) for S. aureus infections and 5 × 107 CFU for the other AMR pathogens. For the pneumonia infection model, mice were challenged with 4 × 108 CFU by intranasal instillation of S. aureus. Signs of morbidity (>30% weight loss, ruffled fur, hunched posture, paralysis, inability to walk, or inability to consume food or water) were monitored after infection.

To evaluate bacterial burden in organs, infected mice were euthanized, and the indicated organs collected in 1 ml of PBS and homogenized to enumerate bacterial burden. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture and anticoagulated using heparin-coated tubes (BD Microtainer, no. 365965). Hematocrit levels were measured by CBCs using a HESKA Element HT5.

For the serum transfer studies, mice were placed on DWR diet for 10 days, after which water and food were provided ad libitum. On day 11 and day 12, 250 μl of control or restriction serum was administered intraperitoneally, and mice were subsequently challenged on day 13.

Cytokine quantification

For serum, blood was collected in serum separator tubes (BD Biosciences), allowed to coagulate at room temperature (RT) for 30 min, and then centrifuged for 4 min at 15,000 rpm. For kidney tissue, Halt protease inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 78439) was added to kidney homogenate (described above). Samples were stored at −80°C until use. Cytokine quantification was determined using the MILLIPLEX MAP Mouse Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Kit (MCYTMAG-70 K-PX32, Millipore). The assay was conducted as per the manufacturer’s instructions, and plates were run on a MAGPIX instrument with xPONENT software.

PEC preparation

To generate PECs, mice were injected intraperitoneally with heat-killed 1 × 107 CFU of heat-killed S. aureus Newman ΔΔΔΔ (VJT 31.58) as described previously (53). PECs were harvested by lavage of the peritoneal cavity with 5 ml of PBS.

Primary mouse BMDMs

Bulk mouse bone marrow cells were obtained by centrifuging the femur and tibia at 10,000 rpm for 2 min at RT. Cell pellets were resuspended in PBS and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min at RT. Then, cells were washed once with PBS and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min at RT. Red blood cells were lysed using 1 ml of PharmLyse (BD Biosciences) at RT for 5 min. Ten milliliters of PBS was added immediately and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min at RT. Then, cells were resuspended in 5 ml of PBS, strained using 100-μm cell strainer, and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min at RT. Cell pellets were resuspended in RPMI 1640 Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and counted. Bone marrow cells were differentiated into BMDMs as previously described (54).

Phagocytosis assays

For all phagocytosis assays, bulk bone marrow cells, PECs, or splenocytes were plated at 1 × 105 cells per well in 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. For experiments involving BMDMs, cells were pretreated with serum or metabolite fractions harvested from DWR or control mice (20% v/v) for 2 hours followed by replacing each well with fresh RPMI 1640 Medium. GFP-labeled S. aureus was added to the wells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 and incubated for 1 hour. After this, lysostaphin (10 μg per well; Ambi, NY) was added for 10 min at 37°C to kill any remaining extracellular S. aureus. For flow cytometry analysis, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) fixation buffer was added and samples were analyzed using a CytoFlex cytometer. For CFU analysis, cells were washed twice with PBS, lifted off the plate by mechanical disruption, serially diluted, and plated on TSA.

To quantify phagocytic update of other bacterial pathogens, a gentamicin protection assay was used. After seeding day 3 PECs and resting for 30 min, bacteria were added at an MOI of 10 and co-incubated for 30 min. A concentrated gentamicin stock was added to the infection for an additional 30 min to eliminate extracellular bacteria. The final concentration of gentamicin varied between pathogen (A. baumannii and K. pneumoniae, 5 μg/ml; P. aeruginosa, 30 μg/ml; and S. aureus, 60 μg/ml). Cells were then washed with PBS two times, scraped off the plate, and serially diluted to enumerate intracellular CFUs.

Macrophage efferocytosis assay

Murine PECs were harvested 3 days after HK-S. aureus injection. Cells were stained with cell proliferation dye eFluor 670 (eBioscience, 65-0840-85) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Apoptotic neutrophils were generated by plating at 37°C for 24 hours as previously described (55, 56). To determine efferocytic capacity of macrophages, peritoneal elicited macrophages were cultured for 30 min with apoptotic neutrophils at 37°C in a 1:10 ratio in complete culture medium [RPMI 1640 Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin]. Following efferocytosis, cell suspensions were stained with antibodies against CD45, F4/80, and Ly6G. Cells were analyzed using a CtyoFlex cytometer. Efferocytosis of apoptotic polymorphonuclear neutrophils was determined by gating on Ly6G− cells within the F4/80+eFluor 670+ population.

Macrophage depletion

Macrophage depletion was achieved by intravenous injection of clodronate-containing liposomes (1 mg of clodronate per mouse) or PBS liposomes (Liposoma) 24 hours before challenge with TH16.

Serum chemistry analysis

Serum samples were prepared as described above and sent to IDEXX BioAnalytics for comprehensive chemistry analyses.

Blood cell analysis

Levels of WBCs, neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes from blood samples were measured by CBCs using a HESKA Element HT5.

Flow cytometry analysis

To assess cell populations in bone marrow, kidney, and blood, single-cell suspensions were prepared as previously described (54, 57). For flow cytometry staining, cells were incubated with Fc block (anti-mouse CD16/32, clone 24G2; Bio X Cell) in FACS buffer (2% FBS and 0.05% sodium azide in PBS) for 10 min on ice. Cells were stained with Peridinin chlorophyll protein-Cyanine5.5, CD45 (30-F11; BD Biosciences), V500 CD11b (M1/70; BD Biosciences), fluorescein isothiocyanate Ly6G (1A8; BD Biosciences), BV605 TCRβ (H57-597; Biolegend), and PacBlue B220 (RA3-6B2; Biolegend) for 20 min on ice. Cells were washed and incubated with LIVE/DEAD Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain (Invitrogen, L34961) for 20 min on ice. Cells were washed twice with FACS buffer and fixed with 200 μl of FACS fixation buffer (2% paraformaldehyde in FACS buffer). Data were acquired using the Cytoflex instrument (Beckman Coulter). Neutrophils were gated as live, single, TCRβ−B220−, CD45+, and Ly6G+CD11b+ cells.

Histology

Kidney tissue was harvested and placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (VWR) for 72 hours. Tissue was processed by the NYU Experimental Pathology Research Laboratory. Tissues were processed into formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks using a Leica Peloris automated tissue processor. Paraffin sections (5 μM) were stained with H&E and caspase-3 on a Leica BondRX autostainer, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were imaged on a Hamamatsu Nanozoomer whole slide scanner.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Tissues were processed as previously described (57–59). Sections were blocked with anti-CD16/CD32 (BioLegend, clone 93, 1:200) diluted in 1× PBS and 0.1% Triton X-100, 2% FBS, and 2% goat serum for 1 hour RT. Sections were then incubated with F4/80 (Allophycocyanin, BM8, BioLegend, 1:100), Ly6G (Phycoerythrin, 1A8, BioLegend, 1:100), and anti–S. aureus (rabbit, polyclonal, Abcam, 1:300) in staining medium for 1 hour at RT. Slides were washed with PBS and then stained with goat anti-rabbit secondary staining (AF488, Invitrogen, 1:300) in staining medium for 1 hour at RT. Sections were cover slipped using Immu-Mount mounting medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA) and cover glasses with a 0.13- to 0.17-mm thickness (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA). Fluorescence was detected with a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with 405-, 488-, 514-, 561-, 594-, and 633-nm solid-state laser lines, a 32-channel spectral detector (409 to 695 nm), and 10× 0.3 numerical aperture (NA), 20× Plan-Apochromat 0.8 NA, 40×, and 63× 1.40 NA objectives. Zen Black (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) software suite was used for data collection. The imaging data were processed and analyzed using Imaris software version 9.0.2 (Bitplane USA; Oxford Instruments, Concord, MA, USA). Images were filtered with the 3 × 3 × 1 median filter function to reduce background autofluorescence.

Metabolite extraction

Blood was collected by cardiac puncture and anticoagulated using K2EDTA coated tubes (BD Microtainer, no. 364974). Samples were centrifuged at 3000g for 10 min at 4°C. Plasma was removed and kept frozen until extraction and then thawed. Plasma was combined with methanol buffer on dry ice. Samples were homogenized in a BeadBlaster (Benchmark Scientific) using 100 μl of zircon beads (Research Products International) (0.5 mm) and centrifuged at 21,000g for 3 min at 4°C. Then, 450 μl of the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and dried down by speed vacuum concentration to completion. Last, dried metabolite extracts were reconstituted in 50 μl of liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry–grade water, sonicated for 2 min, and kept frozen until analysis.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9 was used for all statistical analyses. All the statistical details of experiments can be found in the figure legends. Unless stated otherwise, each experiment was carried out using biological replicates over multiple days.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Torres laboratory for insightful discussions and comments on this manuscript. We thank K. Moore for the use of the CBC machine.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases award numbers AI149350 and AI137336 to V.J.T., Cystic Fibrosis Foundation award LACEY19FO to K.A.L., and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities to V.J.T. Cell sorting/flow cytometry technologies were provided by NYU Langone’s Cytometry and Cell Sorting Laboratory and the histology was processed by NYU Langone’s Experimental Pathology Research Laboratory. These cores are supported, in part, by the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center support grant P30CA016087 from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute.

Author contributions: K.A.L. and V.J.T. designed the study. K.A.L., A.M.P., S.G., and A.H.C. performed experiments. E.B. performed immunofluorescence, and T.C.R. performed metabolite extraction. A.M.P. and A.H.C. performed all the revisions. D.R.J., K.M.K., and V.J.T. managed the project. K.A.L. and V.J.T. wrote the initial manuscript and A.M.P. and A.H.C. revised the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Competing interests: V.J.T. has consulted for Janssen Research & Development LLC and has received honoraria from Genentech and Medimmune. He is also an inventor on patents and patent applications filed by New York University, which are now under commercial license to Janssen Biotech Inc. Janssen Biotech Inc. provides research funding and other payments associated with a licensing agreement. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S7

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.El-Sharkawy A. M., Watson P., Neal K. R., Ljungqvist O., Maughan R. J., Sahota O., Lobo D. N., Hydration and outcome in older patients admitted to hospital (The HOOP prospective cohort study). Age Ageing 44, 943–947 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silver H. J., Pratt K. J., Bruno M., Lynch J., Mitchell K., McCauley S. M., Effectiveness of the malnutrition quality improvement initiative on practitioner malnutrition knowledge and screening, diagnosis, and timeliness of malnutrition-related care provided to older adults admitted to a tertiary care facility: A pilot study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 118, 101–109 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators, Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 629–655 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong S. Y. C., Davis J. S., Eichenberger E., Holland T. L., Fowler V. G., Staphylococcus aureus infections: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 603–661 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Hal S. J., Jensen S. O., Vaska V. L., Espedido B. A., Paterson D. L., Gosbell I. B., Predictors of mortality in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 25, 362–386 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stryjewski M. E., Corey G. R., Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: An evolving pathogen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58, S10–S19 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lumeng C. N., Saltiel A. R., Inflammatory links between obesity and metabolic disease. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 2111–2117 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haslam D. W., James W. P., Obesity. Lancet 366, 1197–1209 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi I. Y., Piccio L., Childress P., Bollman B., Ghosh A., Brandhorst S., Suarez J., Michalsen A., Cross A. H., Morgan T. E., Wei M., Paul F., Bock M., Longo V. D., A diet mimicking fasting promotes regeneration and reduces autoimmunity and multiple sclerosis symptoms. Cell Rep. 15, 2136–2146 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen P., Christensen R., Zachariae C., Geiker N. R. W., Schaadt B. K., Stender S., Hansen P. R., Astrup A., Skov L., Long-term effects of weight reduction on the severity of psoriasis in a cohort derived from a randomized trial: A prospective observational follow-up study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 104, 259–265 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kjeldsen-Kragh J., Borchgrevink C. F., Laerum E., Haugen M., Eek M., Førre O., Mowinkel P., Hovi K., Controlled trial of fasting and one-year vegetarian diet in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 338, 899–902 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aksungar F. B., Topkaya A. E., Akyildiz M., Interleukin-6, C-reactive protein and biochemical parameters during prolonged intermittent fasting. Ann. Nutrit. Metab. 51, 88–95 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faris M. A.-I. E., Kacimi S., Al-Kurd R. A., Fararjeh M. A., Bustanji Y. K., Mohammad M. K., Salem M. L., Intermittent fasting during Ramadan attenuates proinflammatory cytokines and immune cells in healthy subjects. Nutr. Res. 32, 947–955 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spadaro O., Youm Y., Shchukina I., Ryu S., Sidorov S., Ravussin A., Nguyen K., Aladyeva E., Predeus A. N., Smith S. R., Ravussin E., Galban C., Artyomov M. N., Dixit V. D., Caloric restriction in humans reveals immunometabolic regulators of health span. Science 375, 671–677 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins N., Han S. J., Enamorado M., Link V. M., Huang B., Moseman E. A., Kishton R. J., Shannon J. P., Dixit D., Schwab S. R., Hickman H. D., Restifo N. P., McGavern D. B., Schwartzberg P. L., Belkaid Y., The bone marrow protects and optimizes immunological memory during dietary restriction. Cell 178, 1088–1101.e15 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jordan S., Tung N., Casanova-Acebes M., Chang C., Cantoni C., Zhang D., Wirtz T. H., Naik S., Rose S. A., Brocker C. N., Gainullina A., Hornburg D., Horng S., Maier B. B., Cravedi P., LeRoith D., Gonzalez F. J., Meissner F., Ochando J., Rahman A., Chipuk J. E., Artyomov M. N., Frenette P. S., Piccio L., Berres M. L., Gallagher E. J., Merad M., Dietary intake regulates the circulating inflammatory monocyte pool. Cell 178, 1102–1114.e17 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagai M., Noguchi R., Takahashi D., Morikawa T., Koshida K., Komiyama S., Ishihara N., Yamada T., Kawamura Y. I., Muroi K., Hattori K., Kobayashi N., Fujimura Y., Hirota M., Matsumoto R., Aoki R., Tamura-Nakano M., Sugiyama M., Katakai T., Sato S., Takubo K., Dohi T., Hase K., Fasting-refeeding impacts immune cell dynamics and mucosal immune responses. Cell 178, 1072–1087.e14 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janssen H., Kahles F., Liu D., Downey J., Koekkoek L. L., Roudko V., D’Souza D., McAlpine C. S., Halle L., Poller W. C., Chan C. T., He S., Mindur J. E., Kiss M. G., Singh S., Anzai A., Iwamoto Y., Kohler R. H., Chetal K., Sadreyev R. I., Weissleder R., Kim-Schulze S., Merad M., Nahrendorf M., Swirski F. K., Monocytes re-enter the bone marrow during fasting and alter the host response to infection. Immunity 56, 783–796.e7 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacey K. A., Gonzalez S., Yeung F., Putzel G., Podkowik M., Pironti A., Shopsin B., Cadwell K., Torres V. J., Microbiome-independent effects of antibiotics in a murine model of nosocomial infections. MBio 13, e0124022 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rose H. R., Holzman R. S., Altman D. R., Smyth D. S., Wasserman G. A., Kafer J. M., Wible M., Mendes R. E., Torres V. J., Shopsin B., Cytotoxic virulence predicts mortality in nosocomial pneumonia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis 211, 1862–1874 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wunderink R. G., Niederman M. S., Kollef M. H., Shorr A. F., Kunkel M. J., Baruch A., McGee W. T., Reisman A., Chastre J., Linezolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: A randomized, controlled study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54, 621–629 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pappas P. G., Lionakis M. S., Arendrup M. C., Ostrosky-Zeichner L., Kullberg B. J., Invasive candidiasis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 4, 18026 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mould A. W., Matthaei K. I., Young I. G., Foster P. S., Relationship between interleukin-5 and eotaxin in regulating blood and tissue eosinophilia in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 99, 1064–1071 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hensel J. A., Khattar V., Ashton R., Ponnazhagan S., Characterization of immune cell subtypes in three commonly used mouse strains reveals gender and strain-specific variations. Lab. Invest. 99, 93–106 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown A. F., Murphy A. G., Lalor S. J., Leech J. M., O’Keeffe K. M., Mac Aogáin M., O’Halloran D. P., Lacey K. A., Tavakol M., Hearnden C. H., Fitzgerald-Hughes D., Humphreys H., Fennell J. P., van Wamel W. J., Foster T. J., Geoghegan J. A., Lavelle E. C., Rogers T. R., McLoughlin R. M., Memory Th1 cells are protective in invasive Staphylococcus aureus infection. PLOS Pathog. 11, e1005226 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surewaard B. G., Deniset J. F., Zemp F. J., Amrein M., Otto M., Conly J., Omri A., Yates R. M., Kubes P., Identification and treatment of the Staphylococcus aureus reservoir in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 213, 1141–1151 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Culemann S., Knab K., Euler M., Wegner A., Garibagaoglu H., Ackermann J., Fischer K., Kienhöfer D., Crainiciuc G., Hahn J., Grüneboom A., Nimmerjahn F., Uderhardt S., Hidalgo A., Schett G., Hoffmann M. H., Krönke G., Stunning of neutrophils accounts for the anti-inflammatory effects of clodronate liposomes. J. Exp. Med. 220, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boada-Romero E., Martinez J., Heckmann B. L., Green D. R., The clearance of dead cells by efferocytosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 398–414 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edington J., Boorman J., Durrant E. R., Perkins A., Giffin C. V., James R., Thomson J. M., Oldroyd J. C., Smith J. C., Torrance A. D., Blackshaw V., Green S., Hill C. J., Berry C., McKenzie C., Vicca N., Ward J. E., Coles S. J., Prevalence of malnutrition on admission to four hospitals in England. The Malnutrition Prevalence Group. Clin Nutr 19, 191–195 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim S. L., Ong K. C. B., Chan Y. H., Loke W. C., Ferguson M., Daniels L., Malnutrition and its impact on cost of hospitalization, length of stay, readmission and 3-year mortality. Clin. Nutr. 31, 345–350 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Correia M. I., Waitzberg D. L., The impact of malnutrition on morbidity, mortality, length of hospital stay and costs evaluated through a multivariate model analysis. Clin. Nutr. 22, 235–239 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider S. M., Veyres P., Pivot X., Soummer A. M., Jambou P., Filippi J., van Obberghen E., Hébuterne X., Malnutrition is an independent factor associated with nosocomial infections. Br. J. Nutr. 92, 105–111 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabashneh S., Alkassis S., Shanah L., Ali H., A complete guide to identify and manage malnutrition in hospitalized patients. Cureus 12, e8486 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shells R., Morrell-Scott N., Prevention of dehydration in hospital patients. Br. J. Nurs. 27, 565–569 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell J., Bauer J., Capra S., Pulle C. R., Barriers to nutritional intake in patients with acute hip fracture: Time to treat malnutrition as a disease and food as a medicine? Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 91, 489–495 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braunschweig C., Gomez S., Sheean P. M., Impact of declines in nutritional status on outcomes in adult patients hospitalized for more than 7 days. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 100, 1316–1322 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirkland L. L., Shaughnessy E., Recognition and prevention of nosocomial malnutrition: A review and a call to action!. Am. J. Med. 130, 1345–1350 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.J. O'Neill, “Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: Final report and recommendations.” Rev. Antimicrob. Resist. (2016).

- 39.Adamo S. A., Parasitic suppression of feeding in the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta: Parallels with feeding depression after an immune challenge. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 60, 185–197 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray M. J., Murray A. B., Anorexia of infection as a mechanism of host defense. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 32, 593–596 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wing E. J., Young J. B., Acute starvation protects mice against Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 28, 771–776 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang A., Huen S. C., Luan H. H., Yu S., Zhang C., Gallezot J. D., Booth C. J., Medzhitov R., Opposing effects of fasting metabolism on tissue tolerance in bacterial and viral inflammation. Cell 166, 1512–1525.e12 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ayres J. S., Schneider D. S., The role of anorexia in resistance and tolerance to infections in Drosophila. PLOS Biol. 7, e1000150 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng A. G., Kim H. K., Burts M. L., Krausz T., Schneewind O., Missiakas D. M., Genetic requirements for Staphylococcus aureus abscess formation and persistence in host tissues. FASEB J. 23, 3393–3404 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun D., Muthukumar A. R., Lawrence R. A., Fernandes G., Effects of calorie restriction on polymicrobial peritonitis induced by cecum ligation and puncture in young C57BL/6 mice. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8, 1003–1011 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chousterman B. G., Swirski F. K., Weber G. F., Cytokine storm and sepsis disease pathogenesis. Semin. Immunopathol. 39, 517–528 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Y., Zhou J., Zhang D., Lv J., Chen M., Wang C., Song M., He F., Song S., Mei C., Dehydration accelerates cytogenesis and cyst growth in Pkd1(−/−) mice by regulating macrophage M2 polarization. Inflammation 46, 1272–1289 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Green G. M., Kass E. H., Factors influencing the clearance of bacteria by the lung. J. Clin. Invest. 43, 769–776 (1964). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Doran A. C., Yurdagul A., Tabas I., Efferocytosis in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 254–267 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McIlwain D. R., Berger T., Mak T. W., Caspase functions in cell death and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a008656 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pidwill G. R., Gibson J. F., Cole J., Renshaw S. A., Foster S. J., The role of macrophages in Staphylococcus aureus infection. Front. Immunol. 11, 620339 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thammavongsa V., Missiakas D. M., Schneewind O., Staphylococcus aureus degrades neutrophil extracellular traps to promote immune cell death. Science 342, 863–866 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alonzo F. III, Kozhaya L., Rawlings S. A., Reyes-Robles T., DuMont A. L., Myszka D. G., Landau N. R., Unutmaz D., Torres V. J., CCR5 is a receptor for Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxin ED. Nature 493, 51–55 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tam K., Lacey K. A., Devlin J. C., Coffre M., Sommerfield A., Chan R., O’Malley A., Koralov S. B., Loke P., Torres V. J., Targeting leukocidin-mediated immune evasion protects mice from Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J. Exp. Med. 217, e20190541 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andersson A. M., Larsson M., Stendahl O., Blomgran R., Efferocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils enhances control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in HIV-coinfected macrophages in a myeloperoxidase-dependent manner. J. Innate Immun. 12, 235–247 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parv K., Westerlund N., Merchant K., Komijani M., Lindsay R. S., Christoffersson G., Phagocytosis and efferocytosis by resident macrophages in the mouse pancreas. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 606175 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ural B. B., Yeung S. T., Damani-Yokota P., Devlin J. C., de Vries M., Vera-Licona P., Samji T., Sawai C. M., Jang G., Perez O. A., Pham Q., Maher L., Loke P., Dittmann M., Reizis B., Khanna K. M., Identification of a nerve-associated, lung-resident interstitial macrophage subset with distinct localization and immunoregulatory properties. Sci. Immunol. 5, eaax8756 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perez O. A., Yeung S. T., Vera-Licona P., Romagnoli P. A., Samji T., Ural B. B., Maher L., Tanaka M., Khanna K. M., CD169+ macrophages orchestrate innate immune responses by regulating bacterial localization in the spleen. Sci. Immunol. 2, eaah5520 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yeung S. T., Ovando L. J., Russo A. J., Rathinam V. A., Khanna K. M., CD169+ macrophage intrinsic IL-10 production regulates immune homeostasis during sepsis. Cell Rep. 42, 112171 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Diep B. A., Gill S. R., Chang R. F., Phan T. H. V., Chen J. H., Davidson M. G., Lin F., Lin J., Carleton H. A., Mongodin E. F., Sensabaugh G. F., Perdreau-Remington F., Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 367, 731–739 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Odds F. C., Brown A. J., Gow N. A., Candida albicans genome sequence: A platform for genomics in the absence of genetics. Genome Biol. 5, 230 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reyes-Robles T., Alonzo F. III, Kozhaya L., Lacy D. B., Unutmaz D., Torres V. J., Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxin ED targets the chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 to kill leukocytes and promote infection. Cell Host Microbe 14, 453–459 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S7