Introduction

The health of sexual and gender minority (SGM) individuals, an inclusive term for people whose sexual orientation or gender identity is not cisgender and heterosexual, is an area of increasing awareness in research. SGM populations face healthcare inequities that lead to worse outcomes in physical and mental health1. As of 2022, 7.1% of the adult population in the United States identifies as SGM. Twenty percent of Generation Z (born 1997-2012) adults identify as SGM. However, healthcare providers often have little knowledge of the healthcare needs of SGM patients2. In 2011, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine identified SGM health as an area of research need and priority3. This was followed by a National Academies report in 2022 recommending standardized language for collecting sexual orientation and gender identity data in research and clinical settings4.

Data on SGM people and gastroenterologic conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), are limited. Recent reviews on the care of transgender adolescents and young adults with IBD and on receptive anal intercourse in patients with perianal disease or ileoanal pouches have highlighted the lack of data and credible recommendations5, 6. These represent a few of the many areas where more data on the health of SGM people with IBD are needed and point to a critical gap in our knowledge that prevents data-driven and targeted measures to provide high-quality IBD care for SGM people.

This systematic review assesses the available research on the epidemiology and patient-reported health outcomes related to IBD in SGM individuals as a foundation for future researchers and clinicians.

Methods

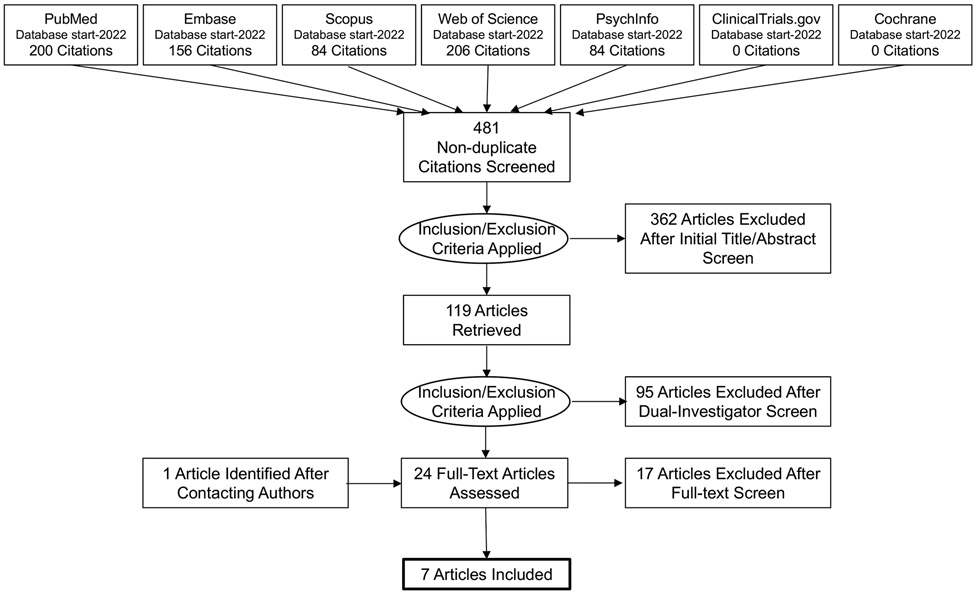

We conducted a search of PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, PsycInfo, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in March 2022 using keywords in the title or abstract and index terms. For the complete PubMed strategy, see Supplement. Duplicates were identified using EndNote and manual review.

Studies were eligible if they were published in English and included epidemiology or outcomes of IBD diagnosis or treatment in SGM individuals. SGM includes lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, Two-Spirit, queer, same-sex partnering, and intersex people (full list in Supplement). Case-studies, reviews, commentaries, and protocols without results were excluded.

Study characteristics and data are reported in Table 1. Study quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. The study and data were reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guideline.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies included in final synthesis (n=7).

| Reference | Publication Type |

Country | Study Design | SGM Populations |

IBD Types | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abramovich, 2020 | Peer-reviewed manuscript | Canada | Case-control study of transgender people identified using clinic records and general population controls | 2085 transgender individuals, sexual orientation not reported | Crohn's disease and colitis | 0.5% of transgender individuals had a diagnosis of Crohn's disease or colitis, compared with 0.6% of cisgender controls. P=0.56 |

| Dames, 2021 | Peer-reviewed manuscript | Online | Cross-sectional patient-delivered online survey of people who had undergone colorectal or pelvic floor surgery | 14% (n=87) of study respondents identified as LGBT+ | 31% of respondents CD and 34% of respondents had surgery for UC (not stratified within SGM group) | Qualitative data from LGBT+ participants regarding lack of discussion of gay sex, lack of support for gay people, concerns about proctectomy, inability to have receptive anal intercourse |

| Dibley 2014 | Peer-reviewed manuscript | United Kingdom | Mixed-methods study with survey and interviews of gay and lesbian people with IBD | Survey: 50 gay and lesbian people; Interviews: 14 gay men and 8 lesbians | Survey: CD = 26 (52%); UC = 16 (32%); other form of IBD = 8 (16%). Interviews: CD = 10 (45.5%); UC = 10 (45.5%), other form of IBD = 2 (9%). | Survey: Not reaching full potential was a higher priority for gay and lesbian population than reference general population. Interviews: Key themes included LGBT sexual activity, receiving healthcare, IBD and LGBT life, and identity and coming out |

| Fourie, 2022 | Thesis | United Kingdom | Qualitative study of people with IBD using phenomenological interviews | One gay man, one transman, two (one male, one female) bisexual | Not stratified within SGM group | Gay and bisexual people reported perianal disease interfered with sexual activity either through body image concerns or presence of a seton that caused interference. |

| Guardigni, 2018 | Conference abstract | Italy | Descriptive study of patients with IBD seen at an HIV clinic | 77% of cohort was MSM (n=13) | 100% of patients with IBD had UC (n=17); this was 0.7% of overall clinic population | HIV and ART-related factors not associated with likelihood of IBD flare in this predominantly MSM population |

| Logel, 2021 | Conference abstract | United States | Cross-sectional cohort of transgender and gender-diverse youth from 5 academic medical centers compared with general population prevalence rates from published literature | 32 (25%) were assigned male at birth and 96 (75%) were assigned female at birth. | CD and UC | Estimated rate of CD 18.4/10,000 transgender and gender-diverse persons and UC 7.6/10,000 transgender and gender-diverse persons, similar to the general population |

| Siwak, 2021 | Conference abstract | Poland | Descriptive study of patients with IBD seen at an HIV clinic | 98% of cohort was MSM (n=49) | CD in 7 patients (14%), UC in 41 patients (82%), and 2 (4%) IBD-U. | 20% of patients had IBD flare, all in people on ART |

Abbreviations: CD=Crohn’s disease; HIV=Human Immunodeficiency Virus; IBD=Inflammatory Bowel Disease; LGBT=Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender; MSM=Men who have sex with men; UC=Ulcerative Colitis

Results

Study selection

Our search yielded 481 non-duplicate citations (Figure 1), of which 24 underwent full text review. We contacted authors of two studies to inquire about additional data on SGM individuals, leading to the identification of one additional relevant publication. After full-text review, n=7 articles were included in the final synthesis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram for Study Inclusion.

Study characteristics

Most studies either assessed gender identity or sexual orientation. Two studies were on the incidence of IBD and other autoimmune diseases in transgender people. Two studies on IBD and HIV included majority men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM) populations. The most common study sites were the United States and the United Kingdom (Table 1).

Summary of studies

Although the number of studies was limited and had small sample sizes, three major categories emerged: the epidemiology of IBD in transgender people, sexual health concerns among SGM people with IBD, and IBD and HIV in MSM.

Epidemiology of IBD in transgender people

Transgender people are more likely to have chronic mental and physical illnesses than cisgender individuals7, which may be the result of sociodemographic and behavioral factors like poverty, discrimination, delayed care-seeking, and substance use. Abramovich, et al. retrospectively assessed the prevalence of chronic medical conditions, including IBD, in transgender adults in Ontario, Canada from clinics providing gender-affirming care using billing codes to ascertain outcomes8. Transgender people were significantly more likely to have asthma, COPD, diabetes, or HIV compared to general population controls, but Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis prevalence was the same in both groups (0.5% for transgender individuals, 0.6% for controls), though the IBD case count was small (n=71).

Logel, et al. retrospectively estimated autoimmune disease prevalence in individuals aged ≤26 years who sought gender-affirming care at five academic medical centers in the United States9. They used billing codes to identify autoimmune diseases and compared the prevalence to the general population prevalence reported in the literature. They identified higher prevalence of type 1 diabetes, lupus, and Graves’ disease in transgender youth, but the estimated prevalence of IBD did not significantly differ from the general population.

These studies suggest that the epidemiology of IBD may be similar in transgender and cisgender populations. No research has assessed IBD epidemiology in other SGM populations, the natural history of IBD in relation to gender-affirming medical and surgical treatment, or the rate of IBD-related complications in SGM people. Furthermore, there is significant potential for bias in both studies, since inclusion was based on identification of transgender individuals receiving care at a limited number of specialized centers, control groups may not have been exclusively cisgender individuals, and the studies relied on billing codes alone to ascertain outcomes.

Sexual health concerns among SGM people with IBD

Three studies included data on the sexual health concerns of SGM individuals with IBD. A major theme was the lack of credible relevant information on sexual health and function for SGM individuals with IBD. In the studies, this concern was predominantly voiced by gay men. They reported that “there is little/no information or support for gay people” who undergo colorectal or pelvic floor surgery10, and that there is a need for guidance on receptive anal intercourse after ileoanal pouch surgery11.

Sexual function after surgery or with perianal disease is a concern for SGM people. Multiple patients reported that surgery or a seton impeded sexual activity10-12. Others felt that IBD-related changes in the appearance their perianal area limited their sexual activity12. Some patients who had to alter their sexual activities described it as a source of sadness and frustration, though others adjusted to the changes without reporting significant stress11. There were also concerns about having a stoma or scars, which led some gay men to avoid relationships or feel uncomfortable participating in activities where they would be expected to be shirtless11.

Many sexual concerns of SGM individuals with IBD were shared with non-SGM people with IBD, including relationship challenges, feelings of inadequacy, body image issues, and embarrassing symptoms during sex12. In Dibley, et al., lesbian and gay people with IBD were more likely to be concerned about missing out on life experiences than a general IBD population comparison group; whether this was because of changes related to sex or intimacy was not explored11. Similarly, Fourie, et al. found that people whose IBD interfered with their sexual activities felt that it limited living a full life, a sentiment that non-SGM individuals also reported12.

IBD and HIV in MSM

Two abstracts evaluated IBD in MSM living with HIV using cross-sectional studies of HIV-clinic populations13, 14. Both study populations were predominantly MSM. The majority of individuals had UC (82% in Siwak, et al.14; 100% in Guardigni, et al.13). Guardigni, et al. reported that 0.7% of their HIV clinic population had IBD13. They found no HIV- or antiretroviral therapy (ART)-related factors associated with IBD flare, although the sample size was small (n=17). Siwak, et al. reported that 20% of their patients with IBD had a documented flare after HIV diagnosis and that all occurred in men on ART14.

Coming Out

One additional finding from our review was the role of “coming out” and self-disclosure for LGBTQ+ people with IBD. Dibley, et al. found that a major theme among gay and lesbian people with IBD was the use of similar strategies for coming out about sexual orientation and about having IBD11. Patients reported that openness about IBD was important for getting support and that openness about sexual orientation was important for preventing misconceptions and embarrassment.

Critical Appraisal

Most studies were small and lacked measurement of both sexual orientation and gender identity. They were descriptive and relied on either administrative data or self-report of SGM and IBD status and outcomes. No studies evaluated interventions. Most studies did not use validated measures of SGM identity. All three studies with quantitative outcomes comparing SGM and non-SGM groups had a significant risk of bias based on the Newcastle Ottawa scoring system. The highest quality studies identified were qualitative research. These utilized many best practices, such as use of trained interviewers, pilot testing, and clear sampling strategies.

Discussion

This review of seven articles on IBD epidemiology and patient-reported outcomes in SGM individuals identified key themes: IBD incidence and outcomes for transgender people, unaddressed sexual side effects of IBD in SGM populations, and issues of identity and self-disclosure. Important additional findings are that there are very few data on SGM individuals with IBD, and the studies that have examined this group are generally at high risk of bias and small, as seen for other health research in SGM populations.

Adult and pediatric studies found that transgender people have a similar prevalence of IBD to the general population8, 9. However, there are many important areas that remain unexplored. The first is whether gender-affirming care through medications, surgery, or both could affect IBD incidence or disease course. Data suggest that hormone levels may impact IBD symptoms and immunity in complex ways. Hormone therapy is associated with an increased risk of UC in postmenopausal women without IBD15, but in postmenopausal women with IBD, hormone therapy may protect against flares16. The gastrointestinal effects of hormone therapy for transgender men and women has not been rigorously assessed. Further, stress and trauma are associated with IBD incidence in the general population17. SGM individuals, especially transgender individuals, experience physical abuse, sexual violence, and intimate partner violence at much higher rates than the general population18. The interplay between SGM identity, stress and trauma and IBD outcomes is an important consideration for future study.

Another major theme in these studies was the lack of relevant information for SGM individuals with IBD about sex. Sexual practices like anal sex are not limited to SGM populations, but may be more common or have a more significant cultural role than in non-SGM populations. From a research perspective, existing validated survey instruments on sexual health and function often are not suitable for SGM populations because of implicit heterosexism19. There is a need for development and validation of new tools for sexual health research in SGM populations and tailored patient-focused education.

The third key theme was the similar skill-sets and coping techniques of SGM individuals with IBD. Internalized stigma is a common feature in both IBD and SGM populations and is associated with worse outcomes20, 21. Resilience can promote better health-related quality of life. As Dibley, et al. identified, the skills of coming out and identity formation for SGM people with IBD may overlap11. This role for resilience in coping with health challenges has also been observed in SGM individuals’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic22. Better understanding the skills SGM use to combat stigma and promote resilience may benefit all IBD patients.

Additional findings

We excluded case reports based on our pre-determined methodology, but several case reports highlighted important areas of consideration. One is the use of colonic or ileal tissue for neovagina construction. Garcia, et al. report a case series of 22 women who underwent vaginoplasty using the right colon including one woman who developed Crohn’s disease postoperatively that did not involve the neovagina.23. There were also case reports of IBD flares occurring in individuals with a colonic neovagina, one in which the neovagina was involved24 and another in which the neovagina was spared 25. These issues highlight the importance of additional research to evaluate the incidence, associated risks and management of IBD in people with neovaginas.

An additional consideration is was a that many existing studies of sex in IBD do not report sexual orientation or behaviors. Of the 54 mostly cross-sectional studies on sexuality in IBD included by our search terms, only eight included data on sexual orientation, and only three papers reported separate results for LGBTQ participants10, 12. The other papers did not include data on sexual orientation, with the implicit assumption that all participants were heterosexual.

Gaps in research

Population-based studies of IBD need to include sexual orientation and gender identity questions to allow for data collection around SGM status. This is critical in many areas of IBD research, as the effects of stigma, mistrust, and access to care for SGM people may broadly influence IBD outcomes and interact with other sociodemographic factors. High-quality data are lacking on the effects of gender-affirming care on IBD, sexual function in SGM people with IBD, outcomes following IBD-related surgeries, the effects of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and ART for HIV on IBD, and best practices for SGM care in GI. Given the high rates of mental health disorders and interpersonal and sexual violence suffered by SGM individuals18, there is a need for research on how to affect engagement in care and what practices should be implemented, especially around sensitive exams and procedures.

Limitations and Strengths

Despite searching multiple databases, we may have missed studies present in the gray literature or not in English. A strength of our review is the breadth of our investigation into existing literature on this topic. This is the first systematic review on IBD in SGM populations. In addition to assessing the findings and merits of existing research, we have identified research gaps and a need for improved study design.

Conclusions

This study summarizes the limited data available on SGM people with IBD and their experiences. Throughout the IBD literature, SGM data are poorly reported, including a lack of robust gender identity data collection and limited collection of sexual orientation and sexual behavior data. Future IBD research should collect data on SGM status, as recommended in the National Academies’ 2022 report. This includes identification of the necessary information for each study, be it gender identity, genetic information, hormone levels, anatomy, or social conditioning, and the use of validated measures to assess these. Furthermore, the diversity of SGM individuals includes intersectional identities across race, class, ability, and other factors, which are important to consider, as these may also alter the needs, outcomes, and experiences of people with IBD. SGM people have been understudied in luminal gastroenterology both in isolation and in intersectional contexts. Research in this area is important for the creation of interventions to improve the care experiences of SGM people with IBD and guide best practices.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive, and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under awards T32DK094775 (KLN) and F32DK134043 (KLN). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Availability:

Data and analytic methods available in manuscript and supplemental file.

References

- 1.Gonzales G, Przedworski J, Henning-Smith C. Comparison of Health and Health Risk Factors Between Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adults and Heterosexual Adults in the United States: Results From the National Health Interview Survey. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1344–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorsen C. An integrative review of nurse attitudes towards lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. Can J Nurs Res 2012;44:18–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian G, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Academies of Sciences E, and Medicine. Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation. In: Becker T, Chin M, Bates N, eds. Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schenker RB, Wilson E, Russell M, et al. Recommendations for Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Adolescents and Young Adults With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2021;72:752–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin T, Smukalla SM, Kane S, et al. Receptive Anal Intercourse in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Clinical Review. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:1285–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rich AJ, Scheim AI, Koehoorn M, et al. Non-HIV chronic disease burden among transgender populations globally: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Prev Med Rep 2020;20:101259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramovich A, De Oliveira C, Kiran T, et al. Assessment of Health Conditions and Health Service Use among Transgender Patients in Canada. JAMA Network Open 2020;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Logel S, Whitehead J, Maru J, et al. Transgender and gender-diverse youth have higher prevalence of certain autoimmune disease. Hormone Research in Paediatrics 2021;94:127. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dames NB, Squire SE, Devlin AB, et al. ‘Let’s talk about sex’: a patient-led survey on sexual function after colorectal and pelvic floor surgery. Colorectal Disease 2021;23:1524–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dibley L, Norton C, Schaub J, et al. Experiences of gay and lesbian patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A mixed methods study. Gastrointestinal Nursing 2014;12:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fourie S. An Interpretative Phenomenological Study Exploring the Intimacy and Sexuality Experiences of People Living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Volume Doctor of Philosophy. London, UK: King’s College London, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guardigni V, Scaioli E, Coladonato S, et al. Inflammatory bowel diseases: A hidden comorbidity in people living with HIV? Journal of the International AIDS Society 2018;21:153. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siwak E, Suchacz MM, Cielniak I, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in adult HIV-infected patients -a retrospective descriptive study from Warsaw, Poland. HIV Medicine 2021;22:171–172. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khalili H, Higuchi LM, Ananthakrishnan AN, et al. Hormone therapy increases risk of ulcerative colitis but not Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2012;143:1199–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kane SV, Reddy D. Hormonal replacement therapy after menopause is protective of disease activity in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:1193–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuller-Thomson E, West KJ, Sulman J, et al. Childhood Maltreatment Is Associated with Ulcerative Colitis but Not Crohn’s Disease: Findings from a Population-based Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:2640–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walters ML, Chen J, Breiding MJ. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amarasekera C, Wong V, Jackson K, et al. A Pilot Study Assessing Aspects of Sexual Function Predicted to Be Important After Treatment for Prostate Cancer in Gay Men: An Underserved Domain Highlighted. LGBT Health 2020;7:271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puckett JA, Levitt HM. Internalized Stigma Within Sexual and Gender Minorities: Change Strategies and Clinical Implications. Journal of Lgbt Issues in Counseling 2015;9:329–349. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taft TH, Keefer L, Leonhard C, et al. Impact of perceived stigma on inflammatory bowel disease patient outcomes. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:1224–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez KA, Abreu RL, Arora S, et al. “Previous Resilience Has Taught Me That I Can Survive Anything:” LGBTQ Resilience During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 2021;8:133–144. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia MM, Shen W, Zhu R, et al. Use of right colon vaginoplasty in gender affirming surgery: proposed advantages, review of technique, and outcomes. Surgical Endoscopy 2021;35:5643–5654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hennigan TW, Theodorou NA. Ulcerative colitis and bleeding from a colonic vaginoplasty. J R Soc Med 1992;85:418–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grasman ME, van der Sluis WB, de Boer NK. Neovaginal Sparing in a Transgender Woman With Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:e73–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data and analytic methods available in manuscript and supplemental file.