Summary

Molecular glues can induce proximity between a target protein and ubiquitin ligases to induce target degradation, but strategies for their discovery remain limited. We screened 3,200 bioactive small molecules and identified that C646 requires neddylation-dependent protein degradation to induce cytotoxicity. Although the histone acetyltransferase p300 is the canonical target of C646, we provide extensive evidence that C646 directly targets and degrades Exportin-1 (XPO1). Multiple cellular phenotypes induced by C646 were abrogated in cells expressing the known XPO1C528S drug-resistance allele. While XPO1 catalyzes nuclear-to-cytoplasmic transport of many cargo proteins, it also directly binds chromatin. We demonstrate that p300 and XPO1 co-occupy hundreds of chromatin loci. Degrading XPO1 using C646 or the known XPO1 modulator S109 diminishes the chromatin occupancy of both XPO1 and p300, enabling direct targeting of XPO1 to phenocopy p300 inhibition. This work highlights the utility of drug-resistant alleles and further validates XPO1 as a targetable regulator of chromatin state.

Keywords: Targeted protein degradation, phenotypic screening, target identification, p300, XPO1, chromatin, drug-resistance allele

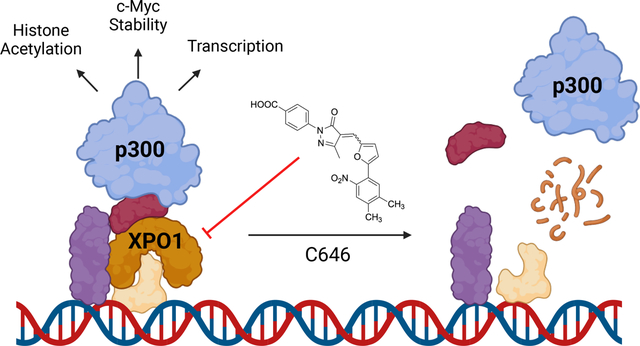

Graphical Abstract:

Chen et al. identify C646 as a small molecule degrader that requires neddylation-dependent protein degradation to exert its cytotoxicity from a high-throughput screen. C646 directly targets and degrades chromatin-bound XPO1, which abrogates p300 chromatin occupancy. Loss of XPO1 induces cellular phenotypes previously attributed to catalytic inhibition of p300.

Introduction

Targeted protein degradation by molecular glues is a promising therapeutic modality.1–3 To date, molecules that induce ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of proteins of interest have primarily been discovered by chance. While recent work has begun to define rational approaches to their development,4–6 additional screening approaches that expand the scope of degradable protein targets are needed.7 One recent approach profiled a small molecule library using cells in which genetic knockout of UBE2M impaired cullin ring ligase-mediated ubiquitination; molecules whose cytotoxicity was diminished in these neddylation-deficient cells were subsequently validated to degrade Cyclin K or RBM39.8 We sought to develop a similarly robust but simpler-to-implement phenotypic screening platform using chemical inhibition of the NEDD8-activating enzyme (NAE1)9 to facilitate rapid profiling across various cell lines.

This approach identified C646 as a small molecule whose cytotoxicity requires neddylation-dependent ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation. In silico screening first identified C646 as an inhibitor of the p300 histone acetyltransferase in vitro that also modulates cellular phenotypes relevant to p300, including lowering histone acetylation levels.10 More than a hundred subsequent publications have demonstrated that C646 impacts the epigenome11,12, in ways relevant to cancer, 13,14 neuroscience,15,16 and other diseases.17 While these studies support C646 as a useful small-molecule probe, no biophysical data supports a direct interaction between C646 and p300 in cells. Additionally, no studies have applied the gold-standard target validation approach of expressing a drug-resistance allele—typically, a mutant version of the target protein that resists modulation by the small molecule—to unambiguously demonstrate that C646’s cellular phenotypes stem from direct targeting of p300.18 Notably, C646 contains a thiol-reactive electrophilic chemical motif, and chemoproteomics studies noted that C646 interacts covalently with a significant number of cellular proteins.19 Together these observations suggest the potential for C646 to induce cellular phenotypes by mechanisms beyond direct inhibition of p300, particularly by covalent target engagement.

In this study, we demonstrate that in cells C646 directly engages and degrades Exportin-1 (XPO1).20 Critically, expression of the established XPO1 Cys528Ser (C528S) drug-resistance allele, which prevents covalent targeting of XPO1,21 substantially diminished the cytotoxicity and several other cellular effects of C646, supporting that direct targeting of XPO1 drives many of C646’s cellular phenotypes.10,12,13 While XPO1 has been extensively studied as a mediator of nuclear-to-cytoplasmic protein trafficking,20 it also occupies chromatin at sites of active transcription.22–26 We demonstrate that XPO1 and p300 extensively overlap in their chromatin occupancy genome-wide. Both C646 and the known XPO1 modulator S10927 globally diminish XPO1 and p300 chromatin occupancy, establishing an indirect mechanism for impaired p300 activity following direct targeting of XPO1. This work provides a simple-to-implement screening strategy for rapid identification of novel degraders, establishes XPO1 as responsible for many of C646’s cellular effects, and establishes XPO1 as a targetable chromatin factor regulating p300’s chromatin occupancy and histone acetylation.

Results

A past small-molecule screen identified novel cytotoxic molecular glues by assessing loss of cytotoxicity following genetic targeting of the E2 enzyme UBE2M, which is required for the ubiquitin ligase activity of cullin ring ligase complexes.8 We imagined that small-molecule inhibition of the upstream E1 enzyme NAE1 could also suppress ubiquitination and degradation of proteins targeted by novel cytotoxic degraders, provided that the cell line chosen was sufficiently resistant to NAE1 inhibition (Fig. 1A). Publicly available cancer cell line profiling data indicated that cell lines have wide-ranging sensitivity to the clinically-investigated NAE1 inhibitor pevonedistat,9 suggesting that various cell lines could potentially be utilized in such an assay (www.depmap.org). In the T-ALL cell line Jurkat, pretreatment with pevonedistat at 50 nM broadly suppressed the cytotoxicity of indisulam28 and CR86 after 72 hours, with the suppression of CR8 cytotoxicity being consistent with previous findings6, confirming that this ‘synthetic rescue’ screening system can identify multiple established molecular glues (Fig. 1B, Fig. S1A). Notably, pevonedistat killed Jurkat cells only at significantly higher concentrations (EC50 200 nM) (Fig. S1B).

Figure 1. A synthetic rescue screen identifies C646 as inducing cell death via a neddylation-dependent ubiquitin-mediated mechanism.

A) Schematic of the synthetic rescue screening strategy. Desired molecules show reduction of cytotoxicity when cullin ring ubiqutin ligase activity is impaired by inhibition of NAE1 with pevonedistat, indicative of a mechanism of cell death reliant on protein degradation. B) Cell viability (CellTiter-Glo) following treatment with CR8 alone or in combination with pevondedistat (50 nM) for 72 h in Jurkat cells (n=2 independent runs, each with at least 3 wells per concentration). C) Dot-plot representing the performance of each 3,200 bioactive small molecules in the synthetic rescue screen. X-axis, viability measured for each library molecule with only DMSO vehicle treatment; y-axis, change in viability when each library molecule was tested in combination with pevonedistat (50 nM). Hits (red box) were significantly cytotoxic as single agents (viability < 50%, x-axis) but showed at least 25% greater viability in combination with pevonedistat. Red circle, C646. Red asterisks denote electrophilic site for covalent addition on C646 and its loss on C37 (See also Table S1). D,E) Cell viability (CellTiter-Glo) following treatment with C646 alone or in combination with pevonedistat (50 nM) for 72 h in Jurkat cells (D, n=2 independent runs, each with at least 3 wells per concentration) and in MOLT-4 cells (E, n=2 independent runs, each with at least 3 wells per concentration).

With this 384-well comparative viability assay established, we next evaluated whether any molecules within a collection of 3,200 known bioactive small molecules would show enhanced viability in Jurkat cells when co-treated with pevonedistat. Jurkat cells were treated with each library member at 3 μM for 72 hours and cell viability was then assayed using CellTiter-Glo. As expected, in-plate positive control CR8 showed substantially enhanced viability on each of the 10 compound plates screened (Fig. S1C). Sixteen molecules were chosen for retest: these molecules were significantly cytotoxic at baseline (% viability < 50) and showed an increase of % viability of at least 25 in the presence of pevonedistat (Fig. 1C). Initial retest of these hits supported five active molecules: C646, Dabrafenib, Amprolium, Ciprofibrate, and Oxcarbazepine (Fig. S1D,E), but subsequent dose response confirmed only two molecules, C646 and dabrafenib, with C646, annotated as an inhibitor of the histone acyltransferase p300 (EP300),10 showing the largest gain of cell viability when co-treated with pevonedistat (Fig. 1D). C646 also showed a comparable level of pevonedistat-sensitive cell killing in a second cell line, MOLT4 (Fig. 1E, Fig. S1F), leading us to prioritize C646 for further study.

The initial report identifying C646 as a p300 inhibitor strongly suggested that C646 acts via a covalent mechanism-of-action, since close analog C37 lacking C646’s thiol-reactive olefin was inactive in cellular assays (Fig. 1C).10 While subsequent chemoproteomics studies have confirmed that C646 interacts covalently with more than 40 cellular proteins, no interaction with p300 has been reported.19 We next considered whether covalent targeting of proteins beyond p300 could potentially underlie C646’s cellular effects. Among the proteins established by chemoproteomics to be covalently labeled by C646, Exportin-1 (XPO1/CRM1) stood out as a particularly promising candidate since the XPO1-targeting small molecule S109 and its analogs (e.g., CBS9106) are established to cause cell death by inducing rapid and near-complete degradation of XPO1.27 Taken together, these data suggested that C646 might target and degrade XPO1 to exert is cellular effects.

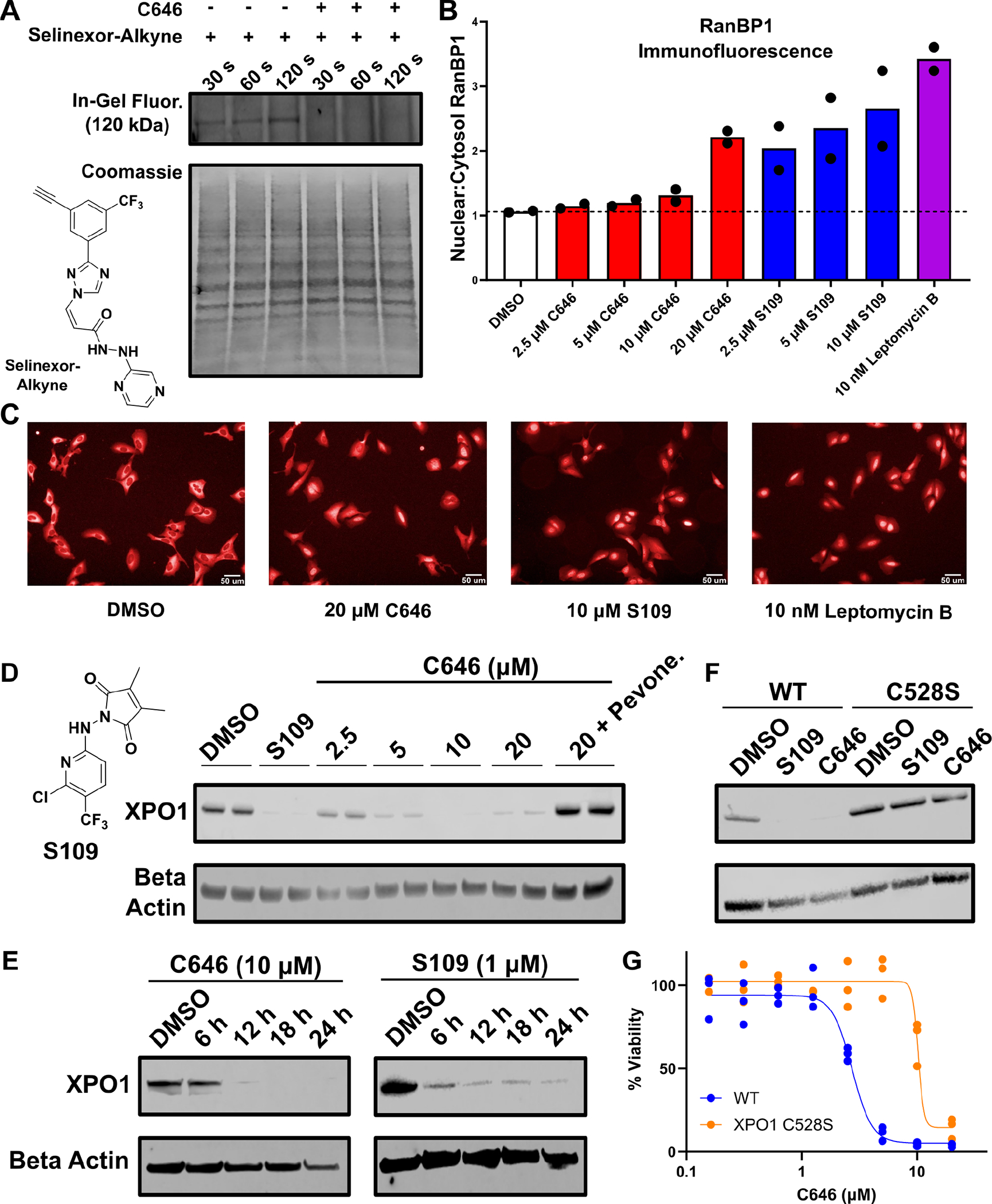

To evaluate this hypothesis, we first asked whether C646 was capable of targeting and degrading XPO1 in Jurkat cells. Indeed, C646 targeted XPO1 directly at Cys528, as C646 treatment fully blocked cellular labeling with an alkynyl derivative of Selinexor, the FDA-approved drug known to irreversibly target XPO1 at Cys528 (Fig. 2A)29. C646 also impaired the well-established XPO1 function of nuclear export, since the XPO1 cargo protein RANBP1 accumulated in the nucleus following C646 treatment (Fig. 2B,C). Additionally, cytotoxic concentrations of C646 and the established XPO1 modulator S109 both led to near-complete degradation of XPO1, with C646 achieving complete degradation within 12 hours and S109 achieving near-complete degradation in about 6 hours (Fig. 2D,E Fig. S2A). This loss of XPO1 was fully prevented by co-treatment with pevonedistat or in cells homozygously expressing the established XPO1 C528S resistance allele (Fig. 2D,F, Fig. S2A,B).21 This allele prevents covalent targeting of XPO1 and has been used extensively to establish that small molecule-induced effects on cell viability and other phenotypes derive from covalent targeting of XPO1 at Cys528.18,21 Following subcellular fractionation, both S109 and C646 also degraded XPO1 within the nuclear and chromatin compartments (Fig. S2C,D). Furthermore, proteomic analysis confirmed that both S109 and C646 depleted XPO1, with S109 inducing 95% depletion and C646 inducing 50% depletion in 8 hours (Fig. S2E,F, see also Table S2), consistent with the slower kinetics for XPO1 degradation by C646 noted on western blot. Together these studies establish that C646 directly targets XPO1 at Cys528, impairs its function, and induces its degradation.

Figure 2. C646 induces cell death by directly targeting and degrading XPO1.

A) In-gel fluorescence detection of proteins covalently labeled 30, 60, or 120 seconds after treatment with an alkynyl derivative of Selinexor (1 μM), which selectively labels XPO1 (120 kDa), with or without pre-treatment with C646 (10 μM). B,C) Nuclear-to-cytosol ratio of RanBP1 localization determined by immunofluorescence following small molecule treatment for 6h with representative images (n=2 independent runs, each with at least 4 wells per condition). D) Western blot for XPO1 following treatment for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of C646, S109 (2 μM), and pevonedistat (50 nM) in Jurkat cells. E) Western blot for XPO1 as in D in Jurkat cells at the indicated times after treatment with C646 or S109. F) Western blot for XPO1 as in D but using Jurkat cells edited using CRISPR/Cas9 to express the known XPO1 resistance allele C528S in homozygous form (C646, 10 μM; S109, 2 μM). Experiments in A, D, E, and F are representative of 2 independent experiments. G) Cell viability (CellTiter-Glo) following treatment with the indicated concentrations of C646 for 72h in Jurkat cells or Jurkat cells engineered to express the XPO1 C528S resistance allele (n=3 independent runs, each with at least 3 wells per concentration).

We next tested whether C646 induced cell death via XPO1. Critically, Jurkat cells expressing the established XPO1 C528S resistance allele gained significant resistance to C646-induced cell death, indicating that the cytotoxic effects of C646 observed below 10 μM are mediated by direct targeting of XPO1 (Fig. 2G). In analogy to C646, the cell killing of the established XPO1 degrader S109 was also diminished more than 10-fold either by pevonedistat co-treatment or expression of the XPO1 C528S drug resistance allele (Fig. S2G). These data establish that C646’s ability to directly target and degrade XPO1 is responsible for its cytotoxic effects at concentrations of 10 μM or below.

We proceeded to evaluate whether C646’s effects on chromatin and transcription, previously interpreted as stemming from modulation of p300, might stem from direct targeting of XPO1. We first confirmed previous reports that C646 treatment reduces global levels of H3K27Ac, a canonical chromatin mark deposited by p300 (Fig. 3A).10,13 Critically, Jurkat cells edited to express XPO1 C528S homozygously did not have reduced H3K27Ac levels after C646 treatment, demonstrating that loss of this chromatin mark represents a secondary consequence of targeting of XPO1 at C528 (Fig. 3A). Similar effects on H3K27Ac were also seen for the established XPO1 degrader S109 (Fig. 3A). Additionally, levels of the c-MYC transcription factor have also been shown to be diminished following C646 treatment.13 As with H3K27Ac, we confirmed that c-Myc levels were substantially reduced following C646 treatment in Jurkat cells (Fig. 3B). However, c-Myc levels were unchanged in cells edited to express XPO1 C528S homozygously, supporting that loss of c-Myc is a consequence of direct targeting of XPO1 (Fig. 3B). As with H3K27Ac, the known XPO1 degrader S109 also induced loss of c-Myc in WT Jurkat cells but not cells edited to express the XPO1 C528S resistance allele (Fig. 3B). Past work has also noted that p300 and C646 influence transcriptional activity of various genes, including immediate-early genes.12 In Jurkat cells, treatment with C646 or S109 led to 2- to 6-fold upregulation of a panel of four immediate-early genes: FOS, JUN, EGR1, and EGR2 (Fig. 3C). This transcriptional upregulation is consistent with previous observations that targeting XPO1 can lead to upregulation or downregulation of many transcripts26. Critically, transcript level changes following C646 or S109 treatment were suppressed in Jurkat cells expressing the XPO1 C528S resistance allele, highlighting that these C646-induced transcriptional changes also stem from covalent targeting of XPO1 (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Established cellular C646 phenotypes result from direct targeting of XPO1.

A) Western blot for acetylated histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27Ac) following treatment for 48h with C646 (5 μM, 10 μM), S109 (1 μM) in Jurkat cells either WT for XPO1 or edited via CRISPR/Cas9 to homozygously express XPO1 C528S (representative image from two independent experiments). B) Western blot for c-Myc following treatment for 24h with C646 (5 μM, 10 μM) or S109 (1 μM) in Jurkat cells either WT for XPO1 or edited via CRISPR/Cas9 to homozygously express XPO1 C528S (representative image from two independent experiments). C) RT-qPCR for the mRNA of FOS, JUN, EGR1, and EGR2 following treatment with the indicated concentration of C646 or S109 for 8h in Jurkat cells either WT for XPO1 or edited via CRISPR/Cas9 to homozygously express XPO1 C528S. Cells were co-treated with PMA/Ionomycin for 8h for the assessment of FOS and JUN expression (n=4 independent experiments with at least 4 wells per experiment). All measurements were normalized to GAPDH. False discovery rate was calculated using two-stage step-up method following multiple unpaired t-tests. D) Structures of C646, Selinexor, and CW8134. E) Western blot for XPO1 following the indicated treatments for 24h (representative of 2 independent experiments). F) Cell viability (CellTiter-Glo) following treatment with CW8134 for 72h in Jurkat cells (red), Jurkat cells co-treated with 50 nM pevonedistat (blue), and Jurkat cells homozygously expressing XPO1 C528S (black) (n=3 independent experiments with at least 3 wells per experiment).

We next sought a more potent C646 derivative that could retain C646’s XPO1 degrader property while demonstrating a wider range of concentrations over which its cellular effects are dependent on XPO1. We synthesized CW8134, which retains the scaffold of C646 but incorporates a bis-trifluoromethyl functionality from Selinexor (Fig. 3D). CW8134 at 0.5 μM induced near-total degradation of XPO1 (Fig. 3E). Additionally, CW8134-induced cytotoxicity is dependent on targeting of XPO1 Cys528 and is rescued by co-treatment with pevonedistat (Fig. 3F). These results spotlight CW8134 as a more potent and selective small molecule tool for the study of phenotypes associated with XPO1 degradation.

Since XPO1 and p300 have yet to be linked in the context of transcription and chromatin function, we sought to provide a rationale for how targeting XPO1 can induce cellular phenotypes previously linked to p300 modulation. While XPO1 is best studied for its role in mediating nuclear-to-cytoplasmic transport of protein cargoes, a growing body of work has established that XPO1 also directly localizes to chromatin, particularly at areas of active transcription.22–25 Since p300 also generally localizes to open chromatin regions, we next asked whether XPO1 may co-localize to chromatin with p300. In Jurkat cells that have not been activated, we previously found that XPO1 bound to thousands of sites on chromatin using CUT&RUN; in contrast, we detected minimal p300 chromatin occupancy (Fig. 4A, Fig. S3A). However, upon activation with PMA/Ionomycin, p300 was recruited to many sites where XPO1 was bound, including at IKZF1, JUN, EGR2, and globally across the genome (Fig. 4A, Fig. S3A). Remarkably, more than half of the identified p300 peaks co-localized with an XPO1 peak (Fig.4B, see Table S3 for high-confidence consensus peaks). Using a larger set of XPO1 peaks that were called in a previous study26, we found that more than 90% of p300 peaks co-localized with an XPO1 peak (Figure S3A). Gene ontology analysis of genes co-occupied by both p300 and XPO1 revealed significant enrichment for biological processes such as “T cell activation” and “chromatin organization,” suggesting p300 and XPO1 mark loci relevant for T cell function (Fig. 4C). Further, sites of XPO1 and p300 occupancy were similarly distributed among promoter and enhancer sites, with shared binding sites displaying a slight preference for promoter regions (Fig. S3B).

Figure 4. XPO1 and p300 co-localize to chromatin and are both sensitive to XPO1 modulation.

A) Genome browser view of XPO1 and p300 CUT&RUN profiles at the IKZF1 locus in Jurkat cells (representative tracks for XPO1, n=2; XPO1 and S109, n=1; XPO1 and C646, n=2; p300 [DMSO], n=2; p300 [PMA/Iono], n=2, p300 and S109, n=1; p300 and C646, n=2). B) Overlap of consensus XPO1 and p300 binding sites (upper diagram) and the overlap of genes assigned to those binding sites (lower diagram). See also Table S3. C) Gene ontology analysis of the most enriched biological processes for genes associated with shared peaks between XPO1 and p300. D) Global aggregate profiles and heat maps of XPO1 peaks in response to S109 and C646 treatment. E) Global aggregate profiles and heat maps of p300 peaks in response to S109 and C646 treatment. Where indicated, cells were co-treated with PMA/Ionomycin and S109 for 8h or PMA/Ionomycin and C646 for 24h.

Finally, we assessed how the chromatin occupancy of XPO1 and p300 changes following targeting of XPO1 with small molecules. Treatment with either S109 or C646 substantially diminished XPO1’s chromatin occupancy (Fig. 4A,D), in line with the near-total degradation of XPO1 observed for these molecules across multiple cellular compartments (Fig. 2D–F, Fig S2C–F). Critically, p300 binding was also abrogated by more than 50%, both at individual loci like IKZF1 and globally across the genome (Figure 4A,E, Fig. S3A). SP100030, which was recently characterized as a “Selective Inhibitor of Transcriptional Activation” that neither degrades XPO1 nor substantially inhibits nuclear export26, also abrogated p300 chromatin occupancy by more than 50% (Fig. S3C). Moreover, the chromatin occupancy loss induced by C646 for both XPO1 and p300 was abrogated in Jurkat cells expressing the XPO1 C528S allele in homozygous form (Fig. S3D), demonstrating that altered p300 chromatin occupancy is a consequence of direct targeting of XPO1. However, we did not detect a direct interaction between XPO1 and p300, suggesting that targeting XPO1 indirectly suppresses p300 chromatin occupancy (Fig. S3E,F). Taken together, our results support a model in which p300 chromatin binding is dependent on XPO1, such that XPO1 degradation by C646 or S109 indirectly diminishes p300 chromatin occupancy and H3K27 acetylation.

Discussion

Here we describe a simple-to-implement screening approach that identified C646 as a small molecule whose cytotoxicity depends on targeted protein degradation. Although C646 is annotated as an inhibitor of the p300 histone acetyltransferase, we demonstrate C646 and the known XPO1 degrader S109 directly target XPO1 and induce its degradation. It is currently unclear whether molecules like C646 and S109 represent bifunctional molecular glues that directly recruit cullin ring ligase complexes to XPO1 or whether these molecules may function as ‘destabilizers’ that alter the highly flexible conformation of XPO1 in ways that indirectly accelerate its ubiquitination and degradation.7 Importantly, degradation of XPO1 accounts for C646’s effects on cell viability, histone lysine acetylation, and transcript levels, since these phenotypes are all reversed by expression of the XPO1 Cys528Ser drug-resistant allele. Although a high concentration of C646 is likely to have targets beyond XPO1 that contribute to its cellular activity, our findings underscore drug resistance alleles as a powerful approach to link specific cellular targets to specific phenotypes. Given that more than 100 reports using C646 have been published, it is possible that other phenotypes reported for C646 may also be mediated by XPO1. Use of CRISPR/Cas9 to introduce XPO1 C528S mutations represents a straightforward method in any cell line of interest to distinguish phenotypes that result from direct targeting of XPO1 and those that arise from targeting other cellular proteins, including p300. Given the uncertainty regarding whether C646-induced cellular phenotypes stem from targeting p300, future studies seeking to inhibit p300 catalytic function might alternatively use recently-developed p300 active site inhibitors such as A485.30

Why does direct targeting of XPO1 induce cellular phenotypes, including diminished H3K27Ac levels, associated with p300 inhibition? We demonstrate that XPO1 and p300 extensively overlap in their chromatin occupancy genome-wide. As expected, targeted degradation of XPO1 using C646 or S109 induces loss of XPO1 from chromatin; unexpectedly, loss of XPO1 also induces loss of p300 from chromatin, supporting an indirect mechanism for impairing p300 function at chromatin. Beyond p300, XPO1 may interact with a broader spectrum of chromatin factors whose functions are sensitive to targeted XPO1 modulation. Although off-target effects may limit the use of C646 at high concentrations, degrader molecules such as C646, S109, and CW8134 represent powerful tools to evaluate how XPO1 modulation alters chromatin landscapes.

Limitations of the Study

The present work is largely conducted in the Jurkat leukemia cell line. One molecule with degrader activity was identified in this screen, but additional hits may be identified in other cell lines. Although the phenotypes induced by the screening hit C646 in Jurkat cells are the result of targeting XPO1, it is possible that these same phenotypes may be mediated through other cellular targets in other cell types. Broader use of the XPO1 C528S drug-resistance allele across a wider range of cell lines has the potential to clarify which phenotypes are XPO1-dependent. Furthermore, the mechanism by which C646 induces XPO1 degradation remains unclear. Although we established that degradation occurs in a neddylation-dependent manner, the specific E3 ubiquitin ligase that mediates this degradation is unknown. Additionally, it is unknown whether C646 functions as a molecular glue for XPO1 or induces destabilizing conformational changes on XPO1. Future studies that investigate these unknowns may expand the scope of small molecule degraders and glues.

Significance

This work highlights a simple-to-execute screening approach for identifying small molecules whose mechanism of cytotoxicity requires ubiquitin-mediated degradation of cellular proteins. We establish that C646’s ability to directly target and degrade Exportin-1 (XPO1), not its annotated p300 activity, accounts for its ability to kill cells, reduce histone acetylation, and impact transcription. Critically, the drug-resistance allele XPO1 C528S suppresses each of these diverse phenotypes, providing gold-standard evidence supporting XPO1 as C646’s functional target. Moreover, we establish that XPO1 and C646 extensively co-localize at chromatin and that small molecule degradation of XPO1 leads to loss of both XPO1 and p300 from chromatin. This result provides a mechanism by which direct targeting of XPO1 indirectly induces phenotypes expected of p300 inhibition. Additionally, our work reinforces XPO1 as a targetable chromatin factor that regulates the chromatin occupancy and function of a growing number of factors, including p300.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact:

Any further information and requests for materials, reagents, datasets, and protocols can be directed to the lead contact, Drew J. Adams (drew.adams@case.edu).

Materials availability:

Antibodies and reagents information are described in the STAR Methods section. For unique reagents and cell lines, any requests can be directed to and be fulfilled by the lead contact.

Data and code availability:

CUT&RUN sequencing datasets have been deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Proteomics datasets have been deposited at Proteomics Identification Database and are publicly available as of the date of publication. High-throughput screening data is provided as Table S1 in this paper. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental Model and Study Participant Details

Cell lines and reagents:

Cell lines were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 under humidified conditions. Jurkat E6–1 (TIB-152), MOLT-4 (CRL-1582), and U-2 OS (HTB-96) were all purchased from ATCC. All cell lines were maintained in glutamine-containing RPMI-1640 (Gibco, 11875093) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thomas Scientific, C788D86), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Corning, MT30002CI), and 10 mM HEPES (Gibco, 15630080).

Generating Jurkat XPO1 C528S cells and isolating clonal populations:

The XPO1 C528S mutation was introduced as previously described with modifications.21 The donor oligonucleotide for generating the XPO1 C528S mutation was synthesized by IDT with the following sequence (intended mutations in Iower case): 5’-GCTAAATAAGTATTATGTTGTTACAATAAATAATACAAATTTGTCTTATTTACAGGATCTATTAGGATTATcaGAACAGAAgcGcGGCAAAGATAATAAAGCTATTATTGCATCAAATATCATGTACATAGTAGG-3’. Guide RNA oligonucleotide targeting C528 was synthesized by Synthego with default modifications containing the following sequence: 5’-GGAUUAUGUGAACAGAAAAG-3’. Recombinant SpCas9–2NLS purchased from Synthego. The recombinant Cas9 was mixed with the guide and the donor template for 10 minutes at room temperature to allow for ribonucleoprotein complex formation (10 pmol Cas9 : 10 pmol sgRNA : 20 pmol donor template, per million cells). The mixture was then added to 10 million Jurkat cells and delivered using the Lonza 4D-Nucleofector system via the SE Cell Line 4D-Nucleofector Kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. After electroporation, the cells were allowed to proliferate for 72 hours prior to selection for resistant clones using 100 nM of Selinexor (Selleck Chemicals, S7252). After 14 days of selection, the surviving cells were cultured further. Once the surviving cells had grown sufficiently, they were plated in 384-well plates at a density of 0.5 cells per well to isolate single cell-derived colonies.

Generating Jurkat XPO1-TurboID or XPO1-miniTurbo cells and isolating clonal populations.

C-terminal fusion of TurboID-3X FLAG or miniTurbo-3X FLAG at the endogenous XPO1 locus in Jurkat cells was achieved using the CETCH-Seq protocol previously published by Savic et al31. pFETCh_Donor (EMM0021) was a gift from Eric Mendenhall & Richard M. Myers (Addgene plasmid #63934). The plasmid was first restriction digested BbsI (New England Biolabs, R3539S) and BsaI (New England Biolabs, R3733S) for 1h at 37°C. After purification with QIAGEN PCR Purification kit (QIAGEN, 28104), a Gibson assembly (New England Biolabs, E2611S) was used to assemble the digested plasmid backbone with gBlocks that bear homology to the C-terminus of the endogenous XPO1 locus and containing the coding sequence for TurboID or miniTurbo (see Data S2 for complete sequence of gBlocks)32. The assembled plasmid was co-transfected with SpCas9–2NLS (Synthego) into Jurkat cells via electroporation with the SE Cell Line 4D-Nucleofector X Kit (Lonza, V4XC-1024) using the Lonza 4D Nucleofector X Unit (AAF-1003X). The cells were allowed to rest for 3 days prior to selection with 750 μg/mL G418 (Gibco, 10131035).

METHOD DETAILS

Bioactive small molecule screening:

Jurkat cells were seeded in a sterile tissue culture 384-well plate (Corning, 3765) at 1000 cells and 50 ul of media per well using an EL406 Microplate Washer Dispenser (Biotek). Screening library molecules (a collection of 3,200 molecules derived from the Sigma LOPAC1280 and Selleck Bioactive Compound Library L1700 collections) were maintained as a 3 mM DMSO stock in Abgene storage 384-well plates (ThermoFisher Scientific; AB1055). Transfer of 50 nl of each library molecule to assay plates was achieved using a solid pin tool attached to a Janus automated workstation (PerkinElmer), resulting in a final screening concentration of 3 μM. DMSO was used as a negative control within each plate, while CR8 (Cayman Chemical, 14006) was used as a positive control at 200 nM. From each library plate, two replicate assay plates were generated that were identical except one plate was co-treated with Pevonedistat (added directly to cells and media before dispensing). Plates were then incubated at 37°C for 72 hours, at which time 5 μL of CellTiter-Glo reagent (Promega, G7572) was added to each well using the EL406 Microplate Washer Dispenser (Biotek). Plates were allowed to equilibrate for 10 minutes with shaking at room temperature before luminescence was immediately read using a Synergy Neo2Multimode microplate reader (Biotek). Viability was calculated relative to DMSO wells within each plate, and hits were called on the basis of at least 50% reduction in viability in the DMSO conditions as well as a % viability gain of at least 25% in the Pevonedistat condition.

Cell viability assay:

Jurkat cells were seeded in 384-well plates and treated with small molecule inhibitors as previously described. Following 72 hours of incubation, 5 μL of CellTiter-Glo (Promega, G7572) was dispensed into each well using the EL406 Microplate Washer Dispenser (Biotek). The mixture was allowed to equilibrate at room temperature with shaking for 10 minutes. Luminescence was calculated using the Synergy Neo2Multimode microplate reader (Biotek).

Small molecule.

Small molecules purchased in this study included C646 (MedChemExpress, HY-13823), Selinexor (Selleck Chemicals, S7252), Leptomycin B (Cayman Chemical, 10004976), CR8 (Cayman Chemical, 14006), Indisulam (Cayman Chemical, 22759), and Pevonedistat (Cayman Chemical, 15217). Selinexor-Alkyne was synthesized previously26 and CW8134 was synthesized as part of this paper, with purity and identity validated using 1H NMR and 13C NMR (see Data S1).

DNA extraction and Sanger sequencing:

Genomic DNA was collected using the QIAGEN DNEasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, 69504) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The target site containing the intended mutation in XPO1 was amplified using PCR with the following primers as described previously: fwd: 5’-TCTGCCTCTCCGTTGCTTTC, rev: 5’-CCAATCATGTACCCCACAGCT. After PCR amplification, Sanger sequencing was performed using the following primers: fwd: 5’-TGTGTTGGGCAATAGGCTCC, rev: 5’-GGCATTTTTGGGCTATTTTAATGAAA.

Western blot:

Jurkat cells were plated at a density of 500,000 cells in 1 mL of culture media and treated with respective drugs at concentrations and for times specified in the figure legends. After treatment, cells were washed once with PBS and resuspended in PBS containing Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 78440). Cells were lysed with the Fisher Scientific Sonic Dismembrator Model 60 using 15 × 1 second pulses at power level 3 and 4 °C. Protein concentrations were quantified using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 23225) and colorimetric development was measured using Biotek Synergy Neo2 microplate reader. After normalizing for protein input, reducing agent (Invitrogen, B009) and sample loading buffer (Invitrogen, B007) were added to each sample. Samples were resolved on 4%-12% gradient gels (Invitrogen, NW04122BOX). Protein gel transfer onto PVDF membrane was achieved with the iBlot2 Dry Transfer System (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and membranes were blocked with the Pierce Protein-Free T20 Blocking Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 37571). Primary antibodies used to probe membranes included the following: anti-XPO1 (Bethyl Laboratories, A300–469A), anti-H3K27Ac (abcam, ab4729), anti-c-Myc (Cell Signaling Technologies, 5605), ant-Beta Actin (Sigma-Aldrich, A3854). Following incubation with secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Cell Signaling Technologies, 7074), membranes were developed using either the SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 34580) or the SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 34095). Membranes were imaged using the LI-COR Odyssey Fc Imaging System.

In-gel fluorescence:

Jurkat cells were plated at a density of 500,000 cells in 1 mL of culture media. Cells were pre-treated with 10 μM C646 for 30 minutes prior to treatment with 1 μM Selinexor-Alkyne for 30 seconds to 120 seconds at 37 °C. After incubation, protein lysate concentration was measured as previously described. After normalizing for protein input for SDS-PAGE, the following was added to 20.75 μL of protein lysate to initiate click chemistry: (1) 1.5 μL of 20% SDS, (2) 0.5 μL of 5 mM Cy3.5-azide (Kerafast, FLP358), (3) 0.5 μL of 50 mM TCEP, (4) 1.25 μL of 1 mM TBTA, and (5) 0.5 μL of 50 mM CuSO4. After incubation at 25 °C for 1 hour, reducing agent (Invitrogen, B009) and sample loading buffer (Invitrogen, B007) were added to each sample. Samples were resolved on 4%-12% gradient gels (Invitrogen, NW04122BOX) and fluorescence was captured on the LI-COR Odyssey Fc Imaging System.

Immunofluorescence and analysis:

U-2 OS cells were plated at a density of 3,000 cells in 50 μL of media in a black, clear-bottom 96-well CellCarrier Ultra plate (Perkin Elmer, 50–209-9831) and allowed to attach overnight. Cells were then treated with respective inhibitors for 6h. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed and permeabilized, then stained with anti-RanBP1 (abcam, ab97659) and DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, D8417). Cells were imaged using the Operetta High Content Imaging and Analysis System (Perkin Elmer), with 7 fields captured per well at 20X magnification. Images were analyzed using the Harmony software on the Columbus data server (Perkin Elmer). Live cells were identified and their nuclear regions were established using DAPI staining. Selecting for these nuclei, the cytoplasmic region was defined according to the region of RanBP1 outside of the nuclear regions. The nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio of total signal intensity for RanBP1 was calculated.

Subcellular fractionation:

Jurkat cell pellets were collected as previously described, and nuclear and chromatin fractionation was achieved using the abcam nuclear extraction kit (ab113474) and chromatin extraction kit (ab117152), respectively, according to vendor’s protocol. In brief, for nuclear extraction, cell pellets were resuspended in pre-extraction buffer and centrifuged to isolate the nuclear pellet. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in extraction buffer and lysed with the Fisher Scientific Sonic Dismembrator Model 60 using 15 × 1 second pulses at power level 3 and 4°C. For chromatin extraction, cells are first resuspended in working lysis buffer and centrifuged to isolate the chromatin pellet. The chromatin pellet was then resuspended in the working extraction buffer and sonicated at 2 × 20 second pulses at power level 3 and 4°C. Following one more centrifugation, the supernatant was mixed 1:1 with the chromatin buffer before use.

RT-qPCR:

Jurkat cells were seeded in 12-well plates at 500,000 cells in 1 mL of culture and treated with respective small molecule inhibitors at concentrations specified in the figure for 8h. Cells were also co-treated with 50 nM PMA and 1 μM Ionomycin as specified in the figure legends. RNA was collected using the QIAGEN RNEasy Kit (QIAGEN, 74106), and RNA quality and quantity was assessed with a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer. cDNA synthesis was achieved using High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems, 4387406). The following Taqman exon-spanning primers were used for this work: GAPDH (Hs02786624_g1), FOS (Hs04194186_s1), JUN (Hs01103582_s1), EGR1 (Hs00152928_m1), EGR2 (Hs00166165_m1). Detection of relative transcript levels (normalized to GAPDH) by quantitative PCR was achieved using the QuantStudio 7 Flex System.

Proteomics sample preparation.

Jurkat cells were plated at 500,000 cells per 1 mL of culture media and treated with S109 (10 μM) or C646 (20 μM) for 8h. Cell lysates were collected as described previously. For each sample, 50 μg of cell lysate was first resuspended in 8M urea (Sigma-Aldrich, U1250), reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol (Sigma-Aldrich, 43816) for 30 minutes at room temperature, then alkylated with 25 mM iodoacetamide (Sigma-Aldrich, I6125) for 30 minutes at room temperature. After reduction and alkylation, the sample was diluted to less than 2M urea with 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich, S2454) prior to digestion with 1 μg of Lys-C (Promega, V1671) overnight at 37°C. After digestion, the samples are desalted on BioPure SPN Mini TARGA C18 columns (The Nest Group, HUM S18R) that have been pre-washed with methanol (Sigma-Aldrich, 439193) and 0.1% formic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, 5.43804). After washing the columns twice with 0.1% formic acid, samples were eluted using 0.1% acetic acid in 80% acetonitrile (Sigma-Aldrich, 34851) then dried using the DNA120 SpeedVac (Thermo Fisher Scientific, DNA120–115). The dried samples were then resuspended in 30 μL of 0.1% formic acid.

Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry.

Samples were analyzed on the timsTOF Pro 2 Q-Tof mass spectrometry system operating in positive ion mode, coupled with a CaptiveSpray ion source (both from Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen). The HPLC column was a Bruker 15 cm × 75 μm id C18 ReproSil AQ, 1.9 μm, 120 Å reversed-phase capillary chromatography column. One μL volumes of the extract were injected and the peptides eluted from the column by an acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid gradient at a flow rate of 0.3 μL/min were introduced into the source of the mass spectrometer on-line. The digests were analyzed using a Parallel Accumulation–Serial Fragmentation DDA method was used to select precursor ions for fragmentation with a TIMS-MS scan followed by 10 PASEF MS/MS scans. The TIMS-MS survey scan was acquired between 0.60 and 1.6 Vs/cm2 and 100–1,700 m/z with a ramp time of 166 ms. The total cycle time for the PASEF scans was 1.2 seconds and the MS/MS experiments were performed with collision energies between 20 eV (0.6 Vs.cm2) to 59 eV (1.6 Vs/cm2). Precursors with 2–5 charges were selected with the target value set to 20,000 a.u and intensity threshold to 2,500 a.u. Precursors were dynamically excluded for 0.4 s. The results were searched and quantified with PEAKS Online 11 (Patch build 1.9.2023–10-10_100742) software using the human Swiss-Prot database (2023_01 release) with mass correction, chimera association, 20 ppm error tolerance for precursors, 0.05 DA error tolerance for fragments, oxidation and N-terminal acetylation for variable modifications, and carbamidomethylation for fixed modifications. See Table S2 for all proteins quantified in this paper.

Synthesis of CW8134

To a solution of Compound 1 (1 g, 5.71 mmol) and Compound 1A (1.55 g, 6.00 mmol) in THF (30 mL), Pd (PPh3)4 (330.20 mg, 285.75 μmol) and Na2CO3 (2 M, 14.29 mL) were added. The mixture was stirred at 70°C for 12h under N2. LC-MS showed Compound 1 was consumed and 59% of desired compound was detected. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure to remove solvent. The residue was purified by flash silica gel chromatography (ISCO®; 20 g SepaFlash® Silica Flash Column, Eluent of 0~1% Ethyl acetate/Petroleum ether gradient @ 100 mL/min) (SiO2, Petroleum ether: Ethyl acetate=5:1, Rf (P1) =0.42) to afford Compound 2 (1.3 g, 4.22 mmol, 73.81% yield) as a yellow solid. MS-ESI (m/z) calculated for C13H6F6O2 [M−H]−: 307.0; Found 307.3.

To a solution of Compound 2 (200 mg, 648.98 μmol) and Compound 2B (141.61 mg, 648.98 μmol) in DMSO (3.0 mL) AcOH (77.94 mg, 1.30 mmol, 74.30 μL) was added and the mixture was stirred at 55°C for 2 hrs. LC-MS showed Compound 2 was consumed and 60% of desired compound was detected. The reaction mixture was filtered and the filtrate was purified by Prep-HPLC (column: Phenomenex luna C18 100*40mm*3 μm; mobile phase: [H2O (0.1% TFA)-ACN]; gradient: 60%-90% B over 8.0 min). The purity of final compound was not high enough after first purification, so it was further purified by Prep-HPLC (column: Phenomenex luna C18 100*40mm*3 um; mobile phase: [H2O (0.1% TFA)-ACN]; gradient: 65%-95% B over 8.0 min) to afford CW8134 (4.72 mg, 9.19 μmol, 1.42% yield, 98.98% purity) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6 400MHz) δ ppm 12.85 (br d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 8.62 (s, 3H), 8.18 (s, 1H), 8.12 – 8.06 (m, 2H), 8.04 – 7.98 (m, 2H), 7.92 – 7.87 (m, 2H), 2.37 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (DMSO Bruker_002_400MHz) δ ppm 167.2, 162.1, 156.0, 152.0, 151.3, 142.0, 131.8, 131.5, 131.2, 130.7, 130.0, 127.3, 126.4, 125.6, 124.9, 122.4, 117.2, 114.3, 13.3. See Data S1 for 1H NMR and 13C NMR.

CUT&RUN sample preparation:

CUT&RUN samples were prepared using the CUTANA ChIC/CUT&RUN Kit (Epicypher 14–1048) according to manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, 500,000 Jurkat cells were activated with 50 nM PMA and 1 μM Ionomycin and co-treated with either 1 μM S109 for 8h or 10 μM C646 for 24h, followed by fixation in culture media supplemented with 1% formaldehyde for 1 minute prior to quenching with 125 mM glycine. Cells were then permeabilized, bound to concanavalin A magnetic beads, and incubated overnight with 0.5 μg of anti-XPO1 (Bethyl Laboratories, A300–469A) or anti-p300 (Cell Signaling Technologies, 54062) antibodies at 4°C. Non-targeting IgG control (Epicypher, 13–0042) was used as a negative control for each experiment. Following overnight incubation, excess antibodies were removed and protein A/G MNase was added to the antibody-bound beads to cleave target-bound genomic DNA at 4°C for 2 hours. After quenching the cleavage reaction, the samples were de-crosslinked and proteolytically digested overnight. CUT&RUN DNA was isolated with column chromatography, and libraries were prepared using NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England BioLabs). Libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 with paired-end 150 bp reads at a read depth of 10 million paired-end reads per sample.

Peak calling and analysis:

Raw reads were quality checked and adaptor trimmed using Trim Galore! Version 0.6.7 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/). Trimmed reads were then aligned to the hg38 genome build using bowtie2 version 2.5.0.33 Duplicate reads were filtered using Picard MarkDuplicates version 2.18.2.4 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). RPGC-normalized bigwig and bedgraph files were generated using the bamcoverage function in deeptools version 3.5.2.34 Peaks were called using SEACR version 1.3 under stringent conditions and normalized to the respective IgG control.35 The XPO1 and p300 consensus peaks were defined to be the set of peaks that were present in both of two independent biological replicates. Peak-gene assignments, gene ontology analysis, and peak location distribution for peaks was analyzed using GREAT.36 The intersect function in bedtools version 2.30.0 was used to determine the overlap of peaks between XPO1 and p300.37 Venn diagrams and overlaps are visualized using the eulerr package in R or using the following webtool: (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/). Global aggregate plots and heat maps were generated using the computeMatrix and plotHeatmap functions in deeptools, where RPGC-normalized bigwig files were used for the score files and the consensus peaks for XPO1 and p300 were used as the region files.

Biotin identification.

Jurkat cells expressing XPO1-miniTurbo or XPO1-TurboID are first grown in biotin-depleted RPMI-1640 (MyBioSource, MBS653376) supplemented with dialyzed FBS (Cytiva, SH30079.03HI), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Corning, MT30002CI), and 10 mM HEPES (Gibco, 15630080) for 4 days. Afterwards, the media was replaced and the cells were co-treated with 50 nM PMA, 1 μM Ionomycin, and 50 μM biotin (Cayman Chemical, 22582). After incubation, cell lysates were collected and protein concentrations measured as previously described. Cell lysate inputs were first desalted using Zeba Spin Desalting Columns with 7K MWCO (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 89883) before incubation with 25 μL of Pierce Streptavidin Magnetic Beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 88817) overnight at 4°C while rotating. After incubation, the beads were separated from the supernatant using a magnet, the beads washed twice using PBS, and proteins eluted using sample loading buffer and reducing agent as described in Western blot at 95°C. Proteins of interest were detected as described above using anti-XPO1 (Bethyl Laboratories, A300–469A) and anti-p300 (Cell Signaling Technologies, 54062).

Co-immunoprecipitation.

Jurkat cell lysates were collected and protein concentrations measured as previously described. After normalizing for input, each sample was incubated with the anti-p300 (Cell Signaling Technologies, 54062) at 1:50 dilution for 2h at 4°C while rotating. After incubation, 50 μL of Protein A Magnetic Beads (Cell Signaling Technologies, 73778) overnight at 4°C while rotating. After incubation, the beads were processed as described in biotin identification for gel electrophoresis and western blot.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

GraphPad Prism was used for all graphical data analysis. False discovery rate was calculated using two-stage step-up method following multiple unpaired t-tests as specified in the corresponding figure legends. All data are expressed without error bars to display the complete spread of all independent replicate experiments. Additional details regarding number of independent experiments are found in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Document S1. Figures S1–S3, Data S1, and Data S2.

Table S2. Proteomics quantification for S109 and C646, related to STAR Methods and Figure S2.

Key resources table.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| XPO1 | Bethyl Laboratories | Cat# A300-469A |

| H3K27Ac | abcam | Cat# ab4729 |

| RanBP1 | abcam | Cat# ab97659 |

| p300 | Cell Signaling Technologies | Cat# 54062 |

| c-Myc | Cell Signaling Technologies | Cat# 5605 |

| Anti-Rabbit IgG, HRP-linked | Cell Signaling Technologies | Cat# 7074 |

| Beta Actin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A3854 |

| Non-targeting IgG | Epicypher | Cat# 13-0042 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Biological samples | ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| LOPAC 1280 Small Molecule Library | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# LO1280 |

| Bioactive Compound Library | Selleck Chemicals | Cat# L1700 |

| RPMI-1640 | Gibco | Cat# 11875093 |

| Biotin-depleted RPMI-1640 | MyBioSource | Cat# MBS653376 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | Thomas Scientific | Cat# C788D86 |

| Dialyzed Fetal Bovine Serum | Cytiva | Cat# SH30079.03HI |

| Penicillin/Streptomycin | Corning | Cat# MT30002CI |

| HEPES | Gibco | Cat# 15630080 |

| DMSO | VWR | Cat# WN182 |

| CR8 | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 14006 |

| Indisulam | Cayman Chemcal | Cat# 22759 |

| Leptomycin B | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 10004976 |

| Pevonedistat (MLN4924) | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 15217 |

| Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 10008014 |

| Ionomycin | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 10004974 |

| Biotin | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 22852 |

| C646 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-13823 |

| Selinexor-Alkyne (See Data S1) | Chen et al.26 | N/A |

| CW8134 (See Data S1) | This paper | N/A |

| Selinexor (KPT-330) | Selleck Chemicals | Cat# S7252 |

| SpCas9-2NLS | Synthego | N/A |

| SE Cell Line 4D-Nucleofector X Kit | Lonza | Cat# V4XC-1024 |

| PBS | VWR | Cat# 45000-446 |

| Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (100X) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 78440 |

| Reducing Agent (10X) | Invitrogen | Cat# B009 |

| Sample Loading Buffer (4X) | Invitrogen | Cat# B007 |

| 20X Bolt MES SDS Running Buffer | Invitrogen | Cat# B002 |

| 4–12% gradient polyacrylamide gels | Invitrogen | Cat# NW04122BOX |

| Streptavidin Alexa Fluor 680 Conjugate | Invitrogen | Cat# S32358 |

| Pierce Protein-Free T20 Blocking Buffer | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 37571 |

| SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 34580 |

| SuperSignal West Femto PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 34095 |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 436143 |

| TCEP | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# C4706 |

| TBTA | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 678937 |

| Copper (II) Sulfate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 451657 |

| DAPI | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D8417 |

| Glycine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 50046 |

| Formaldehyde | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 252549 |

| Triton X-100 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 93443 |

| Cy3.5-azide | Kerafast | Cat# FLP358 |

| rLys-C, Mass Spec Grade | Promega | Cat# V1671 |

| Urea | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# U1250 |

| Dithiothreitol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 43816 |

| Iodoacetamide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# I6125 |

| Ammonium Bicarbonate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# S2454 |

| Methanol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 439193 |

| Formic Acid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 5.43804 |

| Acetonitrile | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 34851 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Qiagen DNEasy Blood & Tissue Kit | Qiagen | Cat# 69504 |

| Qiagen RNEasy Kit | Qiagen | Cat# 74106 |

| Qiagen PCR Purification Kit | Qiagen | Cat# 28104 |

| Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 23225 |

| Pierce Streptavidin Magnetic Beads | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 88817 |

| CellTiter-Glo | Promega | Cat# G7572 |

| High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit | Applied Biosystems | Cat# 4387406 |

| Taqman Gene Expression Master Mix | Applied Biosystems | Cat# 4369016 |

| Taqman Gene Expression Assay: GAPDH | Applied Biosystems | Cat# Hs02786624_g1 |

| Taqman Gene Expression Assay: FOS | Applied Biosystems | Cat# Hs04194186_s1 |

| Taqman Gene Expression Assay: JUN | Applied Biosystems | Cat# Hs01103582_s1 |

| Taqman Gene Expression Assay: EGR1 | Applied Biosystems | Cat# Hs00152928_m1 |

| Taqman Gene Expression Assay: EGR2 | Applied Biosystems | Cat# Hs00166165_m1 |

| CUTANA ChIC/CUT&RUN Kit | Epicypher | Cat# 14-1048 |

| NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit | New England Biolabs | Cat# E7645S |

| Nuclear Extraction Kit | abcam | Cat# ab113474 |

| Chromatin Extraction Kit | abcam | Cat# ab117152 |

| SpCas9-2NLS | Synthego | N/A |

| BbsI-HF | New England Biolabs | Cat# R3539S |

| BsaI-HF | New England Biolabs | Cat# R3733S |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | New England Biolabs | Cat# E2611S |

| G418 | Gibco | Cat# 10131035 |

| Protein A Magnetic Beads | Cell Signaling Technologies | Cat# 73778 |

| Deposited data | ||

| CUT&RUN-Seq datasets | This paper | Gene Expression Omnibus: GSE244396 |

| Proteomics datasets | This paper | Proteomics Identification Database: PXD050274 |

| High-throughput screening data (See Table S1) | This paper | N/A |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Jurkat E6-1 | ATCC | Cat# TIB-152 |

| Jurkat E6-1 XPO1C528S/C528S | Chen et al.26 | N/A |

| MOLT-4 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1582 |

| U 2-OS | ATCC | Cat# HTB-96 |

| Jurkat E6-1 XPO1-TurboID-3X-FLAG | This paper | N/A |

| Jurkat E6-1 XPO1-miniTurbo-3X-FLAG | This paper | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Donor template for C528S introduction (intended mutation in lower case): GCTAAATAAGTATTATGTTGTTACAATAAATAATACAAATTTGTCTTATTTACAGGATCTATTAGGATTATcaGAACAGAAgcGcGGCAAAGATAATAAAGCTATTATTGCATCAAATATCATGTACATAGTAGG |

Neggers et al.21 (IDT) | N/A |

| Guide RNA targeting XPO1 Cys528: GGAUUAUGUGAACAGAAAAG |

Neggers et al.21 (Synthego) | N/A |

| Guide RNA Targeting XPO1 C-terminus: UCUCUGCAACUCGUUAGCAG |

Chen et al.26 (Synthego) | N/A |

| PCR Primer: XPO1 C528S Forward TCTGCCTCTCCGTTGCTTTC |

Neggers et al.21 (IDT) | N/A |

| PCR Primer: XPO1 C528S Reverse: CCAATCATGTACCCCACAGCT |

Neggers et al.21 (IDT) | N/A |

| Sequencing Primer: XPO1 C528S Forward: TGTGTTGGGCAATAGGCTCC |

Neggers et al.21 (IDT) | N/A |

| Sequencing Primer: XPO1 C528S Reverse: GGCATTTTTGGGCTATTTTAATGAAA |

Neggers et al.21 (IDT) | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pFETCh_Donor plasmid | Addgene | Cat# 63934 |

| gBlock sequences for generating endogenous XPO1-miniTurbo-3X FLAG and XPO1-TurboI D-3X-FLAG fusions in Jurkat cells via CRISPR-Cas9 (See Data S2) | This paper(IDT) | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Graphpad Prism | Graphpad Software | RRID: SCR_002798 |

| Columbus Image Data Storage and Analysis System | Perkin Elmer | https://www.perkinelmer.com/Product/columbus |

| Trim Galore! Version 0.6.7 | Krueger, 2015 | https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/; RRID: SCR_011847 |

| Bowtie2 Version 2.5.0 | Langmead and Salzberg33 | https://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml; RRID: SCR_016368 |

| Picard MarkDuplicates Version 2.18.2.4 | http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/ | N/A |

| deepTools Version 3.5.2 | Ramirez et al.34 | https://deeptools.readthedocs.io/en/develop/; RRID: SCR_016366 |

| SEACR Version 1.3 | Meers et al.35 | https://seacr.fredhutch.org/ |

| GREAT Version 4.0.4 | McLean et al.36 | https://great.stanford.edu/great/public/html/ |

| bedtools Version 2.30.0 | Quinlan and Hall37 | https://bedtools.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html#; RRID: SCR_006646 |

| Microsoft Excel 2016 | Microsoft | N/A |

| Inkscape Version 1.3.2 | Inkscape | RRID: SCR_014479 |

| PEAKS Online 11 Patch build 1.9.2023-10-10_100742 | Bruker | N/A |

| Other | ||

| 384-well assay plates | Corning | Cat# 3765 |

| 384-well storage plates | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# AB1055 |

| 96-well CellCarrier Ultra plates | Perkin Elmer | Cat# 50-209-9831 |

| BioPureSPN Mini, FastEq, TARGA C18 | The Nest Group | Cat# HUM S18R |

| Zeba Spin Desalting Columns 7K MWCO | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 89883 |

| EL406 Microplate Washer Dispenser | Biotek | N/A |

| Synergy Neo2Multimode Microplate Reader | Biotek | N/A |

| Janus Automated Workstation | Perkin Elmer | N/A |

| Lonza 4D-Nucleofector X Unit | Lonza | Cat# AAF-1003X |

| Sonic Dismembrator Model 60 | Fisher Scientific | N/A |

| iBlot2 Dry Transfer System | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# IB24002 |

| LI-COR Odyssey Fc Imaging System | LI-COR | N/A |

| Operetta High Content Imaging and Analysis System | Perkin Elmer | N/A |

| QuantStudio 7 Flex Real-Time PCR System | Applied Biosystems | Cat# 4485701 |

| DNA120 SpeedVac | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# DNA120-115 |

| timsTOF Pro 2 | Bruker | N/A |

Highlights.

Small molecule degraders are identified by selecting for neddylation-dependent cytotoxicity

C646 directly targets XPO1 at Cys528 to induce XPO1 degradation

Degradation of XPO1 phenocopies inhibition of p300 histone acetyltransferase

p300 chromatin occupancy and function are dependent on chromatin-bound XPO1

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI171104 (D.J.A.), the Falk Medical Research Trust (D.J.A), the Harrington Discovery Institute (Y.F.C.), and support from the CWRU School of Medicine and Thomas F. Peterson, Jr. Y.F.C. and J.L.S. were supported by the CWRU Medical Scientist Training Program (NIH T32GM007250). Y.F.C. was also supported by NIH T32GM135081, and M.J.A.P. was also supported by NIH F31NS122176. Additional support was provided by the Small-Molecule Drug Development and Genomics Shared Resources of the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30 CA043703), the Genomics Shared Resource of the University of Colorado Cancer Center (P30 CA046934), and the Proteomics Shared Resource of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation (The timsTOF Pro2 instrument was purchased via an NIH shared instrument grant, S10 OD030398). Figure 1a and graphical abstract were created with BioRender.com. We thank Y. Fedorov and M. Scemama for technical assistance and discussion. We also thank Y. Li, X. Liu, Z. Yang, and R. Ding from WuXi Apptec for discussion and support around chemical synthesis. We additionally acknowledge M. Miyagi, L. Li, and B. Willard for proteomics support.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

Y.F.C. and D.J.A. are inventors on a provisional patent (63/627,975) filed by Case Western Reserve University on the synthesis of small molecules that target XPO1. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dewey JA, Delalande C, Azizi S-A, Lu V, Antonopoulos D, and Babnigg G (2023). Molecular Glue Discovery: Current and Future Approaches. J. Med. Chem. 66, 9278–9296. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasso JM, Tenchov R, Wang D, Johnson LS, Wang X, and Zhou QA (2023). Molecular Glues: The Adhesive Connecting Targeted Protein Degradation to the Clinic. Biochemistry 62, 601–623. 10.1021/acs.biochem.2c00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oleinikovas V, Gainza P, Ryckmans T, Fasching B, and Thomä NH (2024). From Thalidomide to Rational Molecular Glue Design for Targeted Protein Degradation. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 64, 291–312. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-022123-104147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong G, Ding Y, He S, and Sheng C (2021). Molecular Glues for Targeted Protein Degradation: From Serendipity to Rational Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 64, 10606–10620. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toriki ES, Papatzimas JW, Nishikawa K, Dovala D, Frank AO, Hesse MJ, Dankova D, Song J-G, Bruce-Smythe M, Struble H, et al. (2023). Rational Chemical Design of Molecular Glue Degraders. ACS Cent. Sci. 9, 915–926. 10.1021/acscentsci.2c01317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Słabicki M, Kozicka Z, Petzold G, Li Y-D, Manojkumar M, Bunker RD, Donovan KA, Sievers QL, Koeppel J, Suchyta D, et al. (2020). The CDK inhibitor CR8 acts as a molecular glue degrader that depletes cyclin K. Nature 585, 293–297. 10.1038/s41586-020-2374-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domostegui A, Nieto-Barrado L, Perez-Lopez C, and Mayor-Ruiz C (2022). Chasing molecular glue degraders: screening approaches. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 5498–5517. 10.1039/D2CS00197G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayor-Ruiz C, Bauer S, Brand M, Kozicka Z, Siklos M, Imrichova H, Kaltheuner IH, Hahn E, Seiler K, Koren A, et al. (2020). Rational discovery of molecular glue degraders via scalable chemical profiling. Nat Chem Biol 16, 1199–1207. 10.1038/s41589-020-0594-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nawrocki ST, Griffin P, Kelly KR, and Carew JS (2012). MLN4924: a novel first-in-class inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme for cancer therapy. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 21, 1563–1573. 10.1517/13543784.2012.707192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowers EM, Yan G, Mukherjee C, Orry A, Wang L, Holbert MA, Crump NT, Hazzalin CA, Liszczak G, Yuan H, et al. (2010). Virtual Ligand Screening of the p300/CBP Histone Acetyltransferase: Identification of a Selective Small Molecule Inhibitor. Chemistry & Biology 17, 471–482. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henry RA, Kuo Y-M, Bhattacharjee V, Yen TJ, and Andrews AJ (2015). Changing the Selectivity of p300 by Acetyl-CoA Modulation of Histone Acetylation. ACS Chem. Biol. 10, 146–156. 10.1021/cb500726b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crump NT, Hazzalin CA, Bowers EM, Alani RM, Cole PA, and Mahadevan LC (2011). Dynamic acetylation of all lysine-4 trimethylated histone H3 is evolutionarily conserved and mediated by p300/CBP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7814–7819. 10.1073/pnas.1100099108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogiwara H, Sasaki M, Mitachi T, Oike T, Higuchi S, Tominaga Y, and Kohno T (2016). Targeting p300 Addiction in CBP -Deficient Cancers Causes Synthetic Lethality by Apoptotic Cell Death due to Abrogation of MYC Expression. Cancer Discovery 6, 430–445. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ono H, Kato T, Murase Y, Nakamura Y, Ishikawa Y, Watanabe S, Akahoshi K, Ogura T, Ogawa K, Ban D, et al. (2021). C646 inhibits G2/M cell cycle-related proteins and potentiates anti-tumor effects in pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep 11, 10078. 10.1038/s41598-021-89530-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marek R, Coelho CM, Sullivan RKP, Baker-Andresen D, Li X, Ratnu V, Dudley KJ, Meyers D, Mukherjee C, Cole PA, et al. (2011). Paradoxical Enhancement of Fear Extinction Memory and Synaptic Plasticity by Inhibition of the Histone Acetyltransferase p300. J. Neurosci. 31, 7486–7491. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0133-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maddox SA, Watts CS, and Schafe GE (2013). p300/CBP histone acetyltransferase activity is required for newly acquired and reactivated fear memories in the lateral amygdala. Learn. Mem. 20, 109–119. 10.1101/lm.029157.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu F, Romantseva T, Park Y-J, Golding H, and Zaitseva M (2020). Production of fever mediator PGE2 in human monocytes activated with MDP adjuvant is controlled by signaling from MAPK and p300 HAT: Key role of T cell derived factor. Molecular Immunology 128, 139–149. 10.1016/j.molimm.2020.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freedy AM, and Liau BB (2021). Discovering new biology with drug-resistance alleles. Nat Chem Biol 17, 1219–1229. 10.1038/s41589-021-00865-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shrimp JH, Sorum AW, Garlick JM, Guasch L, Nicklaus MC, and Meier JL (2016). Characterizing the Covalent Targets of a Small Molecule Inhibitor of the Lysine Acetyltransferase P300. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 7, 151–155. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen KT, Holloway MP, and Altura RA (2012). The CRM1 nuclear export protein in normal development and disease. Int J Biochem Mol Biol 3, 137–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neggers JE, Vanstreels E, Baloglu E, Shacham S, Landesman Y, and Daelemans D (2016). Heterozygous mutation of cysteine528 in XPO1 is sufficient for resistance to selective inhibitors of nuclear export. Oncotarget 7, 68842–68850. 10.18632/oncotarget.11995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conway AE, Haldeman JM, Wechsler DS, and Lavau CP (2015). A critical role for CRM1 in regulating HOXA gene transcription in CALM-AF10 leukemias. Leukemia 29, 423–432. 10.1038/leu.2014.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oka M, Mura S, Otani M, Miyamoto Y, Nogami J, Maehara K, Harada A, Tachibana T, Yoneda Y, and Ohkawa Y (2019). Chromatin-bound CRM1 recruits SET-Nup214 and NPM1c onto HOX clusters causing aberrant HOX expression in leukemia cells. eLife 8, e46667. 10.7554/eLife.46667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oka M, Mura S, Yamada K, Sangel P, Hirata S, Maehara K, Kawakami K, Tachibana T, Ohkawa Y, Kimura H, et al. (2016). Chromatin-prebound Crm1 recruits Nup98-HoxA9 fusion to induce aberrant expression of Hox cluster genes. eLife 5, e09540. 10.7554/eLife.09540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oka M, Otani M, Miyamoto Y, Oshima R, Adachi J, Tomonaga T, Asally M, Nagaoka Y, Tanaka K, Toyoda A, et al. (2023). Phase-separated nuclear bodies of nucleoporin fusions promote condensation of MLL1/CRM1 and rearrangement of 3D genome structure. Cell Reports 42, 112884. 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YF, Ghazala M, Friedrich RM, Cordova BA, Petroze FN, Srinivasan R, Allan KC, Yan DF, Sax JL, Carr K, et al. (2024). Targeting the chromatin binding of exportin-1 disrupts NFAT and T cell activation. Nat Chem Biol, 1–12. 10.1038/s41589-024-01586-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niu M, Chong Y, Han Y, and Liu X (2015). Novel reversible selective inhibitor of nuclear export shows that CRM1 is a target in colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Biology & Therapy 16, 1110–1118. 10.1080/15384047.2015.1047569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han T, Goralski M, Gaskill N, Capota E, Kim J, Ting TC, Xie Y, Williams NS, and Nijhawan D (2017). Anticancer sulfonamides target splicing by inducing RBM39 degradation via recruitment to DCAF15. Science 356, eaal3755. 10.1126/science.aal3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferreira BI, Cautain B, Grenho I, and Link W (2020). Small Molecule Inhibitors of CRM1. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 625. 10.3389/fphar.2020.00625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lasko LM, Jakob CG, Edalji RP, Qiu W, Montgomery D, Digiammarino EL, Hansen TM, Risi RM, Frey R, Manaves V, et al. (2017). Discovery of a selective catalytic p300/CBP inhibitor that targets lineage-specific tumours. Nature 550, 128–132. 10.1038/nature24028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savic D, Partridge EC, Newberry KM, Smith SB, Meadows SK, Roberts BS, Mackiewicz M, Mendenhall EM, and Myers RM (2015). CETCh-seq: CRISPR epitope tagging ChIP-seq of DNA-binding proteins. Genome Res. 25, 1581–1589. 10.1101/gr.193540.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Branon TC, Bosch JA, Sanchez AD, Udeshi ND, Svinkina T, Carr SA, Feldman JL, Perrimon N, and Ting AY (2018). Efficient proximity labeling in living cells and organisms with TurboID. Nat Biotechnol 36, 880–887. 10.1038/nbt.4201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langmead B, and Salzberg SL (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9, 357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramírez F, Ryan DP, Grüning B, Bhardwaj V, Kilpert F, Richter AS, Heyne S, Dündar F, and Manke T (2016). deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Research 44, W160–W165. 10.1093/nar/gkw257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meers MP, Tenenbaum D, and Henikoff S (2019). Peak calling by Sparse Enrichment Analysis for CUT&RUN chromatin profiling. Epigenetics & Chromatin 12, 42. 10.1186/s13072-019-0287-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLean CY, Bristor D, Hiller M, Clarke SL, Schaar BT, Lowe CB, Wenger AM, and Bejerano G (2010). GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat Biotechnol 28, 495–501. 10.1038/nbt.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinlan AR, and Hall IM (2010). BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Document S1. Figures S1–S3, Data S1, and Data S2.

Table S2. Proteomics quantification for S109 and C646, related to STAR Methods and Figure S2.

Data Availability Statement

CUT&RUN sequencing datasets have been deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Proteomics datasets have been deposited at Proteomics Identification Database and are publicly available as of the date of publication. High-throughput screening data is provided as Table S1 in this paper. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.