Over the past decades, inequities in stroke have gained increasing attention. Social determinants of health (SDOH) - conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life – are known drivers of inequities. Yet, little is known about the impact of SDOH on stroke incidence, care, and outcomes. Understanding these relationships will be helpful in designing interventions to address inequities. The purpose of this review is to summarize manuscripts published from 2022 through 2023 on the impact of SDOH on stroke.

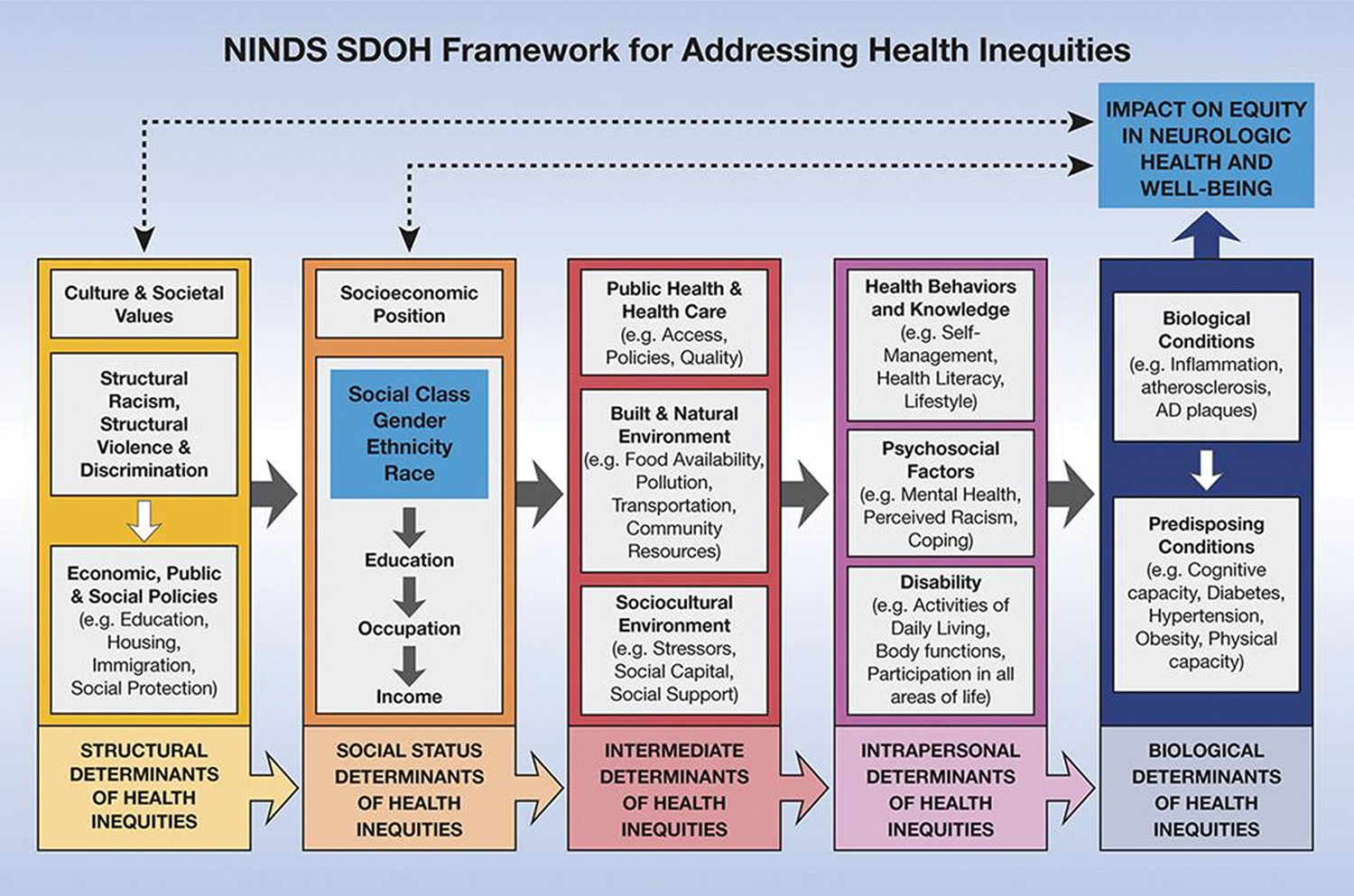

Three commissioned manuscripts focused on SDOH and neurological disease. The American Heart Association Scientific Statement “Strategies to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Inequities in Stroke Preparedness, Care, Recovery, and Risk Factor Control” summarized intervention studies addressing racial and ethnic inequities in stroke care and outcomes1. The SDOH subgroup of the National Advisory Neurological Disorders and Stroke Council Working Group for Health Disparities and Inequities in Neurological Disorders published an article delineating key considerations for SDOH in neurological disease, outlining recent interventions, knowledge gaps, and recommendations to address SDOH2. Finally, the article “Determinants of Inequities in Neurologic Disease, Health, and Well-being: The NINDS Social Determinants of Health Framework” illustrated a model for conceptualizing the impact of SDOH on inequities in neurological disease (Figure 1)3. This model, adapted from three sources - the World Health Organization Commission on SDOH4, the Schulz et al. model5, and the work of Williams et al.6 - shows the interplay between upstream structural determinants (cultural and social values; structural racism; economic, public and social policies); social status determinants (socioeconomic position, class, education, occupation, and income): intermediate factors (public health and healthcare, built environment, sociocultural environment); intrapersonal determinants (health behaviors and knowledge, psychosocial factors, disability); biological determinants, and inequities in neurological health.

Figure 1.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke SDOH Framework for Addressing Health Disparities. Reproduced from Griffith DM, et. al, Neurology, 20233 (reprinted with permission).

With regards to structural determinants of health (Figure 1), several recent studies focused on the impact of immigration on stroke risk and care. Studies utilizing administrative data in Canada found that stroke incidence followed a J-shaped curve between the proportion life spent in Canada and stroke incidence and disability; it was highest among immigrants who had either immigrated at an early age or immigrated recently7, and that the attributable cost of stroke among immigrants was significantly higher than among non-immigrants8. Registry data in Denmark suggested that immigrants had greater pre-hospital delays compared to their non-immigrant counterparts9. Furthermore, immigrants were less likely to receive acute reperfusion therapies even when adjusting for time to presentation, and had lower odds of stroke unit admission, dysphagia screening, and early rehabilitation services than non-immigrants10. An analysis of administrative data in the United States (US) showed that compared with US-born Black individuals, all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates were lower among Black individuals born in Africa, the Caribbean, South America, and Central America, but stroke-specific mortality rates were similar11.

Neighborhood, zip code, and other related location-specific measures (largely shaped by discriminatory policies) are increasingly recognized as important structural determinants of health. Living in a low-income neighborhood was found to be an important determinant of hypertension severity in intracerebral hemorrhage survivors and partially explained the excess likelihood of uncontrolled blood pressures among Black vs. White people in a primary prevention setting12,13. The area deprivation index, a validated measure of community-level socioeconomic deprivation, was associated with greater stroke severity, infarct volume, and 30-day mortality after stroke14,15. A related study demonstrated that socially disadvantaged US counties had significantly higher stroke mortality than counties with low area-level social deprivation16. Similarly, historical redlining was associated with modern-day stroke prevalence in New York City independently of contemporary individual measures of socioeconomic status17. Data from the Black Women’s Health Study suggested that Black women who experienced interpersonal racism had higher stroke incidence than those without prior experiences of racism18, thus establishing a direct link between interpersonal racism and stroke incidence later in life.

Social status determinants of health (Figure 1) were shown to have an impact on stroke prevalence and care. Low education, low income, and living in a health care professionals shortage area were associated with increased community-level stroke prevalence in a cross-sectional study of residents in New York City17 and were critical drivers of the excess likelihood of uncontrolled blood pressure among Black vs. White participants in the REGARDS study13. Unemployed and low-income stroke patients had lower likelihood of receiving reperfusion therapies, even when only considering patients with timely hospital arrival19. When using composite measures of SES, incorporating information on education, income, and occupation, low SES was associated with worse long-term recovery of upper limb motor function20, increased death and functional dependency at 3 months21, and greater decline in health-related quality of life up to 10 years after stroke22. An analysis from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey demonstrated that the prevalence of food insecurity among stroke survivors was higher than among those without prior history of stroke, and low education and income were associated with higher likelihood of facing food insecurity after stroke23.

In the past two years, although our understanding of the impact of SDOH on stroke has expanded, numerous gaps remain. First, it is critical to understand how each SDOH individually and in combination affects stroke prevalence, care, and outcomes. Second, more research is needed to determine which individual-level, place-level, or policy interventions are efficacious in addressing stroke inequities2. Prior research in other areas suggest that community engaged, multi-level, interdisciplinary interventions are likely to address inequities1. Additionally, addressing more structural and social status determinants will likely have a larger impact than interventions geared towards individual health literacy and behavior change1,3. Once efficacious interventions are identified, it will be necessary to evaluate effectiveness, implementation, and dissemination.

Supplementary Material

Disclosures

Dr. Faigle has nothing to disclose. Dr. Towfighi reports grants from the American Heart Association; grants from the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities; and grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- SDOH

Social determinants of health

- US

United States

References

- 1.Towfighi A, Boden-Albala B, Cruz-Flores S, El Husseini N, Odonkor CA, Ovbiagele B, Sacco RL, Skolarus LE, Thrift AG, American Heart Association Stroke C, et al. Strategies to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Inequities in Stroke Preparedness, Care, Recovery, and Risk Factor Control: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2023;54:e371–e388. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Towfighi A, Berger RP, Corley AMS, Glymour MM, Manly JJ, Skolarus LE. Recommendations on Social Determinants of Health in Neurologic Disease. Neurology. 2023;101:S17–S26. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000207562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffith DM, Towfighi A, Manson SM, Littlejohn EL, Skolarus LE. Determinants of Inequities in Neurologic Disease, Health, and Well-being: The NINDS Social Determinants of Health Framework. Neurology. 2023;101:S75–S81. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000207566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization CoSDoH. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Commission on Social Determinants of Health final report. In. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulz AJ, Williams DR, Israel BA, Lempert LB. Racial and spatial relations as fundamental determinants of health in Detroit. Milbank Q. 2002;80:677–707, iv. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:105–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vyas MV, Fang J, Austin PC, Kapral MK. Proportion of life spent in Canada and stroke incidence and outcomes in immigrants. Ann Epidemiol. 2022;74:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2022.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vyas MV, Fang J, de Oliveira C, Austin PC, Yu AYX, Kapral MK. Attributable Costs of Stroke in Ontario, Canada and Their Variation by Stroke Type and Social Determinants of Health. Stroke. 2023;54:2824–2831. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.123.043369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mkoma GF, Johnsen SP, Agyemang C, Hedegaard JN, Iversen HK, Andersen G, Norredam M. Processes of Care and Associated Factors in Patients With Stroke by Immigration Status. Med Care. 2023;61:120–129. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mkoma GF, Norredam M, Iversen HK, Andersen G, Johnsen SP. Use of reperfusion therapy and time delay in patients with ischaemic stroke by immigration status: A register-based cohort study in Denmark. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29:1952–1962. doi: 10.1111/ene.15303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Looti AL, Ovbiagele B, Markovic D, Towfighi A. All-Cause, Cardiovascular, and Stroke Mortality Among Foreign-Born Versus US-Born Individuals of African Ancestry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12:e026331. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.026331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abramson JR, Castello JP, Keins S, Kourkoulis C, Rodriguez-Torres A, Myserlis EP, Alabsi H, Warren AD, Henry JQA, Gurol ME, et al. Biological and Social Determinants of Hypertension Severity Before vs After Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Neurology. 2022;98:e1349–e1360. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akinyelure OP, Jaeger BC, Oparil S, Carson AP, Safford MM, Howard G, Muntner P, Hardy ST. Social Determinants of Health and Uncontrolled Blood Pressure in a National Cohort of Black and White US Adults: the REGARDS Study. Hypertension. 2023;80:1403–1413. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.20219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghoneem A, Osborne MT, Abohashem S, Naddaf N, Patrich T, Dar T, Abdelbaky A, Al-Quthami A, Wasfy JH, Armstrong KA, et al. Association of Socioeconomic Status and Infarct Volume With Functional Outcome in Patients With Ischemic Stroke. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e229178. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.9178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lusk JB, Hoffman MN, Clark AG, Bae J, Luedke MW, Hammill BG. Association Between Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status and 30-Day Mortality and Readmission for Patients With Common Neurologic Conditions. Neurology. 2023;100:e1776–e1786. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000207094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Havenon A, Zhou LW, Johnston KC, Dangayach NS, Ney J, Yaghi S, Sharma R, Abbasi M, Delic A, Majersik JJ, et al. Twenty-Year Disparity Trends in United States Stroke Death Rate by Age, Race/Ethnicity, Geography, and Socioeconomic Status. Neurology. 2023;101:e464–e474. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000207446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jadow BM, Hu L, Zou J, Labovitz D, Ibeh C, Ovbiagele B, Esenwa C. Historical Redlining, Social Determinants of Health, and Stroke Prevalence in Communities in New York City. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e235875. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.5875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheehy S, Aparicio HJ, Palmer JR, Cozier Y, Lioutas VA, Shulman JG, Rosenberg L. Perceived Interpersonal Racism and Incident Stroke Among US Black Women. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2343203. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.43203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buus SMO, Schmitz ML, Cordsen P, Johnsen SP, Andersen G, Simonsen CZ. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Reperfusion Therapy for Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2022;53:2307–2316. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.037687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolf S, Holm SE, Ingwersen T, Bartling C, Bender G, Birke G, Meyer A, Nolte A, Ottes K, Pade O, et al. Pre-stroke socioeconomic status predicts upper limb motor recovery after inpatient neurorehabilitation. Ann Med. 2022;54:1265–1276. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2059557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindmark A, Eriksson M, Darehed D. Mediation Analyses of the Mechanisms by Which Socioeconomic Status, Comorbidity, Stroke Severity, and Acute Care Influence Stroke Outcome. Neurology. 2023;101:e2345–e2354. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000207939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun YA, Phan H, Buscot MJ, Thrift AG, Gall S. Area-level and individual-level socio-economic differences in health-related quality of life trajectories: Results from a 10-year longitudinal stroke study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2023;32:107188. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2023.107188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim-Tenser MA, Ovbiagele B, Markovic D, Towfighi A. Prevalence and Predictors of Food Insecurity Among Stroke Survivors in the United States. Stroke. 2022;53:3369–3374. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.038574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.