Abstract

Although the worldwide incidence of tuberculosis has been slowly decreasing, the global disease burden remains substantial (~9 million cases and ~1·5 million deaths in 2013), and tuberculosis incidence and drug resistance are rising in some parts of the world such as Africa. The modest gains achieved thus far are threatened by high prevalence of HIV, persisting global poverty, and emergence of highly drug-resistant forms of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis is also a major problem in health-care workers in both low-burden and high-burden settings. Although the ideal preventive agent, an effective vaccine, is still some time away, several new diagnostic technologies have emerged, and two new tuberculosis drugs have been licensed after almost 50 years of no tuberculosis drugs being registered. Efforts towards an effective vaccine have been thwarted by poor understanding of what constitutes protective immunity. Although new interventions and investment in control programmes will enable control, eradication will only be possible through substantial reductions in poverty and overcrowding, political will and stability, and containing co-drivers of tuberculosis, such as HIV, smoking, and diabetes.

Introduction

Tuberculosis is a communicable infectious disease, transmitted almost exclusively by cough aerosol, caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, and characterised pathologically by necrotising granulomatous inflammation usually in the lung (~85% of cases), although almost any extrapulmonary site can be involved. Tuberculosis probably emerged about 70 000 years ago, accompanied by migration of modern human beings out of Africa;1 it remains a global plague, and untreated, has a mortality of ~70% in smear-positive people.2 Tuberculosis has killed roughly 1 billion people in the past two centuries,3 still ranks amongst the top ten causes of death worldwide, results in substantial chronic lung disability, and reduces gross domestic product (GDP) substantially in endemic countries. Audio and video links in the appendix provide insight into living conditions and challenges facing patients with tuberculosis in an endemic country.

Epidemiology of tuberculosis

The precipitous decline in burden of tuberculosis in the UK occurred before interventions such as tuberculosis chemotherapy became available, highlighting the importance of socioeconomic factors (overcrowding, poor nutrition, etc) in the genesis of tuberculosis (appendix).4

Although global tuberculosis incidence has slowly declined during the past 13 years (rate of ~1·5% per year),5 disease burden remains remarkably substantial. In 2013, an estimated 9 million incident cases of tuberculosis (equivalent to 126 cases per 100 000 population) were reported,5 with more than 60% of the burden concen- trated in the 22 high-burden countries (map of global epidemiology shown in the appendix). However, the case detection rate was only around 64%, and worryingly, around 3·3 million people with tuberculosis were missed (undiagnosed or not reported). By contrast, tuberculosis mortality has declined substantially in the past 20 years from almost 30 per 100 000 to around 16 per 100 000 people in 2013.5

In 2013, 1·1 million people were estimated to have tuberculosis–HIV co-infection (13% of the global incident caseload). About 80% of these cases occurred in Africa (map of global disease burden shown in the appendix), and HIV-associated tuberculosis deaths accounted for about 25% of the total number of tuberculosis-related deaths.5 In 2013, 480 000 new cases of multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis were estimated to have occurred worldwide, resulting in about 210 000 deaths. MDR tuberculosis was reported in about 3·5% of new cases and 20·5% of re-treated cases (appendix).5 Several worrying trends exist with drug-resistant tuberculosis (appendix), including widespread emergence of exten- sively drug-resistant (XDR) tuberculosis6 and resistance beyond XDR tuberculosis.7 In 2013, 550 000 incident cases of tuberculosis in children and 80 000 deaths in children with HIV were reported.5 Children are a vulnerable and often neglected subgroup; further aspects of management of tuberculosis in children are reviewed elsewhere.8,9

Key risk factors associated with tuberculosis (and the magnitude of risk; table 1)10,11 include poverty and overcrowding, undernutrition, alcohol misuse, HIV, silicosis, chronic renal failure needing dialysis, fibro-apical radiographic changes, diabetes, tobacco smoking, and immune-suppressive therapy. However, attributable risk, which varies according to global burden of the associated risk factor, has been estimated as follows: HIV (11%), smoking (15·8%), diabetes (7·5%), alcohol abuse (9·8%), undernutrition (26·9%), and indoor air pollution (22·2%).12 These data have obvious implications for public health interventions and highlight the need for integration of health services for communicable and non-communicable diseases. Modelling studies, notwithstanding their limitations, suggest that tuberculosis elimination is probably only achievable by 2050 if therapeutic and diagnostic interventions (early case detection and high cure rates) are combined with preventive strategies (vaccines and treatment of the latent tuberculosis reservoir in 2 billion people in high-burden and low-burden settings).13 The WHO-endorsed End TB Strategy outlines global strategy and targets for tuberculosis prevention, care, and control after 2015 (appendix).

Pathogenesis of tuberculosis

Transmission

Tuberculosis transmission occurs when the organism is aerosolised by the cough of an infected patient and inhaled into the alveoli of a new host. In some cases, transmission is highest within family units, but outbreaks in almost any setting are common, from schools to factories to public transportation. Two studies14,15 in low-incidence settings used molecular methods involving repetitive genetic elements to show that a large fraction of cases, even in low-incidence settings, were the result of recent transmission rather than reactivation of latent disease. Such techniques have shaped how we think about tuberculosis transmission,16 but are now giving way to whole- genome sequencing (WGS), which provides a higher degree of confidence in strain identities compared with conventional methods.17 WGS has reopened the question of reactivation versus recent transmission in low-incidence settings and has been used to establish that M tuberculosis clades are geographically restricted and co-evolved with modern human beings.1 This geographical restriction of clades seems to be breaking down with the widespread emergence of clades that evolved in Asia (now often referred to as the Beijing lineage).

Large gaps exist in our knowledge about how best to reduce transmission, apart from the obvious need to improve case finding, since many cases of tuberculosis are undiagnosed. Work using carbon dioxide concentrations in air as a proxy for rebreathing have suggested one practical method to measure transmission risk in different settings,18 and re-emphasised the crucial role of ventilation in reducing risk. Epidemiological data suggest that some strains might transmit more easily than others, but the molecular mechanisms under- pinning these observations are unclear. Host factors might have a role in transmission, but patients with HIV do not seem to be either more or less capable of transmitting tuberculosis.19

Outcomes after infection

Exposure to M tuberculosis infrequently leads to symptomatic disease. Thus, although the statistic that one-third of the world’s population is infected with M tuberculosis sounds alarming, only about 12% of these immune-sensitised individuals actually develop disease.20 Disease development is a function of the host’s immunocompetence; individuals with HIV, for example, are at increased risk of progression to active disease. However, disease development is also a reflection of the evolutionary strategy of M tuberculosis as a pathogen, which during human existence has needed to ensure transmission to the next host. M tuberculosis has to undertake a delicate balancing act: cause enough disease to ensure transmission but not so much that patients rapidly die, taking the pathogen’s progeny with them. The solution to this equation in modern, mostly urban high-density human populations might be very different than in historic low-density hunter gatherer human populations, which might be reflected in newly emerging strain clades.21 Because of this evolving situation, historic dogmas about the lifecycle of M tuberculosis are constantly being revised and revisited.

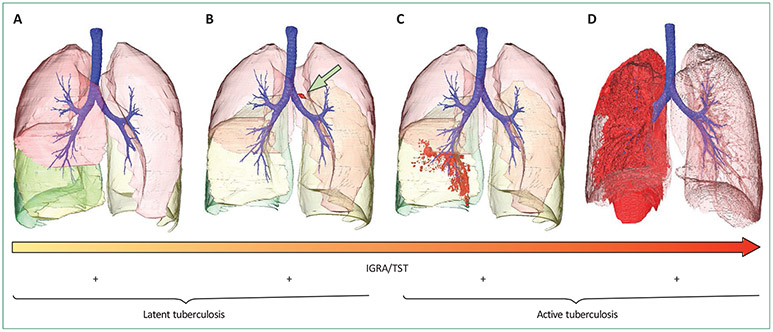

Results of studies in non-human primates, which are natural hosts of M tuberculosis, have shown several key features of what we would have previously referred to as latent tuberculosis infection.22 As in human beings, infection of cynomolgus macaques only occasionally proceeds directly to symptomatic infection in a fraction of animals; the remainder control the infection to a variable extent.23 The infected, asymptomatic animals seem to be clinically identical to human beings with latent tuberculosis, including showing a strong propensity for disease reactivation when treated with anti-TNF.24 Necropsy of non-human primates with latent tuberculosis shows a striking range of disease, ranging from subclinical infection that features active lesions with bacterial replication, to sterile granulomas or infected lymph nodes in individual animals.25 The variability of the extent of disease in these animals caused a substantial rethinking of what might constitute latent tuberculosis infection in human beings and led to the concept that latent infection might actually be a range of subclinical forms of the disease (figure 1).26,27 To identify the subset of patients with latent tuberculosis infection who are at high risk for progression and target prophylactic treatment to this small group of patients might ultimately be possible.28

Figure 1: Outcomes of infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

M tuberculosis infection has variable outcomes in different hosts. The individual (A) has been exposed but, through innate or adaptive immune function, has cleared the invading bacilli completely. Immunodiagnostic tests might be positive or negative in such people. This individual was interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) positive but is at no risk of relapse disease, and this outcome occurs in about 90% of infected individuals. We speculate that such individuals have sterilising immunity with no viable organisms in their tissues. Infected cells containing live M tuberculosis bacteria can also migrate to the draining lymph nodes (B; marked with an arrow); in non-human primates23 and human beings,26 this might often be accompanied by very small parenchymal lesions or infiltrates that are not visible by chest radiograph but might be visible on chest CT. The infection has progressed (C), but disease is fairly minimal, restricted to the right-lower lobe. Individuals with minor disease can report with variable symptoms or be asymptomatic and this state has been referred to as subclinical disease; non-human primates can similarly show acid-fast bacilli in gastric aspirates but seem clinically healthy, and are referred to as percolators. An individual has extensive consolidative disease throughout the right posterior and apical segments and lower lobe (D). Some individuals have recurrent active tuberculosis, but mechanisms underlying this susceptibility are unclear. Immunodiagnostic tests at any stage of disease might be negative because both tuberculin skin test (TST) and IGRA have suboptimum sensitivity for diagnosis of latent and active tuberculosis. Even for active tuberculosis, TST and IGRA sensitivity is around 80%.

Immunopathogenesis

After inhalation, bacteria are taken up by resident macrophages. After a series of complex interactions with the host, including a delay in onset of adaptive immunity, more macrophages are recruited to the site, specific T cells begin to accumulate, and a granuloma is formed (appendix). Although granulomas are typically thought to be protective, studies in infected zebrafish have highlighted the dynamic nature of these cellular granulomatous lesions and suggest that the granuloma additionally functions as a protective niche that enables bacterial replication.29 The fate of individual granulomas, even in one person, seems to depend on local factors. If too much local inflammation occurs, the granuloma begins to form a centralised area of necrosis that can ultimately liquefy, providing a rich source of infectious organisms for transmission. The local and dynamic nature of the outcome of infection in individual granulomas has been shown by serial PET–CT scanning in patients with active tuberculosis who were not responding to therapy.30 The cellular immunology of the host response to tuberculosis infection has been reviewed extensively.31 However, poor understanding of the nature of protective immunity to tuberculosis was highlighted by the failure of a large phase 3 vaccine trial.32 Understanding is needed of why most individuals never develop disease. Interest has been renewed in study of the 10–20% of individuals who are highly exposed but who never develop immune sensitisation.33 Finally, human challenge studies with Bacille-Calmette-Guérin (BCG) might provide additional insight into these questions.34 Key aspects about the pathogenesis of drug-resistant tuberculosis are outlined in the appendix.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of latent tuberculosis

Commercially available tests used to diagnose latent tuberculosis, and relevant readouts, are outlined in the appendix. In low-burden settings, guidelines have little agreement about which immunodiagnostic tests to use in close contacts of index cases, in immune-compromised people, and in some recent immigrants to low-incidence settings.35 Generally, in low-incidence settings, guidelines advocate exclusion of active tuberculosis and then recommend chemoprophylaxis on the basis of results of immunodiagnostic tests (either tuberculin skin test [TST] or interferon gamma release assay [IGRA], as advocated in the WHO guideline, or TST followed by IGRA) in tandem with risk stratification (eg, infectiousness of the index case, or age of the contact).36-38 Immune-compromising conditions, including HIV co-infection, reduces the sensitivity of TST and IGRA39 and lowers the cutoff for a positive TST (5 mm rather than 10 mm induration). Replacement of TST by IGRA is not recommended in middle-to-high incidence settings.38

Diagnosis of active tuberculosis

Global diagnostic capacity is low, and the case detection rate is suboptimum (64% in 2013).5 Expansion of active, rather than passive, case finding is needed to close the detection gap. Diagnosis of latent tuberculosis, optimum passive case finding approaches, groups to be targeted for active case finding, and effect on mortality and disease burden are outlined in panel 1.39-53 A community- based, low-cost, sensitive, user-friendly, high-throughput, and same-day point-of-care screening (triaging) test for tuberculosis is clearly needed.40 Such tests should have high sensitivity and negative predictive values, and should be rule-out tests. By contrast, more specific rule-in tests, which include detection of drug resistance (figure 2), could be done at centralised health-care centres (eg, microscopy centres and district hospitals). Notably, around 15% of the burden of tuberculosis is due to extrapulmonary tuberculosis (40–50% in the context of HIV co-infection), and a non-sputum-orientated diagnostic strategy is also needed (panel 1). Thus, ideally a non-sputum-based point-of-care test that can be used to diagnose all forms of tuberculosis is needed.

Panel 1: Diagnosis of latent and active tuberculosis.

Diagnosis of latent tuberculosis

Diagnosis of latent tuberculosis cannot be made with certainty, and mycobacterial load in people with presumed latent tuberculosis is not measurable

The likelihood of latent tuberculosis is inferred indirectly through quantifying the effector memory T-cell response in the skin (tuberculin skin test [TST] and RD-1-specific skin tests, such as C-TB)39,40 or the blood (interferon gamma release assays [IGRAs], Quantiferon Gold In-Tube and Plus, and TSPOT-TB; appendix)

Detectable memory T cells might signify active tuberculosis, previous tuberculosis, recent or remote exposure, latent tuberculosis, or exposure to specific environmental mycobacteria;41 therefore, neither IGRAs nor TST can distinguish latent from active tuberculosis

Results of randomised controlled trials suggest that treatment of TST-positive people reduces the short-term risk of tuberculosis development by about 70%42

Surrogate performance measures suggest that IGRA sensitivity in active tuberculosis is around 80%,43 specificity is better than in TST (especially when Bacille-Calmette-Guérin is administered after birth),44 IGRA reversion occurs spontaneously in a substantial number of cases,45,46 and short-term positive predictive value for active tuberculosis is poor (~1–2%) for IGRA and TST47,48

A research priority is to identify which patients with latent tuberculosis are at high risk of progression to active tuberculosis

Diagnosis of active tuberculosis

Passive case finding strategy

Passive case finding (symptom-triggered testing in people presenting at health-care facilities) fails to detect 40–50% of the total burden49

Optimum testing algorithms are context-specific (dependent on tuberculosis prevalence, HIV and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis prevalence, affordability, cost-effectiveness thresholds, and access to diagnostic methods and capacity)49,50

Active case finding strategy

Targeted screening of high-risk groups is recommended (close contacts, people with HIV, prisoners, miners [especially silica-exposed miners], people with untreated fibrotic chest radiograph lesions, people in high prevalence settings [>1% prevalence of tuberculosis], people passively seeking health care, and people in shelters, slums, and shantytowns, where several risk factors predominate)49

The predictive value of different screening algorithms is outlined in detail by WHO49

Results of modelling studies suggest that improved point-of-care diagnostics could have transformative effects only if used in the context of targeting screening and active case finding51

On the basis of three systematic reviews, only limited or poor quality evidence suggests that smear-microscopy-based active case finding detects earlier and less severe disease, and affects disease burden or outcomes49

Improved methods and approaches for active case finding are urgently needed to minimise transmission and increase detection

Limitations of sample collection

A strategy relying on spontaneously expectorated sputum is inadequate in about one-third of tuberculosis cases (more inadequate in children and HIV co-infection) because of several factors (eg, extrapulmonary tuberculosis cases [~15%], poor quality sputum samples, suboptimum sputum volumes, bacillary concentrations below the test detection threshold, or inability to obtain sputum [~10% of cases])

Alternative sampling techniques might be needed

(eg, sputum induction, bronchoscopy, gastric aspiration, and organ-specific aspiration or biopsy)

Motivation and instruction for health-care workers about how to obtain an adequate sputum sample is crucial,52 and is the preferred first step in people with sputum-scarce or smear-negative tuberculosis53

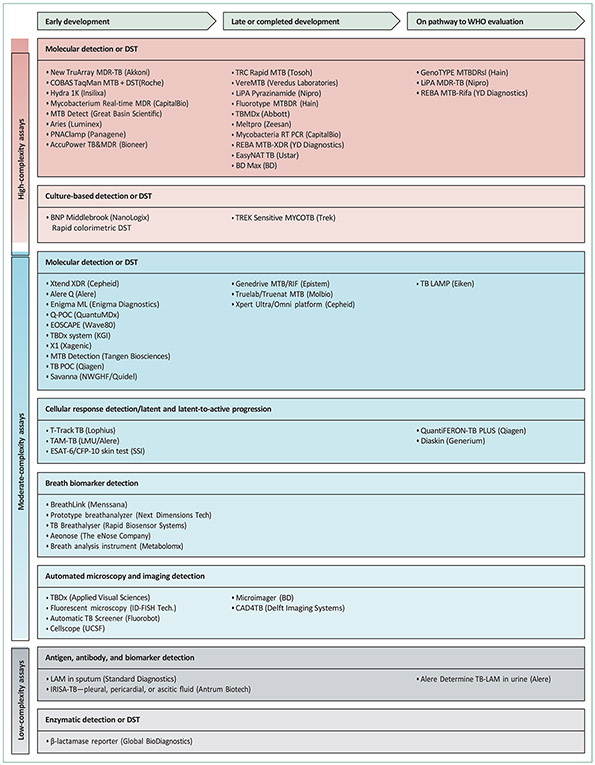

Figure 2: Summary of diagnostic tests in various phases of development.

Phases of development include early prototype stage, locked in design phase, commercially available, and on the pathway to WHO evaluation. Drugs are classified according to assay complexity. DST=drug susceptibility testing. MDR=multidrug-resistant. TB=tuberculosis. MTB=Mycobacterium tuberculosis. XDR=extensively drug-resistant. Coproduced with the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND).

Despite suboptimum sensitivity (~50%; limit of detection of ~104 organisms per mL), smear microscopy is the standard of care in most high-burden settings. To minimise patient dropout, at the cost of a negligible decrease in diagnostic yield, same-day microscopy (two samples collected at the same visit) is recommended.54 Sample centrifugation and fluorescence microscopy improves sensitivity by around 10%.55 Light-emitting-diode

(LED) microscopy (appendix), endorsed and recommended by WHO, has several cost and operational advantages.56 Automated high-throughput smear microscopy is under investigation.

Automated liquid culture (limit of detection of ~10 organisms per mL)57 is widely regarded as the gold standard confirmatory test for diagnosis and is more sensitive and rapid, but more costly and prone to contamination, than solid media.58 The traditional gold standard for phenotypic drug susceptibility testing, the proportion method with solid agar (1% threshold), is being superseded by standardised methods such as MGIT 960 (BD). In-house methods include microscopic observation of drug susceptibility, nitrate reductase assay (NRA), and colorimetric redox indicator assays (CRI).59 Choice of optimum method is dependent on context and resources.

Commercially available confirmatory tests include various nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), some of which include testing for drug resistance (appendix). Sputum samples can be directly assessed with the WHO-endorsed Gene Xpert MTB/RIF60 and Hain MTBDRplus assays.61,62 The Xpert assay works well for patients with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis and for specific forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis (meningitis in people with HIV63 and lymphadenitis, but not pleural, pericardial, or abdominal tuberculosis).60,64 Sensitivity of Xpert was around 89% in smear-positive and around 67% in smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis,65 with high specificity, and the level of detection in sputum is around 150 organisms per mL.66 The Xpert assay could feasibly be done by minimally trained health-care workers in peripheral facilities.67 Xpert is cost effective in endemic settings68 and enables rapid diagnosis of rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (thus potentially affecting transmission). However, Xpert is unable to detect isoniazid-mono-resistant tuberculosis, might give a positive result after completion of treatment,69 and cannot be used for treatment monitoring. Controlled trials have failed to show reductions in morbidity,67 mortality,70,71 or tuberculosis burden.67,70,71 In populations with an MDR tuberculosis prevalence of less than 10%, the positive predictive value for rifampicin resistance is likely to be less than 85%, and confirmatory testing with an alternative method is advisable.72 The decision of whether to continue MDR tuberculosis treatment when drug susceptibility results are discordant is challenging because of hetero-resistance (the presence, within a larger population of fully susceptible mycobacteria, sub-populations with lesser susceptibility) and might be guided by rpoB gene sequencing and clinical features (eg, presence of risk factors for MDR tuberculosis).

Several next-generation NAAT technologies are in advanced stages of development (appendix), including Xpert cartridges with alternative technology able to detect second-line drug resistance. Genotypic drug- resistance tests, including to second-line drugs, might be undertaken with the Hain MTBDRs/ assay (with isolates or smear-positive sputum),73 array-based methods, or targeted or next-generation whole-genome sequencing. The feasibility and effect of rapid detection of drug resistance with genome sequencing74 needs prospective validation.

The Determine urine lipoarabinomannan (LAM) point- of-care lateral flow assay (appendix) is a low-cost useful rule-in test in people with HIV with a CD4 cell count of less than 200 cells per μL, especially in those who are sputum scarce or smear negative.75,76 Sensitivity increases with decreasing CD4 cell count.77 whether the urine LAM assay can affect mortality in HIV-endemic settings is unclear. Several other protein and nucleic acid candidate antigenic targets have been identified in urine.78

Alternative novel approaches to diagnosis (figure 2) that need validation include detection of volatile organic compounds in breath and sweat,79 targeted fluorescent- labelled tuberculosis-specific enzyme-based probes,40 blood-based host transcriptomic signatures,80,81 and computer-assisted chest radiograph diagnosis.40 Remark- ably, immunodiagnostic tests with serum-based antibody and antigen detection are still used in endemic countries despite their proven poor accuracy and WHO’s recommendations against their use.82,83

Clinical presentation of tuberculosis

The clinical presentation of tuberculosis has been reviewed in detail elsewhere. The clinical manifestations of tuberculosis are protean because any organ might involved. The classic symptoms of fever, drenching night sweats, and weight loss, accompanied by symptoms from the involved organs, are important clues to the presence of tuberculosis. Several clinical presentations of tuberculosis are outlined in the appendix.

Treatment of tuberculosis

Drug-sensitive tuberculosis

The evidence base for the recommended regimen for drug-sensitive tuberculosis (isoniazid and rifampicin for 6 months, together with pyrazinamide and ethambutol for the first 2 months) was established four decades ago, but the regimen is highly effective. Although called short course, the regimen’s main drawback is the duration of therapy. The proportion of patients defaulting therapy increased linearly after 4 weeks and varied between 7% and 53·6% in a systematic review.84

Directly observed therapy (DOT) was widely implemented by tuberculosis control programmes as a strategy to improve adherence and reduce default without good evidence that it was effective. Clinic-based DOT, which is widely practised, substantially increases costs to both providers and patients,85 and is a paternalistic method of adherence support. Proponents of DOT argue that it is “the only current documented means” to ensure cure and limit emergence of drug resistance.86 However, a meta-analysis comparing outcomes of DOT with self-administered therapy reported no difference in cure, relapse, or acquired drug resistance, but DOT decreased the proportion of patients defaulting therapy.87 WHO no longer recommends universal DOT and encourages a flexible approach to supervision of treatment in health-care facilities, the workplace, or the community, with the exception of selected populations (eg, injection drug users or prisoners) for whom DOT is still recommended.88

In resource-limited settings, therapy is monitored in patients with sputum smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis by repetition of the sputum smear at 2 months and 5 months. Treatment success is defined by completion of therapy with negative follow-up sputum smears. The median time to sputum culture conversion in sputum-smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis is 4–6 weeks, but is longer in African patients after adjustment for confounders.89 The observed lower rifampicin concentrations in African patients,90 which has been linked to the high allele frequency of a polymorphism the SLCO1B1 gene,91 could explain slower culture conversion times.

Short course therapy is generally well tolerated. The most serious adverse drug reaction is drug-induced liver injury, which can be caused by rifampicin, isoniazid, or pyrazinamide. The reported incidence of drug-induced liver injury varies from 5% to 33%,92 but most studies include a large proportion of patients with asymptomatic elevation of transaminases. Transient elevation of transaminases occurs commonly in the first few weeks of therapy, a phenomenon termed hepatic adaptation. Inexperienced clinicians might inappropriately interrupt or change therapy in patients with hepatic adaptation. Routine monitoring of liver function tests is not recommended, even in high-income countries,92 unless the patient is at high risk of hepatotoxicity (eg, alcohol misuse, chronic viral hepatitis, or pregnancy). Potentially hepatotoxic drugs should be withdrawn if clinical hepatitis occurs, and two second-line drugs added to ethambutol. When hepatitis is settling, re-challenge with rifampicin and isoniazid, and possibly also with pyrazinamide, should be considered. Outcomes of three re-challenge regimens did not differ significantly, and the regimens were successful in about 90% of participants in a randomised controlled trial.93 Our preference is to use the American Thoracic Society’s re-challenge regimen92 because it is fairly simple.

Adjunctive corticosteroids

Adjunctive corticosteroids reduce inflammation and improve outcomes in some forms of tuberculosis. Corticosteroids reduce death and residual neurological deficit in tuberculous meningitis.94 A meta-analysis95 of trials in the rifampicin era in all forms of tuberculosis reported a mortality benefit for corticosteroids in patients with tuberculous meningitis and pericarditis, but not in those with pulmonary tuberculosis. However, no mortality benefit was reported for corticosteroids in patients with tuberculous pericarditis in the large IMPI trial,96 which was published after the meta-analysis. Participants randomised to corticosteroids in the IMPI trial had a three-fold increased risk of developing cancers, which were mostly HIV associated—an important reminder of the dangers of corticosteroids in patients who are already immune suppressed. At present, evidence is insufficient to support use of adjunctive corticosteroids in any form of tuberculosis in patients with HIV.

HIV co-infection

Patients with HIV-associated tuberculosis have an increased recurrence rate, which results from reinfection rather than relapse.97 Whether short course therapy for tuberculosis is more toxic in patients with HIV than in those without HIV is unknown.98 Assigning causality of adverse events to individual drugs is difficult in patients with HIV because they often have comorbidities and take many concomitant medications.

Rifampicin strongly induces many drug-metabolising enzymes and transporters. Concentrations of many antiretroviral drugs are reduced by coadministered rifampicin, necessitating increased antiretroviral doses or switching from rifampicin to rifabutin,99 which is a weak inducer.

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is an immunopathological response to subclinical or treated tuberculosis, typically presenting about 2 weeks after starting antiretroviral therapy (ART), with fever accompanied by new, recurrent, or worsening lymph node enlargement, pulmonary infiltrates, or serositis (appendix). Incidence of IRIS increases exponentially with decreasing CD4 cell counts.100 Deferring ART initiation to 8 weeks rather than 2 weeks after starting therapy for tuberculosis reduces risk of IRIS, but increases risk of death in patients with CD4 cell counts of less than 50 cells per μL.101 Tuberculosis–IRIS has a low mortality,100 except for cases with neurological involvement.102 Tuberculosis–IRIS is characterised by increased concentrations of pro- inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines,103 and of pro-inflammatory markers of innate and myeloid cell activation.104 Data from studies in mice of IRIS due to mycobacterial infections suggest that increased responsiveness of infected macrophages to signalling from rapid restoration of mycobacterial antigen-specific CD4 T lymphocytes underlies the observed immunopathology.105 Prednisone reduced duration of hospital admissions and the need for therapeutic procedures in a placebo-controlled trial106 of participants with tuberculosis–IRIS.

Treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis and emergence of incurable strains

Principles of treatment for MDR and XDR tuberculosis are outlined in panel 2.107-121 The recommended MDR tuberculosis regimen is toxic, poorly tolerated (appendix), prolonged (up to 24 months), and not based on data from controlled trials. Treatment success rates in many countries are only around 50%.6 The load of MDR tuberculosis in endemic countries has necessitated treatment decentralisation to peripheral clinics, in which outcomes are equivalent or better.122 Emergence of incurable tuberculosis (XDR tuberculosis failures and resistance beyond XDR tuberculosis), totally drug-resistant (TDR) tuberculosis, can result in community-based transmission of untreatable strains,7 and has raised legal, ethical, and logistical dilemmas about placement of patients and their rights to unrestricted travel and work.123

Panel 2: Medical and surgical management of drug-specific resistance profiles.

Isoniazid mono-resistant tuberculosis

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis

Ideally use at least four drugs to which the strain has proven or likely susceptibility (drugs previously taken for 3 months or longer are generally avoided; excludes pyrazinamide and ethambutol)110

Use a backbone of a later-generation fluoroquinolone (eg, moxifloxacin or levofloxacin), plus an injectable drug (amikacin, kanamycin, or capreomycin)110

Add any first-line drug and additional group 4 drugs (eg, cycloserine, terizidone, ethionamide, or prothionamide) to which the isolate is susceptible

Injectable drugs are generally used for 6–8 months, and 21–24 months of treatment is recommended110

Oxazolidinones (linezolid) can be used for an effective regimen in fluoroquinolone-resistant MDR (and extensively drug-resistant [XDR]) tuberculosis, but monitoring for toxicity (neuropathy and bone marrow depression) is needed111-113

Bedaqualine or delaminid can be added to the regimen if toxicity or high-grade resistance precludes a regimen containing four or more drugs likely to be effective (both drugs prolong QT interval, thus needing monitoring)114,115

Psychosocial and financial support are crucial to maintain adherence

Patients should be monitored for adverse drug reactions, which are common116

A single drug should not be added to a failing regimen

XDR tuberculosis and resistance beyond XDR tuberculosis

Regimens should be based on prevailing patterns of drug resistance and on similar principles to those outlined for MDR tuberculosis (use of four or more drugs is likely to be effective)

Adverse events such renal failure, hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia, and hearing loss are associated with capreomycin116

Differential susceptibility to fluoroquinolones can occur;117 clofazamine, linezolid, and high-dose isoniazid (guided by genotypic testing) might be useful to optimise the regimen118

Other group 4 (oral bacteriostatic second-line drugs) and group 5 drugs (drugs with unclear efficacy or role in treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis)6 are often used, but their effectiveness is uncertain

Surgical management of MDR and XDR tuberculosis

Candidates for surgery include patients with unilateral disease (or apical bilateral disease in selected cases) with adequate lung function who have not responded to medical treatment119

Surgical intervention might be appropriate in patients at high risk of relapse or treatment failure despite response to therapy (eg, XDR tuberculosis or resistance beyond XDR tuberculosis)119

Facilities for surgical lung resection are restricted and often inaccessible

PET–CT might be useful to clarify the presence of contralateral disease and might have prognostic use, but its role in this context needs validation (PET–CT images are shown in the appendix)120,121

New antituberculosis drugs and regimens

After decades of stagnation, a range of new antituberculosis drugs (appendix) are in clinical development (table 2), two of which, bedaquiline and delamanid, have been registered for use in drug-resistant tuberculosis, whereas others such as SQ109 have shown limited efficacy in early studies.124 Several antimicrobial drugs developed for other infectious diseases have useful activity against M tuberculosis. These so-called repurposed drugs are the later-generation fluoroquinolones, moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, and gatifloxacin; the oxazolidinone, linezolid; and the anti-leprosy drug, clofazimine.

Mouse models are important in preclinical development of new drugs and regimens. Although mouse models of tuberculosis do not closely resemble human disease, they are often used to assess duration of therapy. Clinical development of new drugs and regimens is undertaken in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis by assessing their effect on sputum bacillary concentrations for 7–14 days in early bactericidal activity studies, or by assessing sputum culture conversion rates for 8 weeks. Although both approaches have limitations, they are valuable tools to identify optimum doses of individual drugs and to select drug combinations.

Shorter regimens for drug-sensitive tuberculosis

One or more drugs used in short course regimens— rifampicin and pyrazinamide—will be used in novel regimens to shorten duration of treatment. Results of early bactericidal activity studies show that increased doses of rifampicin or rifapentine increase the rate of decline in quantitative sputum cultures.125-127 The concentrations of rifampicin and pyrazinamide were key determinants of sterilising activity for 8 weeks in a study of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis,128 suggesting that increased doses of pyrazinamide and rifampicin should be used in future studies of treatment-shortening regimens. Increased exposures to rifapentine, a long acting rifamycin, are likewise associated with sputum culture conversion within 8 weeks.127 Several novel regimens with fluoroquinolones, bedaquiline, or pretomanid, or a combination, have shown potential to shorten treatment duration in phase 2 clinical trials.129,130

Three randomised controlled trials131-133 of 4-month regimens shown in mice to need shorter duration of therapy with the fluoroquinolones gatifloxacin or moxifloxacin (together with rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and isoniazid, or ethambutol) all showed higher relapse rates than standard short course therapy. Sputum culture conversion was faster in the moxifloxacin groups than in the standard therapy group in the REMoxTB trial,133 as was the case in the 8-week studies,134 which prompted treatment shortening trials. However, the larger sample size in the REMoxTB trial enabled increased precision to detect the magnitude of difference in sputum culture conversion and suggested that treatment shortening by about a month might be possible with moxifloxacin- based regimens.133 It is unlikely that phase 3 treatment- shortening trials will be done with 5-month regimens, and the search for more potent regimens continues.

New drugs and regimens for drug-resistant tuberculosis

New drugs and regimens are urgently needed for MDR and XDR tuberculosis. Hiwgh-dose isoniazid resulted in faster sputum culture conversion in a small randomised controlled trial,135 but caused a ten-fold increased risk of peripheral neuropathy and is likely to only benefit patients with low-level isoniazid resistance. A 9-month regimen including clofazimine and high-dose isoniazid resulted in high cure rates in a non-randomised cohort study136—results of a randomised controlled trial comparing this regimen to the standard 21–24-month regimen are awaited. Bedaquiline,137 delamanid,138 and linezolid139 have all shown improved sputum culture conversion rates when added to optimised background therapy in patients with drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. Clarification of the optimum combination of drugs and duration of therapy for MDR tuberculosis needs further studies (table 2), but less toxic, shorter, and more effective regimens are likely to be developed in the near future.

Prognosis and post-tuberculous lung disease

The 10-year case fatality rates are 70% for untreated smear-positive tuberculosis and 20% for smear-negative tuberculosis.2 The corresponding case fatality rates for people with HIV are 83% for smear-positive patients and 74% for smear-negative patients.2 Increasing age, more extensive disease, and HIV co-infection are associated with increased mortality. Mortality with treatment is around 2·5% for people without HIV and around 14% in people with HIV.140,141

Pulmonary tuberculosis can cause substantial chronic morbidity owing to residual post-tuberculous bron- chiectasis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), aspergillomas, and lung destruction (appendix).142 These disorders cause substantial and progressive lung disability, culminating in respiratory failure or massive haemoptysis. Aspergillomas occur in residual cavities (examples from explanted lungs shown in the appendix) and might cause massive haemoptysis needing surgery or bronchial artery embolisation (the optimum management strategy is unclear), or chronic invasive aspergillosis.143 Case series have reported encouraging results with voriconazole in patients with aspergillomas who refuse, or are unfit for, surgery144 but controlled data are needed. In developing countries, tuberculosis is an important cause of COPD, mainly owing to small airways disease and gas trapping rather than emphysema.145 The natural history of post- tuberculous COPD and responses to conventional COPD treatment are unclear. Patients with progressive post-tuberculous bronchiectasis are often managed erroneously with repeated courses of empiric treatment for tuberculosis. The pathogenesis of dysfunctional extracellular matrix deposition and clearance mech- anisms, lung cavitation,146 and lung remodelling due to tuberculosis are incompletely understood.143 immuno- therapeutic approaches to minimisation or prevention of cavitation and fibrosis, both of which might result in post-tuberculous lung disease, need further study.

Prevention of tuberculosis

Preventive therapy

Preventive therapy for people at high risk of tuberculosis is an important component of the strategies to eliminate tuberculosis outlined by WHO in their post-2015 strategy.147 In high-burden countries, preventive therapy is usually limited to people with HIV and children aged less than 5 years with household contacts. In low-burden countries, immigrants from high-burden countries and all close contacts with latent tuberculosis are targeted for preventive therapy. The most widely used regimen for preventive therapy in people with and without HIV is isoniazid for 6–12 months, with generally increased efficacy with longer duration.148

The efficacy of preventive therapy in HIV-infected adults is determined by their TST status149 Decreasing CD4 lymphocyte counts in patients with untreated HIV infection are associated with increased risk of false- negative TSTs150 and tuberculosis.151 The fact that TST positivity is associated with benefit from preventive therapy is difficult to explain because the test’s ability to diagnose latent tuberculosis infection is poorest in people at highest risk of tuberculosis. In people with HIV infection, some extent of cellular immunity to tuberculosis, for which a positive TST is a proxy, seems to be needed for preventive therapy to be effective. Unfortunately, the duration of benefit after isoniazid preventive therapy is short.152 WHO recommends isoniazid for 36 months for people with positive or unknown TST status,153 after the results of the BOTUSA study,154 which showed that 36 months of isoniazid was substantially more effective for prevention of tuberculosis than 6 months in participants with positive TST status. It is important to rule out active tuberculosis before initiation of preventive therapy in HIV-infected people to limit selection of drug resistance. Absence of the classic tuberculosis symptoms of fever, night sweats, and weight loss to exclude active tuberculosis perform less well in people on ART.155 isoniazid preventive therapy reduces the risk of tuberculosis in people receiving ART, but, unlike in trials in the pre-ART era, the benefit was seen irrespective of TST status.156

Interest in the use of rifamycin-based regimens for preventive therapy is increasing. 3-month regimens of rifampicin or rifapentine plus isoniazid are generally well tolerated, and are as effective as 6–12 months of isoniazid in people with or without HIV.148 Results from a mathematical model suggest that rifamycin-based regimens might cure latent tuberculosis in people with HIV, whereas isoniazid monotherapy does not.152

Contact tracing and infection control

Limitation of transmission of airborne pathogens such as M tuberculosis in health-care facilities is challenging. Rapid diagnosis and prompt initiation of effective therapy are the foundations of tuberculosis infection control. When close contacts should be traced, the potential gains, key points for contact tracing, and evidence for efficacy of infection control interventions are outlined in panel 3.

Panel 3: Prevention of tuberculosis—contact tracing, infection control, and vaccines.

Close contacts

Identification and early treatment of contacts with active tuberculosis should reduce morbidity and risk of transmission, but is poorly implemented in most high-burden countries

WHO recommends investigation of close contacts for active tuberculosis or latent infection when the index case has any one of the following characteristics: pulmonary tuberculosis with positive sputum smears, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, a child aged less than 5 years, or HIV co-infection

Prevalence of active tuberculosis is 3·1% in low-to-middle-income countries and 1·4% in high-income countries, and prevalence of latent tuberculosis in contacts was 51·5% in low-to-middle-income countries and 28·1% in high-income countries; household contact tracing would reduce tuberculosis incidence by an estimated 2% per year if cases of active tuberculosis were identified and treated

Infection control

Very limited evidence exists for efficacy of the various interventions recommended for personal and environmental protection

Patients with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis should be nursed in negative-pressure isolation rooms with at least 12 air changes per hour, which is not feasible in high-burden countries

WHO recommends natural ventilation in resource-limited settings; opening windows provides natural ventilation that exceeds 12 air changes per hour, and wind-driven roof turbines achieve a high number of air changes per hour and are not easily blocked by staff or patients

Personal protection with properly fitted face masks that have the capacity to filter droplet nuclei should be used by health-care staff exposed to patients with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis

Surgical face masks, which are much cheaper than N95 masks, reduce infectiousness when worn by patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis

Vaccines

Bacille-Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is effective at preventing severe childhood forms of tuberculosis but, for several reasons, protection wanes by adolescence

At present, 15 vaccine candidates are in clinical trials (appendix)

These vaccines are either designed to replace BCG (pre-exposure vaccine), be given in infancy or adolescence to augment BCG-mediated protection (prime–boost strategy), or to shorten or potentiate treatment (therapeutic vaccine)

Categories of vaccines include live attenuated Mycobacterium tuberculosis, re-engineered BCG, mycobacterial whole cells or extract, adjuvant-complexed single or fusion tuberculosis-specific proteins, and mycobacterial proteins expressed through a viral vector or plasmid DNA

Vaccine candidates have been selected on the basis of protection in animals (mycobacterial stasis in mice, guineapigs, and non-human primates) and their ability to induce T-helper-1-based CD4 T-cell immune responses in human beings; this approach is being questioned because MVA85A induced a very strong CD4 T-helper 1 response in early studies but failed to provide protection in the phase 2b clinical trial

Vaccine development is hindered by several challenges, including scarcity of correlates of protective immunity, poor correlation of efficacy between animals and human beings, and restricted funding and capacity for clinical trials

Several alternative approaches and vaccine concepts are being investigated, including alternative clinical trial and challenge models (including human), interrogation of infectious dose, use of non-protein antigens, and identification of alternative components of the immune system that might be relevant to host immunity (eg, innate and regulatory components, and revisiting the role of antibodies in protection)

The comprehensively referenced panel is available in the appendix.

Vaccines and research priorities

An effective tuberculosis vaccine is needed for eradication of tuberculosis. Even a vaccine of limited efficacy (~60%) delivered to just 20% of the population could save millions of lives.157 The effectiveness of existing vaccines, the planned assessment pipeline, new approaches, and other key aspects of tuberculosis vaccines are outlined in panel 3 and the appendix.

Research priorities in tuberculosis, the importance of operational and patient-centred research, and the importance of a health systems approach have been reviewed in detail elsewhere.158,159 key research priorities in terms of pathogenesis and transmission, diagnosis, drugs and treatment, vaccines, operational, economic and public health research, and cross-cutting themes are outlined in the appendix.

Conclusion

Incidence of tuberculosis is decreasing much more slowly than expected and it remains a global scourge. Encouragingly, after several decades of inertia, advances have been made in the form of several new diagnostics and drugs. However, these advances alone will not achieve the ambitious target set out in the End TB Strategy (appendix). A widely available low-cost screening test is urgently needed to improve detection rates, and an efficient new vaccine and more effective preventive therapy are needed to eradicate tuberculosis. However, these developments need an improved understanding of tuberculosis pathogenesis. In tandem, public health efforts are needed to reduce the major drivers of tuberculosis, including smoking, diabetes, biomass fuel exposure, and HIV co-infection. Finally, political stability and alleviation of poverty and overcrowding worldwide will be essential for eradication of tuberculosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Helen Wainwright, Graeme Meintjes, Qonita Said-Hartley, Sulaiman Moosa, and Gregory Calligaro for the radiographic and tissue section images in the appendix, and Grant Theron, Aliasgar Esmail, and Laurene Viljoen for assistance with specific inserts and manuscript processing.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

KD reports grants from Foundation of Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND), eNose Company, Statens Serum Institut, and bioMeriux, and grants and personal fees from ALERE, Oxford Immunotec, Cellestis (now Qiagen), Cepheid, Antrum Biotec, and Hain Lifescience. Additionally, KD has a patent “Characterisation of novel tuberculosis- specific urinary biomarkers” pending, a patent “A smart mask for monitoring cough-related infectious diseases” pending, and a patent “Device for diagnosing EPTB” issued. CEB reports grants from Cepheid, Hain Life science, YD Daignostics, and FIND. GM served on the data safety and monitoring board for Janssen for the TMC207 C208 and C207 phase 2 trials in patients with multidrug-resistant MDR tuberculosis, 2007–12.

Contributor Information

Keertan Dheda, Lung Infection and Immunity Unit, Division of Pulmonology and UCT Lung Institute, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.

Clifton E Barry, 3rd, Department of Medicine, and Institute of Infectious Disease and Molecular Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa; Tuberculosis Research Section, Laboratory of Clinical Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, USA.

Gary Maartens, Division of Clinical Pharmacology, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.

References

- 1.Comas I, Coscolla M, Luo T, et al. Out-of-Africa migration and Neolithic coexpansion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with modern humans. Nat Genet 2013; 45:1176–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tiemersma EW, van der Werf MJ, Borgdorff MW, Williams BG, Nagelkerke NJ. Natural history of tuberculosis: duration and fatality of untreated pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV negative patients: a systematic review. PLoS One 2011; 6: e17601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan F. The Forgotten Plague: how the battle against tuberculosis was won—and lost. Boston, MA: Back Bay Books, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen T, Dye C. Epidemiology. In: Davies PDO, Gordon SB, Davies G, eds. Clinical tuberculosis. 5th edn. Florida, USA: CRC Press, 2014:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global tuberculosis Report WHO. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dheda K, Gumbo T, Gandhi NR, et al. Global control of tuberculosis: from extensively drug-resistant to untreatable tuberculosis. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2: 321–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pietersen E, Ignatius E, Streicher EM, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet 2014; 383:1230–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berti E, Galli L, Venturini E, de Martini M, Chiappini E. Tuberculosis in childhood: a systematic review of national and international guidelines. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14 (suppl 1): S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perez-Velez CM, Marais BJ. Tuberculosis in children. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 348–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pai M, Menzies D. Interferon-gamma release assays for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection. In: Von Reyn FC, Baron E, eds. In UptoDate: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2014: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawn SD, Badri M, Wood R. Tuberculosis among HIV-infected patients receiving HAART: long term incidence and risk factors in a South African cohort. AIDS 2005; 19: 2109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lönnroth K, Castro KG, Chakaya JM, et al. tuberculosis control and elimination 2010–50: cure, care, and social development. Lancet 2010; 375:1814–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dye C, Glaziou P, Floyd K, Raviglione M. Prospects for tuberculosis elimination. Annu Rev Public Health 2013; 34: 271–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alland D, Kalkut GE, Moss AR, et al. Transmission of tuberculosis in New York City. An analysis by DNA fingerprinting and conventional epidemiologic methods.N Engl J Med 1994; 330:1710–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Small PM, Hopewell PC, Singh SP, et al. The epidemiology of tuberculosis in San Francisco. A population-based study using conventional and molecular methods. N Engl J Med 1994; 330: 1703–09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borgdorff MW, van Soolingen D. The re-emergence of tuberculosis: what have we learnt from molecular epidemiology? Clin Microbiol Infect 2013; 19: 889–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardy JL, Johnston JC, Ho Sui SJ, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and social-network analysis of a tuberculosis outbreak N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 730–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood R, Morrow C, Ginsberg S, et al. Quantification of shared air: a social and environmental determinant of airborne disease transmission. PLoS One 2014; 9: e106622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruciani M, Malena M, Bosco O, Gatti G, Serpelloni G. The impact of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 on infectiousness of tuberculosis: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33:1922–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vynnycky E, Fine PE. The natural history of tuberculosis: the implications of age-dependent risks of disease and the role of reinfection. Epidemiol Infect 1997;119:183–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Portevin D, Gagneux S, Comas I, Young D. Human macrophage responses to clinical isolates from the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex discriminate between ancient and modern lineages. PLoS Pathog 2011; 7: e1001307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robertson BD, Altmann D, Barry C, et al. Detection and treatment of subclinical tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2012; 92: 447–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capuano SV 3rd, Croix DA, Pawar S, et al. Experimental Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of cynomolgus macaques closely resembles the various manifestations of human M. tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun 2003; 71: 5831–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin PL, Myers A, Smith L, et al. Tumor necrosis factor neutralization results in disseminated disease in acute and latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection with normal granuloma structure in a cynomolgus macaque model. Arthritis Rheum 2010; 62: 340–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin PL, Ford CB, Coleman MT, et al. Sterilization of granulomas is common in active and latent tuberculosis despite within-host variability in bacterial killing. Nat Med 2014; 20: 75–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghesani N, Patrawalla A, Lardizabal A, Salgame P, Fennelly KP. Increased cellular activity in thoracic lymph nodes in early human latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189: 748–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barry CE 3rd, Boshoff HI, Dartois V, et al. The spectrum of latent tuberculosis: rethinking the biology and intervention strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol 2009; 7: 845–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esmail H, Barry CE 3rd, Young DB, Wilkinson RJ. The ongoing challenge of latent tuberculosis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2014; 369: 20130437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramakrishnan L. Revisiting the role of the granuloma in tuberculosis. Nat Rev Immunol 2012; 12: 352–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coleman MT, Chen RY, Lee M, et al. PET/CT imaging reveals a therapeutic response to oxazolidinones in macaques and humans with tuberculosis. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6: 265ra167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orme IM, Robinson RT, Cooper AM. The balance between protective and pathogenic immune responses in the TB-infected lung. Nat Immunol 2015; 16: 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dorhoi A, Kaufmann SH. Perspectives on host adaptation in response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis: modulation of inflammation. Semin Immunol 2014; 26: 533–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cobat A, Gallant CJ, Simkin L, et al. Two loci control tuberculin skin test reactivity in an area hyperendemic for tuberculosis. J Exp Med 2009; 206: 2583–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsumiya M, Satti I, Chomka A, et al. Gene expression and cytokine profile correlate with mycobacterial growth in a human BCG challenge model. J Infect Dis 2015; 211: 1499–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Denkinger CM, Dheda K, Pai M. Guidelines on interferon-γ release assays for tuberculosis infection: concordance, discordance or confusion? Clin Microbiol Infect 2011; 17: 806–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.NICE. Tuberculosis: clinical diagnosis and management of tuberculosis, and measures for its prevention and control. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Updated guidelines for using interferon gamma release assays to detect mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. MMWR 2010; 59:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.WHO. Guidelines on the management of latent tuberculosis infection. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pai M, Denkinger CM, Kik SV, et al. Gamma interferon release assays for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014; 27: 3–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dheda K, Ruhwald M, Theron G, Peter J, Yam WC. Point-of-care diagnosis of tuberculosis: past, present and future. Respirology 2013; 18: 217–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dheda K, van Zyl Smit R, Badri M, Pai M. T-cell interferon-gamma release assays for the rapid immunodiagnosis of tuberculosis: clinical utility in high-burden vs. low-burden settings. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2009; 15:188–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferebee SH, Mount FW. Tuberculosis morbidity in a controlled trial of the prophylactic use of isoniazid among household contacts. Am Rev Respir Dis 1962; 85: 490–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sester M, Sotgiu G, Lange C, et al. Interferon-γ release assays for the diagnosis of active tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2011; 37:100–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farhat M, Greenaway C, Pai M, Menzies D. False-positive tuberculin skin tests: what is the absolute effect of BCG and non-tuberculous mycobacteria? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2006; 10:1192–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dorman SE, Belknap R, Graviss EA, et al. , and the tuberculosis Epidemiologic Studies Consortium. Interferon-γ release assays and tuberculin skin testing for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in healthcare workers in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189: 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adams S, Ehrlich R, Baatjies R, et al. Incidence of occupational latent tuberculosis infection in South African healthcare workers. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 1364–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Nienhaus A. Predictive value of interferon-γ release assays and tuberculin skin testing for progression from latent TB infection to disease state: ameta- analysis. Chest 2012; 142: 63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rangaka MX, Wilkinson KA, Glynn JR, et al. Predictive value of interferon-γ release assays for incident active tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:45–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.WHO. Systematic screening for active tuberculosis: Principles and recommendations. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.WHO. Guidelines for intensified tuberculosis case-finding and isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in resource- constrained settings. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun AY, Pai M, Salje H, Satyanarayana S, Deo S, Dowdy DW. Modeling the impact of alternative strategies for rapid molecular diagnosis of tuberculosis in Southeast Asia. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 178:1740–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khan MS, Dar O, Sismanidis C, Shah K, Godfrey-Faussett P. Improvement of tuberculosis case detection and reduction of discrepancies between men and women by simple sputum- submission instructions: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 369:1955–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peter JG, Theron G, Pooran A, Thomas J, Pascoe M, Dheda K. Comparison of two methods for acquisition of sputum samples for diagnosis of suspected tuberculosis in smear-negative or sputum- scarce people: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1: 471–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.WHO. Same-day diagnosis of tuberculosis by microscopy. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steingart KR, Henry M, Ng V, et al. Fluorescence versus conventional sputum smear microscopy for tuberculosis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2006; 6: 570–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whitelaw A, Peter J, Sohn H, et al. Comparative cost and performance of light-emitting diode microscopy in HIV-tuberculosis-co-infected patients. Eur Respir J 2011; 38: 1393–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Zyl-Smit RN, Binder A, Meldau R, et al. Comparison of quantitative techniques including Xpert MTB/RIF to evaluate mycobacterial burden. PLoS One 2011; 6: e28815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cruciani M, Scarparo C, Malena M, Bosco O, Serpelloni G, Mengoli C. Meta-analysis of BACTEC MGIT 960 and BACTEC 460 TB, with or without solid media, for detection of mycobacteria. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42: 2321–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.WHO. Noncommercial culture and drug-susceptibility testing methods for screening patients at risk for multidrugresistant tuberculosis. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.WHO. Xpert MTB/RIF implementation manual. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 61.WHO. The use of molecular line probe assay for the detection of resistance to second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barnard M, Gey van Pittius NC, van Helden PD, Bosman M, Coetzee G, Warren RM. The diagnostic performance of the GenoType MTBDRplus version 2 line probe assay is equivalent to that of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50: 3712–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patel VB, Theron G, Lenders L, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of quantitative PCR (Xpert MTB/RIF) for tuberculous meningitis in a high burden setting: a prospective study. PLoS Med 2013; 10: e1001536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pandie S, Peter JG, Kerbelker ZS, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of quantitative PCR (Xpert MTB/RIF) for tuberculous pericarditis compared to adenosine deaminase and unstimulated interferon-γ in a high burden setting: a prospective study. BMC Med 2014; 12:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Steingart KR, Schiller I, Horne DJ, Pai M, Boehme CC, Dendukuri N. Xpert® MTB/RIF assay for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 1: CD009593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Theron G, Peter J, van Zyl-Smit R, et al. Evaluation of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in a high HIV prevalence setting. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 184:132–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Theron G, Zijenah L, Chanda D, et al. , and the TB-NEAT team. Feasibility, accuracy, and clinical effect of point-of-care Xpert MTB/ RIF testing for tuberculosis in primary-care settings in Africa: a multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2014; 383: 424–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Langley I, Lin HH, Egwaga S, et al. Assessment of the patient, health system, and population effects of Xpert MTB/RIF and alternative diagnostics for tuberculosis in Tanzania: an integrated modelling approach. Lancet Glob Health 2014; 2: e581–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Friedrich SO, Rachow A, Saathoff E, et al. , and the Pan African Consortium for the Evaluation of Anti-tuberculosis Antibiotics (PanACEA). Assessment of the sensitivity and specificity of Xpert MTB/RIF assay as an early sputum biomarker of response to tuberculosis treatment. Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1: 462–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cox HS, Mbhele S, Mohess N, et al. Impact of Xpert MTB/RIF for TB diagnosis in a primary care clinic with high TB and HIV prevalence in South Africa: a pragmatic randomised trial. PLoS Med 2014; 11: e1001760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Churchyard GJ, Stevens WS, Mametja LD, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF versus sputum microscopy as the initial diagnostic test for tuberculosis: a cluster-randomised trial embedded in South African roll-out of Xpert MTB/RIF. Lancet Glob Health 2015; 3: e450–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.WHO. Rapid Implementation of the Xpert MTB/RIF diagnostic test: Technical and operational ‘How-to’ Practical considerations. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Theron G, Peter J, Richardson M, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of the GenoType®MTBDRsl assay for the detection of resistance to second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 10: CD010705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Köser CU, Bryant JM, Becq J, et al. Whole-genome sequencing for rapid susceptibility testing of M. tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 290–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Peter JG, Theron G, van Zyl-Smit R, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a urine lipoarabinomannan strip-test for TB detection in HIV- infected hospitalised patients. Eur Respir J 2012; 40:1211–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lawn SD, Dheda K, Kerkhoff AD, et al. Determine TB-LAM lateral flow urine antigen assay for HIV-associated tuberculosis: recommendations on the design and reporting of clinical studies. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13: 407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Minion J, Leung E, Talbot E, Dheda K, Pai M, Menzies D. Diagnosing tuberculosis with urine lipoarabinomannan: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2011; 38:1398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Young BL, Mlamla Z, Gqamana PP, et al. The identification of tuberculosis biomarkers in human urine samples. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 1719–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chambers ST, Scott-Thomas A, Epton M. Developments in novel breath tests for bacterial and fungal pulmonary infection. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2012; 18: 228–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Anderson ST, Kaforou M, Brent AJ, et al. , and the ILULU Consortium, and the KIDS TB Study Group. Diagnosis of childhood tuberculosis and host RNA expression in Africa. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1712–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Berry MP, Graham CM, McNab FW, et al. An interferon-inducible neutrophil-driven blood transcriptional signature in human tuberculosis. Nature 2010; 466:973–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Steingart KR, Flores LL, Dendukuri N, et al. Commercial serological tests for the diagnosis of active pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2011; 8: e1001062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Flores LL, Steingart KR, Dendukuri N, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of antigen detection tests for the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2011; 18:1616–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kruk ME, Schwalbe NR, Aguiar CA. Timing of default from tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 2008; 13: 703–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Steffen R, Menzies D, Oxlade O, et al. Patients’ costs and cost-effectiveness of tuberculosis treatment in DOTS and non- DOTS facilities in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS One 2010; 5: e14014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Frieden TR, Sbarbaro JA. Promoting adherence to treatment for tuberculosis: the importance of direct observation. Bull World Health Organ 2007; 85: 407–09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pasipanodya JG, Gumbo T. A meta-analysis of self-administered vs directly observed therapy effect on microbiologic failure, relapse, and acquired drug resistance in tuberculosis patients. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57: 21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.WHO. THE STOP TB STRATEGY, Building on and enhancing DOTS to meet the TB-related Millennium Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2006/WHO_HTM_STB_2006.368_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed July 1, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mac Kenzie WR, Heilig CM, Bozeman L, et al. Geographic differences in time to culture conversion in liquid media: tuberculosis Trials Consortium study 28. Culture conversion is delayed in Africa. PLoS One 2011; 6: e18358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Weiner M, Peloquin C, Burman W, et al. Effects of tuberculosis, race, and human gene SLCO1B1 polymorphisms on rifampin concentrations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54:4192–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chigutsa E, Visser ME, Swart EC, et al. The SLCO1B1 rs4149032 polymorphism is highly prevalent in South Africans and is associated with reduced rifampin concentrations: dosing implications. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55:4122–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Saukkonen JJ, Cohn DL, Jasmer RM, et al. , and the ATS (American Thoracic Society) Hepatotoxicity of Antituberculosis Therapy Subcommittee. An official ATS statement: hepatotoxicity of antituberculosis therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 174: 935–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sharma SK, Singla R, Sarda P, et al. Safety of 3 different reintroduction regimens of antituberculosis drugs after development of antituberculosis treatment-induced hepatotoxicity. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 50: 833–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Prasad K, Singh MB. Corticosteroids for managing tuberculous meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; 1: CD002244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Critchley JA, Young F, Orton L, Garner P. Corticosteroids for prevention of mortality in people with tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13: 223–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mayosi BM, Ntsekhe M, Bosch J, et al. , and the IMPI Trial Investigators. Prednisolone and Mycobacterium indicus pranii in tuberculous pericarditis. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:1121–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Crampin AC, Mwaungulu JN, Mwaungulu FD, et al. Recurrent TB: relapse or reinfection? The effect of HIV in a general population cohort in Malawi. AIDS 2010; 24: 417–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.McIlleron H, Meintjes G, Burman WJ, Maartens G. Complications of antiretroviral therapy in patients with tuberculosis: drug interactions, toxicity, and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. J Infect Dis 2007; 196 (suppl 1): S63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.CDC. Tuberculosis National Center for HIV/AIDS VH, STD, and TB Prevention, Division of tuberculosis Elimination, Managing Drug Interactions in the Treatment of HIV-Related tuberculosis National, 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/guidelines/tb_hiv_drugs/pdf/tbhiv.pdf (accessed July 1, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 99.Müller M, Wandel S, Colebunders R, Attia S, Furrer H, Egger M, and the IeDEA Southern and Central Africa. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in patients starting antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10: 251–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Uthman OA, Okwundu C, Gbenga K, et al. Optimal timing of antiretroviral therapy initiation for HIV-infected adults with newly diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163: 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V, Johnson V, Brewer GJ. Diagnosis and characterization of presymptomatic patients with Wilson’s disease and the use of molecular genetics to aid in the diagnosis. J Lab Clin Med 1991; 118: 458–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tadokera R, Meintjes G, Skolimowska KH, et al. Hypercytokinaemia accompanies HIV-tuberculosis immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Eur Respir J 2011; 37:1248–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Andrade BB, Singh A, Narendran G, et al. Mycobacterial antigen driven activation of CD14++CD16- monocytes is a predictor of tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. PLoS Pathog 2014; 10: e1004433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Barber DL, Andrade BB, Sereti I, Sher A. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: the trouble with immunity when you had none. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012; 10: 150–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Meintjes G, Wilkinson RJ, Morroni C, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of prednisone for paradoxical tuberculosis- associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. AIDS 2010; 24: 2381–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.American Thoracic Society, CDC, and Infectious Diseases Society of America . Treatment of tuberculosis. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mitchison DA, Nunn AJ. Influence of initial drug resistance on the response to short-course chemotherapy of pulmonary tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986;133:423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hong Kong Chest Service/British Medical Research Council. Five-year follow-up of a controlled trial of five 6-month regimens of chemotherapy for pulmonary tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987; 136:1339–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.WHO. WHO updated references on management of drug-resistant tuberculosis: guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis—2011 update. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lange C, Abubakar I, Alffenaar JW, et al. Management of patients with multidrugresistant/extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in Europe: a TBNET consensus statement. Lausanne: ERS Publications, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sotgiu G, Centis R, D’Ambrosio L, et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of linezolid containing regimens in treating MDR-TB and XDR-TB: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2012; 40:1430–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chang KC, Yew WW, Tam CM, Leung CC. WHO group 5 drugs and difficult multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review with cohort analysis and meta-analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 4097–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.WHO. The use of bedaquiline in the treatment of multidrug- resistant tuberculosis: interim policy guidance Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]