Abstract

The 24-h movement guidelines for children and adolescents comprise recommendations for adequate sleep, moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and sedentary behaviour (SB). However, whether adolescents who meet these 24-h movement guidelines may be less likely to have high blood pressure (HBP) has not been established. The present study assessed the association between meeting 24-h movement guidelines and HBP in a school-based sample of 996 adolescents between 10–17 years (13.2 ± 2.4 years, 55.4% of girls). Blood pressure was measured using a digital oscillometric device, while sleep, MVPA and SB were measured using the Baecke questionnaire. The association between the 24-h movement guidelines and HBP was performed using binary logistic regression adjusted for sex, age, socioeconomic status, and body mass index. It was observed that less than 1% of the sample meet the three 24-h movement guidelines. The prevalence of HBP was lower in adolescents who meet all three movement 24-h guidelines (11.1%) compared to those who did not meet any guidelines (27.2%). Individual 24-h movement guidelines analysis showed that adolescents with adequate sleep were 35% less likely to have HBP (OR = 0.65; 95% CI 0.46–0.91). Meeting sleep guidelines combined with meeting MVPA (OR = 0.69; 95% CI 0.50–0.95) or SB (OR = 0.67; 95% CI 0.48–0.94) was inversely associated with HBP. Adolescents who meet two or three 24-h movement guidelines were respectively 47% (OR = 0.53; 95% CI 0.29–0.98) and 34% (OR = 0.66; 95% CI 0.48–0.91) less likely to have HBP. In adolescents, meeting sleep and 24-h movement guidelines were inversely associated with HBP.

Keywords: Movement guidelines, Physical activity, Sedentary behaviour, Sleep, Cardiovascular parameters

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Hypertension

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are still the leading cause of death worldwide1. One of the main risk factors for cardiovascular diseases is high blood pressure (HBP). Studies have shown that HBP can develop as early as childhood and adolescence2, and behaviours such as sleep, physical activity (PA), and sedentary behaviour (SB) have been associated with HBP in these stages of life3–5.

A recent network meta-analysis of 27 studies involving 15,220 children and adolescents showed that PA was one of the predominant factors for reducing systolic and diastolic BP in children and adolescents6. Another important behaviour related to BP is the amount of sleep. Inadequate sleep may be related to greater sympathetic activity and successively increased BP levels. Jiang et al.7, in a meta-analysis with approximately 21 thousand children and adolescents, observed that young people who slept less were more likely to have HBP. SB has also been linked to BP. Silveira et al., in a systematic review, observed that high SB was associated with HBP8. Aggregating these three lifestyle habits (sufficient PA, low SB, and adequate sleep) has been associated with better cardiovascular profiles, including BP9,10.

To minimise or eliminate the harmful effects of these behaviours, Tremblay et al.11 developed the “Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth”. These guidelines recommend that children and adolescents (5–13 years) and adolescents (14–17 years) sleep daily between 9–11 h and 8–10, respectively. Adolescents are also recommended to engage in moderate to vigorous PA for 60 min daily and not remain in activities that characterise recreational screen-based SB for more than two hours a day11.

Some studies have shown that adhering to the three 24-h movement guidelines could be more effective in decreasing cardiovascular risk factors10–12. However, adherence by adolescents has been low. In a recent meta-analysis of adolescents from 23 countries, only 7.1% of youth meet all three 24-h movement guidelines13. In American adolescents, only 3.1% complied with all the behaviours in the 24-h movement guidelines14 and during the COVID-19 lockdown, López-Gil et al.15 observed similar results (11.7%%). In addition, most studies of this nature have been carried out in developed countries such as Canada, the United States and European countries13,16,17 and some developing countries such as Brazil, where similar findings were observed in the southern region of Brazil15,18.

It is currently unclear whether there is an association between following the Canadian 24-h movement guidelines for children and youth and HBP. Additionally, there are no comprehensive Brazilian guidelines for children and adolescents regarding sleep, PA, and SB. Therefore, the Canadian guidelines were applied to Brazilian adolescents for this study. Finally, it is important to consider possible confounding variables associated with HBP, such as age, sex, socioeconomic status, and body mass index5,19. The study investigated the relationship between meeting the 24-h movement guidelines and HBP in children and adolescents while adjusting for the main confounding variables.

Methods

Sample and study design

This is a cross-sectional study. The sample consisted of 996 participants aged between 10–17 from the school system in the city of Presidente Prudente-SP, located in the southeastern region of Brazil. For this purpose, five public schools were randomly selected, one from each city region and private schools. The inclusion criteria for the present study were considered: (i) being between 10 and 17 years old, (ii) being enrolled in one of the schools participating in the study; (iii) not having practised intense PA 24 h before the assessment; (iv) not having consumed caffeinated beverages within 24 h of the assessment20.

The researchers randomly selected schools, and after the meeting with the school directors and permission to explain the aims of the study to the students. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants and their guardians. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP) under protocol number 21600613.4.0000.5402. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

To calculate the sample size, it was considered a prevalence of outcome of 50%, which is adopted in epidemiological studies with multiple outcomes or unclear prevalence21 (considering that the guidelines are composed of three behaviour recommendations), a tolerable error of 5% and a sample power of 80% were considered, which generated a minimum n of 627 participants. Anticipating possible losses, another 30% were added to the sample, which generated a final sample size of 815 participants. To mitigate possible sample losses, the researchers tried to contact students twice who indicated they wanted to participate in the study but were absent on the evaluation day or forgot the consent form signed by one of their guardians.

Data collection

The present study occurred in 2014 and 2015, and the assessments were conducted in the school units. The researchers carried out all assessments with the students, including the application of questionnaires, anthropometric measurements and BP. The researchers administered the questionnaires (paper survey) to students in the school environment.

Blood pressure

A digital oscillometric device with an adjustable cuff was used to measure the sample's systolic and diastolic BP (Omron brand, model HEM-742), previously validated for Brazilian adolescents22. This digital oscillometric device was evaluated following the recommendations of the British Society of Hypertension23, having reached grad e Awhen tested against the mercury column and obtained good accuracy. Researchers with previous training and experience in this type of assessment carried out the adolescents’ BP measurements. The participants remained at rest for five minutes after they arrived in the evaluation room before the first BP measurement. The second BP measurement was taken two minutes after the first measurement, where adolescents remained in the same resting position. The average of the two BP measurements determined the final value of the systolic and diastolic BP. Systolic and/or diastolic BP values higher than or equal to the 95th percentile according to age and sex were classified as HBP, as well as those with BP levels higher than 120/80 mmHg, for systolic and diastolic BP, respectively, as proposed by the National High Blood Pressure Education Program24.

Physical activity

The PA was evaluated through the questionnaire developed by Baecke et al.25 and validated for Brazilian adolescents26. This instrument evaluates three domains of PA with a specific dimensionless scoring (i., PA at school; ii. at leisure time and commuting; iii. the sports practice outside the school). The PA at school refers to occupational activities (sitting, standing, commuting, carrying loads, sweating and the intensity of the day at school, in relation to the intensity compared to people of the same age in a school environment) being assessed by 5-point Likert scale responses, which not allowed to infer about minutes and intensity, and for this reason, was not considered for MVPA calculation. Otherwise, the PA at leisure time and commuting (walking and cycling for leisure and commuting), as well as the sports practice outside the school (sports activities or physical exercise programs developed during leisure time), are assessed by questions regarding frequency, duration, and intensity of physical activities, which allowed to quantify the MVPA. Minutes of these activities, reported as being at least moderate intensity, were summed, whereas those minutes from vigorous intensity were doubled in value. Those adolescents who meet 60 min or more of MVPA per day were classified as complying with the PA behaviour at the 24-Hour Movement Guidelines.

Sedentary behaviour

SB was evaluated by the number of hours per week the adolescents watched television, used the computer and/or played video games on a typical weekday and on a typical weekend day based on the proposed instrument and validated for adolescents by Hardy et al.27. The number of hours in each screen device per day and a weighted screen time average were calculated by multiplying weekday screen time by five and weekend day screen time by two, dividing the total amount by seven (total days of the week). Those adolescents who had less than two hours of daily screen time were considered to meet the sedentary behaviour guideline. This cut-off point was adopted because it aligns with the criteria recommended by the 24-Hour Movement Guidelines11.

Sleep

Adolescents were asked when they usually go to bed and fall asleep and when they wake up in the morning. The difference in time was considered as the hours slept. The 24-h movement guidelines recommended sleep between 9–11 h/day for children and 8–10 h/day for adolescents, which were considered to classify into meet or not meet this guideline in the sample11.

Covariates

Age, sex, socioeconomic status, and body mass index were considered covariates. Brazilian economic classification criteria28 were used to assess the socioeconomic status. This criterion considers information about the educational level of the patriarch of the family and some consumer goods and rooms at home, providing a socioeconomic score where the higher the value, the higher the socioeconomic condition. Body mass index was calculated (body mass/height2) through objective measurements of height (in meters) and body mass (in kilograms), respectively collected by a wall-fixed stadiometer and digital scale, with participants barefoot and wearing light clothes.

Statistical analysis

Sample characteristics were presented in mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. Adolescents were grouped according to the number of behaviours they meet following the 24-h movement guidelines, and the one-way ANOVA was used to compare the continuous variables between groups, with the posthoc of Bonferroni for detecting group differences. The chi-square test compared the proportions of categorical variables according to meeting 24-h movement guidelines. The association between HBP and 24-h movement guidelines behaviours was analysed by binary logistic regression adjusted for sex, age, socioeconomic status, and body mass index. It was adopted a significance level of p < 0.05 and 95% confidence interval. Analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package version 25.0.

Results

The present study assessed a final sample of 996 adolescents, with an average age of 13.2 ± 2.4 years, 55.4% of whom were girls. Table 1 presents the sample`s characteristics according to the 24-h movement guidelines. The mean age and DBP were higher in adolescents who did not meet any of the 24-h guidelines compared to those who meet two 24-h guidelines components. In addition, adolescents who did not meet any 24-h guidelines also presented less sleep time, lower MVPA, and more time in SB.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics according to the number of behaviours in the 24-h movement guidelines (n = 996).

| No guideline met (n = 453) | Meet 1 guideline (n = 440) | Meet 2 guidelines (n = 94) | Meet 3 guidelines (n = 9) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 13.40 (2.50)b | 13.01 (2.23) | 12.67 (2.09) | 13.30 (2.47) | 0.014 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 20.43 (4.04) | 20.37 (4.55) | 19.77 (3.90) | 18.85 (3.15) | 0.396 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 116.63 (13.44) | 115.93 (13.00) | 112.81 (11.86) | 114.71 (14.95) | 0.092 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 67.85 (9.32)b | 67.09 (9.53) | 64.77 (8.40) | 65.29 (8.48) | 0.035 |

| Sleep (hours/day) | 6.69 (1.40)a,b,c | 8.02 (1.57)b,c,M | 8.93 (1.14) | 9.11 (1.05) | ≤ 0.001 |

| MVPA (min/day) | 10.77 (23.02)a,b,c | 27.97 (44.03)b,c,M | 42.30 (45.07) | 65.71 (71.29) | ≤ 0.001 |

| Sedentary behaviour (hours/day) | 13.23 (5.43)a,b,c | 11.56 (6.11)b,c | 7.97 (6.87)M | 2.78 (1.17) | ≤ 0.001 |

SD standar deviation, MVPA moderate-to-vigorous physical activity.

a = difference against meet one guideline; b = difference against meet two guidelines; c = difference against meet three guidelines; M = significantly higher mean value in males than females.

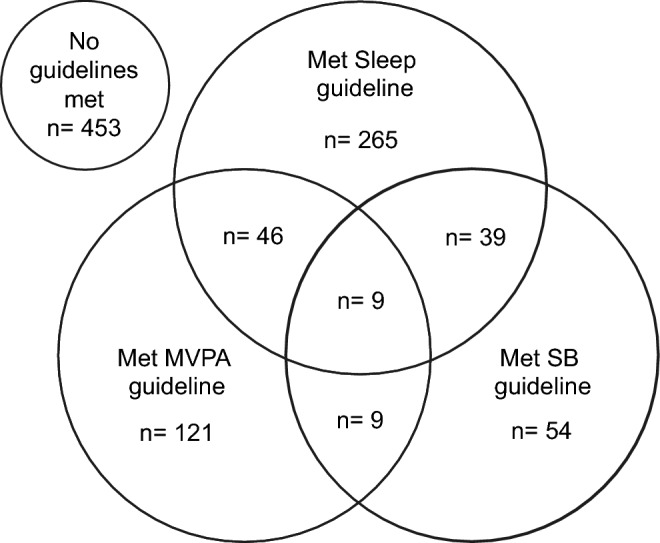

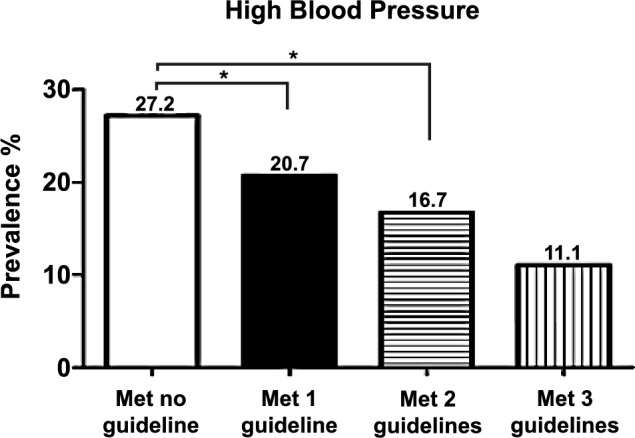

The Venn diagram presented the sample's prevalence of meeting 24-h movement guidelines (Fig. 1). The prevance of HBP according to the 24-h movement guidelines was presented in Fig. 2. The highest prevalence of HBP was observed in adolescents who did not meet any of the 24- hour movement guidelines.

Figure 1.

Venn diagram of meeting 24-h movement guidelines in adolescents (n = 996). MVPA moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, SB sedentary behaviour.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of high blood pressure according to 24-h guidelines. *Statistical difference in proportions at p < 0.05 level.

Table 2 presents the associations of 24-h guidelines and HBP, separately or in combination. About 36% (n = 359) presented an adequate sleep duration, while 18.6% (n = 185) of adolescents practiced at least 60 min of MVPA daily. Lastly, 11.1% (n = 111) spent less than two hours in sedentary behaviour.

Table 2.

Association between 24-h movement guidelines and high blood pressure in adolescents (n = 996).

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual guidelines* | |||

| Sleep | 0.65 | 0.46–0.91 | 0.011 |

| PA | 0.73 | 0.48–1.11 | 0.137 |

| SB | 0.86 | 0.50–1.47 | 0.579 |

| Specific combinations* | |||

| Sleep + PA | 0.69 | 0.50–0.95 | 0.021 |

| Sleep + SB | 0.67 | 0.48–0.94 | 0.020 |

| PA + SB | 0.70 | 0.49–1.01 | 0.058 |

| Guidelines adherence | |||

| None | 1.00 | Reference | – |

| Meet 1 guideline | 0.47 | 0.05–4.03 | 0.490 |

| Meet 2 guidelines | 0.53 | 0.29–0.98 | 0.041 |

| Meet 3 guidelines | 0.66 | 0.48–0.91 | 0.024 |

Adjusted by sex, age, socioeconomic level, and body mass index.

PA physical activity, SB sedentary behavior, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval.

*Not meeting the specific combinatios was defined as reference category.

Considering the combination of two 24-h guidelines components, only 5% reported an adequate sleep duration and PA (n = 55), while 4.8% reported adequate sleep duration and SB (n = 48) and 1.8% (n = 18) adequate PA and SB. Considering all 24-h guidelines components, only 1% (n = 9) of the sample meet the guideline. In addition, approximately 10% of the sample meet at least two 24-h guidelines components, 44% meet only one component and 45% did not meet any guidelines components. In the individual guideline analysis, adolescents who reported the recommended sleep presented 35% lower chances to have HBP. When considered the combination of two 24-h guidelines components, 9–11 h of sleep and at to practice least 60 min of PA daily was related to 31% lower chances of having HBP, while meeting the recommended sleep and having less than two hours in SB was related to 33% lower chance of having HBP. Lastly, in the clustered analysis, meeting at least two 24-h guidelines components were associated with 47% lower chance of having HBP. In contrast, adolescents who fully meet the 24-h guideline presented 34% less likely to have HBP.

Discussion

The present study observed a low prevalence of adolescents who meet the 24-h movement guidelines. When analysing the 24-h movement guidelines separately, those participants who meet sleep recommendations were less likely to have HBP. When considering the combinations of sleep with MVPA or SB recommendations, a significant association with lower HBP was observed. In clustered behaviour analysis, adolescents who meet at least two or all the three 24-h movement guidelines were less likely to have HBP.

The low prevalence of adolescents who meet the 24-h movement guidelines in the present study corroborates with previous findings. Roman-Vinas et al.16 demonstrated that only 7.2% of the children of twelve countries analysed in their study meet the 24-h movement guidelines. Such results are similar to those shown by Tapia-Serrano et al.13 in a meta-analysis involving more than 385.000 children and adolescents (3–18 years old) from 23 countries. One possible reason for the low prevalence may be that this population has difficulty meeting recommended levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity and SB separately29. Another issue to consider is that adolescents tend to sleep late and less than necessary at night30, reflecting the difficulty in meeting sleep recommendations. Different initiatives such as those promoted by the global alliance through the report card, which monitors different lifestyle habits in children and adolescents in different parts of the world, have reported the difficulty young people have in achieving sufficient levels of PA and sleep, as well as decreasing the SB31–34. Such reasons may be linked to the family environment or structure, for example.

Regarding sleeping time, the odds of having HBP were 35% lower when the sleep guideline was meet in the present study. A study conducted by Gangwisch et al. demonstrated that the reduction in sleep has been associated with an increase in blood pressure35, and this association may be related to several mechanisms, including increased sympathetic activity, inflammation, oxidative stress and weight gain that the reduction in sleep can promote36,37. Therefore, meeting the sleep guideline seems to protect the body from these harmful effects and minimise the chance of BP elevation. In addition, one of the possible reasons for these findings is that during sleep, both heart rate and blood pressure are reduced and regeneration of the cardiovascular system occurs, it is in these phases that hormones that control circulation are released38.

Considering PA, it has been observed that the PA was inversely associated with blood pressure values in adolescents39,40. One of the possible mechanisms is that PA contributes to the release of nitric oxide and consequently improves the elasticity of blood vessels41. Another factor is that MVPA was associated with parasympathetic activity42, which can contribute to blood pressure control. When considering the cluster of meeting the 24-h movement guidelines, participants who meet two or three guidelines were less likely to have HBP. Our findings are supported by those from Carson et al.10, who reported that those participants from a sample of 4157 children and adolescents aged 6–17 who meet more 24-h movement guidelines had better blood pressure values. On the other hand, previous findings from Katzmarzyk and Staiano43 in a sample of 357 African American aged between 5–18 years showed no association of the number of guidelines met with blood pressure levels, although significant associations with obesity, triglycerides and glucose were reported. Saunders et al.44 in a systematic review considering the combination of PA, SB and sleep in children and adolescents aged 5 to 17 years, showed that those young people who had high PA/ high amount of sleep and low SB had better cardiometabolic health when compared to young people who did not have one or more of these components. In addition, the combination of meeting sleep guidelines and MVPA or SB was associated with lower HBP in the present study.

Although meeting SB guidelines isolated was not associated with HBP in the present study, Christofaro et al.5 previously observed that high levels of SB was associated with HBP in Brazilian adolescents. Ullrich-French et al.45 also reported that American adolescents who had more than two hours a day of SB were more likely to have HBP. Considering the physiology of a sedentary lifestyle, prolonged sedentary time was associated with endothelial dysfunction46 and contributed to the atherosclerotic process47. McManus et al.48 observed that even at younger ages, more than three hours of sitting per day was associated with reduced vascular function among girls aged 7–10 years.

As the main limitations of the present study, we highlight the cross-sectional design, which makes it impossible to infer cause and effect and may be susceptible to reverse causality, besides the fact that questionnaires assessed PA, SB and sleep. Furthermore, the dimensionless score of the Baecke questionnaire for the school activities domain did not allow it to be included in the MVPA calculation, being susceptible to underestimating values. Another limitation is that the lifestyle habits of the 24-h movement guidelines (which were not considered in the adjustment of statistical analyses) could be mediators between them. For example, sleep contributes to increased PA and reduced SB and influences HBP, but other potential mediators like pubertal status and diet quality were not assessed. Finally, BP was measured on a single occasion, which may be susceptible to fluctuations, making it impossible to detect arterial hypertension. Otherwise, the significant number of participants, adjustment of analysis for confounding factors, and the randomised sample recruitment aimed to minimise the sampling bias were considered strengths of the study.

In conclusion, although a few participants meet the 24-h movement guidelines, meeting sleep recommendations was the only behaviour associated with HBP when analysing the 24-h guidelines separately. Meeting sleep guidelines combined with MVPA or SB guidelines was associated with a lower chance of having HBP. Meeting at least two or all three 24-h movement guidelines was associated with lower HBP. Strategies aiming to meet sleep recommendations, increase MVPA, and reduce SB should be encouraged for facing HBP in adolescents.

Author contributions

DGDC is the guarantor of the article. DGDC, JM, WRT and JB designed the study. DGDC, LCMV and WRT were responsible for data curation. GF, GGC, DRS and JB critically revised the manuscript. DGDC, GF and JB provided study resources. All authors made substantial contributions and approved the final version of manuscript.

Data availability

The manuscript data is available by the corresponding author through reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Roth, G. A. et al. GBD-NHLBI-JACC global burden of cardiovascular diseases writing group. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.76(25), 2982–3021. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gartlehner, G. et al. Screening for hypertension in children and adolescents: Updated evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA324(18), 1884–1895. 10.1001/jama.2020.11119 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuan, Y. et al. Poor sleep quality is associated with new-onset hypertension in a diverse young and middle-aged population. Sleep Med.88, 189–196. 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.10.021 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu, H. et al. Effect of comprehensive interventions including nutrition education and physical activity on high blood pressure among children: Evidence from school-based cluster randomized control trial in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health17(23), 8944. 10.3390/ijerph17238944 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christofaro, D. G. et al. High blood pressure and sedentary behaviour in adolescents are associated even after controlling for confounding factors. Blood Press.24(5), 317–323. 10.3109/08037051.2015.1070475 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassan, M. A., Zhou, W., Ye, M., He, H. & Gao, Z. The effectiveness of physical activity interventions on blood pressure in children and adolescents: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Sport Health Sci.S2095–2546(24), 00004–00008. 10.1016/j.jshs.2024.01.004 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang, W., Hu, C., Li, F., Hua, X. & Zhang, X. Association between sleep duration and high blood pressure in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Hum. Biol.45(6–8), 457–462. 10.1080/03014460.2018.1535661 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silveira, L. S., Inoue, D. S., Rodrigues da Silva, J. M., Cayres, S. U. & Christofaro, D. G. D. High blood pressure combined with sedentary behavior in young people: A systematic review. Curr. Hypertens. Rev.12(3), 215–221. 10.2174/1573402112666161230120855 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leppänen, M. H. et al. Longitudinal and cross-sectional associations of adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines with cardiometabolic risk. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports32(1), 255–266. 10.1111/sms.14081 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carson, V., Chaput, J. P., Janssen, I. & Tremblay, M. S. Health associations with meeting new 24-hour movement guidelines for Canadian children and youth. Prev. Med.95, 7–13. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.12.005 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tremblay, M. S. et al. Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth: An integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab.416, 311–327. 10.1139/apnm-2016-0151 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu, X., Healy, S., Haegele, J. A. & Patterson, F. Twenty-four-hour movement guidelines and body weight in youth. J. Pediatr.218, 204–209 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tapia-Serrano, M. A. et al. Prevalence of meeting 24-hour movement guidelines from pre-school to adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis including 387,437 participants and 23 countries. J. Sport Health Sci.11(4), 427–437. 10.1016/j.jshs.2022.01.005 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu, B. P., Jia, C. X. & Li, S. X. The association of soft drink consumption and the 24-hour movement guidelines with suicidality among adolescents of the United States. Nutrients14(9), 1870. 10.3390/nu14091870 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.López-Gil, J. F., Tremblay, M. S. & Brazo-Sayavera, J. Changes in healthy behaviors and meeting 24-h movement guidelines in Spanish and Brazilian preschoolers, children and adolescents during the COVID-19 lockdown. Children (Basel)8(2), 83. 10.3390/children8020083 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roman-Viñas, B. et al. Proportion of children meeting recommendations for 24-hour movement guidelines and associations with adiposity in a 12-country study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys Act.13(1), 123. 10.1186/s12966-016-0449-8 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts, K. C. et al. Meeting the canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth. Health Rep.28(10), 3–7 (2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.da Costa, B. G. G., Chaput, J. P., Lopes, M. V. V., Malheiros, L. E. A. & Silva, K. S. D. Associations between sociodemographic, dietary, and substance use factors with self-reported 24-hour movement behaviors in a sample of Brazilian adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health18(5), 2527. 10.3390/ijerph18052527 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sosso, F. E. & Khoury, T. Socioeconomic status and sleep disturbances among pediatric population: A continental systematic review of empirical research. Sleep Sci.14(3), 245–256. 10.5935/1984-0063.20200082 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zanuto, E. F. et al. Is physical activity associated with resting heart rate in boys and girls? A representative study controlled for confounders. J. Pediatr.96(2), 247–254. 10.1016/j.jped.2018.10.007 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agranonik, M. & Hirakata, V. N. Sample size calculation: Proportions. Rev. HCPA31(3), 382–388 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christofaro, D. G. et al. Validation of the Omron HEM 742 blood pressure monitoring device in adolescents. Arq. Bras. Cardiol.92(1), 10–15. 10.1590/s0066-782x2009000100003 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Brien, E. et al. The british hypertension society protocol for the evaluation of automated and semi-automated blood pressure measuring devices with special reference to ambulatory systems. J. Hypertens.8(7), 607–619 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics114(2), 555–576 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baecke, J. A., Burema, J. & Frijters, J. E. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr.36(5), 936–942. 10.1093/ajcn/36.5.936 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guedes, D. P., Lopes, C. C., Guedes, J. E. R. P. & Stanganelli, L. C. Reprodutibilidade e validade do questionário Baecke para avaliação da atividade física habitual em adolescentes. Rev. Port. Cien. Desp.6(3), 265–274 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hardy, L. L., Booth, M. L. & Okely, A. D. The reliability of the adolescent sedentary activity questionnaire (ASAQ). Prev. Med.45(1), 71–74 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brazilian Association of Research Companies. Brazilian Criteria for Economic Classification. www.abep.org/Servicos/Download.aspx?id=02. Accessed 01 August 2022.

- 29.Christofaro, D. G., De Andrade, S. M., Mesas, A. E., Fernandes, R. A. & Farias Júnior, J. C. Higher screen time is associated with overweight, poor dietary habits and physical inactivity in Brazilian adolescents, mainly among girls. Eur. J. Sport Sci.16(4), 498–506 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keyes, K. M., Maslowsky, J., Hamilton, A. & Schulenberg, J. The great sleep recession: Changes in sleep duration among US adolescents, 1991–2012. Pediatrics135(3), 460–468. 10.1542/peds.2014-2707 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bakalár, P. et al. First report card on physical activity for children and adolescents in Slovakia: A comprehensive analysis, international comparison, and identification of surveillance gaps. Arch. Pub. Health82(1), 16. 10.1186/s13690-024-01241-4 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mendoza-Muñoz, M. et al. A regional report card on physical activity in children and adolescents: The case of extremadura (Spain) in the global matrix 4.0. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit.22(1), 23–30. 10.1016/j.jesf.2023.10.005 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, E. Y. et al. Report card grades on physical activity for children and adolescents from 18 Asian countries: Patterns, trends, gaps, and future recommendations. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit.21(1), 34–44. 10.1016/j.jesf.2022.10.008 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silva, D. A. S. et al. Results from Brazil’s 2022 report card on physical activity for children and adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health19(16), 10256. 10.3390/ijerph191610256 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gangwisch, J. E. A review of evidence for the link between sleep duration and hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens.27(10), 1235–1242. 10.1093/ajh/hpu071 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Méier-Ewert, H. K. et al. Effect of sleep loss on C-reative protein, an inflammatory marker of cardiovascular risk. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.43(4), 678–683. 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.050 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller, M. A. & Cappuccio, F. P. Biomarkers of cardiovascular risk in sleepdeprived people. J. Hum. Hypertens.27(10), 583–588. 10.1038/jhh.2013.27 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gordan, R., Gwathmey, J. K. & Xie, L. H. Autonomic and endocrine control of cardiovascular function. World J. Cardiol.7(4), 204–214. 10.4330/wjc.v7.i4.204 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wellman, R. J. et al. Intensity and frequency of physical activity and high blood pressure in adolescents: A longitudinal study. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich)22(2), 283–290. 10.1111/jch.13806 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christofaro, D. G. et al. Physical activity is inversely associated with high blood pressure independently of overweight in Brazilian adolescents. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports23(3), 317–322. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01382 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zanesco, A. & Antunes, E. Effects of exercise training on the cardiovascular system: Pharmacological approaches. Pharmacol. Ther.114(3), 307–317. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.010 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christofaro, D. G. D. et al. Association of cardiac autonomic modulation with different intensities of physical activity in a small Brazilian inner city: A gender analysis. Eur. J. Sport Sci.10.1080/17461391.2022.2044913 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katzmarzyk, P. T. & Staiano, A. E. Relationship between meeting 24-hour movement guidelines and cardiometabolic risk factors in children. J. Phys. Act. Health14(10), 779–784. 10.1123/jpah.2017-0090 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saunders, T. J. et al. Combinations of physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep: Relationships with health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab.41, S283–S293. 10.1139/apnm-2015-0626 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ullrich-French, S. C., Power, T. G., Daratha, K. B., Bindler, R. C. & Steele, M. M. Examination of adolescents’ screen time and physical fitness as independent correlates of weight status and blood pressure. J. Sports Sci.28(11), 1189–1196. 10.1080/02640414.2010.487070 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Padilla, J. & Fadel, P. J. Prolonged sitting leg vasculopathy: Contributing factors and clinical implications. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol.313, H722–H728 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ross, R. Atherosclerosis—An inflammatory disease. N. Engl. J. Med.340, 115–126 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McManus, A. M. et al. Impact of prolonged sitting on vascular function in young girls. Exp. Physiol.100(11), 1379–1387. 10.1113/EP085355 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The manuscript data is available by the corresponding author through reasonable request.