Abstract

School eye health (SEH) has been on the global agenda for many years, and there is mounting evidence available to support that school-based visual screenings are one of the most effective and cost-efficient interventions to reach children over five years old. A scoping review was conducted in MEDLINE, Web of Science, PubMed, and CINHAL between February and June 2023 to identify current priorities in recent literature on school eye health in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Selection of relevant publications was performed with Covidence, and the main findings were classified according to the WHO Health Promoting Schools framework (HPS). A total of 95 articles were included: cross-sectional studies (n = 55), randomised controlled trials (n = 7), qualitative research (n = 7) and others. Results demonstrate that multi-level action is required to implement sustainable and integrated school eye health programmes in low and middle-income countries. The main priorities identified in this review are: standardised and rigorous protocols; cost-effective workforce; provision of suitable spectacles; compliance to spectacle wear; efficient health promotion interventions; parents and community engagement; integration of programmes in school health; inter-sectoral, government-owned programmes with long-term financing schemes. Even though many challenges remain, the continuous production of quality data such as the ones presented in this review will help governments and other stakeholders to build evidence-based, comprehensive, integrated, and context-adapted programmes and deliver quality eye care services to children all over the world.

Subject terms: Public health, Health services

Abstract

学校眼健康 (SEH) 已列入全球议程多年, 越来越多的证据支持, 在学校中进行的的视力筛查是五岁以上儿童最有效和最具成本效益的干预措施之一。从2023年2月至6月, 我们在MEDLINE, Web of Science, PubMed和CINHAL上进行了搜素, 确定中低收入国家 (LMICs) 学校眼健康的最新文献中的推荐的优先事件。使用Covidence进行相关文献检索, 并根据世界卫生组织促进健康学校框架 (HPS) 进行分类。总共纳入95篇文章: 横断面研究 (n = 55) 、随机对照试验 (n = 7) 、定性研究 (n = 7) 和其他。研究结果表明, 需要采取多层次的行动, 在中低收入国家实施可持续和综合的学校眼健康方案。本分析中确定的主要优先事件包括: 标准化和严格的程序;性价比高的劳动力;提供合适的眼镜;配镜依从性;有效的健康促进干预;家长和社区的参与;整合学校医疗保健;由政府主导的具有长期融资计划的跨部门项目。尽管仍有许多挑战, 但持续产生高质量的数据, 如本次调查中提供的数据, 将有助于政府和其他利益攸关方建立循证、全面、综合和适应环境的方案, 并为世界各地的儿童提供高质量的眼部护理服务。

Introduction

Access to quality eye care is essential to achieve the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals [1]. Nevertheless, 2.2 billion people suffer from visual impairment (VI), with 90% of them living in low and middle-income countries (LIMCs) [1]. Vision loss can have a significant impact on education outcomes and life opportunities, but even so, approximately 70.2 million children under 14 years old are visually impaired or blind, mostly from uncorrected refractive errors [1]. Specific data on school-going children is limited but global estimates evaluate that 448 million children present a significant refractive error [2].

One of the most effective and cost-efficient interventions to deliver eye care to children is through school-based eye health programmes (SEHP) [1] This model is traditionally driven by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and consists of outreach teams that visit schools, screen for children presenting reduced visual acuity (VA) and provide spectacles or referrals for advanced or specialist clinical care. While most agree that these interventions are important, there is no consensus on the optimal selection of tests or personnel to conduct screenings, and practices still vary widely, especially in limited resources settings [3, 4]. Since 2016, many guidelines have been published to guide governments and organizations in planning, implementing, and evaluating sustainable school-based initiatives such as the International Agency for Prevention of Blindness School Eye Health (SEH) guidelines for LMICs [5]. However, the global context has changed since the publication of these guidelines, namely with the COVID-19 pandemic but also with recent developments in global eye health such as the official integration of eye health in the UN’s universal health coverage objectives.

Therefore, this scoping review aims to identify new evidence published relative to SEH initiatives and identify topics to prioritise in future SEH programmes for LMICs.

Methodology

We developed a scoping review protocol in accordance with JBI methodology for scoping reviews [6] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [7]. The protocol was not published a priori. The research question was: What are the best practices in school eye health initiatives for children from low-middle-income countries in recent publications since the release of IAPB’s guideline in 2016? With the assistance of a biomedical research librarian from Université de Montréal, we developed a search strategy based on the main search terms: school setting, eye health, school-aged children, and LMICs. Complete search strategy in presented in Appendix 1. The search was carried in four online databases, respectively MEDLINE®, Web of Science™, PubMed®, and CINHAL between February and June 2023. The main concept of the search, school-eye health initiatives, has been described as follows by Burton et al. [1]: ‘comprehensive school-based programmes that include screening approaches to identify children with vision impairment, spectacle provision, health education, promotion, and support inclusive education for children with vision impairment’. All search results were imported in Covidence software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) and duplicates were automatically removed. References were included when conducted in LMICs based on World Bank’s classification for the year 2023 [8], in school settings, with a population of schoolchildren aged 5–17years old, and published in English since 2016. A public health optometrist (AH) performed screening of title, abstract, and full text, with the support of an optometry professor (BT) when there was uncertainty on eligibility. We included only primary studies, but manual search of references in relevant systematic reviews and meta-analysis provided additional records. Editorials, advanced clinical studies, epidemiological studies, and those conducted in disability schools were excluded. Studies on refractive errors were included if associated with preventable risk factors.

Based on the main topics emerging from the initial search, specific research questions were formulated: What are the new topics that can be found in recent literature on SEH? What national, local, and school-levels policies facilitate integration and scalability of SEH programmes? What are the best practices to promote SEH in school settings that lead to better compliance? Which protocols, techniques, and technologies result in better outcomes?

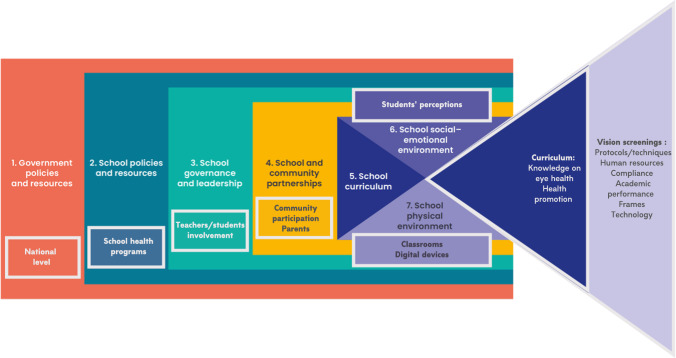

We therefore extracted the main outcomes of all the selected studies, but also screening protocols details such as visual acuity cut-off, refractive error definitions, and charts used. We subsequently sorted results according to the Health Promoting Schools framework (HPS) [9]. This framework, first introduced by the WHO in 1995 and updated in 2021, ‘provides a resource to education systems to foster health and well-being through stronger governance’ [9]. It is an ecological model that proposes integration of school health services in a multi-level approach. The eight global standards of HPS defined by the WHO were adapted to school eye health with themes from literature, as shown in Fig. 1. These concepts are very well aligned with the integrated approach suggest by the WHO and IAPB in the current guidelines for school eye health programmes [5, 10]. Indeed, school-based vision screening are direct health services but all the other components are required to ensure the delivery of sustainable, comprehensive, and effective school eye health programmes.

Fig. 1. WHO’s Health-Promoting Schools framework adapted to school-eye health*.

This figure illustrates the eight components of HPS for integrated school-based eye health services: 1—government policies : national scaling, sustainability; 2—school policies : integration in school health programmes; 3—school governance and leadership: school directions, teachers and students’ leadership; 4—school and community partnerships: community involvement; 5—school curriculum : health promotion, myopia prevention; 6—school social–emotional environment : students’ and parents’ perceptions; 7—school physical environment: classrooms, digital device used; and 8—school health services: screening protocols and techniques, outcomes (spectacles provision, compliance, academic performance and new technologies). *Adapted from World Health Organization. Health Promoting Schools (2021) [9].

Results

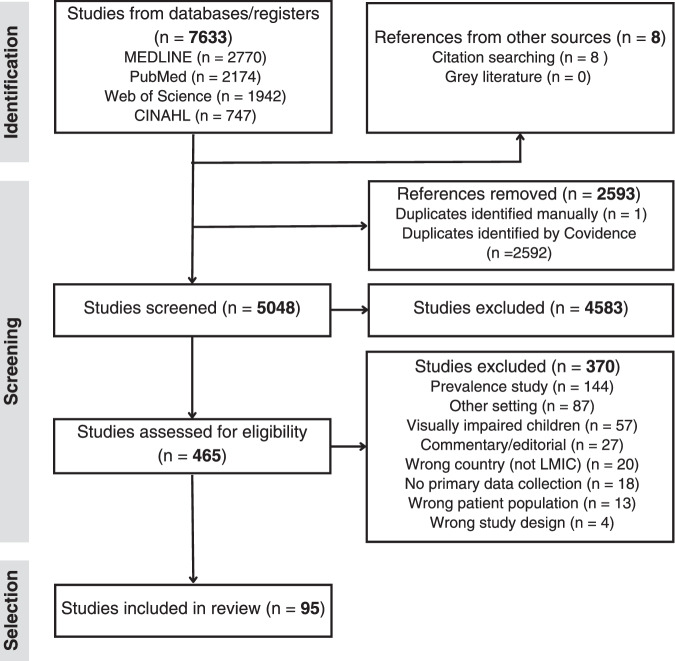

A total of 7633 studies were retrieved from database searches and eight additional records were added through footnote chasing, as presented in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 2). After the selection process, 95 publications were included, sorted by main theme, and summarized in Table 1. Almost half of the articles were from India (n = 44; 46.3%), others being mostly from Africa (n = 36.5; 38.4%) and Asia (n = 14.5; 15.3%). Most of the publications were cross-sectional studies (n = 55), with a few randomised experimental studies (n = 7), qualitative research (n = 7), economic evaluation (n = 5), and other designs (n = 21).

Fig. 2. PRISMA chart.

PRISMA chart for school-eye health scoping review.

Table 1.

Characteristics of selected studies.

| HPS theme | Main theme | Main author | Country | Study design | Aim of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School-based screenings | Protocols and techniques | Aina [14] | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | to compare focometer and autorefractor in the measurement of refractive errors among students in an underserved community of sub-Saharan Africa |

| Chottopadhyay [13] | India | Cross-sectional study | to evaluate the referral rate when only distance visual acuity was used as the screening tool versus using retinoscopy | ||

| Gopalakrishnan [17] | India | Non-randomised experimental study | to investigate the agreement between cycloplegic and non-cycloplegic autorefraction with an open-field autorefractor in a school vision screening setup, and to define a threshold for myopia that agrees with the standard cycloplegic refraction threshold | ||

| Ilechie [15] | Ghana | Cross-sectional study | to evaluate the ability of non-cycloplegic autorefraction and non-cycloplegic retinoscopy to detect refractive errors in school-aged African children and quantify differences between non-cycloplegic and cycloplegic refraction measures | ||

| Khurana [16] | India | Cross-sectional study | to compare the accuracy of non-cycloplegic refraction done by an optometrist in school camp with that done in eye clinic in children aged 6–16 years and analyze the factors affecting it. | ||

| Mathenge [18] | Rwanda | Cross-sectional study | to explore the use of the World Health Organization (WHO) primary eye care screening protocol | ||

| Panda [11] | India | Cross-sectional study | to explore the possibility of vitamin A deficiency (VAD) detection through School Sight Programme(SSP) in a tribal district of Odisha, India | ||

| Saravanan [22] | India | Economic evaluation | to analyse the cost of a comprehensive school eye screening model while utilising optometrists and optometry students | ||

| Sil [21] | India | Implementation evaluation | to describe in detail the process and protocol for implementation of the REACH programme across five states in India and its progress to date, and to raise awareness of this novel approach to child vision screening with scope for wider implementation; progress to date and compliance data are not reported here | ||

| Technology | Ilechie [26] | Ghana | Prospective study | to assess compliance with wearing of self-adjustable spectacles and factors associated with compliance in pre-teen schoolchildren at 6 months after spectacles were dispensed | |

| Morjaria [33] | India | Randomised controlled trial | to demonstrate if a higher proportion of children with uncorrected refractive errors in the schools allocated to the Peek intervention will wear their spectacles 3–4 months after they are dispensed. | ||

| Murali [29] | India | Randomised controlled trial | to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of photoscreeners in identifying refractive errors making children at risk of amblyopia | ||

| Ocansey [25] | Ghana | Cross-sectional study | to compare the performance of two self-refracting spectacles (SRSs) among children in Ghana | ||

| Prabhu [28] | India | Cross-sectional study | to evaluate the performance of Plusoptix A09 in detecting ametropia, warranted against frequently-used technique of retinoscopy in children attending school and its probability as a screening too | ||

| Reddy [27] | India | Cross-sectional study | to compare the photorefraction system(Welch Allyn Spot™) performance with subjective refraction in school sight programme in one Odisha(India) tribal district. | ||

| Rono [32] | Kenya | Randomised controlled trial | to validate the Peek School eye health system and to assess the effect of this system on the referral rate of children with visual impairment compared with the standard visual screening system currently used in Kenya | ||

| Srivastava [31] | India | Cross-sectional study | to assessthe reliability of smartphone photographs in detecting ocular morbidities in school children andto compare it with traditional vision screening | ||

| Vidhya [30] | India | Prospective RTC study | to evaluate the accuracy of photoscreeners in identifying children at risk for amblyopia and to assess the prevalence of amblyopia in Karnataka, India. | ||

| Workforce | Bechange [45] | Pakistan | Qualitative research | to explore the experiences of teachers and optometrists involved a school-based vision screening programme regarding training, vision screening and referrals and to identify factors impacting on the effectiveness of the programme | |

| Bhattarai [48] | Nepal | Cross-sectional study | to assess the validity of vision screening of school children by trained high school students when compared to optometrist testing as the gold standard | ||

| Dole [47] | India | Cross-sectional study | to assess the efficacy of vision screeners (locally trained community volunteers) as compared to a gold standard (personnel with one‑year training in ophthalmology) | ||

| Kaur [43] | India | Cross-sectional study | to evaluate the effectiveness of introducing teachers as the first-level vision screeners | ||

| Marmamula [44] | India | Cross-sectional study | to compare the agreement and diagnostic accuracy of vision screening conducted by trained community eye-health workers and teachers with reference to vision technicians | ||

| Muralidhar [40] | India | Cross-sectional study | to determine the sensitivity and specificity of vision screening by school teachers among primary school children | ||

| Panda [20] | India | Cross-sectional study | to describe programme planning and effectiveness of multi-stage school eye screening and assess accuracy of teachers in vision screening and detection of other ocular anomalies in Rayagada District School Sight Programme, Odisha, India | ||

| Paudel [39] | Vietnam | Cross-sectional study | to assess validity of teacher-based vision screening and elicit factors associated with accuracy of vision screening in Vietnam. | ||

| Rewri [19] | India | Cross-sectional study | to assess the reliability of school teachers for vision screening of younger school children and to study the pattern of vision problems | ||

| Sabherwal [46] | India | Randomised controlled trial | to compare the sensitivity, specificity and cost of visual acuity screening as performed by all class teachers (ACTs), selected teachers (STs) and vision technicians (VTs) in north Indian schools. | ||

| School-based screenings | Workforce | Shukla [41] | India | Prospective study | to provide a comprehensive picture of school vision screening programme for RE in primary class students including the prevalence of RE, validation of vision screening done by the teachers, and spectacles compliance among the primary school students |

| Tobi [42] | Liberia | Cross-sectional study | to assess the prevalence of refractive errors and accuracy of screening by teachers in Grand Kru County, Liberia | ||

| Outcomes (Academic performance) | Latif [50] | Pakistan | Non-randomised experimental study | to study the impact of refractive corrections on the academic performance of high school children in Lahore | |

| Olatunji [49] | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | to assess the quality of education of the children with URE in Sokoto metropolis, Sokoto State, Nigeria. | ||

| Outcomes (Spectacle wear) | Aghaji [63] | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | to explore spectacle preference in school children in Enugu state, Nigeria | |

| Anwar [53] | Pakistan | Prospective study | to study compliance of spectacles and determine the reasons of noncompliance among school-going children in District Rawalpindi | ||

| Bhandari [60] | Nepal | Cross-sectional study | to determine the compliance of spectacle wear among children undergoing school visual acuity testing with free distribution of eyeglasses and explore the determinants for noncompliance. | ||

| Bhatt [58] | India | Prospective study | to document the actual rate of spectacle wear at the time of examination, assess principle determinants of spectacle wear and reasons for non-compliance among different demographic groups | ||

| Ezinne [71] | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | to determine spectacle utilisation rate and reasons for noncompliance with spectacle wear amongst primary school children | ||

| Gajiwala [55] | India | Cross-sectional study | to know the compliance of wearing spectacles provided during school screening programme and to find out reasons for noncompliance and to get information regarding the types of modifications required in the school eye screening programme to improve the compliance level | ||

| Gupta [52] | India | Prospective study | to assess 1-year compliance to spectacles and its associated factors among schoolchildren in urban Delhi diagnosed as having myopia and provided subsidized spectacles | ||

| Kumar [69] | India | prospective study | to study the compliance of spectacle use in children and to analyse factors determining the compliance of spectacle use in them. | ||

| Morjaria [56] | India | Randomised controlled trial | to determine whether less expensive ready-made -spectacles produce rates of spectacle wear at 3 to 4 months comparable to those of more expensive custom-made spectacles among eligible school-aged children | ||

| Morjaria [54] | India | to investigate predictors of spectacle wear and reasons for non-wear in students randomised to ready-made or custom-made spectacles | |||

| Narayanan [61] | Qualitative research | to understand the perceptions of adolescents and their parents about spectacle compliance of adolescents in Southern India | |||

| Narayanan [24] | India | Qualitative research | to understand the barriers to compliance and strategies to overcome the barriers from the perspectives of the service providers of the school vision‑screening model | ||

| Pawar [51] | India | Prospective study | to study the prevalence and determinants of compliance with spectacle wear among school-age children in South India who were given spectacles free of charge under a school vision screening programme | ||

| Thapa [57] | Nepal | Non-randomised experimental study | to determine whether an intervention visit (solutions of physical barriers from the perspective of students) at 3 months by an ophthalmic team improved compliance with spectacle wear and to investigate reasons for noncompliance. | ||

| Asare [65] | Ghana | Cross-sectional study | to estimate the proportion of children with uncorrected refractive errors eligible for ready-made spectacles in a school-based programme | ||

| Kumaran [62] | India | Cross-sectional study | to analyze the relationship between the facial and frame measurements in a sample of spectacle-wearing children in southern India | ||

| Minakaran [64] | India | Economic evaluation | to estimate potential cost- savings if ready-made spectacles were also available for dispensing | ||

| Outcomes (other) | Hashemi [70] | Iran | Cross-sectional study | to determine the prevalence of the unmet need for refractive correction and the spectacle coverage rate among 7-year-old Iranian children with refractive errors. | |

| Physical environment | Physical environment (classrooms) | Amiebenomo [75] | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | to determine the proportion of students meeting the visual acuity demand for their classrooms |

| Negiloni [74] | India | Cross-sectional study | to evaluate the distance and near visual acuity demand in Indian school classrooms and their comparison with the recommended vision standards | ||

| Physical environment (digital devices) | Dahal [80] | Nepal | Cross-sectional study | to report the pattern, symptom and associated risk factors of digital eye strain among the Nepalese school children attending online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic | |

| Gupta [81] | India | Cross-sectional study | to assess digital eye strain among schoolchildren during lockdown | ||

| Ichhpujani [76] | India | Cross-sectional study | to evaluate the use of digital devices, reading habits and the prevalence of eyestrain among urbanIndian school children | ||

| Rao [79] | India | Cross-sectional study | to assess and understand the nature and magnitude of dry eye disease-related symptoms among school children of different age groups and teacher and to suggest preventive or remedial measure | ||

| Socio-emotional environment | Students’ perceptions | Alrasheed [72] | Sudan | Cross-sectional study | to assess the attitudes and perceptions of Sudanese high school students and their parents towards spectacle wear |

| Bodunde [73] | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | to determine the perception of red eye and its associated factors among secondary school students in Sagamu, Nigeria | ||

| Burnett [59] | Cambodia | Cross-sectional study | to determine willingness to pay for children’s spectacles, and barriers to purchasing children’s spectacles in Cambodia | ||

| Parents’ perceptions | Ebeigbe [66] | Nigeria | Qualitative research | to determine the factors that influence eye care seeking behaviour of parents for their children in Nigeria | |

| Lohfeld [67] | Nigeria | Qualitative research | to understand the reasons for parents’ referral non-adherence in CrossRiver State, Nigeria, using qualitative methods | ||

| School curriculum | Eye health knowledge | Alemayehu [37] | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | to determine knowledge, attitude and associated factors among primary school teachers regarding refractive error in school children in Gondar city |

| Assefa [82] | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | Assess the level of knowledge and attitude of refractive error among public high school students in Gondar city, Northwest Ethiopia. | ||

| Ceesay [35] | Ghana | Cross-sectional study | to determine the knowledge of teachers on the nature of eye problems among schoolchildren and their ability to recognise visual disorders | ||

| Habiba [84] | Pakistan | Cross-sectional study | to determine the primary school teachers’ level of knowledge about common eye problems, their prevention, and best treatment options, and to assess the general practices of teachers regarding eye care, prevention, and treatment of eye problems in their students | ||

| Oguego [83] | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | to identify eye health myths and misconceptions that are considered true in a population of nigerian school children, with the aim of prioritizing eye health messages. | ||

| Sukati [36] | Eswatini | Cross-sectional study | to determine the knowledge and practices of teachers about child eye healthcare in the public sector in Swaziland | ||

| Sukati [89] | Eswatini | Cross-sectional study | to determine the knowledge and practices of parents about child eye healthcare | ||

| Health promotion | Narayanan [88] | India | Non-randomised experimental study | to evaluate the effect of an intervention package on compliance to spectacle wear and referral in a school vision screening programme | |

| Paudel [85] | Vietnam | Cross-sectional interventional study | to assess the effect of eye health promotion interventions on eye health literacy in school children in Vietnam | ||

| Health promotion (Myopia) | Arafa [90] | Egypt | Cross-sectional study | to detect the prevalence and risk factors of RE among preparatory school students in Beni-Suef, Egypt | |

| Assem [91] | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | to assess the prevalence and associated factors of myopia among school children in Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia | ||

| Atowa [92] | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | to assess the influence of near work, time outdoor and parental myopia on the prevalence of myopia in school children in Aba, Nigeria | ||

| Bezabih [93] | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | to assess the prevalence and identifying factors associated with visual impairment among school-age children in Ethiopia | ||

| Chhabra [78] | India | Cross-sectional study | to determine the association of near work and dim light with myopia among school children in a district in North India | ||

| Gebru [94] | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | to determine the prevalence and factors associated with myopia among high school students | ||

| Gopalakrishnan [95] | India | Cross-sectional study | to investigate the environmental risk factors associated with myopia among adolescent schoolchildren in South India | ||

| Hung [96] | Vietnam | Case control study based on cross-sectional study | to assess the prevalence of myopia and associated factors among secondary school children in a rural area of Vietnam | ||

| Saara [77] | India | Cross-sectional study | to understand the current status of refractive errors among children from public schools in southern India | ||

| Health promotion (Myopia) | Saxena [97] | India | Prospective longitudinal study | to evaluate the incidence and progression of myopia and factors associated with progression of myopia in school-going children in Delhi. | |

| Saxena [98] | India | Case control study | to assess the prevalence of myopia and its risk factors in rural school children | ||

| Singh [99] | India | Cross-sectional study | to assess the prevalence and associated behavioural risk factors of myopia in schoolchildren in Gurugram, Haryana, in north India | ||

| Community partnership | Community involvement | Chan [87] | Tanzania | Prospective longitudinal | to assess the ability of Vision Champion in identifying and referring children and the community with refractive error and obvious ocular disease and to assess the change in knowledge and practice of eye health-seeking behaviour of the community 3 months after the introduction of the Vision Champion Programme. |

| Chan [101] | Tanzania | Intervention evaluation | to identify the local barriers, needs, attitudes and behaviours regarding the potential utilisation of an arts-based approach to increase the uptake of child eye health services in Zanzibar; to describe the process of community engagement and public authority involvement in the ZANZI-ACE projects, its outcomes and the lessons learnt | ||

| Sabherwal [103] | India | Cross-sectional study | to consider the extent to which school-based screening is sufficient to achieve universal eye health coverage of children in a rural agricultural setting in north India, where low school enrolment and absenteeism may be common | ||

| School governance and leadership | Leadership | Ayorinde [86] | Nigeria | Intervention evaluation | to determine if primary school pupils aged 9–14 years can be satisfactorily trained, using the child-to-parent approach, to assess vision, refer and motivate people to attend screening eye camps |

| School policies | Integration (school health) | Chan [104] | Tanzania | Economic evaluation | to review and compare the cost-effectiveness of the integrated model (IM) and vertical model (VM) of school eye health programme in Zanzibar |

| Chan [23] | Tanzania | Intervention evaluation | to determine the performances of an integrated (IM) and vertical (VM) school eye health programme | ||

| Government policies | Integration (National) | Atowa [12] | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | to evaluate the coverage, components, and referral criteria of the paediatric vision screening services in Abia State, Nigeria, towards the development of a uniform vision screening guideline |

| Engels [38] | Cambodia and Ghana | Economic evaluation | to estimate the cost of integrating vision screening and provision of spectacles in existing national school health programmes in Cambodia and Ghana | ||

| Seelam [102] | India | Qualitative research | to understand how a large-scale, comprehensive school eye health programme, the Refractive Errors Among Children (REACH) programme, operated in six districts in India, and how it translated into improved performance with respects to programme implementation and optimised use of resources. | ||

| Sukati [68] | Eswatini | Cross-sectional study | to determine the knowledge and practices of eye health professionals about the availability and accessibility of child eye care services in the public sector in Swaziland | ||

| Yashadhana [34] | Malawi | Qualitative research | to explore the availability and accessibility of school-based eye health programmes in Malawian primary schools in the central region, and identify key factors that either inhibit or facilitate their successful provision (included exploring existing NGO-funded school-based eye programmes, as well as the potential for government-funded programmes) | ||

| Yong [105] | Mongolia | Economic evaluation | to estimate the net benefits of a children’s spectacles reimbursement scheme in Mongolia | ||

| Yong [100] | Zambia | Scalability assessment | to identify and evaluate the essential components of an effective SEHP, determine roles, assess existing capacities within user organisations, identify environmental facilitating and inhibiting factors, and estimate the minimum resources necessary for the scaling up and their proposed scale-up strategies |

HPS Health Promoting School Framework.

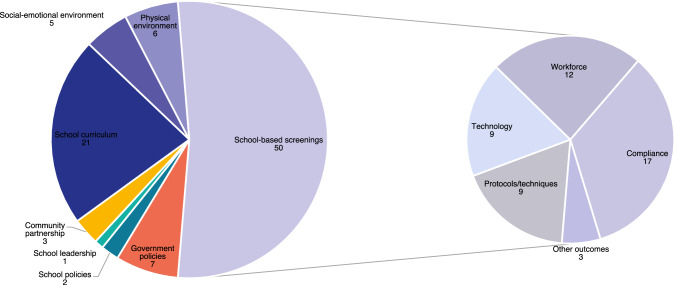

Figure 3 shows the volume of publications for each HPS theme. The school health service delivery is the main theme discussed in the selected studies.

Fig. 3. Number of selected publications sorted by HPS main themes.

SEHP school eye health programmes, M&E monitoring and evaluation, VA visual acuity, RE refractive error.

School-based screenings

More than half of the selected studies focused on delivery components of school-based visual screenings (n = 50), such as protocols and techniques (n = 9), new technologies (n = 9), workforce (n = 12), and outcomes (n = 20).

Screening protocols

There is a multitude of school-based vision screening protocols described in recent studies, ranging from basic visual acuity assessment to comprehensive examinations by eye care professionals, some even including opportunistic screening for vitamin A deficiency [11]. Large variations were noted between studies with regards to visual acuity cut-offs, charts used, and refractive error definitions, making comparison of outcomes challenging (see Table 2). Almost half of the selected studies used 6/12 as a cut-off, but most used 6/9, and these were mainly in India.

Table 2.

Characteristics of school-based visual screenings.

| Components of screenings | Criteria used | Number of studies |

|---|---|---|

| Distance VA | ||

| VA cut-off | 6/9 | 24 |

| 6/12 | 22 | |

| Charts | Tumbling E | 18 |

| Snellen | 10 | |

| LogMAR chart | 6 | |

| Primary screening with ‘E’ + secondary screening with Snellen or LogMAR chart | 5 | |

| Other | 3 | |

| Near vision testing | ||

| Fogging with plus lenses | +1.50 | 2 |

| +2.00 | 2 | |

| +2.50 | 1 | |

| Near VA chart | 2 | |

| Complaints | 2 | |

| Rx definitions | ||

| Myopia | >−0.50D | 17 |

| >−0.75D | 5 | |

| Hyperopia | <+1.00 | 3 |

| >+1.00 | 5 | |

| >+2.00 | 4 | |

| >+2.50 | 2 | |

| >3.00 | 2 | |

| Astigmatism | 0.50 | 7 |

| 0.75 | 2 | |

| 1.00 | 5 | |

Disparities are documented even within countries, as demonstrated in a survey from Nigeria where 100% of the optometrists doing vision screening were including VA and ocular health assessment, 71.4% tested near vision, 35.7% evaluated for strabismus and only 14.2% did a refraction with retinoscopy or an autorefractor [12]. While distance VA assessment alone has been shown to be inefficient for screening, the addition of retinoscopy significantly increases the accuracy of screenings but requires skilled screeners [13]. Instrument-based screenings using portable focometers or autorefractors are easier to use but less accurate [14, 15]. Similarly, non-cycloplegic refraction is known to underestimate hyperopia and overestimate myopia in school-aged children [15], but the gold standard of cycloplegic refraction is not practical in school settings due to the parents’ consent and side effects of the drops [16, 17]. Non-cycloplegic spectacle correction was not greater than the clinically tolerable level of 0.5D in a study by Khurana [16], thus, it is suggested that non-cycloplegic refractions can be accepted if there are social, economic or logistical constraints. However, children should be referred for cycloplegic refraction when presenting with high levels of myopia, hyperopia or binocular vision issues [16, 17].

Rigorous and standardised protocols were described in a few studies. A structured protocol based on the WHO recommendations for Primary Eye Care in Africa has successfully been tested in Kenya, showing that it can be transferred to school settings [18]. Also, at least three programmes [16, 17, 19] were based on the Refractive Error Study in Children (RESC) protocol, published in 2000. Similarly, multi-stage screenings are largely documented in India, being a time- and cost-effective model in low-resources settings, with its effective use of skilled human resources [20]. The large-scale REACH programme includes an initial screening by teachers with vision assessment, +1.50 lens test, torch light examination, and colour vision for boys in graders 8–12. A detailed examination is provided to identified children the same day, on-site by an optometrist, with a retinoscopy, subjective refraction, cover test, torch light and direct ophthalmoscopy when needed. Children needing further evaluation are then referred to tertiary services. A 6-months unannounced visit is organized to monitor compliance and an annual follow-up cycle is planned. All data is registered in digital records, allowing monitoring progress and facilitating management. This standardised protocol has been implemented in more than 10,000 schools across five states in India and more than 2,000,000 children 5–18 years old underwent screening [21]. An economic evaluation of this programme has shown that costs were low even with this comprehensive model [22].

Lastly, timing of screenings has been mentioned by few authors as an important issue to consider when organizing SEHP as seasonal variations may affect the screening’s coverage [23, 24].

Technology

Many new technologies for school-based screenings have been evaluated recently, aiming to improve efficiency of programmes. However, evidence is not very robust for most of them.

Different photoscreeners have been compared to subjective or cycloplegic refractions, with overall limited results. In fact, self-adjustable spectacles have been compared to cycloplegic refraction with clinically significative differences in two studies [25, 26]. Similarly, the Welch Allyn Spot Vision Screener™ (Skaneateles Falls, USA) overestimated hyperopia and underestimated myopia but overall refraction values were considered acceptable for a screening test. Being more portable than a traditional photorefractor, it can act as a guide for subjective correction, but not a replacement for retinoscopy [27]. Other authors have explored the PlusOptix A09 (Nuremberg, Germany), the most commonly used screening tool for paediatric populations [28]. The portable vision screener showed a minimal time for screening a child (4 s) and better cost-effectiveness compared to other photoscreeners and Mohindra, but variable validity [28–30].

Validity of smartphone fundus photographs that capture the undilated Bruckner’s reflex has also been assessed to detect ocular morbidities. Photographs has shown good validity when researchers agreed on interpretation, but lower validity when disagreement (13% of photographs). Moreover, 13% of children have been excluded of the study due to poor quality of photographs [31].

Lastly, few studies evaluated Peek Vision, an app-based package developed to optimise outcomes of school-based screenings. There has been a significant improvement in referral rates with the Peek school eye health system [32], but no difference in spectacle wear at 3–4 months follow-up with the health education intervention [33]. It has also been shown that Peek Acuity can be successfully used by teachers but had a higher rate of false positive than standard screening [32].

Therefore, while these technologies are promising, more evidence from LMICs will be needed.

Workforce

Twelve of the selected studies evaluated human resources performing school-based vision screenings, most of them involving teachers as screeners.

Conducting vision screenings is generally accepted by teachers, eye care professionals, and parents [34–37]. Vision screening by teacher is less costly than alternative primary eye care models [38] and shows overall good outcomes, especially with older children [19, 20, 39, 40]. However, validity of screenings by teachers is variable when compared to eye care professionals as shown in Table 3a [19, 20, 39–44]. Challenges reported by teachers in Pakistan include lack of training, heavy workload, and lack of time [45]. Therefore, authors recommend support of teachers with ongoing motivation, sufficient and standardised training, annual refresher courses, written guidelines, and supervision [20, 40, 45, 46]. Strong monitoring and quality assurances are also needed to improve quality of screenings by teachers and limit potential workload of qualified eye care teams [42, 43]. Interestingly, teachers in Zanzibar had better validity in screenings when vision screenings were integrated with a nutrition programme compared to vision screening only [23].

Table 3.

Reported validity of screeners in selected studies.

| 3a. Validity of teachers | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workforce | Kaur [43] | Paudel [39] | Rewri [19] | Marmamula [44] | Panda [20] | Shukla [41] | Muralidhar [40] | Tobi [42] | Sabherwal [46] | |||

| uncorrected VA | corrected VA (when needed) | children with severe VI | Class teachers | Selected teachers | ||||||||

| Sensitivity | 46.0% | 86.7% | 75.3% | 47.7% | 69.2% | 72.3% | 80.5% | 92.3% | 24.8% | 25.0% | 36.0% | 44.3% |

| Specificity | 95.7% | 95.7% | 93.0% | 99.2% | 95.3% | 99.9% | 53.3% | 72.6% | 98.7% | 99.6% | 96.1% | 91.2% |

| PPV | 47.2% | 86.7% | 69.5% | 72.4% | 83.5% | 92.3% | 93.0% | 68.9% | 34.9% | 66.7% | 42.5% | 30.1% |

| NPV | 95.7% | 95.7% | 94.7% | 97.9% | 89.8% | 99.5% | 26.0% | 93.4% | 97.8% | 97.8% | 42.0% | 95.0% |

| 3b. Validity of other screeners | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workforce | Marmamula [44] | Dole [47] | Sabherwal [46] | Mathenge [18] | |

| CHW | Experienced community vision screeners | Unexperienced community vision screeners | Vision technicians | Allied health trainees | |

| Sensitivity | 83.3% | 100.0% | 67.5% | 93.3% | 100.0% |

| Specificity | 99.8% | 100.0% | 99.7% | 98.7% | 97.2% |

| PPV | 85.4% | 100.0% | NE | 81.2% | NE |

| NPV | 99.7% | 100.0% | NE | 99.6% | NE |

Some authors recently compared validity of alternative screeners such as community health workers (CHW) [44, 47], vision technicians [46] or allied health trainees [18], and obtained overall better outcomes than teachers (see Table 3b). This suggests that community-level workers may be more efficient primary screeners [46]. However, they also showed a lack of training, shortage of available workforce, and reduced access to transport in Malawi [34].

Lastly, student-led screenings in Nepal have been shown to be a cost-effective model for countries with limited financial resources [48], but it is not an effective approach according to eye care professionals in Pakistan [45].

Outcomes

The ultimate outcome for vision screening is to achieve better educational outcomes through good vision. In fact, children with uncorrected refractive errors have significantly lower academic results than normal-sighted children [49], and children with adequate correction have better academic results after wearing spectacles [50].

Nevertheless, spectacle wear rates at follow-ups are generally low, ranging from 0% [51] to 65.9% [52]. Better compliance rates are reported with children presenting myopia and when they notice a vision improvement with their spectacles [51–55]. Indeed, students with initial VA worse than 6/18 in the better eye were almost three times more likely to be wearing their spectacles than those with better presenting VA [56]. Another study in India demonstrated that spectacle use increase by 10% with refractive errors over 0.75D [55]. Correlations between better compliance and other factors were generally not consistent from one study to the other, except for parents wearing spectacles and those with higher education [51, 53, 57, 58].

Broken and lost frames are the main factors mentioned by children for non-spectacle use, in addition to lack of frame measurements and consequential discomfort [23, 24, 26, 41, 51–55, 58–61]. Indeed, large variations between facial and frames measurements are reported, and 8% of selected children in India were wearing adult frames at follow-up [55, 62]. Moreover, Indian students mentioned that they expected trendy, stylish and resistant spectacles, so providing proper quality frames adapted to children and following their preferences when choosing frames has been suggested to improve compliance after school screenings [24, 55, 61, 63]. Ready-made spectacles can be a cost-effective and acceptable alternative to custom-made spectacles, with similar spectacle wear rates and symptoms of discomfort than custom-made spectacles [56], and potential cost-savings for national programmes [38, 64]. Respectively 86.0% and 86.7% of children in India and Ghana were eligible to ‘ready-to-clip’ spectacles [56, 65].

Additionally, stakeholders often cited concerns about spectacle affordability [24, 34, 59, 61, 66–68]. In fact, unmet needs and spectacle coverage rate was found to be significantly lower in low-income families in multiple settings and out-of-pocket payments may limit access to eye care [68–70]. Therefore, financial input from the community, in the form of health insurance or other support, is required to ensure equity in spectacle provisions [59, 68]. An economic evaluation by Burnett et al. showed that a tier pricing structure based on capacity to pay could improve equity to access quality frames and decrease the dependence on external funding [59]. A public-private partnership with local eye clinics is another suggested model for providing subsidised spectacles to children after school vision screening when costs are prohibitive, leading to better compliance rates [52]. Indeed, free spectacles have been shown to be beneficial when delivered directly in school, with a majority of parents feeling good about them when they are of good quality [59, 61].

Logistics and geographic issues were also mentioned as significant barriers to compliance, namely due to misunderstanding of referral letters, restricted time off from work and transport to clinics limit access to the required follow-ups in rural regions [34, 59, 66, 67]. Lastly, parents’ disapproval and friends teasing are other frequently cited reasons for non-wear of spectacles, as discussed in the next section.

Socio-emotional and physical environments

The HPS framework stipulates that schools should provide favourable social and physical environments for school-based health services [9]. Despite this recommendation, social stigma is still one of the main barriers to spectacle wear cited by students. When asked about non-wear of spectacles, they frequently mention fear, teasing, peer pressure and family disapproval [23, 34, 41, 51, 54, 57, 59, 61, 71, 72]. Parents also demonstrate negative perceptions towards spectacles, such as not believing that their child needs correction, being concerned by the risk of dependency, of potential damage to their child’s eyes, a lack of trust in modern medicine or apprehensions towards marriage prospects [23, 24, 34, 41, 54, 55, 57, 59, 61, 66, 67, 73]. Nevertheless, most parents agree that school screenings and eye care services are important, so authors agree that these concerns should be assessed through eye health education, better training, and parents’ counselling in order to improve SEH programmes outcomes.

Similarly, physical environments are not always adequate either to students’ needs, as shown in three studies. In Chennai, 21% of classrooms had a distance visual demand over a 6/9 visual acuity (VA) equivalent, meaning that children who pass screening at that threshold may suffer from visual stress [74]. In Nigeria, 9.4% of children did not meet the required visual acuity to meet the classroom demands [75]. Additionally, near visual demand is greater for children who read at a very close distance (25 cm), therefore increasing the risk for asthenopia [74–76]. Authors recommend that school authorities should be aware of those constraints and should accommodate visually impaired children [74, 75].

Finally, few studies assessed the visual impact of online classes, especially during COVID-19. No causal link has been shown between home confinement, digital use and with myopia progression during that specific period [77, 78]. However, increased use of digital device has been associated with eyestrain and dry eyes [76, 79–81]. Considering that online education and digital tools may remain in schools, preventive interventions such as adequate refractive error correction, sufficient ambient lighting and limiting screen time is suggested by Gupta to reduce asthenopia for schoolchildren [81].

School curriculum

According to the WHO, health-promoting schools should encourage health literacy by integrating health education in school curricula. In fact, many studies reported significant gaps in students’ [23, 82, 83] and teachers’ [37, 84] knowledge on eye health, which are associated with noncompliance in spectacle wear after screenings. In Ethiopia, only 55% of teachers had good knowledge and favourable attitude towards eye health and refractive errors [37]. While levels were higher in Ghana (60%–75%), only 39% of respondents thought that eye problems could lead to poor academic performance [35].

Even so, most of the eye health promotion activities included in selected studies were limited to education of students and parents on importance of spectacle wear. Comprehensive health promotion activities can however lead to improved knowledge on eye health [85, 86]. In Tanzania, students trained as vision champions improved their community’s eye health knowledge by sharing eye health messages to their families and neighbours [87]. Eye care service utilisation also increased significantly after a one-week eye health promotion in Vietnam, with the proportion of children reporting to have had an eye check-up going from 63.3% before the intervention up to 84.7% after the health promotion activities [85]. However, this intervention did not lead to a significant increase of spectacle compliance rates, similarly to results obtained after close follow-ups by ophthalmologists in Nepal [57]. Better outcomes on spectacle wear and compliance to referral were found in India with a 23-step protocol based on frames and fit, education, and motivation [88]. The intervention was based on barriers and solutions described by local stakeholders, and required continuous planning and follow-up, but ultimately led to a change of behaviour from the students, teachers, and parents [88]. Additional strategies were suggested in the literature to promote eye health message and raise community awareness, such as integration of eye health messages in school curriculum [36, 61, 82–84], teachers’ follow-ups to parents [26], workshops on eye health and use of social and mainstream media [36, 37, 42, 68, 89].

Finally, new eye health education messages that are mentioned in recent literature focus mainly on myopia prevention. In fact, 12 of the selected studies associated myopia prevalence with behavioural risk factors such as near work, limited outdoor activities, time spent in front of TV, computer games, mobile exposure, and type of schooling [77, 78, 90–99]. However, results are very inconsistent, and no causal link could be established in either of these cross-sectional studies, even though stronger associations were found between myopia prevalence, reduced outdoor activities, and prolonged near work [77, 78, 91, 92, 94–99]. According to these authors, parents should be informed of risk factors and school curricula should promote a healthy balance between classroom time and time spent outdoors [78, 92, 96–99].

Community partnerships

Active engagement from parents and local communities are essential to implement health-promoting schools [9]. Many publications showed the significant influence that community members, and particularly parents, can have in service uptake and adherence to treatments after SEH interventions [67, 100]. Many authors agree that parents should also be educated and counselled about the benefits of wearing spectacles, and may even be present during vision screening activities [24, 66, 67, 72, 89].

Interventions based on community participation and co-creation were described through the development of locally relevant interventions and eye health promotion material in Tanzania, India, and Vietnam [21, 85, 88, 100–102]. For example, a co-creation workshop engaging key stakeholders in Zanzibar demonstrated that broadcasting songs/music containing eye health messages through a local radio station is a locally relevant, well-accepted, and cost-efficient way to improve awareness [101].

Collaboration with local eye care providers is also recommend to ensure continuous eye health services in the community after the school screenings [12, 68]. However, school screenings can lead to a subsequent overload for local centres as demonstrated in Chan 2017, where a community-based health promotion activity in Zanzibar increased the number of patients at the local vision centre by 417% [87].

Interestingly, two publications mentioned the lack of coverage for children who are not attending school. [42, 103]. Authors noted very high absenteeism rates in some regions (up to 31.8% in rural India) and suggested that stakeholders reflect on how to reach those out-of-school children, potentially with community-based platforms [42, 103].

School governance and leadership

The WHO’s HPS framework mentions that strong school governance and leadership is required to create a solid link between the school leaders, local communities, and governmental instances. None of the selected articles specifically focused on governance, but seven studies mentioned that engaging students and teachers in screening activities is a powerful strategy for programme implementation [23, 24, 45, 51, 61, 86, 100]. In fact, teachers are more dedicated when supported by enabling environments with sufficient training and incentives, leading to better implementation and compliance amongst children after screenings [23, 45, 51, 61]. Therefore, teachers’ personal motivation, interests and commitments should be considered when selecting them for vision screenings [45].

Similarly, students’ empowerment in child-to-child approaches has been effective to improve children’s awareness and attitude towards visual impairment in a small-scale community-based initiative in Nigeria [86]. Show-casting compliant children as role models has also been mentioned as a solution to improve compliance in India [24].

School policies

Integration of school-based health services in school policies is a key factor for sustainability of programmes [9], and is discussed in recent literature on school eye health. In fact, pairing SEH with existing school health activities such as feeding programmes can be more efficient and cost-effective than an isolated, vertical SEHP model, as shown in a project in Zanzibar [23, 104]. This integrated approach minimises costs through inter-sectoral collaboration in key activities such as stakeholders’ mobilisation and training [38, 104]. Moreover, this model showed better outcomes in eye health screening coverage, follow-up rate and spectacle wear rate [23], and allowed partnerships with local primary healthcare to facilitate a continuum of eye care services beyond initial screenings [18, 21].

Government policies

Lastly, the WHO advocates for long-term commitments and clear governmental policies through its HPS objectives [9]. Seven studies specifically focused on national integration and scaling of SEH programmes, with examples from Malawi, India, and Zambia [12, 34, 38, 68, 100, 102, 105]. One of the key factors for scaling SEHP reported in those publications is collaboration between NGOs, ministry of health and ministry of education [34, 100]. Ownership of the programme by the government is also crucial to ensure full support through funding and human resources allocation and lead to sustainable programmes, considering that durable initiatives will not be possible if only relying on NGO’s funding [34, 100]. Economic evaluations demonstrated that the delivery of the school-based vision screening programmes at scale was affordable for governments in Cambodia and Ghana, and that government-subsidized spectacles through social health insurance could be a potential long-term financing solution [38, 105]. Advocacy for policy changes and continuous efforts for capacity strengthening are also required for sustainable programmes. Local stakeholders in Eswatini, Malawi, and Zambia mentioned that eye health is not always a priority compared to others health disciplines and lack of data can be a challenge for advocacy, planning, and budgeting interventions [34, 38, 68, 100].

At an operational level, large-scale SEH programmes are feasible due to key components such as community engagement, co-designed model of care for a context-adapted, comprehensive protocol, and rigorous programme monitoring and evaluation [102]. However, lack of clear frameworks, legislation, and policies to structure eye health practices and inefficient pathways between schools and health services have been barriers to programme delivery in low-resources settings [12, 34, 68, 100, 102]. In fact, 14.3% of Nigerian optometrists have to organize outreaches by themselves, which limits the frequency of vision screening [12].

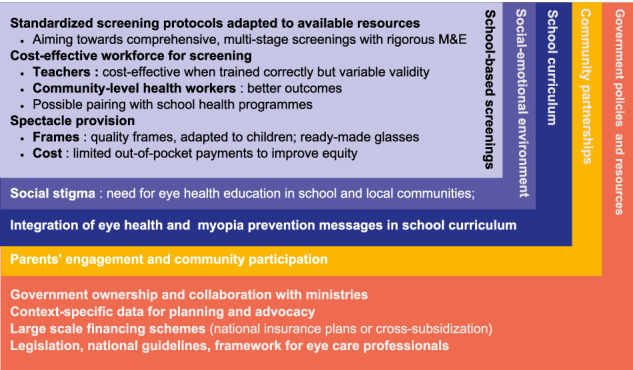

To summarize, main priorities from in recent literature are identified in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Priorities in school-eye health for low–middle-income countries.

Themes from literature on SEH are presented based on some of the main HPS framework components: school-based services, social–emotional environment, school curriculum, community partnerships, government policies and resources. M&E monitoring & evaluation.

Discussion

This study provides updated data and identifies current priorities for stakeholders involved in school eye health programmes. Publications were analyzed through the WHO’s Health-Promoting Schools framework, an ecological approach for durable and integrated programmes conducted in school settings. Results demonstrate the complexity of effective school-based health services such as vision screenings and illustrate the many challenges to overcome in order to achieve sustainable initiatives embedded in effective eye care services pathways. Main priorities identified throughout in this work are protocols, compliance to spectacle wear, human resources, national integration, and financing. These findings are concordant with other systematic reviews on the topic published in the past years [3, 4, 106, 107].

First of all, findings in his study demonstrated a wide disparity in school-eye health programmes delivery. While multi-stage screenings have been largely implemented in India, basic protocols restricted to distance VA assessment and ocular health assessment are described in most LMICs. In fact, limited resources, equipment, and support can restrain implementation of standardised, comprehensive protocols with routine examinations [3, 4, 106, 107].

Discrepancies around the visual acuity threshold used for school-based screenings is one of the most significant aspect of protocols that can impact programmes’ delivery, and stakeholders should reflect on it wisely when planning SEHP. In fact, almost half of programmes in selected studies currently use 6/12 as VA cut-off, in accordance with the WHO’s recommended indicator for distance vision coverage (eREC) [108]. This indicator is important for standardisation and limits the cost of programmes by reducing the rate of false positives. Moreover, better spectacles wear rates are obtained with children presenting significant refractive errors and lower initial VA due to an increased perceived benefit [107, 109]. However, this threshold might fail to identify children with small refractive errors, which can be critical in some classrooms with high visual demands, poor lighting, and low-contrast blackboards. Consequently, global paediatric guidelines advocate for 6/9 considering children’s excellent visual potential [2, 110]. Recent recommendations on myopia prevention also include full correction of myopia to reduce its progression [111]. Therefore, 6/9 should be aimed for in regions with increasing myopia prevalence to allow early identification and management of children at risk, but 6/12 can be an acceptable option when resources are limited. Additionally, other tests should be considered to detect hyperopia, a refractive error that does not affect distance vision but is associated with lower academic performance [112].

Variability in charts used, and prescribing criteria are other aspects which impact significatively programme delivery. Global guidelines provide specific prescription criteria and encourage the use of age-appropriated, validated logMAR charts to ensure rigorous and comparable outcomes [5, 110]. Also, while many new technologies have been developed recently to facilitate screenings, more evidence is needed before replacing current techniques.

Secondly, results in this review have shown a significant interest for outcomes of school-based screenings, mainly compliance to spectacle wear. It is understandably a concern for stakeholders considering that poor compliance may reduce the cost-effectiveness of programmes and leave many children with suboptimal vision that can potentially limit their educational potential [22, 112–114]. Spectacle wear is generally low at follow-ups in the selected studies, and reasons for noncompliance vary largely between settings, enhancing the need for strong monitoring and evaluation. Context-specific data is also required to understand local socio-cultural factors leading to non-wear of spectacles, and findings should be taken into consideration when developing locally adapted eye health education material [109]. Health promotion activities should also include community participation, leadership from students, and teachers, and involve parents in order to reduce social stigma, gaps in knowledge and negative attitudes towards eye care [107, 109]. Moreover, integration of eye health in school curriculum is suggested to increase eye health literacy [107], and should now include myopia prevention advice considering its rapid increase in prevalence in schoolchildren [1, 111, 115]. In fact, while evidence in selected studies was inconsistent, global guidelines recommend to reduce close reading distance, take frequent breaks while reading, and spend a minimum of two hours per day outdoors [111, 115, 116].

Other significant factors for noncompliance to spectacle wear are broken or lost spectacles, discomfort, dislike of frame, and peer teasing/bullying. This highlights the need for provision of quality spectacles after screenings, with frames suitable for children features and corresponding to their liking. An acceptable and cost-efficient solution for most children is ready-made spectacles, but they need to be prescribed in accordance with guidelines [107, 114, 117]. Moreover, programme-makers need to ensure continuous access to eye care providers in order to replace spectacles when required [107, 109]. Collaboration with local professionals and efficient pathways of care are therefore essential for integrated and sustainable programmes.

Lack of human resources is another significant challenge for SEHP delivery in LMICs [4], and evaluation of different screeners for their sensitivity and specificity is a major topic discussed in the literature. As mentioned previously, teachers are currently key actors in school-based visual screenings due their proximity with children. In fact, initial screenings by teachers are accurate and cost-effective when trained correctly, in accordance with results from other systematic reviews [4, 107]. Yet, their work overload, insufficient training, and lack of time may lead to variable results and debatable validity. Low specificity (high rates of false positives) result in unnecessary re-examinations of normal children, increasing programmes’ costs and overburden for local eye care providers and parents. Conversely, low sensitivity (high rates of false negatives) can be very problematic as visually impaired children may be missed and compromise the quality of the programme [42, 43]. Therefore, selection of motivated teachers, strong support, annual refresher course, supervision and monitoring is required to ensure quality of screenings by teachers. However, other community-level health workers can conduct school-based screenings, as recommended in the WHO’s eye care competency framework [118]. In fact, community-level health workers showed better overall validity in school screenings, and while no selected publications demonstrated the validity of nurses in this study, Burnett et al. demonstrated that they can be a practical and cost-effective workforce to carry preventive and health promotion work [4, 107]. Teachers can be involved in many other aspects of school eye health programmes, such as scheduling referrals and communicating outcomes to the school-based community [107].

Finally, few publications focused on policy-level challenges such as integration of school eye health in other school health interventions, scaling of programmes, and long-term financing and sustainability. In fact, other systematic reviews reported that political and socio-economic issues such as lack of financing, human resources and infrastructures limit the capacity of LMICs to implement and deliver mass school-based vision and eye health screenings [4, 106, 107]. Currently, most programmes are vertical, isolated, and NGO-driven, and multi-level collaboration is required to develop and successfully scaled-up SEH programmes. Pairing with other school health programmes can be envisaged to share financial and human resources [107]. Moreover, government ownership and collaboration between ministries of Health, Education and even Finance are essential to support long-term sustainable initiatives with adequate financial and human resources. In fact, cost of services and spectacles is a major barrier to eye care coverage and compliance after SEHPs, especially for low-income families [107]. According to Evans et al., school screening programmes which provide free spectacles have better outcomes at follow-ups than those that do not [114]. Therefore, financial schemes such as national insurance plans or cross-subsidisation should be considered to limit out-of-pockets payments for parents, improve equity to eye care and reduce dependency on NGOs. Burnett et al. mentioned that inclusion of eye health in governmental strategic plans and health budgets are key political determinants for SEH programmes, even if close partnerships with NGOs are sometimes necessary for additional support [107]. However, prioritisation of eye care at national levels may remain a challenge [106] and context-specific, quality data are required to advocate for policy changes. Efficient referral pathways, clear frameworks, legislation, and standardised guidelines are also needed by local eye care professionals to structure their practice and facilitate scaling of SEH programmes.

Limitations

This study has many limitations. First, only one reviewer (AH) performed most of the article selection and data extraction, and no critical appraisal of quality has been done on selected articles. Secondly, it is important to note that volume of research may not be representative of stakeholders’ real priorities, and abundant publications on compliance and myopia may only result from simpler study designs. By opposition, economic evaluation and sustainability assessment are complex designs that requires significant resources and may not be possible to conduct in every setting. Priorities also vary widely between middle-income and lower-income settings, where resources and eye care delivery systems may be much more limited. Resource mapping is therefore an important step in planning programmes to ensure protocols adapted to available workforce.

Moreover, this work focused on school-going children. However, neonatal, infant and preschool visual screenings are also important to consider to detect congenital and early-onset ocular problems [4]. Similarly, most selected studies focused on refractive errors, but it is important to recognise that refractive error may not be the most prevalent condition in all countries, as ocular diseases such as allergies and trachoma may be a concern for children in some LMICs [10]. Also, despite a search in four databases, none of the retained articles came from LMICs in Latin or South America, limiting the representativeness of the results.

Interestingly, there is no major gender inequalities reported in selected studies. However, recent global studies demonstrated that girls have a higher burden from refractive disorders due in part by a lack of access to healthcare for girls and gender-based barriers within parental-decision making [107, 119]. Gender-specific policies is therefore recommended when designing SEHPs [107, 119]. Reaching out-of-school children and those with disabilities should also be taken in consideration during planning [107].

Conclusion

School eye health initiatives have the potential to improve life of millions of children globally, especially in LMIC. This scoping review demonstrates that multi-level and multi-sectoral action is required to implement sustainable and integrated school eye health programmes in low and middle-income countries. Based on the Health Promoting Schools framework, the main priorities identified in this review have highlighted the need for:

Rigorous and standardised protocols based on available human and financial resources, with strong monitoring and evaluation

In-depth understanding of local barriers to spectacle wear in order to provide suitable spectacles that correspond to children’s liking and comfort

Creation of locally adapted eye health education material and health promotion activities based on leadership and participation

Inclusion of eye health and myopia prevention in school curricula

Strong partnerships with other school health programmes, communities and local eye care providers for integrated pathways of care

Government involvement and inter-sectoral collaboration between ministries for long-term national plans, with support from NGOs when needed

Advocacy for prioritisation of eye care in national plans, including standardised guidelines, legislation and frameworks for eye care providers

Even if many challenges remain, the continuous production of quality data such as the ones presented in this review will help governments and other stakeholders to build evidence-based, comprehensive, integrated and context-adapted programmes and deliver quality eye care services to children all over the world.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

AH was responsible for designing the search protocol, conducting the search, screen for eligible studies, extracted relevant results, sorted and analysed data. She wrote the first draft and created tables and figures. BT reviewed and edited the search protocol, advised when ambiguity arose during screening and reviewed and edited all drafts of the manuscript, PM PY reviewed and edited the search protocol and all drafts of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41433-024-03032-1.

References

- 1.Burton MJ, Ramke J, Marques AP, Bourne RRA, Congdon N, Jones I, et al. The Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health: vision beyond 2020. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e489–e551. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30488-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Agency for Prevention of Blindness. 2023. Available from: https://www.iapb.org. Accessed 7 May 2023.

- 3.Atowa UC, Wajuihian SO, Hansraj R. A review of paediatric vision screening protocols and guidelines. Int J Ophthalmol. 2019;12:1194–201. 10.18240/ijo.2019.07.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen AH, Abu Bakar NF, Arthur P. Comparison of the pediatric vision screening program in 18 countries across five continents. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2019;31:357–65. 10.1016/j.joco.2019.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbert C, Minto H, Morjaria P, Khan I. Standard school eye health guidelines for low and middle-income countries. Internation Agency for Prevention of Blindness; 2018. Available: https://www.iapb.org/wp-content/uploads/Guidelines-School-Eye-Health-Programmes-English-Final.pdf.

- 6.JBI. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. 2022. Available from: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687770/11.3+The+scoping+review+and+summary+of+the+evidence.

- 7.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2023. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 22 Feb 2023.

- 9.World Health Organization. Making every school a health-promoting school. Geneva; WHO; 2021.

- 10.World Health Organization. Report on vision. Geneva: WHO; 2019.

- 11.Panda L, Nayak S, Das T. Tribal Odisha Eye Disease Study Report # 6. Opportunistic screening of vitamin A deficiency through School Sight Program in tribal Odisha (India). Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:351–5. 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1154_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atowa UC, Wajuihian SO, Hansraj R. Towards the development of a uniform screening guideline: current status of paediatric vision screening in Abia State, Nigeria. Afr Vis Eye Health J. 2022;81:a661. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chottopadhyay T, Kaur H, Shinde AJ, Gogate PM. Why are we not doing retinoscopy in the school eye screening? Is distant visual acuity a sensitive tool for making referrals? Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2021;35:320–4. 10.4103/sjopt.sjopt_19_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aina AS, Oluleye TS, Olusanya BA. Comparison between focometer and autorefractor in the measurement of refractive error among students in underserved community of sub-Saharan Africa. Eye. 2016;30:1496–501. 10.1038/eye.2016.181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ilechie AA, Addo NA, Abraham CH, Owusu-Ansah A, Annan-Prah A. Accuracy of noncycloplegic refraction for detecting refractive errors in school-aged African children. Optom Vis Sci. 2021;98:920–8. 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khurana R, Tibrewal S, Ganesh S, Tarkar R, Nguyen PTT, Siddiqui Z, et al. Accuracy of noncycloplegic refraction performed at school screening camps. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66:806–11. 10.4103/ijo.IJO_982_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gopalakrishnan A, Hussaindeen JR, Sivaraman V, Swaminathan M, Wong YL, Armitage JA, et al. The Sankara Nethralaya Tamil Nadu Essilor Myopia (STEM) Study-defining a threshold for non-cycloplegic myopia prevalence in children. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1215. 10.3390/jcm10061215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathenge WC, Bello NR, Hess OM, Dangou J-M, Nkurikiye J, Levin AV. Use of the World Health Organization primary eye care protocol to investigate the ocular health status of school children in Rwanda. J AAPOS. 2023;27:16.e1–16.e6. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2022.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rewri P, Nagar CK, Gupta V. Vision screening of younger school children by school teachers: a pilot study in Udaipur City, Western India. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2016;11:198–203. 10.4103/2008-322X.183920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panda L, Das T, Nayak S, Barik U, Mohanta BC, Williams J, et al. Tribal Odisha Eye Disease Study (TOES # 2) Rayagada school screening program: efficacy of multistage screening of school teachers in detection of impaired vision and other ocular anomalies. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:1181–7. 10.2147/OPTH.S161417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sil A, Aggarwal P, Sil S, Mitra A, Jain E, Sheeladevi S, et al. Design and delivery of the Refractive Errors Among Children (REACH) school-based eye health programme in India. Clin Exp Optom. 2022;106:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saravanan S, Krishnamurthy S, Ramani KK, Narayanan A. Cost analysis of a comprehensive school eye screening model from India. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2022;30:196–202. 10.1080/09286586.2022.2150229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan VF, Yard E, Mashayo E, Mulewa D, Drake L, Price-Sanchez C, et al. Does an integrated school eye health delivery model perform better than a vertical model in a real-world setting? A non-randomised interventional comparative implementation study in Zanzibar. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022;0:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narayanan A, Kumar S, Ramani KK. Spectacle compliance among adolescents in Southern India: Perspectives of service providers. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66:945–9. 10.4103/ijo.IJO_27_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ocansey S, Amuda R, Abraham CH, Abu EK. Refractive error correction among urban and rural school children using two self-adjustable spectacles. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2023;8:e001202. 10.1136/bmjophth-2022-001202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ilechie AA, Abokyi S, Boadi-Kusi S, Enimah E, Ngozi E. Self-adjustable spectacle wearing compliance and associated factors among rural school children in Ghana. Optom Vis Sci: Off Publ Am Acad Optom. 2019;96:397–406. 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddy S, Panda L, Kumar A, Nayak S, Das T. Tribal Odisha Eye Disease Study # 4: accuracy and utility of photorefraction for refractive error correction in tribal Odisha (India) school screening. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66:929–33. 10.4103/ijo.IJO_74_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prabhu AV, Thomas J, Ve RS, Biswas S. Performance of Plusoptix A09 photo screener in refractive error screening in school children aged between 5 and 15 years in the southern part of India. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2020;32:268–73. 10.4103/JOCO.JOCO_76_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murali K, Vidhya C, Murthy SR, Mallapa S. Cost-effectiveness of photoscreeners in screening at-risk amblyopia in Indian children. Indian J Public Health. 2022;66:171–5. 10.4103/ijph.ijph_1848_21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vidhya C. Efficacy of school screening by photoscreeners and prevalence of amblyopia in primary school childfren in Karnataka. EC Ophtalmol. 2020;11:01–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srivastava RM, Verma S, Gupta S, Kaur A, Awasthi S, Agrawal S. Reliability of smart phone photographs for school eye screening. Children. 2022;9:1519. 10.3390/children9101519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rono HK, Bastawrous A, Macleod D, Wanjala E, Di Tanna GL, Weiss HA, et al. Smartphone-based screening for visual impairment in Kenyan school children: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob health. 2018;6:e924–e32. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30244-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morjaria P, Bastawrous A, Murthy GVS, Evans J, Sagar MJ, Pallepogula DR, et al. Effectiveness of a novel mobile health (Peek) and education intervention on spectacle wear amongst children in India: results from a randomized superiority trial in India. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;28:100594. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]