Abstract

Objective

Given the rapid shift to in-home teleneuropsychology models, more research is needed to investigate the equivalence of non-facilitator models of teleneuropsychology delivery for people with younger onset dementia (YOD). This study aimed to determine whether equivalent performances were observed on neuropsychological measures administered in-person and via teleneuropsychology in a sample of people being investigated for YOD.

Method

Using a randomized counterbalanced cross-over design, 43 participants (Mage = 60.26, SDage = 7.19) with a possible or probable YOD diagnosis completed 14 neuropsychological tests in-person and via teleneuropsychology, with a 2-week interval. Repeated measures t-tests, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), and Bland Altman analyses were used to investigate equivalence across the administration conditions.

Results

No statistical differences were found between in-person and teleneuropsychology conditions, except for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Anxiety subtest. Small to negligible effect sizes were observed (ranging from .01 to .20). ICC estimates ranged from .71 to .97 across the neuropsychological measures. Bland Altman analyses revealed that the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Fourth Edition Block Design subtest had slightly better overall performance in the in-person condition and participants reported higher levels of anxiety symptoms during the teleneuropsychology condition; however, average anxiety symptoms remained within the clinically normal range. Participants reported a high level of acceptability for teleneuropsychology assessments.

Conclusions

These results suggest that performances are comparable between in-person and teleneuropsychology assessment modalities. Our findings support teleneuropsychology as a feasible alternative to in-person neuropsychological services for people under investigation of YOD, who face significant barriers in accessing timely diagnoses and treatment options.

Keywords: Teleneuropsychology, Younger onset dementia, Equivalence, Reliability, Telehealth, Dementia

INTRODUCTION

Younger onset dementia (YOD) is defined by the onset of cognitive symptoms before the age of 65 (Rossor et al., 2010) and includes people with dementia and neurocognitive disorders due to other conditions. People living with YOD often experience delays of up to 3 years or more before receiving a diagnosis (Loi et al., 2022a) due to the heterogeneity of symptom presentation (Loi et al., 2023). Neuropsychological assessments are considered the gold standard for early and accurate diagnosis in YOD (Loi et al., 2022b; State Government of Victoria, Department of Health, 2013). However, accessing neuropsychological services can be particularly challenging for individuals living in rural areas (Delagneau et al., 2021), or with community access difficulties (Bakker et al., 2014) and throughout the COVID-19 pandemic when in-person assessments were restricted (Cations et al., 2021). One potential solution to these service access issues is teleneuropsychology, which involves remotely providing neuropsychological assessments and services via videoconference technology.

Preliminary evidence supports the feasibility, acceptability, and psychometric equivalence of teleneuropsychology assessments. A limited number of studies have reported similar results on selected neuropsychological tests administered in-person and via teleneuropsychology in a small number of clinical populations including older-onset Alzheimer’s disease (Cullum et al., 2014), mild cognitive impairment (Cullum et al., 2014; Wadsworth et al., 2016, 2018), stroke (Chapman et al., 2021), early-stage psychosis (Stain et al., 2011), and epilepsy (Tailby et al., 2020). Guidelines have also been established to provide clinicians with clear instructions on how to use teleneuropsychology models for assessment in response to COVID-19 (Postal et al., 2021). A recent meta-analysis found no clear differences in performances across teleneuropsychology-delivered verbal tests compared to in-person administration (Brearly et al., 2017) and findings from a systematic review (Marra et al., 2020) demonstrated evidence of validity at a test level for tests of attention, working memory, language, and list learning memory tasks delivered via teleneuropsychology. Recent research has also demonstrated similar preliminary evidence of equivalence in hybrid teleneuropsychology models (Ceslis et al., 2022). Moreover, participants have expressed high levels of acceptability toward teleneuropsychology services (Appleman et al., 2021; Ceslis et al., 2022; Lawson et al., 2022; Parikh et al., 2013). Nevertheless, further research is necessary to demonstrate the reliability and validity of teleneuropsychology, as clinicians have identified a lack of empirical evidence as a significant barrier to teleneuropsychology adoption (Brown et al., 2023; Chapman et al., 2020; Hammers et al., 2020).

Although the aforementioned preliminary results are promising, some gaps in the literature remain. Firstly, very few studies have been conducted without a trained facilitator at the patient’s end of the assessment (Brearly et al., 2017). With the shift toward in-home models of teleneuropsychology delivery in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, more research is necessary to establish the equivalence between in-person and teleneuropsychology assessments without the support of an additional support person facilitating test administration. In addition, some studies have inferred a lack of between-group differences as equivalence between administration conditions. However, to establish equivalence, it is recommended that both between-group differences and reliability across administration methods be demonstrated (Bowden & Finch, 2017). Lastly, most research to date has focused on verbal tasks or tests that are easily adaptable for teleneuropsychology administration (Brearly et al., 2017). To our knowledge, only a few studies have included visual-based tasks (Chapman et al., 2021; Mahon et al., 2022) or traditional measures of executive functioning (Marra et al., 2020). This is particularly important given the increased rates of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and atypical Alzheimer’s disease presentations associated with YOD (Pijnenburg & Klaassen, 2021), requiring the need for a comprehensive cognitive assessment. Therefore, more evidence is required to guide future teleneuropsychology practice in determining which neuropsychological measures are comparable between in-person and videoconference assessments, and to identify tests that may not be suitable for remote delivery (Brearly et al., 2017). This information holds significant value in facilitating the routine implementation of teleneuropsychology assessments and follow up treatment services for the diagnosis and management of YOD in the future.

The primary aim of our study was to examine whether individual performances on neuropsychological tasks administered via teleneuropsychology were equivalent to those administered in-person, specifically among people undergoing investigation for YOD through a YOD service. The secondary aim was to evaluate participants’ acceptance of receiving neuropsychology assessment within a telehealth modality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

Consistent with previous teleneuropsychology studies (Brearly et al., 2017), this study utilized a randomized, counterbalanced cross-over design, where participants were randomly assigned to either an in-person or teleneuropsychology condition for their first test administration session, and then switched to the other condition for their second session. To reduce practice effects, alternate forms of the Hopkins Verbal Learning Task-Revised (HVLT-R) (Forms 1 and 2), Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) (alternative recall words), and Oral Symbol Digits Modalities Test (SDMT) (Forms 1 and 2) were counterbalanced across the administration conditions. In addition, a 2-week interval was provided between the two sessions to further mitigate the impact of practice effects. The research design outline is provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study design and recruitment process. Note. IP = in-person; TNP = teleneuropsychology; NP = neuropsychology.

Participants

Forty-three participants under investigation for YOD were recruited from a YOD service. Participants had to have the ability to provide informed consent (or have consent provided by a substitute decision-maker), be proficient in English, over 18 years of age, and have adequate self-reported hearing and eyesight. Participants with visual and/or hearing impairments were included if their impairments could be managed with aids. Exclusion criteria included symptom onset over 65 years of age; formal neuropsychological assessment within 3 months of participation; significant sensory, motor, intellectual, and/or severe cognitive impairment that prevented valid engagement with neuropsychological tasks; and a diagnosis of a neurological or psychological disorder other than YOD (e.g., stroke, schizophrenia). To determine the exclusion criteria for cognitive impairment, phone screening was conducted including a brief interview and administration of the Telephone Montreal Cognitive Assessment, in addition to consultation with the referring clinician and/or discussion within the research team. Fig. 1 displays the participant recruitment process. The study received ethical approval prior to commencement (HREC 59921).

Measures

A brief questionnaire was used to collect basic demographic and health-related information from participants. Demographic information included age, sex, education, occupational history, and current living circumstances (e.g., community-dwelling, residential living). Health-related information included working diagnosis, age of symptom onset, and presenting symptoms. Further diagnostic information was obtained from the participant’s electronic medical files or by contacting their treating clinician, if required.

Computer proficiency

The Computer Proficiency Questionnaire (CPQ) developed by Boot and coworkers (2015) is a validated measure of computer skills across six categories including computer basics, printing, communication, Internet usage, calendar, and entertainment software. Participants rated their ability to perform computer-related tasks on a 5-point rating scale, ranging from 1 (never tried) to 5 (very easily). Scores for each category were averaged and then summed to calculate an overall computer proficiency score ranging from 5 (low computer proficiency) to 30 (high computer proficiency).

Teleneuropsychology platform

The teleneuropsychology condition was conducted using Healthdirect video call (Healthdirect Australia, 2022), a secure videoconferencing service that is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations. Healthdirect is commonly used in healthcare services throughout Australia and is supported by the Australian Government of Health and Aged Care and the Victorian Department of Health (Healthdirect Australia, 2022). During the teleneuropsychology session, a Healthdirect video call was established between a Dell Latitude 7490 laptop and one Apple MacBook Pro laptop, which were set up in different rooms at the same location. The participant was seated in front of a laptop and viewed the researcher through the laptop’s inbuilt webcam. The researcher observed the participant through the inbuilt webcam pointed at the participant’s head and shoulders, and an external webcam attached to the top of the participant’s laptop aimed downward at the participant’s workspace. This allowed the researcher to observe the participant as they completed tasks.

Neuropsychological tests

The neuropsychological measures used in this study are listed in Table 1. The tests were selected to assess specific cognitive domains that are commonly evaluated in neuropsychological assessments for neurocognitive disorders and have been utilized in previous research investigating the feasibility and comparability of teleneuropsychology assessments. Further consultation with clinical neuropsychologists who specialize in YOD and teleneuropsychology helped refine the test list. All tests have acceptable psychometric properties (Strauss et al., 2006). Table 1 outlines the modifications made to neuropsychological measures to enable their delivery via teleneuropsychology. Modifications included sharing digital versions of neuropsychological test stimulus book pages using secure web-based platforms including Q-Global Pearson Inc. (2022) and RedShelf (2022), as well as providing test materials and response forms in specially colored envelopes located in the participant’s room. Q-Global is a secure web-based platform that facilitates onscreen test administration of subtests from the Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS), the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV), and the Wechsler Memory Scale—Fourth Edition (WMS-IV), as well as the Test of Premorbid Function (TOPF). RedShelf, a secure digital textbook platform, was used to administer the Boston Naming Test—Second Edition (BNT-2). All digital versions of the neuropsychological test stimulus book pages were shared securely between the researcher and participant’s laptops via a Healthdirect Video Call.

Table 1.

Neuropsychological tests and teleneuropsychology test modifications

| Measure | Modification for teleneuropsychology condition | Alternate form |

|---|---|---|

| Premorbid ability | ||

| Test of Premorbid Function (TOPF) (Wechsler, 2009a) | Digital TOPF word card screen shared with the participant; laptop cursor used for instructions | Not applicable |

| Cognitive screen | ||

| Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975) | Response forms in an envelope with the participant; external webcam used to observe the participant complete tasks | Alternate words |

| Attention and processing speed | ||

| Oral SDMT (Smith, 1973). | Response form in an envelope with the participant; external webcam used to observe the participant complete the task | Oral SDMT Form B |

| WAIS-IV—Digit Span (Wechsler, 2008) | None required | Not applicable |

| Language | ||

| Boston Naming Test—2nd Edition (BNT-2) (Kaplan et al., 2001). | Digital stimulus book screen shared with the participant | Not applicable |

| Visuospatial and visual perception skills | ||

| WAIS-IV—Block Design (Wechsler, 2008) | Digital stimulus book screen shared with the participant; block stimuli in a container in room with the participant; standard instructions provided including sample item; external webcam used to observe the participant complete the task | Not applicable |

| Simple Copy Test (Strauss et al., 2006) | Response form in an envelope with the participant; external webcam used to observe the participant complete the task | Not applicable |

| Learning and memory | ||

| HVLT-R (Brandt & Benedict, 2001) | None required | HVLT-R Form 2 |

| WMS-IV—Logical Memory (Wechsler, 2009b) | None required | Not applicable |

| WMS-IV—Visual Reproduction (Wechsler, 2009b) | Digital stimulus book screen shared with the participant; response form in an envelope with the participant; external webcam used to observe the participant complete the task | Not applicable |

| Executive function | ||

| WAIS-IV—Similarities (Wechsler, 2008) | None required | Not applicable |

| D-KEFS—Colour Word Interference (Delis et al., 2001) | Digital stimulus book screen shared with the participant; laptop cursor used for instructions | Not applicable |

| Trail Making Test (TMT) (Reitan & Wolfson, 1985) | Response forms in an envelope with the participant; external webcam used to observe the participant complete the task | Not applicable |

| Mood | ||

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983) | Response form in an envelope with the participant | Not applicable |

Note: SDMT = Symbol Digit Modalities Test; WAIS-IV = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Fourth Edition; HVLT-R = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test—Revised; WMS-IV = Wechsler Memory Scale—Fourth Edition; D-KEFS = Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System.

Acceptability of the test administration modalities

Following each test administration, participants completed a brief questionnaire that evaluated their acceptability of assessment session. The questionnaires were based on surveys used in previous research (Parikh et al., 2013). Both the in-person and teleneuropsychology versions of the questionnaire consisted of four items that assessed participants’ experiences during the session and their satisfaction. The teleneuropsychology version included eight additional items, covering factors such as comfort with technology, concerns with the teleneuropsychology session, and willingness to travel and wait for an in-person neuropsychology assessment compared to receiving a teleneuropsychology session.

Procedure

Participant’s eligibility for the study was assessed through an initial telephone screening call. Written consent was obtained from participants at the start of their first session and there were three instances where joint consent was obtained by care partners. Both the in-person and teleneuropsychology sessions were completed primarily at the participant’s residences. However, one participant was seen within a metropolitan hospital setting; another was seen at a rural-based Cognitive, Dementia, and Memory clinic; and one participant was seen in a secure room within a university setting. Demographic and health-related information, as well as the CPQ responses, were collected at the start of the first session. Standardized administration protocols were followed for the in-person administration condition. For the teleneuropsychology condition, test modifications were employed to administer the tests remotely (see Table 1), and participants were provided with a demonstration on how to use the laptop, the screen-sharing process, and instructions on how to use the colored envelopes at the beginning of the session. The neuropsychological tests were administered by a provisional psychologist, or a research assistant trained and supervised by a registered neuropsychologist, with the same researcher conducting both administration conditions for the same participant. After each condition, participants completed an online survey through Qualtrics (Qualtrics, 2022) to assess acceptability.

From July 2020, mandatory mask-wearing safety protocols were enforced throughout Victoria, Australia, due to COVID-19. As a result, the researcher and participants were required to wear a mask during the in-person administration condition, with 9 sessions conducted with the researcher wearing a mask throughout the entire session and 29 sessions conducted with the researcher removing their mask for specific verbal-based tasks (MMSE Registration, Repetition and Comprehension subtests, HVLT-R, WAIS-IV Digit Span and Similarities subtests, and WMS-IV Logical Memory subtest). In addition, five sessions were completed without the researcher wearing a mask before the COVID-19 safety mandates. Masks were not worn by the researcher or participants during the teleneuropsychology condition.

Data Analysis

Equivalence across in-person and teleneuropsychology administration modalities

Equivalence for the purposes of this study will refer to whether two assessments yield similar results (Walker & Nowacki, 2011). To assess equivalence, it is recommended to analyze the bias (mean difference) between two assessments and measure their reliability (Bowden & Finch, 2017). Following this approach and using statistical strategies commonly used in previous research (Chapman et al., 2021; Cullum et al., 2014), our study utilized three statistical analyses to determine equivalence between in-person and teleneuropsychology test performances. First, repeated measures t-tests were conducted for each neuropsychological measure to examine the level of statistical bias between scores obtained in-person versus using teleneuropsychology. Although some variables showed minor deviations from normality, transformations were not applied because repeated measures t-tests are robust with sample sizes above 30 (Field, 2013; Verma & Abdel-Salam, 2019). To calculate effect sizes, Cohen’s d was used as the standardized mean difference analysis (Field, 2013). Effect sizes were interpreted as small (d = .2), medium (d = .5), and large (d = .8) (Cohen, 1988, 1992).

Second, to assess reliability across administration conditions, single occasion, absolute agreement, two-way effects intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) (Koo & Li, 2016) using 95% confidence intervals were computed for each neuropsychological measure. Sample size requirements for ICC estimates were met based on requirements by Bujang and Baharum (2017). The normality of the data was checked both visually and quantitatively, and winsorization was applied to minimize the impact of outliers on variables (Field, 2013). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact of outliers on the data. Specifically, ICC and normality analyses were performed both before and after applying winsorization. The findings indicated that winsorizing the outliers did not significantly improve deviations from normality and did not meaningfully change ICC estimates in regard to classification bands. Given these results, and the importance of retaining data variation that reflects the natural differences in administration methods within the YOD clinical population, we chose not to winsorize the identified outliers. Interpretation of ICC estimates was based on guidelines provided by Koo and Li (2016), where estimates between 0 and 0.49 are considered poor, 0.50–0.74 moderate, 0.75–0.89 good, and 0.90–1 excellent.

Finally, we investigated the absolute agreement between in-person and teleneuropsychology methods using Bland Altman analyses and plots (Bland & Altman, 1990, 2010). Bland Altman plots illustrate the individual differences between in-person and teleneuropsychology administrations (e.g., an individual’s teleneuropsychology test score minus their in-person test score) plotted against their average performance on each neuropsychological task (Bland & Altman, 1990). This approach allows for the identification of systematic differences and random error across the administration conditions and facilitates visual interpretation of the variability in test performance (Van Stralen et al., 2008). In our study, positive bias scores indicated better performance in the teleneuropsychology administration condition, and negative bias scores indicated better performance in the in-person condition for most of the neuropsychological measures. Results for timed neuropsychological tasks have been inversed for ease of interpretation and consistency. Data management and analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 23. Raw scores for each neuropsychological task were used for data analyses.

Acceptability of the test administration modalities

Participants responded to questionnaire items accessing their acceptability of the administration conditions using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). To analyze these responses, counts and frequencies were used. To test for differences in acceptability between in-person and teleneuropsychology conditions, nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests and effect sizes were conducted.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Severe cognitive impairment was the most frequent reason for exclusion, as reported by the participants’ care partners, followed by diagnoses other than YOD. Table 2 presents the demographic information of the participants. The majority of the sample were in their early 60s, with almost half being female (48.8%). The most common queried YOD diagnoses were Alzheimer’s disease (32.6%) and Huntington’s disease (23.3%), followed by mild cognitive impairment (16.3%) and frontotemporal dementia (11.6%). Most participants were Australia-born, of whom 44.2% were rural dwellers throughout Victoria and border towns in New South Wales, Australia. The average number of days between administration sessions was 17.4 (SD = 7.0, range = 13–38). The degree of cognitive impairment was calculated by the number of cognitive domains in which each participant scored below 1.5 SD from the mean average performance. This method is commonly used in clinical neuropsychology practice (Lezak et al., 2012) and research (Winblad et al., 2004) to measure cognitive impairment. As displayed in Table 3, our results showed that majority of the sample (65.1%) scored below 1.5 SD across two or more cognitive domains, 16.3% scored below 1.5 SD in one domain, and 18.6% of participants did not score below 1.5 SD across any cognitive domains. No significant differences were found between mask-wearing and non-mask-wearing across verbal-based tasks (see results in Supplementary material online).

Table 2.

Participant demographic and health-related information, including queried YOD diagnosis, anxiety symptoms, and computer proficiency

| Participant characteristics | n (%) | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.26 (7.19) | 38–71 | |

| Sex (female) | 21 (48.8) | ||

| Education (years) | 13.71 (2.86) | 8–18 | |

| Country of birth | |||

| Australia | 32 (74.4) | ||

| New Zealand | 4 (9.3) | ||

| Papua New Guinea | 2 (4.7) | ||

| Burma | 1 (2.3) | ||

| India | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Italy | 1 (2.3) | ||

| South Africa | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Uruguay | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Queried YOD diagnosis | |||

| Alzheimer’s disease | 14 (32.6) | ||

| Huntington’s disease | 10 (23.3) | ||

| Mild cognitive impairment | 7 (16.3) | ||

| Frontotemporal dementia | 5 (11.6) | ||

| Parkinson’s disease | 3 (7.0) | ||

| Dementia with Lewy bodies | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Infection/neurosyphilis | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Metabolic disorder | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Head injury | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Age of symptom onset | 55.00 (7.54) | 33–66 | |

| CPQ | 21.86 (7.76) | 6–30 | |

| In-person HADS-A scores | |||

| Normal | 31 (72.1) | ||

| Mild | 5 (11.6) | ||

| Moderate | 7 (16.3) | ||

| Severe | 0 (0) | ||

| TeleNP HADS-A scores | |||

| Normal | 26 (60.5) | ||

| Mild | 6 (14.0) | ||

| Moderate | 10 (23.3) | ||

| Severe | 1 (2.2) | ||

| Geographical location of sessions | |||

| Metropolitan | 24 (55.8) | ||

| Rural | 19 (44.2) | ||

| Distance traveled (km) | 20,293.2 |

Note: CPQ = Computer Proficiency Questionnaire; HADS-A = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale—Anxiety subscale; HADS-D = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale—Depression subscale; teleNP = teleneuropsychology.

Table 3.

The degree of cognitive impairment across queried YOD diagnoses

| Queried YOD diagnosis | Multiple cognitive domains | 1 cognitive domain | No cognitive domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 28 | N = 7 | N = 8 | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 14 | ||

| Huntington’s disease | 6 | 4 | |

| Mild cognitive impairment | 5 | 2 | |

| Frontotemporal dementia | 5 | ||

| Parkinson’s disease | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Dementia with Lewy bodies | 1 | ||

| Infection/neurosyphilis | 1 | ||

| Metabolic disorder | 1 | ||

| Head injury | 1 |

Note: The degree of cognitive impairment was calculated by the number of cognitive domains that each participant fell below 1.5 SD from the mean average performance.

Comparison of In-Person and Teleneuropsychology Administration Modalities

Not all participants completed the entire neuropsychological test battery due to factors such as fatigue, time constraints, or meeting test discontinuation criteria. Descriptive data were computed for each neuropsychological task and are presented in Table 4. The means across the in-person and teleneuropsychology administration conditions were similar for most of the neuropsychological tasks. No significant differences and small to negligible effect sizes were found between the administration methods for most neuropsychological tasks except for the HADS-A subscale, t(41) = −2.16, p = .036, d = .20. On average, participants obtained higher HADS-A scores in teleneuropsychology administration condition (M = 6.72, SD = 4.74) compared to the in-person condition (M = 5.81, SD = 4.22). However, chi-square analyses revealed no statistically significant association between test administration mode (in-person vs. teleneuropsychology) and HADS-A severity,  2 = 2.00, df = 1, p = .16. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in HADS-A scores based on the order of administration conditions, whether the task was administered in-person, t(41) = 0.01, p = .99, or using teleneuropsychology, t(41) = 0.78, p = .44. These results indicate that the order of administration did not have a significant impact on anxiety scores.

2 = 2.00, df = 1, p = .16. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in HADS-A scores based on the order of administration conditions, whether the task was administered in-person, t(41) = 0.01, p = .99, or using teleneuropsychology, t(41) = 0.78, p = .44. These results indicate that the order of administration did not have a significant impact on anxiety scores.

Table 4.

Means, standard deviations, repeated measures t-test scores, intraclass correlation coefficients, and Bland Altman analyses for neuropsychological tests administered in-person and using teleneuropsychology

| In-person | Teleneuropsychology | ICC estimates | Bland Altman parameters | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | n | M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range | t | p | Cohen’s d | ICC | 95% CI | Bias | Lower LOA | Upper LOA |

| TOPF | 43 | 45.09 (16.43) | 14–69 | 44.02 (16.03) | 16–69 | 1.87 | .068 | .07 | .97 | 0.95–0.98 | −0.93 | −7.48 | 5.62 |

| MMSE | 43 | 25.70 (4.09) | 12–30 | 26.07 (3.47) | 16–30 | −1.31 | .198 | .10 | .88 | 0.69–0.93 | 0.37 | −3.27 | 4.01 |

| HVLT-R Total Recall | 43 | 17.86 (6.69) | 3–31 | 18.14 (6.84) | 3–32 | −0.42 | .680 | .04 | .79 | 0.65–0.88 | 0.28 | −8.34 | 8.90 |

| HVLT-R Delayed Recall | 43 | 5.60 (3.77) | 0–12 | 5.40 (3.74) | 0–12 | 0.83 | .412 | .05 | .90 | 0.83–0.95 | −0.23 | −2.90 | 2.44 |

| HVLT-R Discrimination Index | 43 | 6.84 (3.80) | 0–12 | 7.23 (3.29) | 0–12 | −1.01 | .320 | .11 | .74 | 0.57–0.85 | 0.30 | −4.35 | 4.83 |

| Oral SDMT | 38 | 35.37 (16.78) | 1–61 | 34.37 (16.73) | 5–61 | 0.97 | .337 | .06 | .93 | 0.87–0.96 | −0.58 | −9.75 | 8.59 |

| WAIS-IV Block Design | 42 | 32.02 (16.48) | 0–60 | 30.33 (15.88) | 0–59 | 1.70 | .097 | .10 | .91 | 0.85–0.96 | −2.07 | −12.44 | 8.30 |

| WAIS-IV Digit Span Forward | 43 | 9.00 (2.69) | 4–16 | 9.16 (2.82) | 4–15 | −0.69 | .497 | .06 | .84 | 0.73–0.91 | 0.16 | −2.25 | 2.57 |

| WAIS-IV Digit Span Backward | 43 | 6.98 (2.08) | 2–13 | 7.07 (2.06) | 3–13 | −0.39 | .702 | .04 | .71 | 0.52–0.83 | 0.23 | −1.53 | 1.99 |

| WAIS-IV Similarities | 39 | 21.54 (6.96) | 10–34 | 21.67 (6.24) | 7–34 | −0.22 | .825 | .02 | .86 | 0.74–0.92 | −0.03 | −5.52 | 5.40 |

| WMS-IV LM I | 41 | 21.44 (10.36) | 2–50 | 21.85 (10.50) | 2–40 | −0.47 | .643 | .04 | .85 | 0.74–0.92 | 0.41 | −10.72 | 11.54 |

| WMS-IV LM II | 41 | 16.00 (11.24) | 0–34 | 16.63 (11.54) | 0–37 | −0.70 | .486 | .05 | .87 | 0.78–0.93 | 0.63 | −10.68 | 11.94 |

| WMS-IV LM Recognition | 41 | 22.39 (3.62) | 12–29 | 22.07 (4.26) | 13–30 | 0.79 | .435 | .08 | .79 | 0.64–0.88 | −0.17 | −4.64 | 4.30 |

| WMS-IV VR I | 38 | 28.61 (10.06) | 1–43 | 27.79 (10.47) | 1–43 | 0.94 | .354 | .08 | .86 | 0.76–0.93 | −0.42 | −9.22 | 8.38 |

| WMS-IV VR II | 38 | 17.53 (13.05) | 0–40 | 17.16 (12.81) | 0–41 | 0.28 | .784 | .03 | .80 | 0.65–0.89 | −0.30 | −15.41 | 14.81 |

| WMS-IV VR Recognition | 38 | 4.45 (2.16) | 0–7 | 4.34 (2.28) | 0–7 | 0.53 | .600 | .05 | .85 | 0.73–0.91 | −0.11 | −2.53 | 2.29 |

| BNT-2 | 41 | 51.07 (9.99) | 13–60 | 51.54 (9.41) | 12–60 | −0.89 | .379 | .05 | .94 | 0.89–0.97 | 0.39 | −5.14 | 5.92 |

| D-KEFS CWI Colour Naming | 37 | 48.81 (19.98) | 27–90 | 50.32 (20.01) | 26–90 | −1.56 | .130 | .08 | .95 | 0.91–0.98 | −1.19 | −9.09 | 7.71 |

| D-KEFS CWI Word Reading | 38 | 33.76 (13.69) | 19–70 | 35.32 (14.64) | 19–90 | −1.46 | .153 | .11 | .89 | 0.80–0.94 | −1.16 | −9.65 | 7.33 |

| D-KEFS CWI Inhibition | 32 | 82.16 (31.32) | 42–180 | 82.03 (34.83) | 36–180 | 0.05 | .962 | .01 | .90 | 0.81–0.95 | −1.78 | −19.40 | 15.84 |

| D-KEFS CWI Switching | 25 | 86.36 (29.41) | 39–180 | 85.48 (30.82) | 34–180 | 0.27 | .789 | .03 | .86 | 0.71–0.94 | 1.72 | −13.69 | 17.13 |

| TMT-A | 42 | 64.24 (67.08) | 19–300 | 67.48 (67.00) | 17–300 | −0.62 | .541 | .05 | .87 | 0.76–0.93 | −1.46 | −27.43 | 24.51 |

| TMT-B | 32 | 125.06 (81.92) | 47–300 | 112.46 (63.87) | 38–300 | 1.39 | .173 | .17 | .75 | 0.55–0.87 | 5.69 | −42.62 | 54.00 |

| Simple Copy Test | 39 | 51.24 (4.89) | 39–57 | 51.67 (5.28) | 32–57 | −1.06 | .298 | .09 | .88 | 0.78–0.93 | 0.42 | −4.48 | 5.32 |

| HADS—Depression | 43 | 4.77 (4.17) | 0–16 | 5.35 (3.95) | 0–15 | −1.76 | .085 | .14 | .85 | 0.74–0.92 | 0.53 | −2.87 | 3.93 |

| HADS—Anxiety | 43 | 5.81 (4.22) | 0–15 | 6.72 (4.74) | 0–16 | −2.16 | .036 | .20 | .80 | 0.65–0.89 | 0.77 | −3.50 | 5.04 |

Note: ICC = intraclass correlation coefficients; CI = confidence intervals; LOA = limits of agreement; TOPF = Test of Premorbid Function; MMSE = Mini-Mental Status Examination; WAIS-IV = Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale—Fourth Edition; SDMT = Symbol Digit Modalities Test; HVLT-R = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test—Revised; WMS-IV = Wechsler Memory Scale—Fourth Edition; BNT-2 = Boston Naming Test—Second Edition; D-KEFS = Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System; TMT = Trail Making Test; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Table 4 presents the ICCs and 95% confidence intervals for each neuropsychological measure. ICCs ranged from 0.71 to 0.97, indicating moderate to excellent agreement across the test administration modalities. Neuropsychological measures that produced excellent ICCs included the TOPF (0.97), the D-KEFS Colour Word Interference Colour Naming subtest (0.95), the BNT-2 (0.94), and the Oral SDMT (0.93). In comparison, moderate ICCs were obtained for the WAIS-IV Digit Span Backward subtest (0.71) and HVLT-R Discrimination Index (0.74).

Table 4 displays the Bland Altman results. Most neuropsychological measures had bias values close to 0, except for the WAIS-IV Block Design subtest, which showed slightly better overall performance in the in-person condition. The Trail Making Test B subtest showed a high positive bias score, suggesting relatively better performance in the teleneuropsychology condition. Visual inspection of the Bland Altman plots showed relative symmetry in values above and below 0 for most neuropsychological measures, indicating no clear performance differences across in-person and teleneuropsychology administration methods. However, the WAIS-IV Block Design subtest showed a slightly higher proportion of negative values, suggesting somewhat better performance in the in-person condition, as shown in Fig. 2. Conversely, the HADS-A subtest had a significantly higher proportion of positive values, indicating a greater tendency for participants to report anxiety symptoms during the teleneuropsychology condition, as displayed in Fig. 3. Unequal spreads of variance across average performance scores were identified across five neuropsychological measures. Participants who performed slower on the timed D-KEFS Colour Word Interference subtests (Colour Naming, Word Reading, and Inhibition) and the Trail Making Test A and B subtests had more varied scores across administration conditions compared to those who were faster (please see Supplementary material online). These findings suggest that those who performed slower on the tasks had more inconsistent performances between the in-person and teleneuropsychology test administration conditions relative to those who performed well.

Fig. 2.

Bland Altman plot displaying the difference scores for WAIS-IV block design against average WAIS-IV block design scores. Note. Dashed line represents mean average difference score. Bolded lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Fig. 3.

Bland Altman plot displaying the difference scores for HADS-A against average HADS-A scores. Note. Dashed line represents mean average difference score. Bolded lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

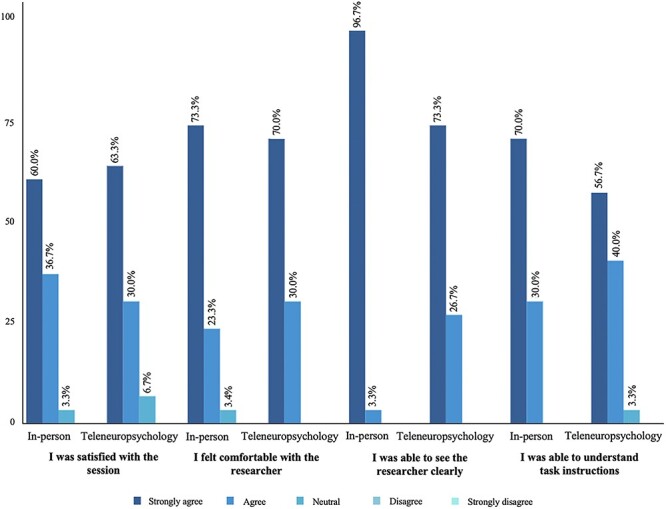

Participant Acceptability of the Test Administration Modalities

A total of 30 participants completed the in-person and teleneuropsychology acceptability questionnaires, with more than half of the sample (53.3%) having previous experiences with telehealth. Participant acceptability ratings for both modalities were very high, as shown in Fig. 4. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests indicated no significant differences and minimal effect sizes between the two administration modalities in terms of participant satisfaction (Z = 0.00, p = 1.00, r = .00), feeling comfortable with the researcher (Z = 0.00, p = 1.00, r = .00), and being able to understand task instructions (Z = −1.29, p = .20, r = −.24). However, a higher number of participants strongly agreed that they could see the researcher clearly during the in-person condition compared to the teleneuropsychology condition (Z = −2.33, p = .02, r = −.43).

Fig. 4.

Participant acceptability ratings for the in-person and teleneuropsychology conditions.

Table 5 presents participants’ responses to teleneuropsychology-specific questions and their preference for receiving neuropsychological assessments. The majority of participants had no preference for either in-person or teleneuropsychology modalities, and most agreed that they would recommend a teleneuropsychology session to others. Most participants felt comfortable using the technology and agreed that the teleneuropsychology condition was of equal quality to the in-person condition. Nonetheless, there was a level of diversity within the sample. For example, approximately one-third of participants indicated their willingness to wait for a short period or travel a short distance to undergo an in-person assessment; only 16.6% were willing to wait indefinitely and 6.6% were willing to travel indefinitely for an in-person assessment.

Table 5.

Teleneuropsychology-specific acceptability ratings and preference between in-person and teleneuropsychology methods

| Question | n (%) |

|---|---|

| I felt comfortable using the technology | |

| Strongly agree | 15 (50.0) |

| Agree | 14 (46.7) |

| Neutral | 1 (3.3) |

| Disagree | 0 (0) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0) |

| I was concerned before the teleneuropsychology session | |

| Strongly agree | 0 (0) |

| Agree | 9 (30.0) |

| Neutral | 7 (23.3) |

| Disagree | 9 (30.0) |

| Strongly disagree | 5 (16.7) |

| The quality of the teleneuropsychology session was equal to in-person | |

| Strongly agree | 8 (26.7) |

| Agree | 16 (53.3) |

| Neutral | 3 (10.0) |

| Disagree | 3 (10.0) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0) |

| I would recommend a teleneuropsychology assessment to others | |

| Strongly agree | 10 (33.3) |

| Agree | 17 (56.7) |

| Neutral | 3 (10.0) |

| Disagree | 0 (0) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0) |

| Willingness to wait for an in-person session rather than teleneuropsychology | |

| Less than 1 month | 9 (30.0) |

| 1–3 months | 8 (26.7) |

| I would wait as long as it takes to see someone in-person | 5 (16.6) |

| I would rather have a teleneuropsychology session | 8 (26.7) |

| Willingness to travel for an in-person session rather than teleneuropsychology | |

| Less than 1 hr | 11 (36.7) |

| 1–3 hr | 8 (26.7) |

| 3–6 hr | 1 (3.3) |

| I would travel as long as it takes to see someone in-person | 2 (6.6) |

| I would rather have a teleneuropsychology session | 8 (26.7) |

| Preferred condition | |

| In-person | 7 (23.3) |

| Teleneuropsychology | 3 (10.0) |

| No preference | 20 (66.7) |

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to determine whether teleneuropsychology-administered neuropsychological tasks yielded results comparable to those obtained through in-person administration for people under investigation for YOD. Furthermore, we sought to explore participants’ views toward using teleneuropsychology methods, as a means of receiving neuropsychological assessments. Overall, converging results from our equivalence analyses suggest that participants did not consistently perform better or worse in the in-person or teleneuropsychology administration conditions across most neuropsychological tasks. We also found high participant acceptability for teleneuropsychology, and no overall preference for in-person or teleneuropsychology methods.

Our study found that teleneuropsychology demonstrated a good level of equivalence for most of the neuropsychological measures, which is consistent with and expands upon previous teleneuropsychology equivalence research (Brearly et al., 2017; Chapman et al., 2021; Cullum et al., 2014). Our repeated measures analyses showed no significant differences between in-person and teleneuropsychology administration conditions for most tasks, except for the HADS-A measure. In addition, Bland Altman analyses revealed that participants reported higher anxiety symptoms during the teleneuropsychology condition compared to the in-person condition. Although this finding may reflect a true difference across the administration conditions, it is important to consider that the mean scores of the in-person and the teleneuropsychology HADS-A subscales were within the normal range (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983), and therefore may not have clinical significance, as both conditions did not exhibit significant levels of anxiety. In addition, no significant differences were found between anxiety severity across the test administration conditions. Although our sample displayed anxiety within the normal range, it is possible that the slight increase in anxiety during the teleneuropsychology condition could be attributed to the rapid transition to telehealth experienced by participants during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns and restrictions. At present, it is uncertain whether this heightened anxiety will persist post-pandemic. As such, future research is needed to investigate potential changes in anxiety within a post-pandemic context, particularly concerning teleneuropsychology assessments and services.

Our study found that the majority of neuropsychological measures had good to excellent ICC estimates, consistent with previous teleneuropsychology equivalence research (Brearly et al., 2017; Marra et al., 2020). However, the WAIS-IV Digit Span Backward and HVLT-R Discrimination Index subtests showed moderate ICC estimates. Notably, visual inspection of the Bland Altman plots showed no clear trend toward better or worse performance during the in-person or teleneuropsychology conditions for both tests. A possible explanation could be attributed to the tests’ stability over time, rather than a true difference between the administration conditions. For example, the ICC estimate for the WAIS-IV Digit Span Backwards subtest aligns with the WAIS-IV normative sample test–retest score (0.71) (Wechsler, 2008), whereas the observed ICC estimate for the HVLT-R Discrimination Index is higher than the established test–retest estimate of 0.40 (Benedict et al., 1998). Therefore, the moderate ICC values from the present study are consistent with, or are higher than, established test–retest reliability scores for these tests. Moreover, our Bland Altman analyses also showed that, for the D-KEFS Colour Word Interference Colour Naming, Word Reading, and Inhibition subtests, as well as the Trail Making Test A and B subtests, the spread of performance scores between the in-person and teleneuropsychology conditions was greater for individuals who performed poorer on the tests. Similar findings were reported in a previous study by Chapman and coworkers (2021), who suggested that this could be attributed to the diverse psychometric properties of neuropsychological measures for people with varying cognitive function. In addition, it is possible that there is less chance of variability across sessions for those who obtain lower scores than those who obtain higher scores across the Trail Making Test and D-KEFS Colour Word Interference tests.

Although the WAIS-IV Block Design subtest obtained an ICC estimate within the excellent range (Koo & Li, 2016), Bland Altman analyses revealed somewhat better performance during the in-person condition, which differs from previous research showing no evidence of systematic bias across administration conditions in healthy adults (Mahon et al., 2022). One possible explanation for this inconsistency is the inclusion of participants with moderate degrees of cognitive impairment. Although this can be considered a strength of the present study, deviating from the traditional method of having the WAIS-IV stimulus book on the same table as the blocks may have caused participants to work harder, and potentially slower, while looking up at the screen and back down at the blocks to complete the task. Therefore, clinicians may need to be cautious when deciding whether to administer this test using teleneuropsychology for people with more moderate degrees of cognitive impairment. Alternatively, a hybrid approach where patients are seen both in-person and remotely (Singh & Germine, 2021) may be considered. Another option includes administering a brief cognitive tool, such as the MMSE, the Neuropsychiatry Unit Cognitive Assessment Tool, or the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-III, to assess an individual’s level of cognitive functioning prior to selecting tasks to administer remotely. Furthermore, although preliminary evidence has shown the reliability of digitally screen shared stimulus books in healthy adults (Ceslis et al., 2022; Mahon et al., 2022), there is a need for additional studies to comprehensively compare the use of digital stimulus books compared to in-person traditional stimulus books across clinical populations.

Our results found that participants had high acceptability toward using teleneuropsychology as a practical method for receiving neuropsychological assessments, which reflects previous works with stroke survivors (Chapman et al., 2021) and older adults with varying degrees of cognitive change (Appleman et al., 2021; Dang et al., 2018; Parikh et al., 2013). This result is also not surprising given that the majority of our sample had used telehealth previously and the age range of participants included in the present study. Clinicians who have provided telehealth services to patients with YOD have reported the convenience of scheduling telehealth appointments around patient’s availability (Brown et al., 2023), which is especially beneficial for a younger onset group, many of whom are still employed and/or have younger families to attend to (Van Vliet et al., 2013). Our findings also found that a greater number of participants in the in-person condition strongly agreed that they could see the researcher compared to the teleneuropsychology condition. Although all participants in our sample either strongly agreed (73.3%) or agreed (26.7%) that they could see the researcher during the teleneuropsychology condition, this observation could be due to video clarity issues that have been previously reported as challenges to delivering teleneuropsychology (Fox-Fuller et al., 2022). A limitation of the present study was not providing participants with the opportunity to elaborate on their answers, which may have provided more insight into the variations in ratings. As such, future studies could qualitatively explore the factors that can affect participant’s ability to see during teleneuropsychology assessments, so that clinicians can better optimize visual clarity during sessions.

Almost all of the participants agreed that the quality of the teleneuropsychology condition was equal to the in-person condition and over half indicated no preference for in-person or teleneuropsychology methods in the future. However, our results also revealed a level of diversity regarding accessibility of teleneuropsychology and in-person services, with a small proportion of our sample preferring to wait longer and travel further to see a neuropsychologist in-person. This finding is not surprising given the geographical distribution of the participants, with just over half residing in metropolitan areas, where they have access to a wider range of healthcare alternatives compared to rural dwellers. In comparison, studies conducted among rural participants indicate that telehealth is highly acceptable, with convenience and comfort being major considerations (Sekhon et al., 2021). Overall, this finding suggests that patient preference for in-person or teleneuropsychology services varies depending on individual circumstances, highlighting the need for future research to investigate factors that may lead to more telehealth use within metropolitan and rural-based areas. Clinicians should also take into account patient preferences when considering the use of teleneuropsychology services for their patients.

There are a number of strengths of the current study. Notably, our results demonstrate that an equivalent teleneuropsychology assessment can be completed without the assistance of a trained facilitator at the participant end, providing further evidential support for in-home models of teleneuropsychology assessment delivery. In addition, the current study includes participants with varying degrees of cognitive impairment. It is acknowledged that eight participants in the sample were identified as having no cognitive impairment. This outcome is likely attributed to the method of assessing cognitive impairment, which compared participants’ performances relative to the mean average of their age group rather than their individual cognitive baseline. Consequently, this method may not have captured the subtle cognitive changes noted by their treating clinicians. In addition, it is important to highlight that the majority of participants had high levels of education, potentially leading to elevated individual cognitive baselines compared to individuals of the same age. As a result, these factors could have potentially contributed to the underestimation of cognitive impairment for some participants. Nonetheless, the majority of the sample displayed mild to moderate cognitive impairment. This extends upon previous teleneuropsychology equivalence research, which has typically focused on individuals living with mild cognitive impairment or those in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease to demonstrate that in-person and teleneuropsychology assessments are comparable. By including participants with more moderate stages of cognitive impairment, the current study provides clinicians with a better understanding of which individuals and tests may be suitable, or potentially unsuitable, for individuals with higher degrees of cognitive impairment.

The study has some limitations that should be noted. All sessions were conducted with the researcher and the participant at the same location, with the researcher usually traveling to participant’s place of residence. This was done to standardize the teleneuropsychology condition and avoid differences due to participant’s technology equipment. Moreover, having the test materials, for example, the WAIS-IV Block Design stimuli and record forms, on-site limits the practicality of this type of teleneuropsychology model, as it would require patients to travel to a clinic. As such, it does not directly reflect in-home teleneuropsychology assessments and the technology difficulties and logistic challenges experienced by clinicians. Therefore, more equivalence research is needed for in-home models of teleneuropsychology delivery to see if similar results are obtained. Nonetheless, the model of teleneuropsychology assessment adopted in the current study more closely resembles an in-clinic teleneuropsychology model, where patients can be seen virtually at a local clinic in a different room to the clinician (Postal et al., 2021), as well as a hub-and-spoke model. Hub-and-spoke models allow patients to be seen virtually at their local clinic while the clinician operates from a different location (Elrod & Fortenberry, 2017; Williams, 2021). It is worth nothing that the current study has demonstrated that teleneuropsychology assessments can be conducted without the need for a facilitator present throughout the entire session, eliminating the need for extra staff or resources to support the assessments. Moreover, these models offer several additional advantages, including a reduced risk of infection, increased clinician control over the testing environment and test selection during sessions, and the presence of in-clinic or spoke-site clinicians to address any technology-related disruptions (Postal et al., 2021).

We also acknowledge that our sample of participants were primarily Australia-born, fluent in English, with mild to moderate cognitive impairments, and included individuals with high computer literacy skills and prior telehealth experience. It is important for future research to explore whether teleneuropsychology is suitable for individuals with more severe cognitive impairment or behavioral change, as well as those with lower computer proficiency and greater language barriers, to determine whether equivalent results can be obtained in these populations. It is also important to note that the results from this study are limited to the specific clinical population of YOD, highlighting the need for future research to explore the equivalence of teleneuropsychology across other clinical populations. Lastly, the study did not investigate whether individual factors such as cognitive severity, mood, or age may explain the lower ICC estimates found in the present study. Future research is needed to determine whether lower reliability scores across tests is due to the psychometric properties of the tests or external factors such as participant characteristics.

In summary, the study demonstrated that teleneuropsychology assessment performances are comparable to in-person assessments for people with possible or probable YOD, and that remote assessments without a trained facilitator are feasible and reliable. In addition, the current study has shown that participants were generally very accepting of telehealth-administered neuropsychology assessments. Overall, the findings of this study support the use of remote delivery of neuropsychological assessments as a viable healthcare option. These findings offer the potential to expand healthcare options and increase accessibility for people under investigation for YOD, who experience significant barriers to accessing timely diagnoses and specialist treatment and care.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the participants who dedicated their time and effort to take part in the study. We also thank the Royal Melbourne Hospital Neuropsychiatry team and the Albury Cognitive Dementia and Memory Service for their support with recruitment.

Contributor Information

Aimee D Brown, Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health, School of Psychological Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia; Monash-Epworth Rehabilitation Research Centre, Melbourne, Australia.

Wendy Kelso, Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health, School of Psychological Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia; Neuropsychiatry, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Australia.

Dhamidhu Eratne, Neuropsychiatry, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Australia; Department of Psychiatry, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia.

Samantha M Loi, Neuropsychiatry, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Australia; Department of Psychiatry, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia.

Sarah Farrand, Neuropsychiatry, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Australia.

Patrick Summerell, Neuropsychiatry, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Australia.

Joanna Neath, Neuropsychiatry, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Australia.

Mark Walterfang, Neuropsychiatry, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Australia.

Dennis Velakoulis, Neuropsychiatry, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Australia.

Renerus J Stolwyk, Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health, School of Psychological Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia; Monash-Epworth Rehabilitation Research Centre, Melbourne, Australia.

FUNDING

This research was not supported by any specific grant from any funding agency.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

References

- Appleman, E. R., O’Connor, M. K., Boucher, S. J., Rostami, R., Sullivan, S. K., Migliorini, R., et al. (2021). Teleneuropsychology clinic development and patient satisfaction. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 35(4), 819–837. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1871515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, C., De Vugt, M. E., Van Vliet, D., Verhey, F. R. J., Pijnenburg, Y. A., Vernooij-Dassen, M. J. F. J., et al. (2014). The relationship between unmet care needs in young-onset dementia and the course of neuropsychiatric symptoms: A two-year follow-up study. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(12), 1991–2000. 10.1017/S1041610213001476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict, R. H. B., Schretlen, D., Groninger, L., & Brandt, J. (1998). Hopkins Verbal Learning Test—Revised: Normative data and analysis of inter-form and test-retest reliability. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 12(1), 43–55. 10.1076/clin.12.1.43.1726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (1990). A note on the use of the intraclass correlation coefficient in the evaluation of agreement between two methods of measurement. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 20(5), 337–340. 10.1016/0010-4825(90)90013-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (2010). Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(8), 931–936. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boot, W. R., Charness, N., Czaja, S. J., Sharit, J., Rogers, W. A., Fisk, A. D., et al. (2015). Computer proficiency questionnaire: Assessing low and high computer proficient seniors. The Gerontologist, 55(3), 404–411. 10.1093/geront/gnt117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, S. C., & Finch, S. (2017). When is a test reliable enough and why does it matter? In Bowden, S. C. (Ed.), Neuropsychological assessment in the age of evidence-based practice: Diagnostic and treatment evaluations (pp. 95–119). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, J., & Benedict, R. H. B. (2001). Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised. Odessa, TX: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Brearly, T. W., Shura, R. D., Martindale, S. L., Lazowski, R. A., Luxton, D. D., Shenal, B. V., et al. (2017). Neuropsychological test administration by videoconference: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychology Review, 27(2), 174–186. 10.1007/s11065-017-9349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. D., Kelso, W., Velakoulis, D., Farrand, S., & Stolwyk, R. J. (2023). Understanding clinician’s experiences with implementation of a younger onset dementia telehealth service. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 36(4), 295–308. 10.1177/08919887221141653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujang, M. A., & Baharum, N. (2017). A simplified guide to determination of sample size requirements for estimating the value of intraclass correlation coefficient: A review. Archives of Orofacial Science, 12(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cations, M., Day, S., Laver, K., Withall, A., & Draper, B. (2021). People with young-onset dementia and their families experience distinctive impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictions. International Psychogeriatrics, 33(8), 839–841. 10.1017/S1041610221000879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceslis, A., Mackenzie, L., & Robinson, G. A. (2022). Implementation of a hybrid teleneuropsychology method to assess middle aged and older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 37(8), 1644–1652. 10.1093/arclin/acac037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, J. E., Gardner, B., Ponsford, J., Cadilhac, D. A., & Stolwyk, R. J. (2021). Comparing performance across in-person and videoconference-based administrations of common neuropsychological measures in community-based survivors of stroke. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 27(7), 697–710. 10.1017/S1355617720001174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, J. E., Ponsford, J., Bagot, K. L., Cadilhac, D. A., Gardner, B., & Stolwyk, R. J. (2020). The use of videoconferencing in clinical neuropsychology practice: A mixed methods evaluation of neuropsychologists experiences and views. Australian Psychologist, 55(6), 618–633. 10.1111/ap.12471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullum, C. M., Hynan, L. S., Grosch, M., Parikh, M., & Weiner, M. F. (2014). Teleneuropsychology: Evidence for video teleconference-based neuropsychological assessment. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 20(10), 1028–1033. 10.1017/S1355617714000873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang, S., Gomez-Orozco, C. A., Van Zuilen, M. H., & Levis, S. (2018). Providing dementia consultations to veterans using clinical video telehealth: Results from a clinical demonstration project. Telemedicine and E-Health, 24(3), 203–209. 10.1089/tmj.2017.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delagneau, G., Bowden, S. C., van-der-EL, K., Bryce, S., Hamilton, M., Adams, S., et al. (2021). Perceived need for neuropsychological assessment according to geographic location: A survey of Australian youth mental health clinicians. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 10(2), 123–132. 10.1080/21622965.2019.1624170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis, D. C., Kaplan, E. F., & Kramer, J. H. (2001). Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Elrod, J. K., & Fortenberry, J. L. (2017). The hub-and-spoke organization design: An avenue for serving patients well. BMC Health Services Research, 17(S1), 457. 10.1186/s12913-017-2341-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using ISM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). London, England: SAGE Publications Ltd.. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox-Fuller, J. T., Rizer, S., Andersen, S. L., & Sunderaraman, P. (2022). Survey findings about the experiences, challenges, and practical advice/solutions regarding teleneuropsychological assessment in adults. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 37(2), 274–291. 10.1093/arclin/acab076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammers, D. B., Stolwyk, R., Harder, L., & Cullum, C. M. (2020). A survey of international clinical teleneuropsychology service provision prior to and in the context of COVID-19. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(7–8), 1267–1283. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1810323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthdirect Australia . (2022). [Computer Software]. Haymarkert, NSW: Healthdirect Australia Ltd. http://vcc.healthdirect.org.au.

- Kaplan, E. F., Goodglass, H., & Weintraub, S. (2001). The Boston Naming Test (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, D. W., Stolwyk, R. J., Ponsford, J. L., Baker, K. S., Tran, J., & Wong, D. (2022). Acceptability of telehealth in post-stroke memory rehabilitation: A qualitative analysis. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 32(1), 1–21. 10.1080/09602011.2020.1792318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak, M. D., Howieson, D. B., Bigler, D. B., & Tranel, D. (2012). Neuropsychological assessment (5th ed.). Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loi, S. M., Cations, M., & Velakoulis, D. (2023). Young-onset dementia diagnosis, management and care: A narrative review. Medical Journal of Australia, 218(4), 182–189. 10.5694/mja2.51849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loi, S. M., Goh, A. M. Y., Mocellin, R., Malpas, C. B., Parker, S., Eratne, D., et al. (2022a). Time to diagnosis in younger-onset dementia and the impact of a specialist diagnostic service. International Psychogeriatrics, 34(4), 367–375. 10.1017/S1041610220001489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loi, S. M., Walterfang, M., Kelso, W., Bevilacqua, J., Mocellin, R., & Velakoulis, D. (2022b). A description of the components of a specialist younger-onset dementia service: A potential model for a dementia-specific service for younger people. Australasian Psychiatry, 30(1), 37–40. 10.1177/1039856221992643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon, S., Webb, J., Snell, D., & Theadom, A. (2022). Feasibility of administering the WAIS-IV using a home-based telehealth videoconferencing model. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 36(3), 558–570. 10.1080/13854046.2021.1985172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra, D. E., Hamlet, K. M., Bauer, R. M., & Bowers, D. (2020). Validity of teleneuropsychology for older adults in response to COVID-19: A systematic and critical review. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(7–8), 1411–1452. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1769192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh, M., Grosch, M. C., Graham, L. L., Hynan, L. S., Weiner, M., Shore, J. H., et al. (2013). Consumer acceptability of brief videoconference-based neuropsychological assessment in older individuals with and without cognitive impairment. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 27(5), 808–817. 10.1080/13854046.2013.791723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson Inc . (2022). [Computer Software] Q-Global. Pearson clinical assessment. Sydney, Australia: Pearson Inc. https://qglobal.pearsonclinical.com/.

- Pijnenburg, Y. A. L., & Klaassen, C. (2021). Clinical presentation and differential diagnosis of dementia in younger people. In M. De Vugt & J. Carter (Eds.), Understanding young onset dementia: Evaluation, needs and care (1st ed., pp. 45–56). London and New York: Routledge Press. 10.4324/9781003099468. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Postal, K. S., Bilder, R. M., Lanca, M., Aase, D. M., Barisa, M., Holland, A. A., et al. (2021). InterOrganizational practice committee guidance/recommendation for models of care during the novel coronavirus pandemic. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 35(1), 81–98. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1801847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics XM. (2022). [Computer Software]. North Sydney, NSW: Qualtrics XM. https://www.qualtrics.com/au.

- RedShelf . (2022). [Computer Software] Boston Naming Test Second Edition Picture Cards. Chicago, IL: RedShelf. https://redshelf.com/.

- Reitan, R. M., & Wolfson, D. (1985). The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Therapy and clinical interpretation. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychological Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rossor, M. N., Fox, N. C., Mummery, C. J., Schott, J. M., & Warren, J. D. (2010). The diagnosis of young-onset dementia. Lancet Neurology, 9(8), 793–806. 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70159-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon, H., Sekhon, K., Launay, C., Afililo, M., Innocente, N., Vahia, I., et al. (2021). Telemedicine and the rural dementia population: A systematic review. Maturitas, 143, 105–114. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S., & Germine, L. (2021). Technology meets tradition: A hybrid model for implementing digital tools in neuropsychology. International Review of Psychiatry, 33(4), 382–393. 10.1080/09540261.2020.1835839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. (1973). Symbol Digit Modalities Test. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Stain, H. J., Payne, K., Thienel, R., Michie, P., Carr, V., & Kelly, B. (2011). The feasibility of videoconferencing for neuropsychological assessments of rural youth experiencing early psychosis. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 17(6), 328–331. 10.1258/jtt.2011.101015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State Government of Victoria, Department of Health . (2013). Cognitive dementia and memory service best practice guidelines. Victoria, Australia: State Government of Victoria. https://www.health.vic.gov.au/publications/cognitive-dementia-and-memory-service-best-practice-guidelines.

- Strauss, E., Sherman, E. M., & Spreen, O. (2006). A compendium of neuropsychological tests. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tailby, C., Collins, A. J., Vaughan, D. N., Abbott, D. F., O’Shea, M., Helmstaedter, C., et al. (2020). Teleneuropsychology in the time of COVID-19: The experience of The Australian Epilepsy Project. Seizure, 83, 89–97. 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Stralen, K. J., Jager, K. J., Zoccali, C., & Dekker, F. W. (2008). Agreement between methods. Kidney International, 74(9), 1116–1120. 10.1038/ki.2008.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet, D., De Vugt, M. E., Bakker, C., Pijnenburg, Y. A. L., Vernooij-Dassen, M. J. F. J., Koopmans, R. T. C. M., et al. (2013). Time to diagnosis in young-onset dementia as compared with late-onset dementia. Psychological Medicine, 43(2), 423–432. 10.1017/S0033291712001122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma, J. P., & Abdel-Salam, A. G. (Eds.). (2019). Assumptions in parametric tests. In J. P. Verma & A. G. Abdel-Salam, Testing statistical assumptions in research (pp. 65–140). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. 10.1002/9781119528388.ch4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth, H. E., Dhima, K., Womack, K. B., Hart, J., Weiner, M. F., Hynan, L. S., et al. (2018). Validity of teleneuropsychological assessment in older patients with cognitive disorders. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 33(8), 1040–1045. 10.1093/arclin/acx140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth, H. E., Galusha-Glasscock, J. M., Womack, K. B., Quiceno, M., Weiner, M. F., Hynan, L. S., et al. (2016). Remote neuropsychological assessment in rural American Indians with and without cognitive impairment. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 31(5), 420–425. 10.1093/arclin/acw030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, E., & Nowacki, A. S. (2011). Understanding equivalence and noninferiority testing. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(2), 192–196. 10.1007/s11606-010-1513-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. (2008). Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Fourth edition. Australian and New Zealand: Adapted Edition. Sydney, Australia: Pearson Clinical and Talent Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. (2009a). Advanced clinical solutions for WAIS-IV and WMS-IV. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Clinical and Talent Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. (2009b). Wechsler Memory Scale—Fourth edition. Australian and New Zealand: Language Adapted Edition. Sydney, Australia: Pearson Clinical and Talent Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C. (2021). Using the hub and spoke model of telemental health to expand the reach of community based care in the United States. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(1), 49–56. 10.1007/s10597-020-00675-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad, B., Palmer, K., Kivipelto, M., Jelic, V., Fratiglioni, L., Wahlund, L.-O., et al. (2004). Mild cognitive impairment - beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of Internal Medicine, 256(3), 240–246. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.