Abstract

Introduction

Colorectal cancer in children and adolescents is an exceptional condition. Its clinical symptoms are non-specific, leading to delayed diagnosis and poor prognosis.

Case presentation

The present article reports the case of a 15-year-old child followed for acute lymphoblastic leukemia with a history of a grandfather operated on and followed for colorectal cancer. The child was admitted to our department with an occlusive syndrome. Endoscopy and radiological findings suggested the diagnosis of colon adenocarcinoma (AC). The therapeutic decision was a segmental colectomy covering the right colonic angle and colostomy followed by chemotherapy.

Discussion

Colorectal cancer remains an exceptional pathology in children. They often include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and rectal discharge. Endoscopy is the key diagnostic test, enabling both distal and proximal lesions to be detected. Primary CA of the colon is rare in children, and even rarer as a second malignancy.

Conclusion

The clinical symptoms of colorectal adenocarcinoma in children are non-specific. These cancers are little-known in pediatrics, and are often diagnosed at an advanced stage.

Keywords: Adenocarcinoma, Children, Lymphoblastic leukemia, Heredity, Case report

Highlights

-

•

Colorectal cancer remains exceptionally rare in children, particularly among those with ALL, constituting approximately 1% of pediatric neoplasms.

-

•

Awareness and early intervention remain the key challenges for the early diagnosis and prognosis of CRC.

1. Introduction

Colon carcinoma is rare in the pediatric age group, comprising approximately 1 % of pediatric neoplasms [2]. This rarity is due to low awareness of the disease, which is often associated with genetic predisposition. In fact, young patients under chemotherapy are at high risk of developing colorectal cancer. It usually presents with an advanced-stage disease bearing a poor prognosis. In children, the presenting symptoms are nonspecific in 90% of cases [3]. Despite apparently radical surgery, carcinoma of the colon has a dismal prognosis. The present study aims to report the case of a 15-year-old child who presented with a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of the colon. This case report was written according to the SCARE criteria [1].

2. Observation

A 15-year-old child from a non-consanguineous marriage, followed for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (LAL) was treated and declared cured in 2015, six years after good local-regional control, the patient experienced a relapse of his disease for which he underwent chemotherapy following the “Marall protocol” with good progress. The last cycle was received one month ago. With a history of a grandfather operated on and followed for colorectal cancer.

The child history began three weeks previously with the onset of abdominal pain with colic-like symptoms accompanied by nausea, and episodes of vomiting, associated with bloody diarrhoea dating back 15 days, followed by constipation and then stopping of feces and gas three days ago, without fever or extra-digestive signs. Her general condition was altered, with asthenia, anorexia and weight loss of two kg in 15 days.

During the examination, the patient temperature was normal, also abdominal examination revealed a distended abdomen associated with generalized tenderness, without palpable mass.

Intestinal gurgling, tympany on palpation. No tumor syndrome. However, the rest of the examination was unremarkable.

The biological examination of the patient revealed: Complete blood count (CBC) normal: WBC 6420/mm3, PMN 4820/mm3, C-reactive protein (CRP) negative, normal serum electrolytes, ACE: positive at 7 ng/mL.

Abdominal X-Ray revealed the presence of multiple hydroaeric levels (Fig. 1). Computed Tomography showed the existence organic colonic occlusion upstream of a tumoral thickening of the right colonic angle.

Fig. 1.

The presence of multiple hydroaeric levels in abdominal X-rays.

Colonoscopy indicated the presence of four tumor-like proliferations localized in the transverse colon, which were histopathologically studied as low-grade (90%) and high-grade (10%) dysplastic tubular adenomas.

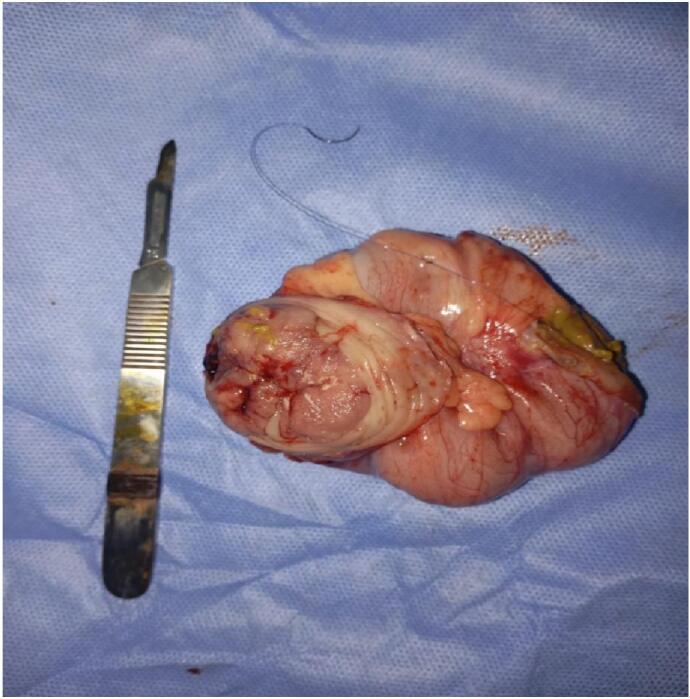

Laparotomy revealed the presence of a parietal tumor at the right colonic angle, obstructing the intestinal lumen at this level. The patient underwent a segmental colectomy covering the right colonic angle + colostomy (Fig. 2). Anatomopathological study favored a differentiated adenocarcinoma reaching the serosa (Pt3Nx), infiltrating the colonic wall. With healthy surgical resection margins (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

The specimen that is eliminated from right colon.

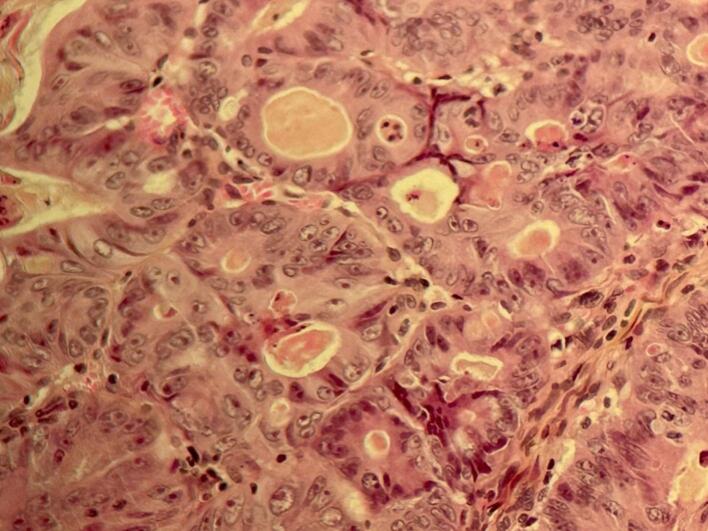

Fig. 3.

Pathologic and histologic examinations revealing an adenocarcinoma of the colon.

Post-operative follow-up was straightforward, and the patient was referred to pediatrics for his first chemotherapy session (folfox).

3. Discussion

Colorectal cancer is exceptional in children and adolescents. It accounts for 1% to 2% of all pediatric tumors. Its incidence has been estimated at 1/1,000,000 [4]. CRC occurs relatively more frequently in males than in female children with ratio of 2/1. It could develop as a secondary malignancy subsequent to ALL [5].

Indeed, Chantada et al reported 14 cases of colorectal cancer occurring before the age of 20, over a period of 13 years [6], while Vastyau et al reported 7 cases over a period of 16 years [7]. The transverse colon was the most frequent primary site of pediatric colorectal cancer.

Etiologically of the disease indicated that adults, adolescents and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease and hereditary disorders have an increased risk of developing colon cancer [8]. Our patient had a family history of colorectal cancer with a grandfather operated on and followed for colorectal cancer. Moreover, recent studies have demonstrated that treated patients for lymphomas before 25 years old have a high risk of developing a colorectal cancer [9], and that the etiological factors postulated for a primary malignancy and the effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy may also contribute to the development of the second malignancy [5].

The literature found on colon carcinoma in children under 17 is reviewed. This disease affects twice as many boys as girls. Abdominal pain, vomiting, constipation, weight loss, blood in the stool, abdominal distension and anorexia are common symptoms. The most common physical findings are the presence of an abdominal mass, abdominal distension and tenderness, anemia and dehydration. These signs and symptoms are similar to those observed in adults with this disease [10]. Our patient had a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of the colon, classified as T3. While the majority of the reports suggest that children present with more advanced disease than adults, with 80% to 90% of patients presenting with Dukes stage C/D or TNM stage III/IV disease [[11], [12]].

Once a diagnosis is suspected, evaluation usually includes abdominal X-rays, a CT scan and, finally, a colonoscopy. Colonoscopy is known to be the key diagnostic test for colorectal cancer. It enables distal and proximal lesions to be visualized, and biopsies to be taken [13].

Tumor markers can also be used to suspect the presence of colorectal cancer.

Many serum markers are associated with colorectal cancer, in particular antigène carcino-embryonnaire (CEA). However, serum markers, including CEA, have a low diagnostic capacity compared with radiological examination, due to low sensitivity (only 46%) and the possibility of false positives, even in other benign tumors. However, CEA levels above 5 ng/mL are more unfavorable than lower levels [14]. More than the half of CRC reported cases in children are poorly differentiated mucinous adenocarcinomas, and many are of the Signe ring cell type [15].

Following adult principles of treatment, the mainstay of therapy is complete surgical resection which without it the cure is impossible. Moreover, the treatment is essentially based on surgical resection, which must obey the rules of carcinological surgery in order to reduce the rate of local recurrence postoperatively [16]. However, complete carcinological excision is not always possible, given the often-advanced stage of the tumor at the time of diagnosis [6]. In these circumstances, and in the absence of metastases, pre-operative treatment with neo-adjuvant radiotherapy or radiochemotherapy could reduce tumor volume before proceeding with excision surgery [17]. In patients with unresectable tumors with intestinal obstruction, a permanent colostomy is performed.

The therapeutic decision for our patient, taken during a multidisciplinary staff meeting, was to carry out a surgical resection and a colostomy, to be followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. Following the surgery, the patient had a postoperative recovery that was mostly unremarkable, with the exception of postprocedural pain then referred to pediatrics for his first chemotherapy session. Furthermore, Colorectal cancer in children and adolescents has a poor prognosis. The 5-year survival rate is estimated at 18%, well below that observed in adults [18]. On the other hand, the survival of patients who underwent curative surgical excision was superior to that of patients who presented with an advanced unresectable form.

4. Conclusion

Colorectal cancer remains an exceptional pathology in children. When intestinal obstruction, refractory abdominal pain, weight loss, and anorexia symptoms occur in ALL chemotherapy children, it is necessary to consider ruling out the possibility of colorectal tumors.

Delayed diagnosis could possibly lead to progression in tumor stage and grade, with a significant impact on patient prognosis. Awareness and early intervention remain the key challenges for the early diagnosis and prognosis of CRC.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents/legal guardian for publication and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Ethical approval

At our institution, case reports or case series that are deemed not to constitute research do not require ethics approval. This policy is specific to [Mohammed VI University Hospital · Oujda. MAR].

Funding

We have any financial sources.

Author contribution

Dr. Siham ABBAOUI wrote the manuscript and analysed the literature research, Pr. Najlae ZAARI, Pr Abdelouhab AMMOR, Pr. Houssain BENHADDOU, supervised the writing of manuscript and performed the scientific validation. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Guarantor

Dr. Siham Abbaoui

Research registration number

N/A.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Maria N., Kerwan A., Franchi T., Agha R.A. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2023;109(5):1136. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guzmán S.B., García E.F.O., Rojas E.G.L., et al. Insights from a retrospective study: an understanding of pediatric colorectal carcinoma. Egypt Pediatr. Assoc. Gaz. 2024;72:4. doi: 10.1186/s43054-024-00246-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borger J.A., Barbosa J. Adenocarcinoma of the rectum in a 15-yearold. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1993;28:1592–1593. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(93)90109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prabakaran S., Senthilnathan S.V., et al. Aug 27, 2011. Adenocarcinoma of the Colon as a Second Malignancy in a Child. (PMID: 11527196, Epub) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chantada G.L., Perelli V.B., Lombardi M.G., et al. Colorectal carcinoma in children, adolescents, and young adults. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2005;27:39–41. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000149251.68562.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vastyan A.M., Walker J., Pinter A.B., et al. Colorectal carcinoma in children and adolescents-a report of seven cases. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2001;11:338–341. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernstein C.N., Blanchard J.F., Kliewer E., et al. Cancer risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Cancer. 2001;91:854–862. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010215)91:4<854::aid-cncr1073>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulaâmane Lamia, Tazi El Mehdi, et al. Maladie de hodgkin et cancer colique secondaire: à propos d un cas. PAMJ. 2011;9:25. doi: 10.4314/pamj.v9i1.71200. (Published online on 06 Jul 11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neal Middelkamp J., Haffner Heinz. Carcinoma of the colon in children. Pediatrics. 1963;32(4):558–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill D.A., Furman W.L., Billups C.A., et al. Colorectal carcinoma in childhood and adolescence: a clinicopathologic review. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25(36):5808–5814. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akinkuotu A.C., Maduekwe U.N., Hayes-Jordan A. Surgical outcomes and survival rates of colon cancer in children and young adults. Am. J. Surg. 2021;221(4):718–724. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandey A., Gangopadhyay A.N., Sharma S.P., Kumar V., Gupta D.K., Gopal S.C., Singh R.B. Pediatric carcinoma rectum- Varanasi experience. Indian J. Cancer. July–September 2008;45:119–122. doi: 10.4103/0019-509x.44068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung M.J., Chung S.M., Kim J.Y., et al. Prognostic significance of serum carcinoembryonic antigen normalization on survival in rectal cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiation. Cancer Res. Treat. 2013;45:186–192. doi: 10.4143/crt.2013.45.3.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skibber J.M., Minsky B.D., Hoff P.M. In: Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. DeVita V.T., Hellman S., Rosenberg S.A., editors. Lippincott Wilkins & Williams; Philadelphia: 2001. Cancer of the colon; pp. 1216–1271. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Endreseth B.H., Romundstad P., Myrvold H.E., et al. Rectal cancer in young patient. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2006;49:993–1001. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0558-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mremi A., Yahaya J.J. Advanced mucinous colorectal carcinoma in a 14-year old male child: a case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2020;04(030):201–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao B.N., Pratt C.B., Fleming I.D., et al. Colon carcinoma in children and adolescents. A review of 30 cases. Cancer. 1985;55:1322–1326. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850315)55:6<1322::aid-cncr2820550627>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]