Abstract

Assessment of critical quality attributes (CQAs) is an important aspect during the development of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). Attributes that affect either the target binding or Fc receptor engagement may have direct impacts on the drug safety and efficacy and thus are considered as CQAs. Native size exclusion chromatography (SEC)-based competitive binding assay has recently been reported and demonstrated significant benefits compared to conventional approaches for CQA identification, owing to its faster turn-around and higher multiplexity. Expanding on the similar concept, we report the development of a novel affinity-resolved size exclusion chromatography–mass spectrometry (AR-SEC-MS) method for rapid CQA evaluation in therapeutic mAbs. This method features wide applicability, fast turn-around, high multiplexity, and easy implementation. Using the well-studied Fc gamma receptor III-A (FcγRIIIa) and Fc interaction as a model system, the effectiveness of this method in studying the attribute-and-function relationship was demonstrated. Further, two case studies were detailed to showcase the application of this method in assessing CQAs related to antibody target binding, which included unusual N-linked glycosylation in a bispecific antibody and Met oxidation in a monospecific antibody, both occurring within the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs).

Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) often host a large number of post-translational modifications (PTMs), which can be either intended or unintended. These modifications, such as glycosylation, deamidation, and oxidation, are a result of various mechanisms during the mAb production, manufacturing, and storage.1−5 Of these modifications, some have little or no impact on product quality and thus are not considered as critical. Others may impair the efficacy or safety of the drug products and are therefore defined as critical quality attributes (CQAs).2,6,7 For a therapeutic mAb, the binding between the paratope from its complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) and the epitope from its therapeutic target, as well as the interactions between its fragment crystallizable (Fc) region and various Fc receptors, can largely impact its therapeutic functions. Therefore, modifications within these regions are potentially critical and worth thorough evaluations during drug development. For example, PTMs occurring within the mAb CDRs can often hinder its binding to the target by weakening or blocking the interactions between the epitope and the paratope. However, as not all residues in the CDRs participate in binding, PTMs occurring at nonbinding residues may not interfere with the target binding activity.8 In other cases, PTMs located outside of CDRs may indirectly influence target binding through allosteric effects. Therefore, it is important to assess the impact of individual modifications for CQA identification. While both empirical knowledge and computational modeling approaches9 provide valuable insights, it is essential to conduct experimental validation to confirm the impact of each modification on mAb function.

The conventional approach to assessing potential CQAs for their impacts on target and/or Fc receptor binding is a highly intricate process. This process involves the enrichment of the attribute-bearing variant followed by in vitro binding measurement or cell-based potency testing.10 The variant enrichment step is essential yet challenging in this workflow, as it demands the generation of samples containing individual variants with sufficient purity and quantity to allow unambiguous evaluation of binding affinity. To this end, various native liquid chromatography techniques,11 such as ion exchange chromatography (IEX),12,13 hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC),14,15 and size exclusion chromatography (SEC),16,17 are frequently employed to fractionate the desired attribute-bearing variants, owing to their excellent selectivity toward CDR modifications. This approach, however, is laborious and may be particularly challenging for low-abundance variants. As a result, application of specific stress conditions is sometimes required to artificially produce variants at elevated levels prior to fractionation, which further increases the complexity and the duration of the enrichment process. Finally, despite extensive fractionation efforts, it may be infeasible to enrich certain variants to necessary purity and quantity, making them unsuitable for this workflow. An emerging alternative for CQA identification without the need for variant enrichment is online affinity chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry analysis. In this method, mAb molecules undergo affinity-based separation on a column that is immobilized with its therapeutic target (e.g., an antigen) or various Fc receptors. Often, a pH gradient is employed to sequentially elute mAb variants based on their affinity to the immobilized ligands. Subsequent online mass spectrometry analysis allows direct confirmation of the mAb variants based on their signature mass changes. This approach has been successfully employed to assess critical attributes related to mAb binding with various Fc receptors. For example, the relationship between the mAb Fc N-linked glycosylation and its binding with FcγRIIIa has been extensively studied using online FcγRIIIa affinity LC-MS. These studies offered valuable insights into how Fc N-linked glycosylation can impact the antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC).18,19 Furthermore, the effects of both unintended Fc modifications (e.g., Met252 oxidation) and deliberate amino acid substitutions (e.g., M252Y/S254T/T256E) on antibody binding to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) have been evaluated by online FcRn affinity LC-MS,19,20 which highlighted their influence on mAb serum half-life. More recently, the antigen-based affinity chromatography mass spectrometry (AC-MS) approach has also been reported to assess attributes related to target binding.21 Despite the simplicity, the overall applicability of the AC-MS method is largely limited by the availability of the affinity columns. While it is possible to create custom-made affinity columns using various bonding chemistry, this process often comes with high costs and stability issues related to the reagents. In many cases, protein ligands must be engineered to enhance their stability for use in affinity chromatography applications. Combining with the modifications that occurred during the immobilization process, this could lead to inconsistent results when compared to a fully native ligand, potentially jeopardizing the biological relevance of the derived conclusions.19

Lately, the use of competitive binding to enrich mAb variants with diminished binding affinity for mass spectrometry (MS) detection has emerged as an attractive alternative to conventional CQA identification methods.22,23 By introducing insufficient amounts of antigen into mAb samples, mAb variants with impaired antigen binding ability are enriched in the unbound fraction. Following isolation of the bound and unbound fractions, comparative mass spectrometry analysis can provide facile assessment of the criticality of each attribute in a multiplexed fashion. In particular, SEC is known for its ability to preserve protein complexes that have relatively strong binding affinities, with KD values of 10 nM or lower.24 Therefore, it has been successfully implemented to separate the bound mAb-antigen complexes from the unbound mAb species based on their apparent differences in hydrodynamic radii.22,25 Recently, this SEC-based competitive binding strategy has been coupled online with reversed-phase LC-MS analysis in a 2D-LC format.26 This approach was successfully applied to evaluate the impact of Fab glycosylation on spike protein binding from four anti-SARS-COV-2 antibodies.

In this study, we developed an affinity-resolved SEC-MS (AR-SEC-MS) workflow that allows facile evaluation of antigen (Ag) and Fc receptor binding-related CQAs in therapeutic mAbs. In this workflow, a series of Ag and mAb (or Fc receptor and mAb) mixtures were prepared by introducing Ag to the corresponding mAb samples from insufficient to excess molar amounts. After separating the bound and unbound species in each mixture by SEC, online MS detection was utilized to characterize and compare the distribution of each mAb variant in both its bound and unbound forms. Notably, a denaturing solvent was introduced post-SEC separation to liberate the mAb species from the mAb-Ag complex to enable direct and unbiased intact mass monitoring. Finally, using the extracted ion chromatograms, the distributions of mAb variants in bound and unbound forms at varying mixing ratios can be used to assess their relative affinities to the target. The validity of this method was first demonstrated using a well-studied model system focusing on the interactions between Fc gamma receptor III-A (FcγRIIIa) and various Fc N-linked glycoforms. Further, two case studies were discussed in detail to showcase the utility of this new method in assessing the impact of CDR modifications on target binding.

Experimental Section

Materials

Deionized water was provided by a Milli-Q integral water purification system installed with a MilliPak Express 20 filter (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA). Ammonium acetate (LC/MS grade) and 2-propanol (IPA; HPLC grade) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). FabRICATOR was purchased from Genovis (Cambridge, MA). Invitrogen UltraPure 1 M Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.5, Pierce DTT (Dithiothreitol, No-Weigh Format), iodoacetamide (IAA), and acetonitrile (ACN; Optima LC/MS grade) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Formic acid (FA, 98–100%, Suprapur for trace metal analysis) was purchased from Millipore Sigma (Burlington, MA). Recombinant human FcγRIIIa (V158), mAb1, mAb2, mAb3, mAb4, Ag3 (ectodomain of Her2, target of mAb3), and Ag4 (C5, target of mAb4) were all produced in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells at Regeneron (Tarrytown, NY).

Sample Preparation

To prepare mixtures of FcγRIIIa and mAb samples, FcγRIIIa, mAb1, and mAb2 working solutions were first prepared at equal molar concentrations of 40 μM, followed by mixing of the corresponding working solutions at FcγRIIIa-to-Ab molar ratios of 1:4, 1:2, 1:1, 2:1, and 4:1. To prepare the antigen and antibody mixtures, mAb3 and mAb4 samples were first subjected to site-specific digestion with FabRICATOR (1 IUB milliunit per 1 μg of protein) in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5) at 37 °C for 1 h to generate the F(ab′)2 and Fc fragments. The digestion products of mAb3 were then mixed with Ag3 at Ag-to-Ab molar ratios of 1:2, 2:3, 1:1, 2:1, and 3:1. The digestion products of mAb4 were further subjected to limited reduction by incubating with 5 mM DTT in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5) at 37 °C for 30 min to selectively reduce interchain disulfide bonds, followed by alkylation with 20 mM IAA at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. The FabRICATOR-digested and partially reduced sample of mAb4 was then mixed with Ag4 at Ag-to-Fab molar ratios of 1:2, 1:1, 3:2, 2:1, and 5:2. The total protein concentrations for all mixtures were in the range of 1–5 mg/mL, and 2–10 μg of each mixture sample was subjected to analysis.

Affinity-Resolved SEC-MS

The mixtures containing pretreated mAb and its binding partner (e.g., FcγRIIIa or Ag) at varying molar ratios were subjected to postcolumn denaturation-assisted SEC-MS (SEC-PCD-MS) analysis. Native SEC chromatography was performed on an UltiMate 3000 UHPLC System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) equipped with an Acquity BEH200 SEC column (4.6 × 150 or 4.6 × 300 mm, 1.7 μm, 200 Å; Waters, Milford, MA) with the column compartment set to 30 °C. An isocratic flow of 150 mM ammonium acetate at 0.2 mL/min was applied to elute and separate the bound complexes from the unbound mAb or its binding partners in the mixtures. To enable postcolumn denaturation, a denaturing solvent consisting of 60% ACN, 36% water, and 4% FA was delivered by a secondary pump at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min and then mixed with the SEC eluent (1:1 mixing) using a T-mixer prior to MS detection. The combined flow (0.4 mL/min) was then split into a microflow (<10 μL/min) for nanoelectrospray ionization (NSI)-MS detection and a remaining high flow for UV detection (280 nm). A Thermo Orbitrap Exploris 480 Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a Microflow-Nanospray Electrospray Ionization (MnESI) Source and a Microfabricated Monolithic Multinozzle (M3) emitter (Newomics, Berkeley, CA) was used for MS analysis. A detailed experimental setup and instrument parameters can be found in previous publications.27,28

Data Analysis

Integration of the XIC peak from the SEC-PCD-MS analysis was performed using Thermo Fisher Xcalibur software (version 3.0). Intact mass spectra from SEC-PCD-MS analysis were deconvoluted using Intact Mass software from Protein Metrics. Details of deconvolution parameters are described in the Supporting Information (Table S1).

Results and Discussion

Affinity-Resolved SEC-MS Workflow

To assess the impact of mAb attributes on target or Fc receptor binding affinity, protein mixtures containing the mAb and its binding partner (e.g., antigen or Fc receptors) were mixed at varying ratios and subjected to SEC-PCD-MS analysis (Figure 1). Using a previously reported native LC-MS platform,27 the bound complex and unbound mAb species were first separated by SEC based on their differences in hydrodynamic radii. Subsequently, a denaturing solvent was introduced post column to instantly dissociate the noncovalently bound complex into its constituent mAb and its binding partner prior to MS detection. The denaturing solvent composition was previously optimized to disrupt many known noncovalent interactions (e.g., HC–LC and HC–HC interactions in partially reduced Ab and Ag-Ab complexes) instantaneously upon postcolumn mixing while maintaining the dissociated protein components in the solution phase for MS detection.28 The adoption of a multinozzle emitter for NSI on this platform was also key to accommodate the increased flow rate after solvent mixing and provide sensitive MS measurement. Next, online MS analysis provided direct identification of mAb proteoforms (e.g., both unmodified and variant forms) based on accurate mass measurement. Finally, using an extracted ion chromatogram (XIC), the distribution of each identified mAb proteoform originating from the complex and unbound forms can be readily reconstructed and visualized (Figure 1). Under competitive binding conditions, it is anticipated that mAb proteoforms with higher binding affinities (e.g., unmodified mAb) will be preferentially enriched into the complex form, while the proteoforms with lower binding affinities (e.g., mAb variants) will be enriched into the unbound form. By analyzing a series of mixtures at varying mixing ratios, the binding affinities of different mAb variants relative to the unmodified mAb can be simultaneously compared. It is worth noting that with this SEC-PCD-MS workflow, it is only necessary to monitor the mAb species by MS, allowing the often highly heterogeneous antigens or receptors to be excluded from the analysis. In addition, the employed SEC-PCD-MS method produces native-like spectra for mAb molecules,28 which greatly simplifies the data interpretation, due to the separation of mAb signal from its binding partners in the m/z space (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

General workflow for affinity-resolved SEC-MS.

To facilitate data interpretation, three different mAb treatment procedures were performed prior to the mixing with the binding partners. As illustrated in Figure S1a, when studying the mAb interaction with Fc receptors, the mAb sample was directly mixed with various Fc receptors at different molar ratios without any treatment. In the study of mAb interaction with target antigen, two distinctive sample treatment strategies were adopted for bispecific antibody (bsAb) (Figure S1b) and monospecific antibody (msAb) (Figure S1c). First, since the antigen binding only involves the Fab domains of an antibody, both bsAb and msAb molecules were subjected to FabRICATOR (IdeS) treatment to release the F(ab)′2 fragments prior to the mixing with the target antigen. This treatment significantly improved the MS detection sensitivity by reducing the size of the analytes (from intact mAb to F(ab)′2 fragment) and removing mass heterogeneities introduced by Fc N-linked glycans. This is particularly crucial for the successful detection of mAb variants that are present in low abundance. For bsAb, each of its two Fab arms can be individually assessed using the corresponding antigen. Due to a simple 1:1 binding stoichiometry between each Fab arm and its target (in most cases), the IdeS-digested sample was directly mixed with the antigen to prepare the mixtures. In contrast, due to the bivalency, msAb has the potential to form a variety of complexes in the presence of its antigen. These can range from 1:1 and 1:2 complexes to larger heterogeneous complexes with different stoichiometries through interactions with multivalent antigens. This can lead to complicated separation profiles during SEC analysis, posing challenges in interpreting the results. To simplify the binding stoichiometry, the IdeS-digested msAb sample was further subjected to reduction under native conditions to selectively disrupt the interchain disulfide bonds and further convert F(ab)′2 fragments into Fab fragments, which consist of noncovalently interacting Fd and LC. The newly generated free thiols were also capped by an alkylation reaction to prevent disulfide bond reformation. It is worth noting that this IdeS and limited reduction strategy is implemented as it can be generally applied to both human IgG1 and IgG4 subclasses, the two most popular formats as protein therapeutics. However, other enzymes may also be utilized (e.g., FabDELLO for generating IgG1 Fab without hinge reduction). After these treatments, the sample was mixed with the antigen to form a desired 1:1 Fab-Ag complex and subjected to SEC-PCD-MS analysis. Notably, the noncovalent Fab fragments can be well preserved during SEC separation. However, under PCD conditions, they will be further dissociated into Fd and LC for MS detection due to the absence of interchain disulfide bonds. Consequently, further details about the location of the attributes can also be obtained using this sample preparation approach. Last, by reducing the size of the analytes from intact mAb to F(ab)′2 or Fab fragments, SEC separation of the complex and unbound species can also be improved due to the superior performance of SEC in resolving smaller analytes. This is particularly important in studying mAb binding with smaller targets, where the size differences between the complex and unbound mAb may be less significant.

Study of the Influence of Fc N-Linked Glycosylation on FcγRIIIa Binding by Affinity-Resolved SEC-MS

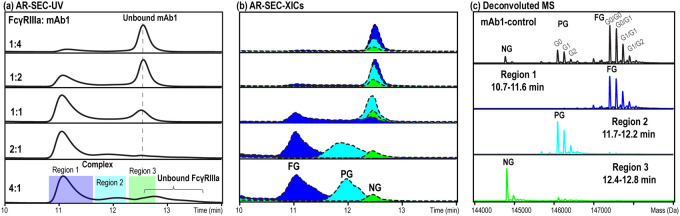

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the affinity-resolved SEC-MS method for studying the attribute-and-function relationship, the interaction between FcγRIIIa and two IgG1 mAbs was subjected to the test. FcγRIIIa, a well-studied Fc receptor with a medium affinity to the Fc domain of IgG molecules (KD ≈ 10–400 nM),29 is associated with the antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) pathway.30−32 It binds to the antibody Fc region in a 1:1 stoichiometry,33,34 and the binding affinity is largely influenced by the composition of the antibody Fc N-glycans at the conserved N-glycosylation site N297 (EU numbering system)35 from the CH2 domain. In the first study, an IgG1 molecule (mAb1), which was primarily produced as afucosylated antibody (e.g., G0, G1, and G2), was subjected to affinity-resolved SEC-MS analysis with an in-house produced FcγRIIIa (ectodomain, M.W. = 38–43 kDa, Figure S2a). Briefly, FcγRIIIa and mAb1 were mixed at various ratios (1:4, 1:2, 1:1, 2:1, and 4:1) and the formed mAb-FcγRIIIa complex was separated from the unbound FcγRIIIa or the unbound mAb on an SEC column, followed by online PCD-MS detection (Figure 2). Upon mixing, a discrete SEC peak (10.7–11.6 min, Figure 2a) eluting earlier than both the unbound FcγRIIIa and mAb was observed, indicating the formation of a stable mAb-FcγRIIIa complex under SEC conditions. This aligns well with the enhanced binding affinity between FcγRIIIa and an afucosylated IgG1.36−38 As the ratio of FcγRIIIa to mAb1 was increased from insufficient levels (1:4 and 1:2) to excess levels (2:1 and 4:1), a corresponding increase in the complex formation and a decrease in unbound mAb abundance were observed (Figure 2a). Using online PCD-MS detection, the distributions of mAb1 glycoforms in the complex and unbound forms can be readily visualized through XICs. For example, by generating the XICs of the nonglycosylated (NG), partially glycosylated (PG), and fully glycosylated (FG) mAb species in each mixture sample, it was found that the FG species (Figure 2b, blue trace) displayed the highest binding affinity to the receptor and was transitioned first from the unbound form to the complex form. The PG species (Figure 2b, cyan trace) only exhibited receptor binding in samples with excess levels of receptors (i.e., 2:1 and 4:1 mixtures), after the FG species were completely transitioned into the complex form. In contrast, the NG species (Figure 2b, green trace) exhibited no binding to the receptor and remained in the unbound form, even in the presence of excess amounts of FcγRIIIa in the 2:1 and 4:1 mixtures. Interestingly, despite the similar size, the complex formed by FcγRIIIa and PG species eluted at a significantly later retention time window (12.4–12.8 min) compared to the complex formed by FcγRIIIa and FG species (11.7–12.2 min). This is likely attributed to the weaker binding affinity between the PG species and FcγRIIIa. As a result, when tested under non-equilibrium conditions, the complex underwent on-column dissociation and the resulting constituents moved at a slower pace than the original complex due to their smaller sizes. This observation also reconciles with a previous report39 that described dissociation of weakly bound complexes during SEC separation, leading to prolonged retention time. Notably, the apparent elution profile differences of mAb variants, as a result of variable on-column dissociation, provided an additional dimension to compare and rank their relative binding affinities. Finally, using the 4:1 mixture sample as an example, the three major glycoforms (NG: 12.4–12.8 min; PG: 11.7–12.2 min; FG: 10.7–11.6 min) of mAb1 were effectively separated on SEC in an affinity-resolved manner prior to PCD-MS detection (Figure 2c). The relative affinity of each glycoform to FcγRIIIa binding, as determined in this study, aligned well with previous reports using other techniques.19,40,41

Figure 2.

Affinity-resolved SEC-MS to study the FcγRIIIa (ectodomain, 38–43 kDa) binding of mAb1. (a) SEC-UV traces from analyses of FcγRIIIa and mAb1 mixtures prepared at ratios from the insufficient level (1:4) to excess level (4:1) of FcγRIIIa. (b) XICs of fully glycosylated (FG), partially glycosylated (PG), and nonglycosylated (NG) mAb1 from SEC-PCD-MS analyses of each mixture sample. The XICs were reconstructed using the most abundant charge state of each species. (c) Deconvoluted mass spectrum of mAb1 from native SEC-MS analysis in the absence of FcγRIIIa (1st panel, black); deconvoluted mass spectra of mAb1 species eluting between 10.7 and 11.6 min (2nd panel, blue), 11.7 and 12.2 min (3rd panel, cyan), and 12.4 and 12.8 min (4th panel, green) from SEC-PCD-MS analysis of the 4:1 mixture sample. The corresponding raw mass spectra are shown in Figure S3.

In addition to glycan occupancy (e.g., macroheterogeneity), the affinity of IgG1 antibodies to FcγRIIIa also depends on the specific type of N-glycan (e.g., microheterogeneity) at position N297. In particular, it was previously reported that IgG1 species, which either lack core fucosylation or contain more terminal galactoses on the Fc N-glycan, show increased affinity toward FcγRIIIa.19,36,38,42 To further demonstrate the ability of the affinity-resolved SEC-MS method in revealing the impact of N-glycan microheterogeneity on antibodies’ affinity toward FcγRIIIa, another IgG1 molecule (mAb2) was tested. Unlike mAb1, mAb2 was produced without tampering the fucosylation pathway so that it contains primarily core-fucosylated and biantennary N-glycans (e.g., G0F, G1F, and G2F), with relatively low levels of afucosylated forms (e.g., G0, G1, and G2). Similarly, mixtures of FcγRIIIa and mAb2 prepared at different ratios (1:4, 1:2, 1:1, and 2:1) were separated on SEC, followed by online PCD-MS analysis (Figure 3). Contrary to the mAb1 example where discrete complex peaks were observed, the complexes formed by mAb2 and FcγRIIIa were eluted within a broad (10.7–12.3 min) and undefined peak. This difference is presumably attributed to the increased on-column dissociation of the mAb2-FcγRIIIa complexes due to the overall reduced affinity of core-fucosylated mAb toward FcγRIIIa. To compare the FcγRIIIa binding affinity, the distribution profiles of mAb glycoforms were reconstructed using the corresponding XICs from the PCD-MS analysis, and they are shown in Figure 3b. When the amount of FcγRIIIa was very limited (in a 1:4 mixture), the singly core-fucosylated glycoforms (G0/GxF, x = 0, 1, and 2; Figure 3b, yellow, orange, and red traces) were the first to transition into the complex form, indicating that they were preferentially bound to FcγRIIIa. When additional FcγRIIIa was introduced (in 1:2, 1:1, and 2:1 mixtures), the remaining doubly core-fucosylated glycoforms (GxF/GxF, x = 0, 1, and 2; Figure 3b, blue, cyan, and green traces) also started to form complexes with FcγRIIIa. In addition, the complexes formed by FcγRIIIa and doubly core-fucosylated glycoforms (GxF/GxF) eluted significantly later (11.4–12.3 min) compared to the complexes formed by FcγRIIIa and singly core-fucosylated glycoforms (G0/GxF; 10.7–11.4 min). This is likely attributed to the increased on-column dissociation between FcγRIIIa and doubly core-fucosylated glycoforms due to reduced binding affinity. Further, by examining the retention order of the three individual glycoforms within each group (e.g., singly core-fucosylated and doubly core-fucosylated), it was also concluded that glycoforms with higher levels of terminal galactose demonstrated higher binding affinities toward FcγRIIIa. This was evidenced by the earlier retention time of their corresponding complexes (or increased stability) during SEC separation compared to those with lower levels of terminal galactose (e.g., elution order: G0/G2F > G0/G1F > G0/G0F; G1F/G1F > G0F/G1F > G0F/G0F). Notably, the achieved resolution of various glycoforms by this AR-SEC-MS method is based on their on-column dissociation onset points due to different affinities, which is different from that previously reported by msACE-MS (mobility shift affinity capillary electrophoresis coupled to MS), where the glycoforms with different FcγRIIIa affinities were resolved via interaction-specific binding equilibrium.43 These findings are highly consistent with previous studies highlighting the critical role of Fc N-glycans in influencing FcγRIIIa binding. Finally, using the 2:1 sample as an example, the deconvoluted mass spectra of mAb2 glycoforms eluting from 10.7 to 11.4 min and from 11.4 to 12.3 min were generated to illustrate the affinity-resolved separation of singly and doubly core-fucosylated species (Figure 3c, middle and bottom panels). It is important to note that several singly core-fucosylated glycoforms (e.g., G0/G1F, G0/G2F, and G1/G2F) can only be confidently identified by this affinity-resolved SEC-MS method. In contrast, they were not discerned by regular SEC-MS analysis due to their low abundances and similar masses to other more prevalent, doubly core-fucosylated forms (e.g., G0/G1F and G0F/G0F differ by only 16 Da) (Figure 3c, top panel). Therefore, besides studying the attribute-and-function relationship, this affinity-resolved SEC-MS method may also be a valuable addition to conventional intact mass techniques for mAb heterogeneity characterization, owing to its unique affinity-based separation mechanism.

Figure 3.

Affinity-resolved SEC-MS analysis to study the FcγRIIIa binding of mAb2. (a) SEC-UV traces from analyses of FcγRIIIa and mAb2 mixtures prepared at ratios from the insufficient level (1:4) to excess level (2:1) of FcγRIIIa. (b) XICs of mAb2 containing G0/G0F (yellow), G0/G1F (orange), G0/G2F (red), G0F/G0F (blue), G0F/G1F (cyan), and G1F/G1F (or G0F/G2F, green) glycoforms from SEC-PCD-MS analyses of each mixture sample. The XICs were constructed using the most abundant charge state of each species. (c) Deconvoluted mass spectrum of mAb2 from native SEC-MS analysis in the absence of FcγRIIIa (1st panel); deconvoluted mass spectra of mAb2 species eluting between 10.7 and 11.4 min (2nd panel) and 11.4 and 12.3 min (3rd panel) from SEC-PCD-MS analysis of the 2:1 mixture sample.

Collectively, the findings from these two studies were highly consistent with those previously documented, highlighting the crucial roles of both macro- and microheterogeneity of Fc N-glycosylation in FcγRIIIa binding. Importantly, compared to other established workflows, such as AC-MS21 and ACE-MS,44 this new method provided a few unique advantages. For example, unlike AC-MS, the described workflow does not depend on the availability of specific affinity columns. Therefore, it can be readily expanded to study other Fc receptor interactions (e.g., FcγRI, FcγRII, FcγRIIIb, and neonatal Fc receptor) using soluble ligands that are readily accessible. Furthermore, by eliminating the need for ligand engineering (often required for stability concern) and immobilization, the use of more native-like ligands could generate results with potentially improved biological relevance. On the other hand, while both employing soluble ligands, AR-SEC-MS may compare favorably to ACE-MS, thanks to the unique PCD capability to completely liberate the mAb variants from the bound complexes.

Evaluation of CDR N-Linked Glycosylation in a Bispecific Antibody by Affinity-Resolved SEC-MS

Next, the affinity-resolved SEC-MS method was used to evaluate the impact of CDR N-linked glycosylation on target binding in a bsAb molecule (mAb3). MAb3 consists of two identical light chains (LC) and two different heavy chains (HC and HC*). This molecule contains a notable level of N-linked glycosylation at the Asn55 residue within the HC CDR2, which is known to reduce the binding affinity to its corresponding target (referred to as Ag3) based on surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based measurement (data not shown). Prior to mixing with Ag3 (ectodomain, M.W. = 86–92 kDa, Figure S2b), the mAb3 sample was first digested by IdeS and subjected to native SEC-MS analysis to verify the digestion products. As expected, the digested sample was shown to consist of F(ab′)2 and Fc (consists of two noncovalently interacting Fc/2) fragments that were chromatographically resolved based on their size differences (Figure 4a). Interestingly, F(ab′)2 variants with an additional N-linked glycan (mainly G2FS and G2FS2; Figure 4a, inset) were identified in a distinct SEC peak eluting before the unmodified F(ab′)2 species. This change in SEC retention behavior is likely due to the altered protein surface characteristics (e.g., charge and/or hydrophobicity) as a result of the CDR N-glycosylation and subsequent changes in secondary interaction with the SEC column. To assess the impact of this CDR N-glycosylation on target binding, the IdeS-digested mAb3 samples were mixed with Ag3 at various Ag-to-Ab ratios (1:2, 2:3, 1:1, 2:1, and 3:1) and then subjected to SEC-PCD-MS analysis. As expected, the SEC-UV traces of the mixture samples all displayed a distinct F(ab′)2-Ag3 complex peak (5.1 min) that was well separated from the unbound species (Figure 4b). As more Ag3 were introduced, there was an apparent decrease in the peak intensity of the unbound F(ab′)2 species (6.1–7.1 min) relative to the peak intensity of the Fc fragments (7.2–7.4 min). In particular, when the Ag-to-Ab ratio rose above 1:1, no discernible UV peak corresponding to either unbound F(ab′)2 species was detected, suggesting that both unmodified and CDR N-glycosylated F(ab′)2 species were bound to Ag3 under these experimental conditions. This observation indicated that this CDR N-glycosylation did not entirely abolish its target binding affinity, where the complex could still be formed and preserved under SEC conditions. However, close examination of the two unbound F(ab′)2 UV peaks revealed a notably faster reduction of the unmodified species compared to the N-glycosylated species with the addition of Ag3 (Figure 4b). This difference suggested that the N-glycosylated species may have a lower target binding affinity than the unmodified species. Alternatively, this difference in binding affinity can be more clearly demonstrated by generating the XICs of the unmodified (Figure 4c) and N-glycosylated F(ab′)2 species (Figure 4d) from the PCD-MS analyses followed by comparison of their corresponding distributions in the complex and unbound forms in each mixture sample. It is evident that when Ag3 was at insufficient levels (e.g., 1:2 or 2:3), only the unmodified F(ab′)2 exhibited binding to Ag3, while the N-glycosylated F(ab′)2 species were entirely present in the unbound form (Figure 4c,d, blue and cyan traces). At the Ag-to-Ab ratio of 1:1, virtually all the unmodified F(ab′)2 species were transitioned into the complex form (Figure 4c, green trace). Meanwhile, the N-glycosylated F(ab′)2 species started to show binding to Ag3 and were detected in both the complex and unbound forms in the same sample (Figure 4d, green trace). When the Ag-to-Ab ratio rose above 1:1, the N-glycosylated F(ab′)2 species exhibited further transition into the complex form and was nearly depleted from the unbound form in the 3:1 mixture (Figure 4d, orange and red traces). This observation was also evidenced by the mass spectra of F(ab′)2 species from the complex peak, in which N-glycosylated F(ab′)2 species started to appear in the 1:1 sample (Figure S4). Additionally, as demonstrated by the XICs, the complexes formed by Ag3 and the unmodified F(ab′)2 were eluted as a discrete peak (4.9–5.2 min; Figure 4c) in all mixture samples, suggesting that the complexes were stable during SEC separation. In contrast, XICs of the N-glycosylated F(ab′)2 species from the 1:1, 2:1, and 3:1 mixtures all displayed two broad peaks in the complex-eluting region (4.9–6.3 min; Figure 4d, green, orange, and red traces). This likely indicated the on-column dissociation of the complexes formed by Ag3 and the N-glycosylated F(ab′)2 during SEC separation due to a decrease in binding affinity. Noteworthily, these observations agreed well with a separate SPR-based affinity measurement performed using SEC-enriched samples, which detected a 2-fold increase in KD from the unmodified (KD = 4 nM) to the CDR N-glycosylated mAb3 species (KD = 8 nM). This consistency further validated the effectiveness of the affinity-resolved SEC-MS method in studying the attribute-and-function relationship. Notably, although quantitative comparison of KD values cannot be achieved through AR-SEC-MS analysis due to the non-equilibrium conditions present during SEC separation, it is plausible to assume that complexes that could not form or underwent on-column dissociation may bear KD values of ∼10 nM or higher.

Figure 4.

(a) Native SEC-UV/MS analysis of mAb3 after IdeS digestion illustrating the chromatographic separation of the unmodified and CDR N-glycosylated F(ab′)2 species and their corresponding deconvoluted mass spectra (inset). (b) SEC-UV traces from affinity-resolved SEC-MS analysis using Ag3 (ectodomain of Her2, M.W. = 86–92 kDa) and F(ab′)2 mixtures prepared at ratios from the insufficient level (1:2) to excess level (3:1) of Ag3. (c) XICs of the unmodified F(ab′)2 species from SEC-PCD-MS analyses of each mixture sample showing its distribution in the complex and unbound forms. (d) XICs of the N-glycosylated F(ab′)2 (with G2FS2) from SEC-PCD-MS analyses of each mixture sample showing its distribution in the complex and unbound forms. The XICs were reconstructed using the most abundant charge state of each species.

Evaluation of CDR Oxidation in a Monospecific Antibody by Affinity-Resolved SEC-MS

To showcase its applicability in msAbs, the affinity-resolved SEC-MS method was employed to evaluate the impact of CDR oxidation (HC Met105) on target binding in a msAb (mAb4). As previously discussed, msAb contains two identical Fab arms that can potentially lead to the formation of a variety of complexes in the presence of its antigen, thus complicating the result interpretation. Therefore, they are pretreated to generate monovalent half molecules prior to affinity-resolved SEC-MS analysis. In this example, mAb4 was first treated with IdeS digestion followed by limited reduction and alkylation to produce a mixture containing Fab and Fc fragments. Given that the specific reduction of mAb interchain disulfide bonds is well known to pose minimal impact on its conformation,45 this treatment should not alter its target binding properties. Subsequent SEC-MS analysis showed that the Fab and Fc species were not chromatographically separated due to their similar sizes but readily differentiable by intact mass measurements (Figure 5a). Additionally, PCD-MS was also applied to interrogate the interchain reduction products, demonstrating complete interchain reduction and the absence of PTMs introduced by this treatment (Figure S5). Next, the pretreated mAb4 sample was mixed with its target antigen (referred to as Ag4, M.W. = 192–198 kDa, Figure S2c) at Ag-to-Fab ratios of 1:2, 1:1, 3:2, 2:1, and 5:2, followed by SEC-PCD-MS analysis. As demonstrated by the SEC-UV chromatograms (Figure 5b), as more Ag4 was introduced into the mixtures, there was a notable increase in the peak intensity of the complex species (Fab-Ag4, 5.1–5.5 min) and a corresponding decrease in the peak intensity of the unbound species (unbound Fab and Fc, 7.2–7.5 min). Additionally, an apparent UV peak corresponding to the free Ag4 (5.5–5.8 min) was detected in the 5:2 mixture sample, suggesting that Ag4 was in excess. Interestingly, in this sample, a significant UV peak corresponding to the unbound species remained, which was mostly attributed to the Fc fragments. In this instance, due to the coelution of Fab and Fc, it is infeasible to rely on SEC-UV to detect potential Fab variants that had lost target binding affinity. Instead, PCD-MS data could be utilized to generate the XICs that are specific to both the unmodified and oxidized Fab species, allowing a comparison of their distributions in the complex and unbound forms. Notably, due to the absence of the interchain disulfide bond, the noncovalently associated Fab fragments were further dissociated into Fd and LC under PCD conditions prior to MS detection. In this case, the unmodified Fab was dissociated and detected as LC and Fd, whereas the oxidized Fab was dissociated and detected as LC and oxidized Fd. Hence, by generating the XICs of the Fd and its oxidized form from PCD-MS analysis, the distributions of both the unmodified and oxidized Fab species can be monitored separately. Meanwhile, the XICs of the LC could be used to represent the overall distribution of all Fab species. As shown in Figure 5c, the XICs of the LC showed a progressive shift in peak intensity from the unbound peak to the complex peak, as more Ag4 was introduced. However, the 5:2 mixture sample displayed an LC distribution highly similar to that of the 2:1 mixture sample, with both showing a notable unbound peak. Given the excess levels of Ag4 in these two samples, this observation implied the presence of a Fab variant with diminished target binding affinity. Consistently, the XICs of the unmodified Fd showed a similar transition in peak intensity from the unbound peak to the complex peak as the Ag-to-Fab ratio increased from 1:2 to 2:1. In addition, the unbound peak was not detectable from the XIC of the unmodified Fd in the 5:2 mixture sample (Figure 5d), suggesting that all the unmodified Fab species were in the complex form when Ag4 was in excess. In contrast, the XICs of the oxidized Fd consistently exhibited only a single unbound peak in all the mixture samples (Figure 5e), even with excess levels of Ag4. In addition, the mass spectra of Fd and LC species from both the complex and unbound peaks also showed the progressive enrichment of the oxidized Fd species in the unbound peak with the addition of Ag4 (Figures S6 and S7). This observation suggested that this CDR Met oxidation considerably reduced, or even abolished, the target binding affinity of mAb4. The findings from this affinity-resolved SEC-MS analysis also aligned well with SPR-based affinity measurements, which reported a KD of 0.3 nM (to Ag4) for the unmodified mAb4 but no binding for the Met105 oxidized form (data not shown). It is important to note that for SPR-based affinity measurements, the oxidized variants were prepared through forced oxidation using peroxide-based reagents. This process often generates very high levels of oxidation on multiple Met sites, which may not accurately represent the variants found in a typical mAb product. Therefore, this affinity-resolved SEC-MS method is a valuable addition to conventional approaches, enabling direct assessment of potential CQAs from unenriched and undisturbed samples.

Figure 5.

(a) Native SEC-UV/MS analysis of mAb4 after IdeS digestion, limited reduction, and alkylation showing the elution profiles of Fab and Fc by UV (solid line) and XICs (dotted and filled lines) and their corresponding deconvoluted mass spectra (inset). (b) SEC-UV traces from affinity-resolved SEC-MS analysis using Ag4 (soluble C5, M.W. = 192–198 kDa) and Fab mixtures prepared at ratios from the insufficient level (1:2) to excess level (5:2) of Ag4. (c) XICs of LC from SEC-PCD-MS analyses of each mixture sample showing its distribution in the complex and unbound forms. (d) XICs of the unmodified Fd from SEC-PCD-MS analyses of each mixture sample showing its distribution in the complex and unbound forms. (e) XICs of the oxidized Fd from SEC-PCD-MS analyses of each mixture sample showing a single unbound peak. All XICs were generated using the most abundant charge state of each corresponding species.

Conclusions

Therapeutic mAbs often host attributes that need to be studied to understand their impact on target binding and Fc receptor engagement. This is traditionally performed in a low-throughput and laborious fashion by attribute enrichment followed by binding affinity measurements. Recently, SEC-based competitive binding has been reported as a successful approach to isolating and identifying mAb variants with compromised target binding affinity. Leveraging the same concept, here, we report the development of an affinity-resolved SEC-MS method that facilitates fast and direct assessment of mAb attributes for their impact on target or Fc receptor binding. By generating varying ratios of Ag and mAb (or Fc receptor and mAb) mixtures and examining them using SEC-PCD-MS, mAb variants with reduced binding affinity can be readily revealed. In particular, utilizing XICs from the SEC-PCD-MS analysis, the distribution of mAb variants in the complex and unbound forms can be visualized, allowing a direct comparison of their binding affinity. To demonstrate the effectiveness of this newly developed approach, the binding between FcγRIIIa and two different IgG1 molecules was studied. The findings from these analyses were highly consistent with those previously documented, highlighting the crucial roles of both macro- and microheterogeneity of Fc N-glycosylation in FcγRIIIa binding. Additionally, two different case studies, including CDR N-glycosylation in a bsAb and CDR Met oxidation in a msAb, were showcased in detail to illustrate the application in assessing CQAs associated with mAb target binding. Collectively, it was demonstrated that this newly established affinity-resolved SEC-MS method provides a valuable addition to conventional approaches for studying the mAb attribute-and-function relationship. Comparing to previously reported offline SEC-enrichment approaches,22,23,25 this online approach offers unique advantages in throughput and sensitivity. However, it is worth noting that the utility of this current method may be limited for unknown attributes, as the intact mass approach does not provide residue-level identification. Therefore, this method is primarily used to evaluate known attributes that have been previously identified (e.g., CDR PTMs identified by peptide mapping analysis). Additionally, while attributes associated with notable mass shifts can be effectively interrogated, those with minimal or no mass shifts (e.g., Asn deamidation and Asp isomerization) present a notably greater challenge. Although not covered in the present study, both these limitations may be addressed by enhancing this method with top-down and/or middle-down techniques. Finally, as this method does not require prior attribute enrichment through fractionation or forced degradation, it is ideally suited for CQA evaluation during early-stage drug developability assessment, where a fast turn-around is highly desired. With the valuable information provided, subsequent variant enrichment and activity assays may be implemented to further validate the findings.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. The authors would like to thank Steven Henderson, Nathaniel Kosyak, Youmi Moon, Yue Fu, Kathir Muthusamy, Ram Vanam, Justin Heftel, and Dorothy Kim from Protein Biochemistry Group for generating enriched mAb variant material and performing SPR-based affinity measurements.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.4c00660.

Parameters used to generate deconvoluted mass spectra using Intact Mass software; sample treatment strategies for studying mAb-Fc receptor, bsAb-Ag, and msAb-Ag binding; mass spectra of FcγRIIIa (ecto), Ag3 (etco), and Ag4; raw mass spectra of mAb1 from AR-SEC-MS analysis; raw mass spectra of F(ab′)2 species of mAb3 in the complex peak from AR-SEC-MS analysis; raw mass spectra of Fab and Fc of mAb4 under native and PCD conditions; raw mass spectra of Fd and LC of mAb4 from AR-SEC-MS analysis; deconvoluted mass spectra of Fd of mAb4 in the complex form and in the unbound form from AR-SEC-MS analysis (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Y.Y., T.X., X.H., W.P., S.W., and N.L. are full-time employees and shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ambrogelly A.; Gozo S.; Katiyar A.; Dellatore S.; Kune Y.; Bhat R.; Sun J.; Li N.; Wang D.; Nowak C.; et al. Analytical comparability study of recombinant monoclonal antibody therapeutics. MAbs 2018, 10 (4), 513–538. 10.1080/19420862.2018.1438797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferis R. Posttranslational Modifications and the Immunogenicity of Biotherapeutics. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 2016, 5358272 10.1155/2016/5358272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins N.; Murphy L.; Tyther R. Post-translational modifications of recombinant proteins: significance for biopharmaceuticals. Mol. Biotechnol 2008, 39 (2), 113–118. 10.1007/s12033-008-9049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Chung C. Y.; Chough S.; Betenbaugh M. J. Antibody glycoengineering strategies in mammalian cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2018, 115 (6), 1378–1393. 10.1002/bit.26567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Singh S.; Zeng D. L.; King K.; Nema S. Antibody structure, instability, and formulation. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 96 (1), 1–26. 10.1002/jps.20727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hmiel L. K.; Brorson K. A.; Boyne M. T. 2nd. Post-translational structural modifications of immunoglobulin G and their effect on biological activity. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2015, 407 (1), 79–94. 10.1007/s00216-014-8108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer B.; Schuster M.; Jungbauer A.; Lingg N. Microheterogeneity of Recombinant Antibodies: Analytics and Functional Impact. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13 (1), 1700476 10.1002/biot.201700476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y.; Wei H.; Fu Y.; Jusuf S.; Zeng M.; Ludwig R.; Krystek S. R. Jr.; Chen G.; Tao L.; Das T. K. Isomerization and Oxidation in the Complementarity-Determining Regions of a Monoclonal Antibody: A Study of the Modification-Structure-Function Correlations by Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88 (4), 2041–2050. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X.; Wang W.; Tesar D.; Wei B.; Eschelbach J.; Kelley R. F.; Jiang G. An Approach to Bioactivity Assessment for Critical Quality Attribute Identification Based on Antibody-Antigen Complex Structure. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 110 (4), 1652–1660. 10.1016/j.xphs.2020.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geigert J.The challenge of CMC regulatory compliance for biopharmaceuticals and other biologics; Springer, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alhazmi H. A.; Albratty M. Analytical Techniques for the Characterization and Quantification of Monoclonal Antibodies. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16 (2), 291–320. 10.3390/ph16020291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y.; Liu A. P.; Wang S.; Daly T. J.; Li N. Ultrasensitive Characterization of Charge Heterogeneity of Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibodies Using Strong Cation Exchange Chromatography Coupled to Native Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90 (21), 13013–13020. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b03773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A. P.; Yan Y.; Wang S.; Li N. Coupling Anion Exchange Chromatography with Native Mass Spectrometry for Charge Heterogeneity Characterization of Monoclonal Antibodies. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94 (16), 6355–6362. 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c00707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete S.; Veuthey J. L.; Beck A.; Guillarme D. Hydrophobic interaction chromatography for the characterization of monoclonal antibodies and related products. J. Pharm. Biomed Anal 2016, 130, 3–18. 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y.; Xing T.; Wang S.; Daly T. J.; Li N. Online coupling of analytical hydrophobic interaction chromatography with native mass spectrometry for the characterization of monoclonal antibodies and related products. J. Pharm. Biomed Anal 2020, 186, 113313 10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukrer B.; Filipe V.; van Duijn E.; Kasper P. T.; Vreeken R. J.; Heck A. J.; Jiskoot W. Mass spectrometric analysis of intact human monoclonal antibody aggregates fractionated by size-exclusion chromatography. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27 (10), 2197–2204. 10.1007/s11095-010-0224-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyon A.; Beck A.; Veuthey J. L.; Guillarme D.; Fekete S. Comprehensive study on the effects of sodium and potassium additives in size exclusion chromatographic separations of protein biopharmaceuticals. J. Pharm. Biomed Anal 2017, 144, 242–251. 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodall D. W.; Dillon T. M.; Kalenian K.; Padaki R.; Kuhns S.; Semin D. J.; Bondarenko P. V. Non-targeted characterization of attributes affecting antibody-FcgammaRIIIa V158 (CD16a) binding via online affinity chromatography-mass spectrometry. MAbs 2022, 14 (1), 2004982 10.1080/19420862.2021.2004982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotham V. C.; Liu A. P.; Wang S.; Li N. A generic platform to couple affinity chromatography with native mass spectrometry for the analysis of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. J. Pharm. Biomed Anal 2023, 228, 115337 10.1016/j.jpba.2023.115337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahoual R.; Heidenreich A. K.; Somsen G. W.; Bulau P.; Reusch D.; Wuhrer M.; Haberger M. Detailed Characterization of Monoclonal Antibody Receptor Interaction Using Affinity Liquid Chromatography Hyphenated to Native Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89 (10), 5404–5412. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippold S.; Hook M.; Spick C.; Knaupp A.; Whang K.; Ruperti F.; Cadang L.; Andersen N.; Vogt A.; Grote M.; et al. CD3 Target Affinity Chromatography Mass Spectrometry as a New Tool for Function-Structure Characterization of T-Cell Engaging Bispecific Antibody Proteoforms and Product-Related Variants. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95 (4), 2260–2268. 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c03827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi R. L.; Xiao G.; Dillon T. M.; McAuley A.; Ricci M. S.; Bondarenko P. V. Identification of critical chemical modifications by size exclusion chromatography of stressed antibody-target complexes with competitive binding. MAbs 2021, 13 (1), 1887612 10.1080/19420862.2021.1887612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Yan Y.; Wang S.; Li N. A competitive binding-mass spectrometry strategy for high-throughput evaluation of potential critical quality attributes of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. MAbs 2022, 14 (1), 2133674 10.1080/19420862.2022.2133674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollastrini J.; Dillon T. M.; Bondarenko P.; Chou R. Y. Field flow fractionation for assessing neonatal Fc receptor and Fcgamma receptor binding to monoclonal antibodies in solution. Anal. Biochem. 2011, 414 (1), 88–98. 10.1016/j.ab.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondarenko P. V.; Nichols A. C.; Xiao G.; Shi R. L.; Chan P. K.; Dillon T. M.; Garces F.; Semin D. J.; Ricci M. S. Identification of critical chemical modifications and paratope mapping by size exclusion chromatography of stressed antibody-target complexes. MAbs 2021, 13 (1), 1887629 10.1080/19420862.2021.1887629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodall D. W.; Thomson C. A.; Dillon T. M.; McAuley A.; Green L. B.; Foltz I. N.; Bondarenko P. V. Native SEC and Reversed-Phase LC-MS Reveal Impact of Fab Glycosylation of Anti-SARS-COV-2 Antibodies on Binding to the Receptor Binding Domain. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95 (42), 15477–15485. 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c05554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y.; Xing T.; Wang S.; Li N. Versatile, Sensitive, and Robust Native LC-MS Platform for Intact Mass Analysis of Protein Drugs. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2020, 31 (10), 2171–2179. 10.1021/jasms.0c00277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y.; Xing T.; Liu A. P.; Zhang Z.; Wang S.; Li N. Post-Column Denaturation-Assisted Native Size-Exclusion Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry for Rapid and In-Depth Characterization of High Molecular Weight Variants in Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibodies. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 32 (12), 2885–2894. 10.1021/jasms.1c00289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Coillie J.; Schulz M. A.; Bentlage A. E. H.; de Haan N.; Ye Z.; Geerdes D. M.; van Esch W. J. E.; Hafkenscheid L.; Miller R. L.; Narimatsu Y.; et al. Role of N-Glycosylation in FcgammaRIIIa interaction with IgG. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 987151 10.3389/fimmu.2022.987151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. M.; Ashkenazi A. Fcgamma receptors enable anticancer action of proapoptotic and immune-modulatory antibodies. J. Exp Med. 2013, 210 (9), 1647–1651. 10.1084/jem.20131625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn F.; Ravetch J. V. Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol 2008, 8 (1), 34–47. 10.1038/nri2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn F.; Gordan S.; Lux A. FcgammaR dependent mechanisms of cytotoxic, agonistic, and neutralizing antibody activities. Trends Immunol 2015, 36 (6), 325–336. 10.1016/j.it.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Boesen C. C.; Radaev S.; Brooks A. G.; Fridman W. H.; Sautes-Fridman C.; Sun P. D. Crystal structure of the extracellular domain of a human Fc gamma RIII. Immunity 2000, 13 (3), 387–395. 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondermann P.; Huber R.; Oosthuizen V.; Jacob U. The 3.2-A crystal structure of the human IgG1 Fc fragment-Fc gammaRIII complex. Nature 2000, 406 (6793), 267–273. 10.1038/35018508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barb A. W.; Prestegard J. H. NMR analysis demonstrates immunoglobulin G N-glycans are accessible and dynamic. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7 (3), 147–153. 10.1038/nchembio.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; From NLM Medline.

- Shields R. L.; Lai J.; Keck R.; O’Connell L. Y.; Hong K.; Meng Y. G.; Weikert S. H.; Presta L. G. Lack of fucose on human IgG1 N-linked oligosaccharide improves binding to human Fcgamma RIII and antibody-dependent cellular toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277 (30), 26733–26740. 10.1074/jbc.M202069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junttila T. T.; Parsons K.; Olsson C.; Lu Y.; Xin Y.; Theriault J.; Crocker L.; Pabonan O.; Baginski T.; Meng G.; et al. Superior in vivo efficacy of afucosylated trastuzumab in the treatment of HER2-amplified breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010, 70 (11), 4481–4489. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa R.; Natsume A.; Uehara A.; Wakitani M.; Iida S.; Uchida K.; Satoh M.; Shitara K. IgG subclass-independent improvement of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity by fucose removal from Asn297-linked oligosaccharides. J. Immunol Methods 2005, 306 (1–2), 151–160. 10.1016/j.jim.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez L. M.; Penny D. M.; Bjorkman P. J. Stoichiometry of the interaction between the major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor and its Fc ligand. Biochemistry 1999, 38 (29), 9471–9476. 10.1021/bi9907330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higel F.; Seidl A.; Sorgel F.; Friess W. N-glycosylation heterogeneity and the influence on structure, function and pharmacokinetics of monoclonal antibodies and Fc fusion proteins. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 2016, 100, 94–100. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold J. N.; Wormald M. R.; Sim R. B.; Rudd P. M.; Dwek R. A. The impact of glycosylation on the biological function and structure of human immunoglobulins. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 25, 21–50. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; From NLM Medline.

- Subedi G. P.; Barb A. W. The immunoglobulin G1 N-glycan composition affects binding to each low affinity Fc gamma receptor. MAbs 2016, 8 (8), 1512–1524. 10.1080/19420862.2016.1218586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gstöttner C.; Lippold S.; Hook M.; Yang F.; Haberger M.; Wuhrer M.; Falck D.; Schlothauer T.; Domínguez-Vega E. Benchmarking glycoform-resolved affinity separation - mass spectrometry assays for studying FcgammaRIIIa binding. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1347871 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1347871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenzer A.; Kruse L.; Jooß K.; Neusüß C. Capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry for protein analyses under native conditions: Current progress and perspectives. Proteomics 2023, 24 (3–4), e2300135 10.1002/pmic.202300135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You J.; Zhang J.; Wang J.; Jin M. Cysteine-Based Coupling: Challenges and Solutions. Bioconjug Chem. 2021, 32 (8), 1525–1534. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.1c00213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.