Abstract

Background

Emergency contraception can prevent pregnancy when taken after unprotected intercourse. Obtaining emergency contraception within the recommended time frame is difficult for many women. Advance provision could circumvent some obstacles to timely use.

Objectives

To summarize randomized controlled trials evaluating advance provision of emergency contraception to explore effects on pregnancy rates, sexually transmitted infections, and sexual and contraceptive behaviors.

Search methods

In November 2009, we searched CENTRAL, EMBASE, POPLINE, MEDLINE via PubMed, and a specialized emergency contraception article database. We also searched reference lists and contacted experts to identify additional published or unpublished trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials comparing advance provision and standard access (i.e., counseling which may or may not have included information about emergency contraception, or provision of emergency contraception on request at a clinic or pharmacy).

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently abstracted data and assessed study quality. We entered and analyzed data using RevMan 5.0.23.

Main results

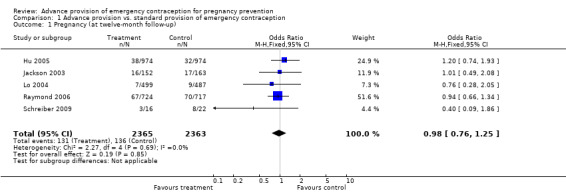

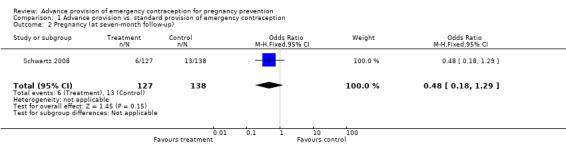

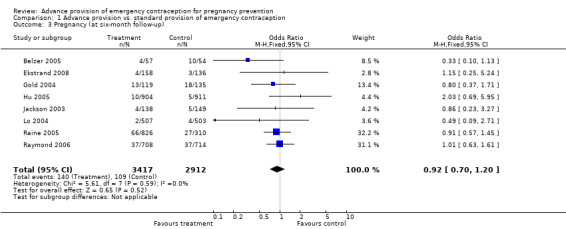

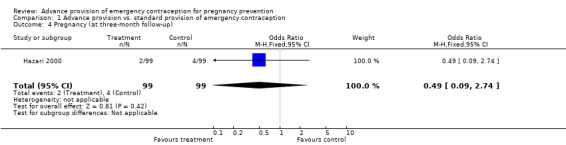

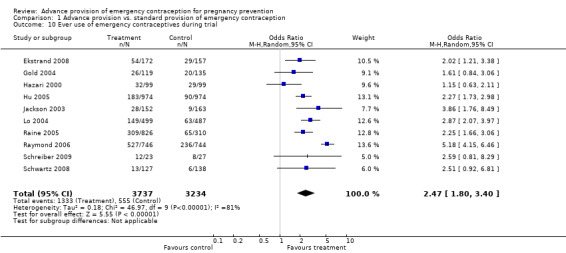

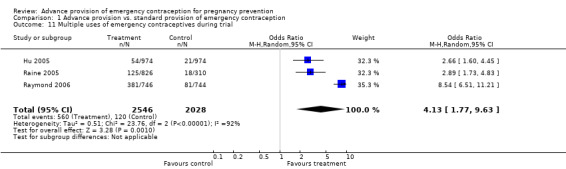

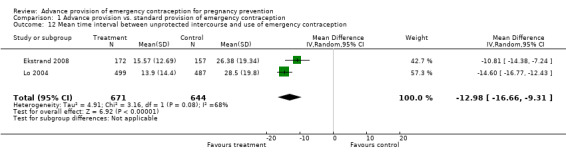

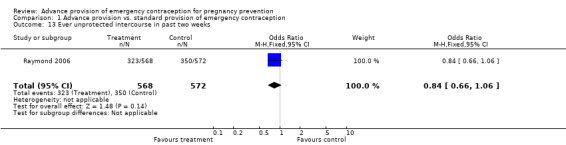

Eleven randomized controlled trials met our criteria for inclusion, representing 7695 patients in the United States, China, India and Sweden. Advance provision did not decrease pregnancy rates (odds ratio (OR) 0.98, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.76 to 1.25 in studies for which we included twelve‐month follow‐up data; OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.18 to 1.29 in a study with seven‐month follow‐up data; OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.20 in studies for which we included six‐month follow‐up data; OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.09 to 2.74 in a study with three‐month follow‐up data), despite reported increased use (single use: OR 2.47, 95% CI 1.80 to 3.40; multiple use: OR 4.13, 95% CI 1.77 to 9.63) and faster use (weighted mean difference (WMD) ‐12.98 hours, 95% CI ‐16.66 to ‐9.31 hours). Advance provision did not lead to increased rates of sexually transmitted infections (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.37), increased frequency of unprotected intercourse, or changes in contraceptive methods. Women who received emergency contraception in advance were equally likely to use condoms as other women.

Authors' conclusions

Advance provision of emergency contraception did not reduce pregnancy rates when compared to conventional provision. Results from primary analyses suggest that advance provision does not negatively impact sexual and reproductive health behaviors and outcomes. Women should have easy access to emergency contraception, because it can decrease the chance of pregnancy. However, the interventions tested thus far have not reduced overall pregnancy rates in the populations studied.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Pregnancy Rate; Contraception, Postcoital; Contraception, Postcoital/methods; Contraception, Postcoital/statistics & numerical data; Contraceptives, Postcoital; Contraceptives, Postcoital/administration & dosage; Contraceptives, Postcoital/supply & distribution; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Sexually Transmitted Diseases; Sexually Transmitted Diseases/epidemiology

Plain language summary

Easier access to emergency contraception to help women prevent unwanted pregnancy

Emergency contraceptive pills can prevent unwanted pregnancy if taken soon after unprotected sex. Getting a prescription for emergency contraception can be difficult and time‐consuming. Giving emergency contraception to women in advance could ensure that women have it on hand in case they need it. We searched for studies comparing women who got emergency contraception in advance to women who got it in standard ways. We examined whether these groups had different rates of pregnancy or sexually transmitted infections. We also studied how often and how quickly both groups used emergency contraception. Finally, we looked at whether advance provision of emergency contraception changed sexual behavior. Studies showed that the chance of pregnancy was similar regardless of whether or not women have emergency contraception on hand before unprotected sex. Women who had emergency contraception in advance were more likely to report use of the medication, and to use it sooner after sex. Having emergency contraception on hand did not change use of other kinds of contraception or change sexual behavior.

Background

Emergency contraception can prevent pregnancy when taken within 120 hours of unprotected intercourse. Several types of emergency contraception regimens exist, including an estrogen‐progestin combination (sometimes called "combined regimen" or "Yuzpe regimen"), levonorgestrel alone, and mifepristone. An alternate method of emergency contraception is post‐coital insertion of a copper‐bearing intrauterine device (IUD), but this review does not cover IUDs as emergency contraceptives.

Effectiveness and side effects vary by regimen (Cheng 2008). A meta‐analysis of eight studies suggested that combined regimens reduce the risk of pregnancy by about 74% when taken within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse (Trussell 1999). A more recent analysis using potentially improved methodology suggested lower effectiveness rates, with the two largest studies showing rates of 47% and 53% (Trussell 2003). Levonorgestrel regimens are more effective than combined regimens (with estimates ranging from 59‐94%), with less nausea and vomiting (Task Force 1998; Trussell 2006a).

Several barriers discourage widespread and timely use of emergency contraception, including limited knowledge among women and a lack of routine counseling by providers and/or willingness to prescribe the medication. In some countries, emergency contraception is available only after obtaining a prescription, which can be difficult and time‐consuming, particularly on holidays or weekends when most clinics and physicians' offices are closed. Moreover, some women find it difficult or embarrassing to request emergency contraception from their physician, and others may not have a primary health care provider. Emergency contraception should be taken as soon as possible, and most guidelines suggest taking the medication within 72 or 120 hours of unprotected intercourse. Even under ideal circumstances, obtaining a prescription within 72 hours can be difficult (Trussell 2000); to date, no studies have investigated barriers to accessing a prescription within the 120 hour time limit. Some countries sell emergency contraception over‐the‐counter without a prescription, and others allow women to obtain emergency contraception directly from a pharmacist without a doctor's prescription under collaborative practice agreements with physicians or state approved protocols.

Providing emergency contraception before it is needed in case unprotected intercourse occurs gives women rapid access to the medication. This strategy was first evaluated in a 1998 study (Glasier 1998) and has received increased attention since that time. However, some worry that having emergency contraception on hand may encourage repeat or incorrect use, increase risky sexual behavior, or discourage use of ongoing or more reliable methods of contraception (particularly barrier methods), thereby increasing the risk of pregnancy or sexually transmitted infections (Gold 1997; Golden 2001; Sherman 2001).

Objectives

To summarize randomized controlled trials evaluating advance provision of emergency contraceptive pills.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

This review included all randomized controlled trials in English that evaluated advance provision of emergency contraception. We excluded studies that failed to clearly report the proportion of women in each treatment arm who became pregnant (as determined by self‐report and/or medical testing) during follow‐up, and for which we were unable to obtain clear data by asking authors directly.

Types of participants

Women of reproductive age.

Types of interventions

Any emergency contraceptive regimen (combined, levonorgestrel, or mifepristone) provided in advance of need compared to a control group, defined as any of the following: counseling which may or may not include a discussion of emergency contraception, or provision of emergency contraception on request at a clinic or pharmacy.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcome measures were pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection rates. Secondary outcomes were frequency of emergency contraception use, unprotected intercourse, use of more effective methods of contraception, condom use, delay in taking emergency contraception after unprotected intercourse, and knowledge about emergency contraception.

Search methods for identification of studies

See Helmerhorst 2001 for methods used in reviews of the Fertility Regulation Group.

During August 2006, we identified relevant trials from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) on the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, POPLINE, MEDLINE via PubMed, and the website of the International Consortium for Emergency Contraception (www.cecinfo.org/database/who/index.php). Where possible, searches were restricted to human studies only. We restricted our search to English (Moher 2000; Juni 2002). We updated our literature search in November 2009.

We used the following strategy to search CENTRAL: ((postcoital or emergency) and contracept* and (advance* or self administr*))

We used the following strategy to search EMBASE: ((('emergency'/exp OR 'emergency') OR ('emergency'/exp OR 'emergency')) OR postcoit*) AND (contracept*) AND (advance AND provision OR advanced AND provision) AND [english]/lim AND [humans]/lim We used the following strategy to search POPLINE: (emergency contraception/contraceptive agents, postcoital/fertility control, postcoital) & (advance provision/advanced provision/self administration)

We used the following strategy to search MEDLINE via PubMed: (emergency contracepti* OR contraception, postcoital OR contraceptives, postcoital) AND (advance OR advanced OR self administ* OR home)

We used the following strategy to search the database of scientific articles on the website of the International Consortium for Emergency Contraception (ICEC) (http://www.cecinfo.org/database/who/index.php): "advance" or "advanced"

We also searched reference lists of included studies for information about additional trials and contacted experts in the field for information on additional published or unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

All studies that met our inclusion criteria were independently evaluated by two reviewers. We assessed the methodological quality of each study using the guidelines described in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook (Alderson 2004). We designed a data abstraction form, and the two reviewers abstracted the data separately. Discrepancies about the inclusion of studies or about abstracted data were resolved by discussion. When necessary, we contacted researchers to obtain additional information about study methods or outcome measures. We entered and analyzed the data using Review Manager 5.

We calculated odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals for dichotomous variables and weighted mean averages (WMA) for continuous variables for which means and standard deviations were reported. We tested the outcome data for heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, and in cases where I2 exceeded 50%, we employed a DerSimonian and Laird random‐effects model to provide a more conservative estimate of significance (DerSimonian 1986; Higgins 2003). Finally, we conducted sensitivity analyses based on rates of loss to follow‐up (Schulz 2006), in which studies that had rates of loss to follow‐up over 20% were excluded.

One study (Belzer 2005) collected 12‐month follow‐up information, but due to the presentation of results, we were only able to include 6‐month follow‐up information. In cases where data were available, we calculated statistics using an intent‐to‐treat analysis if the author failed to do so (Belzer 2005, see also Trussell 2006b).

To explore whether intervention effect waned over time, we contacted authors of studies with 12 months of follow‐up to obtain pregnancy outcomes at six months, and pooled these outcomes with studies which had a total follow‐up time of six months. Six‐month pregnancy outcomes for Schreiber 2009 were not available. To explore whether pregnancy outcomes differed according to type of regimen, we performed subgroup analyses of studies using levonorgestrel, Yuzpe regimen, levonorgestrel or Yuzpe, and mifepristone.

Results

Description of studies

Eleven randomized controlled trials (Hazari 2000; Jackson 2003; Gold 2004; Lo 2004; Belzer 2005; Hu 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Ekstrand 2008; Schwartz 2008; Schreiber 2009) met our inclusion criteria. The total number of randomized participants was 7695, with sample sizes ranging from 50 to 2000. Raine 2005 enrolled 2117 total participants, but this review used only two treatment groups of that study. Seven studies were conducted in the United States (Jackson 2003; Gold 2004; Belzer 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Schwartz 2008; Schreiber 2009), with five in California and the rest in Nevada, North Carolina, or Pennsylvania. One study was conducted in Hong Kong (Lo 2004) and one in mainland China (Hu 2005). One study was conducted in India (Hazari 2000) and one was conducted in Sweden (Ekstrand 2008). Six studies (Gold 2004; Belzer 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Ekstrand 2008; Schreiber 2009) focused specifically on younger populations, and two of those (Belzer 2005; Schreiber 2009) focused on adolescent mothers. Two studies primarily enrolled post‐partum women (Jackson 2003; Hu 2005). Three studies recruited women from family planning clinics (Lo 2004; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006), two recruited from other clinics (Ekstrand 2008; Schwartz 2008), four recruited from hospitals (Jackson 2003; Gold 2004; Hu 2005; Schreiber 2009), and one recruited adolescent mothers receiving case management services (Belzer 2005). The recruitment site was unclear in one study (Hazari 2000).

Exclusion criteria for baseline contraceptive use varied greatly between the studies. The most restrictive criteria excluded women using or planning to use any hormonal method or an IUD (Lo 2004; Hu 2005). Raymond 2006 excluded women for using some hormonal methods or sterilization, and Raine 2005 excluded women for using some hormonal methods. Schwartz 2008 excluded IUD users, women who had tubal sterilization or had partners who had undergone a vasectomy, lesbians, and women who had a hysterectomy. Gold 2004 excluded women using long acting contraceptive methods (IUD, implants and injectables), and Belzer 2005 excluded only IUD and implant users. Jackson 2003 excluded women who were sterilized or had a sterilized partner. Three studies had minimal exclusion criteria: Hazari 2000 excluded only women who were determined at baseline to be pregnant, Schreiber 2009 excluded women who desired a pregnancy in the next year, and Ekstrand 2008 did not specify exclusion criteria based on contraceptive use. Although several studies included post‐partum women, only one study specified excluding women who were currently breastfeeding (Raymond 2006).

Control groups also differed considerably. Three studies did not necessarily provide any information about emergency contraception to the control group (Jackson 2003; Schwartz 2008; Schreiber 2009) Two studies (Belzer 2005; Hu 2005) specifically provided information about emergency contraception to the control group, but did not facilitate access to the medication in any other way. Control participants in six studies (Hazari 2000; Gold 2004; Lo 2004; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Schreiber 2009) were able to obtain emergency contraception on request at the clinic, although not necessarily through study staff. One study provided the control group with a dose of emergency contraception (Ekstrand 2008). Two studies reported providing all participants with condoms (Hazari 2000; Hu 2005), while Ekstrand 2008 provided condoms only to the intervention group.

The number of courses of emergency contraception provided in advance ranged from one to three. Seven studies provided only one course of emergency contraception in advance (Hazari 2000; Jackson 2003; Gold 2004; Belzer 2005; Ekstrand 2008; Schwartz 2008; Schreiber 2009). Gold 2004 offered two additional courses on request at the study office, Belzer 2005 and Schreiber 2009 offered replacement packs through the study, and Jackson 2003 provided instructions on obtaining additional emergency contraceptive pills (but did not specify if that was through the study office or by prescription). One study (Raymond 2006) provided two courses in advance and made particular effort to ensure that all women in the advance provision group had two courses available at all times. Finally, three studies provided three courses of emergency contraception in advance (Lo 2004; Hu 2005; Raine 2005), and one (Lo 2004) specifically noted that women using all three packs were instructed to return for contraceptive counseling and, if appropriate, given three additional packets.

Most trials administered levonorgestrel pills. Seven studies used the same formulation of pills (two tablets of 0.75 mg levonorgestrel) (Lo 2004; Belzer 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Ekstrand 2008; Schwartz 2008; Schreiber 2009). In addition, Gold 2004 replaced a Yuzpe regimen (200 µg ethinyl estradiol and 2 mg norgestrel) with levonorgestrel when it became the standard of care mid‐way through their study. Two earlier studies used a combined regimen (Hazari 2000; Jackson 2003), and one study based in China provided 10 mg mifepristone (Hu 2005).

Follow‐up ranged from three to 12 months. Six studies aimed to follow all participants for one year (Jackson 2003; Lo 2004; Belzer 2005; Hu 2005; Raymond 2006; Schreiber 2009). However, we report only on six‐month follow‐up data for most outcomes (except pregnancy) in Jackson 2003 and all outcomes in Belzer 2005, since these studies provided six‐month data and six‐ to 12‐month data, but not cumulative 12‐month data. Three studies followed all participants for six months (Gold 2004; Raine 2005; Ekstrand 2008), one study followed participants for seven months (Schwartz 2008) and one study followed participants for three months (Hazari 2000).

All studies attempted to measure pregnancy, whereas only four studies measured sexually transmitted infections (Gold 2004; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006;Ekstrand 2008). Seven studies solely relied on self‐reported pregnancy data (Jackson 2003; Gold 2004; Belzer 2005; Hu 2005; Ekstrand 2008; Schwartz 2008; Schreiber 2009), whereas four studies used more objective pregnancy detection methods, comprised of some combination of self‐report, testing at follow‐up, or medical chart review (Hazari 2000; Lo 2004; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006). Among the studies which measured sexually transmitted infections, two used self‐reported data (Gold 2004; Ekstrand 2008) and two used combinations of more objective methods including testing at follow‐up and medical chart review (Raine 2005; Raymond 2006).

Risk of bias in included studies

Eight studies used computer‐generated randomization sequences (Hazari 2000; Lo 2004; Belzer 2005; Hu 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Schwartz 2008; Schreiber 2009). One study randomized in blocks of four using a table of random digits (Ekstrand 2008). One study had participants select a colored condom from a covered bucket to determine allocation (Gold 2004), and another used cluster randomization by date of discharge in order to avoid accidental crossover (Jackson 2003).

Seven studies had adequate allocation concealment methods. Four used either sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes or identical treatment boxes (Lo 2004; Hu 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006) while three (Gold 2004; Hazari 2000; Schwartz 2008) used schemes undecipherable to clinic staff. Three studies had unclear allocation concealment (Belzer 2005; Ekstrand 2008; Schreiber 2009). One study had inadequate concealment methods that allowed for assignment prediction (Jackson 2003).

Three studies (Hu 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006) provided sample size calculations based on detecting a decrease in pregnancy rates. However, Hu 2005 was underpowered due to unexpectedly low pregnancy rates in their study population. The other eight studies primarily investigated behavior change and were not powered to measure pregnancy. Of these, four (Jackson 2003; Gold 2004; Lo 2004; Ekstrand 2008; Schwartz 2008) calculated sample sizes in accordance with anticipated differences in emergency contraceptive use or timing of use between groups, two (Hazari 2000; Belzer 2005) did not provide sample‐size calculations, and one feasibility trial used a sample size of convenience (Schreiber 2009).

Five studies had loss to follow‐up under 20% (Hazari 2000; Lo 2004; Hu 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006). Six studies had larger losses (Jackson 2003; Gold 2004; Belzer 2005; Ekstrand 2008; Schwartz 2008; Schreiber 2009), ranging up to 41% of participants lost to follow‐up (Schwartz 2008). In addition, Gold 2004 showed differential loss to follow‐up.

Effects of interventions

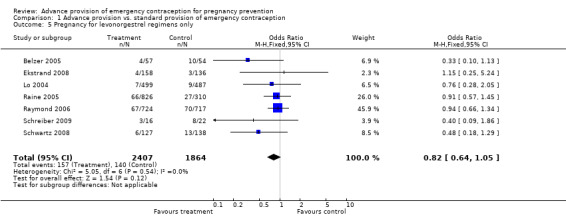

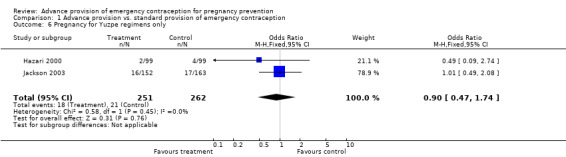

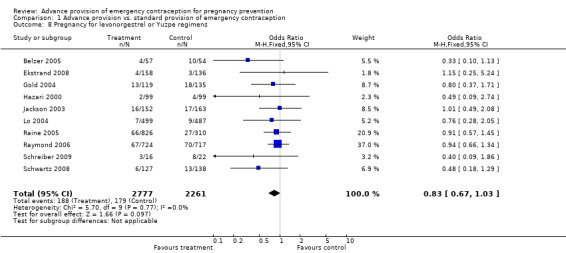

None of the studies found significant differences in pregnancy rates (Hazari 2000; Jackson 2003; Gold 2004; Lo 2004; Belzer 2005; Hu 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Ekstrand 2008; Schwartz 2008; Schreiber 2009), including the two studies that were adequately powered to detect a difference (Raine 2005; Raymond 2006). Furthermore, results from the pooled analyses showed no significant difference in pregnancy rates between advance provision and control groups. The combined OR for pregnancy comparing women receiving emergency contraception in advance to women in the control group was 0.98 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.25) in studies with 12‐month follow‐up, 0.48 (95% CI 0.18 to 1.29) in a study with seven‐month follow‐up information, 0.92 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.20) in studies for which we included six‐month follow‐up information, and 0.49 (95% CI: 0.09 to 2.74) for one study with three‐month follow‐up data. Restricting this comparison in a sensitivity analysis to include only studies with a loss to follow‐up rate under 20% did not substantially change the results (twelve‐month follow‐up: OR 1.0; 95% CI 0.76 to 1.31; six‐month follow‐up: OR 1.00; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.37; three‐month follow‐up: OR 0.49; 95% CI 0.09 to 2.74). None of the analyses pooled by regimen type demonstrated a reduction in pregnancy rates (levonorgestrel only: OR 0.82, 95% CI: 0.64 to 1.05; Yuzpe only: OR 0.90, 95% CI: 0.47 to 1.74; levonorgestrel or Yuzpe: OR 0.83, 95% CI: 0.67 to 1.03; and mifepristone: OR 1.20, 95% CI: 0.74 to 1.93).

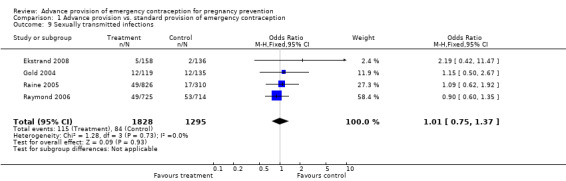

None of the four studies that measured sexually transmitted infection rates found significant differences between groups (Gold 2004; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Ekstrand 2008). The combined OR for sexually transmitted infections was 1.01 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.37). Restricting this analysis to only studies with a loss to follow‐up rate under 20% did not substantially change the results (OR 0.96; 95% CI 0.69 to 1.33).

Reported emergency contraceptive use was significantly higher in the advance provision group in six studies (Jackson 2003; Lo 2004; Hu 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Ekstrand 2008), and in four studies (Hazari 2000;Gold 2004; Schwartz 2008; Schreiber 2009), emergency contraceptive use was higher but the difference did not reach statistical significance. Belzer 2005 reported emergency contraceptive use only for a subgroup of participants and we did not include those results in this analysis. The combined OR for emergency contraception use for all studies was 2.47 (95% CI 1.80 to 3.40). The sensitivity analysis including only studies with a loss to follow‐up rate under 20% yielded similar results (OR 2.55; 95% CI 1.64 to 3.97). A secondary analysis which used predictive modeling to estimate the baseline risk of pregnancy suggested that women at low baseline risk of pregnancy may have been more likely to use EC repeatedly than high risk women (Baecher 2009). Three studies (Hu 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006) also showed that women in the advance provision group were significantly more likely to use emergency contraception two or more times (OR: 4.13; 95% CI 1.77 to 9.63); no sensitivity analysis was conducted for this outcome since all studies in the original analysis had loss to follow‐up under 20%.

The percentage of women who did not use emergency contraception after unprotected intercourse ranged widely and was reported in different ways. Four studies (Jackson 2003; Lo 2004; Hu 2005; Raymond 2006) reported non‐use of emergency contraception among women who became pregnant. Three studies reported non‐use among women who had unprotected intercourse (Gold 2004; Raine 2005; Ekstrand 2008). In all studies reporting on non‐use, non‐use was lower among participants in the advance provision group compared to controls. Belzer 2005 reported use of emergency contraception among a subgroup of participants (data not reported).

Hu 2005 reported non‐use of emergency contraception among women who became pregnant during one year of follow‐up (n=70); 79% in the advance provision group and 100% in the control group did not use emergency contraception during the cycle in which they conceived. Among women who became pregnant in Jackson 2003 (n=27), 64% in the advance provision group and 100% in the control group did not use emergency contraception. Among women who became pregnant in Lo 2004 (n=16), 71% in the advance provision group and 100% in the control group did not report using emergency contraception during the cycle in which the pregnancy occurred. Raymond 2006 reported that for the 148 menstrual cycles in which women experienced pregnancy, 77% of women in the advance provision group and 97% of women in the control group did not use emergency contraception during those cycles.

Gold 2004 reported that at six‐month follow‐up, 26% of participants in both arms had unprotected intercourse in the past month, but 92% of women in the advance provision group and 94% in the control group did not report use of emergency contraception. In Raine 2005, among women who reported ever having unprotected sex, 6% of women in the advance provision group and 49% of women in the control group did not report using emergency contraception during the study period. Ekstrand 2008 reported that half of adolescent girls reporting unprotected intercourse during the previous six months used ECP afterwards, with significantly more in intervention group using emergency contraceptive pills (58%) than in the control group (37%) (p=0.02).

In addition, emergency contraception was sometimes used incorrectly. Lo 2004 reported that although all participants took the first dose within 72 hours of intercourse, 17% of women in the advance provision group took the second dose of levonorgestrel incorrectly. No women in the control group reported taking the second dose incorrectly. Jackson 2003 reported incorrect use only among women who became pregnant and who reported using emergency contraception in the cycle in which they conceived (n=4). Two of these four women used emergency contraception incorrectly. Hu 2005 reported that all women in the advance provision group took emergency contraception within the recommended 120 hours, but did not report on correct use by control participants. Eight studies (Hazari 2000; Gold 2004; Belzer 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Ekstrand 2008; Schwartz 2008; Schreiber 2009) did not report on incorrect use.

Five studies collected information on reported time intervals between unprotected intercourse and use of emergency contraception. In general, this interval was shorter for women receiving emergency contraception in advance. Two studies provided mean time and standard deviation (Lo 2004; Ekstrand 2008). Women with advance provision took emergency contraception a mean of 12.98 hours earlier than women with standard provision (WMD ‐13.98, 95% CI ‐16.66 to ‐9.31 hours). Two other studies reached similar conclusions, the first with a comparison of median times of 11.4 hours for advance provision vs. 21.8 hrs for control (p=0.005) (Gold 2004), the second with imputed median midpoints of 12 hours for advance provision vs. 36 hours for control (p<0.010) (Raymond 2006). Raine 2005 also found a shorter delay for the advance provision group (p=0.008). One study suggested no difference in timing (eight hours for both groups), but this study was conducted in China, where levonorgestrel was available over‐the‐counter at the time of the study (Hu 2005). A small number of women (n=2) in this study did report purchasing levonorgestrel over the counter.

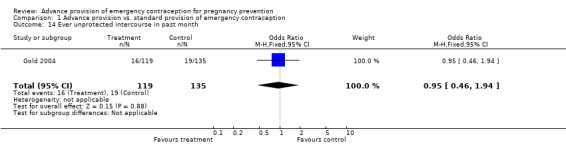

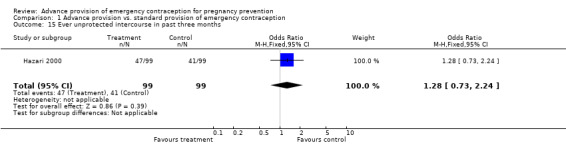

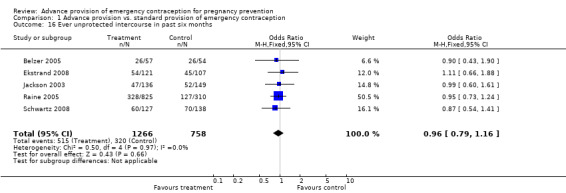

Eight studies compared the reported frequency of unprotected intercourse using different time frames (Hazari 2000; Jackson 2003; Gold 2004; Belzer 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Ekstrand 2008; Schwartz 2008). None showed any difference between comparison groups (unprotected intercourse in past two weeks: OR 0.84 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.06); unprotected intercourse in past month: OR 0.95 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.94); unprotected intercourse in past three months: OR 1.28 (95% CI: 0.73 to 2.24); unprotected intercourse in past six months: OR 0.96 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.16)).

Six studies examined change in contraceptive use using a variety of measurements (Jackson 2003; Belzer 2005; Hu 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Ekstrand 2008). Belzer 2005 described this information only for a subgroup (data not reported). Jackson 2003 found no differences between treatment arms in consistency of contraceptive use or type of method use during six months of follow‐up, and among women who only used condoms, there was no decrease in condom use among the group with advance provision of emergency contraception. Similarly, Hu 2005, Raine 2005 and Ekstrand 2008 reported no differences between treatment arms in patterns of contraceptive use or method change. Finally, Raymond 2006 reported that use of contraception (other than emergency contraception) as reported at follow‐up did not differ significantly by group. In this study, the proportion of sexually active women who did not use any form of contraception decreased slightly in both groups during follow‐up. Secondary analyses of this study suggested that advance provision may have caused an increase in unprotected or underprotected sex (Raymond 2008), and that advance provision may have caused women to substitute EC for other methods (Weaver 2009), but these findings should be considered hypothesis‐generating and do not influence our overall conclusions.

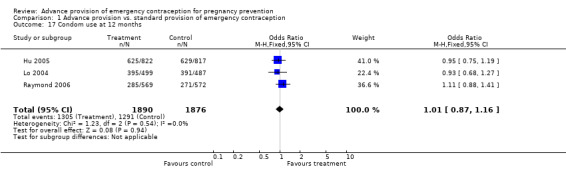

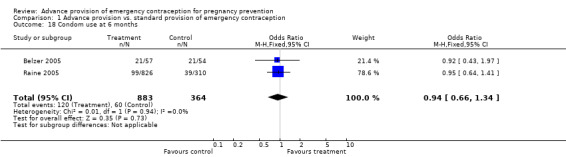

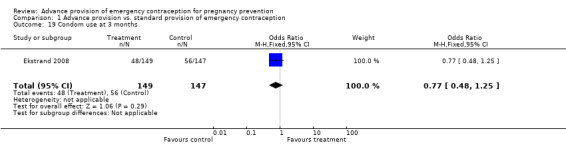

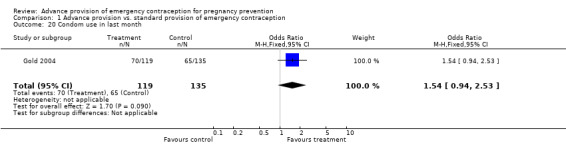

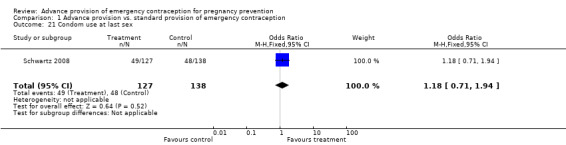

Eight studies looked at condom use; none found significant differences between groups (Lo 2004; Belzer 2005; Hu 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Gold 2004; Ekstrand 2008; Schwartz 2008). The OR for condom use at 12 months was 1.01 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.16); at six months: OR 0.94 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.34), at three months: OR 0.77 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.25), in last month: OR 1.54 (95% CI 0.94 to 2.53), and at last sex: OR 1.18 (95% CI 0.71 to 1.94).

None of the studies reported adverse events (Hazari 2000; Jackson 2003; Gold 2004; Lo 2004; Belzer 2005; Hu 2005; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Ekstrand 2008; Schwartz 2008; Schreiber 2009).

Discussion

Advance provision of emergency contraception did not reduce unplanned pregnancies when compared to standard access. None of the adequately powered trials found a decrease in pregnancy rates with advance provision of emergency contraception (Raine 2005; Raymond 2006). Pooled estimates also showed no difference in pregnancy rates, indicating that based on available data, advance provision of emergency contraception does not lead to reduced rates of unintended pregnancy. Analyses by length of follow‐up and by type of regimen did not change results.

This conclusion conflicts with earlier optimistic projections of the potential public health impact of improved access (Trussell 1992). Emergency contraception is more effective than placebo in preventing unwanted pregnancy (Raymond 2004), and advance provision increases use and shortens time between unprotected intercourse and emergency contraceptive use. Since evidence now supports ia single dose of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, and several countries now market levonorgestrel emergency contraception in a single dose, incorrect use will likely be less of a problem in the future (Arowojolu 2002; von Hertzen 2002). Nevertheless, women may not perceive themselves to be at risk of pregnancy and may fail to use the method after unprotected sex has occurred, despite ready availability. Research suggests that unperceived pregnancy risk, concerns about side effects, and inconvenience are some of the reasons why women may not use emergency contraception when needed (Sorensen 2000; Moreau 2005; Rocca 2007; Goulard 2006). A secondary analysis of data from Raymond 2006 suggested that women at the lowest baseline risk of pregnancy may have been more likely to use EC repeatedly than high risk women, which may help to explain why no effect on pregnancy was found (Baecher 2009).

As with other contraceptive methods, the disparity between theoretical and actual effectiveness can be large (Steiner 1996). More precise estimates of efficacy may help to shed light on advance provision's lack of impact on unintended pregnancy. These trials share a common weakness. Reported information on use of emergency contraception, frequency of unprotected intercourse, and changes in contraceptive patterns was of unknown validity. Since these self reports lacked objective verification, this information should be viewed with caution (Stuart 2009). Objective evidence indicates that self reports on use of contraceptives (Lawson 1998; Macaluso 2003; Walsh 2003; Galvao 2005) and other medications (Landry 2006) are inaccurate, and that self‐report of unprotected intercourse is inferior to other ascertainment methods (Rogers 2005). Some degree of underreporting of pregnancies may have occurred in both the advance provision and control groups in these trials, particularly those trials using only self‐reported data. Induced abortions are routinely underreported (Fu 1998). However, results from the trials relying on pregnancy testing were consistent with results from the trials using self‐reports of pregnancy.

Advance provision of emergency contraception consistently increased its reported use and usually shortened the reported interval between unprotected intercourse and drug administration. However, changes in these measures did not correlate with changes in pregnancy rates.

The quality of these randomized controlled trials varied widely. While many had good methods of randomization and allocation concealment, follow‐up rates differed greatly. One trial planned not to follow most participants after randomization (Walsh 2006), so we excluded it. In the view of Sackett and others, when losses exceed 20% of participants randomized, the credibility of a trial is suspect (Schulz 2006). Trials with high losses to follow‐up resemble cohort studies in their potential for bias. For the sake of completeness, we included trials with poor follow‐up and performed a sensitivity analysis with and without these reports; the results were similar.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Providing women with emergency contraception in advance of need does not reduce unintended pregnancy on a population level. Advance provision did not have any harmful effects in primary analyses: it did not increase rates of sexually transmitted infections, decrease condom use, encourage adoption of less reliable contraceptive methods, or otherwise negatively impact sexual and reproductive behavior. While derivative studies suggested theoretical concerns regarding increases in unprotected or underprotected sex, or potential substitution of EC for more effective methods, these findings should be considered tentative. Advance provision did increase use of emergency contraception and decrease the length of time between unprotected intercourse and use of emergency contraception. Conclusions about population level effects should not impede efforts to ensure all women have access to emergency contraception when they need it. Women should be given information about and easy access to emergency contraception because individual women can decrease their chances of pregnancy by using the method. However, current data on advance provision of emergency contraception indicate that tested interventions will not reduce overall unintended pregnancy rates.

Implications for research.

Future research should address the behavioral issues surrounding the failure to use emergency contraception when needed, even when it is readily available.

Feedback

No cost‐effective public health strategy, 28 May 2013

Summary

I have a slight concern about one of the sentences in the final paragraph of the "Background" section of this review, which reads: "Economic modeling indicates that advance provision of emergency contraception is a cost‐effective public health strategy".

Look at the referenced paper, I don't think the situation is nearly as clear cut as this sentence suggests. The model appears to rely on the assumption that advanced supply reduces pregnancies, while the review itself finds no evidence for this assumption. The reference paper also includes the sentence "At the population level, advanced provision of ECPs has not been demonstrated to be cost effective."

I think the sentence as printed in the review doesn't reflect the uncertainty here, particularly since the review itself undermines the economic model on which the statement that EC is cost‐effective relies. I think that it would be more accurate to say that the cost‐effectiveness is uncertain.

Many thanks, Simon Howard

Reply

I agree with Simon Howard's critique. I think the confusion stems from the fact that the reference cited is a living document (http://ec.princeton.edu/questions/EC‐review.pdf) and thus the conclusions of the reference paper may have been modified over time. I would be happy to simply delete that sentence from our review.

Contributors

Comment by Dr. Simon Howard

Answer by Dr. Chelsea Polis and Prof David Grimes

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 July 2013 | Amended | Sentence deleted from Background section in response to feedback. Contact details updated. |

| 9 July 2013 | Feedback has been incorporated | See Feedback for details. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2005 Review first published: Issue 2, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 January 2010 | New search has been performed | Added information from 3 new included studies and noted new excluded studies. |

| 14 April 2009 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 14 January 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely grateful to the late Charlotte Ellertson, who conceived the idea for this review and provided generous encouragement and advice. We also thank Carol Manion for assistance with our search strategy, and Elizabeth Raymond and James Trussell for their helpful comments.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pregnancy (at twelve‐month follow‐up) | 5 | 4728 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.76, 1.25] |

| 2 Pregnancy (at seven‐month follow‐up) | 1 | 265 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.18, 1.29] |

| 3 Pregnancy (at six‐month follow‐up) | 8 | 6329 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.70, 1.20] |

| 4 Pregnancy (at three‐month follow‐up) | 1 | 198 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.09, 2.74] |

| 5 Pregnancy for levonorgestrel regimens only | 7 | 4271 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.64, 1.05] |

| 6 Pregnancy for Yuzpe regimens only | 2 | 513 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.47, 1.74] |

| 7 Pregnancy for mifepristone regimens only | 1 | 1948 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.74, 1.93] |

| 8 Pregnancy for levonorgestrel or Yuzpe regimens | 10 | 5038 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.67, 1.03] |

| 9 Sexually transmitted infections | 4 | 3123 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.75, 1.37] |

| 10 Ever use of emergency contraceptives during trial | 10 | 6971 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.47 [1.80, 3.40] |

| 11 Multiple uses of emergency contraceptives during trial | 3 | 4574 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 4.13 [1.77, 9.63] |

| 12 Mean time interval between unprotected intercourse and use of emergency contraception | 2 | 1315 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐12.98 [‐16.66, ‐9.31] |

| 13 Ever unprotected intercourse in past two weeks | 1 | 1140 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.66, 1.06] |

| 14 Ever unprotected intercourse in past month | 1 | 254 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.46, 1.94] |

| 15 Ever unprotected intercourse in past three months | 1 | 198 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.73, 2.24] |

| 16 Ever unprotected intercourse in past six months | 5 | 2024 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.79, 1.16] |

| 17 Condom use at 12 months | 3 | 3766 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.87, 1.16] |

| 18 Condom use at 6 months | 2 | 1247 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.66, 1.34] |

| 19 Condom use at 3 months | 1 | 296 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.48, 1.25] |

| 20 Condom use in last month | 1 | 254 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.54 [0.94, 2.53] |

| 21 Condom use at last sex | 1 | 265 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.71, 1.94] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 1 Pregnancy (at twelve‐month follow‐up).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 2 Pregnancy (at seven‐month follow‐up).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 3 Pregnancy (at six‐month follow‐up).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 4 Pregnancy (at three‐month follow‐up).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 5 Pregnancy for levonorgestrel regimens only.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 6 Pregnancy for Yuzpe regimens only.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 7 Pregnancy for mifepristone regimens only.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 8 Pregnancy for levonorgestrel or Yuzpe regimens.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 9 Sexually transmitted infections.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 10 Ever use of emergency contraceptives during trial.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 11 Multiple uses of emergency contraceptives during trial.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 12 Mean time interval between unprotected intercourse and use of emergency contraception.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 13 Ever unprotected intercourse in past two weeks.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 14 Ever unprotected intercourse in past month.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 15 Ever unprotected intercourse in past three months.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 16 Ever unprotected intercourse in past six months.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 17 Condom use at 12 months.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 18 Condom use at 6 months.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 19 Condom use at 3 months.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 20 Condom use in last month.

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance provision vs. standard provision of emergency contraception, Outcome 21 Condom use at last sex.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Belzer 2005.

| Methods | RCT. Computer generated randomization number table. Sealed envelopes (unclear whether opaque or sequentially numbered). 12 mo follow‐up, data reported in six mo intervals. We utilize only the six mo data. | |

| Participants | 160 adolescent mothers, 13‐20 yrs, mostly Hispanic, receiving case management services in a large metropolitan area. Excluded if attempting to get pregnant or using implant or an IUD. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group received 1 course levonorgestrel‐only regimen (two tabs 0.75 mg levonorgestrel), to be taken in two doses 12 h apart. Replacement pack provided if package used or lost. Control group received EC info only. | |

| Outcomes | Pregnancy rates, frequency of unprotected intercourse, condom use. | |

| Notes | Large loss to follow‐up (31% at six months). Original statistical analysis not intent‐to‐treat. All self‐reported data. No sample size calculation. Controls significantly more likely to report condom use and sexual activity at baseline; differences not controlled for in analysis. | |

Ekstrand 2008.

| Methods | RCT. Randomization in blocks of four using a table of random digits. Sequentially labeled envelopes (unclear whether opaque or sealed). Six mo follow‐up, data reported at three and six months. | |

| Participants | 420 Swedish teens, 15‐19 yrs, requesting EC in a local youth clinic in medium‐sized university town in Sweden. Excluded if had a language barrier. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group received requested dose plus extra dose (1.5 mg levonorgestrel taken as a single dose), plus 10 condoms and a leaflet on EC and condom use. Control group received requested dose of EC. | |

| Outcomes | Pregnancy rates, STI rates (unspecified), use of EC, interval between unprotected sex and EC use, frequency of unprotected sex, condom use | |

| Notes | All self‐reported data. Large loss to follow‐up (22% at six months). Not powered to detect differences in pregnancy or STI rates. | |

Gold 2004.

| Methods | RCT (by colored condom chosen from age‐stratified bucket). Correspondence with primary author indicated that participants could not see inside bucket before choosing and were unaware of the color assignments. Two colors, distributed 50:50, inside each bucket. Most clinic staff unlikely to have been able to decipher the color code, method unlikely to have affected randomization. Six mo follow‐up. | |

| Participants | 301 sexually‐active adolescents, aged 15‐20 yrs, in Southwestern Pennsylvania, primarily minority and low‐income. Excluded if using IUD, implant, injectable, if living in foster care or group home, or if had other characteristics which could threaten follow‐up. | |

| Interventions | From study start until April 2000, intervention group received one course Yuzpe regimen 200 mcg ethinyl estradiol plus 2 mg norgestrel, plus an extra dose in case of vomiting, in addition to diphenhydramine. After April 2000, when levonorgestrel only regimens became standard of care, a levonorgestrel‐only regimen was used (two tabs of levonorgestrel 0.75 mg). Participants could obtain two additional courses over six mo period by request, regardless of whether unprotected intercourse had occurred. Participants also received counseling and EC info. Control group received EC on request at the clinic and EC info. | |

| Outcomes | Pregnancy and STI rates (specific STIs not specified), use of EC, interval between unprotected intercourse and EC use, frequency of unprotected intercourse, condom use. | |

| Notes | Large loss to follow‐up (26% at six mo ‐ for reasons other than pregnancy), and loss to follow‐up differential by treatment group (33% in advance provision group, 19% in control group). Not powered to detect differences in pregnancy or STI rates. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

Hazari 2000.

| Methods | RCT. Coded randomization slips prepared off‐site. Three mo follow‐up. | |

| Participants | 200 condom‐using women in Mumbai, India, generally low SES and mostly between the ages of 25‐34 yrs. Excluded if pregnant at baseline as determined by history of last menstrual period and recent unprotected intercourse, vaginal exam, or if required, urine pregnancy test and ultrasonography. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group received one course Yuzpe regimen (50 µg ethinyl estradiol and 0.25 mg levonorgestrel) to be taken in two doses 12 h apart. Replacement pills were provided on request at the clinic. Control group received EC on request at the clinic. Both groups were provided with condoms. | |

| Outcomes | Pregnancy rates, EC use, frequency of unprotected sex. | |

| Notes | Small loss to follow‐up (1%). One pregnancy was missed at baseline, excluded from this review. Article poorly described methodology, participants, and outcomes. Unclear whether differences between groups at baseline. No discussion of sample size. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | |

Hu 2005.

| Methods | RCT. Computer generated simple randomization list. Sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. 12 mo follow‐up. | |

| Participants | 2000 post‐partum women in Shanghai hospital. Excluded if planning on using an IUD or hormonal contraception. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group received three courses of mifepristone (10 mg). Control group received only informatin on EC (but levonorgestrel available in China OTC). All participants received ten condoms. | |

| Outcomes | Pregnancy rates, use of EC, interval between unprotected intercourse and EC use, change in contraceptive methods, condom use. | |

| Notes | Reasonable loss to follow‐up (17%). Originally powered to detect a difference in pregnancy rates, but pregnancy rates much lower than expected, reducing statistical power. Failure to perform intent‐to‐treat analysis (inappropriately excluded those who chose IUD and sterilization). High potential for crossover due to OTC levonorgestrel. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

Jackson 2003.

| Methods | RCT. Cluster randomization by date of discharge from postpartum care, done with random number generator by separate researcher so clinic staff could not predict day's assignment. Data analyzed by individual, re‐evaluated accounting for cluster sampling, no substantial differences. Researchers conducting baseline interviews not masked to group assignment, blinded personnel conducted follow‐up, data entry, and analysis. 12 mo follow‐up. | |

| Participants | 370 post‐partum, low income, racially diverse English‐ or Spanish‐speaking women at public inner‐city hospital in San Francisco. Excluded if major contraindications to estrogen use, post‐partum tubal ligation or partner with vasectomy, employees of Labor and Delivery at the hospital, enrolled in another study, or difficult to reach for follow‐up (lack of a phone, psychiatric disorder, untreated substance abuse, plans for relocation). | |

| Interventions | Intervention group received one course of Yuzpe regimen (eight tabs 0.15 mg levonorgestrel plus 30 µg ethinyl estradiol), educational session, verbal and written instructions. Additional pills available on request. Control group received routine counseling, which may or may not have included a discussion of EC. | |

| Outcomes | Pregnancy rates, use of EC, frequency of unprotected intercourse, change in contraceptive methods, EC knowledge. Except for pregnancy rates, most outcomes can only be included for six‐month follow‐up data, as they were reported separately for the six months prior to the six and twelve‐month follow‐up visits. | |

| Notes | Large loss to follow‐up (31% at 12 months). All self‐reported data. Powered to detect difference in EC use. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | |

Lo 2004.

| Methods | RCT. Computer generated randomization list, blocks of 10. Sequentially numbered opaque, labeled, sealed envelopes. 12 mo follow‐up. | |

| Participants | 1030 women, 18‐45 yrs, attending two Hong Kong clinics using "less effective contraceptive methods" (condoms, spermicide, fertility awareness based methods, withdrawal, or nothing). | |

| Interventions | Intervention group received three courses (two tabs 0.75 mg levonorgestrel), to be taken in two doses 12 h apart, and up to three more courses if needed. Control group received EC on request at clinic. | |

| Outcomes | Pregnancy rates, use of EC, interval between unprotected intercourse and EC use, condom use. | |

| Notes | Small loss to follow‐up (4%). Pregnancy confirmed by pregnancy test. Powered to detect a 10% difference in EC use, not powered to detect a difference in pregnancy rates. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

Raine 2005.

| Methods | RCT. Computer generated randomization sequence assigned participants to one of three groups before December 2001, to one of two groups after December 2001 (clinic access group eliminated because pharmacy access instated in CA). We include only data from intervention and clinic access groups (pre 12/2001). Sequentially numbered treatment boxes with labeled study ID, opened after leaving the clinic. Six mo follow‐up. | |

| Participants | 1228 English or Spanish speaking women, 15‐24 yrs, sexually active in past six mo, largely uninsured and low‐income, at moderately high risk for negative reproductive health outcomes, living in the San Francisco Bay area, attending four California family planning clinics, available for six mo follow‐up. Excluded if pregnant or desiring pregnancy, using hormonal contraception or IUD, or if had unprotected intercourse during the past three days or were requesting EC at enrollment. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group received three courses (two tabs 0.75 mg levonorgestrel), to be taken in two doses 12 h apart, within 72 hours of intercourse. Control group received EC on demand at a clinic. Although EC is generally available at no cost through the clinic, some study participants ineligible for insurance coverage may have had to pay all or some of the cost of EC at two of the four study sites. | |

| Outcomes | Pregnancy rates, STI rates (only information on Chlamydia and HSV2 included because these STIs were confirmed by testing at follow‐up) use of EC, frequency of unprotected intercourse, change in contraceptive methods, condom use. | |

| Notes | Small loss to follow‐up (7% at six months). Some crossover reported. This review excludes information from pharmacy access group as we are interested in comparing advance provision and standard access (before statewide pharmacy access was implemented). Participants differed at baseline by enrollment site, race/ethnicity was linked to enrollment site. Differences controlled for, adjustment did not substantially change results. Powered to detect a difference in pregnancy rates. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

Raymond 2006.

| Methods | RCT. Computer generated randomization scheme in blocks of four, six, and eight. Sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. 12 mo follow‐up. | |

| Participants | 1490 sexually active women, 14‐24 yrs, who did not desire pregnancy and were attending clinics in Nevada and North Carolina. Excluded if using or planning on using sterilization, IUD, hormonal contraception, or if pregnant or breastfeeding in past 6 wks. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group received two courses (two tabs of 0.75 mg levonorgestrel) to be taken together in one dose. More courses provided, attempt to ensure two packages on hand at all times. Control group received EC on request at a clinic. | |

| Outcomes | Pregnancy rates, STI rates (gonorrhea, Chlamydia, trichomoniasis), use of EC, interval between unprotected intercourse and EC use, frequency of unprotected intercourse, change in contraceptive methods, condom use. | |

| Notes | Small loss to follow‐up (6%). Pregnancy and STIs outcomes based primarily on medical chart review plus testing at follow‐up, some women self‐tested at home, sent vaginal samples for confirmation. Powered to detect a difference in pregnancy rates. More intervention participants had STIs at baseline; differences controlled for, adjustment did not substantially change results. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

Schreiber 2009.

| Methods | RCT. Randomization generated in permutated blocks in research unit by computer before recruitment phase. Assignments placed in sealed envelopes in consecutive order. Not clear if envelopes were opaque. 12‐month follow‐up. | |

| Participants | 50 young (14‐19 yrs), English‐speaking women recruited from a hospital post‐partum unit who had delivered a live infant and were planning to parent, who desired to delay pregnancy for at least one year, and who were in good general health. Excluded if had allergy to levonorgestrel, current substance abuse, or plans to relocate outside of Philadelphia. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group received one package of emergency contraceptive pills (Plan B) with routine instructions about EC as well as the chosen primary contraceptive method, a prescription for chosen primary method when applicable, or the first dose of injectable contraception (if injectable contraception was the chosen method). The intervention group had access to additional packages of Plan B upon request. Control group participants were discharged with instructions about their chosen primary contraceptive method and a prescription or first dose for that method. | |

| Outcomes | Pregnancy rates, EC use. | |

| Notes | Large loss to follow‐up (24% at 12 months). All outcomes self‐reported. | |

Schwartz 2008.

| Methods | RCT. Computerized randomization with automatic launching of counseling modules after baseline questionnaire (Research assistant remained unaware of allocation until counseling was completed). follow‐up phone survey by blinded participants. Seven mo follow‐up. | |

| Participants | 446 English‐speaking adult women (18‐45 yrs) from waiting areas of two urgent care clinics in San Francisco who had a phone and no plans to relocate. Excluded if pregnant, had a hysterectomy or tubal ligation, had an IUD, had a partner with vasectomy, or a lesbian. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group received a single package of two 0.75 mg levonorgestrel pills and computerized conseling on EC. Control group received computerized counseling about pre‐conception folate and a sample of folate. | |

| Outcomes | Pregnancy rates, use of EC, unprotected sex in last six months, condom use. | |

| Notes | Large loss to follow‐up (41% at seven months). All outcomes self‐reported. Powered to detect a difference in use of EC. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Blanchard 2003 | Not a randomized controlled trial. |

| Ellertson 2001 | Proportion of women in each treatment arm who became pregnant during follow‐up not clearly reported; raw data unavailable |

| Endres 2000 | Not a randomized controlled trial. |

| Glasier 1998 | Not a randomized controlled trial. |

| Glasier 2004 | Not a randomized controlled trial. |

| Golden 2004 | Randomized controlled trial of partner notification, not advance provision. Collected qualitative data on EC interest. |

| Golden 2009 | Intervention was advanced prescription, not advanced provision of emergency contraception |

| Harper 2005 | Based on same data as Raine 2005, restricted to adolescents. |

| Larsson 2006 | Not a randomized controlled trial. |

| London 2006 | Review of Harper 2005. |

| Lovvorn 2000 | Not a randomized controlled trial. |

| Ng 2003 | Did not collect pregnancy data. |

| Petersen 2007 | Did not collect pregnancy data. |

| Raine 2000 | Not a randomized controlled trial. |

| Rocca 2007 | Derivative of Raine 2005, did not assess pregnancy as an outcome |

| Sander 2009 | Derivative of Raymond 2006, used only data from control arm. |

| Skibiak 1999 | Not a randomized controlled trial. |

| Stehle 1999 | Appears on PubMed as a randomized controlled trial, but actually a review of Glasier 1998 |

| Teal 2008 | Not a randomized controlled trial (alternate assignment). |

| Walker 2006 | Intervention is not advance provision of emergency contraception |

| Walsh 2006 | Not conducted as a randomized controlled trial since no attempt was made to follow‐up 70% of randomized participants. |

Contributions of authors

Chelsea Polis and Kate Schaffer generated drafts of the protocol, and all authors provided input. Chelsea Polis drafted the data abstraction sheets and conducted the literature search with input from all authors. Chelsea Polis and David Grimes abstracted and entered the data for the original study and for the November 2009 update. All authors provided input to the analysis and writing.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Ibis Reproductive Health, USA.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

Two review co‐authors were also co‐authors of included studies (Cynthia Harper: Raine 2005, and Anna Glasier: Lo 2004 and Hu 2005).

Edited (no change to conclusions), comment added to review

References

References to studies included in this review

Belzer 2005 {published data only}

- Belzer M, Sanchez K, Olson J, Jacobs AM, Tucker D. Advance supply of emergency contraception: A randomized trial in adolescent mothers. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2005;18(5):347‐354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ekstrand 2008 {published and unpublished data}

- Ekstrand M, Larsson M, Darj E, Tyden T. Advance provision of emergency contraceptive pills reduces treatment delay: a randomized controlled trial among Swedish teenage girls. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica 2008;87(3):354‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gold 2004 {published and unpublished data}

- Gold MA, Woldford JE, Smith KA, Parker AM. The effects of advance provision of emergency contraception on adolescent women's sexual and contraceptive behaviors. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2004;17(2):87‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hazari 2000 {published data only}

- Hazari K. Use of emergency contraception by women as a back‐up method. Health and Population 2000;23(3):115‐122. [Google Scholar]

Hu 2005 {published data only}

- Hu X, Cheng L, Hua X, Glasier A. Advanced provision of emergency contraception to postnatal women in China makes no difference in abortion rates: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2005;72(2):111‐116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jackson 2003 {published data only}

- Jackson RA, Schwarz EB, Freedman L, Darney P. Advance supply of emergency contraception: effect on use and usual contraception ‐ a randomized trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2003;102(1):8‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lo 2004 {published data only}

- Lo SST, Fan SYS, Ho PC, Glasier AF. Effect of advanced provision of emergency contraception on women's contraceptive behavior: a randomized controlled trial. Human Reproduction 2004;19(10):2404‐2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Raine 2005 {published and unpublished data}

- Raine TR, Harper CC, Rocca CH, Fischer R, Padian N, Klausner JD, et al. Direct access to emergency contraception through pharmacies and effect on unintended pregnancy and STIs: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 2005;293(1):54‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Raymond 2006 {published data only}

- Baecher L, Weaver MA, Raymond EG. Increased access to emergency contraception: why it may fail. Human Reproduction 2009;1(1):1‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond EG, Stewart F, Weaver M, Monteith C, Pol B. Randomized trial to evaluate the impact of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2006;108(5):1098‐106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond EG, Weaver MA. Effect of an emergency contraceptive pill intervention on pregnancy risk behavior. Contraception 2008;77(5):333‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver MS, Raymond EG, Sander PM. Attitude and behavior effects in a randomized trial of increased access to emergency contraception. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2009;113(1):107‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schreiber 2009 {unpublished data only}

Schwartz 2008 {published and unpublished data}

- Schwarz EB, Gerbert B, Gonzales R. Computer‐assisted Provision of Emergency Contraception: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2008;23(6):794‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Blanchard 2003 {published data only}

- Blanchard K, Bungay H, Furedi A, Sanders L. Evaluation of an emergency contraception advance provision service. Contraception 2003;67(5):343‐348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ellertson 2001 {published and unpublished data}

- Ellertson C, Ambardekar S, Hedley A, Coyaji K, Trussell J, Blanchard K. Emergency contraception: randomized comparison of advance provision and information only. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2001;98(4):570‐575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Endres 2000 {published data only}

- Endres LK, Beshara M, Sondheimer S. Experience with self‐administered emergency contraception in a low‐income, inner‐city family planning program. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 2000;45(10):827‐830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Glasier 1998 {published data only}

- Glasier A, Baird D. The effects of self‐administering emergency contraception. New England Journal of Medicine 1998;339(1):1‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Glasier 2004 {published data only}

- Glasier A, Fairhurst K, Wyke S, Ziebland S, Seaman P, Walker J, et al. Advanced provision of emergency contraception does not reduce abortion rates. Contraception 2004;69(5):361‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Golden 2004 {published data only}

- Golden MR, Whittington WLH, Handsfield HH, Clark A, Malinsky C, Helmers JR, et al. Failure of family‐planning referral and high interest in advanced provision emergency contraception among women contacted for STD partner notification. Contraception 2004;69(3):241‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Golden 2009 {unpublished data only}

- Golden MR, Brewer DD, Hogben M, Malinski C, Golding A, Holmes KK. Advanced provision emergency contraception among women receiving partner notification services for Gonorrhea or Chlamydial infection: a randomized controlled trial and meta‐analysis. Unpublished manuscript.

Harper 2005 {published data only}

- Harper CC, Cheong M, Rocca CH, Darney PD, Raine TR. The effect of increased access to emergency contraception among young adolescents. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2005;106(3):483‐491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Larsson 2006 {published data only}

- Larsson M, Aneblom G, Eurenius K, Westerling R, Tyden T. Limited impact of an intervention regarding emergency contraceptive pills in Sweden ‐ repeated surveys among abortion applicants. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2006;11(4):270‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

London 2006 {published data only}

- London S. Easy access to EC increases teenagers' use, but does not lead to risky behavior. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 2006;38(1):55‐6. [Google Scholar]

Lovvorn 2000 {published data only}

- Lovvorn A, Nerquaye‐Tetteh J, Glover EK, Amankwah‐Poku A, Hays M, Raymond E. Provision of emergency contraceptive pills to spermicide users in Ghana. Contraception 2000;61(4):287‐293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ng 2003 {published and unpublished data}

- Ng EPS, Damus K, Bruck L, MacIsaac L. Advance provision of levonorgestrel‐only emergency contraception versus provision. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003; Vol. 101:13S.

Petersen 2007 {published and unpublished data}

- Petersen R, Albright JB, Garrett JM, Curtis KM. Acceptance and use of emergency contraception with standardized counseling intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2007;75(2):119‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Raine 2000 {published data only}

- Raine T, Harper C, Leon K, Darney P. Emergency contraception: advance provision in a young, high‐risk clinic population. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;96(1):1‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rocca 2007 {published data only}

- Rocca CH, Schwarz EB, Stewart FH, Darney PD, Raine TR, Harper CC. Beyond access: acceptability, use and nonuse of emergency contraception among young women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2007;196(1):29.e1‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sander 2009 {published data only}

- Sander PM, Raymond EG, Weaver MA. Emergency contraceptive use as a marker of future risky sex, pregnancy, and sexually transmitted infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201(146):e1‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Skibiak 1999 {unpublished data only}

- Skibiak JP, Ahmed Y, Ketata M. Testing strategies to improve access to emergency contraception pills: prescription vs. prophylactic distribution. Nairobi: Population Council 1999.

Stehle 1999 {published data only}

- Stehle K. The effects of self‐administering emergency contraception. Journal of Nurse‐Midwifery 1999;44(1):82‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Teal 2008 {unpublished data only}

- Teal S, Sheeder J, Stevens‐Simon C. To have or to hold: use patterns and pregnancy rates in adolescent mothers given advance ECPs or ECP prescriptions. North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2008.

Walker 2006 {published and unpublished data}

- Walker D, Gutierrez JP, Torres P, Bertozzi SM. HIV prevention in Mexican schools: prospective randomised evaluation of intervention. British Medical Journal 2006;332(7551):1189‐94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Walsh 2006 {published data only}

- Walsh TL, Frezieres RG. Patterns of emergency contraception use by age and ethnicity from a randomized trial comparing advance provision and information only. Contraception 2006;74(2):110‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Alderson 2004

- Alderson P, Green S, Higgins JPT, editors. Cochrane Reviewer's Handbook 4.2.2 [updated March 2004]. http://www.cochrane.org/resources/handbook/hbook.htm (accessed August 10, 2004).

Arowojolu 2002

- Arowojolu AO, Okewole LA, Adekunle AO. Comparative evaluation of the effectiveness and safety of two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception in Nigerians. Contraception 2002;66(4):269‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Baecher 2009

- Baecher L, Weaver MA, Raymond EG. Increased access to emergency contraception: why it may fail. Human Reproduction 2009;1(1):1‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cheng 2008

- Cheng L, Gulmezoglu AM, Piaggio G, Ezcurra E, Look PF. Interventions for emergency contraception. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 2, DOI 10.1002/14651858.CD001324.pub3. [PUBMED: 18425871] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DerSimonian 1986

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐Analysis in Clinical Trials. Controlled Clinical Trials 1986;7(3):177‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fu 1998

- Fu H, Darroch JE, Henshaw SK, Kolb E. Measuring the extent of abortion underreporting in the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Family Planning Perspectives 1998;30(3):128‐33, 138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Galvao 2005

- Galvao LW, Oliveira LC, Diaz J, Kim DJ, Marchi N, Dam J, et al. Effectiveness of female and male condoms in preventing exposure to semen during vaginal intercourse: a randomized trial. Contraception 2005;71(2):130‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gold 1997

- Gold MA, Schein A, Coupey SM. Emergency contraception: a national survey of adolescent health experts. Family Planning Perspectives 1997;29(1):15‐9, 24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Golden 2001

- Golden NH, Siegel WM, Fisher M, Schneider M, Quijano E, Suss A, et al. Emergency contraception: pediatricians' knowledge, attitudes and opinions. Pediatrics 2001;107(2):287‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goulard 2006

- Goulard H, Moreeau C, Gilbert F, Job‐Spira N, Bajos N. Contraceptive failures and determinants of emergency contraception use. Contraception 2006;74(3):208‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Helmerhorst 2001

- Helmerhorst F, Oel C, Kulier R (on behalf of the Editorial Team). Cochrane Fertility Regulation Group. The Cochrane Library. Oxford: Update Software, 2006, issue 2.

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. British Medical Journal 2003;327(7414):557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Juni 2002

- Juni P, Holenstein F, Sterne J, Bartlett C, Egger M. Direction and impact of language bias in meta‐analyses of controlled trials: empirical study. International Journal of Epidemiology 2002;31(1):115‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Landry 2006

- Landry P, Iorillo D, Darioli R, Burnier M, Genton B. Do travelers really take their mefloquine malaria chemoprophylaxis? Esimation of adherence by an electronic pillbox. Journal of Travel Medicine 2006;13(1):8‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lawson 1998

- Lawson ML, Maculuso M, Bloom A, Hortin G, Hammond KR, Blackwell R. Objective markers of condom failure. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 1998;25(8):427‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Macaluso 2003

- Macaluso M, Lawson ML, Hortin G, Duerr A, Hammond KR, Blackwell R, et al. Efficacy of the female condom as a barrier to semen during intercourse. American Journal of Epidemiology 2003;157(4):289‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moher 2000

- Moher D, Pham B, Klassen TP, Schulz KF, Berlin JF, Jadad AR, et al. What contributions do languages other than English make on the results of meta‐analyses?. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2000;53(9):964‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moreau 2005

- Moreau C, Bouyer J, Goulard H, Bajos N. The remaining barriers to the use of emergency contraception: perception of pregnancy risk by women undergoing induced abortions. Contraception 2005;71(3):202‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Raymond 2004

- Raymond E, Taylor D, Trussell J, Steiner MJ. Minimum effectiveness of the levonorgestrel regimen of emergency contraception. Contraception 2004;69(1):79‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Raymond 2008

- Raymond EG, Weaver MA. Effect of an emergency contraceptive pill intervention on pregnancy risk behavior. Contraception 2008;77(5):333‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rogers 2005

- Rogers SM, Willis G, Al‐Tayyib A, Villarroel MA, Turner CF Ganapthi L, et al. Audio computer assisted interviewing to measure HIV risk behaviors in a clinic population. Sexually transmitted infections 2005;81(6):501‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schulz 2006

- Schulz KF, Grimes DA. The Lancet handbook of essential concepts in clinical research. London: Elsevier, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Sherman 2001

- Sherman CA, Harvey SM, Beckman LJ, Petitti DB. Emergency contraception: knowledge and attitudes of health care providers in a health maintenence organization. Women's Health Issues 2001;11(5):448‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sorensen 2000

- Sorensen MB, Pedersen BL, Nyrnberg LE. Differences between users and non‐users of emergency contraception after a recognized unprotected intercourse. Contraception 2000;62(1):1‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Steiner 1996

- Steiner M, Dominik R, Trussell J, Hertz‐Picciott I. Measuring contraceptive effectiveness: a conceptual framework. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1996;88(3 suppl):24S‐30S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stuart 2009

- Stuart GS, Grimes DA. Social desirabilty bias in family planning studies: a neglected problem. Contraception 2009;80(2):108‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Task Force 1998