I'll imitate the pities of old surgeons

To this lost limb, who ere they show their art

Cast one asleep, then cut the diseased part.

Thomas Middleton (1570-1627), Women beware Women

Before the advent of general anaesthesia, it is generally believed, a patient undergoing an operation could have expected little in the way of support other than from the bottle or from an ability to “bite the bullet.” But there is compelling evidence of an earlier age of anaesthesia. Descriptions of anaesthetics based on mixtures of medicinal herbs have been found in manuscripts dating from before Roman times until well into the Middle Ages. Most originated in regions of southern Europe where the relevant herbs grew naturally. A typical one, dated 800 AD, from the Benedictine monastery at Monte Cassino in southern Italy, used a mixture of opium, henbane, mulberry juice, lettuce, hemlock, mandragora, and ivy.1

There is no evidence to suggest that similar recipes existed in the British Isles at that time.2 However, in 1992, an extensive study succeeded in identifying a large number of similar recipes in late medieval (12th-15th century) English manuscripts.3 All identified the anaesthetic, a drink, by the name dwale. A typical manuscript (fig 1), translated into modern English, reads:

Summary points

Although general anaesthesia is little more than 150 years old, the use of medicinal herbs to render patients unconscious before surgery goes back to Roman times

Recent studies have identified a large number of recipes for a herbal anaesthetic known as dwale, written in medieval English

These include two groups of ingredients, the harmless and ineffectual—bile, lettuce, vinegar, and bryony root—and the powerful and dangerous—hemlock, opium, and henbane

In spite of its dangers, dwale was widely known about, and would have been administered by ordinary housewives, caring for loved ones

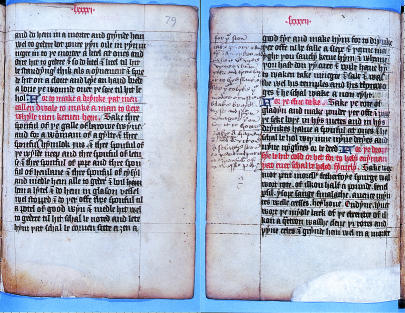

Figure 1.

A typical dwale manuscript. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library (MS Dd.6.29, f79r-v)

“How to make a drink that men call dwale to make a man sleep whilst men cut him: take three spoonfuls of the gall [bile] of a barrow swine [boar] for a man, and for a woman of a gilt [sow], three spoonfuls of hemlock juice, three spoonfuls of wild neep [bryony], three spoonfuls of lettuce, three spoonfuls of pape [opium], three spoonfuls of henbane, and three spoonfuls of eysyl [vinegar], and mix them all together and boil them a little and put them in a glass vessel well stopped and put thereof three spoonfuls into a potel of good wine and mix it well together.

“When it is needed, let him that shall be cut sit against a good fire and make him drink thereof until he fall asleep and then you may safely cut him, and when you have done your cure and will have him awake, take vinegar and salt and wash well his temples and his cheekbones and he shall awake immediately.”

This paper discusses the ingredients in the dwale recipe, the recipe's likely origins, and the possible circumstances and consequences of its use.

Ingredients

In addition to alcohol, the ingredients in dwale are, in order of their listing, bile, hemlock, bryony, lettuce, opium, henbane, and vinegar.

Bile

Although Shakespeare's Macbeth includes “gall of goat” inthe witches' brew, the use of animal matter in herbal recipes was unusual. Bile, however, was often mixed with fat in the preparation of ointments to aid the emulsification and absorption of ingredients, and it might have been included in dwale for the same reason.3

Hemlock

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk.

Keats, Ode to a Nightingale

Hemlock, Conium maculatum, (fig 2) is a tall umbelliferous plant with a sinister reputation, thanks to the presence in its juice of a number of coniine related alkaloids which work by blocking the nicotinic actions of the autonomic neurotransmitter acetylcholine.4 It was the official poison of ancient Greece, and no better account exists of hemlock's ability to induce a motor paralysis followed by a sensory one than that given by an assistant present at the suicide of the philosopher Socrates: “When he said that his legs were heavy, [Socrates] lay down on his back, and he who gave him the poison ... examined his feet and legs: and then having pressed his foot hard, he asked if he felt it: he said that he did not. And after this he pressed his thighs; and thus going higher, he showed us that [Socrates] was growing cold and stiff.”5

Figure 2.

Conium maculatum (poison hemlock). The reddish-brown stem markings, said to be the brand of Cain, are characteristic

The fact that unconsciousness comes late with hemlock poisoning suggests that Keats's experience was not personal. Because it induces respiratory paralysis, hemlock still causes occasional fatalities,6 and it is fascinating to consider whether coniine or related alkaloids could have found a place in modern anaesthesia.

Bryony

Wild neep is one of several synonyms for Bryonia dioica, a native plant of the English hedgerow whose fleshy tuberous roots were once used as a powerful purgative. Bryony's presence in dwale is likely to be the result of another herb's absence.

Mandragora officinarum, the mandrake, grows naturally all over southern Europe and the Middle East, and was, after the opium poppy, the commonest herb used in Mediterranean recipes, thanks to the presence, in its root, of a number of hyoscine related alkaloids. Like atropine, hyoscine blocks the muscarinic effects of acetylcholine, but unlike atropine it readily crosses the blood-brain barrier. In consequence, it has the ability to produce not only drowsiness but also hallucinations, particularly in elderly people—a phenomenon well known to anaesthetists and a possible explanation for witchcraft.7

Mandrake owed its popularity, down the ages, to the resemblance of its root to the shape of a man, causing it to be highly prized as a fertility symbol. In northern Europe, however, mandrake does not grow naturally, so here bryony roots, which have a similarly fleshy appearance (fig 3), were dug up from hedgerows instead and sold to gullible people.8,9Bryony is still used today by practitioners of black magic as a mandrake substitute,10 and it seems likely that, during translation of the recipe from an (unknown) Latin text, a similar substitution must have occurred.

Figure 3.

Mandrakes true and false. Left: Mandragora officinarum, the “true” mandrake; right: Bryonia dioica, known as wild neep or white bryony, and as the false, or English, mandrake (one “leg” has accidentally been amputated)

Lettuce

Lactucarium, the dried juice of the wild lettuce, Lactuca virosa, has been associated with a mild sedative action for centuries and is a major component of herbal sedatives today. There is, however, little or no scientific evidence to justify this association.11 Folk tales which associate the garden lettuce Lactuca sativa with sleep can more reasonably be attributed to the appetite of Beatrix Potter's rabbits.

Opium

The pain killing power of the opium or white poppy, Papaver somniferum, was known to the earliest of civilisations, and although only one of the dwale recipes actually specifies it by name, it is likely that this was the poppy intended for use.

Henbane

Hyoscyamus niger, henbane, is, like mandrake, a member of a huge botanical order, the Solanaceae, and like mandrake is capable of inducing a profound and long lasting unconsciousness, thanks to its hyoscine content. Unlike mandrake, however, henbane grows naturally in the British Isles.

Although hemlock never found a place in modern medicine, omnopon and hyoscine, the chief alkaloids in opium and henbane, respectively, did so early this century, both in anaesthesia and, under the name of twilight sleep, in psychiatry and obstetrics.12

Vinegar

Eysyl was one of several varieties of vinegar in common use during medieval times.13 It had long been used to revive unconscious people and is also mentioned in the dwale recipe as a way of rousing the patient after the operation. According to the scriptures, vinegar, rather than the more usual mandrake wine, was offered to Christ on the cross.12

Discussion

A Troy spoon (the standard measurement throughout the period under discussion) held a volume of 11.6 ml.14 The recipe calls for three spoonfuls (34.8 ml) of each ingredient (243 ml in total) to be mixed, and for three spoonfuls of this mixture (3.5 ml of each ingredient) to be added to a potel (half gallon)14 of wine.

Dangers

The seven ingredients in the dwale recipe can be divided into two broad groups, those in the first group being harmless and ineffectual (bile, lettuce, vinegar, and bryony root), and those in the second being powerful and dangerous (hemlock, opium, and henbane). Ingesting as little as 1 ml of hemlock juice can prove fatal15; 3.5 ml opium (normal concentration 4-12% morphine alkaloids) would come close to, or exceed, the fatal dose of around 300 mg, and a similar volume of henbane (normally 0.25-0.5% concentration) would contain 8.75-17.5 mg of hyoscine alkaloids, enough to kill a child.15 The alcohol in the wine itself cannot be ignored.

However, dwale might not have been quite as dangerous as would at first sight appear. Medicinal herbs grown in northern countries are less potent than those grown in sunnier regions. As their potency is greatest when herbs are freshly collected, much would have been lost in the boiling and storage that the recipe calls for.

Most importantly, the recipe only asks him that “shall be cut” to drink until he falls asleep. A potel (2.276 litres) is the equivalent today of three bottles of wine. It seems most unlikely that the patient would have drunk this entire amount, particularly as the presence of bile and vinegar in the mixture would have given it a bitter taste. The amount consumed would have been enormously variable, and it is this variability in dose that would have made dwale so dangerously unpredictable.

Knowledge

In spite of the dangers, there can be little doubt that dwale was widely known about. The recipes are widely distributed (well over 50 have been identified to date) and we must therefore consider how they might have been used. A clue is to be found in Chaucer's reference, in the Reeve's tale, to a medieval “ménage à trois”:

To bedde went the daughter right soon,

To bedde goth Aleyn and also John,

There was no more—they needed no dwale.

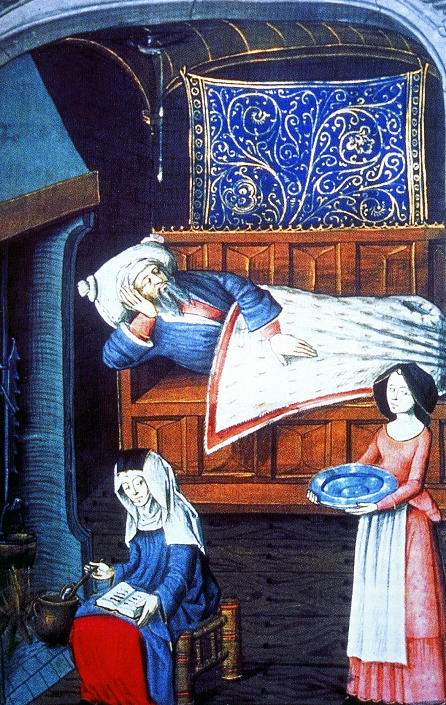

During medieval times, it was to the monastery and almshouse that poor people turned for healing. The better off (and more literate) middle classes received treatment in their own homes, and dwale recipes are found not in medical or religious texts but rather in domestic remedy books—small notebooks of household hints, such as the one being consulted in figure 4.16 Who then might have administered these early anaesthetics? It certainly would not have been the surgeons themselves, for in spite of Thomas Middleton's lines, medieval surgeons only ever referred to “sleeping medicines” to warn against their use.3,12 Almost certainly it would have been ordinary housewives, caring for loved ones who had, perhaps, returned home injured from the wars. How many would in due course have had cause to regret their actions we can only guess.

For to make a drink that men call dwale to make a man sleep while men carve him:

Take three spoonfuls of the gall of a barrow swyne

and for a woman of a gylte, three

spoonfuls of hemlock juice, three spoonfuls of

ye wild neep, three spoonfuls of letuce,

three spoonfuls of pape, three spoonfuls

of henbane, and three spoonfuls of eysyl

and mix them all together and boil

them a little and put them in a glass vessel

well stopped and put thereof three spoonfuls into

a potel of good wine and mix it well

together. When it is needed, let

him that shall be carved sit against a

good fire and make him to drink

thereof until he fall asleep and then may

right you safely carve him, and when

you have done the cure and would have him

to awaken, take vinegar and salt and

wash well his temples and his cheekbones

and he shall awake from rest.

Figure 4.

The medieval housewife was expected to possess the skills of both herbalist and apothecary (c1470). Reproduced by kind permission of the British Library (Royal Ms 15, DI, f18 recto)

Sleeping drinks went out of fashion before the arrival of the printed word but were not completely forgotten about, and their legacy survives today in the role they came to play in Elizabethan drama. Perhaps the most ingenious example is the explanation given by Barabas, in Christopher Marlowe's play The Jew of Malta, of how he managed to escape from captivity:

I drank of poppy and cold mandrake juice

And being asleep, belike they thought me dead,

And threw me over the walls.

Barabas eventually regained consciousness, but the outlook for those who took “drowsy syrups” in real life would have been less certain. Although these recipes were rightly abandoned many centuries ago, they can teach us much, even today. They remind us, for example, of the links that once existed between medicine and magic; that, as Shakespeare tells us, “in poison there is physic”; and that much medical advance in the 20th century has come not from new drugs but rather from our ability to measure and administer old ones accurately. At the dawning of a new millennium they serve to remind us, once again, of the enormous debt we owe to the past.

Acknowledgments

I thank Professor L E Voigts for first bringing the dwale recipes to my attention.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Keys TE. The history of surgical anaesthesia. New York: Schuman; 1945. p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cameron ML. Anglo-Saxon medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1993. p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voigts LE, Hudson RP. A drynke called dwale: a surgical anaesthetic from late medieval England. In: Campbell S, Hall B, Klausner D, editors. . Health, disease and healing in medieval culture. New York: St Martin's Press; 1992. pp. 34–56. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman WC, Sanghvi IS. Pharmacological actions of hemlock (Conium maculatum) alkaloids. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1963;15:1–25. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1963.tb12738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis ES. Ancient anodynes. London: Heinemann; 1946. p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drummer OH, Roberts AN, Bedford PJ, Crump KL, Phelan MH. Three deaths from hemlock poisoning. Med J Aust. 1995;162:592–593. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb138553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann J. Murder, magic and medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vicary R. Dictionary of plant lore. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 393–394. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reader's Digest. Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain. London: Reader's Digest Association; 1981. p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huson P. Mastering witchcraft. London: Rupert Hart-Davis; 1970. p. 146. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grieve M. A modern herbal. London: Jonathan Cape; 1931. 2:476-7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter AJ. Narcosis and nightshade. BMJ. 1996;313:1630–1632. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7072.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray JAH. New English dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1897. p. 488. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connor RD. The weights and measures of England. London: HMSO; 1987. p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dreisbach RH, Robertson WO. Handbook of poisoning. Prentice-Hall International, 1987. p. 499. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rawcliffe C. Medicine and society in later medieval England. Stroud: Alan Sutton; 1997. p. 184. [Google Scholar]