Abstract

In recent years, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have emerged as promising anti-cancer therapeutic agents with several having already received market approval for the treatment of solid tumor and hematological malignancies. As ADC technology continues to improve and the range of indications treatable by ADCs increases, the repertoire of target antigens has expanded and will undoubtedly continue to grow. G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are well-characterized therapeutic targets implicated in many human pathologies, including cancer, and represent a promising emerging target of ADCs. In this review, we will discuss the past and present therapeutic targeting of GPCRs and describe ADCs as therapeutic modalities. Moreover, we will summarize the status of existing preclinical and clinical GPCR-targeted ADCs and address the potential of GPCRs as novel targets for future ADC development.

Keywords: antibody, drug conjugate, G protein-coupled receptor, linker, payload

1. Introduction

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) have long been successful targets of therapeutic agents, accounting for approximately 35% of FDA-approved drugs [1]. Traditional strategies of targeting GPCRs have largely been confined to small molecule inhibitors wherein significant progress has been made in the advancement of crystallography, rational drug design, and ligand screening [2, 3]. Notably, biologic agents including peptides, metabolites, and antibody-based therapeutics are expanding classes of therapeutic agents targeting GPCRs [3]. Antibody-based therapeutics in general have garnered significant attention as anti-cancer agents due to their ability to specifically target tumors while sparing normal tissues [4].

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), a flavor of antibody-based therapeutics, are one of the fastest growing classes of drugs for cancer therapy. ADCs are monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) with chemically conjugated cytotoxic payloads that target antigens expressed at much higher levels on cancer cells compared to normal cells to specifically deliver drugs to tumor sites. Accordingly, ADCs improve the therapeutic index (TI) of potent cytotoxic agents by restricting their delivery to targeted tumor sites and minimizing off-target effects to normal tissues. There are currently 12 FDA-approved ADCs with dozens more in different stages of preclinical and clinical development [5]. Remarkably, 8 ADCs have received approval in the last 5 years, demonstrating the rapidly developing nature of this field. ADCs are currently approved for both hematological and solid tumors with indications including acute myeloid leukemia (AML), acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), multiple myeloma (MM), HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancers, and gastric cancer, among others [5]. The application of ADCs beyond oncologic diseases is another ongoing area of research [6-8].

Since the first ADC reached the market in 2000, extensive improvements in ADC technology have been made to increase efficacy and safety. As ADC development continues, the range of targeted antigens expands in parallel. Not surprisingly, GPCRs are emerging targets of ADCs with the potential to greatly expand the current landscape of ADC target antigens. At present, there are 7 GPCRs targeted by ADCs, two of which have reached Phase I clinical trials. The focus of this review is to detail the design and efficacy of these GPCR-targeted ADCs, comprising a novel class of promising anti-cancer therapeutics.

2. GPCRs as therapeutic targets

GPCRs represent the largest family of membrane proteins, are responsible for a wealth of physiological functions, and are characterized by the presence of a 7 transmembrane domain [9]. There are approximately 800 GPCRs encoded by the human genome, subdivided into 5 main families based on structural homology: rhodopsin (class A), secretin (class B), glutamate (class C), adhesion, and Frizzled/Taste2 [10]. Nearly 350 of these GPCRs are considered non-olfactory and druggable [11]. Due to their widespread expression on the plasma membrane as well as their role in numerous physiological processes, GPCRs are the most frequently targeted proteins. Yet as of 2021 only 165 have been validated as drug targets [3]. Thus, there remains significant research opportunities to expand upon the existing repertoire of GPCR therapeutics.

To date, the majority of indications treatable by GPCR therapeutics have been non-oncologic, focusing on diseases of the central nervous system, obesity, and Alzheimer’s disease [12]. This is in part because up until lately, there has been limited knowledge of GPCR expression in cancer. Recent analyses of patient genomic data (i.e. bulk and single-cell RNA-seq), however, have identified GPCR cancer-specific biomarkers that may serve as unique therapeutic targets [13]. Mutations in GPCRs have also been found in nearly 20% of human cancers, though not all are drivers of disease [14]. Alterations have been reported in thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR), Frizzled (FZD)-related receptor Smoothened homologue (SMO), and members of the adhesion family of GPCRs. The potential use of therapies such as mAbs to selectively target mutated GPCRs would likely depend on the accessibility of the mutation (i.e. extracellular domain, ECD) and may limit on-target, off-tumor toxicity. As cancer-specific expression patterns have yet to be fully exploited, GPCR targeting for oncologic indications is still largely unexplored.

Traditionally, therapeutics targeting GPCRs have been confined to small-molecule compounds including synthetic organic, inorganic, and natural products. These agents occupy ~64% of all GPCR-targeted therapeutics, yet the proportion of biologics continues to grow [3]. Antibody-based therapeutics are a subclass of biologic agents that include ADCs, nanobodies, bispecific antibodies (bsAbs), and chimeric antigen receptor-T cells [15]. Antibodies offer unique advantages over small molecule agents including increased target affinity, specificity, and other kinetic advantages, though they are not without their own difficulties. GPCR localization in the plasma membrane, structural/functional interfamily diversity, and difficulties in protein expression/isolation all pose unique challenges for GPCR antibody development [16]. In part, these issues have been ameliorated via breakthroughs in antibody discovery and functional screening such as new generation detergents, methods for the detection of GPCR-expressing cell lines, and GPCR stabilization [15].

Currently, there are 3 FDA-approved mAbs targeting GPCRs or their associated ligands for non-oncologic indications: anti-CCR4 mAb (mogamulizumab), anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) type 1 receptor mAb (erenumab), and anti-CGRP mAb (eptinezumab) [3, 15]. In addition to market-approved mAbs, there are several in the development pipeline. As of 2019, it was estimated that at least 146 GPCR-targeted mAbs were in discovery stages with an additional 45 in clinical trials [15]. As GPCR antibody-based therapeutics continue to expand and come onto the market, the modality of approved agents will likely reach beyond mAbs to include bsAbs, nanobodies, ADCs, and more. ADCs, specifically, are the focus for the remainder of this review.

3. Antibody-drug conjugates

The first ADC to reach the market, gemtuzumab ozagamicin, was approved by the FDA in 2000 for the treatment of relapsed or refractory CD33-positive AML. Since 2000, 11 more ADCs have obtained FDA-approval; targeting HER2, trop2, nectin4, and tissue factor for treatment of solid tumors and CD19, CD22, CD30, CD33, CD79B, and B-cell maturation antigen for combatting hematological malignancies [5]. Since their inception, dramatic advances in linker technology and ADC optimization have significantly enhanced ADC therapeutic indices and safety profiles. As a result, there are currently several ADC candidates being investigated in various stages of preclinical development and clinical trials for a wide range of oncologic and non-oncologic indications [5]. For an ADC to reach clinical trials it must demonstrate sufficient efficacy and tolerability. However, there are many crucial decisions to be made during the development stage including the choice of target antigen, antibody, linker technology, and payload.

3.1. ADC structure and function

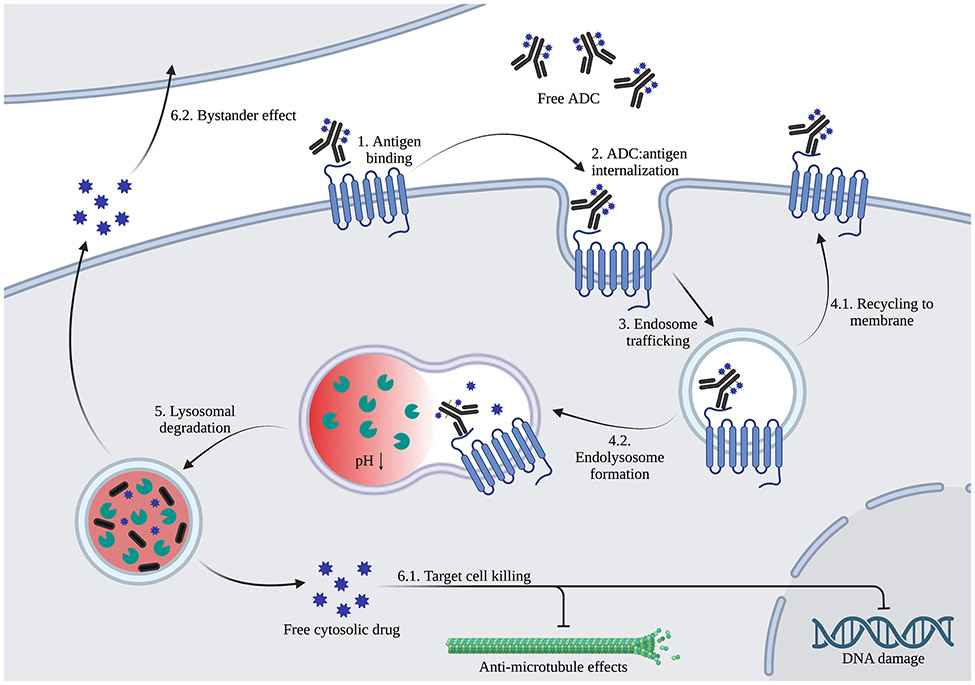

For clinically approved and preclinical ADCs, there is expansive diversity in ADC structure. The core structure of ADCs, which consists of a mAb backbone, linker moiety, and cytotoxic payload, is illustrated in Figure 1. Generally, ADC linkers are non-cleavable or cleavable, though the mechanism of cleavage can vary considerably. Those most utilized cleavable linkers are protease-, acid-, glutathione-, or enzyme-based (i.e. cathepsin B) [17]. Among antibody backbones, IgG1 subtypes are frequently used in ADC development due to their high serum stability and ability to potently activate immune effector systems such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and the complement system [18]. Cytotoxic payloads include microtubule-targeting agents, such as auristatins and maytansinoids; topoisomerase I inhibitors, such as camptothecin and deruxtecan; and DNA-damaging agents, such as duocarmycins, calicheamicins and pyrrolobenzodiazepines [18, 19]. In addition to the type of payload conjugated to ADCs, there is also variation in the ratio of linker-drug moieties conjugated to each mAb, or drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR), which typically falls in the range of 2-8. Linker-antibody conjugation strategies vary among ADCs, with 4 FDA-approved ADCs utilizing lysine terminal α-amino groups and the remaining 8 utilizing cysteine thiol groups to conjugate mAb to cytotoxic payload [20]. More recent conjugation strategies have emerged to enhance site specificity and ADC homogeneity, including the incorporation of non-canonical amino acids, enzymatic amino acid modification (e.g. transglutaminase-based), and glycan modification in the CH2 region of IgG antibodies [21]. Upon administration, ADCs bind to their target antigen, internalize into the cell and are trafficked for lysosomal degradation, resulting in release of the cytotoxic drug and killing of the target cell (Figure 2). Notably, there are instances where the bound ADC-antigen complex is recycled to the membrane after internalization [22]. Additionally, non-polar payloads may diffuse out of the cell and non-specifically kill surrounding cells, deemed the bystander effect. The combined effects of mAb, linker, payload, and DAR all dramatically influence mechanistic action and efficacy of ADCs. Importantly, ADC efficacy also hinges on its targeting an optimal antigen.

Figure 1. ADC structural composition.

Figure 2. ADC generalized mechanism of action.

ADC binds target antigen on cell surface (1) and internalizes (2) to endosomes (3). The endosome either recycles back to the plasma membrane (4.1) or fuses with lysosomes (4.2). Low pH and enzymatic activity within the lysosome cause ADC drug release via linker cleavage and/or degradation (5), resulting in target tumor cell-killing (6.1) and potential diffusion from target cells to kill bystander cells (6.2).

3.2. GPCRs as ADC tumor antigens

Optimal antigen choice requires high extracellular surface expression on tumors and absent or significantly lower expression on normal cells. Therefore, target selection is oftentimes easier for hematological malignancies where lineage-specific antigens are exclusively expressed on target cells [23]. In addition to differential expression on tumors, it is held that the ability of the target antigen to internalize is important for payload release and subsequent tumor cell-killing [24]. However, reports of non-internalizing ADCs still able to exhibit potent anti-tumor activity suggest antigen internalization may not be completely essential to ADC cytotoxicity [25, 26]. Depending on the linker-drug combination, ADCs have been proposed to release payload in response to components of the tumor microenvironment including excess active proteases or reducing equivalents, tumor-associated macrophages, or other mechanisms, though this needs to be further explored [27].

Importantly, many GPCRs fulfill the characteristics for suitable ADC targets. Extracellular membrane and tumor-specific expression signatures provide target epitopes with potential for minimal to no off-target toxicity. Public RNA-seq datasets (e.g. TCGA and CCLE) have been useful for identifying GPCRs highly expressed in tumors and cancer cell lines, including CCR7 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and GPRC5A in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, among others [13]. Still, GPCR-targeted ADCs need to be evaluated in non-cross-reactive species for off-target toxicities such as linker-payload instability, nonspecific binding, and/or uptake into normal cells [28]. Non-targeting isotype control ADCs with equivalent linker-payloads can also be tested. Normal tissue and cell type expression is another critical consideration when identifying ideal GPCR targets, as recognition of the target on non-tumor cells can lead to on-target, off-tumor activity. Thus, ADC safety assessment in cross-reactive species is essential prior to clinical trials. Additionally, the ability of GPCRs to undergo constitutive or agonist-induced internalization has been relatively well-studied [29-31]. As mAb binding has also been shown to promote GPCR internalization [32], this attribute is beneficial for fostering ADC uptake and activity. Years of ongoing research on GPCR functions, assay development, and therapeutic targeting means there is already a wealth of information to provide the basis for rational ADC design for targeting GPCRs. The boom of antibody-based therapeutics in tandem with the extensive characterization of GPCRs justify GPCRs as a suitable antigen choice for ADC development.

4. Anti-GPCR ADCs in Preclinical Development

From our review of the literature, there are currently 7 described GPCR targets of ADCs in clinical and pre-clinical stages. These GPCR targets and their ADCs are detailed in the subsequent sections and are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of GPCR-targeted ADCs

| Target: Name |

GPCR Class | Indication | Payload | Linker | Average DAR |

Developer | Stage | Most recent publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CXCR4 | Class A | CXCR4+ metastatic cancers; osteosarcoma lung met | MMAF | Non-cleavable PEG oxime linker | 2 | The Scripps Research Institute/Calibr | Pre-clinical | 2014 |

| CXCR4 | Class A | Hematopoietic cancers | Aur0131 | AmPEG6C2 | 4 | Pfizer | Pre-clinical | 2019 |

| MMAE | VC | 3.5 | ||||||

| LGR5 | Class A | GI cancer | Genentech | Pre-clinical | 2015 | |||

| PNU159682 | NMS818 | 2 | ||||||

| LGR5 | Class A | GI cancer | MMAE | MC-VC-PAB | 4 | UT Health IMM | Pre-clinical | 2016 |

| LGR5 | Class A | GI cancer | MMAE; DMSA | NH2-PEG4-VC-PAB | 2 | UT Health IMM | Pre-clinical | 2021 |

| FZD7: Septuximab vedotin | Frizzled | Ovarian cancer | MMAE | MC-VC-PABC | 4 | UCSD | Pre-clinical | 2022 |

| CTR | Class B | GBM | MMAE | OSu-Glu-VC-PAB | 7 | University of Melbourne | Pre-clinical | 2017 |

| GPR56 | Adhesion | CRC | DMSA | MC-VC-PAB-DMEA | 3.54 | UT Health IMM | Pre-clinical | 2023 |

| CCR7: JBH 492 | Class A | CLL and NHL | DM4 | Undisclosed | Undisclosed | Novartis | Phase I | 2022 |

| GPR20: DS-6157a | Class A | GIST | DXd | GGFG tetrapeptide | 8 | Daiichi Sankyo | Phase I, Discontinued “no clear response” | 2022 |

4.1. CXCR4

The C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) is a class A GPCR. Binding of its canonical ligand CXCL12 activates G protein subunits that promote Ca2+ intracellular store release and signaling through PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways to mediate chemotaxis, transcription, and cell survival [33]. CXCR4 has many important, well-documented functions in cell migration, proliferation, hematopoiesis, and tissue regeneration [33] and is an attractive target for therapy given its overexpression in many hematological cancers and solid tumor types [34]. Though different groups have reported on the development of CXCR4-targeting ADCs, CXCR4 expression on hematopoietic cells and other normal tissues continues to pose a challenge for targeting this antigen [33].

The first-documented CXCR4-targeted ADC was reported in 2014 by the Scripps Research Institute in collaboration with the California Institute for Biomedical Research (Calibr) [35]. As CXCR4 has been shown to be elevated in different tumor types and metastatic cells [36], it was reasoned that a CXCR4-targeted ADC may have efficacy in patients with CXCR4+ metastatic tumors. A high affinity anti-CXCR4 ADC was generated using a non-cleavable hydrophilic linker via site-specific conjugation to the unnatural amino acid p-acetylphenylalanine. Monomethyl auristatin F (MMAF) was selected as the payload (DAR=2) due to its minimal cell permeability and likely reduced off-target cytotoxicity to nonreplicating hematopoietic stem cells. Lung-metastatic variants of a human osteosarcoma line expressing high levels of CXCR4 (SJSA-1-met), were used to assess in vitro efficacy. SJSA-1-met cell viability was significantly reduced following ADC treatment (IC50 = 0.08 nM) whereas treatment with unconjugated CXCR4 mAb or ADC in CXCR4− cells showed no significant effect. In vivo efficacy of anti-CXCR4 ADC was evaluated in a luciferase-expressing SJSA-1-met xenograft model of lung metastasis. Treatment with CXCR4 mAb or ADC (2.5 mg/kg every 5 days for 3 doses) was initiated once lung tumors were detected using noninvasive bioluminescence imaging. ADC treatment resulted in nearly undetectable tumors by day 8, whereas CXCR4 mAb-treated tumors were comparable to the vehicle cohort. Minimal tolerability studies showed ADC treatment resulted in a 24% decrease in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) populations, suggesting potential adverse effects (Table 2). No follow-up efficacy or safety studies on this ADC were reported.

Table 2.

Reported GPCR-targeted ADC Safety Studies

| Target: Name |

Species Tested |

Results |

|---|---|---|

| CXCR4 | Mouse (Balb/c) (Balb/c wt & CXCR4 knock-in) |

MMAF ADC: No observed change in body weight at 2.5 mg/kg Moderate decrease in CXCR4+ hematopoietic stem cells Aur0131 ADCs: Minimal off-target toxicity, tolerated at 4.5 mg/kg Non-tolerated 10 mg/kg dose induced thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and erythropenia (on-target) |

| LGR5 | Rat (Sprague-Dawley) Mouse (Nu/Nu) (C57BL/6) |

MMAE ADC: Minimal toxicity at 10mg/kg (on-target) PNU159682 ADC: Weight loss, morbidity, liver and gut toxicity, disrupted intestinal villi/crypts at 10 mg/kg (on-target) MMAE ADC: No change in body weight or gut toxicity at 8 mg/kg (off-target) MMAE PDC: No change in body weight or gut toxicity at 15 mg/kg (on-target) |

| FZD7: Septuximab vedotin | Mouse (C57BL/6 wt & Fzd7hF7/hF7) | Minimal toxicity based on body weight and histopathology at 10 mg/kg (off-target/on-target) |

| CTR | N/A | Not reported |

| GPR56 | Mouse (C57BL/6) | Minimal toxicity based on weight, blood chemistry, and hematology at 16 mg/kg (off-target) |

| CCR7: JBH 492 | Monkey (cynomolgous) | Favorable safety profile with no changes in immune cell populations (details not disclosed) |

| GPR20: DS-6157a | Rat (Sprague-Dawley) Monkey (cynomolgous) Human |

Minimal to mild toxicity in rats up to 199 mg/kg (off-target) and monkeys up to 30 mg/kg (on-target) based on weight, blood chemistry, hematology, and histopathology Mild to severe adverse events in GIST patients including nausea, decreased appetite, fatigue, anemia, constipation, decreased platelets, vomiting, abnormal hepatic function, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and one treatment-related death (hepatic failure). |

The most recently described anti-CXCR4 ADCs were generated in 2019 by Pfizer [37]. To identify a lead candidate, the group screened ADC configurations differing in linkers, payloads, DAR, mAb affinities, and Fc format with the goal of empirically improving the TI and reducing off-target toxicity associated with previous CXCR4-targeted therapies. An auristatin (Aur0131) payload was selected due to its cytotoxic effects on tumor cells and lack of toxicity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Candidate ADCs were tested in Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), ALL, MM, and AML cancer cell xenografts (single 3 mg/kg dose). Based on efficacy data, the lead ADC was comprised of a lower affinity mAb with reduced Fc-mediated effector function conjugated via lysine residues to a non-cleavable linker-payload (AmPEG6C2-Aur0131; DAR=4). Treatment in standard-of-care- and CXCR4 mAb-resistant MOLP-8 MM cell xenografts showed a single minimal efficacious dose (0.15 mg/kg) resulted in tumor regression and significantly extended survival. Interestingly, anti-CXCR4 ADC (0.5 mg/kg/dose) increased efficacy of gemcitabine chemotherapy in a CXCR4+ patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) when treated in combination, though ADC monotherapy had negligible effect on tumor growth. Tolerability was assessed in wildtype and human CXCR4 knock-in mice and is summarized in Table 2. Though further pre-clinical validation of this ADC has not been reported, this study demonstrated an empirical approach to ADC design to substantially improve the TI for GPCRs and other targets with broad normal tissue expression.

4.2. LGR5

Leucine-rich repeat-containing, G protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR5) belongs to the Class A family of GPCRs and binds R-spondin (RSPO1-4) growth factor ligands [38]. Unlike traditional GPCRs, LGR5 has not been verified to couple to heterotrimeric G proteins [39]. RSPO-LGR5 potentiates canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling through association with FZD and LRP5/6 co-receptors and mediates cell-cell adhesion through IQ motif containing GTPase activating protein 1 (IQGAP1) [39-41]. LGR5 is a marker of adult stem cells in many epithelial tissues including intestine and stomach [42, 43]. Importantly, LGR5 is highly expressed in many gastrointestinal (GI) cancers with relatively low expression on normal tissue and marks tumor-initiating cancer stem cells (CSCs), making it a favorable therapeutic target [44-49].

Researchers at the Institute of Molecular Medicine (IMM) at UTHealth Houston developed LGR5-targeted ADCs for the treatment of GI cancer composed of a rat-human chimeric LGR5 mAb conjugated to monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) [45]. The efficacy of two anti-LGR5 ADCs with differing linkers conjugated to the same payload were compared (cathepsin B protease-cleavable maleimidocaproyl-valine-citrulline-p-aminobenzoyloxycarbonyl (MC-VC-PAB) linker and a non-cleavable maleimidopropionyl (MP) linker). Both ADCs were conjugated to interchain cysteine residues (DAR=4) and shown to specifically bind LGR5 with high affinity, internalize, and traffic to lysosomes, comparable to the parent mAb. Evaluation of ADCs in LGR5-high LoVo (colorectal) and AGS (gastric) cancer cells showed the ADC with the cleavable linker exhibited 11-fold greater potency than the ADC with non-cleavable linker (IC50 = 2-4.5 nM vs. 47-51 nM, respectively) and was thus selected as the lead for in vivo studies. The anti-LGR5 ADC had no effect in LGR5− cancer cell lines, demonstrating target specificity. In LoVo colorectal cancer (CRC) xenografts, ADC treatment (8 mg/kg weekly, 3 doses) resulted in tumor elimination and no observed off-target toxicity (Table 2). When animals were monitored for recurrence, a subgroup showed tumor regrowth. Interestingly, recurrent tumors were LGR5−, suggesting LGR5+ cancer cells can transition to an LGR5− state to evade ADC treatment and different therapeutic strategies need be employed to target this plasticity.

Though further development of this ADC has not yet been reported, a peptibody drug-conjugate (PDC) targeting LGR5 and its associated receptors LGR4 and LGR6 was described by the same group in 2021 [50]. The peptibody comprised the furin domain of RSPO4, which binds LGR4-6 without potentiating Wnt signaling, fused to an antibody Fc region. PDCs were generated using a site-specific microbial transglutaminase-based conjugation of cleavable (VC) linkers incorporating either MMAE or Duocarmycin SA (DMSA) payloads. In LGR4/5-high LoVo cells, both PDCs were ~3-fold more potent than the anti-LGR5-MMAE ADC. PDC treatment in LoVo xenografts resulted in significant tumor regression and extended survival. Immunocompetent mice had no observable gut toxicities at high dose PDC (Table 2). Since many LGR5− GI cancer cells express LGR4, LGR6, or both based on TCGA RNA-Seq data [50, 51], it stands to reason that the PDCs may have greater efficacy than LGR5-specific ADCs as they target an increased receptor density. Of note, another group recently described RSPO1-based PDCs for the treatment of ovarian cancer [52]. Further development and validation of in vivo efficacy and tolerability have yet to be reported.

Genentech reported on the generation of two anti-LGR5 ADCs comprised of a humanized LGR5 mAb conjugated to different linker-payloads: protease-cleavable MC-VC-PAB-MMAE linked via interchain cysteines (similar to the aforementioned ADC; DAR=3.5) and acid-hydrolysable NMS818 conjugated via engineered cysteines on the heavy chain (DAR=2) [46]. NMS818 contains an acetal component connected to the C-14 hydroxyl of PNU159682, an anthracycline agent that intercalates into DNA, inhibiting topoisomerase II. Though in vitro efficacy was not shown, free MMAE and PNU159682 were tested on quiescent and actively dividing normal keratinocytes and SKBR3 breast cancer cells. MMAE showed high potency in dividing cells, whereas PNU15982 exhibited higher potency and demonstrated cell-killing effects in non-dividing cells at subnanomolar concentrations. This suggested anti-LGR5-NMS818 may have a broader range for cell-killing albeit with potentially increased normal tissue toxicity. ADCs showed similar potency in LGR5-high D5124 primary human pancreatic and LoVo xenograft models, resulting in either tumor stasis or regression (single ~10 mg/kg dose). Neither unconjugated LGR5 mAb nor isotype control mAb had a significant effect on tumor growth. Isotype control ADCs resulted in moderate tumor regression, though much less potent compared to LGR5-targeted ADCs. Anti-LGR5-NMS818 showed severe gut and liver toxicities that were absent in anti-LGR5-MMAE treated mice, indicating linker-payload selection is critical for ADC tolerability (Table 2). Anti-LGR5-MMAE was further evaluated in the APCmin/+; KRASLSL-G12D/+;Villin-Cre genetically engineered mouse model of intestinal tumorigenesis, which more closely reflects CSC biology and tumor heterogeneity. Long-term treatment (5 mg/kg, weekly) resulted in a significant increase in survival and decrease in tumor size. However, total number of tumors was unchanged compared to the control cohort. Of note, as MMAE has been shown to be relatively ineffective against GI tumors [53], it would be of interest to test other linker-payload combinations. Taken together, with the other groups’ studies, these findings support the therapeutic potential of LGR5-targeted therapies to treat different types of cancer.

4.3. FZD7

FZD7 is a Frizzled family GPCR that binds Wnts to mediate canonical β-catenin and non-canonical c-Jun kinase-dependent Wnt signaling. FZD7 expression is upregulated in the mesenchymal and proliferative subtypes of ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma [54]. Importantly, FZD7 correlates with worse median patient survival and has higher expression in ovarian tumors compared to normal tissue [54], suggesting it may be an attractive target for ADC development.

Researchers at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) reported the development of an anti-FZD7 ADC: septuximab vedotin. Septuximab vedotin is composed of a chimeric human-mouse FZD7 mAb conjugated to MMAE via the cleavable VC linker (DAR=4). In vitro experiments in FZD7-positive and knockout (KO) cell lines confirmed lysosomal colocalization of septuximab vedotin. ADC showed increased potency in FZD7+ (MA-148 and PA-1; IC50= 5nM) compared to FZD7− (OVCAR3 and MA-148 FZD7-KO; IC50= 25-60nM) ovarian cancer cell lines. In vivo efficacy was tested using luciferase-expressing MA-148, PA-1, and MA-148 FZD7-KO xenograft models. Significant tumor regression was observed for MA-148 and PA-1 tumors (3mg/kg, twice weekly for 8 doses). No significant tumor growth inhibition (TGI) was observed in MA-148 FZD7-KOs. As septuximab vedotin is specific for binding human FZD7, mice were engineered using CRISPR-Cas9 to convert the mAb epitope on Fzd7 from the mouse to human sequence (Fzd7hF7/hF7), allowing for safety studies to be performed. No overt toxicity or damage to crypt/villi structures in the small intestine where Fzd7 is reportedly expressed in Lgr5+ stem cells was observed (Table 2). Importantly, this ADC avoids off-target effects typically associated with global Wnt inhibition such as impaired tissue homeostasis and regeneration [55]. These initial results rationalize further testing of this ADC in PDX and immunocompetent models to assess its clinical potential.

4.4. CTR

Calcitonin receptor (CTR) is a class B GPCR that responds to calcitonin (CT) peptide hormone and is broadly expressed in adult tissues, most notably in bone where it is highly expressed on osteoclasts [56]. CTR activates PLC, cAMP/PKA, and MAPK signaling [57, 58]. Importantly, CTR is expressed in 76-86% of glioblastoma (GBM) patient biopsies in both malignant glioma cells and glioma stem cells with minimal expression in cerebellum and cortex, suggesting it may represent an attractive ADC target for GBM which has a mean survival time of <15 months [59].

Researchers at the University of Melbourne and Monash reported the development of an anti-CTR ADC comprised of mAb2C4 conjugated to cleavable linker-payload OSu-Glu-VC-PAB-MMAE via lysine terminal ε-amino groups (DAR=7) [60]. ADCs were also generated with ribosome-inactivating protein (RIP) immunotoxins (dianthin and gelonin) but were ineffective as monotherapies. Anti-CTR-MMAE ADC was evaluated using CTR+ high-grade glioma SB2b and JK2 cells and U87MG GBM cells. Experiments were conducted in the presence or absence of SO1861, a triterpene glycoside that promotes lysosomal escape, to enhance ADC efficacy. SO1861 increased anti-CTR-MMAE ADC potency 10-fold (IC50 = 25.1 vs. 2.5 nM). The authors suggest ongoing studies examining toxicity of ADCs in combination with SO1861 in mouse models. Neither in vivo studies nor future development of the anti-CTR ADCs have been reported.

4.5. GPR56

GPR56 is a member of the adhesion GPCR family with important functions in brain development, immune regulation, HSC generation, and tumorigenesis [61]. GPR56 has been shown to couple to Gα12/13 to activate RhoA and mediate Src-Fak adhesion signaling [62, 63]. Importantly, GPR56 is highly expressed in several tumor types including colorectal, breast, liver, pancreas, lung, and ovarian cancers [64-67]. Loss of GRP56 was shown to suppress colorectal tumor growth and sensitize cancer cells to standard chemotherapies[67]. The potential role of GPR56 in tumorigenesis and high expression levels in various tumor types provides rationale that a GPR56-targeted ADC may have significant potential for the treatment of GPR56-high tumors.

The IMM at UTHealth Houston reported the development of 10C7 mAb that binds with high affinity to the extracellular domain of GPR56 and potentiates downstream Src-Fak signaling [62]. An ADC derived from 10C7 was generated for the treatment of CRC, specifically the microsatellite stable subtype (MSS) in which GPR56 is highly expressed and correlates with poor prognosis and survival [68]. To identify an optimal ADC payload, a panel of cytotoxins was screened for potency in CRC cells. 10C7 was conjugated with a cleavable VC linker and the DNA alkylating agent DMSA via interchain cysteine residues (DAR=3.54). When 10C7 ADC was tested in CRC cell lines with different levels of GPR56 expression, potent cytotoxicity was observed in GPR56-high CRC cells (SW620, SW403, and HT-29; IC50 = 3.7-29.4nM) with no effect in GPR56− CRC cells. No significant activity was induced by unconjugated 10C7 or non-targeting control ADC, suggesting a GPR56-dependent mechanism of cancer cell-killing. 10C7 ADC was also tested in GPR56+ patient-derived tumor organoid (PDO) models of metastatic rectal cancer and showed near complete tumor cell-killing by 10C7 ADC compared to moderate reduction in viability from non-targeting ADC. 10C7 ADC showed significant antitumor efficacy in MSS CRC cell xenografts and PDX models (2.5-5 mg/kg/dose, once a week for 3-4 doses). Preliminary safety studies in immunocompetent mice did not show any obvious signs of payload-induced toxicity (Table 2), though target-mediated toxicity may be underestimated due to sequence difference in the 10C7 binding epitope between mouse and human. Comprehensive tolerability studies and efficacy studies in genetic mouse models of CRC have yet to be reported.

5. Anti-GPCR ADCs in Clinical Development

5.1. CCR7

The CC-chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7) is a class A GPCR with two endogenous ligands: CCL19 and CCL21. Functionally, CCR7 has roles in cancer cell migration, metastasis, and immune cell recruitment [69]. Therapeutic targeting of the CCR7 signaling axis remains largely unexplored due to its apparent anti- and pro-tumorigenic effects [70]. Additionally, CCR7 is expressed on several immune cell subtypes including dendritic cells, T central memory cells, naïve T lymphocytes, T regulatory cells, naïve B lymphocytes, and thymocytes [71]. However, CCR7 is highly expressed in many cancer types and correlates with worse prognosis [72-75], making it an attractive therapeutic target.

Novartis reported the development of a CCR7-targeted ADC, JBH492, for the treatment of CLL and NHL [76]. JBH492 consists of an IgG1 antibody conjugated to ravtansine (DM4), a maytansinoid, via a cleavable linker. In vitro studies showed JBH492 has preferential binding for CCR7-high tumor cells versus normal immune cells and functions via DM4-mediated cytotoxicity and inhibition of ligand-induced CCR7 signaling. In vivo studies conducted in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma PDX models achieved partial or complete responses in mice with no notable toxicity or changes in circulating immune cell populations in non-human primates (Table 2). JBH492 monotherapy is currently being investigated in a Phase I/Ib safety and preliminary efficacy study for patients with relapsed/refractory CLL and NHL (NCT04240704).

5.2. GPR20

GPR20 is a class A orphan GPCR overexpressed in GI stromal tumors (GISTs) [77] that constitutively activates Gαi proteins to control cellular cAMP levels [78]. However, its ligand and function in GIST remains elusive. Most adult GISTs are driven by activating mutations in proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase (KIT) or platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA). Notably, the only approved therapies for GISTs are tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). However, tumors often develop secondary resistance mutations in KIT [79], indicating the need for more effective treatment options.

Daiichi Sankyo developed the DS-6157a ADC, a GPR20 mAb conjugated with deruxtecan (DXd) via a highly stable cathepsin-cleavable Gly-Gly-Phe-Gly (GGFG) tetrapeptide linker (DAR=8) [80]. DS-6157a cytotoxicity was evaluated in GIST-T1 cells overexpressing recombinant GPR20 (GIST-T1/GPR20) and GPR20− NCI-N87 gastric cancer cells. DS-6157a only showed activity in GIST-T1/GPR20 cells (IC50=156 ng/mL), demonstrating specificity for GPR20. Enhanced ADCC by DS-6157a was shown by specific PBMC-mediated lysis of GIST-T1/GPR20 cells. DS-6157a antitumor efficacy was assessed in GIST-T1 xenografts and PDX models. Significant TGI was observed in both models treated with DS-6157a (3-10 mg/kg/dose, once every 3 weeks for 1-3 doses). Notably, in GIST-T1 xenografts (10mg/kg/dose for 2 doses), tumor regression persisted for 8 weeks after treatment termination. Neither unconjugated GPR20 mAb nor isotype control ADC impacted tumor growth, indicating TGI was GPR20- and DXd-dependent. Importantly, DS-6157a blocked PDX tumor growth regardless of KIT mutation status whereas efficacy of TKI treatment was variable due to acquired or intrinsic resistance. The pharmacokinetic profile of DS-6157a was determined in cynomolgus monkeys and safety studies were performed in rats and cynomolgus monkeys (Table 2). DS-6157a plasma exposure increased in a dose-dependent manner comparable to total mAb, indicating linker stability in circulation. Safety studies showed minimal or mild toxicities and highest non-severely toxic dose in monkeys of 30 mg/kg (human equivalent dose = 9.6 mg/kg). These findings supported entry of DS-6157a into clinical trials (starting dose = 1.6 mg/kg).

Phase I clinical trials to assess the safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of DS-6157a monotherapy began in May 2020 (NCT04276415). Recruited GIST patients included those that had progressed on or were intolerant to TKI imatinib and had at least one post-imatinib treatment as well as those who were ineligible for imatinib/post-imatinib treatment or curative intent surgical treatment. Unfortunately, nearly all patients experienced mild to severe treatment-emergent and -related adverse events (Table 2). The trial was halted by Daiichi Sankyo due to modest clinical efficacy with a majority of patients experiencing stable or progressive disease as best response [81].

6. Conclusion

Clearly, there is significant diversity in the structure, function, and disease indication associated with GPCRs currently targeted by ADCs. However, these represent only a small fraction of druggable GPCRs, several of which have now been described as biomarkers for a range of cancer types and may represent suitable ADC targets [13]. As such, it is sensible to reason that the number of GPCR-targeted ADCs will continue to expand in the coming years. The future of GPCR-targeted ADCs will be aided by ongoing innovative developments in ADC technology including the generation of bsAb and nanobody formats, novel and dual payloads, and improved linker design [17, 82-87]. Recent clinical trials have focused on combination treatment of ADCs with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and other small molecule agents, such as TKIs [88-91]. Interestingly, GPCR-targeted drug conjugates that directly incorporate alternative payloads such as radionuclides, TKIs, and bromodomain and extraterminal protein inhibitors (BETi), among others, are increasing in prevalence [92-94]. A FZD10 mAb radiolabeled with Yttrium-90, tabituximab barzuxetan, is in ongoing Phase I clinical trials for radiosensitizer treatment of relapsed or refractory synovial sarcoma (NCT04176016) [95, 96]. Preclinical development of a CXCR4-targeted ADC with TKI dasatinib for the treatment of T-cell-mediated immune disorders [6] as well as an LGR5-targeted ADC with BETi RVX208 for the treatment of CRC [97] have been reported. ADCs are one of the fastest growing classes of cancer therapy, having demonstrated promising antitumor efficacy with FDA-approvals obtained for multiple solid tumor and hematological malignancies. As extensive efforts are currently underway in both the biopharma industry and academia to improve cancer therapeutics, the GPCR superfamily represents a hot target for the development of next-generation ADCs.

Highlights.

ADCs are the fastest growing class of anticancer drugs with 12 obtaining FDA-approval, 8 in just the past 5 years.

ADCs are highly specific antibodies linked to cytotoxic payloads designed to destroy tumors while sparing normal cells.

GPCRs are one of the most successful therapeutic targets, accounting for nearly 35% of approved drugs.

GPCRs are emerging targets for the development of ADCs.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NCI, R01CA226894 and R21CA270716), the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (RP210092), and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center UTHealth Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences (GSBS). Schematic illustrations created with BioRender.com.

Abbreviations

- ADC

antibody-drug conjugate

- ADCC

antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

- ALL

acute lymphocytic leukemia

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- BETi

bromodomain and extraterminal protein inhibitor

- bsAb

bispecific antibody

- Cailbr

California Institute for Biomedical Research

- CCLE

Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia

- CCR7

CC-chemokine receptor 7

- CGRP

calcitonin gene-related peptide

- CLL

chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- CSC

cancer stem cell

- CT

calcitonin

- CTR

calcitonin receptor

- CXCR4

C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4

- DAR

drug-to-antibody ratio

- DM4

ravtansine

- DMSA

Duocarmycin SA

- DXd

deruxtecan

- FZD7

Frizzled 7

- FZD10

Frizzled 10

- GBM

glioblastoma

- GGFG

Gly-Gly-Phe-Gly

- GI

gastrointestinal

- GIST

gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- GPR56

G protein-coupled receptor 56

- GPR5CA

G protein-coupled receptor class C group 5 member A

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cell

- IMM

Institute of Molecular Medicine

- IQGAP1

IQ motif containing GTPase activating protein 1

- KIT

proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase

- LGR5

leucine-rich repeat-containing, G protein-coupled receptor 5

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MC-VC-PAB

maleimidocaproyl-valine-citrulline-p-aminobenzoyloxycarbonyl

- MM

multiple myeloma

- MMAE

monomethyl auristatin E

- MMAF

monomethyl auristatin F

- MP

maleimidopropionyl

- MSS

microsatellite stable subtype

- NHL

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- PBMC

peripheral mononuclear cells

- PDGFRA

platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha

- PDC

peptibody drug-conjugate

- PDO

patient-derived tumor organoid

- PDX

patient-derived xenograft

- RIP

ribosome-inactivating protein

- RSPO

R-spondin

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TGI

tumor growth inhibition

- TKI

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- TI

therapeutic index

- UCSD

University of California at San Diego

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interests

There are also no competing financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- [1].Sriram K, Insel PA, G Protein-Coupled Receptors as Targets for Approved Drugs: How Many Targets and How Many Drugs?, Molecular Pharmacology, 93 (2018) 251–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jazayeri A, Dias JM, Marshall FH, From G Protein-coupled Receptor Structure Resolution to Rational Drug Design, J Biol Chem, 290 (2015) 19489–19495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yang D, Zhou Q, Labroska V, Qin S, Darbalaei S, Wu Y, Yuliantie E, Xie L, Tao H, Cheng J, Liu Q, Zhao S, Shui W, Jiang Y, Wang M-W, G protein-coupled receptors: structure- and function-based drug discovery, Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 6 (2021) 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lu R-M, Hwang Y-C, Liu IJ, Lee C-C, Tsai H-Z, Li H-J, Wu H-C, Development of therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of diseases, Journal of Biomedical Science, 27 (2020) 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fu Z, Li S, Han S, Shi C, Zhang Y, Antibody drug conjugate: the “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy, Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 7 (2022) 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wang RE, Liu T, Wang Y, Cao Y, Du J, Luo X, Deshmukh V, Kim CH, Lawson BR, Tremblay MS, Young TS, Kazane SA, Wang F, Schultz PG, An Immunosuppressive Antibody–Drug Conjugate, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 137 (2015) 3229–3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lovey A, Krel M, Borchardt A, Brady T, Cole JN, Do QQ, Fortier J, Hough G, Jiang W, Noncovich A, Tari L, Zhao Q, Balkovec JM, Zhao Y, Perlin DS, Development of Novel Immunoprophylactic Agents against Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections, Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 65 (2021) e0098521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gustafsson K, Rhee CS, Scadden EW, Frodermann V, Palchaudhuri R, Hyzy SL, Proctor JL, Gillard GO, Boitano AE, Cooke MP, Nahrendorf M, Scadden DT, Reversing Clonal Hematopoiesis and Associated Atherosclerotic Disease By Targeted Antibody-Drug-Conjugate (ADC) Conditioning and Transplant, Blood, 136 (2020) 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rosenbaum DM, Rasmussen SG, Kobilka BK, The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors, Nature, 459 (2009) 356–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fredriksson R, Lagerström MC, Lundin LG, Schiöth HB, The G-protein-coupled receptors in the human genome form five main families. Phylogenetic analysis, paralogon groups, and fingerprints, Mol Pharmacol, 63 (2003) 1256–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Congreve M, de Graaf C, Swain NA, Tate CG, Impact of GPCR Structures on Drug Discovery, Cell, 181 (2020) 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hauser AS, Attwood MM, Rask-Andersen M, Schiöth HB, Gloriam DE, Trends in GPCR drug discovery: new agents, targets and indications, Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 16 (2017) 829–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Insel PA, Sriram K, Wiley SZ, Wilderman A, Katakia T, McCann T, Yokouchi H, Zhang L, Corriden R, Liu D, Feigin ME, French RP, Lowy AM, Murray F, GPCRomics: GPCR Expression in Cancer Cells and Tumors Identifies New, Potential Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets, Front Pharmacol, 9 (2018) 431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].O'Hayre M, Vázquez-Prado J, Kufareva I, Stawiski EW, Handel TM, Seshagiri S, Gutkind JS, The emerging mutational landscape of G proteins and G-protein-coupled receptors in cancer, Nat Rev Cancer, 13 (2013) 412–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hutchings CJ, A review of antibody-based therapeutics targeting G protein-coupled receptors: an update, Expert Opin Biol Ther, 20 (2020) 925–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Douthwaite JA, Finch DK, Mustelin T, Wilkinson TCI, Development of therapeutic antibodies to G protein-coupled receptors and ion channels: Opportunities, challenges and their therapeutic potential in respiratory diseases, Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 169 (2017) 113–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Su Z, Xiao D, Xie F, Liu L, Wang Y, Fan S, Zhou X, Li S, Antibody–drug conjugates: Recent advances in linker chemistry, Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B, 11 (2021) 3889–3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Baah S, Laws M, Rahman KM, Antibody–Drug Conjugates—A Tutorial Review, Molecules, 26 (2021) 2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chari RV, Miller ML, Widdison WC, Antibody-drug conjugates: an emerging concept in cancer therapy, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 53 (2014) 3796–3827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kang MS, Kong TWS, Khoo JYX, Loh T-P, Recent developments in chemical conjugation strategies targeting native amino acids in proteins and their applications in antibody-drug conjugates, Chem Sci, 12 (2021) 13613–13647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Walsh SJ, Bargh JD, Dannheim FM, Hanby AR, Seki H, Counsell AJ, Ou X, Fowler E, Ashman N, Takada Y, Isidro-Llobet A, Parker JS, Carroll JS, Spring DR, Site-selective modification strategies in antibody–drug conjugates, Chemical Society Reviews, 50 (2021) 1305–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ritchie M, Tchistiakova L, Scott N, Implications of receptor-mediated endocytosis and intracellular trafficking dynamics in the development of antibody drug conjugates, MAbs, 5 (2013) 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Criscitiello C, Morganti S, Curigliano G, Antibody–drug conjugates in solid tumors: a look into novel targets, Journal of Hematology & Oncology, 14 (2021) 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Donaghy H, Effects of antibody, drug and linker on the preclinical and clinical toxicities of antibody-drug conjugates, MAbs, Taylor & Francis, 2016, pp. 659–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gébleux R, Stringhini M, Casanova R, Soltermann A, Neri D, Non-internalizing antibody-drug conjugates display potent anti-cancer activity upon proteolytic release of monomethyl auristatin E in the subendothelial extracellular matrix, Int J Cancer, 140 (2017) 1670–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dal Corso A, Gébleux R, Murer P, Soltermann A, Neri D, A non-internalizing antibody-drug conjugate based on an anthracycline payload displays potent therapeutic activity in vivo, J Control Release, 264 (2017) 211–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Staudacher AH, Brown MP, Antibody drug conjugates and bystander killing: is antigen-dependent internalisation required?, Br J Cancer, 117 (2017) 1736–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fisher JE Jr., Considerations for the Nonclinical Safety Evaluation of Antibody-Drug Conjugates, Antibodies (Basel), 10 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Foster SR, Bräuner-Osborne H, Investigating Internalization and Intracellular Trafficking of GPCRs: New Techniques and Real-Time Experimental Approaches, Handb Exp Pharmacol, 245 (2018) 41–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ferguson SS, Evolving concepts in G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis: the role in receptor desensitization and signaling, Pharmacol Rev, 53 (2001) 1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Moo EV, van Senten JR, Bräuner-Osborne H, Møller TC, Arrestin-Dependent and -Independent Internalization of G Protein-Coupled Receptors: Methods, Mechanisms, and Implications on Cell Signaling, Mol Pharmacol, 99 (2021) 242–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ullmer C, Zoffmann S, Bohrmann B, Matile H, Lindemann L, Flor P, Malherbe P, Functional monoclonal antibody acts as a biased agonist by inducing internalization of metabotropic glutamate receptor 7, Br J Pharmacol, 167 (2012) 1448–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bianchi ME, Mezzapelle R, The Chemokine Receptor CXCR4 in Cell Proliferation and Tissue Regeneration, Frontiers in Immunology, 11 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Balkwill F, The significance of cancer cell expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR4, Seminars in cancer biology, Elsevier, 2004, pp. 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kularatne SA, Deshmukh V, Ma J, Tardif V, Lim RK, Pugh HM, Sun Y, Manibusan A, Sellers AJ, Barnett RS, Srinagesh S, Forsyth JS, Hassenpflug W, Tian F, Javahishvili T, Felding-Habermann B, Lawson BR, Kazane SA, Schultz PG, A CXCR4-targeted site-specific antibody-drug conjugate, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 53 (2014) 11863–11867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Darash-Yahana M, Pikarsky E, Abramovitch R, Zeira E, Pal B, Karplus R, Beider K, Avniel S, Kasem S, Galun E, Peled A, Role of high expression levels of CXCR4 in tumor growth, vascularization, and metastasis, Faseb j, 18 (2004) 1240–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Costa MJ, Kudaravalli J, Ma J-T, Ho W-H, Delaria K, Holz C, Stauffer A, Chunyk AG, Zong Q, Blasi E, Buetow B, Tran T-T, Lindquist K, Dorywalska M, Rajpal A, Shelton DL, Strop P, Liu S-H, Optimal design, anti-tumour efficacy and tolerability of anti-CXCR4 antibody drug conjugates, Scientific Reports, 9 (2019) 2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Carmon KS, Gong X, Lin Q, Thomas A, Liu Q, R-spondins function as ligands of the orphan receptors LGR4 and LGR5 to regulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108 (2011) 11452–11457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Carmon KS, Gong X, Yi J, Wu L, Thomas A, Moore CM, Masuho I, Timson DJ, Martemyanov KA, Liu QJ, LGR5 receptor promotes cell-cell adhesion in stem cells and colon cancer cells via the IQGAP1-Rac1 pathway, J Biol Chem, 292 (2017) 14989–15001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Carmon KS, Lin Q, Gong X, Thomas A, Liu Q, LGR5 interacts and cointernalizes with Wnt receptors to modulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling, Mol Cell Biol, 32 (2012) 2054–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Park S, Wu L, Tu J, Yu W, Toh Y, Carmon KS, Liu QJ, Unlike LGR4, LGR5 potentiates Wnt-β-catenin signaling without sequestering E3 ligases, Sci Signal, 13 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, Cozijnsen M, Haegebarth A, Korving J, Begthel H, Peters PJ, Clevers H, Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5, Nature, 449 (2007) 1003–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Barker N, Huch M, Kujala P, van de Wetering M, Snippert HJ, van Es JH, Sato T, Stange DE, Begthel H, van den Born M, Danenberg E, van den Brink S, Korving J, Abo A, Peters PJ, Wright N, Poulsom R, Clevers H, Lgr5(+ve) Stem Cells Drive Self-Renewal in the Stomach and Build Long-Lived Gastric Units In Vitro, Cell Stem Cell, 6 (2010) 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hirsch D, Barker N, McNeil N, Hu Y, Camps J, McKinnon K, Clevers H, Ried T, Gaiser T, LGR5 positivity defines stem-like cells in colorectal cancer, Carcinogenesis, 35 (2014) 849–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Gong X, Azhdarinia A, Ghosh SC, Xiong W, An Z, Liu Q, Carmon KS, LGR5-Targeted Antibody-Drug Conjugate Eradicates Gastrointestinal Tumors and Prevents Recurrence, Mol Cancer Ther, 15 (2016) 1580–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Junttila MR, Mao W, Wang X, Wang BE, Pham T, Flygare J, Yu SF, Yee S, Goldenberg D, Fields C, Eastham-Anderson J, Singh M, Vij R, Hongo JA, Firestein R, Schutten M, Flagella K, Polakis P, Polson AG, Targeting LGR5+ cells with an antibody-drug conjugate for the treatment of colon cancer, Sci Transl Med, 7 (2015) 314ra186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].de Sousa e Melo F, Kurtova AV, Harnoss JM, Kljavin N, Hoeck JD, Hung J, Anderson JE, Storm EE, Modrusan Z, Koeppen H, Dijkgraaf GJ, Piskol R, de Sauvage FJ, A distinct role for Lgr5(+) stem cells in primary and metastatic colon cancer, Nature, 543 (2017) 676–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Merlos-Suárez A, Barriga FM, Jung P, Iglesias M, Céspedes MV, Rossell D, Sevillano M, Hernando-Momblona X, da Silva-Diz V, Muñoz P, Clevers H, Sancho E, Mangues R, Batlle E, The intestinal stem cell signature identifies colorectal cancer stem cells and predicts disease relapse, Cell Stem Cell, 8 (2011) 511–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Shimokawa M, Ohta Y, Nishikori S, Matano M, Takano A, Fujii M, Date S, Sugimoto S, Kanai T, Sato T, Visualization and targeting of LGR5+ human colon cancer stem cells, Nature, 545 (2017) 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cui J, Toh Y, Park S, Yu W, Tu J, Wu L, Li L, Jacob J, Pan S, Carmon KS, Liu QJ, Drug Conjugates of Antagonistic R-Spondin 4 Mutant for Simultaneous Targeting of Leucine-Rich Repeat-Containing G Protein-Coupled Receptors 4/5/6 for Cancer Treatment, J Med Chem, 64 (2021) 12572–12581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Yi J, Xiong W, Gong X, Bellister S, Ellis LM, Liu Q, Analysis of LGR4 Receptor Distribution in Human and Mouse Tissues, PLOS ONE, 8 (2013) e78144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wong C, Mulero MC, Barth EI, Wang K, Shang X, Tikle S, Rice C, Gately D, Howell SB, Exploiting the receptor-binding domains of RSPO1 to target LGR5-expressing stem cells in ovarian cancer, Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, (2023) JPET-AR-2022-001495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Tolcher AW, Antibody drug conjugates: lessons from 20 years of clinical experience, Ann Oncol, 27 (2016) 2168–2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Do M, Wu CCN, Sonavane PR, Juarez EF, Adams SR, Ross J, Rodriguez YBA, Patel C, Mesirov JP, Carson DA, Advani SJ, Willert K, A FZD7-specific Antibody-Drug Conjugate Induces Ovarian Tumor Regression in Preclinical Models, Mol Cancer Ther, 21 (2022) 113–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Jung Y-S, Park J-I, Wnt signaling in cancer: therapeutic targeting of Wnt signaling beyond β-catenin and the destruction complex, Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 52 (2020) 183–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ostrovskaya A, Hick C, Hutchinson DS, Stringer BW, Wookey PJ, Wootten D, Sexton PM, Furness SG, Expression and activity of the calcitonin receptor family in a sample of primary human high-grade gliomas, BMC cancer, 19 (2019) 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Pondel M, Calcitonin and calcitonin receptors: bone and beyond, International journal of experimental pathology, 81 (2000) 405–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Chen Y, Shyu J-F, Santhanagopal A, Inoue D, David J-P, Dixon SJ, Horne WC, Baron R, The calcitonin receptor stimulates Shc tyrosine phosphorylation and Erk1/2 activation: involvement of Gi, protein kinase C, and calcium, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 273 (1998) 19809–19816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Gupta P, Furness SGB, Bittencourt L, Hare DL, Wookey PJ, Building the case for the calcitonin receptor as a viable target for the treatment of glioblastoma, Ther Adv Med Oncol, 12 (2020) 1758835920978110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gilabert-Oriol R, Furness SGB, Stringer BW, Weng A, Fuchs H, Day BW, Kourakis A, Boyd AW, Hare DL, Thakur M, Johns TG, Wookey PJ, Dianthin-30 or gelonin versus monomethyl auristatin E, each configured with an anti-calcitonin receptor antibody, are differentially potent in vitro in high-grade glioma cell lines derived from glioblastoma, Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy, 66 (2017) 1217–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Singh AK, Lin HH, The role of GPR56/ADGRG1 in health and disease, Biomed J, 44 (2021) 534–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Chatterjee T, Zhang S, Posey TA, Jacob J, Wu L, Yu W, Francisco LE, Liu QJ, Carmon KS, Anti-GPR56 monoclonal antibody potentiates GPR56-mediated Src-Fak signaling to modulate cell adhesion, J Biol Chem, 296 (2021) 100261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Iguchi T, Sakata K, Yoshizaki K, Tago K, Mizuno N, Itoh H, Orphan G Protein–coupled Receptor GPR56 Regulates Neural Progenitor Cell Migration via a G alpha 12/13 and Rho Pathway, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 283 (2008) 14469–14478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Ke N, Sundaram R, Liu G, Chionis J, Fan W, Rogers C, Awad T, Grifman M, Yu D, Wong-Staal F, Orphan G protein–coupled receptor GPR56 plays a role in cell transformation and tumorigenesis involving the cell adhesion pathway, Molecular cancer therapeutics, 6 (2007) 1840–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Sewda K, Coppola D, Enkemann S, Yue B, Kim J, Lopez AS, Wojtkowiak JW, Stark VE, Morse B, Shibata D, Cell-surface markers for colon adenoma and adenocarcinoma, Oncotarget, 7 (2016) 17773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Liu Z, Huang Z, Yang W, Li Z, Xing S, Li H, Hu B, Li P, Expression of orphan GPR56 correlates with tumor progression in human epithelial ovarian cancer, Neoplasma, 64 (2017) 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Zhang S, Chatterjee T, Godoy C, Wu L, Liu QJ, Carmon KS, GPR56 Drives Colorectal Tumor Growth and Promotes Drug Resistance through Upregulation of MDR1 Expression via a RhoA-Mediated MechanismGPR56 Promotes Drug Resistance, Molecular Cancer Research, 17 (2019) 2196–2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Jacob J, Francisco LE, Chatterjee T, Liang Z, Subramanian S, Liu QJ, Rowe JH, Carmon KS, An antibody–drug conjugate targeting GPR56 demonstrates efficacy in preclinical models of colorectal cancer, British Journal of Cancer, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Legler DF, Uetz-von Allmen E, Hauser MA, CCR7: roles in cancer cell dissemination, migration and metastasis formation, Int J Biochem Cell Biol, 54 (2014) 78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Salem A, Alotaibi M, Mroueh R, Basheer HA, Afarinkia K, CCR7 as a therapeutic target in Cancer, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer, 1875 (2021) 188499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Comerford I, Harata-Lee Y, Bunting MD, Gregor C, Kara EE, McColl SR, A myriad of functions and complex regulation of the CCR7/CCL19/CCL21 chemokine axis in the adaptive immune system, Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews, 24 (2013) 269–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Müller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, McClanahan T, Murphy E, Yuan W, Wagner SN, Barrera JL, Mohar A, Verástegui E, Zlotnik A, Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis, Nature, 410 (2001) 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Schimanski CC, Schwald S, Simiantonaki N, Jayasinghe C, Gönner U, Wilsberg V, Junginger T, Berger MR, Galle PR, Moehler M, Effect of Chemokine Receptors CXCR4 and CCR7 on the Metastatic Behavior of Human Colorectal Cancer, Clinical Cancer Research, 11 (2005) 1743–1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Yang J, Wang S, Zhao G, Sun B, Effect of chemokine receptors CCR7 on disseminated behavior of human T cell lymphoma: clinical and experimental study, J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 30 (2011) 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Goto M, Liu M, Chemokines and their receptors as biomarkers in esophageal cancer, Esophagus, 17 (2020) 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Dang A, Knee D, Wang CY, Gao F, Liu G, Briones S, Coulson M, Makofske J, Mansfield K, Liu M, Mulvey T, Meseck EK, Woolfenden S, Buchanan SG, Steensma D, Askoxylakis V, A Novel Antibody-Drug Conjugate Targeting CCR7 in Hematologic Malignancies, Blood, 140 (2022) 11564–11565. [Google Scholar]

- [77].Allander SV, Nupponen NN, Ringnér M, Hostetter G, Maher GW, Goldberger N, Chen Y, Carpten J, Elkahloun AG, Meltzer PS, Gastrointestinal stromal tumors with KIT mutations exhibit a remarkably homogeneous gene expression profile, Cancer Res, 61 (2001) 8624–8628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Hase M, Yokomizo T, Shimizu T, Nakamura M, Characterization of an Orphan G Protein-coupled Receptor, GPR20, That Constitutively Activates Gi Proteins, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 283 (2008) 12747–12755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Liegl B, Kepten I, Le C, Zhu M, Demetri GD, Heinrich MC, Fletcher CD, Corless CL, Fletcher JA, Heterogeneity of kinase inhibitor resistance mechanisms in GIST, J Pathol, 216 (2008) 64–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Iida K, Abdelhamid Ahmed AH, Nagatsuma AK, Shibutani T, Yasuda S, Kitamura M, Hattori C, Abe M, Hasegawa J, Iguchi T, Karibe T, Nakada T, Inaki K, Kamei R, Abe Y, Nomura T, Andersen JL, Santagata S, Hemming ML, George S, Doi T, Ochiai A, Demetri GD, Agatsuma T, Identification and Therapeutic Targeting of GPR20, Selectively Expressed in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors, with DS-6157a, a First-in-Class Antibody-Drug Conjugate, Cancer Discov, 11 (2021) 1508–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].George S, Heinrich MC, Somaiah N, Tine BAV, McLeod R, Laadem A, Cheng B, Nishioka S, Kundu MG, Qian X, Lau YY, Tran B, Kumar P, Dosunmu O, Shi J, Naito Y, A phase 1, multicenter, open-label, first-in-human study of DS-6157a in patients (pts) with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), Journal of Clinical Oncology, 40 (2022) 11512–11512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Andreev J, Thambi N, Perez Bay AE, Delfino F, Martin J, Kelly MP, Kirshner JR, Rafique A, Kunz A, Nittoli T, Bispecific Antibodies and Antibody–Drug Conjugates (ADCs) Bridging HER2 and Prolactin Receptor Improve Efficacy of HER2 ADCsHER2xPRLR Bispecific ADCs Improve Upon HER2 ADC Efficacy, Molecular cancer therapeutics, 16 (2017) 681–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Deng C, Xiong J, Gu X, Chen X, Wu S, Wang Z, Wang D, Tu J, Xie J, Novel recombinant immunotoxin of EGFR specific nanobody fused with cucurmosin, construction and antitumor efficiency in vitro, Oncotarget, 8 (2017) 38568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Huang H, Wu T, Shi H, Wu Y, Yang H, Zhong K, Wang Y, Liu Y, Modular design of nanobody–drug conjugates for targeted-delivery of platinum anticancer drugs with an MRI contrast agent, Chemical Communications, 55 (2019) 5175–5178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Kang W, Ding C, Zheng D, Ma X, Yi L, Tong X, Wu C, Xue C, Yu Y, Zhou Q, Nanobody Conjugates for Targeted Cancer Therapy and Imaging, Technol Cancer Res Treat, 20 (2021) 15330338211010117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Yamazaki CM, Yamaguchi A, Anami Y, Xiong W, Otani Y, Lee J, Ueno NT, Zhang N, An Z, Tsuchikama K, Antibody-drug conjugates with dual payloads for combating breast tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance, Nature Communications, 12 (2021) 3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Conilh L, Sadilkova L, Viricel W, Dumontet C, Payload diversification: a key step in the development of antibody–drug conjugates, Journal of Hematology & Oncology, 16 (2023) 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Patel TA, Ensor JE, Creamer SL, Boone T, Rodriguez AA, Niravath PA, Darcourt JG, Meisel JL, Li X, Zhao J, A randomized, controlled phase II trial of neoadjuvant ado-trastuzumab emtansine, lapatinib, and nab-paclitaxel versus trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and paclitaxel in HER2-positive breast cancer (TEAL study), Breast Cancer Research, 21 (2019) 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Sellmann C, Doerner A, Knuehl C, Rasche N, Sood V, Krah S, Rhiel L, Messemer A, Wesolowski J, Schuette M, Becker S, Toleikis L, Kolmar H, Hock B, Balancing Selectivity and Efficacy of Bispecific Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) x c-MET Antibodies and Antibody-Drug Conjugates, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 291 (2016) 25106–25119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Abrahams C, Krimm S, Li X, Zhou S, Hanson J, Masikat MR, Bajjuri K, Heibeck T, Kothari D, Yu A, Abstract NT-090: Preclinical activity and safety of stro-002, A novel adc targeting folate receptor alpha for ovarian and endometrial cancer, Clinical Cancer Research, 25 (2019) NT-090–NT-090. [Google Scholar]

- [91].Nicolò E, Giugliano F, Ascione L, Tarantino P, Corti C, Tolaney SM, Cristofanilli M, Curigliano G, Combining antibody-drug conjugates with immunotherapy in solid tumors: current landscape and future perspectives, Cancer Treatment Reviews, 106 (2022) 102395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Sgouros G, Bodei L, McDevitt MR, Nedrow JR, Radiopharmaceutical therapy in cancer: clinical advances and challenges, Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 19 (2020) 589–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Fuentes-Antrás J, Genta S, Vijenthira A, Siu LL, Antibody-drug conjugates: in search of partners of choice, Trends in Cancer, 9 (2023) 339–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Pillow TH, Adhikari P, Blake RA, Chen J, Del Rosario G, Deshmukh G, Figueroa I, Gascoigne KE, Kamath AV, Kaufman S, Kleinheinz T, Kozak KR, Latifi B, Leipold DD, Sing Li C, Li R, Mulvihill MM, O'Donohue A, Rowntree RK, Sadowsky JD, Wai J, Wang X, Wu C, Xu Z, Yao H, Yu SF, Zhang D, Zang R, Zhang H, Zhou H, Zhu X, Dragovich PS, Antibody Conjugation of a Chimeric BET Degrader Enables in vivo Activity, ChemMedChem, 15 (2020) 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Giraudet A-L, Cassier PA, Iwao-Fukukawa C, Garin G, Badel J-N, Kryza D, Chabaud S, Gilles-Afchain L, Clapisson G, Desuzinges C, Sarrut D, Halty A, Italiano A, Mori M, Tsunoda T, Katagiri T, Nakamura Y, Alberti L, Cropet C, Baconnier S, Berge-Montamat S, Pérol D, Blay J-Y, A first-in-human study investigating biodistribution, safety and recommended dose of a new radiolabeled MAb targeting FZD10 in metastatic synovial sarcoma patients, BMC Cancer, 18 (2018) 646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Fukukawa C, Hanaoka H, Nagayama S, Tsunoda T, Toguchida J, Endo K, Nakamura Y, Katagiri T, Radioimmunotherapy of human synovial sarcoma using a monoclonal antibody against FZD10, Cancer Science, 99 (2008) 432–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Orouji E, Raman AT, Singh AK, Sorokin A, Arslan E, Ghosh AK, Schulz J, Terranova C, Jiang S, Tang M, Maitituoheti M, Callahan SC, Barrodia P, Tomczak K, Jiang Y, Jiang Z, Davis JS, Ghosh S, Lee HM, Reyes-Uribe L, Chang K, Liu Y, Chen H, Azhdarinia A, Morris J, Vilar E, Carmon KS, Kopetz SE, Rai K, Chromatin state dynamics confers specific therapeutic strategies in enhancer subtypes of colorectal cancer, Gut, 71 (2022) 938–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]