Abstract

A. butzleri is an underappreciated emerging global pathogen, despite growing evidence that it is a major contributor of diarrheal illness. Few studies have investigated the occurrence and public health risks that this organism possesses from waterborne exposure routes including through stormwater use. In this study, we assessed the prevalence, virulence potential, and primary sources of stormwater-isolated A. butzleri in fecally contaminated urban stormwater systems. Based on qPCR, A. butzleri was the most common enteric bacterial pathogen [25%] found in stormwater among a panel of pathogens surveyed, including Shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli (STEC) [6%], Campylobacter spp. [4%], and Salmonella spp. [<1%]. Concentrations of the bacteria, based on qPCR amplification of the single copy gene hsp60, were as high as 6.2 log10 copies/100 mL, suggesting significant loading of this pathogen in some stormwater systems. Importantly, out of 73 unique stormwater culture isolates, 90% were positive for the putative virulence genes cadF, ciaB, tlyA, cjl349, pldA, and mviN, while 50–75% of isolates also possessed the virulence genes irgA, hecA, and hecB. Occurrence of A. butzleri was most often associated with the human fecal pollution marker HF183 in stormwater samples. These results suggest that A. butzleri may be an important bacterial pathogen in stormwater, warranting further study on the risks it represents to public health during stormwater use.

Keywords: Arcobacter, stormwater, water quality, enteric bacterial pathogens, water pollution, microbial contamination, urban drainage

Short abstract

Pathogenic A. butzleri were frequently detected in urban stormwater, and most often associated with human fecal contamination. The findings raise public health concerns about stormwater as an alternative water source.

1. Introduction

Arcobacter spp. are an emerging threat to public health, and one which is not yet well understood. First characterized as a genus by Vandamme et al.,1Arcobacter and the closely related human pathogen Campylobacter both belong to the family Campylobacteraceae, though Arcobacter has been found to grow at lower temperatures (e.g., ≤ 30 °C), and is aerotolerant.1−4 While more than 29 species of Arcobacter have currently been identified,5 the three most important pathogens within the genus include A. butzleri, A. cryaerophilus, and A. skirrowii, with A. butzleri being responsible for the majority of cases of gastrointestinal illness,5,6 and with some strains even causing bacteremia in severe cases.7

Arcobacter is not commonly targeted in clinical diagnostic samples taken from patients exhibiting symptoms of gastrointestinal illness,6,8 despite that some studies have identified A. butzleri as the fourth most common Campylobacter-like species (after C. jejuni, C. coli, and C. lari) isolated from human fecal specimens.6,9−11Arcobacter spp., including specifically A. butzleri, are primarily associated with foodborne illness, and have been found within the feces of several animals, including geese, dogs, chickens, cattle, sheep, pigs, and tissues of shellfish.12−16 In terms of food products, Arcobacter spp. have been detected in milk,17 raw vegetables,18 and meat products,13,14 with the latter being most likely contaminated from infected carcasses during the slaughter and evisceration process.16

Importantly, Arcobacter spp. (particularly A. butzleri and A. cryaerophilus) have been frequently found to be dominant members of the community profiles of sewage treatment plants.19−24 As a genus, Arcobacter has also increasingly been detected in environmental waters, including groundwater,25 lake water,26 river water,27 irrigation water,28,29 stormwater,30−32 and even hurricane floodwaters.33 Their presence in environmental waters have been found to be associated with fecal indicator bacterial contamination26,27,29 as well as the human fecal marker HF183,19,26,31 albeit the bacteria can also survive for long periods of time in water.4 Some studies have even suggested that A. butzleri has the potential to grow and replicate in certain nonhost environments,19−24 and at low temperature.34,35 Importantly, A. butzleri has been implicated in a waterborne disease outbreak25 though this may be underassessed due to a lack of widespread and standardized methods for environmental assessment of this pathogen in water.36

Although some studies have demonstrated that Arcobacter is a major microbial contaminant in stormwater,30−32 little is actually known about the occurrence of specific pathogenic species in stormwater (such as A. butzleri) and their pathogenic potential. As stormwater is increasingly being seen as an untapped alternative source water in many jurisdictions, an understanding of the occurrence and concentrations of pathogenic Arcobacter species, such as A. butzleri, along with their virulence potential, becomes paramount for performing microbial risk assessments associated with stormwater use.

Taking the above into consideration, a multiyear study was conducted on determining the prevalence of the clinically dominant Arcobacter species, known as A. butzleri, in stormwater systems in Alberta, Canada, and to interrogate the virulence potential of isolates collected from stormwater. The intent of this study was to enhance our understanding of A. butzleri occurrence and virulence potential in stormwater, to better inform risk assessments surrounding this emerging pathogen, and as urban cities adapt to using stormwater as an alternative water source.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites and Sample Collection

Stormwater samples were collected from five stormwater ponds (East Lake, Windsong, Hillcrest, King’s Heights North, and King’s Heights South) and two stormwater-impacted creeks (Nose Creek, and the Canals) in Airdrie, Alberta in 2020 and 2021, as well as three stormwater ponds (McCall Lake, Country Hills, and Inverness) in Calgary, Alberta in 2017 (See Tables S1, S2 and Figure S1–S8 in Supporting Information File 1 for coordinates and aerial maps of each pond). Overall, 210 stormwater outfall samples were collected from Airdrie from over 39 sites during two years of sampling (August – September of 2020, and July–September of 2021), while 533 samples were collected from 13 sites in Calgary during 2017 (May – September). Airdrie sites were sampled four to seven times each sampling season (dependent on year and site), while Calgary sites were each sampled forty-one times over the 2017 sampling season. Stormwater sampling from ponds and creeks in Airdrie and Calgary occurred via routine testing of outfalls (weekly or biweekly), wherein 200 mL or 1 L sterile bottles were grab-sampled from outfalls, before shipping overnight on ice to the University of Alberta. All samples were processed within 24 h of sampling.

2.2. Miniaturized MPN Culture Methods

A miniaturized most-probable-number (MPN) assay was used to detect viable A. butzleri in stormwater from McCall Lake sites, being modified from the Campylobacter MPN assay described for irrigation water/wastewater by Banting et al.,28 with a few modifications described below. This assay was designed to be similar to a standard MPN assay, with the exception that qPCR was used as a confirmation method to determine whether individual MPN wells were positive or negative for growth of A. butzleri.

2.2.1. Sample Preparation

In brief, 400 mL of each stormwater sample was first centrifuged at 10,000g in sterile Nalgene bottles using a Sorvall RC-5B Refrigerated Superspeed Centrifuge (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 20 min at 20 °C. Resulting pellets were suspended in 4 mL of Bolton Broth (BB) with BB selective supplements (Thermofisher, Ontario, Canada). Of this 4 mL sample, 3 mL was taken of each sample and was split into three 1 mL aliquots, with each aliquot added to 1 mL wells in a 96-well plate (Greiner BioOne, Monroe, NC), before being serially diluted to 10–7 in BB within the same plate. The 96-well plates were incubated at 30 °C for 48 h in microaerophilic conditions, using Mitsubishi AnaeroPack-MicroAero packs (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Positive controls for this assay consisted of two ongoing precision and recovery (OPR) controls, as well as a matrix spike, all using an environmental strain of A. butzleri and positive for the A. butzleri-specific hsp60 qPCR assay.8 Respectively, the first and second OPR controls used A. butzleri spiked into either PBS and spiked autoclaved stormwater (selected from a random sample during the same sampling date that unknowns were tested), and the matrix spike consisted of A. butzleri spiked into a random fresh stormwater sample from the same sampling date. Negative controls consisted of wells with PBS and sterile media only, as well as a “no-template” control during qPCR. All positive controls were consistently positive, and negative controls were consistently negative for this assay throughout this study.

2.2.2. MPN Determination by qPCR

After incubation, 100 μL of each well from MPN plates was transferred and diluted in sterile water at a 1:10 dilution to further limit possible qPCR inhibition due to any influence of media and before DNA extraction occurred via boiling at 95 °C for 10 min. An internal amplification control (IAC) consisting of a unique artificially designed 198-bp sequence developed by Deer et al.37 that was spiked into each MPN well, with 100 copies added to each well to test for inhibition. Sample wells were deemed inhibited if the cycle threshold (Ct) of the detected IAC in each well varied by ≥3 Cts from the average Ct of the IAC in all other samples including controls. The selection of a 3 Ct cutoff represents a threshold of inhibition congruent with U.S. EPA Method 1611.38 Under these conditions, all MPN qPCR data presented in this manuscript was free of inhibition as determined by the internal amplification control. Individual wells on MPN plates were tested for A. butzleri growth through the A. butzleri-specific hsp60 PCR primers first developed by de Boer et al.8 (see Table S3 [in Supporting Information File 1] for target sequences) and were deemed positive for A. butzleri when: (i) hsp60 was detected, (ii) the Cts were <35, and (iii) inhibition was not observed. qPCR cycling conditions are provided below. Enumeration of qPCR-positive wells were performed using standard three-tube MPN tables, with final volumes reported as MPN/300 mL. Note that all negative controls were negative for amplification, all positive controls were consistently positive, and all samples were negative for inhibition according to the IAC protocol outlined above.

2.3. Culture-based Detection of STEC in Stormwater

For some stormwater samples collected in Calgary (2017) and Airdrie (2020) we assessed STEC occurrence by culture-based methods. Briefly, 100 mL of stormwater samples were incubated with Colilert(R) (IDEXX Laboratories, Inc.; Westbrook, Maine) in presence/absence vessels or Quanti-tray 2000(R) trays at 35 °C for 24 h, as instructed by manufacturer. One mL of E. coli-positive cultures was taken using a pipet for presence/absence vessels, and a syringe was used to extract all liquid out of E. coli positive wells of the Quanti-tray 2000(R). The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 X g for 5 min to pellet bacteria. The supernatant was then removed, and the resulting pellet resuspended in 1 mL of PBS before the centrifugation step was repeated. The supernatant was again removed, and the bacterial pellet resuspended in 100 μL of PBS. DNA from this volume of sample was then extracted by boiling at 95 °C for 10 min and used as a template for qPCR detection for STEC (i.e., analyzing for presence/absence). When run by qPCR, positive controls consisted of duplicate wells of plasmid DNA with the respective STEC target (stx1 and stx2),39 while negative controls consisted of no-template controls. All positive controls were consistently positive. The rationale for incorporating a culture-based assay prior to qPCR was to increase the chances of finding STEC within stormwater samples by selectively enriching growth of the E. coli population in these samples.

2.4. qPCR

TaqMan chemistry-based quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) methods were used to test for enteric pathogens A. butzleri (hsp60),8Campylobacter spp. (VD16S),40Salmonella spp. (invA)41 and STEC (stx1 and stx2).39 In addition, source tracking markers were also tested, including for human sewage (HF18342 and HumM243), dogs,44 gulls,45 Canada geese,46 ruminants,47 and muskrats48 (see Table S3 in Supporting Information File 1).

2.4.1. qPCR Sample Preparation

DNA extraction of water samples first began by filtering 20 mL of stormwater samples on polycarbonate 0.4 μm-pore MicroFunnel (Pall Corporation, New York). Filtered samples were extracted by the U.S. EPA Method 1611 protocol,38 as described here in brief. These filters were added to bead tubes (Generite, North Brunswick, NJ) containing AE buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 9.0) (QIAGEN; Hilden, Germany), as well as 0.2 μg/mL of O. keta (Salmon) sperm as an internal control. Sample filters were further processed with a Bead Mill 24 Homogenizer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts), before individual supernatants were transferred and centrifuged twice (at 12,000 X g). This final supernatant was used as the qPCR template and was stored at −80 °C (no longer than 12 months) until qPCR was run.

2.4.2. qPCR Reaction Conditions

All qPCR reactions were carried out on an Applied Biosystems(R) 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR (Applied Biosystems(R); ThermoFisher Scientific, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada). Each qPCR test was performed as a 2-step reaction with cycling conditions; 3 min of denaturation at 95 °C, followed by 40 individual cycles of denaturation and annealing/extension at 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s, each. Forty cycles were used for all qPCR reactions against the molecular targets in stormwater samples. For all MPN qPCR assays, the number of cycles was reduced to 35, due to increased sensitivity associated with the selective growth enrichment for A. butzleri in the MPN assay. The reagents used included 1x PrimeTime(R) GeneExpression Master Mix (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, Iowa), 200 μg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mississippi), and primers and probes (as described as Table S3 in Supporting Information File 1). All qPCR runs used MicroAmp Fast Optical 96-well plates (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California), and consisted of 20 μL reactions (15 μL of reagents to 5 μL of template).

2.4.3. qPCR Controls

Positive controls for qPCR methods included plasmid standard dilutions for each individual marker, which were serially diluted by a factor of 10 and ranged from 50,000 copies/reaction to 5 copies/reaction. Negative controls included filter blanks (filtered PBS) and no-template controls (NTC – nuclease-free water). All filter blanks were negative for amplification. Inhibition in stormwater samples was assessed based on U.S. EPA Method 161138 which incorporates Oncorhynchus keta DNA (known as the Sketa assay38,49) as an internal amplification control. If the Sketa Ct of individual samples was found to be ≥3 from the Ct average, these samples were considered inhibited.38 Inhibited samples were diluted to 1:5 and 1:25 of original sample concentrations, and run again, in an effort to overcome inhibition when possible. Only 4 of 743 samples within this study were found to be inhibited within this study, and only two were inhibited to a degree that this inhibition could not be overcome with dilution (both samples from McCall Lake). These two samples were therefore discarded from analysis. For further information on the number of replicates and quality control characteristics of the qPCR methods used in this study, including criteria such as slope, R2 value, Y-intercept, and amplification efficiency values, see Supporting Information File 2 entitled ‘qPCR Quality Control Data and Limits of Detection’.

2.4.4. Standard Curve Plasmid Sources and Construction

DNA plasmid standard controls for each assay were prepared prior to this study. In brief, individual assay target amplicons were sourced from the appropriate host’s fecal samples, or else purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Newark, NJ) as synthetic genes (in the case of the CGO1 assay46). These targets were amplified by PCR using their respective primers before being resolved in a 2% agarose gel and extracted with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Amplicons were cloned with the TOPO(TM) TA cloning kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), as per manufacturer instructions. Once cloned, the plasmid DNA was isolated with the QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and sequenced at the University of Alberta (TAGC facility) to confirm the presence of the correct insert. Once this was confirmed, cloned plasmids were enumerated using the Qubit 2.0 fluorimeter (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and diluted to stock concentrations of 100,000 plasmid copy/μL. Plasmid stocks were stored at −80 °C, and were aliquoted and diluted by 10-fold serial dilution into the appropriate concentrations for each individual target when qPCR was run.

2.5. Isolation and Characterization of A. butzleri from Stormwater

2.5.1. Isolation of A. butzleri

Analysis and characterization of individual A. butzleri isolates began by first subsampling 500 μL from MPN wells that were positive for the A. butzleri hsp60 assay (See 2.2), and adding these to 500 μL of a 1:1 mixture of skim milk:glycerol. These samples were then stored at −80 °C until a later date (<6 months later), before they were unfrozen and cultured on BB media plates (including BB selective supplements [ThermoFisher Scientific, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada]) at 30 °C for 48 h under microaerophilic conditions. Individual colonies (n = 85) were then selected and placed into liquid medium (BB with BB selective supplements), being further incubated at 30 °C for 48 h, again in microaerophilic conditions. Finally, 100 μL of each sample was boiled at 95 °C for 10 min to lyse cells, and this was the final DNA extract used for qPCR testing of nine putative virulence genes and for ERIC-PCR. Isolates were confirmed to be A. butzleri by positive test of the hsp60 assay, with the addition of the same IAC test as described above.

2.5.2. ERIC-PCR

Enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus – PCR (ERIC-PCR) was utilized in determining the genetic similarity between A. butzleri isolates sourced from stormwater. ERIC-PCR reactions were run as 25 μL reactions using conditions and reagents adapted from Houf et al.50 Briefly, reactions consisted of 1.25 μL of the ERIC-F primer, 1.25 μL of the ERIC-R primer, 2.5 μL of 10X PCR Buffer (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA), 0.5 μL of 40 mM dNTP mixture, 2 μL of 40 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μL of 5U Taq Polymerase (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA), 15.5 μL of PCR-grade water, and 1.5 μL of DNA template (see Table S4 in Supporting Information File 1 for primer sequences and concentrations). The Applied Biosystems(R) 2720 Thermal Cycler (ThermoFisher Scientific, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) was used to perform reactions using the following conditions: an initial denaturation of 94 °C for 5 min, before 40 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 25 °C for 1 min, and elongation at 72 °C for 2 min. End point PCR products were diluted 1:10 in DNA dilution buffer, before gel electrophoresis was run on the QIAxcel Advanced capillary electrophoresis system (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) against DNA size markers of 250 bp −8 kbp (diluted in DNA dilution buffer to 1:20), as well as a DNA alignment marker of 15 bp −10 kbp.

2.6. Putative Virulence Gene Analysis

All A. butzleri isolates (n = 73) originating from positive MPN wells (as confirmed with the A. butzleri hsp60 assay) and that were typed by ERIC-PCR were screened for the putative virulence genes cadF and ciaB. Isolates positive for cadF and/or ciaB were further screened for seven other putative virulence genes, including mniV, cj 1349, irgA, hecA, hecB, pldA, and tylA, for nine genes total, in methods adopted from Douidah et al. (see Table S5 in Supporting Information File 1).51

2.6.1. Virulence Gene PCR

PCR reactions were performed at a volume of 25 μL each (5 μL template plus 20 μL reagents), and reagents consisted of 5 μL of 2× Maxima Hot Start PCR MasterMix (Thermofisher, Waltham, MA), 5 μL of nuclease-free water, and 10 μL of each appropriate primer (each at 1 μM concentration) (See Table S5 in Supporting Information File 1).51 An Applied Biosystems(R) 2720 Thermal Cycler (ThermoFisher Scientific, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) was used, with each reaction consisting of 35 cycles, and each cycle including denaturation at 94 °C for 20 s, annealing at 58 °C for 45 s, and extension at 72 °C for 20 s, before a 4 °C hold. After 35 cycles, samples were heated to 94 °C for 4 min. PCR products then underwent gel electrophoresis at 150 V for 45 min through a 1% agarose gel in Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer, before the gel was stained with SYBR Safe DNA gel stain (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and imaged using an ImageQuant Las 400 UV transilluminator (GE HealthCare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). A 100 base pair marker was used as a positive control to compare to finished PCR products within individual gels.

2.7. Data Analysis

Quantitative data (i.e., Ct values) from qPCR were determined by manually setting a Ct threshold for each assay (see Table S6 in Supporting Information File 1) for comparison between known standard curve values and unknown sample values. Estimates of qPCR marker concentrations, as well as most-probable-number (MPN) estimates were first normalized per volume (100 mL or per 300 mL) of stormwater collected, before data analysis began. All data was log10-transformed.

To determine assay sensitivity, we determined the limit of detection with 95% confidence intervals (LOD95) of each qPCR target using the methods of Wilrich and Wilrich52 (See Supporting Information File 2–qPCR Quality Control Data and Limits of Detection). For direct qPCR from DNA extracted from stormwater samples, marker estimates were designated as nondetects (ND) [or negative] if there was no detection after 40 cycles of amplification (i.e., amplification values similar to the no template controls [NTC]). Samples were deemed positive if they fell within the detectable but not quantifiable (DNQ) range (i.e., below the LOD95 but with amplification greater than no template controls after 40 cycles) or if amplification was in the quantifiable range (i.e., above LOD95).

The theoretical limit of detection (LOD) for the miniaturized-MPN assay was 0.36 MPN/300 mL, as calculated with standard MPN tables. Samples tested by MPN were considered “positive” if ≥0.36 MPN/300 mL was detected (i.e., one well qPCR positive in the lowest MPN dilution), whereas MPN samples were considered “negative” (<0.36 MPN/300 mL) if no qPCR detection of A. butzleri was observed in any of the wells. Geometric means for qPCR marker estimates were calculated by discounting ND results, and setting DNQ results as equal to the lowest standard dilution being 5 copies/rxn (i.e., lowest dilution of standard curve of positive controls, and equivalent to 3.48 log10 copies/100 mL).

2.7.1. Statistical Analysis

Pearson’s χ2 test was used for several analyses, including comparing detection of A. butzleri between stormwater-impacted ponds in Calgary, comparing detection of human sewage marker HF183 between stormwater-impacted ponds in Calgary, comparing HF183 detection in Calgary and Airdrie stormwater against detection of other animal markers, and comparing A. butzleri detection versus HF183 detection in Calgary and Airdrie stormwater. In the latter test, the φ correlation coefficient was also used to determine the effect size when comparing A. butzleri detection and HF183 detection. In addition to the above, simple linear regression was used to analyze concentration differences of HF183 and A. butzleri (i.e., the hsp60 marker) between Calgary stormponds, as well as any correlation these two markers may have. McNemar’s test was used to determine whether the discordance between culture (miniaturized MPN) and molecular-based (qPCR) methods used in this study were significant in a subset of samples from McCall Lake in Calgary. In all cases of statistical testing, α error was set to 5% (i.e., p < 0.05 for results to be considered significant), though the Bonferroni correction was additionally used when multiple comparisons were made.

2.7.2. Additional Quality Control

In an effort to support reporting transparency and methodological quality control, the ‘Environmental Microbiology Minimum Information (EMMI) checklist’, as devised by Borchardt et al.,53 has been provided under Supporting Information File 3 – EMMI checklist. This document provides a simplified description of this study (both the direct qPCR and miniaturized MPN-qPCR assay), including a general workflow of all controls and processes.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence and Concentrations of A. butzleri in Stormwater

Arcobacter butzleri was the most frequently detected bacterial pathogen (among Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp., and STEC) in stormwater samples collected from Calgary, and Airdrie, Alberta (see Tables 1 and 2). In Calgary, A. butzleri was detected by molecular methods in 146 of 531 (27.5%) total samples collected in 2017, while this pathogen was found in 39 of 126 samples (31.0%) in Airdrie stormwater in 2021, and in only 2 of 84 samples (2.4%) from Airdrie in the preceding year of 2020 (Table 1). In Calgary, A. butzleri marker concentrations (i.e., the single copy gene hsp60) ranged from not detectable (ND) to 5.0 log10 copies/100 mL, with a geometric mean of 3.8 log10 copies/100 mL, while this range was from ND to 6.2 log10 copies/100 mL (geometric mean of 3.8 log10 copies/100 mL) in Airdrie stormwater (Table 1). In Calgary, statistically significant differences of A. butzleri detection (by the χ2 test) were noted between stormwater ponds (p = 0.006). For example, after the application of the Bonferroni correction for further pairwise comparisons using χ2, McCall Lake was found to have significantly greater A. butzleri detection than both Country Hills (p = 0.003) and Inverness (p = 0.016), though there were no significant differences between Country Hills and Inverness. When concentrations of A. butzleri in Calgary were analyzed by simple linear regression, McCall Lake had significantly higher concentrations of A. butzleri (by 0.2 log10 copies/100 mL on average) than the Country Hills Stormpond (p = 0.007), though there were no other significant differences in concentrations between McCall Lake and Inverness, or Inverness and Country Hills.

Table 1. Frequency of Detection, Geometric Means, and Concentration Ranges of A. butzleri and Campylobacter spp., as Estimated by Quantitative PCR (qPCR) in Southern Alberta Stormwater Collected from Various Urban Ponds and Creeks in Calgary and Airdrie.

|

A.

butzleri |

Campylobacter spp. |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsp60 | VD16S | |||||||

| city | stormwater pond | n | detection frequency (%) | geometric mean (log10 copies/100 mL) | range (log10 copies/100 mL) | detection frequency (%) | geometric mean (log10 copies/100 mL) | range (log10 copies/100 mL) |

| Calgary | McCall Lake | 162 | 60/162 (37.0) | 3.89 | ND - 4.81 | 11/162 (6.8) | 3.56 | ND - 4.37 |

| Inverness | 164 | 40/164 (24.4) | 3.80 | ND - 5.00 | 2/164 (1.2) | 3.92 | ND - 4.37 | |

| Country Hills | 205 | 46/205 (22.4) | 3.68 | ND - 4.55 | 10/205 (4.9) | 3.65 | ND - 4.37 | |

| Calgary total | 531 | 146/531 (27.5) | 3.80 | ND - 5.00 | 23/531 (4.3) | 3.63 | ND - 4.37 | |

| Airdrie | Nose Creek | 38 | 21/38 (55.3) | 3.64 | ND - 4.13 | 3/38 (7.9) | 3.57 | ND - 3.75 |

| Windsong | 44 | 6/44 (13.6) | 4.51 | ND - 6.21 | 1/44 (2.3) | N/A | ND - DNQ | |

| Canals | 40 | 8/40 (20.0) | 3.80 | ND - 4.40 | 1/40 (2.5) | N/A | ND - 3.54 | |

| King’s Heights North | 8 | 3/8 (37.5) | 4.09 | ND - 4.86 | 1/8 (12.5) | N/A | ND - 3.58 | |

| King’s Heights South | 12 | 2/12 (16.7) | 3.51 | ND - 3.55 | 1/12 (8.3) | N/A | ND - DNQ | |

| East Lake | 56 | 1/56 (1.8) | N/A | ND - DNQ | 7/56 (12.5) | 3.51 | ND - 3.61 | |

| Hillcrest | 12 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Airdrie total | 210 | 41/210 (19.5) | 3.82 | ND - 4.86 | 14/210 (6.7) | 3.52 | ND - 3.75 | |

| grand total | 741 | 187/741 (25.2) | 3.80 | ND - 6.21 | 27/741 (3.6) | 3.59 | ND - 4.37 | |

Table 2. Frequency of STEC and Salmonella spp. Detection by Quantitative PCR (qPCR) in Southern Alberta Stormwater Collected from Various Urban Ponds and Creeks in Calgary and Airdrie.

| STEC | Salmonella spp. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| stx1 and stx2 | invA | |||

| City | Stormwater Pond | n | detection frequency (%)a | detection frequency (%)b |

| Calgary | McCall Lake | 162 | 20/162 (12.3) | 2/162 (1.2) |

| Inverness | 164 | 8/164 (4.9) | 1/164 (0.6) | |

| Country Hills | 205 | 16/205 (7.8) | 1/205 (0.5) | |

| Calgary Total | 531 | 44/531 (8.3) | 4/531 (0.8) | |

| Airdrie | Nose Creek | 38 | 0 | 0 |

| Windsong | 44 | 2/44 (4.5) | 0 | |

| Canals | 40 | 0 | 0 | |

| King’s Heights North | 8 | 0 | 0 | |

| King’s Heights South | 12 | 0 | 0 | |

| East Lake | 56 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hillcrest | 12 | 0 | 0 | |

| Airdrie total | 210 | 2/210 (1.0) | 0 | |

| Grand total | 741 | 46/741 (6.2) | 4/741 (0.5) | |

Data for STEC is based on presence/absence data from culture and/or direct qPCR results.

All detections for Salmonella by qPCR were at the DNQ range.

The McCall Lake stormwater pond in Calgary was used to gather culturable estimates of A. butzleri in stormwater (Table 3), as well as compare qPCR detection frequency to culturable estimates of detection of this same pathogen (Table 3). As can be observed in Table 3, the frequency of detection of A. butzleri by culture was higher than that observed by qPCR in stormwater collected from McCall Lake (26 of 32 samples, 81.3%), but culturable cell estimates showed relatively low concentrations overall, with no sample having an A. butzleri concentration greater than 2.0 log10 MPN/300 mL, and a site-specific mean of <1.3 log10 MPN/300 mL for all sites. In contrast to 81.3% of samples having culturable A. butzleri, only 10 of these same 32 samples (31.3%) were positive for A. butzleri by qPCR on the same subset of samples, with concentrations ranging from DNQ to 4.6 log10 copies/100 mL. According to McNemar’s test, the MPN assay for culturable A. butzleri was significantly more likely to detect this pathogen than the qPCR assay (p = 0.0001), with these assays therefore providing discordant results (Table S7). Taken together, the above results suggest that estimates of prevalence for A. butzleri are much higher when culture-based methods are used compared to the molecular-based testing methods from water filtrates, and this is likely due to the overall greater volumes of stormwater analyzed with culture-based methods compared to molecular-based methods.

Table 3. Culture-Based Detection of A. butzleri Detection (Miniaturized-MPN-qPCR Assay) from the McCall Lake Stormwater Pond in Calgary, Studied in 2017.

| arithmetic mean | range | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| McCall Lake Sampling Site | n | frequency of positive detections (%)a | MPN/300 mL | |

| ML1 | 8 | 6/8 (75.0%) | 7.3 | NDb - 43 |

| ML2 | 8 | 8/8 (100.0%) | 18 | 0.9–93 |

| PR60 | 8 | 6/8 (75.0%) | 3.5 | NDb - 17 |

| Inlet 3/4 | 8 | 6/8 (75.0%) | 4.2 | NDb - 18 |

| total | 32 | 26/32 (81.3%) | 8.0 | NDb - 93 |

Samples with greater than the LOD of the MPN assay (0.36 MPN/300 mL) were considered positive.

ND = Not detected.

3.2. Microbial Source Tracking (MST) Marker Associations with A. butzleri

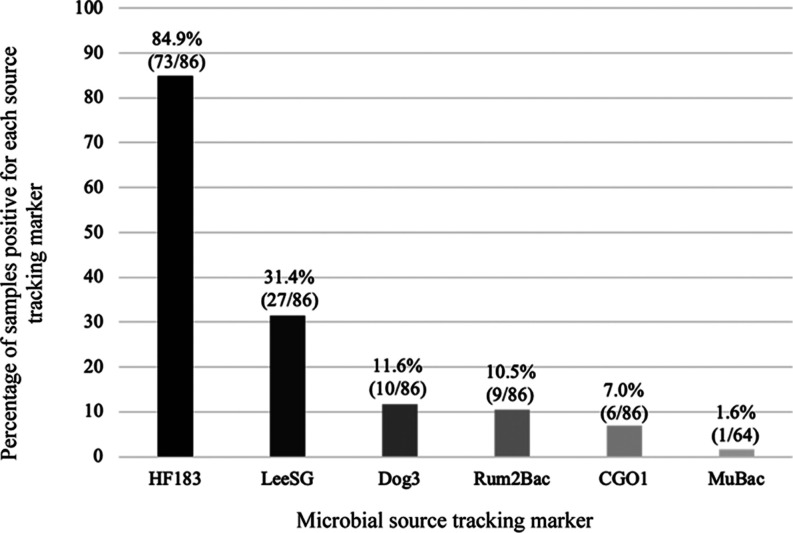

In stormwater sampled from both Airdrie and Calgary, Alberta, the primary fecal source detected in both cities was human sewage (i.e., HF183), and found at a prevalence of 18.1% (38 of 210) and 28.6% (152 of 531) in each city, respectively, although identifiable sources of fecal pollution also included gulls, Canada geese, muskrats, dogs, and ruminants (Table 4). The human sewage marker, HF183, had an overall geometric mean concentration of 3.79 log10 copies/100 mL, and ranged from ND to as high as 6.0 log10 copies/100 mL, with this higher concentration found in one outfall of McCall Lake (ML#2–see Table S8, Supporting Information File 1). In stormwater samples that were positive for A. butzleri, the human fecal marker HF183 was the most dominant fecal marker to be found when compared to any of the other animal markers for both Calgary (p < 0.0001 for all comparisons by χ2) and Airdrie (p < 0.05 for all comparisons by the same test), suggesting that A. butzleri was frequently found alongside human sewage (Table 5, Figure 1). Indeed, in all A. butzleri positive samples that were also positive for one or more MST markers, the human sewage marker HF183 was found in 84.6% of samples (Figure 1). Additionally, HF183 could sometimes mirror the occurrence pattern seen for A. butzleri. For example, McCall Lake was noted as having the highest prevalence of the human fecal marker HF183 compared to other ponds in Calgary (i.e., χ2 test when compared to Country Hills [p = 0.002] and Inverness [p < 0.001]) and which also had the highest occurrence of A. butzleri. These results are mirrored by simple linear regression results, which show that HF183 concentrations were significantly higher in McCall Lake than Country Hills (p = 0.024) and the Inverness (p < 0.001) stormwater ponds, though Inverness HF183 concentrations were also significantly higher on average than concentrations in Country Hills (p = 0.033). When detection of the human sewage marker HF183 and A. butzleri were compared and examined by χ2 within all samples taken from Calgary (Table S9, Supporting Information File 1) and Airdrie (Table S10, Supporting Information File 1), there was a significant association (p < 0.05) between A. butzleri and HF183, though low φ correlation values (φ < 0.4) indicated a weak (albeit still significant) relationship between these two parameters. Notably, there was no significant relationship found between A. butzleri concentrations and HF183 concentrations by simple linear regression, however.

Table 4. Percentage of Microbial Source Tracking (MST) Marker Detection by Quantitative PCR (qPCR) in Southern Alberta Stormwater Collected from Various Urban Ponds and Creeks in Calgary and Airdrie.

| Human |

Gull | Canada Goose | Dog | Ruminant | Muskrat | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Stormwater Pond | n | HF183 | HumM2 | LeeSG | CGO1 | Dog3 | Rum2Bac | MuBac |

| Calgary | McCall Lake | 162 | 71/162 (43.8%) | 34/162 (21.0%) | 25/162 (15.4%) | 7/162 (4.3%) | 5/162 (3.1%) | 4/162 (2.5%) | 1/162 (0.6%) |

| Inverness | 164 | 24/164 (14.6%) | 5/164 (3.1%) | 7/164 (4.3%) | 2/164 (1.2%) | 1/164 (0.6%) | 1/164 (0.6%) | 2/164 (1.2%) | |

| Country Hills | 205 | 57/205 (27.8%) | 17/205 (8.3%) | 20/205 (9.8%) | 3/205 (1.5%) | 7/205 (3.4%) | 6/205 (2.9%) | 4/205 (2.0%) | |

| Calgary Total | 531 | 136/531 (25.6%) | 52/531 (9.8%) | 52/531 (9.8%) | 11/531 (2.1%) | 13/531 (2.4%) | 11/531 (2.1%) | 6/531 (1.1%) | |

| Airdrie | Nose Creek | 38 | 22/38 (57.9%) | 10/38 (26.3%) | 3/38 (7.9%) | NDa | 6/38 (15.8%) | 6/38 (15.8%) | N/Ab |

| Windsong | 44 | 6/44 (13.6%) | 1/44 (2.3%) | 3/44 (6.8%) | 1/44 (2.3%) | 2/44 (4.5%) | 1/44 (2.3%) | N/Ab | |

| Canals | 40 | 3/40 (7.5%) | NDa | NDa | 3/40 (7.5%) | 3/40 (7.5%) | NDa | N/Ab | |

| King’s Heights North | 8 | 1/8 (12.5%) | NDa | NDa | NDa | 1/8 (12.5%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | N/Ab | |

| King’s Heights South | 12 | NDa | NDa | NDa | NDa | 1/12 (8.3%) | 2/12 (16.7%) | N/Ab | |

| East Lake | 56 | 3/56 (5.4%) | NDa | 7/56 (12.5%) | 1/56 (1.8%) | 1/56 (1.8%) | NDa | N/Ab | |

| Hillcrest | 12 | 3/12 (25.0%) | 1/12 (8.3%) | 1/12 (8.3%) | NDa | 2/12 (16.7%) | 2/12 (16.7%) | N/Ab | |

| Airdrie total | 210 | 38/210 (18.1%) | 12/210 (5.7%) | 14/210 (6.7%) | 5/210 (2.4%) | 16/210 (7.6%) | 12/210 (5.7%) | N/Ab | |

| grand total | 741 | 174/741 (23.5%) | 64/741 (8.6%) | 66/741 (8.9%) | 16/741 (2.2%) | 29/741 (3.9%) | 23/741 (3.1%) | N/Ab | |

ND = Not detected.

N/A = Not applicable (i.e., marker not tested for in samples from Airdrie, Alberta).

Table 5. Percentage of A. butzleri Positive Stormwater Samples from Calgary and Airdrie that were also Positive for the Designated MST Markers.

| Human |

Gull | Canada Goose | Dog | Ruminant | Muskrat | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Stormwater Pond | n | HF183 | HumM2 | LeeSG | CGO1 | Dog3 | Rum2Bac | MuBac |

| Calgary | McCall Lake | 60 | 34/60 (56.7%) | 16/60 (26.7%) | 18/60 (30.0%) | 3/60 (5.0%) | 3/60 (5.0%) | 2/60 (3.3%) | 1/60 (1.7%) |

| Inverness | 40 | 9/40 (22.5%) | 2/40 (5.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Country Hills | 46 | 13/46 (28.3%) | 4/46 (8.7%) | 4/46 (8.7%) | 2/46 (4.4%) | 0 | 1/46 (2.2%) | 0 | |

| Calgary Total | 146 | 56/146 (38.4%) | 22/146 (15.1%) | 22/146 (15.1%) | 5/146 (3.4%) | 3/146 (2.1%) | 3/146 (2.1%) | 1/146 (0.7%) | |

| Airdrie | Nose Creek | 21 | 16/21 (76.2%) | 4/21 (19.0%) | 3/21 (14.3%) | NDa | 6/21 (28.6%) | 5/21 (23.8%) | N/Ab |

| Windsong | 6 | 1/6 (16.7%) | 0 | 2/6 (33.3%) | 0 | 1/6 (16.7%) | 0 | N/Ab | |

| Canals | 8 | 0 | NDa | NDa | 1/8 (12.5%) | 0 | NDa | N/Ab | |

| King’s Heights North | 3 | 0 | NDa | NDa | NDa | 0 | 1/3 (33.3%) | N/Ab | |

| King’s Heights South | 2 | NDa | NDa | NDa | NDa | 0 | 0 | N/Ab | |

| East Lake | 1 | 0 | NDa | 0 | 0 | 0 | NDa | N/Ab | |

| Hillcrest | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/Ab | |

| Airdrie total | 41 | 17/41 (41.5%) | 4/41 (9.8%) | 5/41 (12.2%) | 1/41 (2.4%) | 7/41 (17.1%) | 6/41 (14.6%) | N/Ab | |

| grand total | 187 | 73/187 (39.0%) | 26/187 (13.9%) | 27/187 (14.4%) | 6/187 (3.2%) | 10/187 (5.3%) | 9/187 (4.8%) | N/Ab | |

ND = Not detected.

N/A = Not applicable (i.e., marker not tested for in samples from Airdrie, Alberta).

Figure 1.

Proportion of samples that were positive for each source tracking marker, out of a pool of samples positive for A. butzleri and also positive for at least one source-tracking marker (i.e., excluding all A. butzleri-negative and source tracking-negative samples [n = 86]). Note that MuBac was only tested in Calgary samples (n = 64).

3.3. Putative Virulence Gene Prevalence in A. butzleri Isolates

The clonal variation of A. butzleri strains cultured from McCall Lake stormwater samples was assessed using ERIC-PCR, and each unique clone (i.e., based on unique ERIC-PCR banding patterns) was tested against 9 putative virulence genes of A. butzleri. ERIC-PCR revealed a diverse repertoire of clonally represented strains of A. butzleri in stormwater (See Figure S9 in Supporting Information File 1 for an example), with 73 unique clonal strains found in the 26 samples that were culture-positive for A. butzleri [of 32 samples tested]. Putative virulence genes were frequently detected in these unique isolates, with a prevalence of all 9 virulence genes being detected in 21 of the 73 (28.8%) isolates, and with 50 of 73 (68.3%) isolates being positive for 8 or more virulence genes (Figure S10). Each individual virulence gene was also found in the majority of isolates, with ciaB being found in every single isolate, while cadF, cj1349, pldA, and tylA were all found in >90% of the 73 isolates (Table S11). This suggested a wide genetic diversity of potentially pathogenic A. butzleri in stormwater.

4. Discussion

Arcobacter butzleri is an emergent human gastrointestinal pathogen of concern, commonly found in human sewage,19−24 and whose abundance and occurrence in environmental waters is becoming a growing concern.25−29,33 Unfortunately, very little is currently understood about Arcobacter butzleri with regards to its pathogenicity, epidemiology in humans, and dose–response modeling.5,54Arcobacter infections are also underassessed in humans due to the fact that the organism can be mistaken for Campylobacter spp., as it is able to grow under similar conditions and some molecular-based assays do not accurately differentiate the two genera.28,55,56

Herein we demonstrate that A. butzleri is a common constituent of stormwater. Across 743 stormwater samples analyzed by qPCR, 187 samples (25.2%) were positive for A. butzleri, whereas only 46 (6.2%), 27 (3.6%), and 4 samples (0.5%) were positive for STEC, Campylobacter spp., and Salmonella spp., respectively (Tables 1 and 2). Based on qPCR analysis of the hsp60 gene concentration in stormwater, the level of A. butzleri appeared to be quite high on occasion (i.e., > 6 log10 gene copies/100 mL) and higher than that observed for the other pathogens. The hsp60 gene encodes a chaperone (heat shock protein-60) that is conserved across all A. butzleri strains regardless of pathogenicity and this is in contrast to the assays for Salmonella and STEC which specifically target genes encoding virulence factors (invA and stx1/stx2 respectively), suggesting that the hsp60 assay may overestimate the occurrence of pathogenic A. butzleri in stormwater. However, PCR analysis of 9 virulence genes commonly found in clinical A. butzleri showed that all 73 unique strains of A. butzleri isolated from stormwater carried the ciaB virulence gene. The virulence genes cadF, cj1349, pldA, and tylA were also found at >90% prevalence rates in these same isolates. This suggests that a substantial proportion of the A. butzleri observed in stormwater is likely pathogenic.

Interestingly, in a subset of samples cultured for A. butzleri (i.e., MPN-qPCR assay [n = 32]), an even higher prevalence was observed (i.e., >80%) when compared to direct qPCR (25.2%), implying an extremely ubiquitous presence of this pathogen in stormwater (Table S7). In this subset of samples, cultured for A. butzleri (n = 32), a relatively low concentration of culturable/viable A. butzleri were observed across all samples (the highest concentration being 93 bacteria/300 mL), albeit molecular assays for these same samples generally displayed low to nondetectable levels of hsp60 gene copy numbers in these same samples. One simple explanation for this difference in sensitivity between the MPN and qPCR assays was the fact that a much higher proportion of the stormwater sample was tested for the MPN assays compared to direct qPCR testing. In the case of qPCR, only about 1/120th of a 20 mL reconstituted stormwater sample is actually tested in each qPCR reaction (i.e., 5 μL of a total DNA extract volume of 600 μL) This is equivalent to analyzing only 167 μL of a 20 mL stormwater sample, whereas in our MPN assay 300 mL of stormwater is tested. Additionally, since the selective enrichment step of the MPN assay allows for replication of the organism over time, this may also explain why MPN culture-based sensitivity was greater. Given the ubiquitous nature of pathogenic A. butzleri in stormwater, and at potentially high concentrations, further work is needed to characterize the occurrence and abundance of A. butzleri in stormwater for improving microbial risk assessments around stormwater use.

In our study within Alberta, and as reported by many other studies on stormwater elsewhere,32,57−65 human sewage pollution was found to be the dominant source of fecal pollution contaminating urban stormwater, even in cities where sanitary sewer and stormwater sewer infrastructure have been built separately, such as in the urban municipalities examined within this study. Indeed, in samples positive for A. butzleri, the human sewage marker HF183 was the most frequently observed fecal marker in these samples when compared to other source tracking markers targeting gulls, geese, dogs, ruminants and muskrats. Likewise, in stormwater ponds where human sewage contamination was deemed the highest–i.e., based on frequency of detection and concentrations of HF183 (i.e., McCall Lake) – A. butzleri was also statistically more prevalent. Conversely, A. butzleri was also detected infrequently in other stormwater ponds such as East Lake in Airdrie (1 of 56 samples), where human fecal pollution was infrequently detected as well (i.e., 3 of 56 samples) (Tables 4 and 5). The data suggests that sewage contamination is likely a dominant source of A. butzleri loading in stormwater. Importantly, A. butzleri and other pathogenic Arcobacter species such as A. cryaerophilus, represent dominant bacterial populations in sewage, with concentrations of Arcobacter being reported as ≥107 cells per 100 mL.19,66,67

Studies have demonstrated that stormwater can be comprised with as much as 10% sewage,32,58,63,68 even in systems separate from sanitary, and based on comparing the concentrations of HF183 found in the stormwater to that typically seen in raw human municipal sewage.69,70 Stormwater coming from Airdrie and Calgary was consistent with these estimates, with concentrations representing flows of 0.1% to as high as 10% raw human sewage, as seen in the ML2 outfall of the McCall Lake stormpond in Calgary. Human sewage infiltration into urban stormwater networks can occur as a result of: (a) broken and aging sanitary sewer infrastructure,68 (b) illicit cross-connections,58 (c) illegal dumping of sewage into stormwater drains from recreational vehicles or portable waste systems, (d) homeless or vulnerable populations lacking access to waste management systems, and (e) combined sewer overflows.60,71 Studies have demonstrated the utility of source-tracking human fecal pollution signatures in storm drainage networks in order to pinpoint these sources of sewage pollution.58,68

A. butzleri was also detected in samples that lacked detection of source tracking markers for human sewage, and the lower effect size (φ < 0.4, see Tables S9 and S10, Supporting Information File 1) of the significant relationship between A. butzleri and HF183 reflected the fact that other animal reservoirs may also contribute A. butzleri loading into stormwater drainage systems.12−16 Important animal host reservoirs of A. butzleri that may be pertinent to urban stormwater drainage include dogs,15 geese,12 and cats.72

Our overall knowledge on pathogen occurrence, and the consequent risks of using stormwater is currently incomplete. For example, few risk-assessment studies have been done on stormwater use.62,73−76 Notably, bacterial reference pathogens typically used in risk assessment studies include Campylobacter spp. (usually C. jejuni, specifically), and/or Salmonella enterica.62,73−76 However, the concentrations of these enteric pathogenic bacteria referenced in quantitative microbial risk assessments studies e.g., (i.e., ∼103 to 104Campylobacter spp. per 100 mL)75 are several orders of magnitude lower than the concentration of Arcobacter spp. found in raw sewage (i.e., 107 per 100 mL).19,66,67 Moreover, our observation that A. butzleri concentrations in stormwater may be >106 organisms per 100 mL (based on qPCR of the hsp60 target) implies a potential underestimation of bacterial enteric risks associated with stormwater use from these previous risk assessment studies.

For the above reasons, we contend that A. butzleri (or Arcobacter spp. in general) may be an important reference pathogen for modeling bacterial disease risks associated with stormwater use (and wastewater reuse), due to the fact that (a) Arcobacter are far more abundant in both stormwater (this study) and municipal sewage19−24 when compared to Campylobacter spp., or Salmonella spp.; (b) Arcobacter loading in stormwater appears to come primarily from human sewage, and is therefore representative of human health risks associated with exposure to contaminated stormwater use; (c) A. butzleri has been found to correlate well with human sewage indicators,19,26,31 and fecal indicator bacteria,26,27,29 while pathogens such as Campylobacter and Salmonella do not correlate well with either human sewage markers19,65,77 or fecal indicators;40,73,77 (d) A. butzleri isolates collected from stormwater (i.e., this study) and other environmental waters78 appear to be pathogenic in nature; (e) A. butzleri are capable of surviving for long periods of time in water4; (f) A. butzleri may be able to grow in nonhost environments such as water;35 and (g) A. butzleri displays a similar clinical disease phenotype as Campylobacter spp.

Future efforts should focus on a detailed assessment of the occurrence of pathogenic A. butzleri in aquatic environments such as stormwater in order to better assess public health risks associated with stormwater use.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by grants to N.F.N., C.V. and J.H. from Alberta Innovates (Project Number AI-EES2333), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) University of Alberta Project Number: NSERC CRDPJ 520869-17, City of Calgary (University of Alberta Project Number: CC CRD 520869), and through in-kind logistic support from the City of Airdrie, Alberta, Canada. Other than affiliation of some authors to municipal-level funding agencies (B.v.D. [City of Calgary] and C.G. [City of Airdrie]) the funding agencies themselves did not play a role in study design, data collection and analysis, or decision to publish. The authors would like to give special thanks to the environmental monitoring team of the City of Airdrie (Kevin Kerr, Jennifer Sugden, Terry Parks, and Kelly McKague), for the coordination, organization, and performance of on-site sampling for both investigative and routine samples.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.4c01358.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Vandamme P.; Falsen E.; Rossau R.; Hoste B.; Segers P.; Tytgat R.; De Ley J. Revision of Campylobacter, Helicobacter, and Wolinella taxonomy: Emendation of generic descriptions and proposal of Arcobacter gen. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1991, 41 (1), 88–103. 10.1099/00207713-41-1-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandamme P.; Vancanneyt B.; Pot B.; Mels L.; Hoste B.; Dewettinck D.; Vlaes L.; Van den Borre C.; Higgins R.; Hommez J.; Kersters K.; Butzler J.-P.; Goossens H. Polyphasic taxonomic study of the emended genus Arcobacter with Arcobacter butzleri comb. nov. and Arcobacter skirrowii sp. nov., an aerotolerant bacterium isolated from veterinary specimens. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1992, 42 (3), 344–356. 10.1099/00207713-42-3-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fera M. T.; Maugeri T. L.; Gugliandolo C.; La Camera E.; Lentini V.; Favaloro A.; Bonanno D.; Carbone M. Induction and resuscitation of viable nonculturable Arcobacter butzleri cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74 (10), 3266–3268. 10.1128/AEM.00059-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Driessche E.; Houf K. Survival capacity in water of Arcobacter species under different temperature conditions. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 105 (2), 443–451. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chieffi D.; Fanelli F.; Fusco V. Arcobacter butzleri: Up-to-date taxonomy, ecology, and pathogenicity of an emerging pathogen. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19 (4), 2071–2109. 10.1111/1541-4337.12577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira S.; Júlio C.; Queiroz J. A.; Domingues F. C.; Oleastro M. Molecular diagnosis of Arcobacter and Campylobacter in diarrhoeal samples among Portuguese patients. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 78 (3), 220–225. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arguello E.; Otto C. C.; Mead P.; Babady N. E. 2015. Bacteremia caused by Arcobacter butzleri in an immunocompromised host. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 1448–1451. 10.1128/JCM.03450-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer R. F.; Ott A.; Güren P.; van Zanten E.; van Belkum A.; Kooistra-Smid A. M. D. Detection of Campylobacter species and Arcobacter butzleri in stool samples by use of real-time multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51 (1), 253–259. 10.1128/JCM.01716-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prouzet-Mauléon V.; Labadi L.; Bouges N.; Ménard A.; Mégraud F. Arcobacter butzleri: underestimated enteropathogen. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12 (2), 307–309. 10.3201/eid1202.050570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg O.; Dediste A.; Houf K.; Ibekwem S.; Souayah H.; Cadranel S.; Douat N.; Zissis G.; Butzler J.-P.; Vandamme P. Arcobacter species in humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10 (10), 1863–1867. 10.3201/eid1010.040241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado L.; Gutiérrez M.; González M.; Fernández H. Assessment of the prevalence and diversity of emergent campylobacteria in human stool samples using a combination of traditional and molecular methods. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 75 (4), 434–436. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atabay H. I.; Unver A.; Sahin M.; Otlu S.; Elmali M.; Yaman H. Isolation of various Arcobacter species from domestic geese (Anser anser). Vet. Microbiol. 2008, 128 (3–4), 400–405. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado L.; Guarro J.; Figueras M. J. Prevalence of Arcobacter in meat and shellfish. J. Food Prot 2009, 72 (5), 1102–1106. 10.4315/0362-028X-72.5.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González A.; Botella S.; Montes R. M.; Moreno Y.; Ferrús M. A. Direct detection and identification of Arcobacter species by multiplex PCR in chicken and wastewater samples from Spain. J. Food Prot. 2007, 70 (2), 341–347. 10.4315/0362-028X-70.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houf K.; De Smet S.; Baré J.; Daminet S. Dogs as carriers of the emerging pathogen Arcobacter. Vet. Microbiol. 2008, 130 (1–2), 208–213. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shange N.; Gouws P.; Hoffman L. C. Campylobacter and Arcobacter species in food-producing animals: prevalence at primary production and during slaughter. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35 (9), 146. 10.1007/s11274-019-2722-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi A.; Capozzi L.; Bianco A.; Caruso M.; Latorre L.; Costa A.; Giannico A.; Ridolfi D.; Bulzacchelli C.; Santagada G.. Identification of virulence and antibiotic resistance factors in Arcobacter butzleri isolated from bovine milk by whole genome sequencing. Ital. J. Food Safety 2019, 8 (2), 10.4081/ijfs.2019.7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mottola A.; Bonerba E.; Bozzo G.; Marchetti P.; Celano G. V.; Colao V.; Terio V.; Tantillo G.; Figueras M. J.; Di Pinto A. Occurrence of emerging food-borne pathogenic Arcobacter spp. isolated from pre-cut (ready-to-eat) vegetables. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 236, 33–37. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Q.; Huang Y.; Wang H.; Fang T. Diversity and abundance of bacterial pathogens in urban rivers impacted by domestic sewage. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 249, 24–35. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.02.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J. C.; Levican A.; Figueras M. J.; McLellan S. L.. Population dynamics and ecology of Arcobacter in sewage. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 525. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lu S.; Zhang X.-X.; Wang Z.; Huang K.; Wang Y.; Liang W.; Tan Y.; Liu B.; Tang J. Bacterial pathogens and community composition in advanced sewage treatment systems revealed by metagenomics analysis based on high-throughput sequencing. PLoS One 2015, 10 (5), e0125549 10.1371/journal.pone.0125549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan S. L.; Huse S. M.; Mueller-Spitz S. R.; Andreishcheva E. N.; Sogin M. L. Diversity and population structure of sewage-derived microorganisms in wastewater treatment plant influent. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12 (2), 378–392. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks O. C.; Newton R. J.; Kelty C. A.; Huse S. M.; Sogin M. L.; McLellan S. L. Comparison of the microbial community structures of untreated wastewaters from different geographic locales. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79 (9), 2906–2913. 10.1128/AEM.03448-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Cheng Y.; Qian C.; Lu W. Bacterial community evolution along full-scale municipal wastewater treatment processes. J. Water Health 2020, 18 (5), 665–680. 10.2166/wh.2020.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong T.-T.; Mansfield L. S.; Wilson D. L.; Schwab D. J.; Molloy S. L.; Rose J. B. Massive microbiological groundwater contamination associated with a waterborne outbreak in Lake Erie, South Bass Island, Ohio. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115 (6), 856–864. 10.1289/ehp.9430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Agidi S.; Marion J. W.; Lee J. Arcobacter in Lake Erie beach waters: an emerging gastrointestinal pathogen linked with human-associated fecal contamination. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78 (16), 5511–5519. 10.1128/AEM.08009-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb A. L.; Taboada E. N.; Selinger L. B.; Boras V. F.; Inglis G. D. Prevalence and diversity of waterborne Arcobacter butzleri in southwestern Alberta, Canada. Can. J. Microbiol. 2017, 63 (4), 330–340. 10.1139/cjm-2016-0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banting G. S.; Braithwaite S.; Scott C.; Kim J.; Jeon B.; Ashbolt N.; Ruecker N.; Tymensen L.; Charest J.; Pintar K.; Checkley S.; Neumann N. F. Evaluation of various Campylobacter-specific quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays for detection and enumeration of Campylobacteraceae in irrigation water and wastewater via a miniaturized most-probable-number–qPCR assay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82 (15), 4743–4756. 10.1128/AEM.00077-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado L.; Inza I.; Guarro J.; Figueras M. J. Presence of Arcobacter spp. in environmental waters correlates with high levels of fecal pollution. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10 (6), 1635–1640. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney R. L.; Labbate M.; Siboni N.; Tagg K. A.; Mitrovic S. M.; Seymour J. R. Urban beaches are environmental hotspots for antibiotic resistance following rainfall. Water Res. 2019, 167, 115081 10.1016/j.watres.2019.115081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney R. L.; Brown M. V.; Siboni N.; Raina J.-B.; Kahlke T.; Mitrovic S. M.; Seymour J. R. Highly heterogeneous temporal dynamics in the abundance and diversity of the emerging pathogens Arcobacter at an urban beach. Water Res. 2020, 171, 115405 10.1016/j.watres.2019.115405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams N. L. R.; Siboni N.; Potts J.; Campey M.; Johnson C.; Rao S.; Bramucci A.; Scanes P.; Seymour J. R. Molecular microbiological approaches reduce ambiguity about the sources of faecal pollution and identify microbial hazards within an urbanised coastal environment. Water Res. 2022, 218, 118534 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedermeyer J. A.; Miller W. G.; Yee E.; Harris A.; Emanuel R. E.; Jass T.; Nelson N.; Kathariou S. Search for Campylobacter spp. reveals high prevalence and pronounced genetic diversity of Arcobacter butzleri in floodwater samples associated with Hurricane Florence in North Carolina, USA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86 (20), e01118–20 10.1128/AEM.01118-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldgaard J.; Jørgensen K.; Ingmer H. Growth and survival at chiller temperatures of Arcobacter butzleri. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 131 (2–3), 256–259. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M.; Zhang Q.; Segawa T.; Maeda M.; Hirano R.; Okabe S.; Ishii S. Temporal dynamics of Campylobacter and Arcobacter in a freshwater lake that receives fecal inputs from migratory geese. Water Res. 2022, 217, 118397 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell R. L.; Kase J. A.; Harrison L. M.; Balan K. V.; Babu U.; Chen Y.; Macarisin D.; Kwon H. J.; Zheng J.; Stevens E. L.; Meng J.; Brown E. W. The persistence of bacterial pathogens in surface water and its impact on global food safety. Pathogens 2021, 10 (11), 1391. 10.3390/pathogens10111391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deer D. M.; Lampel K. A.; González-Escalona N. A versatile internal control for use as DNA in real-time PCR and as RNA in real-time reverse transcription PCR assays. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 50 (4), 366–372. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). Method 1611: Enterococci in water by TaqMan quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay (EPA-821-R-12–008). 2012, https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-08/documents/method_1611_2012.pdf.

- Chui L.; Lee M.-C.; Allen R.; Bryks A.; Haines L.; Boras V. Comparison between ImmunoCard STAT! and real-time PCR as screening tools for both O157:H7 and non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in southern Alberta, Canada. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 77 (1), 8–13. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke M. I.; Morton V. K.; McLellan N. L.; Huck P. M. The occurrence of Campylobacter in river water and waterfowl within a watershed in southern Ontario, Canada. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 109 (3), 1053–1066. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daum L. T.; Barnes W. J.; McAvin J. C.; Neidert M. S.; Cooper L. A.; Huff W. B.; Gaul L.; Riggins W. S.; Morris S.; Salmen A.; Lohman K. L. Real-time PCR detection of Salmonella in suspect foods from a gastroenteritis outbreak in Kerr County, Texas. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40 (8), 3050–3052. 10.1128/JCM.40.8.3050-3052.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugland R. A.; Varma M.; Sivaganesan M.; Kelty C.; Peed L.; Shanks O. C. Evaluation of genetic markers from the 16S rRNA gene V2 region for use in quantitative detection of selected Bacteroidales species and human fecal waste by qPCR. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 33 (6), 348–357. 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks O. C.; Kelty C. A.; Sivaganesan M.; Varma M.; Haugland R. A. Quantitative PCR for genetic markers of human fecal pollution. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75 (17), 5507–5513. 10.1128/AEM.00305-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green H. C.; White K. M.; Kelty C. A.; Shanks O. C. Development of rapid canine fecal source identification PCR-based assays. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48 (19), 11453–11461. 10.1021/es502637b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Marion J. W.; Lee J. Development and application of a quantitative PCR assay targeting Catellicoccus marimammalium for assessing gull-associated fecal contamination at Lake Erie beaches. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 454–455, 1–8. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremaux B.; Boa T.; Yost C. K. Quantitative real-time PCR assays for sensitive detection of Canada goose-specific fecal pollution in water sources. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76 (14), 4886–4889. 10.1128/AEM.00110-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieszkin S.; Yala J.-F.; Joubrel R.; Gourmelon M. Phylogenetic analysis of Bacteroidales 16S rRNA gene sequences from human and animal effluents and assessment of ruminant faecal pollution by real-time PCR. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 108 (3), 974–984. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti R.; Zhang Y.; Lapen D. R.; Topp E. Development and validation of a microbial source tracking marker for the detection of fecal pollution by muskrats. J. Microbiol. Methods 2011, 87 (1), 82–88. 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugland R. A.; Siefring S. C.; Wymer L. J.; Brenner K. P.; Dufour A. P. Comparison of Enterococcus measurements in freshwater at two recreational beaches by quantitative polymerase chain reaction and membrane filter culture analysis. Water Res. 2005, 39 (4), 559–568. 10.1016/j.watres.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houf K.; De Zutter L.; Van Hoof J.; Vandamme P. Assessment of the genetic diversity among arcobacters isolated from poultry products by using two PCR-based typing methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68 (5), 2172–2178. 10.1128/AEM.68.5.2172-2178.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douidah L.; De Zutter L.; Baré J.; De Vos P.; Vandamme P.; Vandenberg O.; Van Den Abeele A.-M.; Houf K. Occurrence of putative virulence genes in Arcobacter species isolated from humans and animals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50 (3), 735–741. 10.1128/JCM.05872-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilrich C.; Wilrich P.-T. Estimation of the POD function and the LOD of a qualitative microbiological measurement method. J. AOAC Int. 2009, 92 (6), 1763–1772. 10.1093/jaoac/92.6.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchardt M. A.; Boehm A. B.; Salit Marc.; Spencer S. K.; Wigginton K. R.; Noble R. T. The environmental microbiology minimum information (EMMI) guidelines: qPCR and dPCR quality and reporting for environmental microbiology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55 (15), 10210–10223. 10.1021/acs.est.1c01767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banting G.; Figueras Salvat M. J.. Arcobacter. In Water and Sanitation for the 21st Century: Health and Microbiological Aspects of Excreta and Wastewater Management (Global Water Pathogen Project); Rose J. B.; Jiménez Cisneros B.; UNESCO - International Hydrological Programme, Eds.; Michigan State University, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Engberg J.; On S. L. W.; Harrington C. S.; Gerner-Smidt P. Prevalence of Campylobacter, Arcobacter, Helicobacter, and Sutterella spp. in human fecal samples as estimated by a reevaluation of isolation methods for campylobacters. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38 (1), 286–291. 10.1128/JCM.38.1.286-291.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueras M. J.; Levican A.; Pujol I.; Ballester F.; Rabada Quilez M. J.; Gomez-Bertomeu F. A severe case of persistent diarrhoea associated with Arcobacter cryaerophilus but attributed to Campylobacter Sp. and a review of the clinical incidence of Arcobacter spp. New Microbes New Infect. 2014, 2 (2), 31–37. 10.1002/2052-2975.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W.; Hamilton K.; Toze S.; Cook S.; Page D. A review on microbial contaminants in stormwater runoff and outfalls: potential health risks and mitigation strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 692, 1304–1321. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachad M.; Lanoue M.; Vo Duy S.; Villlemur R.; Sauvé S.; Prévost M.; Dorner S. Locating illicit discharges in storm sewers in urban areas using multi-parameter source tracking: field validation of a toolbox composite index to prioritize high risk areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 152060 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart J. D.; Blackwood A. D.; Noble R. T. Examining coastal dynamics and recreational water quality by quantifying multiple sewage specific markers in a North Carolina estuary. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 747, 141124 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis S.; Spencer S.; Firnstahl A.; Stokdyk J.; Borchardt M.; McCarthy D. T.; Murphy H. M. Human Bacteroides and total coliforms as indicators of recent combined sewer overflows and rain events in urban creeks. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 630, 967–976. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nshimyimana J. P.; Ekklesia E.; Shanahan P.; Chua L. H. C.; Thompson J. R. Distribution and abundance of human-specific Bacteroides and relation to traditional indicators in an urban tropical catchment. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 116 (5), 1369–1383. 10.1111/jam.12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales-Ortells H.; Medema G. Microbial health risks associated with exposure to stormwater in a water plaza. Water Res. 2015, 74, 34–46. 10.1016/j.watres.2015.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer E. P.; VandeWalle J. L.; Bootsma M. J.; McLellan S. L. Detection of the human specific Bacteroides genetic marker provides evidence of widespread sewage contamination of stormwater in the urban environment. Water Res. 2011, 45 (14), 4081–4091. 10.1016/j.watres.2011.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley Z. R.; Boyd R. J.; Shum P.; Edge T. A. Microbial source tracking using quantitative and digital PCR to identify sources of fecal contamination in stormwater, river water, and beach water in a Great Lakes area of concern. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84 (20), e01634–18 10.1128/AEM.01634-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele J. A.; Blackwood A. D.; Griffith J. F.; Noble R. T.; Schiff K. C. Quantification of pathogens and markers of fecal contamination during storm events along popular surfing beaches in San Diego, California. Water Res. 2018, 136, 137–149. 10.1016/j.watres.2018.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaju Shrestha R.; Sherchan S. P.; Kitajima M.; Tanaka Y.; Gerba C. P.; Haramoto E. Reduction of Arcobacter at two conventional wastewater treatment plants in southern Arizona, USA. Pathogens 2019, 8 (4), 175. 10.3390/pathogens8040175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb A. L.; Taboada E. N.; Selinger L. B.; Boras V. F.; Inglis G. D. Efficacy of wastewater treatment on Arcobacter butzleri density and strain diversity. Water Res. 2016, 105, 291–296. 10.1016/j.watres.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez D.; Keeling D.; Thompson H.; Larson A.; Denby J.; Curtis K.; Yetka K.; Rondini M.; Yeargan E.; Egerton T.; Barker D.; Gonzalez R. Collection system investigation microbial source tracking (CSI-MST): applying molecular markers to identify sewer infrastructure failures. J. Microbiol. Methods 2020, 178, 106068 10.1016/j.mimet.2020.106068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer R. E.; Reischer G. H.; Ixenmaier S. K.; Derx J.; Blaschke A. P.; Ebdon J. E.; Linke R.; Egle L.; Ahmed W.; Blanch A. R.; Byamukama D.; Savill M.; Mushi D.; Cristóbal H. A.; Edge T. A.; Schade M. A.; Aslan A.; Brooks Y. M.; Sommer R.; Masago Y.; Sato M. I.; Taylor H. D.; Rose J. B.; Wuertz S.; Shanks O. C.; Piringer H.; Mach R. L.; Savio D.; Zessner M.; Farnleitner A. H. Global distribution of human-associated fecal genetic markers in reference samples from six continents. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52 (9), 5076–5084. 10.1021/acs.est.7b04438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W.; Toze S.; Veal C.; Fisher P.; Zhang Q.; Zhu Z.; Staley C.; Sadowsky M. J. Comparative decay of culturable faecal indicator bacteria, microbial source tracking marker genes, and enteric pathogens in laboratory microcosms that mimic a sub-tropical environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141475 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W.; Payyappat S.; Cassidy M.; Harrison N.; Besley C. Sewage-associated marker genes illustrate the impact of wet weather overflows and dry weather leakage in urban estuarine waters of Sydney, Australia. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135390 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fera M. T.; La Camera E.; Carbone M.; Malara D.; Pennisi M. G. Pet cats as carriers of Arcobacter spp. in southern Italy. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 106 (5), 1661–1666. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.04133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Man H.; Van Den Berg H. H. J. L.; Leenen E. J. T. M.; Schijven J. F.; Schets F. M.; Van Der Vliet J. C.; Van Knapen F.; De Roda Husman A. M. Quantitative assessment of infection risk from exposure to waterborne pathogens in urban floodwater. Water Res. 2014, 48, 90–99. 10.1016/j.watres.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy H. M.; Meng Z.; Henry R.; Deletic A.; McCarthy D. T. Current stormwater harvesting guidelines are inadequate for mitigating risk from Campylobacter during nonpotable reuse activities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51 (21), 12498–12507. 10.1021/acs.est.7b03089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petterson S. R.; Mitchell V. G.; Davies C. M.; O’Connor J.; Kaucner C.; Roser D.; Ashbolt N. Evaluation of three full-scale stormwater treatment systems with respect to water yield, pathogen removal efficacy and human health risk from faecal pathogens. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 543, 691–702. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoen M. E.; Ashbolt N. J.; Jahne M. A.; Garland J. Risk-based enteric pathogen reduction targets for non-potable and direct potable use of roof runoff, stormwater, and greywater. Microb. Risk Anal. 2017, 5, 32–43. 10.1016/j.mran.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schriewer A.; Miller W. A.; Byrne B. A.; Miller M. A.; Oates S.; Conrad P. A.; Hardin D.; Yang H.-H.; Chouicha N.; Melli A.; Jessup D.; Dominik C.; Wuertz S. Presence of Bacteroidales as a predictor of pathogens in surface waters of the central California coast. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76 (17), 5802–5814. 10.1128/AEM.00635-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musmanno R. A.; Russi M.; Lior H.; Figura N. In vitro virulence factors of Arcobacter butzleri strains isolated from superficial water samples. Microbiologica 1997, 20, 63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.