Abstract

A 1-year-old, female spayed domestic shorthair cat was presented with a 4-week history of dysphagia and regurgitation soon after oral treatment with clindamycin. Fluoroscopic and endoscopic examinations confirmed the presence of a single cervical oesophageal stricture 4 cm caudal to the pharynx. A fluoroscopically and endoscopically guided balloon dilation was performed six times consecutively over a period of 3 weeks as reformation of the stricture appeared within 3–7 days. Feeding via percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy-tube as long-term management of the condition was declined by the owner. A self-expanding metal oesophageal stent with the following dimension was subsequently implanted: fully open diameter 16 mm, length 30 mm. After stent implantation, the cat was fed on mashed canned food and did not show any clinical signs for 12 months. Twelve months post-implantation the cat was no longer able to eat even liquid food, became lethargic and the owner opted for euthanasia. On post-mortem examination the stent surfaces were overgrown by oesophageal mucosa by approximately 50%. Stent obstruction was detected and caused by swallowed hair which also seemed to have hampered mucosal integration in the distal part of the stent.

Oesophageal strictures occur secondary to deep oesophageal inflammation and result in regurgitation and other signs such as dysphagia. The most common causes of oesophagitis include gastric reflux under general anaesthesia, vomiting, foreign bodies and ingestion of caustic agents (Sellon and Willard 2003). Strictures usually result from granulation and scar tissue formation following ulceration caused by damage to the oesophageal mucosa. In cats, oesophageal strictures have also been reported as a complication of doxycycline and clindamycin therapy (Melendez et al 2000, Leib et al 2001, McGrotty and Knottenbelt 2002, German et al 2005, Beatty et al 2006). The most commonly used therapy for oesophageal strictures in veterinary medicine is balloon dilation. Retrospective studies of dogs and cats that have undergone dilation procedures have shown a median of two to three dilation procedures needed per patient, with ranges varying from one to more than eight attempts to dilate the stricture (Harai et al 1995, Melendez et al 1998, Leib et al 2001, Adamama-Moraitou et al 2002). Extreme cases may require 12–20 attempts.

Although balloon dilation in a single stricture is successful in up to 80% of patients, reformation of stricture is a complication which can occur also after several consecutive balloon dilations. In such cases percutaneous gastric tube feeding would be the long-term management, although this is often declined by the owners due to the extensive maintenance requirement.

A 1-year-old, female spayed domestic shorthair cat was presented with a 4-week history of dysphagia and regurgitation. Six weeks prior to presentation the cat had been treated for a suspected uveitis with clindamycin hydrochloride (Cleorobe; Pfizer, 12.5 mg/kg every 12 h) by the referring veterinary surgeon. No major abnormalities were detected on physical examination, routine haematology and serum biochemistry. The cat tested negative for feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) (Snap FIV/FeLV test; Idexx). Thoracic and abdominal radiographs were unremarkable. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed under general anaesthesia but neither a 9 mm nor a 5 mm diameter endoscope could be passed more than 6 cm from the incisor of the upper jaw into the oesophagus. A fluoroscopic swallow study with liquid iodine contrast agent (Ultravist 300; Schering, Berlin) confirmed the presence of a single cervical oesophageal stricture (initial diameter 1 mm) 6 cm caudal to the incisor of the upper jaw, at the level of the thoracic inlet (Fig 1). Balloon dilation of the oesophageal stricture (5 F, 4 mm, 8 bar, balloon dilation catheter, PTCA catheter with LFC hydrophilic coating, Alivante; Italy) was performed using fluoroscopic guidance. The balloon was positioned centrally over the stricture and the balloon was inflated for 30 s. The procedure was repeated 2 days later initially with the same balloon catheter and subsequently with a 6.5 mm diameter balloon catheter (3.5 F, 6.5 mm, 8 bar, balloon dilation catheter, PTCA catheter with LFC hydrophilic coating, Alivante; Italy). Some mucosal tears and a mild haemorrhage could be seen endoscopically at the dilation site each time. After the second dilation procedure the area of the stricture could be passed by a 9 mm endoscope. Complete oesophagoscopy was performed and no further strictures were detected. Management after dilation included feeding a mashed diet, buprenorphine (0.01 mg/kg bid, intravenously, Temgesic; Essex), prednisolone (1 mg/kg sid, per os, Prednisolone; cp-pharma, Burgdorf, Germany), amoxycillin–clavulanic acid (20 mg/kg bid, per os, Synulox; Pfizer), ranitidine (2 mg/kg bid, per os, Zantic; GSK OTC Medicines) and sucralfate (1 ml tid, per os, Ulcogant; Merck). The cat was eating well and showed no regurgitation for 7 days but then started to regurgitate again. Endoscopy confirmed reformation of the stricture. A fluoroscopically and endoscopically guided balloon dilation (diameter of the balloon each time was 10 mm) was performed four times over a period of 3 weeks but stricture reformation always recurred within 3–7 days. Medical treatment was continued as described previously. After six dilations the owner declined further procedures despite being informed that the prognosis is not correlated to the number of dilations. Feeding via percutaneous gastric tube as long-term management was also declined by the owner.

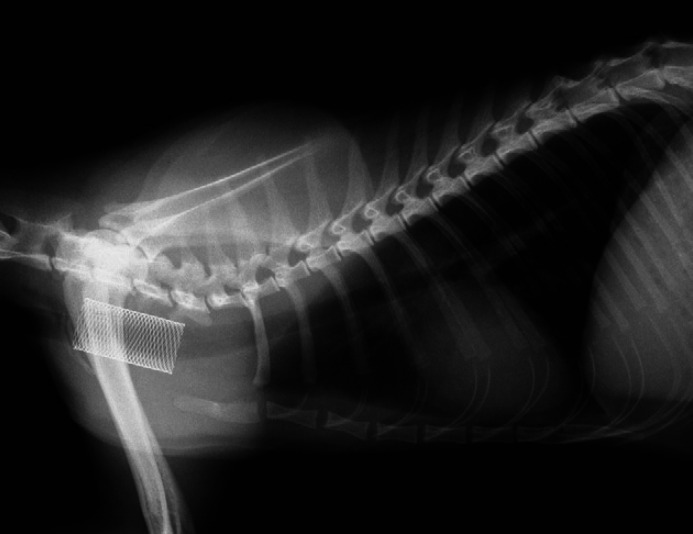

Fig 1.

Fluoroscopic swallow study with liquid iodine contrast agent showed the presence of a single cervical oesophageal stricture.

A self-expanding metal stent (fully open diameter 16 mm, length 30 mm; Boston Scientific, Zuchwil, Switzerland) was subsequently implanted. Prior to stent placement the stricture was dilated using balloons of 6 and 10 mm diameter. The stent was passed into the stricture under direct endoscope guidance and released under fluoroscopic control (Fig 2). The day after stent implantation the cat ate a mashed canned diet and was treated for 5 days with buprenorphine (0.01 mg/kg sid, intravenously, Temgesic; Essex) and enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg sid, subcutaneously, Baytril; Bayer). On re-examination 5 weeks later no signs of dysphagia or regurgitation were reported and a normal canned diet mixed with water was being fed. At this time fluoroscopy revealed no oesophageal motility cranial to the stent, but the oesophagus showed normal motility caudal to the stent. On endoscopy the stent appeared to be completely overgrown by mucosa. A telephone follow-up 5 months later revealed no further signs of dysphagia or regurgitation on mashed canned cat food.

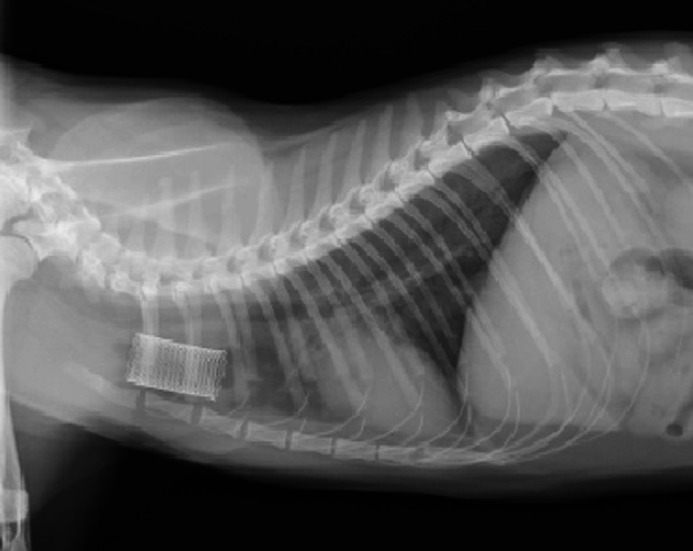

Fig 2.

Latero-lateral thoracic radiograph post-stent implantation.

Ten months post-stent implantation the cat behaved normally and did not show any regurgitation when fed a mashed canned diet from a higher position. However, feeding other diets or not from a higher position resulted in regurgitation. On thoracic radiographs the oesophageal stent was located more ventrally and caudally compared to initial radiographs taken directly after implantation (Fig 3). Fluoroscopic examination revealed a diverticulum located directly caudal to the stent. Complete oesophagoscopy with a 9 mm-endoscope was no longer possible, the oesophagus could not be passed by the endoscope at the level of the stent. A smaller diameter endoscope was not tried. Twelve months post-implantation the cat was no longer able to eat even liquid food, became lethargic and the owner opted for euthanasia. On post-mortem examination the stent surfaces were overgrown by oesophageal mucosa by approximately 50%. Stent obstruction was detected and caused by swallowed hair that also seemed to have hampered mucosal integration in the distal part of the stent (Fig 4). Directly caudal to the stent a diverticulum was seen. Histopathological examination revealed mild neutrophilic inflammation in this area, while the remaining oesophagus was unremarkable. Pressure necrosis and/or fistula formation were not present.

Fig 3.

Thoracic radiograph taken 10 months post-stent implantation showed the oesophageal stent located more ventrally and caudally at the level of first to third ribs.

Fig 4.

Post-mortem examination of oesophagus detected stent obstruction caused by swallowed hair that also seemed to have hampered mucosal integration in the distal part of the stent.

Drug-induced oesophageal disorders are commonly diagnosed in humans. More than 70 drugs are known to cause oesophagitis and antibiotics are implicated in over 50% of cases (Jaspersen 2000). Doxycycline, clindamycin and trimethoprim–sulphonamide are most commonly implicated (Boyce 1998, Rivera Vaquerizo et al 2004). A history of taking medications with an inadequate volume of liquid immediately before becoming recumbent is typical. The incidence of drug-induced oesophageal disorders in companion animals is unknown, but there have been several case reports of suspected doxycycline or clindamycin-induced oesophageal stricture formation in cats (Melendez et al 2000, Leib et al 2001, McGrotty and Knottenbelt 2002, Beatty et al 2006). The oesophageal injuries reported in these cases most likely resulted from the administration of tablets or capsules by dry swallow. Prolonged oesophageal contact in combination with a direct injurious effect on the oesophageal mucosa is important; parenteral medications do not cause oesophageal injury. Westfall et al (2001) documented that tablets and capsules have longer oesophageal transit time in cats after dry swallows when compared to wet swallows. The study also showed that capsules given to cats by dry swallow were retained in the cervical oesophagus (88%) or oropharynx (8%). According to the history, the oesophageal stricture in our case most likely resulted from the administration of clindamycin by dry swallow.

The goal of treating oesophageal strictures is to resolve regurgitation and maintain nutrition and hydration by oral feeding. To do this dilation of the oesophageal stricture is necessary, either by balloon or by bougienage. The main difference between both methods lies in the force generated during the dilation procedure. Balloon dilation exerts primarily radial forces, whereas bougienage exerts shear forces next to radial forces (McLean and LeVeen 1989).

Retrospective studies of dogs and cats that have undergone balloon dilation procedures have shown a median of two to three dilation procedures needed per patient, with ranges varying from one to more than eight attempts to dilate the stricture (Harai et al 1995, Melendez et al 1998, Leib et al 2001, Adamama-Moraitou et al 2002, Linden and Kohn 2003). Even though the owner was aware that multiple dilation procedures might be needed he was not willing to continue when clinical signs recurred after the sixth dilation procedure. Feeding via percutaneous gastric tube as long-term management of the condition was declined. Therefore, an oesophageal stent implantation was offered. Before performing the procedure the owner was informed about possible risks, complications and the fact that there have been limited attempts at using such devices in dogs and cats, with suggestions of a high complication rate (Gualtieri 2001). In people, metallic self-expanding oesophageal stents are widely used, with good success rates, for the treatment of malignant oesophageal strictures (Song et al 1994) and malignant tracheo-oesophageal fistulas (Bethge et al 1995). There are far fewer reports of their use in the treatment of benign conditions, and only few of them have been used with some short-term success (Cordero and Morres 2000). Although some patients have returned to function after stenting, the use of a stent carries its own set of complications (Cordero and Morres 2000, Ackroyd et al 2001). The stents can migrate from the placement site and require removal, but removal can prove difficult because of the inflammatory response provoked by the presence of the stent. Pressure necrosis at the ends of the stent can lead to tracheo-oesophageal or broncho-oesophageal fistulas. This may be especially true in dogs and cats if the stent is placed near the thoracic inlet such that one end of the stent is near the site where the oesophagus goes from being horizontal to somewhat more vertical and constant neck movement causes the oesophageal mucosa to constantly rub against the end of the stent. The stent itself also can become obstructed with food or other material. In our case, the cat remained asymptomatic for almost 12 months even though some oesophageal motility impairment was already detected 5 weeks post-implantation. Furthermore, the displacement of the stent did not result in clinical signs as long as the cat was fed mashed diet from a higher position. Swallowed hair being caught in the mesh network of the stent appeared to be the cause of hampered mucosal integration in the distal part of the stent. Exacerbation of this process led to complete obstruction of the stent resulting in euthanasia. Pressure necrosis or even fistula formation was not detected on post-mortem examination. Wearing a buster collar for a definitive time period might improve stent integration. Biodegradable stent systems have been used in human medicine, mainly with urological and vascular applications (Isotalo et al 2002, Uurto et al 2005). Recently, the use of biodegradable stents in benign oesophageal strictures in humans has also been described in a case series (Saito et al 2007). The principle is to use stents which gradually degrade while maintaining their dilation force. The main complication described in the case series was spontaneous migration of the stents occurring between 10 and 21 days after placement. No obstructive complication was observed and migrated stents were excreted with faeces. However, in cats the likelihood of gastrointestinal obstruction secondary to spontaneous migration would be greater given the relative size of the stent to the patient. However, even in cases with a migrated stent, the fact that reformation of the initial stricture was not reported for up to 2 years post-intervention is promising.

References

- Ackroyd R., Watson D.I., Devitt P.G., Jamieson G.G. Expandable metallic stents should not be used in the treatment of benign esophageal strictures, Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 16, 2001, 484–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamama-Moraitou K.K., Rallis T.S., Prassinos N.N., Galatos A.D. Benign esophageal stricture in the dog and cat: a retrospective study of 20 cases, Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research 66, 2002, 55–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty J.A., Swift N., Foster D.J., Barrs V. Suspected clindamycin-associated oesophageal injury in cats: five cases, Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 8, 2006, 412–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethge N., Sommer A., Vakil N. Treatment of oesophageal fistulas with a new polyurethane-covered, self-expanding mesh stent: a prospective study, American Journal of Gastroenterology 90, 1995, 2143–2146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce H.W. Drug-induced esophageal damage: diseases of medical progress, Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 47, 1998, 547–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero J.A., Jr., Morres D.W. Self-expanding esophageal metallic stents in the treatment of esophageal obstruction, The American Surgeon 66, 2000, 956–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German A.J., Cannon M.J., Dye C., Booth M.J., Pearson G.R., Reay C.A., Gruffydd-Jones T.J. Oesophageal strictures in cats associated with doxycycline therapy, Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 7, 2005, 33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri M. Esophagoscopy, Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice 31, 2001, 605–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harai B.H., Johnson S.E., Sherding R.G. Endoscopically guided balloon dilation of benign esophageal strictures in 6 cats and 7 dogs, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 9, 1995, 332–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isotalo T., Talja M., Välimaa T., Törmälä P., Tammela T.L. A bioabsorbable self-expandable, self-reinforced poly-l-lactic acid urethral stent for recurrent urethral strictures: long-term results, Journal of Endourology 16, 2002, 759–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspersen D. Drug-induced oesophageal disorders: pathogenesis, incidence, prevention and management, Drug Safety: An International Journal of Medical Toxicology and Drug Experience 22, 2000, 237–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leib M.S., Dinnel H., Ward D.L., Reimer M.E., Towell T.L., Monroe W.E. Endoscopic balloon dilation of benign esophageal strictures in dogs and cats, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 3, 2001, 139–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden T., Kohn B. Literature review of oesophageal strictures with demonstration of a balloon dilation in two dogs and one cat, Kleintierpraxis 48, 2003, 237–241. [Google Scholar]

- McGrotty Y.L., Knottenbelt C.M. Oesophageal stricture in a cat due to oral administration of tetracyclines, Journal of Small Animal Practice 43, 2002, 221–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean G.K., LeVeen R.F. Shear stress in the performance of esophageal dilation: comparison of balloon dilation and bougienage, Radiology 172, 1989, 983–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez L., Twedt D.C., Weyrauch E.A., Willard M.D. Conservative therapy using balloon dilation for intramural, inflammatory esophageal strictures in dogs and cats: a retrospective study of 23 cases (1987–1997), European Journal of Comparative Gastroenterology 3, 1998, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Melendez L., Twedt D., Wright M. Suspected doxycycline-induced esophagitis with esophageal stricture formation in three cats, Feline Practice 28, 2000, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Vaquerizo P.A. Rivera, Lopez Y. Santisteban, Colmenarejo M. Blasco, Gutierrez M. Vicente, Garcia V. Garcia, Perez-Flores R. Clindamycin-induced esophageal ulcer, Revista Espanola de Enfermedades Digestivas 96, 2004, 143–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y., Tanaka T., Andoh A., Minematsu H., Hata K., Tsujikawa T., Nitta N., Murata K., Fujiyama Y. Novel biodegradable stents for benign esophageal strictures following endoscopic submucosal dissection, Digestive Diseases and Sciences 53, 2007, 330–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellon K.R., Willard M.D. Esophagitis and esophageal strictures, Veterinary Clinics of North America 33, 2003, 945–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H.Y., Do Y.S., Han Y.M. Covered expandable esophageal metallic stent tubes: experiences in 119 patients, Radiology 193, 1994, 689–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uurto I., Mikkonen J., Parkkinen J., et al. Drug-eluting biodegradable poly-d/l-lactic acid vascular stents: an experimental pilot study, Journal of Endovascular Therapy 12, 2005, 371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall D.S., Twedt D.C., Steyn P.F., Oberhauser E.B., VanCleave J.W. Evaluation of esophageal transit of tablets and capsules in 30 cats, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 15, 2001, 467–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]