Tighter controls on the way that GPs practise are certain to follow the conviction this week of Dr Harold Shipman, the most prolific serial killer in British criminal history. The health secretary, Alan Milburn, announced an inquiry into failures in the system that allowed the 54 year old doctor to murder his patients at will.

The Greater Manchester family doctor will die in prison after receiving 15 life sentences for murdering 15 of his middle aged and elderly women patients by lethal injections of diamorphine.

Police have sent dossiers on a further 23 deaths to the Crown Prosecution Service and believe he may have killed as many as 150 patients during his 30 year career.

His motive for wreaking mass murder on his patients was as mysterious at the end of the lengthy trial as it was at the beginning. The prosecution postulated that he enjoyed exercising the ultimate power of life and death.

Dr Shipman stood to gain financially from only one of the deaths, that of 81 year old Kathleen Grundy. It was his clumsy attempt to forge her will, making himself the sole beneficiary of her £386000 ($617000) estate, that eventually led to his discovery.

Together with the Bristol children's heart surgery debacle, the Shipman case has shaken public confidence in the medical profession and is likely to lead to widespread reform.

Changes expected to follow include closer monitoring of GPs—particularly singlehanded practitioners—by health authorities; greater controls to prevent the stockpiling of drugs (Dr Shipman had enough diamorphine to kill 1500 patients); more stringent requirements on GPs who countersign other doctors' cremation certificates; and wider powers for coroners.

New duties may be placed on the General Medical Council to pass on information about doctors who come before it. West Pennine Health Authority, which covers Hyde, where Dr Shipman practised, was unaware that he had been addicted to pethidine and had a 1976 conviction for forging prescriptions for the drug. He was allowed to rehabilitate himself, and he returned to private practice after working in community health.

The GMC said that it had received no information to suggest any misuse of drugs by Dr Shipman between 1976 and his arrest in 1998. There were complaints about three separate incidents, but none suggested a fundamental problem in the GP's practice.

The GMC's president, Sir Donald Irvine, said: “We will work with NHS management and others to ensure that lessons are learned from this tragic case.” (See p 329.)

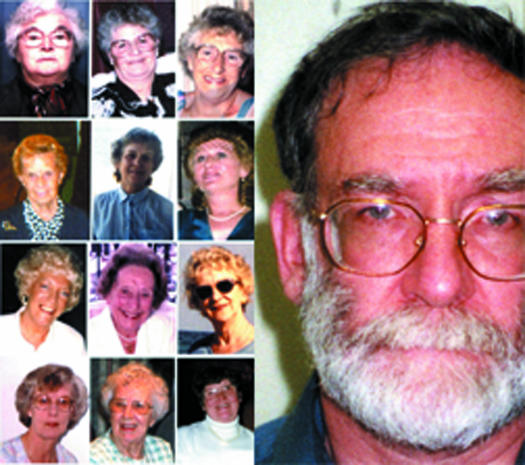

Figure.

PA

With tighter controls, would Dr Harold Shipman have been able to kill these women?