Abstract

Immune recovery uveitis (IRU) is an intraocular inflammation that typically occurs as part of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) in the eye. Typically, it affects human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients with recognized or unrecognized cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis who are receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). IRU is a common cause of new vision loss in these patients, and it manifests with a wide range of symptoms and an increased risk of inflammatory complications, such as macular edema. Recently, similar IRU-like responses have been observed in non-HIV individuals with immune reconstitution following immunosuppression of diverse etiologies, posing challenges in diagnosis and treatment. This review provides an updated overview of the current literature on the epidemiology, pathophysiology, biomarkers, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and treatment strategies for IRU.

Keywords: Cytomegalovirus retinitis, Human immunodeficiency virus, Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, Immune recovery uveitis, Uveitis

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is a retrovirus-induced multisystemic disease that results in the gradual deterioration of the immune system. HIV infection is characterized by the activation of both T and B lymphocytes, leading to the production of inflammatory cytokines. This polyclonal activation of lymphocytes results in the generation of both CD4 + and CD8 + lymphocytes [1]. Inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-2 (IL-2), interleukin-1 (IL-1), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha further stimulate HIV replication and hasten the progressive destruction of the immune system [1]. As host immune defenses become increasingly compromised, the weakened immune system predisposes infected individuals to opportunistic infections [1, 2].

The introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) marked a pivotal moment in the management of HIV infection, dramatically altering the disease course. This multifaceted approach results in a significant decrease in plasma levels of HIV mRNA and a concomitant increase in CD4 + T-lymphocyte counts, leading to an increased survival rate and a reduction in the incidence of opportunistic infections [1, 3].

In 1998, the American Journal of Ophthalmology published a group of articles that discussed the developing issue of intraocular inflammation among individuals with HIV infection [4]. In patients with CD4 + cell counts lower than 50 cells/μL, it is advised to perform regular ocular evaluations due to the multiple ocular presentations associated with HIV infection [1, 5].

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common opportunistic infection in late-stage HIV infection [6]. CMV retinitis (CMVR) is associated with a CD4 + T cell count of less than 50/μL and is caused by the dissemination of the virus through retinal blood vessels following hematogenous spread after the reactivation of latent CMV infection [6, 7]. In patients with HIV and CMVR, ocular inflammation is typically minimal or absent, which can be attributed to the underlying immunosuppressed state [8]. The diagnosis of CMVR is usually straightforward, as it presents as centripetal necrotic retinal areas with associated hemorrhage, known as “pizza retinopathy,” variable small dot-like lesions, and retinal vasculitis with perivascular sheathing [9]. CMVR causes full-thickness retinal necrosis, which leaves an atrophic scar and may result in decreased visual acuity [7, 10].

Notably, the incidence of CMVR has decreased by as much as 90% with the advent of HAART therapy [7, 11]. A response to HAART, also known as immune recovery, is defined as an increase in CD4 + T cell count of at least 50 cells/μL, with a target level of 100 cells/μL or more [12].

Although it has reduced the prevalence of opportunistic infections, HAART has also increased the incidence of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) [13, 14]. This phenomenon is characterized by the paradoxical worsening of a treated opportunistic infection or the unmasking of a previously subclinical, untreated infection in patients with HIV following the initiation of HAART due to a tissue-destructive inflammatory response [15]. The incidence of IRIS in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) receiving HAART ranges from 10 to 32% [13, 14].

The current definition of IRIS includes five criteria: (1) confirmation of HIV infection, (2) temporal association between IRIS development and HAART initiation, (3) specific host responses to HAART, such as a decrease in plasma levels of HIV RNA and an increase in CD4 + cell count, (4) clinical deterioration characterized by an inflammatory process, and (5) exclusion of other causes. Pathogens associated with IRIS include Mycobacterium tuberculosis, atypical mycobacterium, CMV, Varicella-zoster virus, Pneumocystis jirovecii, Toxoplasmosis gondii, and Cryptococcus neoformans [1, 16].

The majority of cases of IRIS occur during the first three months of HAART, although it can appear later, generally 3–12 months after HAART initiation [17]. A few cases occurring up to four years later have been described [18].

Ocular IRIS is referred to as immune recovery uveitis (IRU), which remains a leading cause of ocular morbidity [1]. IRU is the most common form of IRIS in HIV-infected patients with CMVR who are receiving HAART [1, 19]. The underlying pathogenesis of IRU is not yet fully comprehended. It is generally accepted that IRU is a response against CMV within the eye, and it is a paradoxical intraocular inflammation that occurs following CMVR [20, 21]. This immune recovery is associated with a heightened incidence of inflammatory complications, including macular edema [1].

In general, HAART is recommended to be started immediately after the diagnosis of HIV. However, a 2005 study suggested that delaying HAART may result in a reduction in the frequency and severity of CMV-associated IRU [22].

Although IRU can manifest in patients long after the initiation of HAART, it is hypothesized that incomplete CMVR resolution with subclinical production of viral proteins can persistently stimulate the immune system in some patients, leading to the development of IRU [23]. Thus, maintenance of anti-CMV therapy following the initiation of HAART may reduce the incidence and severity of IRU. However, despite anti-CMV therapy, IRU may still occur in these patients [23].

Epidemiology

IRU has been recognized as a significant contributor to vision loss in patients with CMVR related to HIV [24]. The incidence of IRU varies among studies, and this variability may be attributed to various factors, including the era of HAART therapy [13, 22, 25–27]. Studies have shown that IRU affects 10% of patients with CMVR in the early HAART era [25]. In a retrospective study, IRU was observed in 17.4% of patients receiving HAART. Of these patients, more than half developed IRU with only a minimal increase in CD4 counts of approximately 100 to 150 cells/mm3 [13]. A prospective multicenter observational study conducted in the modern HAART era revealed that the incidence of IRU was 1.7 to 2.2 per 100 person-years (PY) and was correlated with higher rates of vision loss and blindness when compared to individuals who had immune recovery without IRU [28].

Several factors may contribute to the lower incidence of IRU in some studies, including the use of more aggressive anti-CMV therapy before and after initiating potent antiretroviral therapy, which may reduce exposure to CMV antigens during the critical period of immune recovery in the eye [23]. Another contributing factor could be the use of intravitreal cidofovir, a significant risk factor for IRU that was utilized in the treatment of CMVR in older studies [26].

The decision-making process regarding the timing of HAART in the presence of CMVR is complex. Early introduction of HAART before completing induction therapy for CMV may result in a higher incidence of IRU [1, 7]. Controlling CMVR before starting HAART can significantly reduce the occurrence and severity of IRU [22]. Therefore, continuing anti-CMV treatment to minimize lesions until the immune system is strong enough to control retinitis is necessary [23]. However, it is essential to recognize the nuanced nature of this decision. IRIS develops as the immune system recovers from a low CD4 count. This underscores the importance of considering the initiation of HAART before CMVR develops to prevent a low CD4 count [1, 3].

Despite the availability of HAART, patients with HIV and CMVR remain at an increased risk for mortality, retinitis progression, complications of retinitis, and visual loss over five years [1].

Pathophysiology and biomarkers

The eye is considered an immunological sanctuary due to the blood-aqueous and blood‒retina barriers, composed of retinal microvascular endothelial cells and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), which prevent large molecules, cells, and microorganisms from entering the eye [21]. In individuals with HIV, ocular complications can occur due to the breakdown of the blood‒retinal barrier (BRB), facilitating the leakage of CMV antigens within the eye. This phenomenon may or may not be associated with viremia status in HIV patients, enabling CMV antigens to access lymphoid organs and trigger an antigen-specific immune response [1, 6]. The underlying mechanism for this breakdown is not fully understood, but exposure of retinal neurosensory and glial cells to HIV Tat, the transactivator protein of HIV-1, has been shown to result in increased activation and release of proinflammatory mediators [29]. Additionally, HIV-1 Tat protein has been found to induce apoptosis in human retinal microvascular endothelial cells and RPE cells [29].

As immune function improves with HAART, a threshold is reached at which the body can mount an intraocular inflammatory response to CMV antigens present in the eye. As immune function continues to recover, the threshold is elevated, leading to the inactivation of CMV by the immune system. This results in the cessation of CMV replication, reducing the antigen load, and subsequently, the inflammatory reactions subside [4].

Several biomarkers have been identified over the years. Immunohistological examination of epiretinal membrane (ERM) associated with IRU has shown evidence of chronic inflammation with a predominant T-lymphocyte presence, suggesting that IRU may be due to a T cell-mediated reaction to CMV antigen [30, 31]. Samples of aqueous and vitreous fluids from patients with IRU and CMVR were examined for the presence of cytokines and CMV DNA. Inflammatory IRU can be differentiated from active CMVR by the presence of IL-12 and less IL-6 and the absence of detectable CMV replication [6, 32].

Furthermore, a unique immunologic signature of cytokine-mediated inflammatory response pattern (IP-10, PDGF-AA, G-CSF, MCP-1, fractalkine, Flt-3L) is actively present in the aqueous humor [33]. Reports have suggested that all patients with clinical and ophthalmological characteristics of IRU show the presence of HLA-A2, HLA-B44, HLA-DR4, and HLA-B8-18 [12, 34]. The expression of miRNA-192 in patients with IRU was significantly decreased, which may help identify the status of people living with HIV [35].

A multicenter observational study found that patients with IRU had weaker antiviral CD4 + T cell responses than control subjects who did not develop IRU, while CD8 + T cell responses were comparable. Patients with IRU also had a smaller number of Th17 cells, which may reflect greater losses throughout the course of HIV disease and a greater level of immune dysfunction. In their opinion, CD4 cell count and Th17 cell number may both be measures of the severity of HIV disease before the initiation of HAART [36]. Three metabolites were identified as the most specific indices to distinguish IRIS before HAART: (i) oxidized cysteinyl-glycine (Cys-Gly Oxidized), (ii) 1-myristoyl-2-palmitoyl GPC (14:0/16:0), and (iii) the sulfate of piperine metabolite (C18H21NO3) [37]. However, after 1 month of HAART, quinolinate, gluconate, and serine were the indices driving the distinction [37]. These serum metabolites are specific markers for systemic IRIS and are not explicitly mentioned for uveitis [37]. However, as IRU is part of IRIS, these metabolites may also serve as biomarkers for IRU, although no previous studies have described specific metabolites for IRU. Additionally, plasma TNF-α and mucin domain 3 levels were significantly increased after HAART in HIV-infected patients with IRIS [38].

Clinical presentation

IRU is a clinical entity with variable manifestations, ranging from anterior uveitis to severe vitritis, with potential complications that can significantly impact visual function. The severity of inflammation is influenced by several factors, including the degree of immune reconstitution, the extent of CMVR, the amount of intraocular CMV antigen, and previous treatment [1].

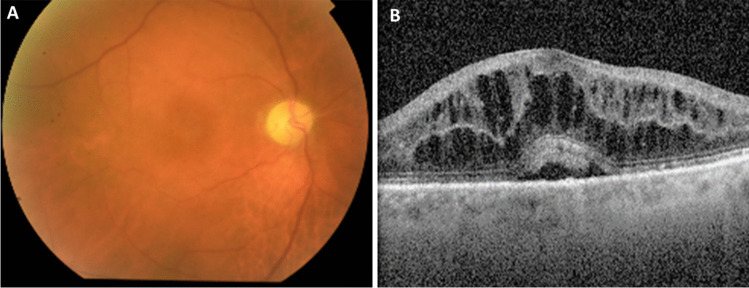

Typical symptoms of IRU include floaters and moderate visual acuity loss (usually worse than 20/40 but better than 20/200) [1]. Following initiation of HAART and increasing CD4 + lymphocyte counts, an anterior chamber inflammatory reaction and vitreous haze (Fig. 1A) may develop within weeks [5, 19]. However, this stage can be transient and easily missed [8].

Fig. 1.

Clinical presentation of IRU. A A fundoscopy with discrete vitritis, macular edema, optic disc pallor and peripheral atrophic chorioretinal scars with no signs of activity of CMVR in one 71-year-old patient with microscopic polyangiitis treated with mycophenolate mofetil referred for observation due to complaints of left reduced visual acuity and floaters that started ten months after suspension of immunosuppressive therapy due to CMV colitis. B The optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the same patient with cystoid macular edema

Mostly, patients with IRU do not have active CMVR, as the improved immune function that leads to inflammation also enables better control of the CMVR. In some cases, the infection may remain clinically inactive even without specific anti-CMV therapy [39].

Complications associated with IRU include cystoid macular edema (CME) (Fig. 1B), which is the leading cause of vision loss in patients with IRU [1]. A study found that patients with IRU had a 20-fold higher risk of CME than those without IRU [25]. Other potential clinical manifestations or complications of IRU include anterior segment inflammation, synechiaes, cataracts, vitreomacular traction, ERM formation, macular hole, proliferative vitreoretinopathy with risk of retinal detachment, frosted branch angiitis, papillitis, neovascularization of the retina or optic disc, severe postoperative inflammation, and uveitic glaucoma [1, 5, 21, 40].

The risk of IRU-induced complications is proportional to the absolute difference in CD4 + counts between the start of HAART and the development of IRU [41]. Therefore, close monitoring of CD4 + counts and regular ophthalmologic evaluations are essential for early detection and management of IRU and its associated complications.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

IRU is an exclusion diagnosis that is typically associated with HIV patients receiving HAART who have experienced an increase in their CD4 + T cell count > 100 cells/mm3 and have a new paradoxical inflammation in an eye with a preexisting history of CMVR or other ocular infection. The current definition of IRU requires the presence of intraocular inflammation that cannot be explained by drug toxicity or a new infection, for example, cidofovir toxicity, rifabutin toxicity, syphilitic uveitis, ocular tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis retinochoroiditis, and the development of new sarcoidosis [1, 9]. In certain immunocompromised patients, as the immune system undergoes recovery, an immune response may occur, giving rise to an IRU-like syndrome. Diagnostic testing, such as multimodal imaging, ocular polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and diagnostic vitrectomy, is essential in cases where the differential diagnosis includes inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic processes [42]. Furthermore, IRU-like responses have been observed in HIV-negative individuals with recovery from immunosuppression due to other etiologies, including lymphoma, Wegener granulomatosis, Good Syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, leukemia, and after renal and bone marrow transplant [42–53]. Mostly, immunosuppressive treatment reduction is associated with the manifestation of IRU-like syndromes. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of clinical cases documenting IRU in non-HIV patients from the literature.

Table 1.

IRU in non-HIV case reports

| Source | Predisposing condition | Pre-existing history of ocular infection | Occurrence of IRU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kuo, 2004 [53] | Bone marrow transplant | CMV | After lowering the imunnosupressive therapy |

| Kuo, 2004 [53] | Interstitial lung disease | CMV | After lowering the imunnosupressive therapy (cyclophosphamide) |

| Kuo, 2004 [53] | Cardiac transplant | CMV | After lowering the imunnosupressive therapy |

| Kuo, 2004[53] | Systemic necrotizing vasculitis | CMV | After lowering the imunnosupressive therapy (cyclophosphamide) |

| Miserocchi, 2005 [47] | Renal transplant | CMV | After lowering the imunnosupressive therapy (cyclosporin and prednisone) |

| Baker, 2006 [45] | Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | CMV | After tapering immunosuppression (cyclosporine and mycophenolate) to prevent graft rejection of bone marrow transplant |

| Bessho, 2007 [46] | Wegener's granulomatosis | CMV | After lowering the immunosuppressive therapy (cyclophosphamide and prednisone) |

| Wimmersberger, 2011 [51] | Chronic lymphatic leukaemia | CMV | After chemotherapy cessation |

| Agarwal, 2014 [52] | Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia | CMV | After lowering the imunnosupressive therapy |

| Agarwal, 2014 [52] | Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia | CMV | After lowering the imunnosupressive therapy |

| Agarwal, 2014 [52] | Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia | CMV | After lowering the imunnosupressive therapy |

| Agarwal, 2014 [52] | Renal transplant | CMV | After lowering the imunnosupressive therapy |

| Downes, 2016 [50] | Good syndrome | CMV | During anti-CMV therapy |

| Yanagisawa, 2017 [49] | Rheumatoid arthritis | CMV | MTX + TOF regimen was stopped due to CMVR. IRU surged during anti-CMV treatment |

| Lavine, 2018 [42] | Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma | Non-detectable | After chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplant therapy |

| Sánchez-Vicente, 2019 [44] | Hairy cell leukaemia | HSV | After the last cycle of pentostatin |

| Tai, 2021 [48] | Good syndrome | CMV | After multiple doses of GCSF |

| Saricay, 2023 [43] | Acute leukaemia | CMV | During concurrent chemotherapy and systemic antiviral therapy |

CMV cytomegalovirus, CMVR cytomegalovirus retinitis, GCSF granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, IRU immune recovery uveitis, MTX methotrexate, TOF tofacitinib

In summary, IRU is a clinical diagnosis that is based on a set of exclusion criteria and a combination of clinical and laboratory findings and requires careful assessment by a multidisciplinary team.

Risk factors

Several risk factors are associated with the development of IRU:

Immune recovery with a rapid rise in CD4 + T cell count (specifically, a CD4 + count 100 to 199 cells/microliter) (Odds ratio (OR 21.8) [25];

Intravitreal cidofovir (OR 19.1) [25]

CMVR extension area of ≥ 25% (OR 2.52) [25].

On the other hand, the presence of a posterior pole lesion (area including a 1500-µm radius around the optic nerve and a 3000-µm radius around the center of the macula; OR 0.43), male gender (OR 0.23), and HIV load > 400 copies/milliliter (OR 0.26) were found to be associated with reduced IRU risk [25].

Other factors that are currently unidentified might impact the susceptibility and severity of IRU. Therefore, additional research is warranted to identify and understand these factors better.

Treatment

The management of IRU involves considering various factors, including the extent and activity of the underlying CMV retinitis, the presence or absence of non-ocular IRIS, the site of intraocular inflammation, the existence of any associated ocular complications, particularly macular edema, and the patient’s general health [1].

Medical treatment

Topical corticosteroids are typically used for anterior chamber inflammation, while mild vitritis without macular edema may simply be observed [54, 55].

Short courses of oral corticosteroids or sub-Tenon steroid injections or periocular corticosteroids (e.g., triamcinolone acetonide) are reserved for cases of severe vitritis and/or CME, but their effectiveness is limited [31, 54]. Fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implants have shown promising improvements in CME associated with IRU [56]. Intravitreal corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone) may be considered in refractory cases, but caution must be taken due to the risk of increased intraocular pressure, cataracts, and CMVR reactivation, which can be prevented by restarting anti-CMV therapy [19, 54, 57]. Additionally, steroid use is a significant risk factor for the occurrence of tubercular uveitis, so it is important to monitor for this condition [58, 59].

Discontinuing antiretroviral therapy is not recommended because it reduces the CD4 + T lymphocyte count and increases the risk of opportunistic infections [21]. Patients with CMVR who are receiving antiretroviral regimens should continue with anti-CMV maintenance therapy (Table 2) until the IRU is resolved and sustained immune recovery is achieved (CD4 + T lymphocytes ≥ 100 cells/µL for 3–6 months) [21]. Even after discontinuation of anti-CMV therapy, patients with a history of CMVR should be closely monitored at 3-month intervals, as they remain at risk for recurrence [21]. International guidelines recommend initiation of HAART within two weeks of commencing anti-CMV therapy in HIV/CMVR patients, although these recommendations are based on expert opinions and not empirical evidence [60, 61].

Table 2.

Treatment recommendations for CMVR.

Adapted from Port et al., (2017) [9]

| Recommended treatment regime | Alternate regime | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

|

Induction -Oral Valganciclovir 900 mg twice daily -Intravenous Ganciclovir 5 mg/kg twice daily for 14–21 days -Intravitreal Ganciclovir 2 mg/0.1 mL twice weekly Maintenance -Oral Valganciclovir 900 mg daily -Intravenous Ganciclovir 5 mg/kg/day -Intravitreal Ganciclovir 2 mg/0.1 mL weekly |

Induction - Intravenous Foscarnet 90 mg/kg twice daily for 14 days -Intravenous Cidofovir 5 mg/kg weekly for 3 weeks Maintenance -Intravenous Foscarnet 120 mg/kg/day -Intravenous Cidofovir 5 mg/kg every 2 weeks Intravitreal Induction -Foscarnet 1.2–2.4 mg 1–2 times weekly -Cidofovir 20 μg 1–8 times as needed to halt retinitis Intravitreal Maintenance -Foscarnet 1.2 mg weekly -Cidofovir 20 μg every 5–6 weeks |

Ganciclovir/Valganciclovir: Myelosuppression Foscarnet: Nausea and vomiting, electrolyte disturbance, nephrotoxicity Cidofovir: nephrotoxicity, anterior uveitis CMV mutations in UL54 or UL97 genes cause ganciclovir, foscarnet and cidofovir resistance [62] |

Of note, Cidofovir should not be used if immune recovery is expected due to its association with IRU

Furthermore, the discoveries regarding the involvement of the HIV-1 Tat protein in disrupting the integrity of the BRB suggest that blocking the activity of HIV-1 Tat could be a crucial component of future therapeutic approaches for managing CME associated with IRU [63].

More recently, some studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents in treating IRU-induced CME, especially aflibercept [64]. Increased levels of proangiogenic factors such as VEGF and placental growth factor (PlGF) have been reported in ocular inflammation, and these factors can promote cell proliferation, migration, and vascular permeability [65]. Intraocular bevacizumab and aflibercept have anti-inflammatory effects, and aflibercept has a higher affinity for VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and PlGF than bevacizumab and ranibizumab [66, 67]. These differences may be responsible for the better effect of aflibercept in treating IRU-induced CME [64].

A substantial challenge arises in balancing treatment decisions, notably when facing complications like macular edema refractory to diverse interventions, even amid sustained immune recovery. This intricate balancing act necessitates a nuanced consideration of risks and benefits associated with off-label treatments.

Surgical management

Surgical treatment plays an important role in managing various retinal conditions and can significantly improve visual outcomes for patients. Vitreomacular traction syndrome, ERM, cataract, and proliferative vitreoretinopathy are some of the possible indications for surgery [1].

Discussion

This comprehensive and updated review provides an in-depth analysis of IRU, covering various aspects, including epidemiology, pathophysiology, biomarkers, clinical presentation, risk factors, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and treatment. The findings offer valuable insights for clinical practice and highlight potential areas for future research in the field of IRU.

Immunosuppression, especially when HIV patients have a CD4 + cell count lower than 50 cells/μL, is strongly associated with an increased risk of diverse ocular presentations [12]. This underscores the critical importance of regular ocular evaluations and screening for visual impairment in this population [1, 5]. Among the opportunistic infections observed in late-stage HIV infection, CMVR emerges as the most common ocular manifestation [6, 7]. While HAART has proven effective in reducing opportunistic infections, it has also been associated with an increased incidence of IRIS [11, 13, 14].

IRIS is a tissue-destructive inflammatory response characterized by the improvement of a previously incompetent human immune system, resulting in the worsening of clinical symptoms due to a vigorous inflammatory response [15, 68]. Initially, recognized in the context of HIV infection, IRIS continues to be most frequently encountered in this clinical setting [69]. This highlights the complex interplay between immune reconstitution and inflammatory responses in HIV patients.

Notably, despite the implementation of maintenance anti-CMV therapy following HAART initiation, cases of IRU can still occur, suggesting that the underlying mechanisms driving IRU might extend beyond CMV infection alone [23]. Interestingly, some patients develop IRU with only a minimal increase in CD4 + counts, indicating that IRU can manifest even in individuals with modest immune recovery. This underscores the need for vigilant monitoring and early detection of IRU in HIV-infected patients, irrespective of the magnitude of CD4 + cell count improvement.

Optimal timing is crucial in the management of IRU. Initiating HAART before completing induction therapy for CMVR may increase the risk of developing IRU [1, 22]. Expert opinions recommend initiating HAART within two weeks of commencing anti-CMV therapy in HIV/CMVR patients [60, 61]. Furthermore, the risk of IRU-induced complications appears to correlate with the absolute difference in CD4 + counts between HAART initiation and IRU development, emphasizing the significance of regular monitoring and ophthalmologic evaluations to promptly identify potential complications [41].

An accurate diagnosis of IRU relies on a set of exclusion criteria and a comprehensive assessment incorporating clinical and laboratory findings [1, 9]. It is crucial to differentiate IRU from other ocular conditions, as this has significant implications for appropriate management. Complex cases may require advanced diagnostic modalities such as multimodal imaging, ocular PCR, and diagnostic vitrectomy to aid in the differential diagnosis [42].

While IRU has primarily been studied in HIV-infected patients, it is noteworthy that similar IRU-like responses have been observed in patients with diverse etiologies when immunosuppression is reversed [70]. This broader spectrum of conditions associated with IRU-like responses, ranging from lymphoma to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, highlights the multifactorial nature of this inflammatory phenomenon [42–53]. This suggests that IRU may be a broader spectrum condition than currently described, as several cases have occurred in non-HIV patients with different previous ocular infections, challenging our understanding of IRU. In addition to CMV, ocular IRIS can be observed with other ocular opportunistic infections, including ocular tuberculosis and Cryptococcus neoformans [71, 72].

The establishment of the concept, definition, and diagnostic criteria of non-HIV-type IRIS would aid clinical decision-making regarding the continuation of treatment for the original disease. This new concept has the potential to benefit patients by providing tailored management strategies. Further complexity emerges in the absence of fluoxograms, challenging practitioners in their diagnostic and management toolkits.

Treatment strategies for IRU primarily aim to control inflammation and preserve visual function, with steroids being the standard therapy [54, 55]. Ongoing anti-CMV therapy can be beneficial in preventing CMVR reactivation, and diligent monitoring is essential for patients with a history of CMVR [7, 54, 57]. Antiretroviral therapy should not be discontinued, as it increases the risk of opportunistic infections and compromises immune recovery [21]. Patients with CMVR who are receiving antiretroviral regimens should continue with anti-CMV maintenance therapy until IRU has resolved and sustained immune recovery is achieved, described as CD4 + T lymphocytes ≥ 100 cells/μL for 3–6 months [21].

Exciting research has highlighted the involvement of the HIV-1 Tat protein in disrupting the BRB, suggesting that targeting this protein may hold promise for managing CME associated with IRU [63]. Moreover, studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of anti-VEGF agents, particularly aflibercept, in treating IRU-induced CME [64–67]. These emerging therapeutic avenues offer potential breakthroughs in the management of IRU and warrant further investigation. However, considering aspects related to cytokine biomarkers and the inflammatory pathophysiology of IRIS, the use of TNF inhibitors, anti-IL-6, or other biological treatments for IRU remains questionable [73]. Controlled studies supporting the use of these pharmacologic interventions in IRIS and IRU are limited, and current recommendations are largely based on case series.

Conclusion

In summary, IRU is an intraocular inflammation and may be the sole manifestation of IRIS, involving a complex interplay between immune reconstitution and inflammatory responses. Notably, IRU can occur even in individuals with modest immune recovery and may have underlying mechanisms beyond CMV infection alone. Therefore, diligent monitoring and early detection of IRU are essential, considering the potential for diverse etiologies of immunosuppression.

Accurate diagnosis of IRU relies on comprehensive assessments that incorporate clinical and laboratory findings, possibly utilizing advanced diagnostic modalities when necessary. The broad spectrum of conditions associated with IRU-like responses challenges our current understanding and emphasizes the need for a comprehensive definition and diagnostic criteria for non-HIV-type IRIS. Such an approach would facilitate clinical decision-making and enable tailored management strategies for patients.

Further research is warranted to optimize treatment approaches, explore novel therapeutic targets, and improve patient outcomes for both HIV and non-HIV individuals affected by IRU. Advancements in these areas will contribute to better understanding, management, and ultimately, the overall well-being of patients affected by this complex inflammatory condition.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Rui Proença, MD, PhD, from the Department of Ophthalmology, Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra, for critically reviewing the article.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Rita Pinto Proença had the idea for the article. Nuno Rodrigues Alves, Catarina Mota and Catarina Barão performed the literature search. Nuno Rodrigues Alves, Lívio Costa, and Rita Pinto Proença wrote the article. All contributors had final review and approval. Nuno Rodrigues Alves is the guarantor.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on). Open Access funding provided thanks to the FCCN/b-ON agreement with Springer Nature Open Choice Journal – Transformer Journal.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Urban B, Bakunowicz-Łazarczyk A, Michalczuk M (2014) Immune recovery uveitis: pathogenesis, clinical symptoms, and treatment. Mediators Inflamm 2014:1–10. 10.1155/2014/971417 10.1155/2014/971417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sudharshan S, Biswas J (2008) Introduction and immunopathogenesis of acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Indian J Ophthalmol 56:357. 10.4103/0301-4738.42411 10.4103/0301-4738.42411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sudharshan S, Nair N, Curi A et al (2020) Human immunodeficiency virus and intraocular inflammation in the era of highly active anti retroviral therapy – an update. Indian J Ophthalmol 68:1787. 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1248_20 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1248_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nussenblatt RB, Clifford Lane H (1998) Human immunodeficiency virus disease: changing patterns of intraocular inflammation. Am J Ophthalmol 125:374–382. 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)80149-4 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)80149-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen QD, Kempen JH, Bolton SG et al (2000) Immune recovery uveitis in patients with AIDS and cytomegalovirus retinitis after highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Ophthalmol 129:634–639. 10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00356-1 10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00356-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schrier RD, Song MK, Smith IL et al (2006) Intraocular viral and immune pathogenesis of immune recovery uveitis in patients with healed cytomegalovirus retinitis. Retina 26:165–169. 10.1097/00006982-200602000-00007 10.1097/00006982-200602000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munro M, Yadavalli T, Fonteh C et al (2019) Cytomegalovirus retinitis in HIV and non-HIV individuals. Microorganisms 8:55. 10.3390/microorganisms8010055 10.3390/microorganisms8010055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zegans ME, Christopher Walton R, Holland GN et al (1998) Transient vitreous inflammatory reactions associated with combination antiretroviral therapy in patients with AIDS and cytomegalovirus retinitis. Am J Ophthalmol 125:292–300. 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)80134-2 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)80134-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Port AD, Orlin A, Kiss S et al (2017) Cytomegalovirus retinitis: a review. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 33:224–234. 10.1089/jop.2016.0140 10.1089/jop.2016.0140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jabs DA (2011) Cytomegalovirus retinitis and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome—bench to bedside: LXVII Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol 151:198-216.e1. 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.10.018 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yanoff M, Duker JS (2019) Ophthalmology. Elsevier Inc, Fifth [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vrabec TR (2004) Posterior segment manifestations of HIV/AIDS. Surv Ophthalmol 49:131–157. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.12.008 10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sudharshan S, Kaleemunnisha S, Banu AA et al (2013) Ocular lesions in 1,000 consecutive HIV-positive patients in India: a long-term study. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect 3:2. 10.1186/1869-5760-3-2 10.1186/1869-5760-3-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ratnam I, Chiu C, Kandala N-B, Easterbrook PJ (2006) Incidence and risk factors for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in an ethnically diverse HIV type 1-infected cohort. Clin Infect Dis 42:418–427. 10.1086/499356 10.1086/499356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Müller M, Wandel S, Colebunders R et al (2010) Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in patients starting antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 10:251–261. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70026-8 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70026-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Behrens GMN, Meyer D, Stoll M, Schmidt RE (2000) Immune reconstitution syndromes in human immunodeficiency virus infection following effective antiretroviral therapy. Immunobiology 202:186–193. 10.1016/S0171-2985(00)80065-0 10.1016/S0171-2985(00)80065-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manzardo C, Guardo AC, Letang E et al (2015) Opportunistic infections and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-1-infected adults in the combined antiretroviral therapy era: a comprehensive review. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 13:751–767. 10.1586/14787210.2015.1029917 10.1586/14787210.2015.1029917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.French MA, Price P, Stone SF (2004) Immune restoration disease after antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 18:1615–1627. 10.1097/01.aids.0000131375.21070.06 10.1097/01.aids.0000131375.21070.06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holland GN (2008) AIDS and ophthalmology: the first quarter century. Am J Ophthalmol 145(3):397-408.e1. 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.12.001 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang M, Kamoi K, Zong Y et al (2023) Human immunodeficiency virus and uveitis Viruses 15:444. 10.3390/v15020444 10.3390/v15020444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sen HN, Albini TA, Burkholder BM et al (2022) 2022–2023 Basic and clinical science course, Section 9: Uveitis and Ocular Inflammation. American Academy of Ophthalmology, San Francisco

- 22.Ortega-Larrocea G, Espinosa E, Reyes-Terán G (2005) Lower incidence and severity of cytomegalovirus-associated immune recovery uveitis in HIV-infected patients with delayed highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 19:735–738. 10.1097/01.aids.0000166100.36638.97 10.1097/01.aids.0000166100.36638.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuppermann BD, Holland GN (2000) Immune recovery uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol 130:103–106. 10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00537-7 10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00537-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holland GN (1999) Immune recovery uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 7:215–221. 10.1076/ocii.7.3.215.4010 10.1076/ocii.7.3.215.4010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kempen JH, Min YI, Freeman WR et al (2006) Risk of immune recovery uveitis in patients with AIDS and cytomegalovirus retinitis. Ophthalmology 113:684–694. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.10.067 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.10.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karavellas MP, Plummer DJ, Macdonald JC et al (1999) Incidence of immune recovery vitritis in cytomegalovirus retinitis patients following institution of successful highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 179:697–700. 10.1086/314639 10.1086/314639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Y-C, Yang C-H, Lin C-P et al (2008) Cytomegalovirus retinitis and immune recovery uveitis in AIDS patients treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy in Taiwanese. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 16:83–87. 10.1080/09273940802056307 10.1080/09273940802056307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jabs DA, Ahuja A, Van Natta ML et al (2015) Long-term outcomes of cytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of modern antiretroviral therapy: results from a United States cohort. Ophthalmology 122:1452–1463. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.02.033 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.02.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chatterjee N, Callen S, Seigel GM, Buch SJ (2011) HIV-1 Tat-mediated neurotoxicity in retinal cells. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 6:399–408. 10.1007/s11481-011-9257-8 10.1007/s11481-011-9257-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kosobucki BR, Goldberg DE, Bessho K et al (2004) Valganciclovir therapy for immune recovery uveitis complicated by macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol 137:636–638. 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.11.008 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karavellas MP, Azen SP, Macdonald JC et al (2001) Immune recovery vitritis and uveitis in AIDS. Retina 21:1–9. 10.1097/00006982-200102000-00001 10.1097/00006982-200102000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rios LS, Vallochi AL, Muccioli C et al (2005) Cytokine profile in response to Cytomegalovirus associated with immune recovery syndrome after highly active antiretroviral therapy. Can J Ophthalmol 40:711–720. 10.1016/S0008-4182(05)80087-0 10.1016/S0008-4182(05)80087-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iyer JV, Connolly J, Agrawal R et al (2013) Cytokine analysis of aqueous humor in HIV patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Cytokine 64:541–547. 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.08.006 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Modorati G, Miserocchi E, Brancato R (2005) Immune recovery uveitis and human leukocyte antigen typing: a report on four patients. Eur J Ophthalmol 15:607–609. 10.1177/112067210501500511 10.1177/112067210501500511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duraikkannu D, Akbar AB, Sudharshan S et al (2023) Differential expression of miRNA-192 is a potential biomarker for HIV associated immune recovery uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 31:566–575. 10.1080/09273948.2022.2106247 10.1080/09273948.2022.2106247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartigan-O’Connor DJ, Jacobson MA, Tan QX, Sinclair E (2011) Development of cytomegalovirus (CMV) immune recovery uveitis is associated with Th17 cell depletion and poor systemic CMV-specific T cell responses. Clin Infect Dis 52:409–417. 10.1093/cid/ciq112 10.1093/cid/ciq112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pei L, Fukutani KF, Tibúrcio R, et al (2021) Plasma metabolomics reveals dysregulated metabolic signatures in HIV-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Front Immunol 12. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.693074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Ramon-Luing LA, Ocaña-Guzman R, Téllez-Navarrete NA, et al (2021) High levels of tnf-α and tim-3 as a biomarker of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in people with hiv infection. Life 11. 10.3390/life11060527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Whitcup SM (1999) Discontinuation of anticytomegalovirus therapy in patients with HIV infection and cytomegalovirus retinitis. JAMA 282:1633. 10.1001/jama.282.17.1633 10.1001/jama.282.17.1633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karavellas MP, Song M, Macdonald JC, Freeman WR (2000) Long-term posterior and anterior segment complications of immune recovery uveitis associated with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Am J Ophthalmol 130:57–64. 10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00528-6 10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00528-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeo TH, Yeo TK, Wong EP et al (2016) Immune recovery uveitis in HIV patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of HAART therapy—a 5-year study from Singapore. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect 6:41. 10.1186/s12348-016-0110-3 10.1186/s12348-016-0110-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lavine JA, Singh AD, Baynes K, Srivastava SK (2021) Immune recovery uveitis-like syndrome mimicking recurrent T-cell lymphoma after autologous bone marrow transplant. Retin Cases Brief Rep 15:407–411. 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000829 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yavuz Saricay L, Baldwin G, Leake K et al (2023) Cytomegalovirus retinitis and immune recovery uveitis in a pediatric patient with leukemia. J Am Assoc Pedia Ophthalmol Strabismus 27:52–55. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2022.10.004 10.1016/j.jaapos.2022.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sánchez-Vicente JL, Rueda-Rueda T, Moruno-Rodríguez A et al (2019) Respuesta similar a la uveítis de recuperación inmune en un paciente con retinitis herpética como complicación de una leucemia de células peludas. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol 94:545–550. 10.1016/j.oftal.2019.07.012 10.1016/j.oftal.2019.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baker ML, Allen P, Shortt J et al (2007) Immune recovery uveitis in an HIV-negative individual†. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 35:189–190. 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01439.x 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01439.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bessho K, Schrier RD, Freeman WR (2007) Immune recovery uveitis in a CMV retinitis patient without HIV infection. Retin Cases Brief Rep 1:52–53. 10.1097/01.ICB.0000256952.24403.42 10.1097/01.ICB.0000256952.24403.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miserocchi E, Modorati G, Brancato R (2005) Immune recovery uveitis in a iatrogenically immunosuppressed patient. Eur J Ophthalmol 15:510–512. 10.1177/112067210501500417 10.1177/112067210501500417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tai C-C, Chao Y-J, Hwang D-K (2022) Granulocyte colony stimulating factor-induced immune recovery uveitis associated with cytomegalovirus retinitis in the setting of good syndrome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 30:1519–1521. 10.1080/09273948.2021.1881565 10.1080/09273948.2021.1881565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yanagisawa K, Ogawa Y, Hosogai M et al (2017) Cytomegalovirus retinitis followed by immune recovery uveitis in an elderly patient with rheumatoid arthritis undergoing administration of methotrexate and tofacitinib combination therapy. J Infect Chemother 23:572–575. 10.1016/j.jiac.2017.03.002 10.1016/j.jiac.2017.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Downes KM, Tarasewicz D, Weisberg LJ, Cunningham ET (2016) Good syndrome and other causes of cytomegalovirus retinitis in HIV-negative patients—case report and comprehensive review of the literature. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect 6:1–19 10.1186/s12348-016-0070-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wimmersberger Y, Balaskas K, Gander M et al (2011) Immune recovery uveitis occurring after chemotherapy and ocular CMV infection in chronic lymphatic leukaemia. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 228:358–359 10.1055/s-0031-1273226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agarwal A, Kumari N, Trehan A et al (2014) Outcome of cytomegalovirus retinitis in immunocompromised patients without Human Immunodeficiency Virus treated with intravitreal ganciclovir injection. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 252:1393–1401. 10.1007/s00417-014-2587-5 10.1007/s00417-014-2587-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuo IC, Kempen JH, Dunn JP et al (2004) Clinical characteristics and outcomes of cytomegalovirus retinitis in persons without human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Ophthalmol 138:338–346. 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.04.015 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.EL-Bradey MH, Cheng L, Song M-K et al (2004) Long-term results of treatment of macular complications in eyes with immune recovery uveitis using a graded treatment approach. Retina 24:376–382. 10.1097/00006982-200406000-00007 10.1097/00006982-200406000-00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henderson HWA, Mitchell SM (1999) Treatment of immune recovery vitritis with local steroids. Br J Ophthalmol 83:540–545. 10.1136/bjo.83.5.540 10.1136/bjo.83.5.540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu J, Coassin M, Stewart JM (2011) Fluocinolone acetonide implant (Retisert) for chronic cystoid macular edema in two patients with AIDS and a history of cytomegalovirus retinitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 19:206–209. 10.3109/09273948.2010.538120 10.3109/09273948.2010.538120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morrison VL, Kozak I, LaBree LD et al (2007) Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for the treatment of immune recovery uveitis macular edema. Ophthalmology 114:334–339. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.013 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Agarwal A, Handa S, Aggarwal K et al (2018) The role of dexamethasone implant in the management of tubercular uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 26:884–892. 10.1080/09273948.2017.1400074 10.1080/09273948.2017.1400074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jain L, Panda KG, Basu S (2018) Clinical outcomes of adjunctive sustained-release intravitreal dexamethasone implants in tuberculosis-associated multifocal Serpigenoid Choroiditis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 26:877–883. 10.1080/09273948.2017.1383446 10.1080/09273948.2017.1383446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.(2023) Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Available at https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-andadolescent- opportunistic-infection. Accessed (8th of May 2023)

- 61.WHO (2015) Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV, p 76 [PubMed]

- 62.Erice A (1999) Resistance of human cytomegalovirus to antiviral drugs. Clin Microbiol Rev 12:286–297. 10.1128/CMR.12.2.286 10.1128/CMR.12.2.286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Che X, He F, Deng Y et al (2014) HIV-1 Tat-mediated apoptosis in human blood-retinal barrier-associated cells. Plos One 9:e95420. 10.1371/journal.pone.0095420 10.1371/journal.pone.0095420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rothova A, ten Berge JC, Vingerling JR (2020) Intravitreal aflibercept for treatment of macular oedema associated with immune recovery uveitis. Acta Ophthalmol 98:e922–e923. 10.1111/aos.14451 10.1111/aos.14451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kozak I, Shoughy SS, Stone DU (2017) Intravitreal antiangiogenic therapy of uveitic macular edema: a review. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 33:235–239. 10.1089/jop.2016.0118 10.1089/jop.2016.0118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sato T, Takeuchi M, Karasawa Y et al (2018) Intraocular inflammatory cytokines in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration before and after initiation of intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF inhibitor. Sci Rep 8. 10.1038/s41598-018-19594-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Papadopoulos N, Martin J, Ruan Q et al (2012) Binding and neutralization of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and related ligands by VEGF Trap, ranibizumab and bevacizumab. Angiogenesis 15:171–185. 10.1007/s10456-011-9249-6 10.1007/s10456-011-9249-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shahani L, Hamill RJ (2016) Therapeutics targeting inflammation in the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Transl Res 167:88–103. 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.07.010 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.French MAH, Mallal SA, Dawkins RL (1992) Zidovudine-induced restoration of cell-mediated immunity to mycobacteria in immunodeficient HIV-infected patients. AIDS 6:1293–1298. 10.1097/00002030-199211000-00009 10.1097/00002030-199211000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun H-Y, Singh N (2009) Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in non-HIV immunocompromised patients. Curr Opin Infect Dis 22:394–402. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32832d7aff 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32832d7aff [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walker NF, Stek C, Wasserman S et al (2018) The tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 13:512–521. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000502 10.1097/COH.0000000000000502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dhasmana DJ, Dheda K, Ravn P et al (2008) Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. Drugs 68:191–208. 10.2165/00003495-200868020-00004 10.2165/00003495-200868020-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sueki H, Mizukawa Y, Aoyama Y (2018) Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in non-HIV immunosuppressed patients. J Dermatol 45:3–9. 10.1111/1346-8138.14074 10.1111/1346-8138.14074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]