Approaches to the management of heart failure can be both non-pharmacological and pharmacological; each approach complements the other. This article will discuss non-pharmacological management.

Non-pharmacological measures for the management of heart failure

Compliance—give careful advice about disease, treatment, and self help strategies

Diet—ensure adequate general nutrition and, in obese patients, weight reduction

Salt—advise patients to avoid high salt content foods and not to add salt (particularly in severe cases of congestive heart failure)

Fluid—urge overloaded patients and those with severe congestive heart failure to restrict their fluid intake

Alcohol—advise moderate alcohol consumption (abstinence in alcohol related cardiomyopathy)

Smoking—avoid smoking (adverse effects on coronary disease, adverse haemodynamic effects)

Exercise—regular exercise should be encouraged

Vaccination—patients should consider influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations

Counselling and education of patients

Effective counselling and education of patients, and of the relatives or carers, is important and may enhance long term adherence to management strategies. Simple explanations about the symptoms and signs of heart failure, including details on drug and other treatment strategies, are valuable. Emphasis should be placed on self help strategies for each patient; these should include information on the need to adhere to drug treatment. Some patients can be instructed how to monitor their weight at home on a daily basis and how to adjust the dose of diuretics as advised; sudden weight increases (>2 kg in 1-3 days), for example, should alert a patient to alter his or her treatment or seek advice.

Lifestyle measures

Urging patients to alter their lifestyle is important in the management of chronic heart failure. Social activities should be encouraged, however, and care should be taken to ensure that patients avoid social isolation. If possible, patients should continue their regular work, with adaptations to accommodate a reduced physical capacity where appropriate.

Contraceptive advice

Advice on contraception should be offered to women of childbearing potential, particularly those patients with advanced heart failure (class III-IV in the New York Heart Association's classification), in whom the risk of maternal morbidity and mortality is high with pregnancy and childbirth. Current hormonal contraceptive methods are much safer than in the past: low dose oestrogen and third generation progestogen derivatives are associated with a relatively low thromboembolic risk.

Intrauterine devices are a suitable form of contraception, although these may be a problem in patients with primary valvar disease, in view of the risks of infection and risks associated with oral anticoagulation

Smoking

Cigarette smoking should be strongly discouraged in patients with heart failure. In addition to the well established adverse effects on coronary disease, which is the underlying cause in a substantial proportion of patients, smoking has adverse haemodynamic effects in patients with congestive heart failure. For example, smoking tends to reduce cardiac output, especially in patients with a history of myocardial infarction.

Menopausal women with heart failure

Observational data indicate that hormone replacement therapy reduces the risk of coronary events in postmenopausal women

However, there is limited prospective evidence to advise the use of such therapy in postmenopausal women with heart failure

Nevertheless, there may be an increased risk of venous thrombosis in postmenopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy, which may exacerbate the risk associated with heart failure

Other adverse haemodynamic effects include an increase in heart rate and systemic blood pressure (double product) and mild increases in pulmonary artery pressure, ventricular filling pressures, and total systemic and pulmonary vascular resistance.

The peripheral vasoconstriction may contribute to the observed mild reduction in stroke volume, and thus smoking increases oxygen demand and also decreases myocardial oxygen supply owing to reduced diastolic filling time (with faster heart rates) and increased carboxyhaemoglobin concentrations.

Alcohol

In general, alcohol consumption should be restricted to moderate levels, given the myocardial depressant properties of alcohol. In addition to the direct toxic effects of alcohol on the myocardium, a high alcohol intake predisposes to arrhythmias (especially atrial fibrillation) and hypertension and may lead to important alterations in fluid balance. The prognosis in alcohol induced cardiomyopathy is poor if consumption continues, and abstinence should be advised. Abstinence can result in marked improvements, with echocardiographic studies showing substantial clinical benefit and improvements in left ventricular function. Resumed alcohol consumption may subsequently lead to acute or worsening heart failure.

Community and social support

Community support is particularly important for elderly or functionally restricted patients with chronic heart failure

Support may help to improve the quality of life and reduce admission rates

Social services support and community based interventions, with advice and assistance for close relatives, are also important

Managing cachexia in chronic heart failure

Combined management by physician and dietician is recommended

Alter size and frequency of meals

Ensure a higher energy diet

Supplement diet with (a) water soluble vitamins (loss associated with diuresis), (b) fat soluble vitamins (levels reduced as a result of poor absorption), and (c) fish oils

Immunisation and antiobiotic prophylaxis

Chronic heart failure predisposes to and can be exacerbated by pulmonary infection, and influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations should therefore be considered in all patients with heart failure. Antibiotic prophylaxis, for dental and other surgical procedures, is mandatory in patients with primary valve disease and prosthetic heart valves.

Diet and nutrition

Although controlled trials offer only limited information on diet and nutritional measures, such measures are as important in heart failure, as in any other chronic illness, to ensure adequate and appropriate nutritional balance. Poor nutrition may contribute to cardiac cachexia, although malnutrition is not limited to patients with obvious weight loss and muscle wasting.

Patients with chronic heart failure are at an increased risk from malnutrition owing to (a) a decreased intake resulting from a poor appetite, which may be related to drug treatment (for example, aspirin, digoxin), metabolic disturbance (for example, hyponatraemia or renal failure), or hepatic congestion; (b) malabsorption, particularly in patients with severe heart failure; and (c) increased nutritional requirements, with patients who have congestive heart failure having an increase of up to 20% in basal metabolic rate. These factors may contribute to a net catabolic state where lean muscle mass is reduced, leading to an increase in symptoms and reduced exercise capacity. Indeed, cardiac cachexia is an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. A formal nutritional assessment should thus be considered in those patients who appear to have a poor nutritional state.

Commonly consumed processed foods that have a high sodium content

Cheese

Sausages

Crisps, salted peanuts

Milk and white chocolate

Tinned soup and tinned vegetables

Ham, bacon, tinned meat (eg corned beef)

Tinned fish (eg sardines, salmon, tuna)

Smoked fish

Weight loss in obese patients should be encouraged as excess body mass increases cardiac workload during exercise. Weight reduction in obese patients to within 10% of the optimal body weight should be encouraged.

Salt restriction

No randomised studies have addressed the role of salt restriction in congestive heart failure. Nevertheless restriction to about 2 g of sodium a day may be useful as an adjunct to treatment with high dose diuretics, particularly if the condition is advanced.

In general, patients should be advised that they should avoid foods that are rich in salt and not to add salt to their food at the table.

Fresh produce, such as fruit, vegetables, eggs, and fish, has a relatively low salt content

Fluid intake

Fluid restriction (1.5-2 litres daily) should be considered in patients with severe symptoms, those requiring high dose diuretics, and those with a tendency towards excessive fluid intake. High fluid intake negates the positive effects of diuretics and induces hyponatraemia.

Exercise training and rehabilitation

Exercise training has been shown to benefit patients with heart failure: patients show an improvement in symptoms, a greater sense of wellbeing, and better functional capacity. Exercise does not, however, result in obvious improvement in cardiac function.

Effects of deconditioning in heart failure

| Peripheral alterations | Increased peripheral vascular resistance; impaired oxygen utilisation during exercise |

| Abnormalities of autonomic control | Enhanced sympathetic activation; vagal withdrawal; reduced baroreflex sensitivity |

| Skeletal muscle abnormalities | Reduced mass and composition |

| Reduced functional capacity | Reduced exercise tolerance; reduced peak oxygen consumption |

| Psychological effects | Reduced activity; reduced overall sense of wellbeing |

All stable patients with heart failure should be encouraged to participate in a supervised, simple exercise programme. Although bed rest (“armchair treatment”) may be appropriate in patients with acute heart failure, regular exercise should be encouraged in patients with chronic heart failure. Indeed, chronic immobility may result in loss of muscle mass in the lower limb and generalised physical deconditioning, leading to a further reduction in exercise capacity and a predisposition to thromboembolism. Deconditioning itself may be detrimental, with peripheral alterations and central abnormalities leading to vasoconstriction, further deterioration in left ventricular function, and greater reduction in functional capacity.

Importantly, regular exercise has the potential to slow or stop this process and exert beneficial effects on the autonomic profile, with reduced sympathetic activity and enhanced vagal tone, thus reversing some of the adverse consequences of heart failure. Large prospective clinical trials will establish whether these beneficial effects improve prognosis and reduce the incidence of sudden death in patients with chronic heart failure.

Regular exercise should therefore be advocated in stable patients as there is the potential for improvements in exercise tolerance and quality of life, without deleterious effects on left ventricular function. Cardiac rehabilitation services offer benefit to this group, and patients should be encouraged to develop their own regular exercise routine, including walking, cycling, and swimming. Nevertheless, patients should know their limits, and excessive fatigue or breathlessness should be avoided. In the first instance, a structured walking programme would be the easiest to adopt.

Beneficial effects of exercise in chronic heart failure

Has positive effects on:

Skeletal muscle

Autonomic function

Endothelial function

Neurohormonal function

Insulin sensitivity

No positive effects on survival have been shown

Treatment of underlying disease

Treatment should also be aimed at slowing or reversing any underlying disease process.

Hypertension

Good blood pressure control is essential, and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors are the drugs of choice in patients with impaired systolic function, in view of their beneficial effects on slowing disease progression and improving prognosis. In cases of isolated diastolic dysfunction, either β blockers or calcium channel blockers with rate limiting properties—for example, verapamil, diltiazem—have theoretical advantages. If severe left ventricular hypertrophy is the cause of diastolic dysfunction, however, an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor may be more effective at inducing regression of left ventricular hypertrophy. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists should be considered as an alternative if cough that is induced by angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors is problematic.

Surgery

If coronary heart disease is the underlying cause of chronic heart failure and if cardiac ischaemia is present, the patient may benefit from coronary revascularisation, including coronary angioplasty or coronary artery bypass grafting. Revascularisation may also improve the function of previously hibernating myocardium. Valve replacement or valve repair should be considered in patients with haemodynamically important primary valve disease.

Role of surgery in heart failure

| Type of surgery | Reason |

|---|---|

| Coronary revascularisation (PTCA, CABG) | Angina, reversible ischaemia, hibernating myocardium |

| Valve replacement (or repair) | Significant valve disease (aortic stenosis, mitral regurgitation) |

| Permanent pacemakers and implantable cardiodefibrillators | Bradycardias; resistant ventricular arrhythmias |

| Cardiac transplantation | End stage heart failure |

| Ventricular assist devices | Short term ventricular support—eg awaiting transplantation |

| Novel surgical techniques | Limited role (high mortality, limited evidence of substantial benefit) |

PTCA=percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; CABG=coronary artery bypass graft.

Cardiac transplantation is now established as the treatment of choice for some patients with severe heart failure who remain symptomatic despite intensive medical treatment. It is associated with a one year survival of about 90% and a 10 year survival of 50-60%, although it is limited by the availability of donor organs. Transplantation should be considered in younger patients (aged <60 years) who are without severe concomitant disease (for example, renal failure or malignancy).

Bradycardias are managed with conventional permanent cardiac pacing, although a role is emerging for biventricular cardiac pacing in some patients with resistant severe congestive heart failure. Implantable cardiodefibrillators are well established in the treatment of some patients with resistant life threatening ventricular arrhythmias. New surgical approaches such as cardiomyoplasty and ventricular reduction surgery (Batista procedure) are rarely used owing to the high associated morbidity and mortality and the lack of conclusive trial evidence of substantial benefit.

Key references

Demakis JG, Proskey A, Rahimtoola SH, Jamil M, Sutton GC, Rosen KM, et al. The natural course of alcoholic cardiomyopathy. Ann Intern Med 1974;80:293-7.

The Task Force of the Working Group on Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines on the treatment of heart failure. Eur Heart J 1997;18:736-53.

Kostis JB, Rosen RC, Cosgrove NM, Shindler DM, Wilson AC. Nonpharmacologic therapy improves functional and emotional status in congestive heart failure. Chest 1994;106:996-1001.

McKelvie RS, Teo KK, McCartney N, Humen D, Montague T, Yusuf S. Effects of exercise training in patients with congestive heart failure: a critical review. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;25:789-96.

Figure.

Self help strategies for patients with heart failure

Figure.

Heart failure cooperation card: patients and doctors are able to monitor changes in clinical signs (including weight), drug treatment, and baseline investigations. Patients should be encouraged to monitor their weight between clinic visits

Figure.

Exercise class for group of patients with heart failure (published with permission of participants)

Figure.

M mode echocardiogram showing left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patient (A=interventricular septum; B=posterior wall of left ventricle)

Figure.

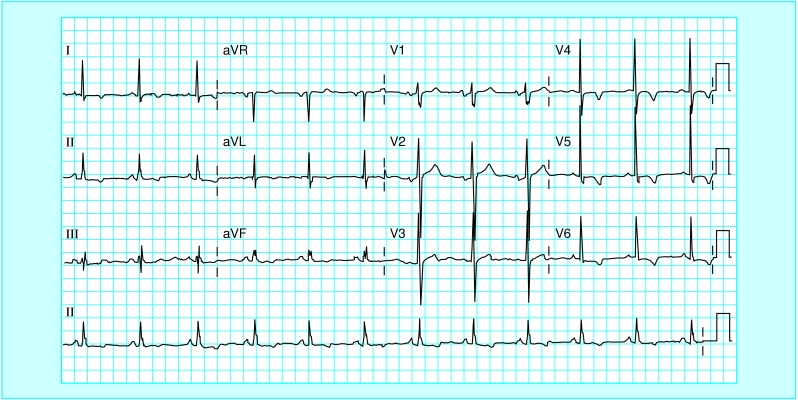

Electrocardiogram showing left ventricular hypertrophy on voltage criteria, with associated T wave and ST changes in the lateral leads (“strain pattern”)

Acknowledgments

The box about managing cachexia is based on recommendations from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (publication No 35, 1999).

Footnotes

G Jackson is consultant cardiologist in the department of cardiology, Guy's and St Thomas's Hospital, London.

The ABC of heart failure is edited by C R Gibbs, M K Davies, and G Y H Lip. CRG is research fellow and GYHL is consultant cardiologist and reader in medicine in the university department of medicine and the department of cardiology, City Hospital, Birmingham; MKD is consultant cardiologist in the department of cardiology, Selly Oak Hospital, Birmingham. The series will be published as a book in the spring.