Abstract

Background

The key correlate of protection of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) is virus neutralization, measured via sera obtained through venipuncture. Dried blood obtained with a finger prick can simplify acquisition, processing, storage, and transport in trials and thereby reduce costs. In this study, we validate an assay to measure RSV neutralization in dried capillary blood.

Methods

Functional antibodies were compared between matched serum and dried blood samples from a phase 1 trial with RSM01, an investigational anti-RSV prefusion F mAb. Hep-2 cells were infected with a serial dilution of sample-virus mixture by using RSV-A2-mKate to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration. Stability of dried blood was evaluated over time and during temperature stress.

Results

Functional antibodies in dried blood were highly correlated with serum (R2 = 0.98, P < .0001). The precision of the assay for dried blood was similar to serum. The function of mAb remained stable for 9 months at room temperature and frozen dried blood samples.

Conclusions

We demonstrated the feasibility of measuring RSV neutralization using dried blood as a patient-centered solution that may replace serology testing in trials against RSV or other viruses, such as influenza and SARS-CoV-2.

Clinical Trials Registration. NCT05118386 (ClinicalTrials.gov).

Keywords: antibodies, clinical trials, dried blood, respiratory syncytial virus, vaccine

Neutralizing antibodies against respiratory syncytial virus in serum and dried blood are highly correlated, are stable in dried blood for 6 months, and can withstand temperature variation. Dried blood samples are a patient-centered and logistical solution for clinical trials.

The respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine and monoclonal antibody (mAb) landscape has rapidly expanded with 16 candidates currently in late-phase clinical development [1]. A next-generation, long-acting mAb was approved in 2022 and expected to be commercially available in 2023 [2, 3], soon followed by vaccines for pregnant women and older adults. All late-phase vaccines are in development for high-income countries due to the high costs, so a delay in implementation is expected in areas with the highest infant RSV burden: low- and lower-middle–income countries (LMICs) [4]. RSM01 (an anti-RSV prefusion [PreF] protein site ø mAb) is intended for infants in LMICs and recently completed a phase 1a trial in healthy adults [5].

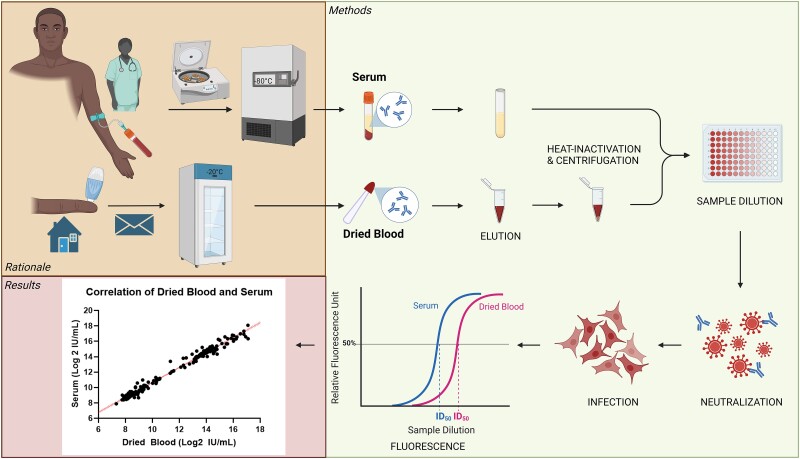

Trials largely monitor neutralizing antibody concentrations in serum as a putative correlate of protection. The functional antibodies are measured by a broad variety of neutralization assays harmonized with an international standard [6]. Blood draws are burdensome for trial participants due to the large amount of blood taken through painful venipunctures that can fail or cause a hematoma. The cost of personnel and equipment, the immediate processing, and the necessity of a −80 °C cold chain is resource intensive and complicates implementation of trials in LMICs. Moreover, venipuncture is difficult to perform in children. Alternatively, dried blood samples can simplify trials, especially in remote areas (Figure 1): 1 drop of blood is obtained with a finger or heel prick by self-sampling or minimally trained personnel. Samples can be shipped by regular mail without temperature control and stored at −20 °C before analysis, while serum samples require clotting and centrifugation before storage or analysis.

Figure 1.

Study rationale and experimental setup. Trials conventionally monitor neutralizing antibody levels in serum, which requires a professional to draw blood, immediate processing in a laboratory, and storage and transport at very low temperatures until analysis. Alternatively, dried blood samples can be obtained from a simple finger prick by either nonmedical personnel or study participants themselves. Transport through regular post and storage at room temperature or in a regular freezer reduce the necessary resources, allowing trials in remote areas. Antibody function was evaluated in dried blood vs serum on the neutralization assay. ID50, half-maximal inhibitory dilution. This figure was created with Biorender.

Dried blood with filter paper or Mitra volumetric absorptive microsamples (VAMS) is validated to measure mAb concentrations measured by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay [7], but the neutralizing capacity of antibodies after drying of blood is less well established. Five studies compared neutralizing antibodies in dried blood spots (DBSs) on filter paper or hemaPEN with plasma or serum for SARS-CoV-2, rabies, and human papilloma virus [8–12]. Samples sizes were small (range, 7–48 matched samples; total, 128 pairs) with varying correlations (R2 = 0.51–0.99). This study aimed to determine if anti-RSV antibodies retain their function in dried blood with VAMS devices in a large sample size based on clinical samples from the first-in-human trial with RSM01 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT05118386). Second, we validated the use of dried blood vs serum using a simple tool—a reporter virus–based neutralization assay—to measure neutralizing antibodies against RSV.

METHODS

Sample Handling and Preparation

Individual samples for validation of the assay were obtained from healthy adults from the University Medical Center Utrecht healthy donor service. Serum and whole blood were unaltered or spiked with RSM01, a mAb against RSV PreF site ø (Bill & Melinda Gates Medical Research Institute). After 30 minutes on a rocker to mix, Mitra 20-µL VAMS (Neoteryx Clamshell, 20004; Trajan Scientific) were touched to the whole blood sample surface to wick up the fixed volume [13] and left to dry for 3 hours at room temperature (RT). Samples were used immediately or stored at −80 °C or higher temperatures (RT or −20 °C) for stability assessments.

Clinical samples at matched time points (day 1 predose, day 91, day 151) were collected from 56 participants in clinical study GATES-MRI-RSM01-101 (NCT05118386) as follows: by venipuncture blood in serum separator tubes, which were processed to serum, or by finger prick via lancet, followed by Mitra 20-µL VAMS (Neoteryx Cartridge, 20103; Trajan Scientific) touching the blood drop to wick up the fixed volume. Of note, the adult participants in this study were expected to have preexisting RSV neutralizing antibodies from natural infection. Samples were stored at −80 °C. Prior to analysis on the neutralization assay, dried blood samples were thawed for 30 minutes before opening the air-tight bag to prevent condensation.

Dried Blood Elution for Antibody Recovery

Dried blood was rehydrated with a phosphate buffered saline (PBS)–only elution method: 1 microsampler tip was transferred to a 2-mL Eppendorf tube with 200-µL 1× PBS and incubated overnight at RT on a shaker at 300 rpm. The PBS-only elution method was compared with a validated elution method, which incubates microsampler tips in 400 µL of 1× PBS + 1% bovine serum albumin + 0.5% Tween 20 at 4 °C overnight as previously published [14]. Antibody recovery was measured on an RSV PreF enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (supplementary methods). The elimination of Tween from the elution buffer is important to enable use in cell-based assays such as this RSV neutralization assay. The elimination of bovine serum albumin from the elution buffer is important to enable use in resource-limited regions where acquisition of animal-based reagents is limited.

Percentage absolute recovery is the percentage of measured concentration divided by the spiked concentration (100 µg/mL). Percentage recovery is calculated as follows: [(measured concentrations of the spiked sample – unaltered sample) / measured concentration of the spiked standard diluent] × 100%. Elution efficiency was defined as the percentage recovery with the preferred PBS-only elution method divided by the percentage recovery with the validated elution method. Boundaries for acceptance were set at 80% to 120%.

Neutralization Assay

The neutralizing capacity of samples was tested by a neutralization assay described previously [15, 16]. Briefly, Hep-2 cells (CCL-23; ATCC) were seeded at a concentration of 0.5 × 106 cells/well in 384-well black optical bottom plates (142761; Thermo Scientific) and incubated for >4 hours. Dried blood eluate and serum were heat inactivated at 56 °C for 30 minutes. Dried blood eluate was then centrifuged at 15 000g for 10 minutes to remove cell debris. Samples were added in duplicate to dilution plates with a starting dilution of 1:5 for serum (12 µL of sample in 48 µL of medium) and 1:2 for dried blood eluate (30 µL of sample in 30 µL of medium; total 1:20 dilution after elution). Samples were serially diluted 1:3 in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (High Glucose, D6429 [Sigma]; or Glutamax, 31966-021 [Gibco]). Recombinant mKate-RSV-A2 (2.23 × 106 TCID50 [50% tissue culture infectious dose]/mL) [17, 18] was added 1:1 to the sample dilution series and incubated for 1 hour at 37 °C before addition of 50 µL of sample-virus mixture to the adherent Hep-2 cells. After 26 hours of incubation at 37 °C, we recorded relative fluorescence units with excitation at 584 nm and emission at 620 nm (FLUOstar OMEGA; BMG Labtech). The neutralization curve and 50% inhibitory concentration or dilution (IC50 or ID50, respectively) of samples were analyzed via a log (inhibitor) vs response 4-parameter nonlinear regression curve in Prism version 8.3 (GraphPad Software Inc). International units were calculated according to the manufacturer's instruction (supplementary methods), and conversion to international units obviates the need to adjust for absolute volumes.

Sample Stability

Stability of mAb in dried blood was tested with dried blood and serum samples spiked with 10 or 100 µg/mL of RSM01. Dried blood samples were stored per 2 VAMS in a generic zip-lock bag, including a generic desiccant sachet of 10 g of silica gel and humidity cards (12665157; Fisher Scientific) [19].

Long-term stability was evaluated because the opportunity to delay sample processing could ease logistical challenges of trials in remote areas. Dried blood was stored at −20 °C and RT, while serum aliquots were stored at −80 °C. Storage temperature was logged to ensure correct conditions. Samples were measured on the neutralization assay at baseline (1 day after sample preparation) and at 7 follow-up time points over 1 year. One replicate per stability sample (4 dried blood and 2 serum) was measured per time point except at baseline (n = 2). Stability was defined as <30% difference in ID50 per time point as compared with baseline ID50.

Short-term stability with a stress test was evaluated to simulate potential varying storage conditions during sample transport. Spiked dried blood samples were stored at −20 °C and underwent temperature stress at various degrees (4 °C, RT, 37 °C, or 45 °C) for a total of 48 hours before returning to −20 °C storage. Stability was defined as <30% difference in ID50 between stressed samples and samples that were not stressed but remained at −20 °C.

Statistical Analysis

Critical reagents were determined by a paired t test of linear ID50 values of the same sample measured with 2 reagents (SPSS Statistics version 26.0.0.1; IBM). Precision was calculated as the percentage coefficient of variance (% CV) of relative fluorescence units of sample duplicates (intra-assay precision) or % CV of the linear ID50 between runs (interassay precision) or between operators (interoperator precision; supplementary methods). Dried blood and serum from the RSM01 phase 1 clinical trial were compared through simple linear regression (SPSS Statistics version 26.0.0.1).

Ethical Considerations

Informed consent was obtained from healthy donors and study participants. The healthy donor service was approved by the Ethical Committee of Biobanks (study 18-774) and medical ethical committee (07-125/O). The RSM01 phase 1 clinical trial (NCT05118386) was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the US Department of Health and Human Services and the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

RESULTS

Validation of Elution Method

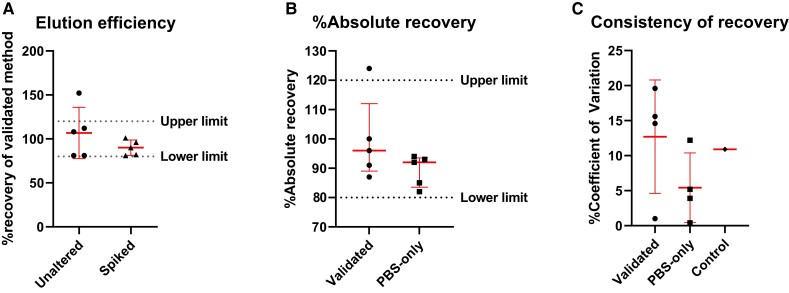

We first validated our PBS-only elution method against an existing validated elution method [14] by testing PreF binding by samples recovered from dried blood with or without spiked RSM01. Acceptance limits were met by 90% of the samples for elution efficiency and absolute recovery (Figure 2A and 2B). Comparison of elution across 2 days in the low-tech elution method showed a mean ± SD reproducibility of 5.4% ± 4.3% CV, as opposed to 12.7% ± 7.0% CV in the validated method (Figure 2C). Based on our findings, our PBS-only method was considered noninferior to the validated method for recovery of RSV PreF-binding antibody and was used for future sample processing.

Figure 2.

Comparison of 2 elution methods on dried blood samples unaltered or spiked with 100 µg/mL of RSM01 in healthy donor peripheral blood measured by RSV prefusion glycoprotein ELISA. Comparison of validated vs PBS-only elution method (5 samples from 3 healthy donors). Data are presented as mean ± SD. A, Elution efficiency was defined as the percentage recovery with the preferred PBS-only elution method divided by that with the validated elution method. B, Percentage absolute recovery per elution method. Percentage absolute recovery is the percentage of measured concentration divided by spiked concentration. Percentage recovery is calculated as follows: [(measured concentrations of the spiked sample – unaltered sample) / measured concentration of the spiked standard diluent] × 100%. C, Consistency of recovery expressed as % CV between 2 days. RSM01 (100 µg/mL) in PBS served as control. % CV is the SD divided by the mean × 100%. CV, coefficient of variance; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Validation of Dried Blood on the RSV Neutralization Assay

Validation of the RSV Neutralization Assay

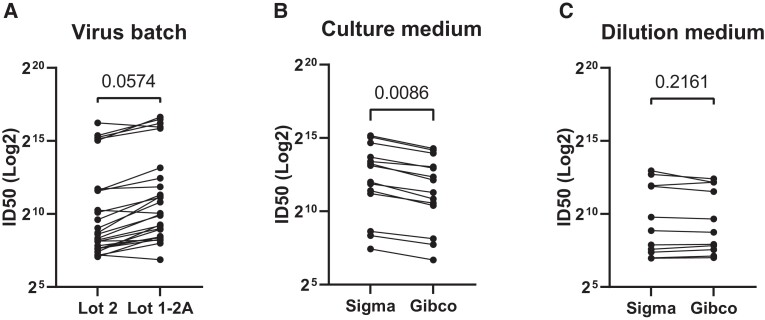

We determined the critical reagents for the RSV neutralization assay. Two virus batches cultured from the same master stock appeared to affect the ID50, but it did not achieve significance (P = .057; Figure 3A). Two brands of medium (Sigma and Gibco) for cell culture affected the ID50 of samples significantly (P = .009; Figure 3B), while it had no effect when used for the dilutions (P = .2161; Figure 3C). Based on these data, culture medium and virus batch are considered critical reagents that require characterization, while the dilution medium is not.

Figure 3.

Characterization of critical reagents for respiratory syncytial virus neutralization assay. A, Comparison of assay performance: A, with 2 virus batches; B, with 2 brands of culture medium, a critical reagent; C, with old vs new dilution medium, a noncritical reagent. Significance determined by paired t test. ID50, half-maximal inhibitory dilution.

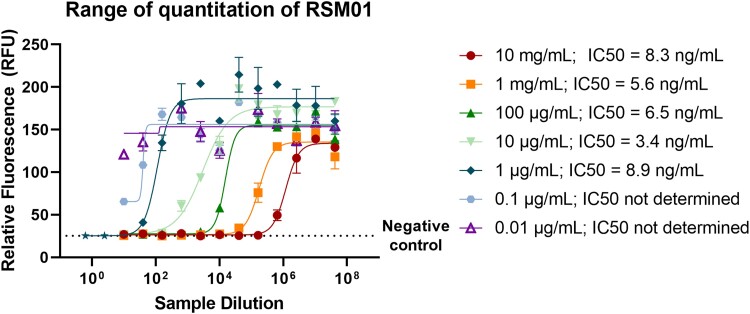

A range of concentrations of RSM01 in PBS was evaluated to determine the limits of detection on the neutralization assay. We found a wide dynamic range of the assay, enabling measurement of RSM01 in concentrations ranging from 1 µg/mL up to >10 mg/mL (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Characterization of limits of detection of respiratory syncytial virus neutralization assay. Dynamic range of quantitation of RSM01 antibodies in PBS on the neutralization assay. A range of concentrations of RSM01 in PBS (0.01 µg/mL–10 mg/mL) with equal dilution series (1:5 starting dilution, 4-fold serial dilutions) was measured to obtain IC50 values. Error bars resemble technical duplicates. The lowest 2 concentrations did not qualify the assay quality control criteria, and IC50 values could not be determined. IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Precision of the RSV neutralization assay with dried blood (≤28.1% CV) was noninferior to serum samples (≤34.0% CV) for spiked (1–100 µg/mL) or unaltered samples (Supplementary Table 1). Interoperator variation was lower than interassay variation for all sample types except spiked serum.

Stability of Dried Blood

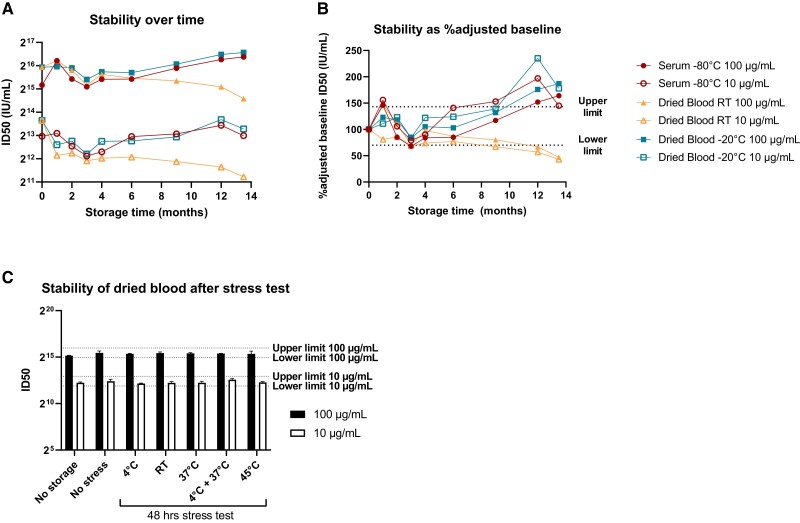

We evaluated long-term storage of dried blood samples vs serum at RT and −20 °C. Dried blood with 100-µg/mL (high) or 10-µg/mL (low) concentrations of RSM01 retain stable functionality when compared with serum (Figure 5A). An outlier of serum (100 µg/mL) at 1-month storage is likely an artifact due to faulty measurement (as this is unlikely to be an increase in concentration and because subsequent points show stability). What appears as a loss of neutralizing capacity after 1-month storage could also be caused by faulty baseline measurement. Therefore, we calculated an adjusted baseline using all available data of heathy donor samples spiked with 100 µg/mL of RSM01 (n = 18 of 3 healthy donors) or 10 µg/mL (n = 11 of 2 healthy donors), as natural immunity is negligible when spiked with these concentrations of RSM01. Antibodies at higher concentrations retain their function for 9 months in frozen and RT dried blood as well as in frozen serum, but at lower concentrations, the loss of mAb function is already observed after 6 months of storage (Figure 5B). Long-term storage (>6 months) of dried blood at RT showed discoloration that increased over time from maroon to brown-gray. Humidity was <10% over time in dried blood samples at either storage condition.

Figure 5.

Stability of antibody function in dried blood vs serum samples. Stability of functional antibodies in dried blood stored at room temperature and −20 °C vs serum at −80 °C (baseline, n = 2; other time points, n = 1). Preset upper and lower limits of acceptance are 143% and 70%, respectively (dotted lines). A, Neutralizing capacity after long-term storage. B, Neutralizing capacity of dried blood expressed as the percentage of adjusted baseline neutralizing capacity. Adjusted baseline was calculated as the geometric mean titer of all available data of healthy donor blood spiked with 100 µg/mL (n = 18) or 10 µg/mL (n = 11), excluding the long-term stability data. C, Dried blood sample stability after short-term storage at −20 °C with 48-hour stress test at various temperatures before returning to storage at −20 °C. Upper and lower limits of acceptance are based on stable storage at −20 °C (no-stress condition). ID50, half-maximal inhibitory dilution; RT, room temperature.

Short-term storage at −20 °C followed by 48 hours of temperature stress did not induce sample instability at either spiked concentration (Figure 5D). Dried blood samples were kept at humidity <10% throughout the temperature stress, and the samples at higher temperatures (>37 °C) showed brown-gray discoloration similar to that observed at >6-month storage at RT.

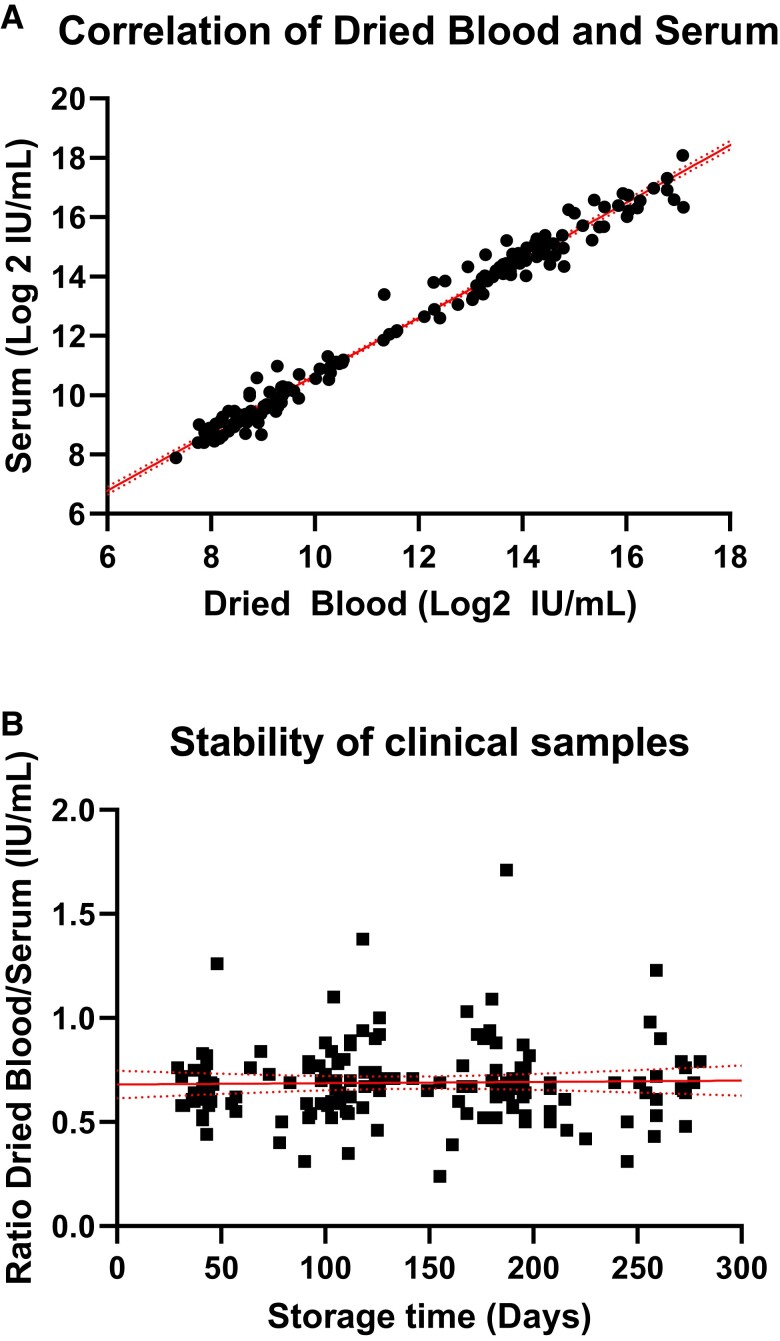

Comparison of Functional Antibodies in Dried Blood and Serum on the RSV Neutralization Assay

We compared the neutralizing activity in dried blood eluate against serum at 3 time points for 56 participants of a phase 1 clinical trial evaluating RMS01 in healthy adults. Neutralizing activity in dried blood samples correlated strongly with serum neutralization (R2 = 0.98, P < .0001, n = 165 matched samples; Figure 6A). The duration of storage between sample collection and measurement did not have an effect on the ratio between the matched dried blood and serum samples (slope ≍ 0; mean ratio, 0.69; 95% CI, .66–.72), with a storage time of 29 to 280 days (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Antibody function in dried blood samples vs serum samples. A, Simple linear regression of log2 ID50 values of RSM01 phase 1 clinical trial serum and dried blood samples at 3 time points (R2 = 0.981, n = 165 matched samples) with 95% CI (dotted lines). B, Simple linear regression of the ratio between dried blood and serum ID50 (R2 < 0.001, slope ≍ 0) with 95% CI (dotted lines). ID50, half-maximal inhibitory dilution.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show for the first time that antibodies stored in dried blood retain their neutralizing capacity against RSV, and we validated an RSV neutralization assay for reconstituted dried blood. The strong correlation between the sample types collected in a clinical trial (R2 = 0.98) indicates that dried blood could be used to measure RSV neutralizing antibodies. Dried blood samples are highly stable as compared with serum, for at least 9 months of storage at −20 °C and 6 months at RT. Short-term temperature stress did not induce instability.

This study is the first to use dried blood samples to measure anti-RSV antibody function. To date, antibody concentration, not function, has repeatedly been studied in dried blood. The concentrations of therapeutic mAbs are reliably recovered from VAMS [7]. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers in VAMS highly correlate with serum, suggesting that VAMS are a valid method to evaluate antibody titers [14, 20]. The varying correlation and precision in previous head-to-head comparisons of neutralizing antibodies [8–12] with DBS on filter paper instead of VAMS could be explained by the smaller sample sizes or by the hematocrit effect. This effect is a well-known limitation of DBS where the hematocrit-dependent blood flow through the paper complicates reproducible recovery of the serum fraction containing the antibodies of interest when a fixed area of the card is punched [21]. VAMS circumvent these limitations by ensuring homogenous sample uptake, and the entire sample is eluted, allowing more consistent recovery [21]. Moreover, the volume taken up from a test tube or finger prick is adequately consistent: 107% ± 3.4% of the reported blood volume when taken from a test tube and 102% ± 6.1% when taken from a finger prick [7]. Other devices that control total volume are anticipated to have acceptable precision similar to that shown here with VAMS.

Antibody function is widely assumed to be stable over time in serum, but it is less known if the assumption holds for dried blood. According to a systematic review, DBSs are most stable with the least variation at −20 °C and −70 °C regardless of the intended measurements [22]. No clear decrease in mAb concentration is observed in VAMS up to 1-month storage at RT and 4 °C [7], and HIV antibodies are stable when stored for 6 weeks at 4 °C, −20 °C, or −70 °C in DBS [23]. We showed that functional antibody in dried blood stored at RT and −20 °C is stable as compared with the adjusted baseline up to at least 6 months of storage. However, the neutralizing capacity drops between baseline and month 1 raw data (Figure 5A). We believe that limitations of our study design underestimate stability when compared with a single baseline measurement at T = 0, which was unexpectedly high. Therefore, we calculated a theoretical baseline using various healthy donors to correct this limitation. After short-term storage in the stress test, no loss in neutralizing capacity was observed, supporting the potential faulty baseline measurement in the long-term stability test (Figure 5C). Moreover, the neutralizing capacity of dried blood samples plateaus between months 1 and 9 (Figure 5A); therefore, the samples are most likely stable. The reason for the upward trend observed for frozen serum and frozen dried blood is unknown. One possibility is that aggregates formed during long-term frozen storage may better neutralize RSV, which was observed for another mAb [24, 25]. Although adding Tween 20 to the extraction buffer could disrupt aggregates, this hypothesis was not directly tested, as detergent is inconsistent with the cell-based assay. We observe that 48 hours of temperature variation—for example, during shipments of samples—is acceptable in terms of sample stability, although, like neutralizing capacity, immunoglobulin G concentration in DBS on filter paper was shown to decrease drastically after 7 days of storage at 45 °C [26]. Our data suggest that −20 °C is more suitable for storage >6 months, but shorter storage is also acceptable at RT. These findings need to be confirmed in repeat experiments.

This study has several strengths and limitations. The neutralization assay is sensitive to several reagents due to the live cells and virus, which showcases the importance of same batch measurements and the use of assay controls. The enrichment of the media source might affect viral infection and/or replication and thus influence the readout. The in-house controls allowed for conversion of the results to international units to compare with other RSV neutralization data worldwide and correct for batch variations during long studies. As the hematocrit fraction is removed during serum processing, the mAb concentration in serum is higher than it is in the capillary blood and thus in the dried blood samples. The normal hematocrit is 40% to 54% for men and 36% to 48% for women [27], so the serum is expected to be 1.56 to 2.17 times more concentrated than dried blood. The ratio of dried blood to serum is therefore naturally expected to vary between 0.46 and 0.64, which we consider to be similar to the ratio of 0.69 (95% CI, 0.66–0.72) between dried blood and serum. Another limitation is that we validated the assay on dried blood only from healthy adults. Considering the intended use in infants—with maturing immune systems and possibly with comorbidities—we need to continue validation on blood from healthy infants and those with comorbidities such as prematurity, coinfection, or immune deficiencies. The scope of this study did not include isotypes of antibodies other than immunoglobulin G, so it remains unknown if dried blood is a valid sampling method for studying immunoglobulins M, A, or E. Last, as assay precision did not meet the 30% CV target for serum samples, it suggests that the ±30% target may have been overly conservative for a bioassay with 2 living components: cells and virus.

We demonstrated RSV neutralization on dried blood as a patient-centered solution that may replace serology testing in trials in LMICs and potentially be used as a tool to monitor protection against RSV globally. Our study has implications for the future of vaccine and mAb development against RSV and other respiratory viruses, such as influenza and SARS-CoV-2, as blood draws can be challenging in remote areas, especially in young children. One obstacle for worldwide vaccine and mAb access is globally representative trials that need to take place in countries with the highest disease burden because efficacy can differ among regions [28]. The potential to use dried blood obtained with a simple finger prick can reduce logistical burden of trained phlebotomists and cold chain requirements and thereby reduce cost and complexity. We plan to validate the assay in an LMIC setting as proof of concept that sample analysis is independent of an advanced immunology laboratory in a high-income country.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Jonne Terstappen, Department of Pediatric Infectious Diseases and Immunology, Wilhelmina Children's Hospital, University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands; Center for Translational Immunology, University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Eveline M Delemarre, Center for Translational Immunology, University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Anouk Versnel, Center for Translational Immunology, University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Joleen T White, Bioassay Development and Operations, Bill & Melinda Gates Medical Research Institute, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Alexandrine Derrien-Colemyn, Vaccine Research Center, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Tracy J Ruckwardt, Vaccine Research Center, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Louis J Bont, Department of Pediatric Infectious Diseases and Immunology, Wilhelmina Children's Hospital, University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands; Center for Translational Immunology, University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Netherlands; Respiratory Syncytial Virus Network Foundation, Zeist.

Natalie I Mazur, Department of Pediatric Infectious Diseases and Immunology, Wilhelmina Children's Hospital, University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands; Center for Translational Immunology, University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Netherlands; Department of Pediatrics, St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, Netherlands.

Notes

Author contributions. J. T., J. T. W., L. J. B., and NIM were involved in the design and plan for this study. J. T., E. M. D., and A. V. were involved in the data collection and analysis. T. J. R. and A. D.-C. offered methodology transfer, materials, and support during study conduction. J. T., L. J. B., and N. I. M. were involved with quality assessment and contributed to writing the manuscript in collaboration with all coauthors.

Data availability. Clinical data not publicly available. On reasonable request to the corresponding author, the validation data can be shared.

Disclaimer. Under the grant conditions of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the author accepted manuscript version that might arise from this submission.

Financial support. This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (grant INV-008522). Funding to pay the Open Access Publication was provided by the Consortium Current Content Agreement between Oxford University Press and the Association of Universities of the Netherlands.

References

- 1. Mazur NI, Terstappen J, Baral R, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus prevention within reach: the vaccine and monoclonal antibody landscape. Lancet Infect Dis 2023; 23: e2–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Griffin MP, Yuan Y, Takas T, et al. Single-dose nirsevimab for prevention of RSV in preterm infants. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:415–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hammitt LL, Dagan R, Yuan Y, et al. Nirsevimab for prevention of RSV in healthy late-preterm and term infants. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:837–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li Y, Wang X, Blau DM, et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022; 399:2047–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ananworanich J, Heaton PM. Bringing preventive RSV monoclonal antibodies to infants in low- and middle-income countries: challenges and opportunities. Vaccines 2021; 9:961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raghunandan R, Higgins D, Hosken N. RSV neutralization assays—use in immune response assessment. Vaccine 2021; 39:4591–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bloem K, Schaap T, Boshuizen R, et al. Capillary blood microsampling to determine serum biopharmaceutical concentration: Mitra microsampler vs dried blood spot. Bioanalysis 2018; 10:815–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Itell HL, Weight H, Fish CS, et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody binding and neutralization in dried blood spot eluates and paired plasma. Microbiol Spectr 2021; 9:e0129821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Louie KS, Dalel J, Reuter C, et al. Evaluation of dried blood spots and oral fluids as alternatives to serum for human papillomavirus antibody surveillance. mSphere 2018; 3:e00043-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maritz L, Woudberg NJ, Bennett AC, et al. Validation of high-throughput, semiquantitative solid-phase SARS coronavirus-2 serology assays in serum and dried blood spot matrices. Bioanalysis 2021; 13:1183–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sancilio AE, D’Aquila RT, McNally EM, et al. A surrogate virus neutralization test to quantify antibody-mediated inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 in finger stick dried blood spot samples. Sci Rep 2021; 11:15321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Doornekamp L, Embregts CWE, Aron GI, et al. Dried blood spot cards: a reliable sampling method to detect human antibodies against rabies virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020; 14:e0008784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Protti M, Mandrioli R, Mercolini L. Tutorial: volumetric absorptive microsampling (VAMS). Anal Chim Acta 2019; 1046:32–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Klumpp-Thomas C, Kalish H, Drew M, et al. Standardization of ELISA protocols for serosurveys of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic using clinical and at-home blood sampling. Nat Commun 2021; 12:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Phung E, Chang LA, Morabito KM, et al. Epitope-specific serological assays for RSV: conformation matters. Vaccines (Basel) 2019; 7:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ngwuta JO, Chen M, Modjarrad K, et al. Prefusion F-specific antibodies determine the magnitude of RSV neutralizing activity in human sera. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7:309ra162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hotard AL, Shaikh FY, Lee S, et al. A stabilized respiratory syncytial virus reverse genetics system amenable to recombination-mediated mutagenesis. Virology 2012; 434:129–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stobart CC, Hotard AL, Meng J, Moore ML. BAC-based recovery of recombinant respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Methods Mol Biol 2017; 1602:111–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van de Merbel N, Savoie N, Yadav M, et al. Stability: recommendation for best practices and harmonization from the global bioanalysis consortium harmonization team. AAPS J 2014; 16:392–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whitcombe AL, McGregor R, Craigie A, et al. Comprehensive analysis of SARS-CoV-2 antibody dynamics in New Zealand. Clin Transl Immunol 2021; 10:e1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Velghe S, Delahaye L, Stove CP. Is the hematocrit still an issue in quantitative dried blood spot analysis? J Pharm Biomed Anal 2019; 163:188–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Amini F, Auma E, Hsia Y, et al. Reliability of dried blood spot (DBS) cards in antibody measurement: a systematic review. PLoS One 2021; 16:e0248218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Castro AC, Borges LG, Souza Rda S, Grudzinski M, D’Azevedo PA. Evaluation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and 2 antibodies detection in dried whole blood spots (DBS) samples. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2008; 50:151–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Le Basle Y, Chennell P, Tokhadze N, Astier A, Sautou V. Physicochemical stability of monoclonal antibodies: a review. J Pharm Sci 2020; 109:169–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ma H, Ó’Fágáin C, O’Kennedy R. Antibody stability: a key to performance—analysis, influences and improvement. Biochimie 2020; 177:213–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kaduskar O, Bhatt V, Prosperi C, et al. Optimization and stability testing of four commercially available dried blood spot devices for estimating measles and rubella IgG antibodies. mSphere 2021; 6:e0049021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Billett HH. Hemoglobin and hematocrit. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, eds. Clinical methods: the history, physical, and laboratory examinations. 3rd ed. Boston: Butterworths, 1990:chap 151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Madhi SA, Polack FP, Piedra PA, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus vaccination during pregnancy and effects in infants. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:426–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.