A new polyunsaturated margarine with added plant stanols, Benecol, was introduced in several European countries last year, and a similar margarine with added plant sterols will be introduced under the Flora label later this year. These products lower serum concentrations of cholesterol, but they are expensive.1–14 In Great Britain the cost is about £2.50 ($4.00) for a 250 g tub compared with 60p for ordinary polyunsaturated margarine and 90p for butter. This article considers quantitatively the health aspects of adding plant sterols and stanols to margarines and other foods.

Summary points

Plant sterols and stanols reduce the absorption of cholesterol from the gut and so lower serum concentrations of cholesterol

Plant sterols or stanols that have been esterified to increase their lipid solubility can be incorporated into foods

The 2 g of plant sterol or stanol added to an average daily portion of margarine reduces serum concentrations of low density lipoprotein cholesterol by an average of 0.54 mmol/l in people aged 50-59, 0.43 mmol/l in those aged 40-49, and 0.33 mmol/l in those aged 30-39

A reduction in the risk of heart disease of about 25% would be expected for this reduction in low density lipoprotein cholesterol; this is larger than the effect that could be expected to be achieved by people reducing their intake of saturated fat

The added costs of £70 per person per year will limit consumption; however, if stanols and sterols become cheaper, their introduction into the food chain will make them an important innovation in the primary prevention of heart disease

Methods

Randomised trials included in this review were identified by a Medline search using the term “plant sterols.” Additional trials were identified from citations in these papers and in review articles. Other trials in children with familial hypercholesterolaemia were not included.

Plant sterols and stanols

Sterols are an essential component of cell membranes, and both animals and plants produce them. The sterol ring is common to all sterols; the differences are in the side chain. Cholesterol is exclusively an animal sterol. Over 40 plant sterols (or phytosterols) have been identified but β-sitosterol (especially), campesterol, and stigmasterol are the most abundant. These three sterols are structurally similar to cholesterol: they are all 4-desmethyl sterols (containing no methyl groups at carbon atom 4).

Stanols are saturated sterols (they have no double bonds in the sterol ring). Stanols are less abundant in nature than sterols. Plant stanols are produced by hydrogenating sterols. The term sterol is sometimes used as a generic term to include unsaturated sterols and saturated stanols, but it is used here to refer specifically to the unsaturated compounds.

It was recognised in the 1950s that plant sterols lower serum concentrations of cholesterol15; they do this by reducing the absorption of cholesterol from the gut by competing for the limited space for cholesterol in mixed micelles (the “packages” in the intestinal lumen that deliver mixtures of lipids for absorption into the mucosal cells).6,11,16–18 In Europe the average consumption of butter or margarine is 25 g per person each day, and the fortified margarines contain 2 g of plant sterols or stanols per daily portion. About 0.25 g of plant sterols and 0.3 g of cholesterol occur naturally in the daily diet; the amount of plant sterols consumed daily is twice as high in a vegetarian diet. The added plant sterols or stanols in fortified margarine reduce the absorption of cholesterol in the gut—both dietary and endogenous (that is, excreted in bile)—by about half, from the normal proportion of about half the total cholesterol to one quarter. This reduced absorption lowers serum cholesterol despite the compensatory increase in cholesterol synthesis which occurs in the liver and other tissues.6,11 Plant sterols are potentially atherogenic like cholesterol19 but atherogenesis does not occur because so little of the plant sterols are absorbed (for example, about 5% of β-sitosterol, 15% of campesterol, and less than 1% of dietary stanols are absorbed).16 The use of plant sterols as cholesterol lowering drugs has been limited: initially the market was small and later the greater efficacy of statins was evident. By the 1980s, however, it was recognised that as naturally occurring substances plant sterols and stanols could be added to foods. Because fats are needed to solubilise sterols, margarines are an ideal vehicle for them, although cream cheese, salad dressing, and yoghurt are also used. Esterification of the plant sterols and stanols with long chain fatty acids increases their lipid solubility and facilitates their incorporation into these foods. Benecol was the first fortified margarine, and stanols were added because the evidence suggested that they had greater potential to lower cholesterol than sterols and the amount absorbed from the gut is negligible.16,18,20,21

Benefits of plant sterols and stanols

The table summarises the results of randomised double blind trials in adults that compared the ability of polyunsaturated margarines with and without added plant sterols to lower cholesterol. The effect of selection for comparatively high concentrations of serum cholesterol in some trials was modest and, with the exception of one small trial,13 mean serum concentrations of low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in the control groups ranged from 3.0 mmol/l to 4.5 mmol/l (median 3.8 mmol/l), close to the age-specific mean found in the Western world. The randomised comparisons in three trials suggested that there was little difference in the extent to which sterols or stanols lower cholesterol concentrations (although the confidence intervals are consistent with the evidence above that stanols are better).1,12,14 The table shows the reduction in LDL cholesterol in each trial; the reductions in total cholesterol concentrations were similar and there was little change in serum concentrations of high density lipoprotein cholesterol or triglyceride.

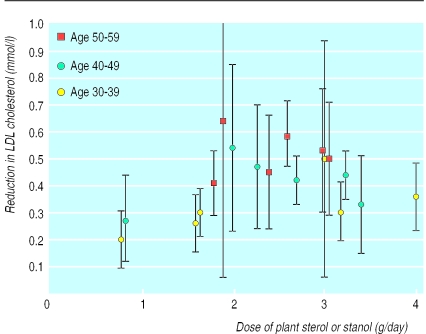

The figure shows the reduction in concentration of LDL cholesterol achieved in each trial and the dose of plant sterol or stanol. The reduction in the concentration of LDL cholesterol at each dose is significantly greater in older people than in younger people. The dose-response relation is continuous up to a dose of about 2 g of plant sterol or stanol per day. At higher doses no further reduction in LDL cholesterol is apparent, confirming the evidence of a plateau identified by earlier non-randomised studies.17 At doses of ⩾2 g per day the average reduction in serum LDL cholesterol was 0.54 mmol/l (14%; 95% confidence interval 0.46 to 0.63 mmol/l) for participants aged 50-59,3,6,8,11 0.43 mmol/l (9%; 0.37 to 0.47 mmol/l) in participants aged 40-49,1,4,5,13 and 0.33 mmol/l (11%; 0.25 to 0.40 mmol/l) for those aged 30-391,2,5,10; this trend was statistically significant (P=0.005). At a dose of 2 g per day (the amount added to an average daily portion of fortified margarine) the reduction in LDL cholesterol is likely to be at least 0.5 mmol/l for those aged 50-59 and 0.4 mmol/l for those aged 40-49.

Data from observational studies and randomised trials indicate that in people aged 50-59 the reduction in LDL cholesterol of about 0.5 mmol/l would reduce the risk of heart disease by about 25% after about two years.22 In younger people the proportionate reduction in risk would be similar (the reduction in cholesterol concentrations is smaller but the association between cholesterol and heart disease is stronger).22 Trials of six different interventions to lower serum cholesterol have all found a reduction in the incidence of heart disease (these interventions include four pharmacologically unrelated drugs, a reduction in dietary saturated fat, and ileal bypass surgery).22,23 Nothing except a reduction in cholesterol is common to the six interventions, and for each intervention the proportionate reduction in mortality from heart disease is commensurate with the reduction in cholesterol concentration.17,18 Margarines with plant sterols or stanols thus reduce the risk of heart disease by one quarter: this is the reduction expected from the decrease in serum cholesterol.

This is an impressive result for a dietary change that, price apart, is modest. It is larger than the effect that could be expected to occur if people ate less animal fat, and it is all the more impressive in light of the fact that despite the extensive promotion of healthy eating there has been little reduction in average serum cholesterol concentrations in many countries. Recent surveys in England found that mean cholesterol concentrations are only 1-2% lower than those of 25 years ago.24,25 For a person replacing butter with a plant sterol margarine the reduction in cholesterol would be even greater. Replacing butter with ordinary polyunsaturated margarines lowers total serum and LDL cholesterol by about 0.3 mmol/l,26,27 so the overall reduction would be about 0.7 mmol/l, or as much as any cholesterol lowering drug except statins.

Efficacy in combination with low fat diets

One non-randomised study found only a small average reduction in LDL cholesterol concentrations (0.16 mmol/l) despite participants taking 3 g of plant stanols daily.28 The participants were on a low fat and low cholesterol diet, and the result was interpreted as suggesting that plant sterols are ineffective when dietary fat, dietary cholesterol, or LDL cholesterol concentrations are low. This is unlikely. In two recent randomised trials of stanol margarines in which participants were on low fat, low cholesterol diets, the reductions in serum concentrations of LDL cholesterol were similar to those found in other trials in which the intake of dietary fat was higher.4,9 Plant stanols were equally effective in patients taking statins who had mean LDL cholesterol concentrations of only 2.9 mmol/l.6 Other explanations for the discrepancy are more plausible: chance (at the upper confidence interval of the result, an LDL cholesterol reduction of 0.43 mmol/l is what might be expected) or the fact that the stanol was administered in capsules and not esterified and blended into the fat of a meal. (Sterols administered in capsules may not disperse fully or dissolve in the gut, limiting their ability to reduce the absorption of cholesterol.9)

Safety

The most important concern about plant sterols is that they reduce the absorption of some fat soluble vitamins. Randomised trials have shown that plant sterols and stanols lower blood concentrations of β carotene by about 25%, concentrations of α carotene by 10%, and concentrations of vitamin E by 8%.1,2,8,29 Since these vitamins protect LDL cholesterol from oxidation, and sterols and stanols reduce the amount of LDL cholesterol, the changes in blood concentrations of the vitamins were adjusted in the trials for the lower concentrations of LDL cholesterol. With this adjustment concentrations of vitamin E were not lower but concentrations of β carotene were reduced by between 8% and 19%.1,2,8,29 There was no benefit to increasing the blood concentrations of β carotene and vitamin E by greater proportions than these,30,31 although we do not know whether this is the case for other carotenes. Eating more fruit and vegetables would counter the decrease in absorption. The blood concentration of vitamin D is unaffected.2,8 No other side effects or biochemical anomalies were evident in the randomised trials of plant sterol or stanol margarines (one of which lasted a year3), in earlier studies testing doses as high as 3 g/day for three years, or in animal studies testing proportionately higher doses.16,17,32 Stanol margarines have been sold in Finland for three years without evidence of hazard, and a tenth of the amount of plant sterols found in these margarines occurs naturally in a normal diet. Plant sterols or stanols do not adversely affect the taste or consistency of margarines.3,10

The place of sterol and stanol margarines in the diet

The excess cost per person of margarines containing added plant sterols or stanols is about 20p per day or £70 per year. Affluent people may willingly pay this to reduce their risk of death from heart disease by a quarter but poorer people, who are at higher risk of heart disease, will tend to be dissuaded from buying the product. The cost reflects the large amount of raw material needed (about 2500 parts to extract one part sterol). Moreover, supplies are limited. The present sources—extracted from a byproduct in the refining of vegetable oils or from the oil obtained from pinewood pulp in papermaking—can supply only about 10% of the people in the West. In the foreseeable future, the product will be used only by a minority of people. However, in many countries there is also a legal obstacle: no health claim can be made in the advertising of these margarines because they are a food, not a drug. More people might buy the product if they were aware of the size of the health benefit.

Plant sterol and stanol margarines may appeal to patients with ischaemic heart disease but they should not replace statins because the reduction in the concentration of LDL cholesterol is greater with statins. Both could be taken together however, since the cholesterol lowering effects of the two are additive.6 The overall costs of the two are equivalent: statins cost about three times as much as plant sterol margarines but they lower serum cholesterol by three times as much.

In the longer term, the addition of plant sterols and stanols to foods could be an important public health policy if new technology and economies of scale can lower the cost and enable a greater demand to be met. The serum cholesterol of the average older adult in Western countries is high (6.0 to 6.5 mmol/l),24 with a correspondingly high lifetime risk of death from heart disease (about 25%). Introducing plant sterols into the food chain would lower the average serum cholesterol concentration in Western countries, with the added advantage of “demedicalising” the reduction (that is, one would not have to become a patient to benefit). There is a precedent for such fortification: in the United States folic acid has been added to flour since 1997. In addition to the expected reduction in the incidence of neural tube defects, there has also been a significant reduction in the average serum concentration of homocysteine,33 which is likely to reduce mortality from heart disease.

The launch of margarines containing plant sterols and stanols is a welcome first step in what may become an important innovation in the primary prevention of ischaemic heart disease. It is to be hoped that in the longer term plant sterols and stanols will become cheap and plentiful and so will be able to be added to foods eaten by the majority of the population.

Table.

Randomised double blind trials that reported the difference in serum cholesterol obtained from using polyunsaturated margarines with and without added plant sterols or stanols. Trials were parallel group trials unless indicated otherwise

| Trial (place) | No of participants in treatment group/placebo group | Mean age (years) | Duration of trial (weeks) | Type | Average daily dose (g) | Placebo adjusted reduction in serum low density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Westrate et al1 (Netherlands) | 80* | 45 | 3.5 | Stanol | 2.7 | 0.42 (0.33 to 0.51) |

| Sterol | 3.2 | 0.44 (0.35 to 0.53) | ||||

| Hendriks et al2 (Netherlands) | 80* | 37 | 3.5 | Sterol | 0.8 | 0.20 (0.10 to 0.31) |

| Sterol | 1.6 | 0.26 (0.15 to 0.36) | ||||

| Sterol | 3.2 | 0.30 (0.20 to 0.41) | ||||

| Miettinen et al3 (Helsinki) | 51/51 | 50 | 52 | Stanol | 1.8 | 0.41 (0.29 to 0.53) |

| 51/51 | Stanol | 2.6 | 0.59 (0.47 to 0.71) | |||

| Hallikainen et al4 (Finland) | 38/17 | 43 | 8 | Stanol | 2.3 | 0.47 (0.24 to 0.70) |

| Vanhanen et al5 (Helsinki) | 34/33 | 46 | 6 | Stanol | 3.4† | 0.33 (0.15 to 0.51) |

| Gylling et al6 (Helsinki) | 22* | 51 | 7 | Stanol | 3.0 | 0.53 (0.30 to 0.76) |

| Jones et al7 (Montreal) | 22* | 35 | 1.4 | Sterol | 1.7‡ | 0.30 (0.21 to 0.39) |

| Gylling et al8 (Helsinki) | 21* | 53 | 5 | Stanol | 2.4§ | 0.45 (0.24 to 0.66) |

| Jones et al9 (Montreal) | 16/16 | about 50 | 4 | Stanol | 1.9 | 0.64 (0.06 to 1.22) |

| Niinikoski et al10 (Finland) | 12/12 | 37 | 5 | Stanol | 3.0 | 0.50 (0.06 to 0.94) |

| Gylling et al11 (Helsinki) | 11* | 58 | 6 | Stanol | 3.0 | 0.50 (0.29 to 0.71) |

| Miettinen et al12 (Helsinki) | 9/8 | 45 | 9 | Stanol | 1.0† | 0.28 (0.01 to 0.55)¶ |

| 7/8 | Sterol | 0.8† | 0.26 (−0.05 to 0.57)¶ | |||

| Vanhanen et al13 (Helsinki) | 7/8 | 47 | 6 | Stanol | 0.8† | 0.28 (0.0 to 0.56)¶ |

| 7/8 | Stanol | 2.0† | 0.54 (0.23 to 0.85) | |||

| Plat et al14 (Netherlands) | 70/42 | 33 | 8 | Stanol | 4.0 | 0.36 (0.23 to 0.49) |

Crossover trial. †In mayonnaise. ‡In olive oil. §In butter. ¶Data from these small trials which tested low doses are combined in the figure.

Figure.

Results of randomised double blind trials of margarines with and without added plant sterols or stanols showing the reduction in serum concentrations of low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol (95% confidence intervals) plotted against the daily dose. The data are from the table

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Westtrate JA, Meijer GW. Plant sterol-enriched margarines and reduction of plasma total- and LDL-cholesterol concentrations in normocholesterolaemic and mildly hypercholesterolaemic subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52:334–343. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hendriks HFJ, Westrate JA, van Vliet T, Meijer GW. Spreads enriched with three different levels of vegetable oil sterols and the degree of cholesterol lowering in normocholesterolaemic and mildly hypercholesterolaemic subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53:319–327. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miettinen TA, Puska P, Gylling H, Vanhanen H, Vartianen E. Reduction of serum cholesterol with sitostanol-ester margarine in a mildly hypercholesterolemic population. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1308–1312. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallikainen MA, Uusitupa MI. Effects of 2 low-fat stanol ester-containing margarines on serum cholesterol concentrations as part of a low-fat diet in hypercholesterolemic subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:403–410. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanhanen HT, Blomqvist S, Ehnholm C, Hyvönen M, Jauhiainen M, Torstila I, et al. Serum cholesterol, cholesterol precursors, and plant sterols in hypercholesterolemic subjects with different apoE phenotypes during dietary sitostanol ester treatment. J Lipid Res. 1993;34:1535–1543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gylling H, Radhakrishnan R, Miettinen TA. Reduction of serum cholesterol in postmenopausal women with previous myocardial infarction and cholesterol malabsorption induced by dietary sitostanol ester margarine. Circulation. 1997;96:4226–4231. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.12.4226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones PHJ, Howell T, MacDougall DE, Feng JY, Parsons W. Short-term administration of tall oil phytosterols improves plasma lipid profiles in subjects with different cholesterol levels. Metabolism. 1998;47:751–756. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(98)90041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gylling H, Miettinen TA. Cholesterol reduction by different plant stanol mixtures and with variable fat intake. Metabolism. 1999;48:575–580. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones PJH, Ntanios FY, Raeini-Sarjaz MR, Vanstone CA. Cholesterol-lowering efficacy of a sitostanol-containing phytosterol mixture with a prudent diet in hyperlipidemic men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:1144–1150. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.6.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niinikoski H, Viikari J, Palmu T. Cholesterol-lowering effect and sensory properties of sitostanol ester margarine in normocholesterolemic adults. Scand J Nutr. 1997;41:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gylling H, Miettinen TA. Serum cholesterol and cholesterol and lipoprotein metabolism in hypercholesterolaemic NIDDM patients before and during sitostanol ester-margarine treatment. Diabetologia. 1994;37:773–780. doi: 10.1007/BF00404334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miettinen TA, Vanhanen H. Dietary sitostanol related to absorption, synthesis and serum level of cholesterol in different apolipoprotein E phenotypes. Atherosclerosis. 1994;105:217–226. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanhanen HT, Kajander J, Lehtovirta H, Miettinen TA. Serum levels, absorption efficiency, faecal elimination and synthesis of cholesterol during increasing doses of dietary sitostanol esters in hypercholesterolaemic subjects. Clin Sci (Colch) 1994;87:61–67. doi: 10.1042/cs0870061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plat J, Mensink RP. Vegetable oil versus wood based stanol ester mixtures: effects on serum lipids and hemostatic factors in non-hypercholesterolemic subjects. Atherosclerosis. 2000;148:101–112. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00261-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Best MM, Duncan CH, Van Loon EJ, Wathen JD. Lowering of serum cholesterol by the administration of a plant sterol. Circulation. 1954;10:201–206. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.10.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones PJH, MacDougall DE, Ntanios F, Vanstone CA. Dietary phytosterols as cholesterol-lowering agents in humans. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;75:217–227. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-75-3-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lees AM, Mok HYI, Lees RS, McCluskey MA, Grundy SM. Plant sterols as cholesterol-lowering agents: clinical trials in patients with hypercholesterolemia and studies of sterol balance. Atherosclerosis. 1977;28:325–338. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(77)90180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinemann T, Kullak-Ublick A, Pietruck B, von Bergmann K. Mechanisms of action of plant sterols on inhibition of cholesterol absorption. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;40(suppl 1):59–63S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glueck CJ, Speirs J, Tracy T, Streicher P, Illig E, Vandegrift J. Relationships of serum plant sterols (phytosterols) and cholesterol in 595 hypercholesterolemic subjects, and familial aggregation of phytosterols, cholesterol, and premature coronary heart disease in hyperphytosterolemic probands and their first-degree relatives. Metabolism. 1991;40:842–848. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(91)90013-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugano M, Morioka H, Ikeda I. A comparison of hypocholesterolemic activity of β-sitosterol and β-sitostanol in rats. J Nutr. 1977;107:2011–2019. doi: 10.1093/jn/107.11.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinemann T, Pietruck B, Kullak-Ublick G, Von Bergmann K. Comparison of sitosterol and sitostanol on inhibition of intestinal cholesterol absorption. Agents Actions Suppl. 1988;26:117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Law MR, Wald NJ, Thompson SG. By how much and how quickly does reduction in serum cholesterol concentration lower risk of ischaemic heart disease? BMJ. 1994;308:367–373. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6925.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gould AL, Rossouw JE, Santanell NC, Heyse JF, Furberg CD. Cholesterol reduction yields clinical benefit. Impact of statin trials. Circulation. 1998;97:946–952. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colhoun H, Prescott-Clarke P, editors. Health Survey for England 1994. London: HMSO; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Law MR, Wald NJ. An ecological study of serum cholesterol and ischaemic heart disease between 1950 and 1990. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994;48:305–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chisholm A, Mann J, Sutherland W, Duncan A, Skeaff M, Frampton C. Effect on lipoprotein profile of replacing butter with margarine in a low fat diet: randomised crossover study with hypercholesterolaemic subjects. BMJ. 1996;312:931–934. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7036.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wood R, Kubena K, O'Brien B, Tseng S, Martin G. Effect of butter, mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acid-enriched butter, trans fatty acid margarine, and zero trans fatty acid margarine on serum lipids and lipoproteins in healthy men. J Lipid Res. 1993;34:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denke MA. Lack of efficacy of low-dose sitostanol therapy as an adjunct to a cholesterol-lowering diet in men with moderate hypercholesterolemia. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61:392–396. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.2.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hallikainen MA, Sarkkinen ES, Uusitupa MIJ. Effects of low-fat stanol ester enriched margarine on concentrations of serum carotenoids in subjects with elevated serum cholesterol concentrations. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53:966–969. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group. The effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1029–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404143301501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Omenn GS, Goodman GE, Thornquist MD, Balmes J, Cullen MR, Glass A, et al. Effects of a combination of beta carotene and vitamin A on lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1150–1155. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605023341802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hepburn PA, Horner SA, Smith M. Safety evaluation of phytosterol esters. Subchronic 90-day oral toxicity study on phytosterol esters—a novel functional food. Food Chem Toxicol. 1999;37:521–532. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(99)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacques PF, Selhub J, Bostom AG, Wilson PWF, Rosenberg IH. The effect of folic acid fortification on plasma folate and total homocysteine concentrations. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1449–1454. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905133401901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]