Editor—Austoker's editorial on gaining informed consent for screening is timely.1 The National Screening Committee has commissioned two pilot sites for screening for bowel cancer, and there has been hot debate about what information should be given to potential participants and how.

If we follow past practice we would give very general information aimed at encouraging an invited age group to attend. “Screening for bowel cancer is effective; thousands of lives can be saved; the test is painless and free and can be done in the privacy of your home; cancers can be picked up early when they are easy to treat.” We would measure success by the uptake, and we would reassure those outside the invited group that screening is not important for them. If there is a downside to screening it is a price worth paying for the lives saved; mentioning it could deter people from attending and thus deprive them of the chance of benefit. So why the hot debate?

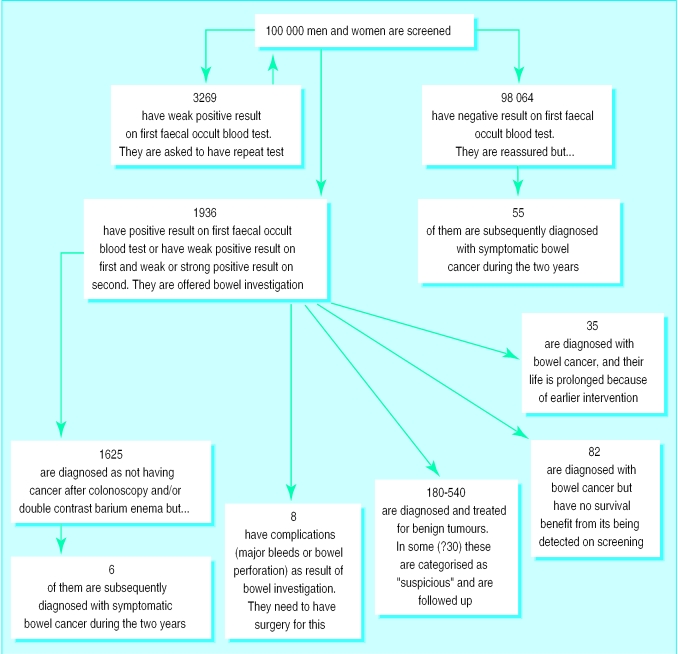

The screening committee held a workshop in 1998, where the consequences that an individual contemplating screening might need to be aware of were discussed.2 These were based on results of the Nottingham3 and Danish4 randomised controlled trials. Of the 178 cases of cancer among 100 000 people during a screening round, 35 have their life expectancy prolonged (representing the 15% reduction in mortality in the trials) (figure). Around 70 people have cancers that are not detected or have complications from investigation. Unless these 70 know in advance that these consequences are just as much a feature of screening as the lives saved then they will justifiably conclude that the screening programme is a shambles and may seek legal redress.

A relatively large group have adenomas detected by screening, most of whom if left unscreened would never develop a problem. Unless they know in advance that the discovery of benign and uncertain abnormalities is a feature of screening they are likely to credit the screening programme with having saved them from cancer. This boosts the popularity of screening but creates the myth that all dysplastic lesions are life threatening and must be found and eradicated. This can lead to the treatment of potential precancer (most of which would not cause a problem) becoming a bigger industry than the care of the sick.

The workshop was left with a dilemma. If you tell people all the consequences before they have a screening test then maybe it would deter them. If you do not tell them then you end up with expectations that are impossible to meet. Honesty is the best policy.

Figure.

Outcome during two-year screening round when 100 000 men and women aged 50-69 are screened for bowel cancer according to national pilot protocols

References

- 1.Austoker J. Gaining informed consent for screening. BMJ. 1999;319:722–723. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.722. . (18 September.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Screening Committee. Second colorectal cancer screening workshop. Information pack. Leeds: NHS Executive; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, Moss SM, Amar SS, Balfour TW. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348:1472–1477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jorgensen OD, Sondergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996;348:1467–1471. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]