Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic, much misinformation and disinformation emerged and spread rapidly via the internet, posing a severe public health challenge. While the need for eHealth literacy (eHL) has been emphasized, few studies have compared the difficulties involved in seeking and using COVID-19 information between adult internet users with low or high eHL.

Objective

This study examines the association between eHL and web-based health information–seeking behaviors among adult Japanese internet users. Moreover, this study qualitatively shed light on the difficulties encountered in seeking and using this information and examined its relationship with eHL.

Methods

This cross-sectional internet-based survey (October 2021) collected data from 6000 adult internet users who were equally divided into sample groups by gender, age, and income. We used the Japanese version of the eHL Scale (eHEALS). We also used a Digital Health Literacy Instrument (DHLI) adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic to assess eHL after we translated it to Japanese. Web-based health information–seeking behaviors were assessed by using a 10-item list of web sources and evaluating 10 topics participants searched for regarding COVID-19. Sociodemographic and other factors (eg, health-related behavior) were selected as covariates. Furthermore, we qualitatively explored the difficulties in information seeking and using. The descriptive contents of the responses regarding difficulties in seeking and using COVID-19 information were analyzed using an inductive qualitative content analysis approach.

Results

Participants with high eHEALS and DHLI scores on information searching, adding self-generated information, evaluating reliability, determining relevance, and operational skills were more likely to use all web sources of information about COVID-19 than those with low scores. However, there were negative associations between navigation skills and privacy protection scores when using several information sources, such as YouTube (Google LLC), to search for COVID-19 information. While half of the participants reported no difficulty seeking and using COVID-19 information, participants who reported any difficulties, including information discernment, incomprehensible information, information overload, and disinformation, had lower DHLI score. Participants expressed significant concerns regarding “information quality and credibility,” “abundance and shortage of relevant information,” “public trust and skepticism,” and “credibility of COVID-19–related information.” Additionally, they disclosed more specific concerns, including “privacy and security concerns,” “information retrieval challenges,” “anxieties and panic,” and “movement restriction.”

Conclusions

Although Japanese internet users with higher eHEALS and total DHLI scores were more actively using various web sources for COVID-19 information, those with high navigation skills and privacy protection used web-based information about COVID-19 cautiously compared with those with lower proficiency. The study also highlighted an increased need for information discernment when using social networking sites in the “Health 2.0” era. The identified categories and themes from the qualitative content analysis, such as “information quality and credibility,” suggest a framework for addressing the myriad challenges anticipated in future infodemics.

Keywords: COVID-19, infectious, public health, SARS-COV-2, respiratory, eHealth, health communication, web-based information, DHLI, eHEALS, internet, mixed methods study, adult population, Asia, Asian, cross sectional, survey, surveys, questionnaire, questionnaires, Japan, Japanese, information seeking, information behavior, information behavior, health literacy, eHealth literacy, digital health literacy

Introduction

Background

The internet is a powerful source of information on health behavior, health, and medical care. Most of the general adult population uses the internet in Japan, as in other high-income countries [1-3]. Approximately 73% of Japanese internet users have searched for health information in the past 12 months [4]. However, many websites providing health information are unreliable and may be more linked to promoting commercial goods or private health services [5-7]. Misinformation (ie, false information distributed without the intention to cause harm) and disinformation (ie, false information shared deliberately to cause harm) may negatively affect people’s physical and mental health, increase stigmatization, and threaten precious health gains, which lead to poor observance of public health measures [8,9]. Therefore, eHealth literacy (eHL), defined as the ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information on the internet to address or solve a health problem, is essential for accessing and using reliable health information via the internet.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, an “infodemic”—an epidemic of misinformation or disinformation—emerged and spread rapidly via the internet, posing a severe public health problem [10]. The COVID-19 infodemic has highlighted that poor eHL is a major challenge in using COVID-19 information on the internet [11]. People with poor health literacy are more likely to be confused by COVID-19 information on the internet [12]. Therefore, there is a need to improve health communication strategies for people with poor eHL to access reliable COVID-19 information on the internet easily.

Understanding the COVID-19 information–seeking behavior and identifying the difficulties internet users with low eHL are confronted with when dealing with this information are essential for improving communication strategies on COVID-19 and other health crises. The COVID-19 health literacy (COVID-HL) network surveyed digital health literacy (DHL), defined to have the same meaning as eHL [13]. Studies of the COVID-HL network revealed that university students with low eHL were more likely to use social media but less likely to use search engines and websites of official institutions than those with high eHL using quantitative data [14-18]. However, few studies have compared the difficulties individuals encounter when seeking and using COVID-19 information identified by qualitative content analysis between internet users with low and high eHL as estimated by an assessment tool. Mixed methods analyses, which integrate both quantitative and qualitative data, could increase our understanding of these difficulties and inform the development of strategies to enhance eHL for all individuals and improve the quality of web-based content. In addition, a limitation of these prior studies was that they included only college students [14-18] or physicians [19]. Examining the associations of eHL with health information–seeking behavior among other age groups is needed because the internet is used by not only younger adults but also different age groups, and older adults are reported to have barriers to seeking health information from the internet [1,2].

Objective

Comparing the subjective difficulties in seeking information between internet users with high and low eHL would help improve the strategies promoting access to reliable COVID-19 information. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the association between eHL and web-based health information–seeking behaviors using a mixed methods strategy. In addition, this study aimed to qualitatively shed light on the difficulties encountered in seeking and using this information, and to examine its relationship with eHL.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

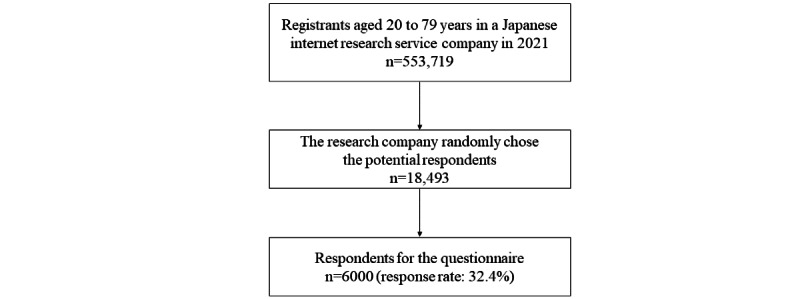

This study used data from a cross-sectional internet-based survey that was conducted in Japan in October 2021. The study participants were recruited from the registrants of a Japanese internet research company (MyVoice Communication, Inc), who were asked to respond to the survey. This research company has approximately 553,719 registrants who could respond to this survey and obtained detailed sociodemographic data from each participant upon registration in 2021.

Study Participants

This study aimed to collect data from 6000 men and women aged 20 to 79 years. The participants were equally divided into 132 sample groups categorized by gender (men and women), age (6 categories: 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, and 70-79 years), and income (11 categories: <1, 1-<2, 2-<3, 3-<4, 4-<5, 5-<6, 6-<7, 7-<8, 8-<9, 9-<10, ≥10 million Yen [1 Yen=US $0.0088]; October 2021), with 45 participants in each group. The internet research service company randomly chose 250 potential respondents to include 45 participants in each group from the registered participants in accordance with the company’s response rate data. Potential respondents could log into a protected site area using a unique ID and password. After the desired number of participants voluntarily signed a web-based informed consent form and completed a sociodemographic information form, further participants were no longer accepted.

Ethical Considerations

The Ethics Committees of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute for Geriatrics and Gerontology (R21-055) and Kyoto University (R3191) approved the study protocol. All procedures followed the Ethical Guidelines of the Medical and Biological Research Involving Human Subjects established by the Japanese government. Data for analysis was provided by the research company after deidentification. Finally, we obtained informed consent from participants before the survey. Reward points valued at 130 Yen were provided as incentives for participation.

Measures

Exposure: eHL

The Japanese version of the eHL Scale (J-eHEALS) was used to assess eHL for using health information on the internet as a 1-way communication channel (Health 1.0) among participants [20-22]. We selected eHL Scale (eHEALS) because it is the most widely used DHL scale in the world and is easy to answer for participants [23]. The J-eHEALS used a 5-point Likert scale to measure perceived eHL (from 1 [strongly disagree] to 5 [strongly agree]; score range=8-40). To validate the J-eHEALS, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using data from the survey [20]. We divided the J-eHEALS scores into 2 categories (high and low) relative to the median score.

Moreover, the Digital Health Literacy Instrument (DHLI) adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic was also used to evaluate eHL levels, including literacy for using social networking sites (SNSs)—such as Facebook (Meta Platforms, Inc) and Twitter (Twitter, Inc)—referred to as “Health 2.0” [15]. The DHLI was designed to assess eHL for Health 1.0 and Health 2.0 and is widely used throughout the world [14-18,22]. We used J-eHEALS and DHLI to evaluate eHL levels for both Health 1.0 and Health 2.0. The DHLI contains 7 subscales: information searching, adding self-generated content, evaluating reliability, determining relevance, operational skills, navigation skills, and protecting privacy. Each subscale included 3 items to be answered on a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 [very difficult] to 4 [very easy]). The COVID-HL network used DHLI adapted to COVID-19 and did not use the subscales of operational and navigation DHLI skills adapted to COVID-19 [13]. However, we included these subscales because they were crucial to accessing health information and navigating the internet. Moreover, although a recent study developed the DHLI [24], data on these skills adapted to COVID-19 among adult internet users in Japan were lacking. We divided each subscale and the total score of the DHLI into 1 of 2 categories (high or low) relative to the median score based on previous studies [14-18]. We translated DHLI adapted to the COVID-19 to Japanese, back translated it, and then confirmed their authors (Multimedia Appendix 1).

Outcomes: Web-Based Health Information–Seeking Behavior

The measures of web-based health information–seeking behaviors on the COVID-19 pandemic were assessed using a list of 10 different web sources: search engines (such as Google [Google LLC], Bing [Microsoft Corp], and Yahoo! [Yahoo Inc]), websites of public authorities (such as Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and the Japan Medical Association), Wikipedia, web-based encyclopedias, SNSs (such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter), YouTube, blogs providing medicine- and health-related information, medicine- and health-related question and answer sites (such as Yahoo! Answers), medicine- and health-related information portals, websites run by physicians or medical facilities, and news portal sites (including information gathered from newspapers and TV stations). These items were answered using a 5-point scale (0=do not know, 1=never, 2=often, 3=rarely, 4=sometimes, and 5=often). They were then assigned to either a “do not know–rarely” or “sometimes–often” category.

Moreover, we asked the participants to indicate from a list of 10 topics what they were searching for regarding COVID-19: the prevalence (such as number of people infected), infection route, symptoms, preventive measures (including disinfection and handwashing), rules and behavior (such as disinfection), assessment of its current status (such as declarations, measures, and stages), recommendations (including information from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and municipal governments), refraining from specific actions (such as eating out, traveling, and commuting to work), the economic and social effects, dealing with the psychological stress it causes, and information concerning the vaccine (effectiveness, side effects, and vaccination status). Participants answered “yes” or “no” to these items.

Sociodemographic and Other Variables

Sociodemographic and other variables were included as covariates in this regression model used by prior studies that examined the factors associated with eHL (gender, age groups, equivalent income, education status, marital status, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, physical exercise habits, and conditions that could likely lead to severe COVID-19 illness) [20-22]. Equivalent income was estimated by dividing annual income by the square root of the number of families [25]. We divided the equivalent income into 12 categories (<1-≥10 million Yen and “not answered”). Education status was divided into 4 categories (≤high school graduate, 2-year college or career college, higher university education, and “not answered”). Regarding marital status, the participants who answered “married” were categorized as “married.” The participants who answered “never married,” “widowed,” or “divorced” were categorized as “not married.” Concerning health behaviors, we assessed 3 items related to smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical exercise. Regarding smoking status, responses such as “never” or “quit” were categorized as “no smoking” and “smoking” or “sometimes smoking” as “smoking.” Alcohol consumption was determined using “yes” or “no” responses and the quantity of alcohol consumed. The participants who answered “no” or “quit” were categorized as “no.” Participants who responded with an alcohol intake of <20 g at once were categorized as “<20 g/once,” and those who drank alcohol ≥20 g at once were categorized as “≥20 g/once.” The physical exercise of participants was assessed subjectively based on whether they performed a 30-minute physical exercise ≥2 times a week for a year or longer (“yes” or “no”). We selected 6 conditions (hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, heart diseases, and chronic kidney diseases; BMI ≥30) to determine the possibility of becoming severely ill with COVID-19. “Yes” responses to ≥1 questions concerning the prevalence of conditions that were likely to cause severe illness with COVID-19 were categorized as “Yes.”

Difficulties in Seeking and Using COVID-19 Information

We asked the participants the descriptive open-ended question, “What difficulties did you have in seeking and using COVID-19-related information on the internet?” The item was in the required field and thus could not be left unanswered.

Analysis Using a Mixed Methods Strategy

Overview

We used the concurrent triangulation design of mixed methods strategy to analyze both quantitative and qualitative data in the internet-based survey [26]. In mixed methods analyses, the use of complementary methods integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches to address a complex question can generate deeper insights than using either approach alone or both approaches separately [27]. Mixed methods research enables a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation by integrating both quantitative and qualitative data. Furthermore, findings can be validated across different data sets by using both quantitative and qualitative methods. The triangulation of data from multiple methods enhances the credibility and reliability of a study’s findings. By adopting a mixed methods approach, it is possible to attain a broader understanding of the association between eHL and web-based health information–seeking behaviors, as well as the difficulties encountered in seeking and using this information.

Qualitative Content Analysis of Qualitative Data

Descriptive responses regarding difficulties in seeking and using COVID-19 information were analyzed using the inductive qualitative content analysis approach [28-30]. The contents were inductively organized into codes and categories to achieve trustworthiness [29]. YT and SM performed the analysis. All the responses were read and interpreted repeatedly. After discussing the meanings of the responses, phrases or sentences were coded for the analysis. The coding frame was changed when new codes emerged, and sentences were reread using the new structure. This constant comparison process was also used to develop conceptualize the responses into broad categories after further discussion. We finally aggregated categories into themes. We used the MAXQDA Analytics Pro 2022 (version 22.4.1; VERBI Software GmbH) for qualitative content analysis.

Statistical Analysis of Quantitative Data

First, a chi-square test was performed to compare the proportion of participants with low and high eHL by assessing the eHEALS and subscales of the DHLI. The internal consistencies of the subscales and the total scale were assessed using Cronbach α. We then examined the association of eHL levels with using web sources of COVID-19 information by using a multivariable logistic regression model that adjusted for all covariates. In addition, the associations of eHL levels with searching for specific COVID-19 topics were examined using a multivariable logistic regression model that adjusted for all covariates. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% CIs were estimated. We explored the relationship between eHL and categories of difficulties more thoroughly. eHEALS and DHLI total scores were classified into quartiles to observe variations in dose response, followed by the performance of the Cochrane-Armitage test for trend analysis. Two-tailed P values <.05 were considered significant. All analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 28.0; IBM Corp).

Results

Study Participant Selection

Figure 1 illustrates this study’s participant selection process. The research company chose 18,493 potential respondents in October 2021, and 6000 responses were obtained from respondents who provided complete information for the study variables (response rate: 32.4%).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient selection in this study.

Characteristics of Study Participants

The proportions of each gender and age group were identical (Table 1). The proportion of participants whose equivalent income was 3 to 4 million Yen was 19.98% (1199/6000). About 48.45% (2907/6000) of the participants had graduated from university or had higher education, and 54.67% (3280/6000) were married. Approximately 16.13% (968/6000) of the participants reported a cigarette smoking habit, 61.45% (3687/6000) consumed alcohol, and 32.78% (1967/6000) exercised regularly. Moreover, 23.02% (1381/6000) of the respondents had ≥1 health conditions likely to lead to severe COVID-19 illness.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants.

| Characteristics | Participants (N=6000), n (%) | |

| Gender | ||

|

|

Men | 3000 (50) |

|

|

Women | 3000 (50) |

| Age groups (y) | ||

|

|

20-29 | 1000 (16.67) |

|

|

30-39 | 1000 (16.67) |

|

|

40-49 | 1000 (16.67) |

|

|

50-59 | 1000 (16.67) |

|

|

60-69 | 1000 (16.67) |

|

|

≥70 | 1000 (16.67) |

| Equivalent income (million Y en ; Y en 1=US $ 0.0088) | ||

|

|

<1 | 413 (6.88) |

|

|

1-<2 | 878 (14.63) |

|

|

2-<3 | 972 (16.2) |

|

|

3-<4 | 1199 (19.98) |

|

|

4-<5 | 852 (14.2) |

|

|

5-<6 | 486 (8.1) |

|

|

6-<7 | 430 (7.17) |

|

|

7-<8 | 165 (2.75) |

|

|

8-<9 | 70 (1.17) |

|

|

9-<10 | 72 (1.2) |

|

|

≥10 | 107 (1.78) |

|

|

Not answered | 356 (5.93) |

| Education status | ||

|

|

≤High school | 1768 (29.47) |

|

|

2-year college or career college | 1298 (21.63) |

|

|

University or higher education | 2907 (48.45) |

|

|

No answer | 27 (0.45) |

| Marital status | ||

|

|

No | 2683 (44.72) |

|

|

Yes | 3280 (54.67) |

|

|

Not answered | 37 (0.62) |

| Cigarette smoking | ||

|

|

No | 5032 (83.87) |

|

|

Yes | 968 (16.13) |

| Alcohol consumption | ||

|

|

No | 2313 (38.55) |

|

|

<20 g/once | 2053 (34.22) |

|

|

≥20 g/once | 1634 (27.23) |

| Physical exercise habit | ||

|

|

No | 4033 (67.22) |

|

|

Yes | 1967 (32.78) |

| Conditions that could likely lead to severe COVID-19 illness | ||

|

|

No | 4619 (76.98) |

|

|

Yes | 1381 (23.02) |

Scores and Internal Consistencies of the DHLI Among This Study’s Participants

Table 2 presents the DHLI scores and internal consistencies among the study participants. The 7 subscales’ internal consistencies (Cronbach α) ranged from acceptable to good (0.83-0.94). Moreover, the mean DHLI total score was 3.08 (SD 0.49), and Cronbach α of the complete scale was 0.92.

Table 2.

Scores and internal consistencies of the DHLIa,b.

| Subscales and total score of the DHLI | Values, mean (SD) | Values, median (IQR) | Cronbach α |

| Information search | 3.01 (0.61) | 3.0 (2.7-3.3) | 0.91 |

| Adding self-generated information | 2.73 (0.73) | 3.0 (2.0-3.0) | 0.94 |

| Evaluating reliability | 2.66 (0.65) | 2.7 (2.0-3.0) | 0.88 |

| Determining relevance | 2.87 (0.59) | 3.0 (2.7-3.0) | 0.90 |

| Operational skills | 3.31 (0.62) | 3.0 (3.0-4.0) | 0.88 |

| Navigation skills | 3.59 (0.73) | 4.0 (3.3-4.0) | 0.83 |

| Privacy protection | 3.42 (0.91) | 4.0 (3.0-4.0) | 0.87 |

| Total score | 3.08 (0.49) | 3.1 (2.8-3.4) | 0.92 |

aDHLI: Digital Health Literacy Instrument.

bThe subscale scores and total DHLI score range from 0 to 4.

Differences of Characteristics by eHL From eHEALS and DHLI Subscales

Compared to those with low eHEALS, participants with high eHEALS were more likely to be older (P<.001), have higher income (P<.001) and education levels (P<.001), and be married (P=.007; Tables 3 and 4). Moreover, they were more likely to consume alcohol (P=.02) and have physical exercise habits (P<.001) and conditions leading to severe COVID-19 illness (P=.004) than those with low eHEALS.

Table 3.

Differences of characteristics based on the scores of eHEALSa, DHLIb, and its subscales.

| Characteristic | eHEALS | Information searching | Adding self-generated information | Evaluation reliability | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2228), n (%) | High (n=3772), n (%) | P valuec | Low (n=1613), n (%) | High (n=4387), n (%) | P valuec | Low (n=2702), n (%) | High (n=3298), n (%) | P valuec | Low (n=2475), n (%) | High (n=3525), n (%) | P valuec | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gender | .24 |

|

.47 |

|

.04 |

|

<.001 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Men | 1136 (50.99) | 1864 (49.42) |

|

794 (49.23) | 2206 (50.28) |

|

1311 (48.52) | 1689 (51.21) |

|

1135 (45.86) | 1865 (52.91) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Women | 1092 (49.01) | 1908 (50.58) |

|

819 (50.77) | 2181 (49.72) |

|

1391 (51.48) | 1609 (48.79) |

|

1340 (54.14) | 1660 (47.09) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Age groups (y) | <.001 |

|

.83 |

|

.17 |

|

<.001 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

20-29 | 421 (18.9) | 579 (15.35) |

|

272 (16.86) | 728 (16.59) |

|

420 (15.54) | 580 (17.59) |

|

362 (14.63) | 638 (18.1) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

30-39 | 376 (16.88) | 624 (16.54) |

|

268 (16.62) | 732 (16.69) |

|

453 (16.77) | 547 (16.59) |

|

389 (15.72) | 611 (17.33) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

40-49 | 374 (16.79) | 626 (16.6) |

|

271 (16.8) | 729 (16.62) |

|

480 (17.76) | 520 (15.77) |

|

405 (16.36) | 595 (16.88) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

50-59 | 387 (17.37) | 613 (16.25) |

|

256 (15.87) | 744 (16.96) |

|

442 (16.36) | 558 (16.92) |

|

424 (17.13) | 576 (16.34) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

60-69 | 355 (15.93) | 645 (17.1) |

|

263 (16.31) | 737 (16.8) |

|

456 (16.88) | 544 (16.49) |

|

422 (17.05) | 578 (16.4) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

≥70 | 315 (14.14) | 685 (18.16) |

|

283 (17.54) | 717 (16.34) |

|

451 (16.69) | 549 (16.65) |

|

473 (19.11) | 527 (14.95) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Equivalent income (million Yen; Y en 1=US $ 0.0088) | <.001 |

|

<.001 |

|

<.001 |

|

<.001 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

<1 | 177 (7.94) | 236 (6.26) |

|

131 (8.12) | 282 (6.43) |

|

202 (7.48) | 211 (6.4) |

|

182 (7.35) | 231 (6.55) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

1-<2 | 375 (16.83) | 503 (13.34) |

|

279 (17.3) | 599 (13.65) |

|

468 (17.32) | 410 (12.43) |

|

433 (17.49) | 445 (12.62) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

2-<3 | 394 (17.68) | 578 (15.32) |

|

270 (16.74) | 702 (16) |

|

468 (17.32) | 504 (15.28) |

|

439 (17.74) | 533 (15.12) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

3-<4 | 437 (19.61) | 762 (20.2) |

|

320 (19.84) | 879 (20.04) |

|

537 (19.87) | 662 (20.07) |

|

491 (19.84) | 708 (20.09) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

4-<5 | 300 (13.46) | 552 (14.63) |

|

208 (12.9) | 644 (14.68) |

|

366 (13.55) | 486 (14.74) |

|

336 (13.58) | 516 (14.64) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

5-<6 | 166 (7.45) | 320 (8.48) |

|

110 (6.82) | 376 (8.57) |

|

189 (6.99) | 297 (9.01) |

|

177 (7.15) | 309 (8.77) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

6-<7 | 130 (5.83) | 300 (7.95) |

|

93 (5.77) | 337 (7.68) |

|

141 (5.22) | 289 (8.76) |

|

145 (5.86) | 285 (8.09) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

7-<8 | 45 (2.02) | 120 (3.18) |

|

33 (2.05) | 132 (3.01) |

|

58 (2.15) | 107 (3.24) |

|

48 (1.94) | 117 (3.32) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

8-<9 | 24 (1.08) | 46 (1.22) |

|

15 (0.93) | 55 (1.25) |

|

28 (1.04) | 42 (1.27) |

|

18 (0.73) | 52 (1.48) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

9-<10 | 24 (1.08) | 48 (1.27) |

|

14 (0.87) | 58 (1.32) |

|

16 (0.59) | 56 (1.7) |

|

14 (0.57) | 58 (1.65) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

≥10 | 17 (0.76) | 90 (2.39) |

|

12 (0.74) | 95 (2.17) |

|

27 (1) | 80 (2.43) |

|

18 (0.73) | 89 (2.52) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Not answered | 139 (6.24) | 217 (5.75) |

|

128 (7.94) | 228 (5.2) |

|

202 (7.48) | 154 (4.67) |

|

174 (7.03) | 182 (5.16) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Education status | <.001 |

|

.001 |

|

<.001 |

|

<.001 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

≤High school | 725 (32.54) | 1043 (27.65) |

|

528 (32.73) | 1240 (28.27) |

|

879 (32.53) | 889 (26.96) |

|

852 (34.42) | 916 (25.99) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

2-year college or career college | 443 (19.88) | 855 (22.67) |

|

321 (19.9) | 977 (22.27) |

|

590 (21.84) | 708 (21.47) |

|

521 (21.05) | 777 (22.04) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

≥University | 1053 (47.26) | 1854 (49.15) |

|

752 (46.62) | 2155 (49.12) |

|

1216 (45) | 1691 (51.27) |

|

1087 (43.92) | 1820 (51.63) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Not answered | 7 (0.31) | 20 (0.53) |

|

12 (0.74) | 15 (0.34) |

|

17 (0.63) | 10 (0.3) |

|

15 (0.61) | 12 (0.34) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Marital status | .007 |

|

.002 |

|

.03 |

|

.14 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

No | 1049 (47.08) | 1634 (43.32) |

|

774 (47.99) | 1909 (43.51) |

|

1253 (46.37) | 1430 (43.36) |

|

1094 (44.2) | 1589 (45.08) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Yes | 1170 (52.51) | 2110 (55.94) |

|

825 (51.15) | 2455 (55.96) |

|

1429 (52.89) | 1851 (56.12) |

|

1360 (54.95) | 1920 (54.47) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Not answered | 9 (0.4) | 28 (0.74) |

|

14 (0.87) | 23 (0.52) |

|

20 (0.74) | 17 (0.52) |

|

21 (0.85) | 16 (0.45) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Cigarette smoking | .63 |

|

.13 |

|

<.001 |

|

<.001 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

No | 1862 (83.57) | 3170 (84.04) |

|

1372 (85.06) | 3660 (83.43) |

|

2329 (86.2) | 2703 (81.96) |

|

2129 (86.02) | 2903 (82.35) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Yes | 366 (16.43) | 602 (15.96) |

|

241 (14.94) | 727 (16.57) |

|

373 (13.8) | 595 (18.04) |

|

346 (13.98) | 622 (17.65) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol consumption | .02 |

|

<.001 |

|

<.001 |

|

<.001 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

No | 911 (40.89) | 1402 (37.17) |

|

680 (42.16) | 1633 (37.22) |

|

1117 (41.34) | 1196 (36.26) |

|

1031 (41.66) | 1282 (36.37) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

<20 g/once | 731 (32.81) | 1322 (35.05) |

|

555 (34.41) | 1498 (34.15) |

|

935 (34.6) | 1118 (33.9) |

|

856 (34.59) | 1197 (33.96) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

≥20 g/once | 586 (26.3) | 1048 (27.78) |

|

378 (23.43) | 1256 (28.63) |

|

650 (24.06) | 984 (29.84) |

|

588 (23.76) | 1046 (29.67) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical exercise habit | <.001 |

|

<.001 |

|

<.001 |

|

<.001 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

No | 1683 (75.54) | 2350 (62.3) |

|

1157 (71.73) | 2876 (65.56) |

|

1957 (72.43) | 2076 (62.95) |

|

1781 (71.96) | 2252 (63.89) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Yes | 545 (24.46) | 1422 (37.7) |

|

456 (28.27) | 1511 (34.44) |

|

745 (27.57) | 1222 (37.05) |

|

694 (28.04) | 1273 (36.11) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Conditions leading to severe COVID-19 illness | .004 |

|

.004 |

|

.24 |

|

.16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

No | 1745 (78.32) | 2874 (76.19) |

|

1200 (74.4) | 3419 (77.93) |

|

2061 (76.28) | 2558 (77.56) |

|

1883 (76.08) | 2736 (77.62) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Yes | 483 (21.68) | 898 (23.81) |

|

413 (25.6) | 968 (22.07) |

|

641 (23.72) | 740 (22.44) |

|

592 (23.92) | 789 (22.38) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

aeHEALS: eHealth Literacy Scale.

bDHLI: Digital Health Literacy Instrument.

cThe chi-square test.

Table 4.

Differences of characteristics based on the scores of eHEALSa, DHLIb, and its subscales (continued).

| Characteristic | Determining relevance | Operational skills | Navigation skills | Privacy protection | Total score | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2051), n (%) | High (n=3949), n (%) | P valuec | Low (n=1076), n (%) | High (n=4924), n (%) | P valuec | Low (n=1905), n (%) | High (n=4095), n (%) | P valuec | Low (n=2206), n (%) | High (n=3794), n (%) | P valuec | Low (n=3264), n (%) | High (n=2736), n (%) | P valuec | ||||||||||||||

| Gender | .17 |

|

<.001 |

|

.002 |

|

.75 |

|

.002 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Men | 1051 (51.24) | 1949 (49.35) |

|

455 (42.29) | 2545 (51.69) |

|

896 (47.03) | 2104 (51.38) |

|

1109 (50.27) | 1891 (49.84) |

|

1572 (48.16) | 1428 (52.19) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Women | 1000 (48.76) | 2000 (50.65) |

|

621 (57.71) | 2379 (48.31) |

|

1009 (52.97) | 1991 (48.62) |

|

1097 (49.73) | 1903 (50.16) |

|

1692 (51.84) | 1308 (47.81) |

|

|||||||||||||

| Age groups (y) | .73 |

|

<.001 |

|

<.001 |

|

<.001 |

|

<.001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

20-29 | 339 (16.53) | 661 (16.74) |

|

159 (14.78) | 841 (17.08) |

|

313 (16.43) | 687 (16.78) |

|

378 (17.14) | 622 (16.39) |

|

500 (15.32) | 500 (18.27) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

30-39 | 334 (16.28) | 666 (16.87) |

|

163 (15.15) | 837 (17) |

|

307 (16.12) | 693 (16.92) |

|

349 (15.82) | 651 (17.16) |

|

514 (15.75) | 486 (17.76) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

40-49 | 359 (17.5) | 641 (16.23) |

|

147 (13.66) | 853 (17.32) |

|

269 (14.12) | 731 (17.85) |

|

323 (14.64) | 677 (17.84) |

|

527 (16.15) | 473 (17.29) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

50-59 | 330 (16.09) | 670 (16.97) |

|

168 (15.61) | 832 (16.9) |

|

298 (15.64) | 702 (17.14) |

|

340 (15.41) | 660 (17.4) |

|

535 (16.39) | 465 (17) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

60-69 | 337 (16.43) | 663 (16.79) |

|

204 (18.96) | 796 (16.17) |

|

303 (15.91) | 697 (17.02) |

|

356 (16.14) | 644 (16.97) |

|

559 (17.13) | 441 (16.12) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

≥70 | 352 (17.16) | 648 (16.41) |

|

235 (21.84) | 765 (15.54) |

|

415 (21.78) | 585 (14.29) |

|

460 (20.85) | 540 (14.23) |

|

629 (19.27) | 371 (13.56) |

|

|||||||||||||

| Equivalent income (million Yen; Yen 1=US $0.0088) | <.001 |

|

<.001 |

|

.005 |

|

.01 |

|

<.001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

<1 | 159 (7.75) | 254 (6.43) |

|

98 (9.11) | 315 (6.4) |

|

149 (7.82) | 264 (6.45) |

|

155 (7.03) | 258 (6.8) |

|

246 (7.54) | 167 (6.1) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

1-<2 | 340 (16.58) | 538 (13.62) |

|

208 (19.33) | 670 (13.61) |

|

296 (15.54) | 582 (14.21) |

|

339 (15.37) | 539 (14.21) |

|

542 (16.61) | 336 (12.28) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

2-<3 | 340 (16.58) | 632 (16) |

|

187 (17.38) | 785 (15.94) |

|

312 (16.38) | 660 (16.12) |

|

382 (17.32) | 590 (15.55) |

|

559 (17.13) | 413 (15.1) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

3-<4 | 418 (20.38) | 781 (19.78) |

|

201 (18.68) | 998 (20.27) |

|

393 (20.63) | 806 (19.68) |

|

470 (21.31) | 729 (19.21) |

|

660 (20.22) | 539 (19.7) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

4-<5 | 293 (14.29) | 559 (14.16) |

|

136 (12.64) | 716 (14.54) |

|

280 (14.7) | 572 (13.97) |

|

316 (14.32) | 536 (14.13) |

|

458 (14.03) | 394 (14.4) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

5-<6 | 137 (6.68) | 349 (8.84) |

|

70 (6.51) | 416 (8.45) |

|

141 (7.4) | 345 (8.42) |

|

154 (6.98) | 332 (8.75) |

|

224 (6.86) | 262 (9.58) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

6-<7 | 127 (6.19) | 303 (7.67) |

|

47 (4.37) | 383 (7.78) |

|

117 (6.14) | 313 (7.64) |

|

141 (6.39) | 289 (7.62) |

|

198 (6.07) | 232 (8.48) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

7-<8 | 42 (2.05) | 123 (3.11) |

|

16 (1.49) | 149 (3.03) |

|

39 (2.05) | 126 (3.08) |

|

50 (2.27) | 115 (3.03) |

|

65 (1.99) | 100 (3.65) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

8-<9 | 18 (0.88) | 52 (1.32) |

|

8 (0.74) | 62 (1.26) |

|

22 (1.15) | 48 (1.17) |

|

26 (1.18) | 44 (1.16) |

|

35 (1.07) | 35 (1.28) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

9-<10 | 8 (0.39) | 64 (1.62) |

|

4 (0.37) | 68 (1.38) |

|

15 (0.79) | 57 (1.39) |

|

21 (0.95) | 51 (1.34) |

|

25 (0.77) | 47 (1.72) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

≥10 | 20 (0.98) | 87 (2.2) |

|

9 (0.84) | 98 (1.99) |

|

23 (1.21) | 84 (2.05) |

|

38 (1.72) | 69 (1.82) |

|

30 (0.92) | 77 (2.81) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Not answered | 149 (7.26) | 207 (5.24) |

|

92 (8.55) | 264 (5.36) |

|

118 (6.19) | 238 (5.81) |

|

114 (5.17) | 242 (6.38) |

|

222 (6.8) | 134 (4.9) |

|

|||||||||||||

| Education status | .007 |

|

<.001 |

|

.002 |

|

.06 |

|

<.001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

≤High school | 655 (31.94) | 1113 (28.18) |

|

451 (41.91) | 1317 (26.75) |

|

619 (32.49) | 1149 (28.06) |

|

618 (28.01) | 1150 (30.31) |

|

1053 (32.26) | 715 (26.13) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

2-year college or career college | 422 (20.58) | 876 (22.18) |

|

248 (23.05) | 1050 (21.32) |

|

410 (21.52) | 888 (21.68) |

|

460 (20.85) | 838 (22.09) |

|

707 (21.66) | 591 (21.6) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

≥University | 961 (46.86) | 1946 (49.28) |

|

364 (33.83) | 2543 (51.65) |

|

871 (45.72) | 2036 (49.72) |

|

1116 (50.59) | 1791 (47.21) |

|

1487 (45.56) | 1420 (51.9) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Not answered | 13 (0.63) | 14 (0.35) |

|

13 (1.21) | 14 (0.28) |

|

5 (0.26) | 22 (0.54) |

|

12 (0.54) | 15 (0.4) |

|

17 (0.52) | 10 (0.37) |

|

|||||||||||||

| Marital status | .04 |

|

<.001 |

|

.99 |

|

.58 |

|

.44 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

No | 913 (44.51) | 1770 (44.82) |

|

454 (42.19) | 2229 (45.27) |

|

850 (44.62) | 1833 (44.76) |

|

967 (43.83) | 1716 (45.23) |

|

1460 (44.73) | 1223 (44.7) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Yes | 1118 (54.51) | 2162 (54.75) |

|

600 (55.76) | 2680 (54.43) |

|

1043 (54.75) | 2237 (54.63) |

|

1225 (55.53) | 2055 (54.16) |

|

1780 (54.53) | 1500 (54.82) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Not answered | 20 (0.98) | 17 (0.43) |

|

22 (2.04) | 15 (0.3) |

|

12 (0.63) | 25 (0.61) |

|

14 (0.63) | 23 (0.61) |

|

24 (0.74) | 13 (0.48) |

|

|||||||||||||

| Cigarette smoking | .61 |

|

.18 |

|

.06 |

|

.56 |

|

.15 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

No | 1727 (84.2) | 3305 (83.69) |

|

917 (85.22) | 4115 (83.57) |

|

1573 (82.57) | 3459 (84.47) |

|

1842 (83.5) | 3190 (84.08) |

|

2758 (84.5) | 2274 (83.11) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Yes | 324 (15.8) | 644 (16.31) |

|

159 (14.78) | 809 (16.43) |

|

332 (17.43) | 636 (15.53) |

|

364 (16.5) | 604 (15.92) |

|

506 (15.5) | 462 (16.89) |

|

|||||||||||||

| Alcohol consumption | .008 |

|

<.001 |

|

.05 |

|

.02 |

|

.008 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

No | 844 (41.15) | 1469 (37.2) |

|

507 (47.12) | 1806 (36.68) |

|

721 (37.85) | 1592 (38.88) |

|

801 (36.31) | 1512 (39.85) |

|

1303 (39.92) | 1010 (36.92) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

<20 g/once | 685 (33.4) | 1368 (34.64) |

|

321 (29.83) | 1732 (35.17) |

|

627 (32.91) | 1426 (34.82) |

|

785 (35.58) | 1268 (33.42) |

|

1122 (34.38) | 931 (34.03) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

≥20 g/once | 522 (25.45) | 1112 (28.16) |

|

248 (23.05) | 1386 (28.15) |

|

557 (29.24) | 1077 (26.3) |

|

620 (28.11) | 1014 (26.73) |

|

839 (25.7) | 795 (29.06) |

|

|||||||||||||

| Physical exercise habit | <.001 |

|

.02 |

|

.01 |

|

<.001 |

|

<.001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

No | 1494 (72.84) | 2539 (64.29) |

|

755 (70.17) | 3278 (66.57) |

|

1238 (64.99) | 2795 (68.25) |

|

1413 (64.05) | 2620 (69.06) |

|

2276 (69.73) | 1757 (64.22) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Yes | 557 (27.16) | 1410 (35.71) |

|

321 (29.83) | 1646 (33.43) |

|

667 (35.01) | 1300 (31.75) |

|

793 (35.95) | 1174 (30.94) |

|

988 (30.27) | 979 (35.78) |

|

|||||||||||||

| Conditions that could lead to severe COVID-19 illness | .02 |

|

.01 |

|

<.001 |

|

<.001 |

|

<.001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

No | 1544 (75.28) | 3075 (77.87) |

|

797 (74.07) | 3822 (77.62) |

|

1397 (73.33) | 3222 (78.68) |

|

1603 (72.67) | 3016 (79.49) |

|

2424 (74.26) | 2195 (80.23) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Yes | 507 (24.72) | 874 (22.13) |

|

279 (25.93) | 1102 (22.38) |

|

508 (26.67) | 873 (21.32) |

|

603 (27.33) | 778 (20.51) |

|

840 (25.74) | 541 (19.77) |

|

|||||||||||||

aeHEALS: eHealth Literacy Scale.

bDHLI: Digital Health Literacy Instrument.

cThe chi-square test.

Among the participants with high total DHLI scores, there were higher proportions of men (P=.002), those aged 20 to 39 years (P<.001), those with higher equivalent income (P<.001), and those with higher education status (P<.001). They were more likely to consume alcohol (P=.02) and have physical exercise habits (P<.001) and less likely to have conditions that could lead to severe COVID-19 illness (P<.001). In addition, participants with higher subscores of DHLI generally consisted of higher proportions of men, had higher equivalent income and higher education status, and were more likely to be married. They were more likely to consume alcohol and less likely to have conditions that could lead to severe COVID-19 illness. Moreover, participants with higher scores on information searching, adding self-generated content, evaluating reliability, determining relevance, and operational skills were more likely to have an exercise habit. However, participants with higher scores on navigation skills and privacy protection were less likely to have an exercise habit.

Associations of eHL With Using Web Sources for Finding COVID-19 Information

Table 5 illustrates the proportion of “sometimes” or “often” responses to questions on using each web source. The most common web sources were search engines (4614/6000, 76.9%), followed by news portal sites (3350/6000, 55.83%). Participants with high eHEALS were more likely to use all web sources of information about COVID-19 than those with low eHEALS (Tables 6 and 7). The participants with high scores on the DHLI subscales information searching, adding self-generated information, evaluating reliability, determining relevance, and operational skills were also more likely to search for COVID-19 information using all web sources than participants with low scores on these subscales. Participants with high navigation skill scores were more likely to use search engines but less likely to use YouTube to search for COVID-19 information (AOR 0.88, 95% CI 0.79-0.99). Moreover, participants with high privacy protection scores were less likely to use websites of public authorities (AOR 0.80, 95% CI 0.72-0.89), Wikipedia (AOR 0.82, 95% CI 0.74-0.92), SNSs (AOR 0.74, 95% CI 0.66-0.83), YouTube (AOR 0.84, 95% CI 0.75-0.94), blogs providing medicine- and health-related information (AOR 0.81, 95% CI 0.72-0.92), question and answer sites (AOR 0.75, 95% CI 0.67-0.85), medicine- and health-related information portals (AOR 0.75, 95% CI 0.67-0.85), and websites run by physicians or medical facilities (AOR 0.72, 95% CI 0.64-0.81) for finding COVID-19 information. In addition, participants with high total DHLI scores were more likely to use all web sources of COVID-19 information than those with low total scores.

Table 5.

The proportion of “sometimes” or “often” responses to questions on using each web source.

| Web source | Participants (N=6000), n (%) |

| Search engines | 4614 (76.9) |

| News portal sites | 3350 (55.83) |

| Websites of public authorities | 2652 (44.2) |

| Wikipedia, web-based encyclopedias | 2232 (37.2) |

| Social media sites | 2088 (34.8) |

| YouTube | 2080 (34.67) |

| Websites run by physicians or medical facilities | 1718 (28.63) |

| Question and answer sites related to medicine and health | 1717 (28.62) |

| Medicine and health-related information portals | 1623 (27.05) |

| Blogs providing medicine and health-related information | 1379 (22.98) |

Table 6.

Associations of eHLa levels with using web sources for finding COVID-19 information.

| eHL | Search engines | Websites of public authorities | Wikipedia and web-based encyclopedias | SNSsb | YouTube | ||||||||||

|

|

Value, n (%) | AORc (95% CI)d | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)d | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)d | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)d | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)d | |||||

| eHEALSe | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2228) | 1583 (71.05) | 1.00 (reference) | 748 (33.57) | 1.00 (reference) | 641 (28.77) | 1.00 (reference) | 640 (28.73) | 1.00 (reference) | 638 (28.64) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=3772) | 3031 (80.36) | 1.57 (1.38-1.78) | 1904 (50.48) | 1.88 (1.68-2.11) | 1591 (42.18) | 1.70 (1.51-1.90) | 1448 (38.39) | 1.61 (1.43-1.81) | 1442 (38.23) | 1.50 (1.34-1.69) | ||||

| Information search | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=1613) | 1133 (70.24) | 1.00 (reference) | 591 (36.64) | 1.00 (reference) | 454 (28.15) | 1.00 (reference) | 466 (28.89) | 1.00 (reference) | 452 (28.02) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=4387) | 3481 (79.35) | 1.54 (1.35-1.76) | 2061 (46.98) | 1.44 (1.27-1.62) | 1778 (40.53) | 1.66 (1.46-1.89) | 1622 (36.97) | 1.41 (1.24-1.60) | 1628 (37.11) | 1.47 (1.30-1.67) | ||||

| Adding self-generated information | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2702) | 1992 (73.72) | 1.00 (reference) | 1034 (38.27) | 1.00 (reference) | 813 (30.09) | 1.00 (reference) | 786 (29.09) | 1.00 (reference) | 771 (28.53) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=3298) | 2622 (79.5) | 1.29 (1.14-1.46) | 1618 (49.06) | 1.42 (1.27-1.58) | 1419 (43.03) | 1.64 (1.47-1.84) | 1302 (39.48) | 1.51 (1.35-1.70) | 1309 (39.69) | 1.58 (1.41-1.76) | ||||

| Evaluating reliability | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2475) | 1849 (74.71) | 1.00 (reference) | 934 (37.74) | 1.00 (reference) | 747 (30.18) | 1.00 (reference) | 722 (29.17) | 1.00 (reference) | 718 (29.01) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=3525) | 2765 (78.44) | 1.16 (1.03-1.32) | 1718 (48.74) | 1.45 (1.30-1.61) | 1485 (42.13) | 1.56 (1.39-1.74) | 1366 (38.75) | 1.39 (1.24-1.56) | 1362 (38.64) | 1.44 (1.29-1.62) | ||||

| Determining relevance | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2051) | 1447 (70.55) | 1.00 (reference) | 760 (37.06) | 1.00 (reference) | 617 (30.08) | 1.00 (reference) | 603 (29.4) | 1.00 (reference) | 599 (29.21) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=3949) | 3167 (80.2) | 1.60 (1.41-1.82) | 1892 (47.91) | 1.46 (1.30-1.63) | 1615 (40.9) | 1.53 (1.37-1.72) | 1485 (37.6) | 1.39 (1.23-1.57) | 1481 (37.5) | 1.40 (1.25-1.58) | ||||

| Operational skills | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=1076) | 658 (61.15) | 1.00 (reference) | 310 (28.81) | 1.00 (reference) | 263 (24.44) | 1.00 (reference) | 260 (24.16) | 1.00 (reference) | 322 (29.93) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=4924) | 3956 (80.34) | 2.43 (2.09-2.82) | 2342 (47.56) | 2.07 (1.78-2.40) | 1969 (39.99) | 1.90 (1.62-2.21) | 1828 (37.12) | 1.67 (1.42-1.96) | 1758 (35.7) | 1.22 (1.05-1.41) | ||||

| Navigation skills | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=1905) | 1436 (75.38) | 1.00 (reference) | 845 (44.36) | 1.00 (reference) | 692 (36.33) | 1.00 (reference) | 643 (33.75) | 1.00 (reference) | 698 (36.64) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=4095) | 3178 (77.61) | 1.15 (1.01-1.31) | 1807 (44.13) | 1.00 (0.89-1.12) | 1540 (37.61) | 1.05 (0.94-1.18) | 1445 (35.29) | 1.06 (0.94-1.20) | 1382 (33.75) | 0.88 (0.79-0.99) | ||||

| Protecting privacy | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2206) | 1706 (77.33) | 1.00 (reference) | 1061 (48.1) | 1.00 (reference) | 891 (40.39) | 1.00 (reference) | 856 (38.8) | 1.00 (reference) | 826 (37.44) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=3794) | 2908 (76.65) | 1.01 (0.88-1.14) | 1591 (41.93) | 0.80 (0.72-0.89) | 1341 (35.35) | 0.82 (0.74-0.92) | 1232 (32.47) | 0.74 (0.66-0.83) | 1254 (33.05) | 0.84 (0.75-0.94) | ||||

| Total score of DHLIf | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=3264) | 2426 (74.33) | 1.00 (reference) | 1302 (39.89) | 1.00 (reference) | 1065 (32.63) | 1.00 (reference) | 997 (30.55) | 1.00 (reference) | 1040 (31.86) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=2736) | 2188 (79.97) | 1.34 (1.18-1.52) | 1350 (49.34) | 1.38 (1.24-1.54) | 1167 (42.65) | 1.46 (1.31-1.63) | 1091 (39.88) | 1.39 (1.24-1.56) | 1040 (38.01) | 1.25 (1.12-1.40) | ||||

aeHL: eHealth literacy.

bSNS: social networking site.

cAOR: adjusted odds ratio.

dMultivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted for all covariates (ie, gender, age groups, equivalent income, education status, marital status, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, physical exercise habit, and conditions leading to severe illness due to COVID-19).

eeHEALS: eHealth Literacy Scale.

fDHLI: Digital Health Literacy Instrument.

Table 7.

Associations of eHLa levels with using web sources for finding COVID-19 information (continued).

| eHL | Blogs providing medicine- and health-related information | Medicine- and health-related question and answer sites | Medicine- and health-related information portals | Websites run by physicians or medical facilities | News portal sites | ||||||

|

|

Value, n (%) | AORb (95% CI)c | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)c | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)c | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)c | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)c | |

| eHEALSd | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2228) | 292 (13.1) | 1.00 (reference) | 417 (18.72) | 1.00 (reference) | 336 (15.08) | 1.00 (reference) | 375 (16.83) | 1.00 (reference) | 1045 (46.9) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=3772) | 1087 (28.82) | 2.46 (2.13-2.84) | 1300 (34.46) | 2.08 (1.83-2.36) | 1287 (34.12) | 2.65 (2.31-3.04) | 1343 (35.6) | 2.51 (2.20-2.87) | 2305 (61.11) | 1.65 (1.48-1.85) |

| Information search | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=1613) | 232 (14.38) | 1.00 (reference) | 332 (20.58) | 1.00 (reference) | 305 (18.91) | 1.00 (reference) | 336 (20.83) | 1.00 (reference) | 789 (48.92) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=4387) | 1147 (26.15) | 2.00 (1.71-2.35) | 1385 (31.57) | 1.71 (1.49-1.97) | 1318 (30.04) | 1.73 (1.50-2.00) | 1382 (31.5) | 1.65 (1.44-1.90) | 2561 (58.38) | 1.40 (1.24-1.57) |

| Adding self-generated information | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2702) | 444 (16.43) | 1.00 (reference) | 610 (22.58) | 1.00 (reference) | 546 (20.21) | 1.00 (reference) | 591 (21.87) | 1.00 (reference) | 1419 (52.52) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=3298) | 935 (28.35) | 1.87 (1.64-2.13) | 1107 (33.57) | 1.64 (1.45-1.85) | 1077 (32.66) | 1.75 (1.55-1.98) | 1127 (34.17) | 1.71 (1.52-1.93) | 1931 (58.55) | 1.19 (1.07-1.33) |

| Evaluating reliability | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2475) | 378 (15.27) | 1.00 (reference) | 550 (22.22) | 1.00 (reference) | 481 (19.43) | 1.00 (reference) | 527 (21.29) | 1.00 (reference) | 1268 (51.23) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=3525) | 1001 (28.4) | 2.07 (1.81-2.37) | 1167 (33.11) | 1.70 (1.50-1.92) | 1142 (32.4) | 1.85 (1.63-2.10) | 1191 (33.79) | 1.75 (1.55-1.98) | 2082 (59.06) | 1.33 (1.20-1.49) |

| Determining relevance | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2051) | 336 (16.38) | 1.00 (reference) | 466 (22.72) | 1.00 (reference) | 407 (19.84) | 1.00 (reference) | 447 (21.79) | 1.00 (reference) | 1023 (49.88) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=3949) | 1043 (26.41) | 1.71 (1.49-1.97) | 1251 (31.68) | 1.48 (1.30-1.68) | 1216 (30.79) | 1.66 (1.46-1.90) | 1271 (32.19) | 1.58 (1.39-1.80) | 2327 (58.93) | 1.37 (1.23-1.53) |

| Operational skills | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=1076) | 162 (15.06) | 1.00 (reference) | 222 (20.63) | 1.00 (reference) | 186 (17.29) | 1.00 (reference) | 204 (18.96) | 1.00 (reference) | 439 (40.8) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=4924) | 1217 (24.72) | 1.78 (1.48-2.14) | 1495 (30.36) | 1.67 (1.41-1.97) | 1437 (29.18) | 1.86 (1.56-2.21) | 1514 (30.75) | 1.76 (1.49-2.09) | 2911 (59.12) | 2.01 (1.75-2.32) |

| Navigation skills | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=1905) | 430 (22.57) | 1.00 (reference) | 569 (29.87) | 1.00 (reference) | 530 (27.82) | 1.00 (reference) | 527 (27.66) | 1.00 (reference) | 1049 (55.07) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=4095) | 949 (23.17) | 1.06 (0.93-1.21) | 1148 (28.03) | 0.95 (0.84-1.07) | 1093 (26.69) | 0.96 (0.85-1.09) | 1191 (29.08) | 1.07 (0.95-1.21) | 2301 (56.19) | 1.06 (0.94-1.19) |

| Protecting privacy | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2206) | 569 (25.79) | 1.00 (reference) | 727 (32.96) | 1.00 (reference) | 687 (31.14) | 1.00 (reference) | 732 (33.18) | 1.00 (reference) | 1281 (58.07) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=3794) | 810 (21.35) | 0.81 (0.72-0.92) | 990 (26.09) | 0.75 (0.67-0.85) | 936 (24.67) | 0.75 (0.67-0.85) | 986 (25.99) | 0.72 (0.64-0.81) | 2069 (54.53) | 0.90 (0.81-1.01) |

| Total DHLIe score | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=3264) | 606 (18.57) | 1.00 (reference) | 830 (25.43) | 1.00 (reference) | 738 (22.61) | 1.00 (reference) | 799 (24.48) | 1.00 (reference) | 1691 (51.81) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=2736) | 773 (28.25) | 1.66 (1.47-1.89) | 887 (32.42) | 1.39 (1.24-1.57) | 885 (32.35) | 1.56 (1.39-1.76) | 919 (33.59) | 1.47 (1.31-1.65) | 1659 (60.64) | 1.43 (1.29-1.60) |

aeHL: eHealth literacy.

bAOR: adjusted odds ratio.

cMultivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted for all covariates (ie, gender, age groups, equivalent income, education status, marital status, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, physical exercise habit, and conditions leading to severe illness due to COVID-19).

deHEALS: eHealth Literacy Scale.

eDHLI: Digital Health Literacy Instrument.

Associations of eHL Levels With Searching Specific COVID-19 Topics

The most commonly searched specific COVID-19 topics were infectivity (4015/6000, 66.92%), followed by information about vaccine (3650/6000, 60.83%; Table 8). Participants with high eHEALS were more likely to search for all COVID-19-related topics than participants with low eHEALS (Tables 9 and 10). Moreover, participants with high total DHLI scores were more likely to search for information concerning infectivity and economic and social effects. In addition, participants with higher subscores of DHLI generally were more likely to search for information on the route of infection, assessment, economic and social effects, dealing with psychological stress, and the vaccine. However, the odds of searching for information on the route of infection and refraining from specific behaviors among participants with high navigation skills scores were 0.77 times (95% CI 0.67-0.89) and 0.88 times (95% CI 0.78-0.99) lower, respectively, than those among participants with lower scores. In addition, participants with high privacy protection scores were less likely to search for information on the route of infection (AOR 0.71, 95% CI 0.63-0.82), symptoms (AOR 0.81, 95% CI 0.73-0.90), preventive measures (AOR 0.74, 95% CI 0.66-0.83), rules and behaviors (AOR 0.87, 95% CI 0.77-0.99), assessment (AOR 0.84, 95% CI 0.75-0.96), refraining from specific behaviors (AOR 0.78, 95% CI 0.70-0.88), economic and social effects (AOR 0.83, 95% CI 0.72-0.94), and dealing with psychological stress (AOR 0.77, 95% CI 0.66-0.90).

Table 8.

The proportion of “yes” responses to questions on searching each topic about COVID-19.

| Topic about COVID-19 | Participants (N=6000), n (%) |

| The infectivity of the novel coronavirus | 4015 (66.92) |

| Information about the novel coronavirus vaccine | 3650 (60.83) |

| Symptoms of the novel coronavirus | 2494 (41.57) |

| Things individuals can do to prevent novel coronavirus infection | 1920 (32) |

| Refraining from certain behaviors | 1915 (31.92) |

| Rules and behavior regarding novel coronavirus infection prevention | 1530 (25.5) |

| Assessment of the current novel coronavirus infection status and recommendations | 1445 (24.08) |

| The economic and social effects of the novel coronavirus | 1260 (21) |

| Route of infection of the novel coronavirus | 1172 (19.53) |

| How to deal with the psychological stress caused by the novel coronavirus | 775 (12.92) |

Table 9.

Associations of eHLa levels with searching specific COVID-19 topics.

| eHL | The infectivity | Route of infection | Symptoms | Preventive measures | Rules and behaviors | ||||||

|

|

Value, n (%) | AORb (95% CI)c | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)c | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)c | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)c | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)c | |

| eHEALSd | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2228) | 1401 (62.88) | 1.00 (reference) | 319 (14.32) | 1.00 (reference) | 755 (33.89) | 1.00 (reference) | 553 (24.82) | 1.00 (reference) | 400 (17.95) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=3772) | 2614 (69.3) | 1.25 (1.11-1.40) | 853 (22.61) | 1.63 (1.41-1.89) | 1739 (46.1) | 1.58 (1.41-1.77) | 1367 (36.24) | 1.58 (1.40-1.79) | 1130 (29.96) | 1.78 (1.56-2.03) |

| Information search | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=1613) | 1010 (62.62) | 1.00 (reference) | 273 (16.92) | 1.00 (reference) | 646 (40.05) | 1.00 (reference) | 491 (30.44) | 1.00 (reference) | 388 (24.05) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=4387) | 3005 (68.5) | 1.25 (1.11-1.41) | 899 (20.49) | 1.21 (1.04-1.41) | 1848 (42.12) | 1.06 (0.94-1.19) | 1429 (32.57) | 1.07 (0.94-1.22) | 1142 (26.03) | 1.08 (0.94-1.24) |

| Adding self-generated information | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2702) | 1771 (65.54) | 1.00 (reference) | 453 (16.77) | 1.00 (reference) | 1124 (41.6) | 1.00 (reference) | 824 (30.5) | 1.00 (reference) | 653 (24.17) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=3298) | 2244 (68.04) | 1.05 (0.94-1.18) | 719 (21.8) | 1.29 (1.12-1.47) | 1370 (41.54) | 0.96 (0.86-1.07) | 1096 (33.23) | 1.09 (0.98-1.23) | 877 (26.59) | 1.09 (0.97-1.23) |

| Evaluating reliability | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2475) | 1655 (66.87) | 1.00 (reference) | 403 (16.28) | 1.00 (reference) | 1022 (41.29) | 1.00 (reference) | 772 (31.19) | 1.00 (reference) | 611 (24.69) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=3525) | 2360 (66.95) | 0.96 (0.86-1.08) | 769 (21.82) | 1.33 (1.16-1.53) | 1472 (41.76) | 1.02 (0.92-1.14) | 1148 (32.57) | 1.09 (0.97-1.22) | 919 (26.07) | 1.10 (0.97-1.24) |

| Determining relevance | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2051) | 1350 (65.82) | 1.00 (reference) | 344 (16.77) | 1.00 (reference) | 820 (39.98) | 1.00 (reference) | 594 (28.96) | 1.00 (reference) | 473 (23.06) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=3949) | 2665 (67.49) | 1.03 (0.92-1.16) | 828 (20.97) | 1.23 (1.07-1.42) | 1674 (42.39) | 1.05 (0.94-1.18) | 1326 (33.58) | 1.18 (1.05-1.34) | 1057 (26.77) | 1.16 (1.02-1.32) |

| Operational skills | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=1076) | 625 (58.09) | 1.00 (reference) | 187 (17.38) | 1.00 (reference) | 385 (35.78) | 1.00 (reference) | 284 (26.39) | 1.00 (reference) | 234 (21.75) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=4924) | 3390 (68.85) | 1.59 (1.38-1.83) | 985 (20) | 1.10 (0.92-1.31) | 2109 (42.83) | 1.37 (1.19-1.58) | 1636 (33.23) | 1.48 (1.27-1.73) | 1296 (26.32) | 1.39 (1.18-1.64) |

| Navigation skills | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=1905) | 1273 (66.82) | 1.00 (reference) | 433 (22.73) | 1.00 (reference) | 822 (43.15) | 1.00 (reference) | 639 (33.54) | 1.00 (reference) | 506 (26.56) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=4095) | 2742 (66.96) | 1.06 (0.94-1.19) | 739 (18.05) | 0.77 (0.67-0.89) | 1672 (40.83) | 0.96 (0.86-1.08) | 1281 (31.28) | 0.98 (0.86-1.10) | 1024 (25.01) | 1.01 (0.89-1.16) |

| Privacy protection | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2206) | 1490 (67.54) | 1.00 (reference) | 515 (23.35) | 1.00 (reference) | 1002 (45.42) | 1.00 (reference) | 816 (36.99) | 1.00 (reference) | 620 (28.11) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=3794) | 2525 (66.55) | 1.02 (0.91-1.15) | 657 (17.32) | 0.71 (0.63-0.82) | 1492 (39.33) | 0.81 (0.73-0.90) | 1104 (29.1) | 0.74 (0.66-0.83) | 910 (23.99) | 0.87 (0.77-0.99) |

| Total DHLI e score | |||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=3264) | 2142 (65.63) | 1.00 (reference) | 614 (18.81) | 1.00 (reference) | 1378 (42.22) | 1.00 (reference) | 1053 (32.26) | 1.00 (reference) | 833 (25.52) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

|

High (n=2736) | 1873 (68.46) | 1.14 (1.02-1.28) | 558 (20.39) | 1.06 (0.93-1.21) | 1116 (40.79) | 0.95 (0.86-1.06) | 867 (31.69) | 1.01 (0.90-1.13) | 697 (25.48) | 1.04 (0.92-1.18) |

aeHL: eHealth literacy.

bAOR: adjusted odds ratio.

cThe multivariable logistic regression model that adjusted for all covariates (ie, gender, age groups, equivalent income, education status, marital status, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, physical exercise habit, and conditions leading to severe illness due to COVID-19).

deHEALS: eHealth Literacy Scale.

eDHLI: Digital Health Literacy Instrument.

Table 10.

Associations of eHLa levels with searching the specific COVID-19 topics (continued).

| eHL | Assessment of the current novel coronavirus infection status | Refraining from specific behaviors | The economic and social effects of the novel coronavirus | Dealing with the psychological stress caused by the novel coronavirus | Information about the novel coronavirus vaccine | ||||||||||

|

|

Value, n (%) | AORb (95% CI)c | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)c | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)c | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)c | Value, n (%) | AOR (95% CI)c | |||||

| eHEALSd | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2228) | 371 (16.65) | 1.00 (reference) | 579 (25.99) | 1.00 (reference) | 322 (14.45) | 1.00 (reference) | 153 (6.87) | 1.00 (reference) | 1229 (55.16) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=3772) | 1074 (28.47) | 1.81 (1.58-2.07) | 1336 (35.42) | 1.43 (1.27-1.61) | 938 (24.87) | 1.83 (1.59-2.11) | 622 (16.49) | 2.47 (2.04-2.98) | 2421 (64.18) | 1.43 (1.28-1.60) | ||||

| Information search | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=1613) | 333 (20.64) | 1.00 (reference) | 498 (30.87) | 1.00 (reference) | 299 (18.54) | 1.00 (reference) | 167 (10.35) | 1.00 (reference) | 956 (59.27) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=4387) | 1112 (25.35) | 1.24 (1.08-1.43) | 1417 (32.3) | 1.02 (0.90-1.16) | 961 (21.91) | 1.19 (1.02-1.38) | 608 (13.86) | 1.35 (1.12-1.63) | 2694 (61.41) | 1.13 (1.01-1.28) | ||||

| Adding self-generated information | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2702) | 614 (22.72) | 1.00 (reference) | 859 (31.79) | 1.00 (reference) | 514 (19.02) | 1.00 (reference) | 306 (11.32) | 1.00 (reference) | 1692 (62.62) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=3298) | 831 (25.2) | 1.05 (0.92-1.19) | 1056 (32.02) | 0.94 (0.84-1.06) | 746 (22.62) | 1.18 (1.04-1.34) | 469 (14.22) | 1.23 (1.05-1.44) | 1958 (59.37) | 0.91 (0.81-1.01) | ||||

| Evaluating reliability | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2475) | 544 (21.98) | 1.00 (reference) | 789 (31.88) | 1.00 (reference) | 462 (18.67) | 1.00 (reference) | 290 (11.72) | 1.00 (reference) | 1536 (62.06) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=3525) | 901 (25.56) | 1.17 (1.03-1.32) | 1126 (31.94) | 0.99 (0.89-1.12) | 798 (22.64) | 1.24 (1.09-1.42) | 485 (13.76) | 1.17 (1.00-1.38) | 2114 (59.97) | 1.00 (0.90-1.12) | ||||

| Determining relevance | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2051) | 429 (20.92) | 1.00 (reference) | 615 (29.99) | 1.00 (reference) | 391 (19.06) | 1.00 (reference) | 230 (11.21) | 1.00 (reference) | 1222 (59.58) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=3949) | 1016 (25.73) | 1.22 (1.07-1.40) | 1300 (32.92) | 1.09 (0.97-1.23) | 869 (22.01) | 1.14 (1.00-1.31) | 545 (13.8) | 1.19 (1.01-1.41) | 2428 (61.48) | 1.10 (0.98-1.23) | ||||

| Operational skills | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=1076) | 177 (16.45) | 1.00 (reference) | 292 (27.14) | 1.00 (reference) | 164 (15.24) | 1.00 (reference) | 127 (11.8) | 1.00 (reference) | 582 (54.09) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=4924) | 1268 (25.75) | 1.73 (1.44-2.07) | 1623 (32.96) | 1.34 (1.15-1.57) | 1096 (22.26) | 1.57 (1.30-1.88) | 648 (13.16) | 1.15 (0.93-1.42) | 3068 (62.31) | 1.60 (1.39-1.84) | ||||

| Navigation skills | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=1905) | 454 (23.83) | 1.00 (reference) | 661 (34.7) | 1.00 (reference) | 421 (22.1) | 1.00 (reference) | 277 (14.54) | 1.00 (reference) | 1093 (57.38) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=4095) | 991 (24.2) | 1.07 (0.94-1.22) | 1254 (30.62) | 0.88 (0.78-0.99) | 839 (20.49) | 0.94 (0.82-1.08) | 498 (12.16) | 0.86 (0.73-1.01) | 2557 (62.44) | 1.30 (1.16-1.45) | ||||

| Privacy protection | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=2206) | 589 (26.7) | 1.00 (reference) | 799 (36.22) | 1.00 (reference) | 521 (23.62) | 1.00 (reference) | 334 (15.14) | 1.00 (reference) | 1305 (59.16) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=3794) | 856 (22.56) | 0.84 (0.75-0.96) | 1116 (29.41) | 0.78 (0.70-0.88) | 739 (19.48) | 0.83 (0.72-0.94) | 441 (11.62) | 0.77 (0.66-0.90) | 2345 (61.81) | 1.16 (1.04-1.29) | ||||

| Total DHLIe score | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Low (n=3264) | 751 (23.01) | 1.00 (reference) | 1054 (32.29) | 1.00 (reference) | 645 (19.76) | 1.00 (reference) | 404 (12.38) | 1.00 (reference) | 1980 (60.66) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

|

High (n=2736) | 694 (25.37) | 1.12 (0.99-1.27) | 861 (31.47) | 0.98 (0.87-1.09) | 615 (22.48) | 1.18 (1.03-1.34) | 371 (13.56) | 1.11 (0.95-1.29) | 1670 (61.04) | 1.10 (0.99-1.23) | ||||

aeHL: eHealth literacy.

bAOR: adjusted odds ratio.

cThe multivariable logistic regression model that adjusted for all covariates (gender, age groups, equivalent income, education status, marital status, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, physical exercise habit, and conditions leading to severe illness due to COVID-19).

deHEALS: eHealth Literacy Scale.

eDHLI: Digital Health Literacy Instrument.

Difficulties in Seeking and Using COVID-19 Information

Difficulties in seeking and using COVID-19 information were examined using a qualitative content analysis of 6000 valid answers to open-ended questions. Excluding 3151 (52.52%) participants who responded as perceiving no difficulties, we have listed the top 50 categories and themes (Table 11). “Information quality and credibility,” as theme I, included information discernment and disinformation. “Abundance and shortage of relevant information,” as theme II, included incomprehensible information and information overload. “Public trust and skepticism,” as theme III, included doubting (local) governments and doubting specialists and doctors. “Credibility of COVID-19–related information,” as theme IV, included vaccination information. These themes, including top 10 categories, cover common difficulties among people. “Privacy and security concerns,” as theme V, included protecting personal information. “Information retrieval challenges,” as theme VI, included time-consuming information search. “Anxieties and panic,” as theme VII, included anxiety and panic. “Movement restriction,” as theme VIII, included time-consuming information search. The number of categories in themes V to VIII was fewer than that in themes I to IV, indicating that the latter themes were related with relatively more specific difficulties.

Table 11.

Top 50 categories and themes of difficulties in seeking and using COVID-19 information.

| Categories | Themes | ||||||||

|

|

Ia | IIb | IIIc | IVd | Ve | VIf | VIIg | VIIIh | IXi |

| 1. Information discernment | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Incomprehensible information |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Information overload |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4. Vaccination information |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| 5. Disinformation | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6. Lack of information meeting their needs |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 7. Information without evidence | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 8. Information without credibility or trust | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 9. Lack of detailed patient information |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 10. Doubting (local) governments |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 11. Lack of information concerning their local area |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 12. Not seeking information |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| 13. Conflicting information | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 14. Lack of up-to-date information |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 15. Anxiety and panic |

|

|

|

|

|

` | ✓ |

|

|

| 16. Rabble-rousing information | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 17. Insufficient aggregated information of patients |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 18. Doubting specialists and doctors |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 19. Doubting the media |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 20. Lack of information after infection |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 21. Misinformation | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 22. Information control and manipulation | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 23. Information resources | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 24. Time-consuming information search |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

| 25. Lack of information on prospects |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 26. Technical terms and jargon |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 27. No answers to unknown virus |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| 28. Lack of information about other countries |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 29. Redundant or repetitive information |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 30. Information on infection risk and prevention |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| 31. Lack of information on COVID-19 testing |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| 32. Doubting the social media |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 33. Lack of information on the availability of essential services |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 34. Antivaccination and antigovernment | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 35. Lack of comprehensive information |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 36. Regulation and self-restraint |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

| 37. Operating PCs and smartphones |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

| 38. Protecting personal information |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

| 39. Lack of high-quality information |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 40. The early stage of COVID-19 |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| 41. Doubting various authorities that lack cooperation |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 42. How to deal with information | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 43. Information on advertisement |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 44. Information on SARS-CoV-2 |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| 45. Differentiating COVID-19 from a cold |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| 46. Lack of information suitable for oneself |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 47. Imbalance in information toward metropolitan areas |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 48. Lack of information for close contacts |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 49. Financial hardship |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| 50. Trust in authorities |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

aTheme I: information quality and credibility.

bTheme II: abundance and shortage of relevant information.

cTheme III: public trust and skepticism.