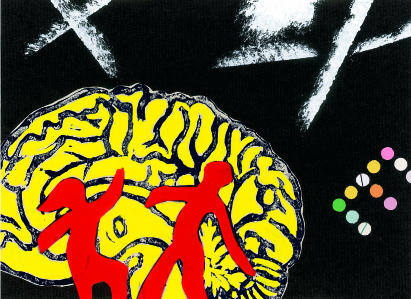

It has been recognised for some time that many disorders such as vascular malformations, hypertension, bacterial endocarditis, collagen vascular diseases, tumours, eclampsia, and blood dyscrasias can cause non-traumatic intracerebral haemorrhage in young adults. However, with the epidemic in the misuse of amphetamine, cocaine, and ecstasy—primarily among young people—traditional aetiological factors for haemorrhagic stroke are becoming overshadowed.

The association between amphetamine ingestion and intracerebral haemorrhage was first reported by Gericke in 1945, and it has become increasingly recognised in recent years.1–10 Previous reports, although noting the occurrence of intracerebral haemorrhage and subarachnoid haemorrhage, found no evidence of an underlying vascular abnormality on detailed microscopic examination of the cerebral vessels.2–9 The haemorrhages were explained by a necrotising angiitis related to amphetamine misuse associated with hypertension.7,9,11 In 1996, a necropsy study of 14 patients with intracerebral haemorrhages related to cocaine use found no evidence of an abnormal cerebral vasculature.12 Further investigation to seek an underlying cause was thought to be unnecessary.

There have, however, been two recent reports of ruptured arteriovenous malformations after amphetamine misuse and a single case after ecstasy misuse.10,13 The growing pandemic of cocaine use in Western society is providing increasing evidence of its association with intracerebral haemorrhage.14–19 It is becoming increasingly evident that misuse of cocaine in people with underlying vascular abnormalities may lead to haemorrhage.

Cases and outcomes

In the past seven months we have treated 13 patients who had sustained intracerebral haemorrhage and had misused one or more of these illegal substances. Ten of the patients were well enough to undergo cerebral angiography. We were surprised to find intracranial aneurysm in six and arteriovenous malformations in three. In only one patient was the angiogram normal. These nine patients subsequently underwent surgery or interventional radiological treatment for these abnormalities. The average age of the 13 patients was 31 years (range 19-43 years).

Surgery was successful in four of the six patients with intracranial aneurysm, and they were discharged home with no neurological deficits. One patient was discharged home with a residual hemiplegia, and one patient died before treatment. Of the three patients with arteriovenous malformations, one underwent successful surgical treatment, one had successful coil embolisation, and one, who had severe neurological impairment after surgery, was referred for long term rehabilitation. The three patients who were not fit enough for angiography died. One of these was shown to have a middle cerebral artery aneurysm at necropsy examination.

ANGELA SMITH

Discussion

Epidemiology

Drug misuse has been identified in The Health of the Nation20 as a major problem that requires attention because of its link with HIV infection and its strong correlation with material deprivation.21 Accurate epidemiological data on the extent of the problem is difficult to collect. However, in 1988, during a study carried out in six major Spanish cities, acute drug reactions were responsible for 11% of all deaths in people aged 15-39 years.22

Illegal use of cocaine in its various forms has reached epidemic proportions in the United States and the United Kingdom. An estimated 25-30 million Americans have used cocaine, and 5-6 million use it regularly.23 A study from Grady Hospital in Atlanta found that 39% of 415 male patients who presented themselves to the triage desk for immediate care during weekdays tested positive for benzoylecgonine, the primary metabolite of cocaine.24 The average age of these patients was 29.5 years (range 18-39 years).

Neurological complications

A recent paper described patients who died from non-traumatic brain haemorrhage and underwent necropsy examination at the Connecticut office of the chief medical officer over a one year period.25 Fifty nine per cent of the patients were positive for cocaine. Seventy per cent of the patients who had taken cocaine had an intracerebral haemorrhage; the remainder had a subarachnoid haemorrhage associated with a berry aneurysm. In 1989 and 1990, cocaine ranked first in terms of total encounters, major medical complications, and drug related deaths.26

Ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine), a synthetic amphetamine derivative, has become increasingly popular in recent years. In the United Kingdom, use of ecstasy has become an inherent part of “dance culture” for the young.27

The association between intracerebral haemorrhage and the use of amphetamines and related compounds is increasingly recognised.2–10 Intracerebral haemorrhage can occur after a single dose and after therapeutic use as well as after misuse. However, doctors must be aware that it is difficult to link any neurological event with use of a particular drug. This is because patients may give inaccurate histories or because the substances bought on the street are frequently mixed with a variety of compounds before they are sold.

Brust and Richter first reported neurovascular complications of cocaine in 1977.14 In 1984, Lichtenfeld et al reported two cases of subarachnoid haemorrhage after cocaine use, and these authors were the first to report the finding of an underlying abnormality of the cerebral vasculature.15 Mangiardi et al reported a further nine cases.16 In their series, arteriography detected one patient with a cerebral aneurysm and two with arteriovenous malformations.16 Fessler et al found that all 12 patients who underwent cerebral angiography after sustaining a subarachnoid haemorrhage secondary to cocaine abuse were subsequently found to have intracerebral aneurysms.19 The diameter of the aneurysm in cocaine users averaged 4.9 mm, while that in control subjects was 11 mm. In addition, the average age at presentation of the cocaine users with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage was 32.8 years, whereas the patients in the control group averaged 52.2 years. Oyesiku has recently estimated that the incidence of ruptured intracranial aneurysms in patients with cocaine induced subarachnoid haemorrhage is as high as 85%.18 Intracerebral haematomas related to arteriovenous malformations, ischaemic strokes, and reversible ischaemic neurological deficits have all been reported after cocaine ingestion.19

Cocaine and amphetamine misuse are both well recognised causes of subarachnoid haemorrhage; we are aware of only one other report linking subarachnoid haemorrhage to ecstasy.28 Despite the widespread use of ectasy, acute neurological complications from it seem to be rare.29

Cerebral angiitis has been reported to occur with amphetamine misuse.2,3,6–10 Citron et al reported 14 cases of necrotising angiitis related to drug misuse.11 The radiological manifestations of these abnormalities have been reported after angiography—there is pronounced irregularity and “beading” in the middle and anterior cerebral arterial branches after methamphetamine is given intravenously.2,5,30

Cocaine rarely, if ever, causes frank vasculitis.17 The main mechanism of action proposed is the hypertensive surge recorded after its administration.15–719,25 Cocaine induces vasospasm and potential ischaemia by direct effects on smooth muscle and by augmenting the physiological effects of catecholamines.31 This may be potentiated by enhanced platelet aggregation caused by cocaine's increased thromboxane production.32

A similar acute sympathetic surge has also been postulated as the cause of aneurysm rupture after taking ecstasy. Repeated use of the drug may cause recurrent surges in blood pressure that lead to a progressive weakening of the vessel wall and result in aneurysm instability. However, since ecstasy is a synthetic amphetamine derivative, it probably causes a degree of cerebral vasculitis too.

Prognosis

The mortality and morbidity of patients who sustain intracerebral haemorrhage after substance misuse seem to be appreciably greater than those in similar patients who do not use illegal drugs.33 One explanation for this is that the intensity and duration of vasospasm is worsened by the use of cocaine.15 Another is that the initial grade of haemorrhage at the time of admission to hospital is also generally more serious in these patients. This usually reflects the fact that they are neglected in the initial phase of their illness. These patients often present to hospital in a dehydrated state and with serious underlying illness such as AIDS and malnutrition.

Conclusions

Contrary to past opinion, drug related intracerebral haemorrhage often seems to be related to an underlying vascular malformation. A history of severe headache immediately after using amphetamine, ecstasy, or cocaine should alert doctors to the possibility of intracerebral haemorrhage. Cerebral computed tomography should always be performed when severe headache or altered consciousness, or both, occur in relation to use of these compounds. Arteriography should be part of the evaluation of most young patients with non-traumatic intracerebral haemorrhage. Long term use of cocaine seems to predispose patients with incidental neurovascular anomalies to present at an earlier point than similar non- users of cocaine. A thorough medical history focusing on the use of illegal drugs and toxicological screening of urine and serum should be part of the evaluation of any young patient with a stroke.

In young people with haemorrhagic stroke, think of drug misuse and look for an underlying vascular cause

Footnotes

Funding: No additional funding.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Gericke OL. Suicide by ingestion of amphetamine sulphate. JAMA. 1945;128:1098–1099. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Margolis MT, Newton TH. Methamphetamine (“speed”) arteritis. Neuroradiology. 1971;2:179–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00335049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yarnell PR. “Speed”: headache and hematoma. Headache. 1977;17:69–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delaney P, Estes M. Intracranial hemorrhage with amphetamine abuse. Neurology. 1980;30:1125–1128. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.10.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cahill DW, Knipp H, Mosser J. Intracranial hemorrhage with amphetamine abuse [letter] Neurology. 1981;31:1058–1059. doi: 10.1212/wnl.31.8.1058-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrington H, Heller HA, Dawson D, Caplan L, Rumbaugh C. Intracerebral hemorrhage and oral amphetamine. Arch Neurol. 1983;40:503–507. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1983.04210070043012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salanova V, Taubner R. Intracerebral haemorrhage and vasculitis secondary to amphetamine use. Postgrad Med J. 1984;60:429–430. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.60.704.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toffol GJ, Biller J, Adams-HP J. Nontraumatic intracerebral hemorrhage in young adults. Arch Neurol. 1987;44:483–485. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1987.00520170013014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibata S, Mori K, Sekine I, Suyama H. Subarachnoid and intracerebral hemorrhage associated with necrotizing angiitis due to methamphetamine abuse—an autopsy case. Neurol Med Chir Tokyo. 1991;31:49–52. doi: 10.2176/nmc.31.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selmi F, Davies KG, Sharma RR, Neal JW. Intracerebral haemorrhage due to amphetamine abuse: report of two cases with underlying arteriovenous malformations. Br J Neurosurg. 1995;9:93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Citron BP, Halpern M, McCarron M, Lundberg GD, McCormick R, Pincus IJ, et al. Necrotizing angiitis associated with drug abuse. N Engl J Med. 1970;283:1003–1011. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197011052831901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aggarwal SK, Williams V, Levine SR, Cassin BJ, Garcia JH. Cocaine-associated intracranial hemorrhage: absence of vasculitis in 14 cases. Neurology. 1996;46:1741–1743. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.6.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lukes SA. Intracerebral hemorrhage from an arteriovenous malformation after amphetamine injection. Arch Neurol. 1983;40:60–61. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1983.04050010080027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brust JC, Richter RW. Stroke associated with cocaine abuse—? N Y State J Med. 1977;77:1473–1475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lichtenfeld PJ, Rubin DB, Feldman RS. Subarachnoid hemorrhage precipitated by cocaine snorting. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:223–224. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1984.04050140125041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangiardi JR, Daras M, Geller ME, Weitzner I, Tuchman AJ. Cocaine-related intracranial hemorrhage. Report of nine cases and review. Acta Neurol Scand. 1988;77:177–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1988.tb05891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levine SR, Brust JC, Futrell N, Ho KL, Blake D, Millikan CH, et al. Cerebrovascular complications of the use of the “crack” form of alkaloidal cocaine [comment] N Engl J Med. 1990;323:699–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199009133231102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oyesiku NM, Colohan AR, Barrow DL, Reisner A. Cocaine-induced aneurysmal rupture: an emergent factor in the natural history of intracranial aneurysms? Neurosurgery. 1993;32:518–525. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fessler RD, Esshaki CM, Stankewitz RC, Johnson RR, Diaz FG. The neurovascular complications of cocaine. Surg Neurol. 1997;47:339–345. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(96)00431-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Secretary of State for Health. The health of the nation. London: HMSO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Squires NF, Beeching NJ, Schlecht BJ, Ruben SM. An estimate of the prevalence of drug misuse in Liverpool and a spatial analysis of known addiction. J Public Health Med. 1995;17:103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez J, Rodriguez B, de-la-Fuente L, Barrio G, Vicente J, Roca J, et al. Opiates or cocaine: mortality from acute reactions in six major Spanish cities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49:54–60. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kloner RA, Hale S, Alker K, Rezkalla S. The effects of acute and chronic cocaine use on the heart. Circulation. 1992;85:407–419. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.2.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNagny SE, Parker RM. High prevalence of recent cocaine use and the unreliability of patient self-report in an inner-city walk-in clinic. JAMA. 1992;267:1106–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nolte KB, Brass LM, Fletterick CF. Intracranial hemorrhage associated with cocaine abuse: a prospective autopsy study. Neurology. 1996;46:1291–1296. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.5.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benowitz NL. How toxic is cocaine? Ciba Foundation Symposium. 1992;166:125–143. doi: 10.1002/9780470514245.ch8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henry JA. Ecstasy and the dance of death. BMJ. 1992;305:5–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6844.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gledhill JA, Moore DF, Bell D, Henry JA. Subarachnoid haemorrhage associated with MDMA abuse [letter] J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56:1036–1037. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.9.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peroutka SJ. Incidence of recreational use of 3,4-methylenedimethoxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) on an undergraduate campus [letter] N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1542–1543. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712103172419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rumbaugh CL, Bergeron RT, Fang HC, McCormick R. Cerebral angiographic changes in the drug abuse patient. Radiology. 1971;101:335–344. doi: 10.1148/101.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caplan L. Intracerebral hemorrhage revisited. Neurology. 1988;38:624–627. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Togna G, Tempesta E, Togna AR, Dolci N, Cebo B, Caprino L. Platelet responsiveness and biosynthesis of thromboxane and prostacyclin in response to in vitro cocaine treatment. Haemostasis. 1985;15:100–107. doi: 10.1159/000215129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simpson RKJ, Fischer DK, Narayan RK, Cech DA, Robertson CS. Intravenous cocaine abuse and subarachnoid haemorrhage: effect on outcome. Br J Neurosurg. 1990;4:27–30. doi: 10.3109/02688699009000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]