Abstract

Retroviral reverse transcriptase (RT) enzymes are responsible for transcribing viral RNA into double-stranded DNA. An in vitro assay to analyze the second strand transfer event during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcription has been developed. Model substrates were constructed which mimic the viral intermediate found during plus-strand strong-stop synthesis. Utilizing wild-type HIV-1 RT and a mutant E478Q RT, the requirement for RNase H activity in this strand transfer event was analyzed. In the presence of Mg2+, HIV-1 RT was able to fully support the second strand transfer reaction in vitro. However, in the presence of Mg2+, the E478Q RT mutant had no detectable RNase H activity and was unable to support strand transfer. In the presence of Mn2+, the E478Q RT yields the initial endoribonucleolytic cleavage at the penultimate C residue of the tRNA primer yet does not support strand transfer. This suggests that subsequent degradation of the RNA primer by the RNase H domain was required for strand transfer. In reactions in which the E478Q RT was complemented with exogenous RNase H enzymes, strand transfer was supported. Additionally, we have shown that HIV-1 RT is capable of supporting strand transfer with substrates that mimic tRNAHis as well as the authentic tRNA3Lys.

Reverse transcription is a multistep process which converts the retroviral RNA genome into double-stranded DNA. Reverse transcription is carried out by the multifunctional enzyme reverse transcriptase (RT), possessing RNA- and DNA-dependent DNA polymerase and RNase H activities. For human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), RT consists of an asymmetric heterodimer of two subunits, p66 and p51. The p66 subunit contains the subdomains named finger, palm, thumb, connection, and RNase H, based on the structural similarity to a hand (2, 16, 22). The p51 subunit lacks the RNase H domain at the C terminus and results from a protease cleavage between phenylalanine 440 and tyrosine 441 of p66 (23).

A great deal of research has focused on characterization of the domains of HIV-1 RT and their interrelations. The three-dimensional structure of the p66-p51 heterodimer reveals a template-primer cleft which connects the polymerase and RNase H active sites. Mutations outside of the RNase H catalytic domain can affect RNase H activity indirectly if they alter the positioning of the RNA or DNA substrate. For example, mutations within the palm (primer grip region within the p66 subunit; residues 227 to 235) (12, 32), finger, and thumb subdomains (14) have been identified with decreased RNase H activity. Deletion of amino acids from the p51 subunit have also been shown to alter RNase H cleavage (5). Interestingly, a mutation in the finger subdomain has been identified which stimulates minus-strand transfer in vitro (14).

The catalytic triad of the RNase H domain consists of Asp 443, Glu 478, and Asp 498 (10, 11, 37). These residues are important for metal binding, and mutation of a single residue of the triad renders the RNase H subunit inactive. Studies of an E478Q mutant RT have shown that RNase H activity can be modulated by different divalent metal cations (7). In the presence of manganese, the mutant enzyme is capable of a single endoribonucleolytic cleavage by RNase H but is incapable of subsequent degradation of the RNA template (7).

Reverse transcription first requires initiation by a tRNA primer, which binds to the primer binding site (PBS) on the viral RNA (24). The tRNAs utilized are characteristic of the particular retrovirus; HIV-1 utilizes tRNA3Lys (21), avian myeloblastosis virus utilizes tRNATrp, and Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MuLV) utilizes tRNAPro. HIV-1 RT can utilize primers other than tRNA3Lys with decreased kinetics of infection (43, 44), which require mutations within the viral genome and within the first 18 nucleotides of the tRNA primer and upstream in the A-rich loop (17). Minus-strand DNA synthesis then proceeds to the 5′ end of the viral RNA; the reverse-transcribed viral RNA is degraded by RNase H, and the first strand transfer occurs. Plus-strand synthesis is initiated from the polypurine tract and terminates after reverse transcribing the first 18 nucleotides of the tRNA primer. The tRNA primer is specifically removed by RNase H (33, 39, 41), and the second strand transfer occurs through the duplication of the PBS region.

In addition to the strand transfer reactions involving strong-stop DNAs, internal strand transfers also occur during DNA synthesis steps. Investigation of internal strand transfer during RNA-directed DNA synthesis revealed a requirement for RNase H activity and was favorable during RT pausing (9). However, strand transfer reactions between DNA templates and primers do not require RNase H activity (13, 30).

We have developed an in vitro assay to analyze the second strand transfer reaction during HIV-1 reverse transcription. Model substrates were constructed which mimic the intermediate resulting from plus-strand strong-stop DNA synthesis. This system allows for analysis of intermediate steps required for strand transfer, such as DNA polymerization, pause sites, RNase H activity, and transfer to an acceptor DNA molecule. We have shown with an RNase H-defective mutant, E478Q, that RNase H activity is required for the second strand transfer reaction. More specifically, we have determined that directional processing or polymerase-independent cleavages by RNase H are required for this strand transfer reaction. The E478Q RT can support strand transfer when it is complemented with Escherichia coli RNase H in trans. Additionally, we have shown that HIV-1 RT is capable of supporting strand transfer with a model substrate which mimics tRNAHis and an authentic tRNA3Lys substrate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Enzymes and nucleotides.

T4 polynucleotide kinase was purchased from New England Biolabs; recombinant RNasin was purchased from Promega. Exonuclease(−) Klenow polymerase was purchased from United States Biochemical. HIV-1 RT was obtained from Jeffrey Culp and Christine Debouch, Department of Protein Biochemistry, SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals. HIV-1 RT (E478Q mutant) was obtained from Stuart F. Le Grice and the AIDS repository (contributor, Stuart F. Le Grice). M-MuLV was purified from E. coli containing the plasmid pB6B15.23 (36). Isolate HIV-1 RNase H (NY427) was purified from E. coli containing the plasmid pET-NY427 (40). E. coli RNase H was purchased from Gibco BRL. [γ-32P]ATP was purchased from ICN. Authentic tRNA3Lys purified from human placenta was purchased from Bio S & T Inc.

Oligonucleotides.

The RNA oligonucleotide HPR-1, 5′ GUCCCUGUUCGGGCGCCA 3′ was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. The RNA oligonucleotide mimicking tRNAHis, 5′ AUCCGAGUCACGGCACCA 3′, was purchased from CyberSyn. The DNA oligonucleotides 5785, 5′ CCCTCAGACCCTTTTAGTCAGTGTGG 3′; 5786, 5′ CCCTTTTAGTCAGTGTGGAAAATCTCAGCAGTGGCGCCCGAACAGGGAC 3′; 5580, 5′ TTTCGCTTTCAGGTCCCTGTTCGGGCGCCA 3′; 9142, 5′ CTGCTAGAGATTTTCCACACTGACTAAAAGGG 3′; 9243, 5′ TTTCGCTTTCAGATCCGAGTCACGGCACCA 3′; and 9245, 5′ CCCTTTTAGTCAGTGTGGAAAATCTCTAGCAGTGGTGCCGTGACTCGGAT 3′ were synthesized by the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey.

Strand transfer substrate preparation.

The 50-mer input RNA-DNA hybrid substrate was prepared as follows. Twenty picomoles of the 18-mer RNA (HPR-1), was 5′ labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. The radiolabeled RNA was isolated with G-25 spin columns (Boehringer Mannheim). The labeled substrate was annealed to 40 pmol of oligonucleotide 5786 in a 25-μl reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM KCl, 8 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM dithiothreitol. The substrate was extended with Klenow Exonuclease(−), gel isolated, and eluted overnight as previously described (38). The substrate was then annealed to oligonucleotide 5785 (referred to as 26-mer). This oligonucleotide was also 5′ labeled, in the same manner as described for HPR-1. The RNA oligonucleotide which mimics tRNAHis was prepared in the manner described above, utilizing oligonucleotide 9245 as an extension template to construct the RNA-DNA oligonucleotide.

The authentic tRNA3Lys substrate was ligated to the U5 sequences in the presence of a bridging oligonucleotide (26). Oligonucleotide 9142 was 5′ labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. The radiolabeled DNA was isolated with G-25 spin columns (Boehringer Mannheim). The DNA oligonucleotide (9142) and authentic tRNA3Lys were annealed to oligonucleotide 5786 in a reaction containing 200 mM KCl and 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5. After annealing, the authentic tRNA3Lys and DNA oligonucleotide were ligated with T4 DNA ligase in a reaction containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM ATP, and 25 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml. The tRNA3Lys-DNA oligonucleotide was gel isolated and eluted overnight as previously described (38). The tRNA3Lys-DNA oligonucleotide was annealed to oligonucleotide 5785, which was also 5′ labeled as described above. Control experiments which contain 18-mer RNA-DNA (9142) oligonucleotide substrates were prepared in the same manner.

Strand transfer reactions.

The annealed RNA-DNA hybrid substrate was incubated with either HIV-1 RT or E478Q RT. The strand transfer reactions were performed in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing approximately 4 pmol of substrate (substrate refers to the 50-mer RNA-DNA hybrid annealed to primer 5785); 4 pmol of acceptor (oligonucleotide 5580); 2 pmol of either HIV-1 RT or E478Q RT in a reaction buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 8 mM MgCl2, or 8 mM MnCl2; and 0.25 mM each deoxynucleotide (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and TTP). The reactions were initiated upon the addition of enzyme and incubated at 37°C. Aliquots (2.5 μl) were removed at the indicated time points. Reaction products were separated on a 15% denaturing gel and detected by autoradiography.

For experiments in which two divalent cations were utilized (Mg2+ and Mn2+), the reaction mixture contained 8 mM MgCl2; MnCl2 was added to a final concentration of 8 mM after the 10-min time point. In reactions in which multiple enzymes were used, such as E. coli RNase H, HIV-1 RT, and NY 427, 2 pmol of the additional enzyme was added after the 10-min time point.

For experiments in which authentic tRNA3Lys was utilized, reactions were performed in the presence of 1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) and 8.5 pmol of HIV-1 RT was utilized. For experiments utilizing tRNAHis, oligonucleotide 9243 was used as the acceptor molecule.

RESULTS

Second strand transfer assay.

We have developed an in vitro assay for analyzing the second strand transfer reaction with model RNA-DNA hybrid substrates which mimic the intermediate found during plus-strand strong-stop synthesis. The model assay is represented in Fig. 1. The 50-mer RNA-DNA hybrid was constructed by 5′ labeling an 18-mer RNA oligonucleotide with [γ-32P]ATP. The RNA primer was gel purified after being labeled and was annealed to a 50-mer DNA oligonucleotide which was complementary with the 18 nucleotides of the RNA primer. Once annealed, the RNA primer was extended with Klenow [Exonuclease(−)] polymerase. The extended 50-mer RNA-DNA oligonucleotide was then annealed to the 26-mer DNA primer (5785), which was also 5′ labeled. This substrate mimics an intermediate formed during plus-strand strong-stop synthesis (Fig. 1, step 1). This substrate was incubated with either HIV-1 RT or a mutant E478Q RT (Fig. 1, step 2). In the presence of wild-type HIV-1 RT, nucleotides, and magnesium, DNA polymerization occurs and the primer 5785 was extended to a 58-mer, utilizing the 50-mer RNA-DNA oligonucleotide as a template. Termination of synthesis in this assay occurs at the 5′ end of the RNA. This site mimics the product formed in vivo, where termination on the tRNA template occurs at the modified base, methyl-adenosine 58 (25, 35). DNA polymerization with the tRNA as a template generates an RNA-DNA hybrid which is a substrate for RNase H. HIV-1 RNase H removed the RNA primer, with the initial cleavage occurring between the terminal A ribonucleotide and C ribonucleotide (41), yielding a 17-mer product (Fig. 1, step 3) and was followed by subsequent degradation of the RNA. The 50-mer RNA-DNA oligonucleotide may also be extended at its 3′ OH to produce a 58-mer. Since the 5′ terminus from the RNA was labeled, identical RNase H cleavage products would be detected from either the 50-mer or 58-mer. For strand transfer to occur, the acceptor molecule must enter and serve as a template for elongation (Fig. 1, step 4). The acceptor molecule (5580) was complementary to the plus-strand strong-stop DNA. This strand transfer event would result in the production of a 70-mer product. The acceptor molecule can serve as a primer for reverse transcription; however these products are not radiolabeled and would not be detected in the assay.

FIG. 1.

Assay for second strand transfer. The assay to analyze the second strand transfer reaction is shown. The model 50-mer RNA-DNA oligonucleotide which mimics the viral intermediate is illustrated. The RNA portions are indicated by boldface. The 26-mer DNA (5785) primer is complementary to the 3′ terminus of the RNA-DNA oligonucleotide (step 1). The 50-mer RNA-DNA oligonucleotide and the 26-mer are both (*) 32P radiolabeled at their 5′ termini. Step 2 illustrates the substrate incubated in the presence of dNTPs and HIV-1 RT; DNA polymerization yields a 58-mer extension product. Step 3 illustrates removal of the RNA primer by the RNase H domain, which results in the production of a 17-mer radiolabeled RNA product. Step 4 shows the events which occur in the presence of the acceptor molecule (5580); a 70-mer strand transfer product is produced.

Analysis of the tRNA removal with an avian virus indicated the tRNA was removed as an intact species (27). In contrast, minus-strand transfer for HIV-1 requires degradation of the RNA within the hybrid (30). This study develops an in vitro model system for the second strand transfer which allows for systematic analysis of the requirements of DNA polymerization, RNase H cleavage and degradation, and utilization of the acceptor molecule.

The second strand transfer reaction with HIV-1 RT.

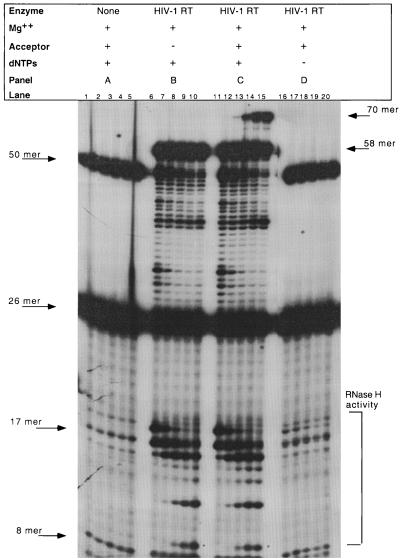

Studies were initiated which analyzed the second strand transfer reaction with HIV-1 RT. The reaction conditions for HIV-1 RT-catalyzed strand transfer were established as shown in Fig. 2. Each panel represents a time course reaction between 30 s and 30 min. Figure 2A represents the reaction in the absence of enzyme, where the input 50-mer RNA-DNA strand and the 26-mer, DNA primer (5785) for DNA synthesis, are detected. Minor breakdown products at approximately 16 and 7 nucleotides were detected in the starting substrates; however, no additional products were detected throughout the incubation period. Reactions in the presence of enzyme and the absence of dNTPs yielded similar species (Fig. 2D). In the presence of dNTPs, DNA synthesis occurred, yielding a 32P-labeled 58-mer product which was an RNA-DNA hybrid (Fig. 2B). Simultaneous with the production of the extension product (58-mer) was the degradation of the 58-mer by RNase H, yielding 5′-end-labeled RNA products, the largest of which was the 17-mer. The 17-mer was produced after cleavage between the C and A at the 3′ end of the RNA. Within 30 s, a 58-mer extension product and the 17-mer RNase H cleavage product were detectable (Fig. 2B, lane 6). Figure 2C shows the complete reaction in the presence of dNTPs, Mg2+, and acceptor. The second strand transfer product (70-mer) was observed at 5 min (Fig. 2C, lane 13). This correlated with the production of smaller RNase H products of approximately 8 or 9 bases (Fig. 2C, lane 13).

FIG. 2.

HIV-1 RT assayed in the model in vitro system. Reactions were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Time points for each set of reactions are 0.5, 2, 5, 15, and 30 min (lanes 1 to 5, 6 to 10, 11 to 15, and 16 to 20, respectively). The presence or absence of acceptor, dNTPs and metal is indicated by a + or − sign, respectively. The enzyme utilized is indicated above each panel. Input RNA-DNA oligonucleotide (50-mer), DNA primer (26-mer), extension products (58-mer), strand transfer product (70-mer), and RNase H products (17-mer and 8-mer) are indicated with arrows based on the size of the species. An asterisk indicates the 8-mer in panels B and C.

Second strand transfer reactions with E478Q RT.

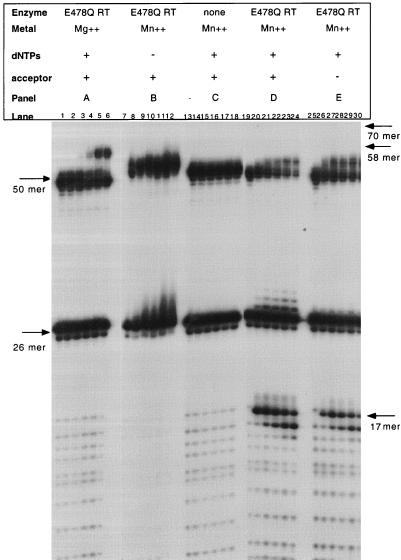

E478Q RT is an endoribonuclease in the presence of manganese and lacks all RNase H activity in the presence of magnesium. This mutant is also unable to perform directional processing of the RNA primer (7). Utilizing this mutant RT in the assay allows for the manipulation of the RNase H cleavages that are required to support strand transfer. Figure 3 represents the time course reactions between 0 and 30 min for strand transfer performed with E478Q RT. Figure 3A illustrates a strand transfer reaction performed in the presence of Mg2+ with the RNase H mutant RT E478Q. In the presence of Mg2+, as previously characterized for the wild-type enzyme, the input 50-mer and 26-mer substrates were detected. In addition, the 58-mer extension product was observed but no RNase H cleavage and strand transfer products were detected.

FIG. 3.

E478Q RT assayed in the in vitro plus-strand transfer assay. Reactions were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The time points for each set of reactions are 0, 0.5, 2, 5, 15, and 30 min (lanes 1 to 6, 7 to 12, 13 to 18, 19 to 24, and 25 to 30, respectively). The presence or absence of acceptor and dNTPs, is indicated by a + or − sign, respectively. The enzyme and metal utilized are indicated above each panel. Input substrates and reaction products are indicated by arrows.

Figure 3B shows a strand transfer reaction utilizing E478Q RT performed in the presence of manganese and in the absence of nucleotides. As expected, only the input 50-mer RNA-DNA hybrid and the 26-mer DNA primer are detected. Figure 3C shows the strand transfer reaction in the presence of manganese, without enzyme. The results are similar to those in Fig. 3B, except that a low level of background nonspecific degradation of the RNA can be detected upon the addition of nucleotides. Figure 3D shows a complete E478Q RT reaction performed in the presence of Mn2+, dNTPs, and acceptor. Figure 3E is similar except that it lacks the acceptor strand, 5580. In the presence of acceptor, no strand transfer product was detected. The extension reaction was very poor in the presence of Mn2+ (Fig. 3D and E) compared with that observed in the presence of Mg2+ (Fig. 3A). In fact, a full-length extension product (58-mer) was not observed in these reactions. However, an extension product was observed which does create an RNA-DNA hybrid throughout at least 12 nucleotides of the tRNA primer. With this partial extension, RNase H cleavage proceeds, with the production of the 17-mer product. Furthermore, a low level of −2 cleavage products was detected with the E478Q RT over the time course of the reaction (Fig. 3D and E).

Strand transfer reaction performed in the presence of two divalent cations.

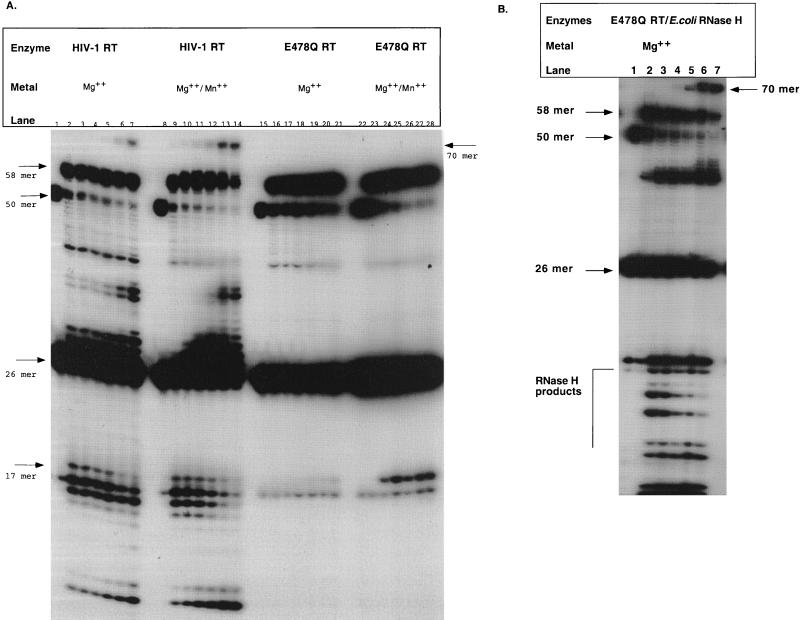

The initial experiments described above showed that the DNA polymerization event for E478Q RT was more efficient in the presence of magnesium than in the presence of manganese, but manganese was required for RNase H activity. To test the possibility that strand transfer requires full synthesis of the plus-strand strong stop, reactions were performed in the presence of both divalent cations. In Fig. 4A, the synthesis in the presence of Mg2+ alone was compared to synthesis with both Mg2+ and Mn2+ combined. This was analyzed with the wild-type HIV-1 RT (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 to 14) and the E478Q HIV-1 RT (lanes 15 to 28). The reactions were initially incubated in the presence of magnesium. After 10 min (lanes 2, 9, 16, and 23), manganese was added to the indicated reactions, and they were allowed to proceed for up to 40 min. For wild-type HIV-1 RT (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 to 7), an extension product (58-mer), RNase H cleavage products, and a strand transfer product (70-mer) were observed. However, for E478Q RT, only a 58-mer extension product was observed. In the presence of both divalent cations (Fig. 4A, lanes 8 to 14), HIV-1 RT’s strand transfer ability was unaffected. For E478Q RT (Fig. 4A, lanes 22 to 28), at the 10-min time point prior to Mn2+ addition, an extension product was observed (Fig. 4A, lane 23), but no RNase H activity was observed. Once manganese was added (Fig. 4A, lane 24) the single endoribonucleolytic RNase H cleavage event occurred, producing the 17-mer RNA. However, strand transfer did not occur throughout the remainder of the time course (Fig. 4A, lanes 22 to 28). Separate time courses have been performed up to 1 h, and no strand transfer was observed for the E478Q HIV-1 RT. This result indicates that synthesis of plus-strand strong-stop DNA followed by a single endoribonucleolytic cleavage was not sufficient by itself to induce strand transfer.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of E478Q RT in the presence of two divalent cations and complementation with E. coli RNase H. (A) Time course reactions of E478Q RT assayed in the presence of Mg2+ or Mn2+ and Mg2+ are shown. The reactions were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Addition of Mn2+ occurred after the 10-min time point. The metal present is indicated above each panel. Time points for each set of reactions are 0, 10, 10.5, 12, 15, 25, and 40 min (lanes 1 to 7, 8 to 14, 15 to 21, and 22 to 28, respectively). (B) E478Q RT complemented with E. coli RNase H is shown. The reaction was performed as described in Materials and Methods. E. coli RNase H was added after the 10-min time point. Lanes 1 to 7 represent 0, 10, 10.5, 12, 15, 25, and 40 min, respectively. Input RNA-DNA (50-mer), 26-mer DNA primer, extension products (58-mer), RNase H cleavage products (17-mer and smaller), and strand transfer products (70-mer) are indicated by arrows.

Complementation of E478Q RT with exogenous RNase H enzymes.

The single endoribonucleolytic cleavage was not sufficient to support the second strand transfer reaction for the E478Q RT. Additional studies were therefore performed to investigate whether the lack of strand transfer resulted from an RNase H defect or from a secondary effect on the polymerase domain. The E478Q RT was complemented with various exogenous RNase H enzymes to determine whether directional processing or additional cleavages of the RNA primer by RNase H would support strand transfer (Fig. 4B).

The substrate was initially incubated for 10 min in the presence of E478Q RT, nucleotides, acceptor, and magnesium. After this time point, an exogenous RNase H enzyme was added. The reaction was performed in the presence of magnesium so that all RNase H activity would be a result of the exogenous RNase H. Figure 4B illustrates that E. coli RNase H complemented the strand transfer defect of E478Q RT. Upon addition of E. coli RNase H, RNase H cleavage products quickly accumulated (Fig. 4B, lane 3), followed by the production of a strand transfer product after 15 min (Fig. 4B, lane 5). The E. coli complementation also degrades the RNA much more extensively than HIV-1 RT (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 to 7, and data not shown), indicating a correlation with RNase H and strand transfer activities. Complementation of E478Q RT with an isolated RNase H domain, NY427, was also examined. This isolated RNase H domain similarly yields a single endoribonucleolytic cleavage at the same position as E478Q RT and was Mn2+ dependent (40). Complementation of E478Q RT with NY427 did not result in any strand transfer, indicating that subsequent degradation of the primer was required for strand transfer (data not shown). Furthermore, these results indicate that complete removal of the tRNA by RNase H activity was critical for plus-strand transfer.

Analysis of plus-strand transfer with authentic tRNA3Lys substrate.

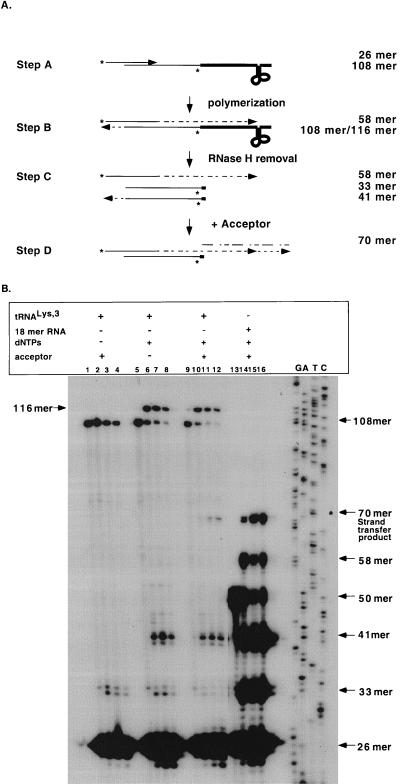

Since HIV-1 RT was capable of supporting strand transfer with a substrate mimicking tRNA3Lys, it was of interest to determine whether the additional secondary structure associated with the authentic tRNA3Lys affected strand transfer. The substrates utilized are shown in Fig. 5A, step A. The 108-mer tRNA3Lys-DNA oligonucleotide was constructed by 5′ labeling the 32-mer minus-strand DNA oligonucleotide (9142) and ligating it to the authentic tRNA3Lys (76 nucleotides), utilizing the bridging method as described in Materials and Methods (26). The substrate differs from those used in the previous assays in that the radiolabel was internal. In the presence of nucleotides, the extension product from the 5′-labeled 26-mer plus-strand primer should terminate at the first methylated A of the tRNA (Fig. 5A, step B), yielding a 58-nucleotide product, also produced with the tRNA mimic oligonucleotide. Polymerization from the 3′ OH of the 108-mer tRNA-DNA molecule would also result in the production of a 116-mer product. RNase H cleavage (Fig. 5B, step C) would release a radiolabeled DNA product and an unlabeled tRNA. RNase H cleavage between the terminal C ribonucleotide and A ribonucleotide of the 108-mer tRNA-DNA strand would produce a 33-mer labeled DNA product; cleavage of the alternative 116-mer extended product would release a 41-mer product (Fig. 5A, step C). The strand transfer product was a 70-mer, as in the previous assay with the oligoribonucleotide mimic (Fig. 5A, step D).

FIG. 5.

Strand transfer reactions performed with authentic tRNA3Lys. (A) The assay to analyze the second strand transfer reaction with authentic tRNA3Lys substrates is shown. Substrate was prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Step A illustrates the input substrate, a 26-mer DNA primer annealed to the 108-mer tRNA3Lys-DNA. An asterisk indicates the location of the 5′ label. Step B shows the substrate incubated in the presence of dNTPs and HIV-1 RT; DNA polymerization yields a 58-mer extension product. Polymerization can also proceed in the opposite direction, yielding a 116-mer. Step C illustrates the removal of the tRNA primer and the production of a 33-mer radiolabeled DNA product after RNase H cleavage. Cleavage of the 116-mer extension product would yield a 41-mer radiolabeled DNA product. Step D shows the presence of an acceptor molecule (5580); a 70-mer strand transfer product results. (B) Time course reactions of authentic tRNA3Lys assayed with HIV-1 RT are shown. The reactions were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The reaction components are indicated above each lane. Lanes 1 to 4, 5 to 8, and 9 to 12, HIV-1 RT assayed with the authentic tRNA3Lys-DNA oligonucleotide substrate; lanes 13 to 16, HIV-1 RT assayed with 18-mer RNA-DNA oligonucleotide substrate. Product and input substrate sizes are indicated on the right with a DNA ladder. Reaction timepoints are 0, 15, 30, and 60 min for lanes 1 to 4, 5 to 8, 9 to 12, and 13 to 16, respectively.

Figure 5B represents the time course reactions with wild-type HIV-1 RT, comparing the authentic tRNA3Lys-DNA substrates (lanes 1 to 12) and a tRNA mimic-DNA substrate (lanes 13 to 16). For the authentic tRNA3Lys substrate in the absence of dNTPs, no DNA polymerization was observed (Fig. 5B, lanes 1 to 4). However, a low level of RNase H cleavage product (33-mer; Fig. 5B, lanes 2 to 4) was observed. This may be a result of the presence of residual DNA template utilized in substrate preparation. A low level of the bridging oligonucleotide could create an RNA-DNA hybrid which would be cleaved by RNase H when HIV-1 RT was present. When nucleotides were added to the reaction (Fig. 5B, lanes 5 to 8), polymerization occurred. Concomitant with the disappearance of the 108-mer product was the appearance of the 116-mer product and the release of the 41-mer. A very low level of heterogeneous products around the size of the 58-mer strong-stop species could be detected on long exposures (data not shown). This may indicate that termination at the methylated A residue was not uniformly occurring in this in vitro reaction (3, 4). Complete readthrough of the tRNA would result in a 116-mer labeled DNA product. However, it was not believed that the 116-mer product detected was the DNA product produced by complete readthrough of the tRNA. With time, the level of the 116-mer product was reduced, consistent with the removal of the tRNA moiety by RNase H. In addition, strand transfer yielding a 70-mer product would not result if the tRNA was completely reverse transcribed. Upon addition of the acceptor to the reaction, a strand transfer product (70-mer) was observed (Fig. 5B, lanes 9 to 12) which migrates identically to the strand transfer product observed with the tRNA mimic-DNA substrate (Fig. 5B, lanes 13 to 16).

The tRNA mimic-DNA substrate in Fig. 5, similar to the authentic tRNA3Lys substrate, was prepared by ligation in the presence of the bridging oligonucleotide. The input substrate consisted of a 50-mer RNA-DNA minus-strand substrate and a 26-mer plus-strand primer. In the presence of dNTPs, acceptor, and wild-type enzyme, an extension product (58-mer), an RNase H cleavage product (33-mer), and a strand transfer product (70-mer) were observed at the 15-min time point (Fig. 5B, lane 14). The results are comparable to those obtained with substrates prepared with Klenow polymerase (Fig. 2) with the exception that in this substrate preparation, strand separation of the 50-mer RNA-DNA molecule from the bridging oligonucleotide was not complete. Therefore, the RNase H cleavage prior to DNA polymerization could also yield a 41-mer product. Similar intermediates and products were observed with the authentic tRNA3Lys. In addition, the kinetics of the strand transfer reaction of the authentic tRNA was similar to that for the mimic substrate. These results support the use of the oligonucleotide substrates to analyze plus-strand transfer reactions.

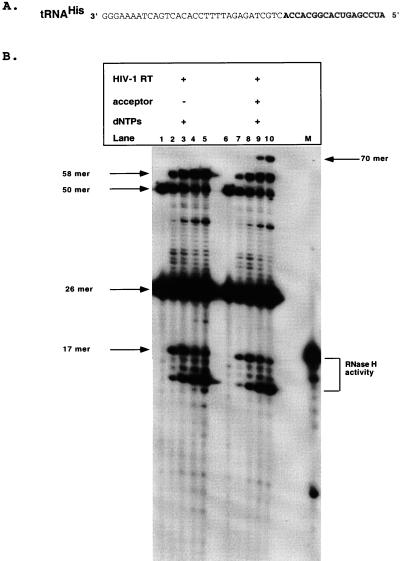

Analysis of strand transfer activity of tRNAHis with HIV-1 RT.

Recent studies have characterized the ability of HIV-1 RT to utilize tRNA primers other than tRNA3Lys to initiate reverse transcription (17, 18, 43, 44). Modified viruses with alterations in the PBS and U5 regions have been generated which can support utilization of an alternative tRNA as the minus-strand primer, particularly tRNAHis and tRNAMet. The consequences of using these alternative tRNAs for primer removal has not been examined. Since an A at position 4 was tolerated in tRNA3Lys mimic substrate, it was predicted that HIV-1 RNase H should also direct the efficient removal and subsequent strand transfer of a tRNAHis substrate (39). Substrates were therefore constructed which substituted the tRNA3Lys mimic sequences with those of tRNAHis (Fig. 6A). Acceptor molecules were complementary to the novel tRNA used, paralleling the mutations in the PBS within the viral genome required in vivo. The strand transfer assay is shown in Fig. 6B. In the absence of acceptor molecules, the tRNAHis model substrate produces an extension product (58-mer) and an initial −1 RNase H cleavage product (17-mer), followed by subsequent RNase H degradation (Fig. 6B, lanes 1 to 5). Upon the addition of an acceptor molecule, a strand transfer product was observed for the tRNAHis model substrate (Fig. 6B, lanes 6 to 10). These results indicate that alternative tRNA primers will be tolerated as long as the RNase H cleavage sites are maintained.

FIG. 6.

HIV-1 RT analyzed with RNA oligonucleotide mimicking tRNAHis. (A) Input RNA-DNA oligonucleotide (50-mer) substrate is indicated for tRNAHis. The RNA portion is in bold type. The acceptor molecule utilized in the reactions is complementary to the particular tRNA utilized and is described in Materials and Methods. The expected product sizes are the same as for tRNA3Lys substrates. (B) Time course reactions of HIV-1 RT analyzed with tRNAHis are shown. Lanes 1 to 5 and 6 to 10 represent HIV-1 RT assayed with tRNAHis in the absence (−) or presence (+) of acceptor, respectively. The reactions were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The reaction components are indicated above each lane. An 18-mer RNA marker (M) is shown. Input substrates and products are indicated by arrows. The time points are 0, 2, 5, 15, and 30 min (lanes 1 to 5 and 6 to 10).

DISCUSSION

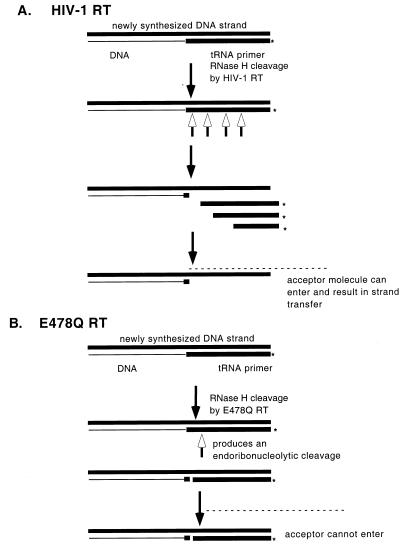

A model system to analyze the second strand transfer event during HIV-1 reverse transcription has been developed. The manipulation of various components of the assay allows for determination of the requirements for DNA polymerization, RNase H activity, and strand transfer. The data shows that HIV-1 RT was capable of supporting plus-strand transfer in the presence of either Mg2+ or Mn2+ (data not shown) as a divalent cation. The E478Q RT RNase H-defective mutant was unable to support strand transfer in the presence of either or both divalent cations. However, in the presence of an exogenous RNase H enzyme, such as E. coli RNase H, strand transfer was supported. This indicates that the specific endoribonucleolytic cleavage catalyzed by E478Q was not sufficient to support plus-strand transfer.

The model in Fig. 7 represents the events which may be occurring and shows the difference between the mechanisms of strand transfer reactions catalyzed by HIV-1 RT and E478Q RT. For both enzymes, the polymerization events are identical (Fig. 7). The differences occur once RNase H activity is required for removal of the tRNA primer. With HIV-1 RT, polymerase-dependent and -independent cleavages and directional processing can occur, which will allow for quick dissociation of the tRNA primer (Fig. 7A). However, the E478Q RT mutant was only capable of producing the endoribonucleolytic cleavage detected by the release of a 17-mer on a denaturing gel. The melting temperature (Tm) of the 17-mer is 60°C, which is greater than the reaction temperature, which would allow it to remain associated with the DNA strand after cleavage (Fig. 7B). Product analysis of the E478Q RNase H cleavage on native gels has shown that a portion of the RNA primer remains annealed to the newly synthesized DNA strand (data not shown). The native product remains susceptible to cleavage by E. coli RNase H, and the RNA primer is therefore not displaced by RT. Mutant RTs with mutations in the pol domain which decrease RNase H activity have also been postulated to be defective in strand transfer because of incomplete removal of the primer (14).

FIG. 7.

Model for second strand transfer reaction. (A) Reaction with HIV-1 RT. (B) Reaction with RNase H mutant E478Q RT. The RNA-DNA hybrid (50-mer), newly synthesized DNA strand (58-mer), and acceptor molecule (5580) are indicated. The asterisks indicate the 5′ labels, the open arrows indicate the sites of RNase H cleavage, and the dashed lines indicate acceptor molecules.

Present research is aimed at understanding the requirements for initiation of reverse transcription with various tRNA primers. Alterations have been made within the PBSs of many retroviral genomes to allow for initiation to occur with the use of alternative primers (17, 18, 28, 43, 44). Little research has focused on the effects these alterations have on RNase H activity or strand transfer. Previous studies have shown that RT-associated RNase H and isolated RNase H enzymes are capable of distinguishing between cognate and noncognate tRNA primers during removal (38, 39). This study investigated the effect of utilizing tRNAHis on strand transfer. tRNAHis has been shown to be utilized on a modified virus (48) and was postulated to function in primer removal (39). The tRNAHis primer was capable of producing a −1 RNase H cleavage product. Subsequent cleavages of the primer were observed. Strand transfer products were produced with kinetics similar to those of the wild-type tRNA3Lys model substrate. Experiments extending these studies to alternative tRNAs which the virus has not been adapted to use are now in progress.

The role of RNase H activity in strand transfer has been investigated in various systems. Early in vitro studies by Peliska and Benkovic demonstrated that with an RNase H-deficient mutant a very limiting amount of minus-strand transfer product was detected (30). Those studies correlated polymerase-independent RNase H cleavage with the strand transfer reaction, when RNase H activity is required. These results are consistent with our findings, in which a plus-strand transfer product is observed to correlate with the production of an 8-mer RNase H cleavage product (Fig. 2D). The requirements for plus-strand transfer by E478Q RT were found to be similar to those defined for minus-strand transfer (7). In the case of the E478Q RT mutant, an 8-mer is never produced unless the enzyme is complemented with an exogenous RNase H. The reactions were performed under conditions such that the single RNase H cleavage product produced by E478Q RT would not be released due to its Tm of 60°C. In the avian system, it has been shown that tRNA is removed as an intact species (27). The primer utilized by the avian system is tRNATrp, which has a Tm of 56°C, only 4°C lower than the Tm of tRNA3Lys. This suggests that the avian RT may displace the primer once cleavage occurs. We have shifted the reaction temperatures to 42°C for both HIV-1 RT and E478Q RT, which yielded results identical to those of the 37°C reactions. This small shift in temperature was not sufficient to allow for release of the 17-mer (data not shown).

Nonviral RNase H’s were able to complement strand transfer, although this is not likely to occur in vivo. Chimeras have been constructed between AKR MuLV RT and E. coli RNase H to observe the effects of an RT possessing a greater RNase H-specific activity. The enzyme which was produced was functionally active in vitro (31); the enzyme possessed a much higher RNase H activity than the wild-type enzyme. Virion particles containing E. coli RNase H have also been examined. A chimeric enzyme utilizing M-MuLV Gag and E. coli RNase H I has been analyzed for its effects in vivo. The presence of the E. coli RNase H, rather than assisting replication, produces an antiviral effect reducing viral titers when utilized in a prophylaxis assay (42).

Manipulation of E478Q RT required the use of both magnesium and manganese divalent cations. DNA polymerization was optimal in the presence of Mg2+; manganese alone resulted in incomplete synthesis. For RNase H activity, Mn2+ was required, suggesting that manganese and magnesium occupy different active sites within the mutant enzyme. Mn2+ is capable of alternative coordination, which stabilizes specific conformations of the active site. These can be supported by alternative interactions in the metal binding site of E. coli RNase H. Studies have been performed in which the metal binding sites of E. coli RNase H have been replaced with ionic-charge interactions between Asp 10/Arg and Glu 48/Arg, producing a metal-independent enzyme (6). This enzyme possesses activity similar or comparable to that of the wild type.

Catalysis of plus-strand transfer by HIV-1 RT with the authentic tRNA3Lys was similar to that obtained with an RNA oligonucleotide mimicking tRNA3Lys. Previous studies have shown that in vivo DNA synthesis stops at the first Am within the authentic tRNA (25, 35). However, analysis of strand transfer in vitro with methylated and unmethylated tRNA3Lys indicates that Am at position 19 is not the sole determinant of termination of synthesis (4). Current research suggests that there are interactions of viral RNA and the A-rich loop of tRNA3Lys during initiation (18). Alternative structural components may play a role in the termination of plus-strand synthesis.

In reactions utilizing HIV-1 RT and E478Q RT, a predominant polymerase pause site was observed. Pausing has been previously characterized and shown to occur as a result of the template sequence and structure (20). Other studies have also shown that pause sites promote strand transfer (46). Along with pausing, strand transfer has been shown to produce mutations (29, 30, 46, 47). Studies analyzing internal strand transfer have been shown to possess great fidelity (8). In the current study, mutations and misincorporations were unable to be detected by the analysis utilized. However, pause sites were observed after approximately 14 nucleotides had been synthesized off the 26-mer primer. This was the case for HIV-1 RT as well as E478Q RT in the presence of Mn+2, Mg2+, or both. For the assays performed in this study, polymerization pauses are not substrates for strand transfer, since the acceptor molecule does not overlap in that region.

Strand transfer assays have been established in which the DNA primer is transferred between two DNA templates. These strand transfers are efficiently catalyzed by the E478Q RNase H mutant RT (13). These results imply an alternative mechanism to those involving RNA templates, where RNase H activity is required (7). Our studies indicate that the E478Q RT is capable of supporting plus-strand transfer; however, the RNase H activity must be supplied by an exogenous enzyme. RNase H-minus MuLV RT can displace short RNA oligonucleotides during DNA synthesis, but the presence of the RNase H domain increases the rate of synthesis on these templates (13, 19, 45).

HIV-1 RT is capable of supporting plus-strand transfer under the in vitro-reaction conditions defined here. Studies analyzing various strand transfer reactions have indicated that nucleocapsid protein (NC) enhanced strand transfer (1, 3, 8, 15, 34). Our plus-strand transfer reactions with the model RNA substrates were also performed in the presence and absence of nucleocapsid, and an increase in strand transfer was not observed with the addition of NC (data not shown). This may reflect a variation in NC preparations. In the in vitro system utilized here, the model viral genomes may not be long enough to support these interactions. In the virus, NC may be necessary to disrupt the interactions of the loops of the tRNA with the viral genome (17).

Our studies are consistent with other studies indicating a vital role for RNase H activity in the strand transfer process. More interesting is the defect which results from the mutation of glutamate 478 to glutamine. Perhaps utilizing this mutant with tRNAs which possess a lower Tm would result in efficient strand transfer without the need for exogenous RNase H enzymes to be present. Complementation of this mutant with E. coli RNase H allows strand transfer to be supported quite efficiently, indicating a requirement for either further degradation of the RNA primer or possibly a different mode of RNA cleavage which is defective in E478Q RT. The development of this assay system allows for further analysis of these questions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jeffrey Culp and Christine Debouch for the gift of recombinant HIV-1 RT. We also thank Stuart F. Le Grice for the gift of recombinant E478Q RT.

This work was supported by grant RO1-GM51151 from the NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allain B, Lapadat-Tapolsky M, Berlioz C, Darlix J L. Transactivation of the minus-strand DNA transfer by nucleocapsid protein during reverse transcription of the retroviral genome. EMBO J. 1994;13:973–981. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold E, Jacobo-Molina A, Nanni R G, Williams R L, Lu X, Ding J, Arthur J, Clark D, Zhang A, Ferris A L, Clark P, Hizi A, Hughes S H. Structure of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase/DNA complex at 7 Å resolution showing active site locations. Nature. 1992;357:85–89. doi: 10.1038/357085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auxilien S, Keith G, Le Grice S F, Darlix J L. Role of post-transcriptional modifications of primer tRNALys,3 in the fidelity and efficacy of plus strand DNA transfer during HIV-1 reverse transcription. J Biol Chem. 1999;27:44412–44420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Artzi H, Shemesh J, Zeelon E, Amit B, Kleiman L, Gorecki M, Panet A. Molecular analysis of the second template switch during reverse transcription of the HIV RNA template. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10549–10557. doi: 10.1021/bi960439x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cameron C E, Ghosh M A, LeGrice S F J, Benkovic S J. Mutations in HIV reverse transcriptase which alter RNase H activity and decrease strand transfer efficiency are suppressed by HIV nucleocapsid protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6700–6705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casareno R L B, Li D, Cowan J A. Rational redesign of a metal-dependent nuclease. Engineering the active site of magnesium-dependent ribonuclease H to form an active “metal-independent” enzyme. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:11011–11012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cirino N M, Cameron C E, Smith J S, Rausch J W, Roth M J, Benkovic S J, Le Grice S F J. Divalent cation modulation of ribonuclease functions of human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase. Biochemistry. 1995;4:9936–9943. doi: 10.1021/bi00031a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeStefano J, Ghosh J, Prasad B, Raja A. High fidelity of internal strand transfer catalyzed by human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1483–1489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeStefano J J, Mallaber L M, Rodriguez-Rodriguez L, Fay P J. Requirements for strand transfer between internal regions of heteropolymer templates by human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase. J Virol. 1992;66:6370–6378. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6370-6378.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeStefano J J, Wu W, Seehra J, McCoy J, Laston D, Albone E, Fay P J, Bambara R A. Characterization of an RNase H defective mutant of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 reverse transcriptase having an aspartate to asparagine change at position 498. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1994;1219:380–388. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudding L R, Nkabinde N C, Mizrahi V. Analysis of the RNA- and DNA-dependent DNA polymerase activities of point mutants of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase lacking ribonuclease H activity. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10498–10506. doi: 10.1021/bi00107a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan N, Rank K B, Slade D E, Poppe S M, Evans D B, Kopta L A, Olmsted R A, Thomas R C, Tarpley W G, Sharma S K. A drug resistance mutation in the inhibitor binding pocket of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase impairs DNA synthesis and RNA degradation. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9737–9745. doi: 10.1021/bi9600308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuentes G M, Palaniappan C, Fay P J, Bambara R A. Strand displacement synthesis in the central polypurine tract region of HIV-1 promotes DNA to DNA strand transfer. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29605–29611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao H-Q, Boyer P L, Arnold E, Hughes S H. Effects of mutations in the polymerase domain on the polymerase, RNase H, and strand transfer activities of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:559–572. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo J, Henderson L E, Bess J, Kane B, Levin J G. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein promotes efficient strand transfer and specific viral DNA synthesis by inhibiting TAR-dependent self-priming from minus-strand strong stop DNA. J Virol. 1997;71:5178–5188. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5178-5188.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobo-Molina A, Arthur J, Clark D, Williams R L, Nanni R G, Clark P, Ferris A L, Hughes S H, Arnold E. Crystals of a ternary complex of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase with a monoclonal antibody Fab fragment and double-stranded DNA diffract x-rays to 3.5-A resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10895–10899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang S, Zhang Z, Morrow C D. Identification of a sequence within U5 required for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to stably maintain a primer binding site complementary to tRNAMet. J Virol. 1997;71:207–217. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.207-217.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang S M, Wakefield J K, Morrow C D. Mutations in both the U5 region and the primer-binding site influence the selection of the tRNA used for the initiation of HIV-1 reverse transcription. Virology. 1996;222:401–404. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelleher C D, Champoux J J. Characterization of RNA strand displacement synthesis by Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9976–9986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klarmann G J, Schauber C A, Preston B D. Template-directed pausing of DNA synthesis by HIV-1 reverse transcriptase during polymerization of HIV-1 sequences in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9793–9802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohlstaedt L A, Steitz T A. Reverse transcriptase of human immunodeficiency virus can use either tRNA(Lys,3) or Escherichia coli tRNA (Gln,2) as a primer in an in vitro utilization assay. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9652–9656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohlstaedt L A, Wang J, Friedman J M, Rice P A, Steitz T A. Crystal structure at 3.5 A resolution of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase complexed with an inhibitor. Science. 1992;256:1783–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.1377403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LeGrice S F J, Gruninger-Leitch F. Rapid purification of homodimer and heterodimer HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by metal chelate affinity chromatography. Eur J Biol. 1990;187:307. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leis J, Aiyar A, Cobrinik D. Regulation of initiation of reverse transcription of retroviruses. In: Skalka A M, Goff S P, editors. Reverse transcriptase. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1993. pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller M D, Farnet C M, Bushman F D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes: studies of organization and composition. J Virol. 1997;71:5382–5390. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5382-5390.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore M, Sharp P. Site-specific modification of pre-mRNA: the 2′-hydroxyl groups at the splice sites. Science. 1992;256:992–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1589782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omer C A, Faras A J. Mechanism of release of the avian retrovirus tRNA Trp primer molecule from viral DNA by ribonuclease H during reverse transcription. Cell. 1982;30:797–805. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oude-Essink B B, Das A T, Berkhout B. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase discriminates against non-self tRNA primers. J Mol Biol. 1996;264:243–254. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peliska J A, Balasubramanian S, Giedroc D P, Benkovic S J. Recombinant HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein accelerates HIV-1 reverse transcriptase catalyzed DNA strand transfer reactions and modulates RNase H activity. Biochemistry. 1994;33:13817–13823. doi: 10.1021/bi00250a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peliska J A, Benkovic S J. Mechanism of DNA strand transfer reactions catalyzed by HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Science. 1992;258:1112–1118. doi: 10.1126/science.1279806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Post K, Guo J, Kalman E, Uchida T, Crouch R J, Levin J G. A large deletion in the connection subdomain of murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase or replacement of the RNase H domain with Escherichia coli RNase H results in altered polymerase and RNase H activities. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5508–5517. doi: 10.1021/bi00072a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Powell M D, Ghosh M, Jacques P S, Howard K J, Le Grice S F, Levin J G. Alanine-scanning mutations in the “primer grip” of p66 HIV-1 reverse transcriptase result in selective loss of RNA priming activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13262–13269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pullen K A, Ishimoto L K, Champoux J J. Incomplete removal of the RNA primer for minus-strand DNA synthesis by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. J Virol. 1992;66:367–373. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.367-373.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodriguez-Rodriguez L, Tsuchihashi Z, Fuentes G M, Bambara R A, Fay P J. Influence of human immunodeficiency virus nucleocapsid protein on synthesis and strand transfer by reverse transcriptase in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15005–15011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roth M J, Schwartzberg P, Goff S P. Structure of the termini of DNA intermediates in the integration of retroviral DNA: dependence of IN function and terminal DNA sequence. Cell. 1989;58:47–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roth M J, Tanese N, Goff S P. Purification and characterization of murine retroviral reverse transcriptase expressed in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:9326–9335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schatz O, Cromme F V, Gruninger-Leitch F, LeGrice S F J. Point mutations in conserved amino acid residues within the C-terminal domain of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase specifically repress RNase H function. FEBS Lett. 1989;237:311–314. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81559-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith C M, Potts III W B, Smith J S, Roth M J. RNase H cleavage of tRNAPro mediated by M-MuLV and HIV-1 reverse transcriptases. Virology. 1997;229:437–446. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith C M, Leon O, Smith J S, Roth M J. Sequence requirements for removal of tRNA by an isolated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNase H domain. J Virol. 1998;72:6805–6812. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6805-6812.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith J S, Roth M J. Purification and characterization of an active human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNase H domain. J Virol. 1993;67:4037–4049. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4037-4049.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith J S, Roth M J. Specificity of human immunodeficiency virus-1 reverse transcriptase-associated ribonuclease H in removal of the minus-strand primer, tRNALys3. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15071–15079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.VanBrocklin M, Ferris A L, Hughes S H, Federspiel M J. Expression of a murine leukemia virus Gag-Escherichia coli RNase HI fusion polyprotein significantly inhibits viral spread. J Virol. 1997;71:3312–3318. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3312-3318.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wakefield J K, Morrow C D. Mutations within the primer binding site of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 define sequence requirements essential for reverse transcription. Virology. 1996;220:290–298. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wakefield J K, Rhim H, Morrow C D. Minimal sequence requirements of a functional human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primer binding site. J Virol. 1994;68:1605–1614. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1605-1614.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whiting S H, Champoux J J. Properties of strand displacement synthesis by Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase: mechanistic implications. J Mol Biol. 1998;278:559–577. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu W, Blumberg B M, Fay P J, Bambara R A. Strand transfer mediated by human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase in vitro is promoted by pausing and results in misincorporations. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:325–332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu W, Palaniappan C, Bambara R A, Fay P J. Differences in mutagenesis during minus strand, plus strand and strand transfer (recombination) synthesis of the HIV-1 gene in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;9:1710–1718. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.9.1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Z, Kang S M, LeBlanc A, Hajduk S L, Morrow C D. Nucleotide sequences within the U5 region of the viral RNA genome are the major determinants for a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to maintain a primer binding site complementary to tRNA(His) Virology. 1996;226:306–317. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]