Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a betaherpesvirus, is a pathogen which escapes immune recognition through various mechanisms. In this paper, we show that HCMV down regulates gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-induced HLA-DR expression in U373 MG astrocytoma cells due to a defect downstream of STAT1 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation. Repression of class II transactivator (CIITA) mRNA expression is detected within the first hours of IFN-γ–HCMV coincubation and results in the absence of HLA-DR synthesis. This defect leads to the absence of presentation of the major immediate-early protein IE1 to specific CD4+ T-cell clones when U373 MG cells, used as antigen-presenting cells, are treated with IFN-γ plus HCMV. However, presentation of endogenously synthesized IE1 can be restored when U373 MG cells are transfected with CIITA prior to infection with HCMV. Altogether, the data indicate that the defect induced by HCMV resides in the activation of the IFN-γ-responsive promoter of CIITA. This is the first demonstration of a viral inhibition of CIITA expression.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a betaherpesvirus, is pathogenic almost exclusively in immunocompromised individuals. Cellular immune response is thought to control HCMV in immunocompetent people, both in the acute phase and in the latent infection which ensues (for a review, see reference 6). Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells contribute greatly to immunological control, as revealed by the presence of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in patients who recover from acute infections (37) and by the prevention of HCMV disease following the injection of viral matrix-specific CD8+ clones to bone marrow transplant patients (44). CD4+ T cells against HCMV proteins have also been described (4, 12, 28), and a significant response towards IE1, the major immediate-early DNA-binding protein, has been reported (3, 9). The precursor frequencies of IE1-specific CD4+ T cells are high in latently infected individuals (9), and cytokines such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) found in the supernatant of CD4+ T-cell clones specific for IE1 significantly reduce HCMV replication (10). The role of CD4+ T cells in HCMV infections was inferred from these in vitro studies and from in vivo studies showing that CD4+ T cells are required for the clearance of mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) in salivary glands of mice (22).

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II expression is a key element in the control of the immune response. It is required for the activation of T lymphocytes in the process of antigen (Ag) presentation by professional or nonprofessional antigen-presenting cells (APC) (13). Three essential transactivators of MHC class II genes have been identified: RFX5 and RFX-AP are part of the RFX complex that binds to the X box of all MHC class II promoters, while the class II transactivator (CIITA) is itself tightly regulated, and this transactivator functions as the master controller of MHC class II expression, probably in all physiological conditions (30, 42).

Both constitutive and inducible expressions of MHC class II genes are indeed dependent on CIITA, and the CIITA gene is itself controlled by distinct alternative promoters (33). While CIITA promoters I and III are specific for constitutive expression in dendritic cells and B lymphocytes, respectively, induction of CIITA, and hence of MHC class II, by IFN-γ is mediated by promoter IV. Activation by IFN-γ takes place via a cascade of events which involves tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1 by JAK1 and JAK2 kinases, followed by nuclear translocation and binding of STAT1 to a GAS sequence within the promoter of the target gene (reviewed in reference 8). In the case of the activation of CIITA promoter IV by IFN-γ, cooperation between three distinct and essential transacting factors, STAT1 and USF-1 (binding cooperatively to a GAS-E box motif) and IRF-1, has recently been described in detail (34). This also explains why JAK1 and STAT1 mutants lack inducibility of MHC class II by IFN-γ (31). The detailed dissection of these multiple steps of the cascade, from IFN-γ activation to expression of MHC class II molecules (33, 34), now allows the assignment of various types of inhibition to specific steps within this cascade.

APC capacity is triggered by IFN-γ treatment in many cell types, due to the induction of expression of HLA class II, the invariant chain, and HLA-DM which catalyzes the release of invariant chain-derived Clip peptide from HLA class II molecules and allows the binding of processed peptides (36). MHC class II molecules are known to present peptides derived from extracellular, exogenous Ag to CD4+ T cells (36). However, it appears that presentation of intracellular endogenous, especially viral, Ags is common (14, 23). This suggests cognate interaction between CD4+ T cell and the infected MHC class II-positive APC.

Immunological controls of cytomegaloviruses are counterbalanced by escape mechanisms from class I-mediated recognition by CD8+ T cells, as recently described (46). Several genes localized in the unique short (US) region of the HCMV genome are responsible for down regulating HLA class I expression at multiple levels through retrotranslocation of HLA class I heavy chain to the cytosol (US2 [19, 47] and US11 [21, 45]), retention in the endoplasmic reticulum (US3 [1, 20]) and inhibition of TAP translocation of peptides (US6 [2, 17, 26]). The CD4+ compartment of cellular immunity has been suspected to be down regulated since the observation by Sedmak et al. (38) that HCMV inhibits HLA class II expression induced by IFN-γ. A recent report by Miller et al. (32) has described a mechanism of JAK1 proteolysis by HCMV to explain the inhibition of IFN-γ-mediated induction of HLA class II. In mice, Heise et al. (15) have reported that MCMV down regulates IFN-γ-induced expression of MHC class II-related molecules through the inhibition of their transcription. The mechanism, which occurs downstream of STAT1 activation, has yet to be determined.

In this paper, we made use of an astrocytoma cell line, U373 MG, which is fully permissive to HCMV. This cell line can also be induced to express HLA-DR by treatment with IFN-γ and to subsequently present Ag to HCMV IE1-specific CD4+ T cells (11). We show here that HCMV infection prevents induction of HLA-DR expression by IFN-γ in U373 MG cells. This inhibition occurs downstream of the activation of STAT1, whose phosphorylation and nuclear translocation are not inhibited by HCMV. CIITA transcription is strongly repressed by cotreatment of cells with IFN-γ plus HCMV. Logically, this strong reduction of MHC class II expression by HCMV results in the absence of IE1 presentation and recognition by CD4+ T-cell clones. Transfection of the U373 MG cells by CIITA, however, can restore both HLA-DR expression and the ability to present endogenously produced IE1 to CD4+ T cells, even following HCMV infection. These results indicate that, in IFN-γ-treated cells, down regulation of MHC class II expression by HCMV results from a repression of CIITA induction. The modulation of MHC class II-dependent IE1 recognition by viral infection, via an effect on CIITA expression, can thus allow HCMV-infected cells to escape from the CD4+ T-cell response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus, cell lines, and the IE1-specific CD4+ T-cell clone.

HCMV (Towne strain) stocks were obtained by infection of foreskin fibroblasts at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 in 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) culture medium (RPMI-Glutamax I supplemented with sodium pyruvate and antibiotics from GIBCO-BRL). U373 MG cells were cultured in 10% FCS culture medium. HCMV, fibroblasts, and U373 MG cells were kind gifts from S. Michelson (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France).

Transfection of U373 MG cells with the pSRα-neo/CIITA-Tag plasmid was performed by using the calcium phosphate method. Transfected cells were then cloned by limiting dilution and HLA-DR expression was controlled by flow cytometry.

The previously described CD4+ T-cell clone FzD3 specific for IE1 was obtained by limiting dilution from a healthy HCMV-seropositive donor (10). FzD3 clone was maintained by weekly restimulations with phytohemagglutinin and allogeneic irradiated peripheral blood mononuclear cells in the presence of interleukin 2 (IL-2) (20 U/ml) in culture medium supplemented with 10% human serum.

HCMV inoculum was inactivated by using alternating UV and gamma irradiation. Both were used to ensure that the results did not depend on the inactivation method.

MAb.

E13, an immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb) specific for immediate-early proteins UL122 to -123, was a kind gift from M.-C. Mazeron (Hôpital Lariboisière, Paris, France). MAb CCH2 (anti-UL44 early protein) was purchased from DAKO. Control IgG1 myeloma protein was from Sigma. W6/32, OKT3, and L243 MAbs were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. DA6-231, an anti-HLA-DR β chain (43), was a kind gift from S. Demotz (University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland).

RNase protection assays.

Quantitative analysis of CIITA and GBP mRNAs was performed by RNase protection assays as described in detail elsewhere (30).

Immunoprecipitation.

U373 MG (106 cells) was plated in culture medium in 25-cm2 flasks and was either left untreated or was treated with IFN-γ (300 U/ml), with IFN-γ (300 U/ml) plus HCMV (MOI = 5), or incubated with HCMV alone (MOI = 5).

For MHC class I immunoprecipitation, cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 24 h later, incubated in methionine-and-cysteine-free medium (Gibco) for 1 h, and labelled with [35S]methionine plus [35S]cysteine (100 μCi/ml) (ICN) for 2 h. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.05 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 50 mM Tris [pH 7.6]) for 45 min on ice. Preclearing of the lysate was performed overnight by using protein A-conjugated Sepharose beads (Pharmacia). W6/32 antibody was then added to the lysate for 1.5 h at 4°C. Protein A-coupled Sepharose beads were then added, and incubation was continued for an additional 2 h at 4°C.

For MHC class II immunoprecipitation, cells were washed in PBS 18 h after treatment, incubated for 1 h in methionine-and-cysteine-free medium and labelled with [35S]methionine plus [35S]cysteine for the last 6 h. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.05 mM PMSF, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.6]) for 45 min on ice. Preclearings were performed as follows: the cell lysates were incubated with normal mouse serum and protein G-conjugated Sepharose beads for 2 h. A second preclearing was performed by using 50 μl of zysorbin (Zymed) for 4 h. DA6-231 antibody was then added to the cell lysates, and incubation was performed overnight at 4°C. Protein G-conjugated Sepharose beads were then added, and incubation was maintained for another 2 h. For both MHC class I and class II immunoprecipitations, the beads were then washed and boiled in 5% β-mercaptoethanol reducing Laemmli buffer and run on 10% polyacrylamide gels. Gels were fixed, incubated in Amplify (Amersham), vacuum dried, and exposed to hyperfilm-MP (Amersham).

Flow cytometry.

U373 MG cells were infected by using supernatant from infected fibroblasts. U373 MG cells were treated with IFN-γ (300 U/ml) or with IFN-γ plus HCMV or IFN-γ plus gamma-irradiated HCMV. The contents of wells were aspirated and replaced with fresh medium and fresh IFN-γ on day 3. The culture was allowed to proceed for an additional 3 days. U373 MG cells were then double stained for cell surface HLA-DR and intracellular immediate-early (UL122 to -123) or early (UL44) proteins and analyzed by flow cytometry. Cell viability was assessed by using Trypan Blue exclusion and was found to be greater than 80%.

For double staining, U373 MG cells were incubated for 20 min at 4°C with saturating amounts of OKT3 (used as a control) or L243 MAb in Ca2+/Mg2+-free PBS–3% FCS plus 0.1% NaN3 (staining buffer), washed twice in staining buffer, then incubated with goat F(ab′)2 fragment anti-mouse IgG coupled to fluorescein isothiocyanate (Sigma). Cells were washed twice in staining buffer, then incubated for 90 min at 4°C with OKT3 to saturate unbound anti-mouse IgG-fluorescein isothiocyanate Fab sites, then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at 4°C and washed with PSN buffer (PBS + 1% normal goat serum + 1 mM EDTA + 0.05% saponin). MAbs (IgG1) specific for HCMV immediate-early (E13) and early (CCH2) proteins, or IgG1 myeloma protein (Sigma) used as a control, were diluted in PSN, and added to cell samples for a 90-min incubation at 37°C. Cells were washed twice in PSN buffer and incubated for 20 min at 4°C with isotype-specific phycoerythrin-coupled anti-IgG1 goat anti-mouse F(ab′)2 antiserum (Southern Biotechnology). Samples were then analyzed by using an EPICS Elite cell sorter.

Immunocytochemistry.

U373 MG cells were seeded at 30,000 cells per well (24-well plate; FALCON) in RPMI 1640 supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% FCS and were cultured for 24 h. They were then cultured in serum-free medium for another 24 h. Then they were treated with IFN-γ (300 U/ml) and, except for controls, were infected with HCMV for 15 or 30 min or 1, 6, or 24 h.

Cells were washed once with 1× PBS and were fixed with 1 ml of 1× PBS containing 3% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 4°C. Immunochemistry was then performed by using a rabbit PhosphoPlus STAT1 (Tyr 701) antiserum (Biolabs). The biotinylated secondary antibody was a peroxidase-coupled horse anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG (Vectastain ABC kit; Vector Laboratories). Staining was revealed by using diaminobenzidine (Sigma) and H2O2.

IE1-specific CD4+ T-cell clone response.

U373 MG cells were seeded at 1.5 × 105 cells/well in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS in a 6-well plate (FALCON). Cells were mock infected or treated with HCMV or UV-irradiated HCMV (MOI = 5) and treated simultaneously with IFN-γ (300 U/ml). Cells were fed on day 3 with fresh medium supplemented with IFN-γ (300 U/ml) and were left in culture for an additional 2 days.

U373 MG-CIITA cells were mock infected or infected with either HCMV or UV-irradiated HCMV at an MOI of 5 for 5 days. U373 MG and U373 MG-CIITA cells were incubated with specific IE1 peptide (amino acids 91 to 110) (Neosystem, Strasbourg, France) at a concentration of 10 μM overnight.

U373 MG and U373 MG-CIITA cells were then harvested, washed, and plated in triplicate (3 × 104 cells per well) in a 96-well plate in the presence of 3 × 104 FzD3 IE1-specific CD4+ T-cell clones in a final volume of 200 μl for 24 h. Then supernatants were collected, triplicates were pooled, and IFN-γ was measured by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Medgenix Screening Line).

Western blotting.

U373 MG cells (106 in T25 culture flasks) were incubated in culture medium alone or in the presence of IFN-γ (300 U/ml) or IFN-γ (300 U/ml) plus HCMV (MOI = 5) for different time points in 10% FCS culture medium.

In another protocol derived from reference 32, cells were left untreated, treated with IFN-γ alone, or treated with IFN-γ after 72 h of infection by HCMV.

The incubation was stopped by using ice-cold PBS. Cells were washed, detached with a cell scraper in PBS, and pelleted at 300 × g for 10 min. Cells were lysed in reducing Laemmli buffer. Samples equivalent to 3 × 105 cells each were run on a 7.5% acrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham). Membranes were incubated with a rabbit PhosphoPlus STAT1 (Tyr 701)-specific antiserum (Biolabs), followed by incubation with a secondary peroxidase-coupled anti-rabbit antiserum (Biolabs). Bands were revealed by using an ECL detection kit (Amersham).

RESULTS

Inhibition of IFN-γ-induced HLA-DR expression by HCMV infection.

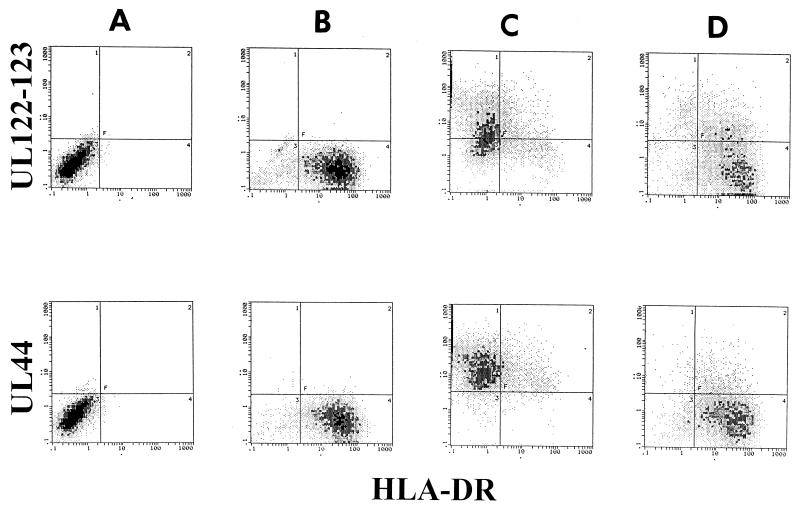

We tested the induction of HLA-DR by IFN-γ in infected U373 MG cells (Fig. 1). As expected and as previously shown (11), IFN-γ in the absence of HCMV induced high levels of HLA-DR expression in U373 MG cells. Simultaneous coincubation of HCMV with IFN-γ almost totally prevented HLA-DR expression. A small proportion (12%) of cells expressed low levels of HLA-DR molecules in spite of HCMV infection. This incomplete down regulation of HLA-DR by HCMV was observed in all the experiments performed. In these samples, immediate-early (UL122 and UL123) and early (UL44) proteins were detectable by using E13 and CCH2 MAbs, respectively. This indicated that, when U373 MG cells are incubated with IFN-γ and HCMV simultaneously, IFN-γ does not prevent HCMV infection, but HCMV inhibits IFN-γ-induced HLA-DR expression. To test whether active infection accounted for the inhibition of HLA-DR, HCMV was gamma irradiated (800 Gy) and tested in the same experiment. Twenty percent of the cells expressed residual immediate-early proteins, and only 8% expressed the protein encoded by UL44, recognized by CCH2 antibody. This clearly showed that the virus was inactivated. Irradiated HCMV inoculum did not prevent IFN-γ-induced HLA-DR expression. In addition, pelleted HCMV, but neither supernatant nor UV-irradiated HCMV, repressed HLA-DR induction (results not shown). This suggested that neither virion-associated proteins nor cytokines included in the inoculum were responsible for repression of HLA-DR induction.

FIG. 1.

Inhibition of IFN-γ-induced HLA-DR expression by HCMV. U373 MG cells were either untreated (column A), treated with IFN-γ (300 U/ml) (column B), treated with IFN-γ plus HCMV (column C), or treated with IFN-γ plus gamma-irradiated HCMV (column D), as indicated in Materials and Methods. U373 MG cells were then double stained for cell surface HLA-DR and intracellular IE (upper row) or E (lower row) proteins and analyzed by flow cytometry. Three experiments, which gave similar results, were performed.

Inhibition of IFN-γ-induced HLA-DR synthesis by HCMV infection.

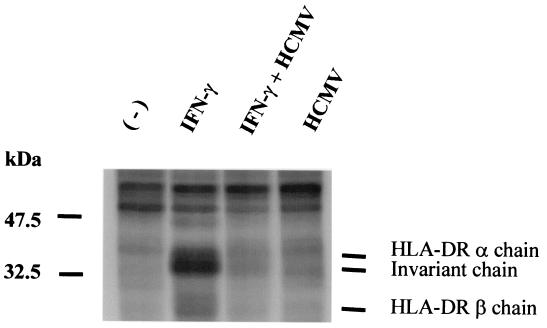

To test whether the inhibition of HLA-DR expression was observed at an earlier step than cell surface expression, we immunoprecipitated nascent HLA-DR molecules from [35S]Met-[35S]Cys-labelled U373 MG cells by using the β-chain-specific MAb DA6-231. As shown in Fig. 2, a 24-h treatment with IFN-γ induced the appearance of bands which correspond to the HLA-DR α, the invariant, and the HLA-DR β chains, respectively. The β chain, which contains fewer Met and Cys residues than the α and invariant chains, was less labelled, and the corresponding band was fainter. In IFN-γ plus HCMV-infected cells, these bands were no longer detected. This result confirms HCMV inhibition of HLA-DR expression in U373 MG cells and shows that this inhibition is detectable at the level of protein synthesis after a 24-h cotreatment with IFN-γ plus HCMV.

FIG. 2.

Inhibition of IFN-γ-induced HLA-DR β chain synthesis by HCMV. U373 MG cells were treated with IFN-γ and/or HCMV or left untreated for 18 h and were pulsed with 35S for 6 h. Cells were lysed, and HLA-DR β chain synthesis was analyzed by immunoprecipitation by using DA6-231 antibody coupled to Sepharose-protein G. Three experiments, which gave similar results, were performed.

MHC class I up regulation by IFN-γ is not repressed by HCMV.

To test whether HCMV also inhibited IFN-γ-induced MHC class I upregulation, we performed immunoprecipitations of HLA-A, -B, and -C molecules by using W6/32 MAb. As shown in Fig. 3, and as expected, MHC class I protein expression was upregulated by IFN-γ. This up regulation was not inhibited by HCMV concomitant infection. As previously described (19), HLA class I expression was decreased in U373 MG cells infected with HCMV. The lack of effect of HCMV infection on the increase of MHC class I expression induced by IFN-γ indicates a clear dissociation between the effects of HCMV on the MHC class II and MHC class I pathways of activation by IFN-γ.

FIG. 3.

Increase of synthesis of HLA class I proteins by IFN-γ in HCMV-treated U373 MG cells. U373 MG cells were treated with IFN-γ and/or HCMV or left untreated for 24 h and pulsed with [35S]methionine for 2 h. Cells were lysed, and HLA class I synthesis was measured by immunoprecipitation by using W6/32 antibody coupled to Sepharose-protein A. Two experiments, which gave similar results, were performed.

Inhibition of HLA-DR synthesis is not due to a defect in IFN-γ-induced STAT1 activation.

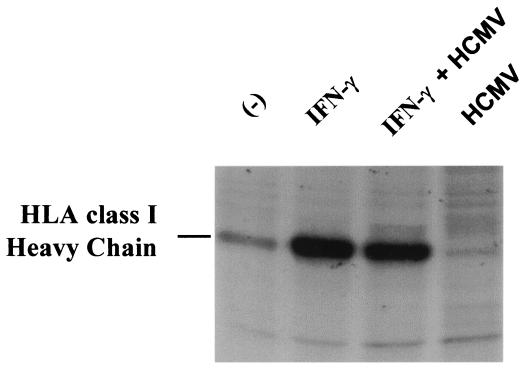

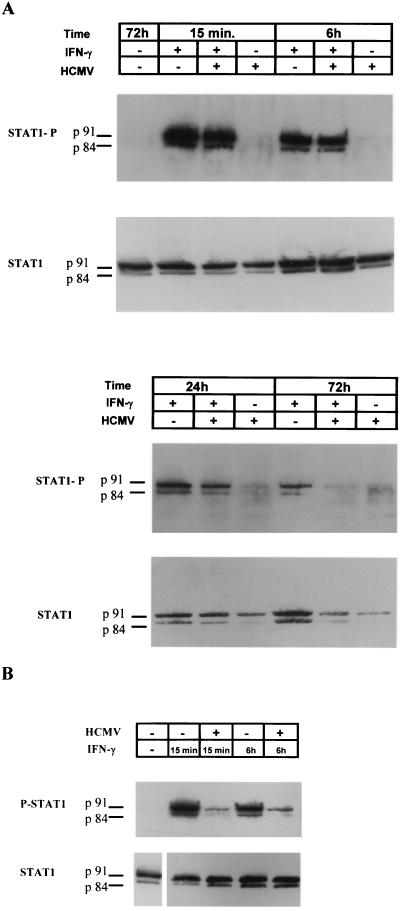

Since IFN-γ-induced HLA-DR expression is dependent upon STAT1 activation (24), we tested whether STAT1 phosphorylation, which occurs rapidly in response to IFN-γ, was inhibited by HCMV. As shown in Fig. 4A, and in accordance with previous reports (39, 41), STAT1 was phosphorylated after as little as 15 min of IFN-γ treatment. Both p91 and splice variant p84 were detected. This phosphorylation was present at late time points (24 and 72 h) and was not inhibited by HCMV infection at a time point (24 h) when HLA-DR proteins were not detectable (see Fig. 2). These results suggested that inhibition of HLA-DR expression was not related to defects in STAT1 phosphorylation in our experimental conditions. However, STAT1 phosphorylation was inhibited after a 72-h coincubation with IFN-γ plus HCMV. Similar results were observed when we used foreskin fibroblasts (data not shown). Recently, Miller et al. (32) have described an inhibition of IFN-γ-induced HLA-DR expression by HCMV in endothelial cells and fibroblasts through JAK1 proteolysis, which logically leads to reduced STAT1 phosphorylation. These observations were made by using a different protocol, consisting of a 72-h preincubation with HCMV before IFN-γ treatment. Using their protocol, we also observed that STAT1 phosphorylation was inhibited after 15 min and 6 h of IFN-γ treatment in U373 MG-infected cells (Fig. 4B). This shows that U373 MG cells were not refractory to the mechanism described by Miller et al., and our data suggest the existence of another mechanism, perhaps earlier in the infection, which does not involve the inhibition of STAT1 phosphorylation.

FIG. 4.

STAT1 activation in the presence of IFN-γ and HCMV. (A) U373 MG cells were either untreated or incubated in the presence of IFN-γ or IFN-γ plus HCMV for 15 min and 6, 24, and 72 h. STAT1 phosphorylation was evaluated in a Western blot by using an anti-P-Tyr-STAT1 specific antiserum. Levels of STAT1 protein were evaluated in the same samples by using an anti-STAT1 antiserum. (B) U373 MG cells were either incubated with IFN-γ for 15 min or 6 h in the absence of HCMV or incubated with IFN-γ after 72 h of infection with HCMV. STAT1 phosphorylation was then evaluated in a Western blot by using an anti-P-Tyr-STAT1 specific antiserum. Levels of STAT1 protein were evaluated in the same samples by using an anti-STAT1 antiserum. Three experiments, which gave similar results, were performed.

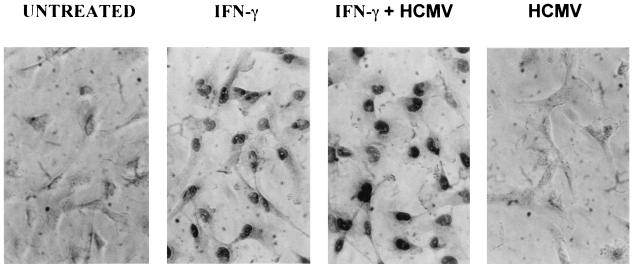

STAT1 is quickly translocated to the nucleus after phosphorylation (8). In U373 MG cells, nuclear translocation of STAT1 occurred after 15 min of incubation with IFN-γ (not shown). Figure 5 shows that IFN-γ-induced P-STAT1 translocation to the nucleus was not inhibited by HCMV infection even after a 24-h coincubation. Therefore, STAT1 activation and nuclear translocation occur with the same intensity and same kinetics in IFN-γ- and IFN-γ plus HCMV-treated U373 MG cells at experimental time points when HCMV inhibits IFN-γ-induced HLA-DR expression.

FIG. 5.

Nuclear translocation of P-STAT1. U373 MG cells either were left untreated or were incubated with IFN-γ, HCMV, or IFN-γ plus HCMV for 24 h. Nuclear localization of P-STAT1 was evaluated by immunohistochemistry by using an anti-P-STAT1 specific antiserum. Two experiments, which gave similar results, were performed.

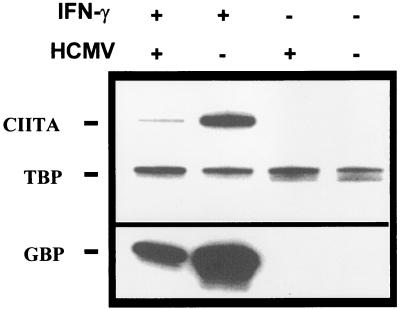

Repression of CIITA mRNA expression by HCMV infection.

Since HLA-DR repression was not mediated by a defect in STAT1 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, we looked for an inhibition further down the pathway of IFN-γ signalling. We therefore looked at CIITA transcription in IFN-γ- and IFN-γ plus HCMV-treated U373 MG cells. RNase protection assays (Fig. 6) showed that CIITA mRNA expression was induced after 6 h of treatment with IFN-γ, as previously described (7, 41). The levels of CIITA mRNA were 13.5 times lower in cells treated with IFN-γ plus HCMV than in cells treated with IFN-γ alone. Interestingly, expression of the GBP gene, which is also up-regulated by IFN-γ, was also inhibited by HCMV (ninefold decrease), implying a mechanism common to the regulation of these two genes. The kinetics of induction of CIITA by IFN-γ and its inhibition in HCMV-infected cells suggest that the quick repression of CIITA after infection accounts for the observed reduction in HLA-DR expression by HCMV. In an additional experiment, CIITA transcription was found to be still repressed after 24 h of treatment with IFN-γ plus HCMV (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Inhibition of IFN-γ-induced CIITA transcription by HCMV. U373 MG cells were incubated for 6 h with IFN-γ, HCMV, IFN-γ plus HCMV, or were left untreated in culture medium. Quantitative expression of CIITA and GBP mRNA was examined by RNase protection assay. A TBP probe was used as an internal control. Two experiments, which gave similar results, were performed.

Restoration of CD4+ T-cell clone recognition of HCMV IE1 by constitutive CIITA expression in infected U373 MG cells.

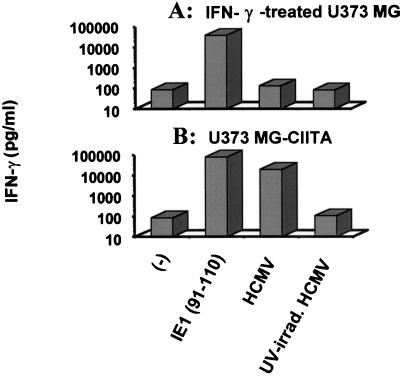

We next tested the consequences of HLA-DR repression on the activation of a specific anti-IE1 T-cell clone which recognizes the HCMV IE1 peptide (amino acids 91 to 110) presented by HLA-DR3-typed U373 MG (11). Figure 7 shows IFN-γ production as an assay for activation of T-cell clone FzD11. This clone produced high amounts of IFN-γ when incubated with IFN-γ-treated U373 MG cells pulsed with the IE1 peptide (amino acids 91 to 110) (Fig. 7A). However, the FzD11 CD4+ T-cell clone was not activated by U373 MG cells infected by HCMV and treated with IFN-γ for 5 days. This was not due to the inhibition of IE1 production since high levels of immediate-early proteins were detectable in this protocol (Fig. 1).

FIG. 7.

Restoration of recognition of endogenous IE1 by specific CD4+ T-cell clone through constitutive expression of CIITA. Untransfected U373 MG cells were treated with IFN-γ and UV-inactivated or unmanipulated HCMV and were used as APC in T-cell specificity assays of IE1-specific CD4+ T-cell clones. Production of IFN-γ was measured (A). CIITA-transfected U373 MG cells were treated either with UV-irradiated or unmanipulated HCMV and used as APC in T-cell specificity assays of IE1-specific CD4+ T-cell clones (B). Three experiments, which gave similar results, were performed.

Figure 7B shows that the FzD11 clone was activated in the presence of CIITA-transfected U373 MG cells (U373 MG-CIITA cells) either incubated with the IE1 peptide (amino acids 91 to 110) or infected with HCMV in the absence of IFN-γ treatment. This clone was not activated when U373 MG-CIITA cells were treated with UV-irradiated virus (Fig. 7B). This suggested that endogenously produced IE1 was presented during HCMV infection. Difference of IFN-γ production by the clone when incubated with U373 MG-CIITA cells infected by HCMV or presenting IE1 peptide can be explained by the high concentration of peptide used (10 μM) which could not be reached during infection. Similar results were obtained with other anti-IE1 CD4+ T-cell clones (results not shown).

Therefore, our results show the following: (i) the repression of HLA-DR expression in IFN-γ-treated U373 MG cells affects the anti-IE1 CD4+ T-cell response by preventing the presentation of endogenous IE1 peptide; and (ii) constitutive expression of CIITA restores IE1 presentation by infected U373 MG cells, indicating that the defect of HLA-DR expression due to HCMV occurs upstream of the expression of CIITA.

DISCUSSION

We have shown in this paper that HCMV escapes from CD4+ T-lymphocyte recognition through inhibition of IFN-γ-induced HLA-DR expression. The inhibition is mediated by negative regulation of CIITA transcription. This is the first report of virus-mediated inhibition of CIITA transcription.

A defect linked with viral infection is clearly involved in the repression of HLA-DR expression. This was concluded from the need for infectious virus to inhibit HLA-DR induction and from the observation of viral protein expression in cells with repressed HLA-DR. The inhibition of HLA-DR is not due to cytokines contained in the viral inoculum for the following reasons: first, irradiated virus had no negative effect on IFN-γ-induced HLA-DR expression; second, pelleted infectious virus prevented HLA-DR induction effectively (data not shown); third, the amounts of transforming growth factor β1, which is known to be involved in HLA-DR down regulation through inhibition of CIITA transcription (25, 35), were found to be similar in the inoculum to that of regular 10% FCS culture medium (300 pg/ml) (data not shown), and IFN-β has been reported to act downstream of CIITA (29). Treatment of cells with phosphonacetic acid did not prevent HLA-DR inhibition (data not shown), which suggests that the viral protein involved is encoded in the immediate-early and early phases of infection. Besides, the kinetics of CIITA inhibition (6 h postinfection) suggest that the repression occurs in the immediate-early phase of infection. However, this point needs further investigation to help identify the viral protein(s) involved.

Our present data point to a transcriptional modulation of CIITA expression due to viral infection. Therefore, inhibition of the IFN-γ-inducible promoter IV is expected to account for the down regulation of CIITA. This inhibition is not unique to CIITA, since repression of both CIITA and GBP was observed. As both are under the control of IRF-1 (5, 34), which is itself activated by STAT1 (27), a defect in IRF-1 transcription or in its binding to the IRF-1 box of promoter IV may be suspected. However, the increase of HLA class I synthesis induced by IFN-γ, also under the control of IRF-1 (18), was not inhibited by HCMV, in accordance with a previous report (16). This indicates uncoupling of HLA class I and class II regulation in response to IFN-γ and HCMV and argues against a major role of IRF-1 in the inhibition of HLA-DR induction. Alternatively, functional activity of STAT1 through interaction with other transcriptional factors such as USF1 (34) may be impaired and result in down regulation of CIITA transcription.

Multistep inhibitions of IFN-γ-induced HLA class II expression and escape from CD4+ T-cell response in HCMV infection are likely to represent the counterpart of HLA class I inhibition of expression (46). A recent paper by Miller et al. (32) showed that degradation of the JAK1 protein was responsible for down regulation of HLA-DR in endothelial cells. Although this process was found to occur in the immediate-early or early phase of infection, it required infection of the cells prior to IFN-γ treatment to effectively inhibit HLA-DR induction. In the present paper, it is clear that the impaired HLA-DR production was not due to a defect in STAT1 activation. Therefore, our protocol of simultaneous coincubation of IFN-γ and HCMV unravels a new mechanism of HLA-DR inhibition which is not related to STAT1 activation, since STAT1 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation were present at a time point (24 h) when HLA-DR protein synthesis was repressed. Rather, this mechanism involves the inhibition of CIITA RNA expression. However, U373 MG was not refractory to the mechanism described by Miller et al., since we observed an inhibition of STAT1 phosphorylation when their protocol was applied (Fig. 4B), and when we used our protocol, STAT1 phosphorylation was strongly diminished after 72 h of cotreatment with IFN-γ plus HCMV. We conclude that several mechanisms can account for the diminished HLA-DR expression in response to IFN-γ. We suggest that CIITA repression occurs prior to inhibition of STAT1 phosphorylation. Another recent report showed inhibition of transcription of MHC class II by MCMV with normal STAT1 activation (15) similar to what we observed in HCMV. Whether the mechanism used by MCMV is similar to the one we describe in the present report remains to be investigated.

Our present data, which identify the defect in CIITA gene activation, also suggest that transcription of other genes which follow similar regulation, as shown for GBP, may be altered by HCMV infection. However, not all IFN-γ-inducible genes are expected to be the target of HCMV in view of normal up regulation of HLA class I synthesis in the presence of IFN-γ and HCMV. The mechanism involved in HLA-DR down regulation, which occurs upstream of CIITA and downstream of STAT1 activation, suggests transcription regulation by an immediate-early protein. Current studies in our laboratory are aimed at identifying this viral protein(s). In addition to helping to understand HLA class II transcription and HCMV regulation of transcription, the identification of such a protein would be useful in situations where targeted immunosuppression is required to down modulate exacerbated (autoimmunity) or nonappropriate (transplantation) MHC class II expression.

Although U373 MG cells are not bona fide APC, they are capable of processing and presenting endogenous Ag produced by infected cells when transfected with CIITA in the absence of IFN-γ treatment. Infection of cells by UV-irradiated HCMV did not activate CD4+ T-cell clones, showing that IE1 peptide was processed from neosynthesized protein in infected U373 MG-CIITA cells. Presentation of neosynthesized IE1 and cognate activation of infected cells by CD4+ anti-IE1 T lymphocytes has not been documented before. The role of IE1-specific CD4+ T cells could be the control of cognate, infected APC through release of anti-viral cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α. This effect may depend on the cell type and on the state of differentiation of cells, since IFN-γ and TNF-α have been shown to favor the differentiation and infection of macrophages (40). However, CD4+ T-cell clones produce cytokines other than IFN-γ and TNF-α which possess anti-HCMV activity and may reduce infection (10). Our data suggest that HCMV allows infected cells to escape from CD4+ recognition by blocking the required induction of HLA-DR.

In conclusion, we have shown, using U373 MG cells as a model, that HCMV escapes from anti-IE1 CD4+ T-lymphocyte response in vitro by interfering with the IFN-γ-mediated induction of HLA-DR at the level of CIITA induction. HCMV has evolved a number of stealth mechanisms which may account for a very high prevalence of HCMV infection in the population and latency in immunocompetent hosts. The modulation of the anti-IE1 CD4+ T-cell response is likely to play an important role in the host-HCMV balance. Further experiments are needed to demonstrate that the defect we describe here alters the functional CD4+ T-cell response in acute infections in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from INSERM and the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer. Emmanuelle Le Roy was financed by an M.E.S.R. fellowship.

We thank Sanofi Elf Biorecherche for the gift of recombinant IL-2, Susan Michelson and Marie-Christine Mazeron for kindly supplying reagents, Danièle Clément for technical assistance, and Claude de Préval, Justine Allan Yorke, and Paola Romagnoli for discussions.

Footnotes

This work is dedicated to the memory of our friend and colleague Claude de Préval.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn K, Angulo A, Ghazal P, Peterson P A, Yang Y, Früh K. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits antigen presentation by a sequential multistep process. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10990–10995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn K, Gruhler A, Galocha B, Jones T R, Wiertz E J, Ploegh H L, Peterson P A, Yang Y, Fruh K. The ER-luminal domain of the HCMV glycoprotein US6 inhibits peptide translocation by TAP. Immunity. 1997;6:613–621. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alp N J, Allport T D, Van Zanten J, Rodgers B, Sissons J G, Borysiewicz L K. Fine specificity of cellular immune responses in humans to human cytomegalovirus immediate-early 1 protein. J Virol. 1991;65:4812–4820. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4812-4820.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beninga J, Kropff B, Mach M. Comparative analysis of fourteen individual human cytomegalovirus proteins for helper T cell response. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:153–160. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-1-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briken V, Ruffner H, Schultz U, Schwarz A, Reis L F, Strehlow I, Decker T, Staeheli P. Interferon regulatory factor 1 is required for mouse Gbp gene activation by gamma interferon. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:975–982. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.2.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Britt W J, Alford C A. Cytomegalovirus. In: Fields B N, editor. Virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 2493–2523. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang C H, Fontes J D, Peterlin M, Flavell R A. Class II transactivator (CIITA) is sufficient for the inducible expression of major histocompatibility complex class II genes. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1367–1374. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darnell J E., Jr STATs and gene regulation. Science. 1997;277:1630–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davignon J-L, Clement D, Alriquet J, Michelson S, Davrinche C. Analysis of the proliferative T cell response to human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early protein (IE1): phenotype, frequency and variability. Scand J Immunol. 1995;41:247–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1995.tb03560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davignon J-L, Castanie P, Allan Yorke J A, Gautier N, Clement D, Davrinche C. Anti-human cytomegalovirus activity of cytokines produced by CD4+ T-cell clones specifically activated by IE1 peptides in vitro. J Virol. 1996;70:2162–2169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2162-2169.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davignon, J.-L., S. Michelson, and C. Davrinche. Presentation of human cytomegalovirus immediate-early (IE1) protein by astrocytoma cells to a CD4+ T cell clone, p. 139–144. In S. Michelson and S. A. Plotkin (ed.), Multidisciplinary approach to understanding cytomegalovirus disease. Elsevier Science Publishing, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 12.Forman S J, Zaia J A, Clark B R, Wright C L, Mills B J, Pottathil R, Racklin B C, Gallagher M T, Welte K, Blume K G. A 64,000 dalton matrix protein of human cytomegalovirus induces in vitro immune responses similar to those of whole viral antigen. J Immunol. 1985;134:3391–3395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Germain R N. MHC-dependent antigen processing and peptide presentation: providing ligands for T lymphocyte activation. Cell. 1994;76:287–299. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gueguen M, Long E O. Presentation of a cytosolic antigen by major histocompatibility complex class II molecules requires a long-lived form of the antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14692–14697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heise M T, Connick M, Virgin H W., IV Murine cytomegalovirus inhibits interferon gamma-induced antigen presentation to CD4 T cells by macrophages via regulation of expression of major histocompatibility complex class II-associated genes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1037–1046. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hengel H, Esslinger C, Pool J, Goulmy E, Koszinowski U H. Cytokines restore MHC class I complex formation and control antigen presentation in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2987–2997. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-12-2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hengel H, Koopmann J O, Flohr T, Muranyi W, Goulmy E, Hammerling G J, Koszinowski U H, Momburg F. A viral ER-resident glycoprotein inactivates the MHC-encoded peptide transporter. Immunity. 1997;6:623–632. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hobart M, Ramassar V, Goes N, Urmson J, Halloran P F. IFN regulatory factor-1 plays a central role in the regulation of the expression of class I and II MHC genes in vivo. J Immunol. 1997;158:4260–4269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones T R, Sun L. Human cytomegalovirus US2 destabilizes major histocompatibility complex class I heavy chains. J Virol. 1997;71:2970–2979. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2970-2979.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones T R, Wiertz E J, Sun L, Fish K N, Nelson J A, Ploegh H L. Human cytomegalovirus US3 impairs transport and maturation of major histocompatibility complex class I heavy chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11327–11333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones T R, Hanson L K, Sun L, Slater J S, Stenberg R M, Campbell A E. Multiple independent loci within the human cytomegalovirus unique short region down-regulate expression of major histocompatibility complex class I heavy chains. J Virol. 1995;69:4830–4841. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4830-4841.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonjic S, Mutter W, Weiland F, Reddehase M J, Koszinowski U H. Site-restricted persistent cytomegalovirus infection after selective long-term depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1199–1212. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.4.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kittlesen D J, Brown L R, Braciale V L, Sambrook J P, Gething M J, Braciale T J. Presentation of newly synthesized glycoproteins to CD4+ T lymphocytes. An analysis using influenza hemagglutinin transport mutants. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1021–1030. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee Y J, Benveniste E N. Stat1 alpha expression is involved in IFN-gamma induction of the class II transactivator and class II MHC genes. J Immunol. 1996;157:1559–1568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee Y J, Han Y, Lu H T, Nguyen V, Qin H, Howe P H, Hocevar B A, Boss J M, Ransohoff R M, Benveniste E N. TGF-beta suppresses IFN-gamma induction of class II MHC gene expression by inhibiting class II transactivator messenger RNA expression. J Immunol. 1997;158:2065–2075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehner P J, Karttunen J T, Wilkinson G W, Cresswell P. The human cytomegalovirus US6 glycoprotein inhibits transporter associated with antigen processing-dependent peptide translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6904–6909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X, Leung S, Qureshi S, Darnell J E, Jr, Stark G R. Formation of STAT1-STAT2 heterodimers and their role in the activation of IRF-1 gene transcription by interferon-alpha. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5790–5794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y N, Klaus A, Kari B, Stinski M F, Eckhardt J, Gehrz R C. The N-terminal 513 amino acids of the envelope glycoprotein gB of human cytomegalovirus stimulates both B- and T-cell immune responses in humans. J Virol. 1991;65:1644–1648. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1644-1648.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu H T, Riley J L, Babcock G T, Huston M, Stark G R, Boss J M, Ransohoff R M. Interferon (IFN) beta acts downstream of IFN-gamma-induced class II transactivator messenger RNA accumulation to block major histocompatibility complex class II gene expression and requires the 48-kD DNA-binding protein, ISGF3-gamma. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1517–1525. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mach B, Steimle V, Martinez-Soria E, Reith W. Regulation of MHC class II genes: lessons from a disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:301–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meraz M A, White J M, Sheehan K C, Bach E A, Rodig S J, Dighe A S, Kaplan D H, Riley J K, Greenlund A C, Campbell D, Carver-Moore K, DuBois R N, Clark R, Aguet M, Schreiber R D. Targeted disruption of the Stat1 gene in mice reveals unexpected physiologic specificity in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Cell. 1996;84:431–442. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller D M, Rahill B M, Boss J M, Lairmore M D, Durbin J E, Waldman J W, Sedmak D D. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits major histocompatibility complex class II expression by disruption of the Jak/Stat pathway. J Exp Med. 1998;187:675–683. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muhlethaler-Mottet A, Otten L A, Steimle V, Mach B. Expression of MHC class II molecules in different cellular and functional compartments is controlled by differential usage of multiple promoters of the transactivator CIITA. EMBO J. 1997;16:2851–2860. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muhlethaler-Mottet A, Di Berardino W, Otten L A, Mach B. Activation of the MHC class II transactivator CIITA by interferon-gamma requires cooperative interaction between Stat1 and USF-1. Immunity. 1998;8:157–166. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nandan D, Reiner N E. TGF-beta attenuates the class II transactivator and reveals an accessory pathway of IFN-gamma action. J Immunol. 1997;158:1095–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pieters J. MHC class II restricted antigen presentation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinnan G V, Jr, Kirmani N, Rook A H, Manischewitz J F, Jackson L, Moreschi G, Santos G W, Saral R, Burns W H. Cytotoxic T cells in cytomegalovirus infection: HLA-restricted T-lymphocyte and non-T-lymphocyte cytotoxic responses correlate with recovery from cytomegalovirus infection in bone-marrow-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:7–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198207013070102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sedmak D D, Guglielmo A M, Knight D A, Birmingham D J, Huang E H, Waldman W J. Cytomegalovirus inhibits major histocompatibility class II expression on infected endothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:683–692. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shuai K, Schindler C, Prezioso V R, Darnell J E., Jr Activation of transcription by IFN-gamma: tyrosine phosphorylation of a 91-kD DNA binding protein. Science. 1992;258:1808–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1281555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soderberg-Naucler C, Fish K N, Nelson J A. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha specifically induce formation of cytomegalovirus-permissive monocyte-derived macrophages that are refractory to the antiviral activity of these cytokines. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:3154–3163. doi: 10.1172/JCI119871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steimle V, Siegrist C A, Mottet A, Lisowska-Grospierre B, Mach B. Regulation of MHC class II expression by interferon-gamma mediated by the transactivator gene CIITA. Science. 1994;265:106–109. doi: 10.1126/science.8016643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steimle V, Otten L A, Zufferey M, Mach B. Complementation cloning of an MHC class II transactivator mutated in hereditary MHC class II deficiency (or bare lymphocyte syndrome) Cell. 1993;75:135–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Heyningen V, Guy K, Newman R, Steel C M. Human MHC class II molecules as differentiation markers. Immunogenetics. 1982;16:459–469. doi: 10.1007/BF00372104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walter E A, Greenberg P D, Gilbert M J, Finch R J, Watanabe K S, Thomas E D, Riddell S R. Reconstitution of cellular immunity against cytomegalovirus in recipients of allogeneic bone marrow by transfer of T-cell clones from the donor. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1038–1044. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510193331603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiertz E J, Jones T R, Sun L, Bogyo M, Geuze H J, Ploegh H L. The human cytomegalovirus US11 gene product dislocates MHC class I heavy chains from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol. Cell. 1996;84:769–779. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiertz E, Hill A, Tortorella D, Ploegh H. Cytomegaloviruses use multiple mechanisms to elude the host immune response. Immunol Lett. 1997;57:213–216. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(97)00073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wiertz E, Tortorella D, Bogyo M, Yu J, Mothes W, Jones T R, Rapoport T A, Ploegh H L. Sec61-mediated transfer of a membrane protein from the endoplasmic reticulum to the proteasome for destruction. Nature. 1996;384:432–438. doi: 10.1038/384432a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]