Abstract

CXCR4 is a chemokine receptor and a coreceptor for T-cell-line-tropic (X4) and dual-tropic (R5X4) human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) isolates. Cells coexpressing CXCR4 and CD4 will fuse with appropriate HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein (Env)-expressing cells. The delineation of the critical regions involved in the interactions within the Env-CD4-coreceptor complex are presently under intensive investigation, and the use of chimeras of coreceptor molecules has provided valuable information. To define these regions in greater detail, we have employed a strategy involving alanine-scanning mutagenesis of the extracellular domains of CXCR4 coupled with a highly sensitive reporter gene assay for HIV-1 Env-mediated membrane fusion. Using a panel of 41 different CXCR4 mutants, we have identified several charged residues that appear important for coreceptor activity for X4 Envs; the mutations E15A (in which the glutamic acid residue at position 15 is replaced by alanine) and E32A in the N terminus, D97A in extracellular loop 1 (ecl-1), and R188A in ecl-2 impaired coreceptor activity for X4 and R5X4 Envs. In addition, substitution of alanine for any of the four extracellular cysteines alone resulted in conformational changes of various degrees, while mutants with paired cysteine deletions partially retained their structure. Our data support the notion that all four cysteines are involved in disulfide bond formation. We have also identified substitutions which greatly enhance or convert CXCR4’s coreceptor activity to support R5 Env-mediated fusion (N11A, R30A, D187A, and D193A), and together our data suggest the presence of conserved extracellular elements, common to both CXCR4 and CCR5, involved in their coreceptor activities. These data will help us to better detail the CXCR4 structural requirements exhibited by different HIV-1 strains and will direct further mutagenesis efforts aimed at better defining the domains in CXCR4 involved in the HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion process.

Infection of CD4-expressing cells by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) requires the participation of a coreceptor molecule which in concert with CD4 interacts with the envelope glycoprotein (Env) (for reviews, see references 10, 20, and 36). This trimolecular interaction is generally believed to be the initial step in Env-mediated membrane fusion and virus infection. These coreceptor molecules have been shown to be members of the chemokine receptor family of seven-transmembrane-domain G-protein-coupled receptors (7TMGPCRs). A proposed model for HIV cellular tropism has been based on the fusogenic preferences of a particular isolate’s Env for cell types that express alternate host factors. Indeed, it appears that the tropism of an individual HIV-1 strain can be largely attributed to its Env’s specificity for a particular coreceptor molecule, with CXCR4 being used by T-cell-line-tropic (T-tropic) or X4 (5) isolates and CCR5 being used by macrophage-tropic or R5 isolates. It is also evident that many primary HIV-1 isolates are in fact dual tropic, having the ability to utilize both CXCR4 and CCR5 as coreceptors, and have been designated R5X4 isolates (5). Some dual-tropic isolates have shown the ability to utilize one or more of 13 other related 7TMGPCRs (reviewed in reference 22). In addition, there have been several recent reports that some primary and T-cell-line-adapted X4 isolates, unlike most T-cell-line-adapted X4 isolates, are capable of utilizing CXCR4 in primary human macrophages, although the data are not in complete agreement (37, 50, 51, 57, 62).

An important question relates to the regions in CXCR4 and CCR5 that are critical for the association of these coreceptors with the Env-CD4 complex. The delineation of the critical regions in CXCR4 and CCR5 involved in these interactions is presently under intensive investigation. To date there have been a number of studies employing chimeric coreceptor molecules as a means to identify the important domains involved in coreceptor activity for both CXCR4 and CCR5, with the majority of the work focusing on the latter. The importance of a particular region in CXCR4 for Env-mediated fusion was first suggested by Feng et al. (27) from experiments showing that a polyclonal rabbit antiserum to the CXCR4 amino (N) terminus blocked Env-mediated cell fusion and virus infection. A second report demonstrated that the N terminus of CXCR4 was indeed required for some isolates yet was not the sole element deemed important, which was not surprising in light of the information obtained from the CCR5 studies (43). Two additional studies independently highlighted the importance of additional extracellular domains of CXCR4, primarily the second extracellular loop (ecl-2), in coreceptor activity (8, 34). However, the N terminus appeared dispensable for at least one X4 HIV-1 isolate (LAI) (8). These studies also showed no apparent dependency on CXCR4 signaling for membrane fusion and virus entry nor for any requirement of the potential glycosylation sites of the molecule. Taken together, these studies have indicated that the interactions of the coreceptors with Env and CD4 are structurally complex, and multiple extracellular domains appear important or are directly involved. However, it remains possible that many of the chimeric receptor molecules studied to date are functional due to compensatory conditions caused by distal regions of the background receptor first proposed by Moore and colleagues (36). This may result in important CXCR4 and CCR5 regions being overlooked. Adding further complexity to this system, it seems that different viral isolates’ Envs have alternate individual structural requirements for a given coreceptor molecule. This last notion may also relate to the observations that some R5X4 and X4 isolates are able to utilize macrophage-expressed CXCR4 while others cannot. Thus, the molecular determinants of the chemokine receptors that are important for coreceptor activity in Env-mediated fusion are not yet well defined.

In the present study, we employed a site-directed mutagenesis strategy, primarily by alanine-scanning mutagenesis, in an attempt to define in greater detail the critical residues or domains in CXCR4 required for its coreceptor activity in HIV-1 Env-mediated membrane fusion. We initially targeted both positively and negatively charged residues in the extracellular domains of CXCR4, but as preliminary data were obtained and analyzed, the CXCR4 mutation panel was expanded to include a number of additional constructs. A preliminary report of these data was presented previously (13).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and culture conditions.

Human HeLa, monkey BS-C-1, mouse 3T3, and rabbit RK13 cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md., while human glioblastoma cell line U373-MG and the U373-MG-CD4+ derivative cell line were provided by Adam P. Geballe, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Wash. (30). Cell cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cultures were maintained in the following media: for HeLa, 3T3, U373MG, and U373MG-CD4 cell monolayers, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Quality Biologicals, Gaithersburg, Md.) supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum (BCS), 2 mM l-glutamine, and antibiotics (DMEM-10); for BS-C-1 and RK13 cell monolayers, Eagle’s minimum essential medium (Quality Biologicals) supplemented with 10% BCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, and antibiotics (EMEM-10). The U373-MG-CD4+ cell monolayers were also supplemented with 200 μg of G418 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.)/ml.

Plasmids and recombinant vaccinia viruses.

For Env expression, we employed a battery of recombinant vaccinia viruses encoding the Env genes from several R5, X4, and R5X4 HIV-1 isolates. The following recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing gp160 from different HIV-1 isolates (names in parentheses) were used: vSC60 (BH8) (14), vCB-28 (JR-FL), vCB-32 (SF162), vCB-34 (SF2), vCB-39 (ADA), vCB-40 (IIIB/BH10), vCB-41 (LAV), vCB-43 (Ba-L) (9), and vDC-1 (HIV-1 isolate 89.6 [16] gp160 linked to a strong synthetic vaccinia virus early-late promoter [pSC59] [14]). The following recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing gp160 from different simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) isolates were used: vCB-74 (mac239), vCB-74 (mac316), and vCB-76 (mac316mut) (24). Purified vaccinia virus stocks were used at a multiplicity of infection of 10 PFU/cell. For CD4 expression, we used recombinant vaccinia virus vCB-3 (12). Bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase was produced by infection with vTF1-1 (P11 natural late vaccinia virus promoter) (2). The Escherichia coli lacZ gene linked to the T7 promoter was introduced into cells by infection with vaccinia virus recombinant vCB21R-LacZ, which was described previously (3). For coreceptor expression, we employed two alternative plasmid expression protocols. For cell fusion assays, we transfected cell monolayers with plasmids containing coreceptor genes linked to a strong synthetic vaccinia virus early-late promoter (pSC59) (14) followed by infection 2 h later with the Western Reserve (WR) wild-type strain of vaccinia virus, and transfection of monolayers was performed with DOTAP (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). For virus infection assays, cells were transfected with coreceptor genes linked to the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter in pCDNA3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.), and transfection was performed by the calcium phosphate precipitate procedure, using a Profection mammalian transfection kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.).

Mutagenesis.

CCR5 and CXCR4 mutations were made by using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Two mutagenic polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis-purified oligonucleotides were used per mutation. The identities of all CXCR4 mutant constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Cell surface expression.

Wild-type and mutant CXCR4 expression levels were determined by fluorescent-antibody staining. Target cells were transfected as described above, infected with vCB-3 for 2 h at 37°C, and incubated overnight at 31°C in medium containing rifampin (100 μg/ml). Following overnight incubation, cells (0.5 × 106 to 1.0 × 106) were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and once with PBS containing 2.5% goat serum on ice. Cells were stained in 100 μl of PBS containing 2.5% normal rabbit serum and 2 μg of 12G5 or 4G10 mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb) to CXCR4/100 μl for 1 h on ice. Cells were then washed three times with PBS, stained in 100 μl of PBS containing 2.5% goat serum and 10 μl of phycoerythrin-labeled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) for 45 min, washed three times with PBS, and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Fluorescence was measured with an EPIC XL flow cytometer (Coulter, Miami, Fla.).

Cell-cell fusion assays.

Fusion between Env-expressing and receptor-expressing cells was measured by a reporter gene assay in which the cytoplasm of one cell population contains vaccinia virus-encoded T7 RNA polymerase and the cytoplasm of the other contains the E. coli lacZ gene linked to the T7 promoter; β-galactosidase (β-Gal) is synthesized in fused cells (39). Vaccinia virus-encoded proteins were produced by incubating infected cells at 31°C overnight (6). Cell-cell fusion reactions were conducted with the various cell mixtures in 96-well plates at 37°C. Typically, the ratio of CD4-expressing to Env-expressing cells was 1:1 (2 × 105 total cells per well, 0.2-ml total volume). Cytosine arabinoside (40 μg/ml) was added to the fusion reaction mixture to reduce nonspecific β-Gal production (6). For quantitative analyses, Nonidet P-40 was added (0.5% final) at 2.5 h and aliquots of the lysates were assayed for β-Gal at ambient temperature with the substrate chlorophenol red–β-d-galactopyranoside (CPRG; Boehringer Mannheim). For syncytium assays, cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet 6 h after being mixed. Fusion results were calculated and expressed as rates of β-Gal activity (change in optical density at 570 nm per minute × 1,000) (39). For comparisons of mutant CXCR4s to wild-type CXCR4, mutant coreceptor activities were first corrected for any difference in the level of surface expression compared to that of wild-type CXCR4 and then the percentage of coreceptor activity (i.e., the percentage of wild-type activity retained) for a given mutant CXCR4 was calculated by regarding the activity observed by wild-type CXCR4 in the same experiment as 100%. Thus, the average percentage of activity derived from three independent experiments was calculated and the range of those percentages was indicated. Each mutant CXCR4 was tested at least three times in the U373-MG cell line as well as several other nonhuman cell lines.

HIV-1 infection studies.

Viral infection assays were performed with a luciferase reporter HIV-1 Env pseudotyping system (17). Viral stocks were prepared as previously described by transfecting 293T cells with plasmids encoding the luciferase virus backbone (pNL-Luc-E−R−) and Env from HIV strain JR-FL (40), Ba-L (32), SF162 (15), NL4-3 (LAV) (1, 46), or HXB2 (41, 48). The resulting supernatant was clarified by centrifugation for 10 min at 2,000 rpm in a Sorvall RT-7 centrifuge (RTH-750 rotor) and stored in 30% BCS at −80°C. For infection, U373-MG-CD4 cells were prepared in 48-well plates and transfected with the desired coreceptor-encoding plasmid by calcium phosphate precipitation. The medium was changed after 16 h, and cells were infected the next day with 50 μl of viral supernatant plus 150 μl of DMEM-10 containing 1.6 μg of DEAE-dextran. DMEM-10 (0.3 ml) was added to each well the following day. Cells were lysed at 4 days postinfection by resuspension in 50 μl of cell lysis buffer (Promega), and 50 μl of the resulting lysate was assayed for luciferase activity, using luciferase substrate (Promega).

RESULTS

Generation and expression of mutant CXCR4 molecules.

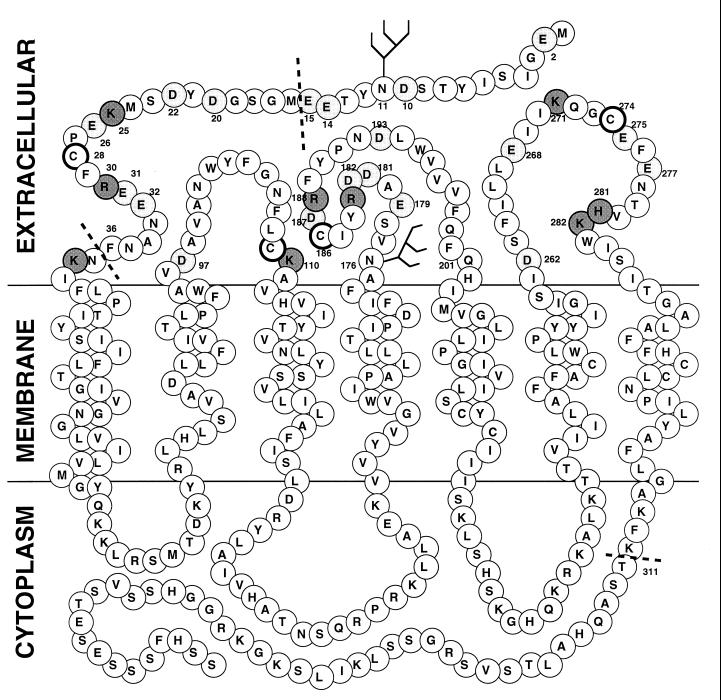

It has been established in numerous reports that a major determinant of HIV-1 cellular tropism for infection is Env, with special emphasis on a role for the V3 loop of gp120 (for reviews, see references 35 and 44). More recently, these earlier observations have led to the development of a model for Env-CD4-coreceptor interaction in which the V3 loop is proposed to directly interact with CXCR4 or CCR5 (19), with the notion that the electrostatic charge of the V3 loop may be an important factor in this interaction (20). Indeed, there is strong evidence that this is the case for the gp120-CCR5 association (55, 59), in which an R5 isolate’s gp120 can compete with CCR5 for macrophage inflammatory protein 1β (a natural CCR5 ligand) binding while the gp120 lacking the V3 loop cannot. Because of these observations, we initially focused our mutagenesis efforts on the predicted charged extracellular residues in CXCR4. We chose an alanine-scanning mutagenesis strategy, in this case charged-to alanine scanning mutagenesis (29), because it is a well-accepted technique for mapping or identifying residues potentially involved in particular protein-protein interactions. Shown in Fig. 1 is a representation of the CXCR4 molecule indicating the locations of the altered amino acid residues used in the present study. In addition to charged amino acid substitutions, we also included a set of alanine substitutions for the four extracellular cysteine residues in both single and paired configurations, two N-terminal deletion constructs, and alanine substitutions for the two asparagine residues predicted to be sites of N-linked glycosylation. One point mutation, a substitution of alanine for the phenylalanine at position 201 (F201A), was made by mischance but was still included in this study.

FIG. 1.

Bubble diagram of CXCR4. Predicted extracellular, transmembrane, and cytoplasmic regions are indicated. Residues that have been altered are numbered. Acidic residues are lightly shaded; basic residues are darkly shaded. Extracellular cysteines are highlighted with bold circles. Dashed lines indicate positions where N-terminal deletions were made.

Depending on the assay employed, we expressed coreceptor genes by using a vaccinia virus promoter- or a CMV promoter-based system with a plasmid transfection protocol. With few exceptions, most notably some of the cysteine substitution mutants, analysis of cell surface expression by cell surface antibody staining and flow cytometry indicated that the majority of the mutant CXCR4s in our panel were expressed at levels comparable to wild-type CXCR4 (Tables 1 and 2). While elimination of amino acids 2 through 16 (N-term del-15) did not sharply reduce CXCR4 expression, expression was drastically reduced by elimination of amino acids 2 through 37 (N-term del-36) from the N-terminal domain. A double alanine substitution at the N terminus, E14A E31A, also resulted in drastically reduced surface expression, whereas each of these mutations individually resulted in approximately wild-type levels of cell surface expression. Several other combinations of mutations were attempted, but the resulting mutants had poor surface expression and were not included in our analysis (data not shown). However, for the purposes of quantifying coreceptor activity and comparing the mutant CXCR4s to wild-type CXCR4, all cell-cell fusion data (Fig. 2) were first corrected for variations in cell surface expression; i.e., a particular mutant exhibiting a marked reduction in coreceptor activity yet being poorly expressed compared to wild-type CXCR4 could potentially be misleading.

TABLE 1.

Cell surface expression of CXCR4 mutant constructsa

| CXCR4 mutation(s) | % Expression of CXCR4

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Avg | Range (n = 3) | |

| E2A | 80 | 78–82 |

| D10A | 113 | 112–115 |

| N11A | 115 | 66–164 |

| E14A | 151 | 133–173 |

| E15A | 160 | 134–203 |

| D20A | 92 | 91–94 |

| D22A | 78 | 62–97 |

| K25A | 81 | 45–177 |

| E26A | 96 | 91–102 |

| R30A | 89 | 60–118 |

| E31A | 86 | 75–98 |

| E32A | 127 | 118–136 |

| D97A | 172 | 144–201 |

| K110A | 73 | 62–82 |

| N176A | 91 | 72–111 |

| E179A | 98 | 85–112 |

| D181A | 76 | 67–86 |

| D182A | 70 | 51–89 |

| D187A | 110 | 108–113 |

| R188A | 99 | 94–106 |

| D193A | 87 | 87–88 |

| F201A | 118 | 91–146 |

| D262A | 83 | 65–101 |

| E268A | 73 | 43–103 |

| K271A | 78 | 70–87 |

| E275A | 113 | 86–141 |

| E277A | 84 | 58–110 |

| H281A | 113 | 86–140 |

| K282A | 102 | 92–112 |

| N11A D187A | 102b | |

| E14A E31A | 10b | |

| N-term del-15 | 70 | 59–79 |

| N-term del-36 | 19 | 17–22 |

| DRY133-135 | 2b | |

| C-term del-42 | 91b | |

Cell surface expression of CXCR4 mutant constructs. U373 cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant CXCR4 in the pSC59 vaccinia virus vector. Cells were then infected with wild-type vaccinia virus (WR), incubated with anti-CXCR4 MAb (12G5), and stained with phycoerythrin–anti-mouse IgG. Mean fluorescence intensities were determined with a flow cytometer (model XL-MCL; Coulter, Miami, Fla.). Values for mutant CXCR4s are percentages of the mean fluorescence intensity of wild-type CXCR4, which is regarded as 100%. The averages of values from three experiments and the ranges of those percentages are shown.

Single measurement.

TABLE 2.

Cell surface expression of CXCR4 cysteine mutant constructsa

| CXCR4 mutation(s) | % of wild-type activity with MAb

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 12G5 | 4G10 | |

| C28A | 30 | 112 |

| C109A | 5 | 0 |

| C186A | 0 | 0 |

| C274A | 26 | 108 |

| C28A C274A | 53 | 113 |

| C109A C186A | 8 | 13 |

Cell surface expression of CXCR4 cysteine mutant constructs. U373 cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant CXCR4 in the pSC59 vaccinia virus vector. Cells were then infected with wild-type vaccinia virus (WR), incubated with anti-CXCR4 MAb (4G10 or 12G5), and stained with phycoerythrin–anti-mouse IgG. Mean fluorescence intensities were determined with a flow cytometer (model XL-MCL; Coulter, Miami, Fla.). Values for mutant CXCR4s are percentages of the mean fluorescence intensity of wild-type CXCR4, which is regarded as 100%.

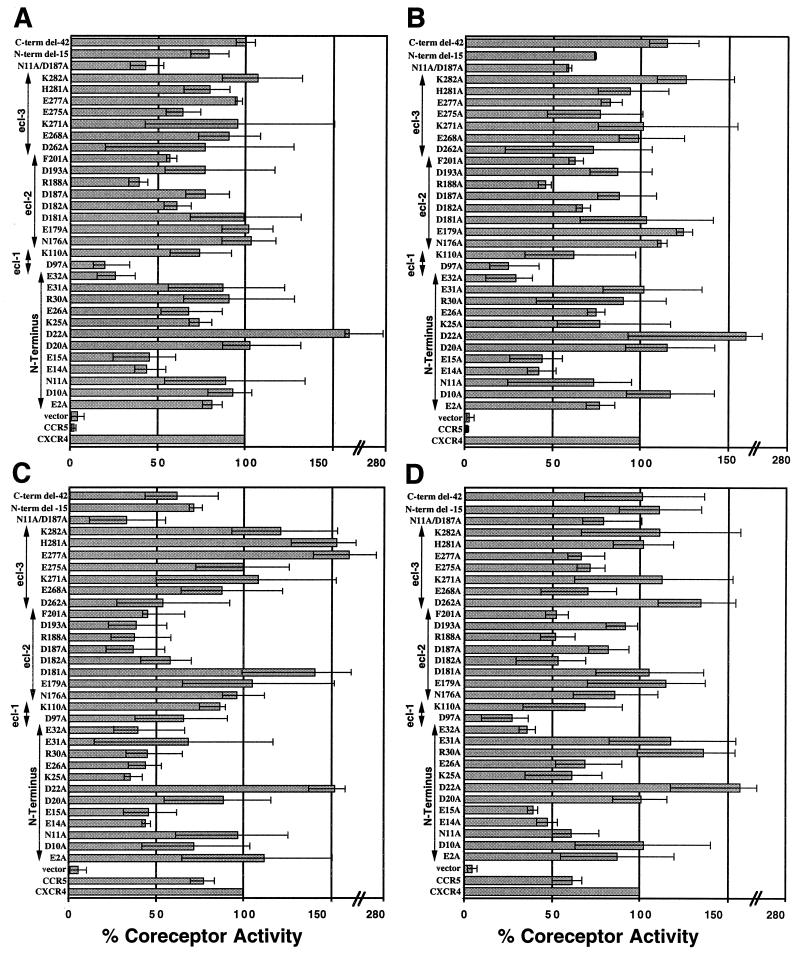

FIG. 2.

Coreceptor function of mutant CXCR4s in cell-cell fusion assays with T-tropic (X4) and dual-tropic (R5X4) HIV-1 Envs. U373 target cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding the wild-type or a mutant CXCR4 gene linked to a vaccinia virus promoter and infected with vCB21R-LacZ and vCB-3 (CD4). HeLa Env-expressing effector cells were infected with a vaccinia virus encoding T7 polymerase (vTF1-1) and one encoding LAV (vCB-41) (A), IIIB/BH10 (vCB-40) (B), SF2 (vCB-34) (C), or 89.6 (vDC-1) (D). Duplicate cell mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 2.5 h. Fusion was assessed by measurement of β-Gal in detergent lysates of cells. The activities of the mutant CXCR4s are presented as percentages of wild-type CXCR4 activity after adjustment for the level of cell surface expression as detailed in Materials and Methods. Each mutant CXCR4 construct was tested in duplicate three times. The averages of these results are shown in the figure. The error bars in the figure represent the ranges of those three calculated percentages.

Coreceptor activities of mutant CXCR4s for X4 Envs.

We used a well-characterized cell-cell fusion assay to determine coreceptor function for a panel of 32 CXCR4 mutants. Vaccinia virus-encoded HIV-1 Envs were expressed in HeLa effector cells coinfected with a vaccinia virus encoding the E. coli lacZ gene linked to the T7 promoter (vCB21R-LacZ). U373 target cells were transfected with plasmids containing wild-type or a mutant CXCR4 gene linked to a vaccinia virus promoter. After overnight expression, target and effector cells were mixed and fusion was allowed to proceed for 2.5 h and assessed as described in Materials and Methods. Results (Fig. 2) have been adjusted to reflect cell surface expression levels, as determined by flow cytometry analysis with 12G5, a conformation-dependent MAb to CXCR4, and the data are presented as an average of the percentages of wild-type CXCR4 coreceptor activity derived from three independent experiments performed in duplicate. The bars in the Fig. 2 data represent the range of the three calculated percentages over their average since the data are a calculation based on wild-type CXCR4 activity being arbitrarily regarded as 100%. For the X4 Envs LAV and IIIB (23) (Fig. 2A and B, respectively) and the R5X4 Envs SF2 and 89.6 (23) (Fig. 2C and D, respectively), we found a >50% reduction in coreceptor activity for mutants with substitutions of three alanines for the negatively charged glutamic acid residues in the N terminus (E14A, E15A, and E32A). Previously, we proposed that the N terminus of CXCR4 may play a role in the HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion event, based on studies demonstrating that a rabbit polyclonal antiserum raised against a synthetic peptide corresponding to the entire predicted extracellular domain blocked both CXCR4-supported cell-cell fusion and virus infection (27). The present results further support this initial observation and suggest that several negatively charged residues may be specifically involved, perhaps by directly associating with elements in Env. Unfortunately, further analysis of a double mutant (E14A E31A) showed that the coreceptor was not expressed on the cell surface at high enough levels to warrant any additional supportive conclusions as to the importance of these negatively charged N-terminal residues in CXCR4 coreceptor activity. We also analyzed two N-terminal deletion CXCR4 mutant constructs, one 36 and the other 15 residues in length. The 36-residue N-terminal deletion CXCR4 mutant was poorly expressed, being only 19% of the level of wild-type CXCR4, and we felt that it was unsuitable for inclusion in our analysis. However, the 15-residue N-terminal deletion CXCR4 mutant was expressed on the cell surface at about 70% the level of wild-type CXCR4 (Table 1) but was only moderately defective in coreceptor activity, with the exception of Env 89.6.

CXCR4 is capable of signal transduction after appropriate ligand stimulation. The C terminus is rich in conserved serine and threonine residues, which represent potential phosphorylation sites for the family of G-protein-coupled receptor kinases, and there is a conserved DRY motif in intracellular loop 2 which is believed to be a site of G protein interaction (for a review, see reference 45). Our substitution mutant from which the DRY sequence was removed was not expressed on the cell surface (Table 1). However, we found no diminution in CXCR4 coreceptor activity with a 42-residue C-terminal deletion mutant, suggesting that this domain has no role in Env-mediated fusion in cell lines, findings in agreement with others (8, 34).

The analysis of charged-residue mutations in ecl-1 of CXCR4 identified additional important residues. ecl-1 of CXCR4 is the smallest of the three outside loops and possesses only two charged residues (Fig. 1). Mutagenesis of the negatively charged aspartic acid (D97A) potently abrogated coreceptor function for X4 Envs LAV and IIIB, as well as for the R5X4 Env 89.6. Indeed, for these three Envs, the D97A mutation was the most potent single CXCR4 alteration found in this panel, being slightly better at inhibiting coreceptor activity than any of the glutamic acid residues in the molecule’s N terminus (Fig. 2A, B, and D), whereas elimination of the single positively charged residue in ecl-1 (K110A) had little effect. The SF2 Env (Fig. 2C) appeared unaffected in the ability to employ these ecl-1 mutant CXCR4s as functional coreceptors. These results support the notion of a significant role for ecl-1 of CXCR4 in both X4 and one R5X4 Env-mediated fusions.

Mutagenesis of ecl-2 and ecl-3 of CXCR4 yielded more-variable results (Fig. 2). Only replacement of the positively charged arginine residue in ecl-2 (R188A) resulted in significantly reduced fusion activity for all four Envs examined. Although some other individual mutations of both positively and negatively charged residues in ecl-2 and ecl-3 had minor inhibitory effects on coreceptor activity for LAV, IIIB, or 89.6, we did not observe any consistent pattern, and in no case was the inhibition equal to or greater than 50%. We also included a single point mutation of a phenylalanine in ecl-2 that was made in error and found that the resulting mutant exhibited about a 50% reduction in coreceptor activity for all Envs examined. In general, our results with LAV, IIIB, and 89.6 were quite similar, but as a set they differed somewhat from the results achieved with SF2, the second R5X4 Env. A number of additional single-amino-acid substitutions caused reduced coreceptor activity specifically with the SF2 Env: E26A and K25A in the N terminus and D187A and D193A in ecl-2. As a whole, the data suggest that SF2 appears more dependent on ecl-2 than on ecl-1 in conjunction with the N terminus. These observations indicate that an individual Env may exhibit specific or somewhat unique coreceptor structure dependencies.

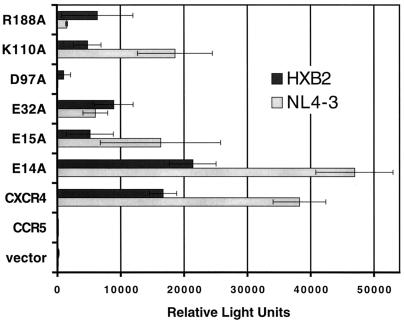

While the HIV-1 Env-mediated cell-cell fusion assay presents a reliable model of HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion and receptor function (6), we tested many of the CXCR4 mutations that resulted in defective coreceptor activities in HIV-1 virus infection assays as well. We transfected U373-CD4+ cells with plasmids encoding wild-type or mutant CXCR4 linked to a CMV promoter and, following a period of expression, infected the cells with luciferase reporter gene–HIV-1 Env pseudoviruses using the HXB2 or NL4-3 Env. These results showed that four of the five CXCR4 mutants (E15A, E32A, D97A, and R188A) that consistently exhibited a significantly reduced ability to support Env-mediated fusion in the cell-cell fusion assay also had reduced activities in this virus infection assay (Fig. 3). The E14A mutant was the exception, supporting infection at wild-type levels. Additionally, the replacement of lysine in ecl-1 (K110A), resulting in 60 to 75% of wild-type activity in the fusion assays, depending on the Env tested, also caused significant impairment of coreceptor activity for virus infection (Fig. 3). We also consider it noteworthy that the magnitudes of reduction of any one mutant CXCR4 are quite similar for these two very different assays even though the levels of coreceptor expression for the vaccinia virus promoter- and CMV promoter-based systems are different. Also, unlike the data in Fig. 2, and due to the assay requirements, no correction of surface expression levels has been made in the data presented in Fig. 3, even though some of the mutant CXCR4s (D97A and E15A) are expressed on the cell surface at levels higher than those of wild-type CXCR4.

FIG. 3.

Coreceptor function of mutant CXCR4 in virus infection assays with X4 HIV-1 Envs. U373-CD4+ cells were transfected with a plasmid (pCDNA3) encoding the indicated wild-type coreceptor (CXCR4 or CCR5) or mutant CXCR4. Wells of cells (in triplicate) were infected with the indicated HIV-1 Env luciferase reporter virus. Infection was assessed on day 4 by measuring the amounts of luciferase activity in cell lysates. The luciferase activities shown were obtained from separate samples in the same experiment. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of the mean values for triplicate wells. This experiment was repeated three times, and the data from a representative experiment are shown in the figure.

Taken together, these results indicate that negatively charged acidic residues in the N terminus and ecl-1 are required for optimal coreceptor activity for several T-tropic X4 and R5X4 Envs. These amino acids appeared to be the most important of the charged residues examined because their elimination resulted in a marked reduction (greater than 50%) of CXCR4 coreceptor activity for all Envs tested. Also, an additional positively charged residue in ecl-2 was important for coreceptor activity as well. We interpret the latter observation as evidence that the site of interaction between the CXCR4 coreceptor and HIV-1 Env is most likely a complex, three-dimensional array of specific contact sites dependent on both positively and negatively charged residues in the molecule’s extracellular domains. In summary, the loss of activity associated with a loss of acidic residues supports the hypothesis that Env tropism is determined, at least in part, by ionic interactions between the extracellular domains of CXCR4 and Env; mutation of the Env V3 loop to a more positive overall charge has been associated with a shift from R5 to X4 coreceptor usage (18, 28). Similar results were obtained with this panel of mutants when expressed in BS-C-1, 3T3, and RK-13 cells (data not shown).

Coreceptor activities of mutant CXCR4s for R5 Envs.

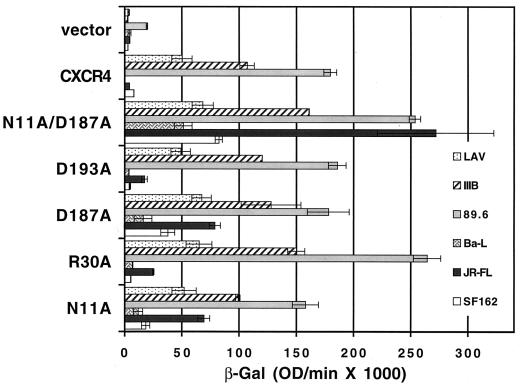

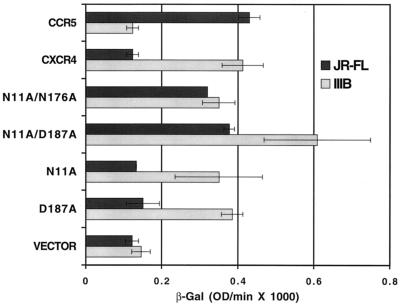

During the course of our cell-cell fusion experiments, we included prototypic R5 HIV-1 Env-expressing effector cells as one of our negative controls, and unexpectedly we found four amino acids in CXCR4, out of the entire panel, which when replaced by alanine allowed CXCR4 to serve as a coreceptor for an R5 Env. These residues were in the N terminus (N11A and R30A) and in ecl-2 (D187A and D193A), and they consistently supported fusion, over background, with JR-FL as well as several other prototypic R5 Envs, SF162, Ba-L (Fig. 4), and ADA (data not shown) (23). This phenomenon was not an artifact of the target cell line, since similar results were seen with monkey BSC-1, human U373-CD4+, mouse 3T3, and rabbit RK13 cells (data not shown). This activity could be blocked by 12G5 antibody to CXCR4 (data not shown). The two most potent single-amino-acid alterations were D187A and N11A, with the D187A mutation being the more potent of the two. The importance of the D187 residue, upon replacement by valine or alanine, in allowing CXCR4 usage by HIV-1 R5 Envs was also recently reported by Wang et al. (58), who performed mutagenesis of ecl-2 of CXCR4 and used a similar cell-cell fusion assay employing the same HIV-1 Env-encoding recombinant vaccinia viruses. When combined, our two most potent mutants, D187A and N11A, showed a greater than additive effect in supporting R5 Env-mediated fusion. As shown in Fig. 4, the N11A D187A mutant supported a JR-FL Env-mediated cell-cell fusion activity that exceeded the activities produced by the X4 Envs LAV and IIIB with either wild-type CXCR4 or the N11A D187A mutant.

FIG. 4.

Coreceptor function of mutant CXCR4s that support R5 Env fusion. BS-C-1 target cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding wild-type CXCR4 or the indicated mutant CXCR4 construct linked to a vaccinia virus promoter and infected with vCB21R-LacZ and vCB-3 (CD4). HeLa effector cells were infected with vTF-1 and either LAV (vCB-41), IIIB/BH10 (vCB-40), 89.6 (vDC-1), Ba-L (vCB-43), JR-FL (vCB-28), or SF162 (vCB-32). Duplicate cell mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 2.5 h. Fusion was assessed by measurement of β-Gal in detergent lysates of cells. The rates of β-Gal activity shown were obtained from separate samples in the same experiment. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of the mean values obtained for duplicate fusion assays. This experiment was performed three times, and the data from a representative experiment are shown in the figure. OD, optical density.

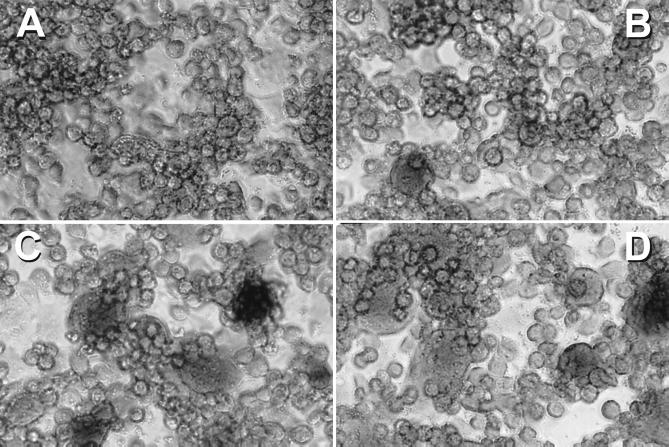

To ensure that the cell-cell fusion we were observing between R5 Env-expressing cells and the mutant CXCR4 CD4+ cells was equivalent to that observed for any X4 Env-mediated fusion event and was not in some way restricted to an early fusion intermediate, such as a fusion pore (38), that was simply allowing for the activation of the lacZ reporter system via the transfer of T7 polymerase, we also performed syncytium assays with these mutant CXCR4s. The results from these experiments paralleled the cell-cell fusion assay findings (Fig. 5). Syncytia formed when U373-CD4+ cells expressing coreceptor were mixed with HeLa cells expressing the HIV-1 R5 JR-FL Env (Fig. 5B), and syncytia were much larger with U373-CD4+ cells expressing the N11A D187A mutant CXCR4 than with cells expressing the D187A mutant (Fig. 5C). Indeed, syncytium formation with the N11A D187A mutant CXCR4 was essentially equivalent to that of U373-CD4+ cells expressing CCR5 (Fig. 5D). Because of these surprising results, we thought it important to examine some SIV Envs for the ability to employ these R5 Env fusion-supporting CXCR4 mutants as functional coreceptors, since all SIV Envs examined to date have been shown to be CCR5 dependent. We found that none of the CXCR4 mutants that could function for HIV-1 R5 Envs supported fusion mediated by SIV mac239, mac316, or mac316mut Env (24) (data not shown). To confirm these findings, we also performed virus infection experiments with luciferase reporter–HIV-1 R5 Env pseudoviruses with the D187A, N11A, and N11A D187A mutant CXCR4s. In general, we found results similar to those achieved with the cell-cell fusion assay; i.e., the combination mutant N11A D187A was better at supporting R5 Env-mediated fusion (as measured by virus entry) than was the N11A or D187A mutant alone with pseudoviruses composed of JR-FL, ADA, Ba-L, or SF162 (Fig. 6). We repeated this experiment numerous times, using several suitable target cell types, and achieved essentially the same results, with the relative light unit values being more than 1 log lower than those for CCR5 with the N11A D187A mutant and approximately 3 logs lower with the D187A mutant. Indeed, the single N11A mutant CXCR4, which weakly supports cell-cell fusion mediated by JR-FL Env, did not consistently support R5 Env pseudovirus entry. These HIV-1 pseudovirus infection results obtained with the D187A mutant are in contrast to recent results reported by Wang et al. (58), who found very substantial virus entry luciferase signals with a D187A mutant CXCR4 expressed in U87-MG cells. It is possible that the discrepancy between the results obtained with our two types of assays is the result of variations in the levels of CD4 and/or coreceptor expression in the two assays; vaccinia virus promoters were used to express CD4 and coreceptor in the cell-cell fusion assay, while CMV promoters were used in the virus infection assay. To address this possibility, we performed the cell-cell fusion assay with CMV promoter-driven coreceptor and CD4 expression. Although the β-Gal levels were much lower, reflecting the fact that the vaccinia virus expression system yields much higher gene expression levels, the results again showed that the N11A D187A CXCR4 mutant functioned nearly as well as CCR5 as a coreceptor for R5 Envs (Fig. 7). With regard to the minor discrepancy between our results, obtained with the D187A mutant and virus infection, and those of Wang et al. (58), it may be a cell type phenomenon in which the mutant CXCR4 is better recognized by R5 Envs in U87-MG cells; however, we think that this is unlikely since the U373-MG cells used in our assays are quite similar to those employed by Wang et al. Alternatively, this difference could reflect an as-yet-unidentified postbinding function of the coreceptor during virus infection.

FIG. 5.

Coreceptor function of mutant CXCR4s that support R5 Env fusion in a syncytium assay with the R5 isolate JR-FL Env. U373 target cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding wild-type CXCR4 or the indicated mutant CXCR4 construct linked to a vaccinia virus promoter and infected with vCB21R-LacZ and vCB-3 (CD4). (A) Wild-type CXCR4; (B) CXCR4 D187A; (C) CXCR4 N11A D187A; (D) wild-type CCR5. HeLa effector cells were infected with vaccinia virus encoding the JR-FL Env (vCB28). Duplicate cell mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 6 h. Fusion was assessed by light microscopy after staining cells with crystal violet. Magnification, ×200.

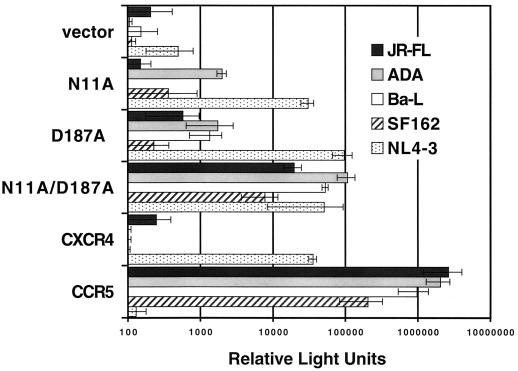

FIG. 6.

Coreceptor function of mutant CXCR4s in virus infection assays with R5 HIV-1 Envs. U373-CD4+ cells were transfected with a plasmid (pCDNA3) encoding the indicated wild-type coreceptor (CXCR4 or CCR5) or mutant CXCR4. Wells of cells (in triplicate) were infected with the indicated HIV-1 Env luciferase reporter virus. Infection was assessed on day 4 by measuring the amounts of luciferase activity in cell lysates. The luciferase activities shown were obtained from separate samples in the same experiment. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of the mean values for triplicate wells. This experiment was performed three times, and the data from one experiment are shown in the figure.

FIG. 7.

Coreceptor function of mutant CXCR4s in cell-cell fusion assays with low-level expression. U373-CD4+ cells were transfected with a plasmid (pCDNA3) encoding the indicated wild-type coreceptor (CXCR4 or CCR5) or mutant CXCR4, and after overnight expression the cells were infected with vCB21R-LacZ. HIV-1 effector cells were infected with vTF1.1 (T7 polymerase) and vaccinia virus encoding either the JR-FL Env (vCB28) or the IIIB/BH10 Env (vCB40). Fusion was assessed by measurement of β-Gal in detergent lysates of cells. Error bars represent the standard deviations for duplicate fusion assays. OD, optical density.

Roles of extracellular cysteines.

The cysteine residues in ecl-1 and ecl-2 are highly conserved among the 7TMGPCRs and are believed to form a disulfide bond between each other (54). Our findings support the hypothesis that this pair of cysteines in CXCR4 forms a disulfide bond and is probably critical for proper folding and cell surface expression. Both the C109A and C186A individual CXCR4 mutants were essentially undetectable on the cell surface upon expression (Table 2). Substituting alanine for either of these cysteines, individually, abrogates cell surface expression, as determined by cell surface antibody staining with 12G5, a conformation-dependent anti-CXCR4 MAb, and 4G10, a conformation-independent anti-CXCR4 MAb. Interestingly, replacing both cysteines (C109A C186A) with alanine allowed for a small amount of surface expression (about 10% of the wild-type level [Table 2]). This might be accounted for by the possibility that a single cysteine elimination allows for inappropriate disulfide bond formation among the remaining three extracellular cysteines. The inappropriate disulfide bond formation may result in misfolded CXCR4 molecules that are not well expressed on the cell surface.

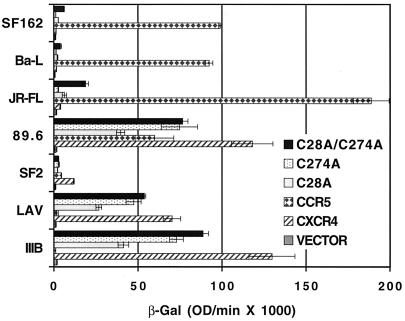

Examination of the second cysteine pair provided more interesting results. This second pair of extracellular cysteine residues, one in the N terminus and another in ecl-3, is conserved among the chemokine receptors but not by other 7TMGPCR family members. Our results indicate that these cysteines may also form a disulfide bond but that this bond is not essential for coreceptor function for HIV-1 Env-mediated membrane fusion. Replacement of the N-terminal cysteine alone (C28A) resulted in a greater than 50% reduction in coreceptor activity with several X4 or R5X4 Envs, while substitution of alanine for the ecl-3 cysteine or for both the N-terminal and ecl-3 cysteines yielded a CXCR4 molecule possessing near 75% of the wild-type level of activity (Fig. 8). If there were not a bond between these two cysteines, one would expect the double cysteine mutant to have no more activity than either of the single cysteine mutants. While the single and double cysteine mutants are expressed at wild-type levels, as determined by fluorescence-activated flow cytometry analysis with 4G10 (a conformation-independent MAb), they all exhibited reduced staining with 12G5 (a conformation-dependent MAb) (Table 2), strongly suggesting that an alteration in conformation has occurred through elimination of this disulfide bond. As with the cysteines in ecl-1 and ecl-2, MAb 12G5 cell surface immunostaining indicated that concomitant replacement of both the N-terminus cysteine and the ecl-3 cysteine resulted in some restoration of the protein’s conformation, with higher surface expression levels than those attained with either cysteine mutation by itself. Because of this latter observation, we again speculate that mutation of a single cysteine allows its paired cysteine to form inappropriate disulfide linkages, to some extent, with the remaining cysteines in the molecule, resulting in protein misfolding.

FIG. 8.

Coreceptor function of cysteine mutant CXCR4s in cell-cell fusion assays with R5, X4, and R5X4 HIV-1 Envs. U373 target cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding the wild-type coreceptor (CXCR4 or CCR5) or mutant CXCR4 construct linked to a vaccinia virus promoter and infected with vCB21R-LacZ and vCB-3 (CD4). HeLa effector cells were infected with vTF1-1 (T7 polymerase) and either vCB-32 (SF162), vCB-43 (Ba-L), vCB-28 (JR-FL), vDC-1 (89.6), vCB-34 (SF2), vCB-41 (LAV), or vCB-40 (IIIB/BH10). Fusion was assessed by measurement of β-Gal in detergent lysates of cells. The rates of β-Gal activity shown were obtained from separate samples in the same experiment. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of the mean values obtained for duplicate fusion assays. This experiment was performed three times, and the data from a representative experiment are shown in the figure. OD, optical density.

Finally, in addition to reducing the coreceptor activity of CXCR4 for R5X4 and X4 Envs, the N-terminal cysteine replacement (C28A) allowed CXCR4 to serve, albeit weakly, as a coreceptor for R5 isolate Envs (Fig. 8). Although replacement of the ecl-3 cysteine (C274A) did not result in coreceptor activity for R5 isolate Envs, combining the C28A and the C274A substitutions resulted in much higher coreceptor activity for R5 isolate Envs than the single C28A substitution. Thus, replacement of the C28 C274 cysteine pair appears to have a less drastic effect on CXCR4 conformation than replacement of just one of these two cysteines, though the C28 C274 mutant is altered enough in some fashion to allow it to function as a coreceptor for R5 Envs.

DISCUSSION

The three-dimensional (3D) structures of the HIV-1 coreceptors are presently unknown. We have recently presented theoretical 3D models of the HIV-1 coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5 based on the physically determined structures of both bacteriorhodopsin and rhodopsin, as well as analysis of the amino acid sequences of related G-protein-coupled receptors (20, 22). Two notable features can be derived from these models. First, the proteins are barrel shaped, and there is a close positioning of the extracellular loops brought about by the two potential extracellular disulfide linkages. This helps explain the many observations, by a number of groups that have employed chimeric coreceptor constructs, which have indicated the involvement of multiple extracellular regions in coreceptor constructs, which have indicated the involvement of multiple extracellular regions in coreceptor function for CCR5 (4, 7, 25, 31, 34, 42, 49, 60) as well as CXCR4 (8, 34, 43). Second, the models highlight the differences in the electrostatic potentials of the extracellular portions of the molecules, which may be a key element in determining usage by a particular HIV-1 isolate. Since the identification of the coreceptors for HIV-1, we and others have proposed that individual HIV-1 Envs have binding preferences for a particular coreceptor, mediated perhaps through interaction with the V3 loop (11, 19). The CXCR4 surface indicates that there is a greater negative charge at the extracellular surface. In contrast, CCR5 is less negatively charged. The overall charge of the V3 loop (an important determinant of cell tropism) of the HIV-1 Env is positive, with an X4 Env V3 loop region being more positively charged than an R5 Env V3 loop sequence. This model correlates with the coreceptor type usage depending on the type of HIV-1 Env, and obviously this suggests a simple explanation for the preferential interaction of T-tropic X4 Envs with CXCR4. Indeed, recent studies have confirmed this notion by showing that specific amino acids in the V3 loop of Env can determine cellular tropism and regulate chemokine coreceptor preferences (52).

Our results with alanine substitutions for charged extracellular amino acids in CXCR4 indicate that the N terminus and ecl-1 and -2 are involved in coreceptor function for X4 and R5X4 Env-mediated fusion. Specifically, it was primarily negatively charged glutamic acid residues, E14, E15, and E32, in the N terminus and the aspartic acid residue D97 in ecl-1 which upon removal by alanine substitution resulted in a profound impairment of the protein’s coreceptor function, with inhibition values of greater than 50% compared to wild-type CXCR4 activity. Also, the glutamic acid residue mutation E32A in CXCR4 corresponds to the glutamic acid residue at position 18 in CCR5 that was also shown to be important for CCR5 coreceptor activity for an R5 and an R5X4 HIV-1 isolate (26). On the other hand, the elimination of the single positively charged residue in ecl-1 (K110A) was much less important for the majority of Envs examined (LAV, IIIB, and 89.6), although on average there was a consistent pattern of reduced coreceptor activity, to approximately 60 to 75% of the activity of wild-type CXCR4. The SF2 Env appeared unaffected by the ecl-1 mutations. These results suggest an important role for the N terminus and ecl-1 of CXCR4 in both X4 and R5X4 Env-mediated fusion, primarily through several negatively charged amino acid residues.

The replacement of the positively charged arginine residue in ecl-2 by alanine (R188A) was the only other charged amino acid alteration that resulted in significantly reduced coreceptor activity for all four Envs examined, and although other individual mutations in ecl-2 and ecl-3 revealed some less-potent inhibitory effects on coreceptor activity for LAV, IIIB, or 89.6, no consistent pattern was evident. One particular Env, SF2, also had a reduced ability to employ CXCR4 as a coreceptor when any of four other charged residues, E26, K25, D187, or D193, was converted to alanine, and this may reflect the notion that although some coreceptor residues or domains appear to be globally important, an individual Env can differentially interact with a particular coreceptor and harbor additional structural dependencies. Taken together, the SF2 Env appeared more dependent on ecl-2 than on ecl-1 in comparison to the other Envs examined. Finally, the single hydrophobic-residue substitution (F201A) appeared to negatively affect all Envs tested, and this mutation was expressed at a level nearly equivalent to that of wild-type CXCR4, as detected with the 12G5 MAb. In light of this observation, we may pursue an extended investigation of other extracellular hydrophobic residues in our system.

In general, our data fit with other reports indicating an importance of positively charged Env residues in the V3 loop region of the previously classified syncytium-inducing X4 Envs (18, 28) and more recent work indicating that a higher net negative charge in the V3 regions of four of five Envs examined correlated with an increase in CCR5 usage (52). It was unfortunate that a combination of the E14A and E31A N-terminal mutations resulted in severely impaired cell surface expression, and because of this result, we have not yet pursued any other additive combinations of the impairing mutations we have identified, though we may do so in future experiments. Future experiments may also focus on noncharged extracellular and/or transmembrane amino acids, since several nonpolar residues have been reported to play a role in the coreceptor activity of CCR5 (26, 47) and transmembrane residues are important for ligand binding to a number of 7TMGPCRs (53).

Our results with mutation of the cysteine residues in CXCR4 provide further information on the structure of CXCR4. These coreceptor activities in Env-mediated fusion and cell surface expression data support the notion that both pairs of extracellular cysteine residues are involved in disulfide bond formation. Whereas the cysteine pair in ecl-1 and ecl-2 appears to be critical for proper folding and surface expression, the cysteine pair in the N terminus and ecl-3 appeared less so in that cell surface expression at wild-type levels was detected with a conformation-independent anti-CXCR4 MAb. In addition, the surprising result that this cysteine pair (C28 C274), upon removal by alanine substitution, allowed for some support of R5 Env-mediated fusion suggests that the altered conformation is presenting sites of interaction on CXCR4 that are unavailable in the wild-type CXCR4 molecule.

The tropism-altering substitutions in CXCR4 that we found were quite surprising and have led us to hypothesize that although the primary sequences of the extracellular domains of CCR5 and CXCR4 are quite dissimilar, the molecules may be somewhat more similar in terms of a conformation-dependent binding site. The most potent single substitution we discovered was the elimination of the negatively charged aspartic acid residue 187 in ecl-2. We found that this single change had profound effects in that it allowed the CXCR4 protein to serve as a functional coreceptor for R5 HIV-1 Envs (13). We speculate that the removal of this key negatively charged residue in ecl-2 reduces the CXCR4 domain’s net negative charge, allowing for an appropriate region of an R5 Env, perhaps including the V3 loop, to associate with CXCR4’s extracellular surface, while an R5 Env is repelled when the aspartic acid residue is present at position 187. Similar results were recently reported by Wang et al. (58). However, among our CXCR4 mutations, we also discovered some other single-amino-acid mutations that had similar effects, the second most potent corresponding to the removal of the N-terminal potential glycosylation site (N11A). The combination of N11A and D187A mutations (the two most potent tropism-altering changes) had a better than additive effect and actually supported R5 Env-mediated cell-cell fusion and syncytium formation at levels similar to CCR5. We hypothesize that the absence of bulky (due to N-linked glycosylation) or charged (D187) groups in the tropism-altering CXCR4 mutants allows for interaction with R5 Envs. This interaction could be through CXCR4 extracellular elements of an underlying or conserved coreceptor structure that is common to both CXCR4 and CCR5. We are actively engaged in experiments designed to directly address the influences of the potential N-linked glycosylation sites in CXCR4 on coreceptor function. In addition, our observation that the C28A C274A mutant also allows for some recognition and use by R5 Envs also supports this notion. The removal of this disulfide bond between the N terminus and ecl-3 results in a conformational alteration in the molecule, as measured by the reactivity of MAb 12G5, yet the molecule is surface expressed at levels comparable to wild-type CXCR4 and supports X4 and R5X4 Env-mediated fusion at nearly wild-type CXCR4 levels. A possible explanation that fits with our other data is that without this linkage, the CXCR4 molecule is in a relaxed or more opened state and is repositioning the N-terminal glycosylation side group, thus allowing access for an R5 Env. The fusion signals generated with JR-FL Env-mediated fusion for the C28A C274A and N11A mutants are remarkably comparable, although they are biochemically very distinct.

Interestingly, the N11A D187A mutant CXCR4 also supported HIV-1 R5 Env-pseudotyped virus entry, but not to the extent of CCR5 as a coreceptor. None of the other mutant CXCR4s consistently supported infection with R5 Env-pseudotyped virus. Future experiments may address whether the discrepancy between fusion and infection data is due to postbinding effects of CCR5, which are not significant for a cell-cell fusion event but may be important for subsequent stages of viral infection. However, to date there is no evidence that the HIV-1 Env-mediated cell-cell fusion event is mechanistically different from the Env-mediated virus infection fusion event (for reviews, see references 20 and 35).

Finally, we did observe that upon highlighting many of the residues that influence coreceptor function for X4 or R5X4 Env usage (E14, E15, E32, D97, and K110) and that alter CXCR4 in a manner allowing R5 Env usage in our 3D model of CXCR4 (N11 and D187) (20, 22), a clustering of these residues on one face and side of the molecule’s extracellular region was revealed. It is intriguing to speculate that this clustering is highlighting a conformation-dependent binding face for Env. Presently, however, we cannot exclude the possibility that these CXCR4 mutations are adversely affecting a proper CXCR4-CD4 interaction, and we are investigating this possibility. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that CD4 and CXCR4 can be coimmunoprecipitated (33), and they have been shown to colocalize (56); also, these interactions can be markedly enhanced by the binding of HIV-1 gp120 (21). In addition, we have recently obtained evidence that the same coimmunoprecipitation and colocalization events exist for CD4 and CCR5 (22, 61).

In summary, the data presented here add some detail to our understanding of the critical extracellular domains of CXCR4 required for HIV-1 Env-mediated membrane fusion. We have provided evidence that several negatively charged residues in the N terminus and loops are important for optimal coreceptor activity, and this confirms prior observations that multiple extracellular domains of CXCR4 are involved in the Env-mediated membrane fusion process. A likely explanation for the functional roles of these residues is that they are involved directly in Env binding by serving as key residues in a 3D or conformation-dependent binding region. Alternatively, some of these residues may be required for preserving the native CXCR4 structure only and thus are indirectly required; however, all of the most-impaired mutant CXCR4s are recognized by the conformation-dependent 12G5 MAb. These data provide a framework for the delineation of the Env-CD4-coreceptor contact sites and will aid future studies toward an understanding of the complex membrane fusion process mediated by HIV-1 Env and its receptors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Joseph Isaac for viruses and cells. Plasmids for pseudo-HIV construction were generously provided by Robert Doms, University of Pennsylvania. A number of reagents were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH).

This study was supported by NIH grants R29AI414110 and R01AI43885 (to C.C.B.) and Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences grants RO73FG (to C.C.B.) and RO1AI37438 (to G.V.Q.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi A, Gendelman H E, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin M A. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol. 1986;59:284–291. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.284-291.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander W A, Moss B, Fuerst T R. Regulated expression of foreign genes in vaccinia virus under the control of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase and the Escherichia coli lac repressor. J Virol. 1992;66:2934–2942. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2934-2942.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkhatib G, Broder C C, Berger E A. Cell type-specific fusion cofactors determine human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tropism for T-cell lines versus primary macrophages. J Virol. 1996;70:5487–5494. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5487-5494.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atchison R E, Gosling J, Monteclaro F S, Franci C, Digilio L, Charo I F, Goldsmith M A. Multiple extracellular elements of CCR5 and HIV-1 entry: dissociation from response to chemokines. Science. 1996;274:1924–1926. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger E A, Doms R W, Fenyo E M, Korber B T, Littman D R, Moore J P, Sattentau Q J, Schuitemaker H, Sodroski J, Weiss R A. A new classification for HIV-1. Nature. 1998;391:240. doi: 10.1038/34571. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger E A, Nussbaum O, Broder C C. HIV envelope glycoprotein/CD4 interactions: studies using recombinant vaccinia virus vectors. In: Karn J, editor. HIV: a practical approach. Vol. 2. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bieniasz P D, Fridell R A, Aramori I, Ferguson S S, Caron M G, Cullen B R. HIV-1-induced cell fusion is mediated by multiple regions within both the viral envelope and the CCR-5 co-receptor. EMBO J. 1997;16:2599–2609. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brelot A, Heveker N, Pleskoff O, Sol N, Alizon M. Role of the first and third extracellular domains of CXCR-4 in human immunodeficiency virus coreceptor activity. J Virol. 1997;71:4744–4751. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4744-4751.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broder C C, Berger E A. Fusogenic selectivity of the envelope glycoprotein is a major determinant of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tropism for CD4+ T-cell lines vs. primary macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9004–9008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.9004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broder C C, Collman R G. The chemokine receptors and HIV. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:20–29. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broder C C, Dimitrov D S. HIV and the 7-transmembrane domain receptors. Pathobiology. 1996;64:171–179. doi: 10.1159/000164032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broder C C, Dimitrov D S, Blumenthal R, Berger E A. The block to HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein-mediated membrane fusion in animal cells expressing human CD4 can be overcome by a human cell component(s) Virology. 1993;193:483–491. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chabot D J, Broder C C. Keystone Symposia: HIV pathogenesis and treatment. Silverthorne, Colo: Keystone Symposia; 1998. Alanine scanning mutagenesis of the extracellular domains of CXCR4, abstr. 3015; p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chakrabarti, S., and B. Moss. Unpublished data.

- 15.Cheng-Mayer C, Quiroga M, Tung J W, Dina D, Levy J A. Viral determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 T-cell or macrophage tropism, cytopathogenicity, and CD4 antigen modulation. J Virol. 1990;64:4390–4398. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4390-4398.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collman R, Balliet J W, Gregory S A, Friedman H, Kolson D L, Nathanson N, Srinivasan A. An infectious molecular clone of an unusual macrophage-tropic and highly cytopathic strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1992;66:7517–7521. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7517-7521.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connor R I, Chen B K, Choe S, Landau N R. Vpr is required for efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in mononuclear phagocytes. Virology. 1995;206:935–944. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Jong J-J, De Ronde A, Keulen W, Tersmette M, Goudsmit J. Minimal requirements for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 V3 domain to support the syncytium-inducing phenotype: analysis by single amino acid substitution. J Virol. 1992;66:6777–6780. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6777-6780.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dimitrov D S. Fusin—a place for HIV-1 and T4 cells to meet. Nat Med. 1996;2:640–641. doi: 10.1038/nm0696-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dimitrov D S, Broder C C. HIV and membrane receptors. Austin, Tex: Landes Bioscience; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimitrov D S, Norwood D, Stantchev T S, Feng Y, Xiao X, Broder C C. A mechanism of resistance to HIV-1 entry: inefficient interactions of CXCR4 with CD4 and gp120 in macrophages. Virology. 1999;259:1–6. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimitrov D S, Xiao X, Chabot D J, Broder C C. HIV coreceptors. J Membr Biol. 1998;166:75–90. doi: 10.1007/s002329900450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doms R W, Moore J P. HIV-1 coreceptor use: a molecular window into viral tropism, p. III-1–III-12. In: Korber B, Foley B, Leitner T, McCutchan F, Hahn B, Mellors J W, Myers G, Kuilen C, editors. Human retroviruses and AIDS. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edinger A L, Amedee A, Miller K, Doranz B J, Endres M, Sharron M, Samson M, Lu Z H, Clements J E, Murphey-Corb M, Peiper S C, Parmentier M, Broder C C, Doms R W. Differential utilization of CCR5 by macrophage and T cell tropic simian immunodeficiency virus strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4005–4010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farzan M, Choe H, Martin K A, Sun Y, Sidelko M, Mackay C R, Gerard N P, Sodroski J, Gerard C. HIV-1 entry and macrophage inflammatory protein-1β-mediated signaling are independent functions of the chemokine receptor CCR5. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6854–6857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.6854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farzan M, Choe H, Vaca L, Martin K, Sun Y, Desjardins E, Ruffing N, Wu L, Wyatt R, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. A tyrosine-rich region in the N terminus of CCR5 is important for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry and mediates an association between gp120 and CCR5. J Virol. 1998;72:1160–1164. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1160-1164.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng Y, Broder C C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fouchier R A, Groenink M, Kootstra N A, Tersmette M, Huisman H G, Miedema F, Schuitemaker H. Phenotype-associated sequence variation in the third variable domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 molecule. J Virol. 1992;66:3183–3187. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.3183-3187.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibbs C S, Zoller M J. Identification of electrostatic interactions that determine the phosphorylation site specificity of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5329–5334. doi: 10.1021/bi00236a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrington R D, Geballe A P. Cofactor requirement for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry into a CD4-expressing human cell line. J Virol. 1993;67:5939–5947. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.5939-5947.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hill C M, Kwon D, Jones M, Davis C B, Marmon S, Daugherty B L, DeMartino J A, Springer M S, Unutmaz D, Littman D R. The amino terminus of human CCR5 is required for its function as a receptor for diverse human and simian immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoproteins. Virology. 1998;248:357–371. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang S S, Boyle T J, Lyerly H K, Cullen B R. Identification of the envelope V3 loop as the primary determinant of cell tropism in HIV-1. Science. 1991;253:71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1905842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lapham C K, Ouyang J, Chandrasekhar B, Nguyen N Y, Dimitrov D S, Golding H. Evidence for cell-surface association between fusin and the CD4-gp120 complex in human cell lines. Science. 1996;274:602–605. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu Z, Berson J F, Chen Y, Turner J D, Zhang T, Sharron M, Jenks M H, Wang Z, Kim J, Rucker J, Hoxie J A, Peiper S C, Doms R W. Evolution of HIV-1 coreceptor usage through interactions with distinct CCR5 and CXCR4 domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6426–6431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore J, Jameson B, Weiss R, Sattentau Q. The HIV-cell fusion reaction. In: Bentz J, editor. Viral fusion mechanisms. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1993. pp. 233–289. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore J P, Trkola A, Dragic T. Co-receptors for HIV-1 entry. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:551–562. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moriuchi M, Moriuchi H, Turner W, Fauci A S. Exposure to bacterial products renders macrophages highly susceptible to T-tropic HIV-1. J Clin Investig. 1998;102:1540–1550. doi: 10.1172/JCI4151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munoz-Barroso I, Durell S, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Blumenthal R. Dilation of the human immunodeficiency virus-1 envelope glycoprotein fusion pore revealed by the inhibitory action of a synthetic peptide from gp41. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:315–323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nussbaum O, Broder C C, Berger E A. Fusogenic mechanisms of enveloped-virus glycoproteins analyzed by a novel recombinant vaccinia virus-based assay quantitating cell fusion-dependent reporter gene activation. J Virol. 1994;68:5411–5422. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5411-5422.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Brien W A, Koyanagi Y, Namazie A, Zhao J Q, Diagne A, Idler K, Zack J A, Chen I S Y. HIV-1 tropism for mononuclear phagocytes can be determined by regions of gp120 outside the CD4-binding domain. Nature. 1990;348:69–73. doi: 10.1038/348069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Page K A, Landau N R, Littman D R. Construction and use of a human immunodeficiency virus vector for analysis of virus infectivity. J Virol. 1990;64:5270–5276. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5270-5276.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Picard L, Simmons G, Power C A, Meyer A, Weiss R A, Clapham P R. Multiple extracellular domains of CCR-5 contribute to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry and fusion. J Virol. 1997;71:5003–5011. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5003-5011.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Picard L, Wilkinson D, McKnight A, Gray P, Hoxie J, Clapham P, Weiss R. Role of the amino-terminal extracellular domain of CXCR-4 in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry. Virology. 1997;231:105–111. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Planelles V, Li Q-X, Chen I S Y. The biological and molecular basis for cell tropism in HIV. In: Cullen B R, editor. Human retroviruses. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 17–48. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Premack B A, Schall T J. Chemokine receptors: gateways to inflammation and infection. Nat Med. 1996;2:1174–1178. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quinnan G V, Jr, Zhang P F, Fu D W, Dong M, Margolick J B. Evolution of neutralizing antibody response against HIV type 1 virions and pseudovirions in multicenter AIDS cohort study participants. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:939–949. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rabut G E, Konner J A, Kajumo F, Moore J P, Dragic T. Alanine substitutions of polar and nonpolar residues in the amino-terminal domain of CCR5 differently impair entry of macrophage- and dualtropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:3464–3468. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3464-3468.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ratner L, Fisher A, Jagodzinski L L, Mitsuya H, Liou R S, Gallo R C, Wong-Staal F. Complete nucleotide sequences of functional clones of the AIDS virus. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1987;3:57–69. doi: 10.1089/aid.1987.3.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rucker J, Samson M, Doranz B J, Libert F, Berson J F, Broder C C, Vassart G, Doms R W, Parmentier M. Regions in β-chemokine receptors CCR-5 and CCR-2b that determine HIV-1 cofactor specificity. Cell. 1996;87:437–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidtmayerova H, Alfano M, Nuovo G, Bukrinsky M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 T-lymphotropic strains enter macrophages via a CD4- and CXCR4-mediated pathway: replication is restricted at a postentry level. J Virol. 1998;72:4633–4642. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4633-4642.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simmons G, Reeves J D, McKnight A, Dejucq N, Hibbitts S, Power C A, Aarons E, Schols D, De Clercq E, Proudfoot A E, Clapham P R. CXCR4 as a functional coreceptor for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of primary macrophages. J Virol. 1998;72:8453–8457. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8453-8457.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Speck R F, Wehrly K, Platt E J, Atchison R E, Charo I F, Kabat D, Chesebro B, Goldsmith M A. Selective employment of chemokine receptors as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptors determined by individual amino acids within the envelope V3 loop. J Virol. 1997;71:7136–7139. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.7136-7139.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strader C D, Fong T M, Graziano M P, Tota M R. The family of G-protein-coupled receptors. FASEB J. 1995;9:745–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strader C D, Fong T M, Tota M R, Underwood D, Dixon R A. Structure and function of G protein-coupled receptors. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:101–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trkola A, Dragic T, Arthos J, Binley J M, Olson W C, Allaway G P, Cheng-Mayer C, Robinson J, Maddon P J, Moore J P. CD4-dependent, antibody-sensitive interactions between HIV-1 and its coreceptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:184–187. doi: 10.1038/384184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ugolini S, Moulard M, Mondor I, Barois N, Demandolx D, Hoxie J, Brelot A, Alizon M, Davoust J, Sattentau Q J. HIV-1 gp120 induces an association between CD4 and the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J Immunol. 1997;159:3000–3008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verani A, Pesenti E, Polo S, Tresoldi E, Scarlatti G, Lusso P, Siccardi A G, Vercelli D. CXCR4 is a functional coreceptor for infection of human macrophages by CXCR4-dependent primary HIV-1 isolates. J Immunol. 1998;161:2084–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Z X, Berson J F, Zhang T Y, Chen Y H, Sun Y, Sharron M, Lu Z H, Peiper S C. CXCR4 sequences involved in coreceptor determination of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 tropism. Unmasking of activity with M-tropic Env glycoproteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15007–15015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu L, Gerard N P, Wyatt R, Choe H, Parolin C, Ruffing N, Borsetti A, Cardoso A A, Desjardin E, Newman W, Gerard C, Sodroski J. CD4-induced interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins with the chemokine receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:179–183. doi: 10.1038/384179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu L, LaRosa G, Kassam N, Gordon C J, Heath H, Ruffing N, Chen H, Humblias J, Samson M, Parmentier M, Moore J P, Mackay C R. Interaction of chemokine receptor CCR5 with its ligands: multiple domains for HIV-1 gp120 binding and a single domain for chemokine binding. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1373–1381. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiao X, Wu L, Feng Y-R, Ugolini S, Chabot D, Shen Z, Broder C C, Sattentau Q J, Dimitrov D S. Constitutive cell surface association between CD4 with CCR5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7496–7501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yi Y, Rana S, Turner J D, Gaddis N, Collman R G. CXCR-4 is expressed by primary macrophages and supports CCR5-independent infection by dual-tropic but not T-tropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:772–777. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.772-777.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]