When four psychiatrists published a study showing that six out of 23 schizophrenic patients carried weapons during psychotic episodes, little did they realise how their work would be presented to the public. The day after it appeared in the Royal College of Psychiatrists' Bulletin in 1998, banner headlines in the Sunday Express proclaimed: “Armed and dangerous: public at risk as mental patients escape the care net.” The Sunday Express journalist extrapolated that 1250 mentally ill patients in the community carried weapons and posed “a serious threat to public safety.” This claim was based on a figure quoted by the Zito Trust that 5000 schizophrenic patients in the community represented a danger to themselves or others.

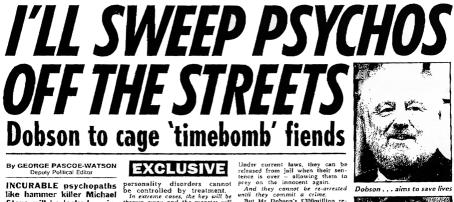

Distortions of this kind are no surprise to mental health groups. Focus on Mental Health, an umbrella organisation, thinks that mentally ill people get a raw deal from the press, with words such as “maniac,” “schizo,” and “psycho” contributing to the stigma. Consequently, a year ago, it joined with the National Union of Journalists, the Department of Health, and Lilly Psychiatry to set up the Media Forum on Mental Health to fight inaccurate and unbalanced media coverage.

The mental health charity Mind is also trying to fight unfair reporting. It recently conducted a survey of more than 500 people within Mind's user networks to discover what impact media coverage of mental health issues had on their lives. Almost three quarters of respondents thought that media coverage had been unfair, unbalanced, or very negative. Moreover, half said that this media coverage had had a negative effect on their mental health, with a third feeling more anxious or depressed as a result and 22% feeling more withdrawn. Respondents voted the Sun as the newspaper with the worst coverage of mental health issues.

Journalists and mental health activists met at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, under the auspices of the Media Forum on Mental Health, last week to discuss this issue. In the “irresponsible media” corner were representatives from Carlton Television, Thames Radio, and the BBC, and journalists from the regional, national, and specialist press. The Sun, Mirror and Daily Sport were notable by their absence. In the “responsible, mental health service users and workers” corner were representatives from Mind, the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, the Manic Depression Fellowship, the National Schizophrenia Fellowship, and others. Health minister John Hutton also participated, and broadcaster Brian Hayes refereed the debate.

The main complaint from the mental health campaigners was that the media presented mentally ill people as dangerous time bombs waiting to explode, when the reality was quite different. They pointed out that 95% of homicides were committed by people with no mental illness and that mentally ill people were far more likely to harm themselves than others. Sue Baker, head of media relations at Mind, said: “Research published in January 1999 in the British Journal of Psychiatry showed that the proportion of homicides committed by people with mental illness has gone down by 3% a year since 1957. Yet this research was ignored by almost all the newspapers, with the exception of the Guardian.”

One member of the audience pointed out that whenever an airplane crashed, killing everyone on board, a spokesman for the airline immediately appeared on the media saying how safe it was to fly and how exceptional were such accidents. But if a mentally ill person killed a member of the public there was no organisation whose job was to appear on television and explain how rare an occurrence that was too.

While media representatives did not attempt to justify the use of such words as “psychos” and “nutters” in media stories, they did try to explain why newspapers often gave massive coverage to instances when “care in the community” seemed to go wrong. Steve Hewlett, director of programmes at Carlton Television, explained that newspapers often made substantial mileage out of mental health incidents, such as the murder of Jonathan Zito by Christopher Clunis, because they knew it awakened fear in their readers. “It is always easier to reinforce your readers' views than challenge them,” he said. “Newspaper editors are always trying to connect with their readers by showing that they understand them. It is easy for them to say: ‘We understand your fears, we know that there are nutters with machetes out there. We are here to campaign to change things for your sake.’”

He suggested that the mental health service users and workers in the audience could adopt one of two approaches to change things. They could either try to appeal to newspaper editors' better sides, which was difficult and often not productive, or they could make sure that whenever a sensationalist mental health story was published, that they went through it carefully, picking out mistakes and reporting them either to the Press Complaints Commission or the Broadcasting Standards Authority. “The really trenchant, well thought out, well reasoned attack will get a response, if only from a newspaper or television company's competitor,” Mr Hewlett added.

The debate saw little blood spilt. There were no knockout blows, mainly because the Mike Tysons of the media world—the Sun, Mirror, and News of the World—were not there. To see what the Sun thought about being named as the newspaper with the worst coverage of mental health issues, I telephoned David Yelland, the Sun's editor, for a comment. His secretary said that she would see if he had anything to say. She never rang back.