Abstract

Background:

Given the synergistic relationship between human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human papillomavirus (HPV) infections, knowledge of the genotypic prevalence and associated factors of high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) among HIV-infected women is crucial for developing targeted interventions such as appropriate screening tests and effective genotype-specific vaccination.

Objectives:

We determined the prevalence of any HR-HPV and multiple HR-HPV infections and identified associated factors among a cohort of women living with HIV infections (WLHIV) in Lagos, Nigeria.

Methods:

This descriptive cross-sectional study analysed the data of 516 WLHIV who underwent cervical cancer screening as part of the COMPASS-DUST study at the HIV treatment centre of Lagos University Teaching Hospital from July 2023 to March 2024. Multivariable binary logistic regression models were performed to explore factors associated with HR-HPV and multiple HR-HPV infections.

Results:

Among the 516 WLHIV enrolled (mean age, 46.5±7.3 years), the overall HR-HPV prevalence was 13.4% (95% CI, 10.6–16.6), disaggregated as 3.3% for HPV16/18 (95% CI, 1.9–5.2) and 11.6% for other HR-HPV genotypes (95% CI, 9.0–14.7). Nineteen women (3.7%; 95% CI, 2.2–5.7)had multiple HR-HPV genotype infections. Having a recent serum CD4+ cell count ≤560 cells/μL (adjusted OR 3.32; 95% CI 1.06–10.38) and HPV 16/18 genotype infections (adjusted OR 38.98; 95% CI 11.93–127.37) were independently associated with an increased risk of multiple HR-HPV infections.

Conclusion:

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the epidemiology of HR-HPV infections and highlight the need for tailored interventions and continuous monitoring. By addressing these challenges through targeted screening, effective ART management, and vaccination programs, we can improve health outcomes and reduce the burden of cervical cancer in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, HPV genotypes, Lagos, Multiple HPV infections, Screenings

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is a major global health concern, particularly due to its established role in the development of invasive cervical cancer [1]. Cervical cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality among women worldwide [2], with a disproportionately higher burden in low- and middle-income countries, including Nigeria, where screening and vaccination programs are less accessible [3].

Increasing evidence revealed a higher risk and poorer prognosis of cervical cancer among women with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) compared to the general population. HIV infection exacerbates the risk of acquiring high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) infections due to the immunocompromised state it induces [4]. Therefore, due to impaired immune function, there is an increased susceptibility to persistent HR-HPV infection due to ineffective viral clearance in HIV-infected individuals [5–8] that leads to the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia which can progress to invasive cervical cancer, if left untreated [4, 9, 10].

Given this synergistic relationship between HIV and HPV infections, knowledge of the genotypic prevalence and associated factors of HR-HPV among HIV-infected women is crucial for developing targeted interventions such as effective genotype-specific vaccination and appropriate cervical cancer screening tests. Nigeria, the most populous country in Africa, faces significant public health challenges related to both HIV and cervical cancer [6, 11]. Lagos, the most populous state and commercial capital of Nigeria presents a microcosm of these challenges, with a high burden of HIV infection and limited resources for comprehensive cervical cancer screening and prevention [10, 12]. Despite the significant risk of HR-HPV infection, data on its prevalence among women living with HIV (WLHIV) in Lagos is sparse [12, 13], thus limiting the ability to effectively design interventions to address this dual burden risk factor of cervical cancer. This study, therefore, aimed to fill this knowledge gap by determining the prevalence of any HR-HPV and multiple HR-HPV infections and identifying associated factors among WLHIV in Lagos, Nigeria. By elucidating these factors, we hope to inform public health strategies and clinical practices that can mitigate the impact of HR-HPV and improve health outcomes for this vulnerable population.

Participants and Methods

Study design and settings

This is a descriptive cross-sectional analysis of the data of WLHIV who underwent cervical cancer screenings as part of the baseline assessments in the “COMPASS-DUST” study. “COMPASS-DUST” is a two-phase study currently ongoing in the HIV treatment centre of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH). Details of the study design and procedure are published elsewhere [14]. LUTH, the leading public health institution in Lagos State, Southwest Nigeria, serves a population of over 20 million. It primarily functions as a referral centre for various government and private hospitals within Lagos and its neighbouring states. Each month, the LUTH HIV treatment clinic delivers comprehensive care to approximately 9,000 individuals living with HIV in Lagos and the surrounding states of Southwest Nigeria. The clinic also offers integrated reproductive health care to sexually active women with HIV infection such as routine cervical cancer screening with either a Pap smear, HPV DNA testing or visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) [10].

Eligibility criteria

We included and analyzed the data of n = 516 sexually active WLHIV aged 25–65 years who had their HR-HPV infection status recorded after undergoing pelvic examination and cervical liquid-based cytology (LBC) sample collection for cervical cancer screenings including Pap smear, p16/Ki-67 dual staining and HPV testing, at enrolment in the primary study [15] between July 2023 to March 2024. An HPV testing was conducted by a study pathologist/technician, utilizing HPV DNA target amplification by Polymerase Chain Reaction followed by nucleic acid hybridization to detect 14 high-risk HPV genotypes (types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68) in the LBC samples. Excluded from the study were women with suspicious cervical lesions; those with ongoing or recent pregnancy, those with previous HPV vaccination, those with a prior history of cervical cancer or who have had therapy for benign or malignant cervical lesions, and those who have had hysterectomy.

Extracted variables of interest

Variables extracted for analyses in the dataset included the participant’s age in years, number of previous childbirths and vaginal births, body mass index (BMI) in kg/m2, marital, educational and employment status, CD4 + cell count and viral load, age at menarche, coitarche and first pregnancy, menstrual status, use of oral hormonal contraceptive, number of lifetime sex partners, previous sexually transmitted infection (STI) treatment, and history of consumption of alcoholic beverages. BMI was calculated as the participant’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters [16].

Operational definitions of study outcomes

We assessed four study outcomes: the prevalence of any HR-HPV and multiple HR-HPV infections defined as the proportion of study participants with at least one HR-HPV genotype infection and more than one HR-HPV genotype infections, respectively; and associated factors of HR-HPV and multiple HR-HPV infections, which are variables collected at baseline in the COMPASS-DUST study [15] that were significantly associated with HR-HPV and multiple HR-HPV infections, respectively.

Sample size estimation

Using Fisher’s formula [17], we estimated a post-hoc sample size of n = 322 to assess the prevalence of HR-HPV infections and multiple HR-HPV infections in WLHIV based on a type I error rate of 5% at a 95% confidence level of 1.96 and a derived proportion of 24.5% for HR-HPV and 8.2% for multiple HR-HPV infections from an earlier study by Ezechi et al. [12], assuming a missing outcome data or data recording error rate of 5%. We, therefore, included the 516 WLHIV who had their HPV infection status recorded in the primary study [14] in our data analyses.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with Lilliefors’ significance correction and descriptive statistics were then computed for the participants’ baseline characteristics. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables were displayed as mean (± standard deviation). We estimated prevalence at 95% confidence intervals using the Clopper-Pearson exact test. Bivariable and multivariable binary logistic regression models were developed to identify variables associated with any HR-HPV and multiple HR-HPV infections. Age and other variables related to the study outcomes (P < 0.20) in the bivariable analyses were then included in the pool of variables for the multivariable analyses using the backward stepwise approach. An Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) was calculated continuously, and the final model step with the lowest AIC was chosen as the best-fit model. Associations in the final model were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Results

A total of n=516 HIV-infected women enrolled at baseline in the primary study [15] were included in the data analyses. Out of these enrolled women (mean age, 46.5±7.3 years), n=69 (13.4%; 95% CI, 10.6–16.6) had any HR-HPV infections disaggregated as 3.3% for HPV16/18 (95% CI, 1.9–5.2) and 11.6% for other HR-HPV genotypes (95% CI, 9.0–14.7). Nineteen women (3.7%; 95% CI, 2.2–5.7) had multiple HR-HPV genotype infections. The five most common HR-HPV genotypes were HPV 16 (20.0%), HPV 52 (17.2%), HPV 31 (12.8%), HPV 58 (11.4%), and HPV 51 (10.0%). The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the enrolled women are presented in Table 1.

Table 1:

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the HIV-infected women participants (n=516)

| Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Mean age at enrolment (± SD) in years | 46.5 ± 7.3 |

| Mean BMI (± SD) in kg/m 2 | 26.9 ± 15.3 |

| Mean CD4+ cell count (IQR) in cells/μL | 558.6 ± 172.2 |

| Mean age at menarche (± SD) in years | 15.2 ± 3.5 |

| Mean age at coitarche (± SD) in years | 19.9 ± 3.5 |

| Mean age at first pregnancy (± SD) in years | 23.4 ± 7.5 |

| Menstrual status | |

| Premenopausal | 308 (59.7) |

| Postmenopausal | 208 (40.3) |

| Parity | |

| Nulliparous | 26 (5.0) |

| Parous | 490 (95.0) |

| Previous vaginal birth | |

| Yes | 393 (76.2) |

| No | 123 (23.8) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 49 (9.5) |

| Married | 415 (80.4) |

| Separated | 7 (1.4) |

| Divorced | 9 (1.7) |

| Widowed | 36 (7.0) |

| Educational status | |

| Uneducated | 10 (1.9) |

| Primary education | 58 (11.2) |

| Secondary education | 269 (52.1) |

| Tertiary education | 162 (31.4) |

| Postgraduate education | 17 (3.3) |

| Employment status | |

| Unemployed | 9 (1.7) |

| Housewife | 16 (3.1) |

| Artisan | 9 (1.7) |

| Trading | 333 (64.5) |

| Privately/self employed | 84 (16.3) |

| Civil servant | 65 (12.6) |

| Use of oral contraceptive | |

| Yes | 68 (13.2) |

| No | 448 (86.8) |

| Number of lifetime sexual partners | |

| One | 189 (36.6) |

| More than one | 327 (63.4) |

| Previous STI | |

| Yes | 106 (20.5) |

| No | 410 (79.5) |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| Yes | 99 (19.2) |

| No | 417 (80.8) |

| HR-HPV infections | |

| Positive | 69 (13.4) |

| Negative | 447 (86.6) |

| Multiple HR-HPV infections | |

| Yes | 19 (3.7) |

| No | 497 (96.3) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HR-HPV, high-risk human papillomavirus; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; STI, sexually transmitted infections.

Values are given as mean ± SD, median (interquartile range), or frequency (percentage) unless indicated otherwise.

In the bivariable analyses, variables significantly associated with HR-HPV infections based on P<0.20 were recent CD4+ cell count ≤560 cells/μL, first pregnancy before age 23 years, nulliparity, being economically unengaged, and having previous treatment for sexually transmitted infections. However, following a multivariable analysis, none of these variables were independently associated with HR-HPV infections in WLHIV [Table 2].

Table 2:

Bivariable and multivariable analyses of factors associated with high-risk human papillomavirus infections

| Factor | HR-HPV Infections | Bivariate p -value | OR (95% CI) | Multivariable p -value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (%) | Negative (%) | ||||

| Number of participants | 69 (13.4) | 447 (86.6) | NA | NA | NA |

| Participants age | |||||

| ≥47 years | 36 (14.3) | 216 (85.7) | 0.551 | 1.29 (0.75–2.21) | 0.352 |

| <47 years | 33 (12.5) | 231 (87.5) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| BMI | |||||

| ≥27 kg/m 2 | 40 (14.8) | 231 (85.2) | 0.330 | NA | NA |

| <27 kg/m 2 | 29 (11.8) | 216 (88.2) | |||

| Recent CD4+ cell count | |||||

| ≤560 cells/μL | 40 (15.6) | 217 (84.4) | 0.145 | 1.33 (0.78–2.28) | 0.300 |

| >560 cells/μL | 29 (11.2) | 230 (88.8) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Age at menarche | |||||

| ≥15 years | 35 (12.5) | 246 (87.5) | 0.504 | NA | NA |

| <15 years | 34 (14.5) | 201 (85.5) | |||

| Age at coitarche | |||||

| <20 years | 34 (14.7) | 198 (85.3) | 0.439 | NA | NA |

| ≥20 years | 35 (12.3) | 249 (87.7) | |||

| Age at first pregnancy | |||||

| <23 years | 37 (17.1) | 180 (82.9) | 0.036 | 1.64 (0.98–2.74) | 0.060 |

| ≥23 years | 32 (10.7) | 267 (89.3) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Menstrual status | |||||

| Postmenopausal | 31 (14.9) | 177 (85.1) | 0.430 | NA | NA |

| Premenopausal | 38 (12.3) | 270 (87.7) | |||

| Parity | |||||

| Parous | 63 (12.9) | 427 (87.1) | 0.136 | 0.72 (0.26–1.98) | 0.524 |

| Nulliparous | 6 (23.1) | 20 (76.9) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Previous vaginal birth | |||||

| Yes | 53 (13.5) | 340 (86.5) | 0.892 | NA | NA |

| No | 16 (13.0) | 107 (87.0) | |||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 53 (12.8) | 362 (87.2) | 0.416 | NA | NA |

| Unmarried | 16 (15.8) | 85 (84.2) | |||

| Educational status | |||||

| Less than tertiary education | 46 (13.6) | 291 (86.4) | 0.799 | NA | NA |

| At least tertiary education | 23 (12.8) | 156 (87.2) | |||

| Employment status | |||||

| Economically unengaged | 7 (28.0) | 18 (72.0) | 0.028 | 2.43 (0.96–6.10) | 0.060 |

| Economically engaged | 62 (12.6) | 429 (87.4) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Use of oral contraceptive | |||||

| Yes | 11 (16.2) | 57 (83.8) | 0.466 | NA | NA |

| No | 58 (12.9) | 390 (87.1) | |||

| Lifetime sexual partners | |||||

| More than one | 48 (14.7) | 279 (85.3) | 0.251 | NA | NA |

| One | 21 (11.1) | 168 (88.9) | |||

| Previous STI | |||||

| Yes | 19 (17.9) | 87 (82.1) | 0.122 | 1.52 (0.85–2.72) | 0.161 |

| No | 50 (12.2) | 360 (87.8) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Alcohol consumption | |||||

| Yes | 13 (13.1) | 86 (86.9) | 0.938 | NA | NA |

| No | 56 (13.4) | 361 (86.6) | |||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; HR-HPV, high-risk human papillomavirus; NA, not applicable; OR, adjusted odds ratio; STI, sexually transmitted infections.

As shown in Table 3, participants aged ≥47 years, with recent serum CD4+ cell count ≤560 cells/μL, alcoholic beverage consumption, and having HPV 16/18 genotype infections were associated with multiple HR-HPV infections in the bivariable analyses. In the final multivariable analysis, having a recent serum CD4+ cell count ≤560 cells/μL (adjusted OR 3.32; 95% CI 1.06–10.38) and HPV 16/18 genotype infections (adjusted OR 38.98; 95% CI 11.93–127.37) were independently associated with multiple HR-HPV infections [Table 3].

Table 3:

Bivariable and multivariable analyses of factors associated with multiple high-risk human papillomavirus infections

| Variable | Multiple HR-HPV Infections | Bivariate p -value | OR (95% CI) | Multivariable p -value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | ||||

| Number of participants | 19 (3.7) | 497 (96.3) | NA | NA | NA |

| Participants age | |||||

| ≥47 years | 13 (5.2) | 239 (94.8) | 0.082 | 2.79 (0.91–8.54) | 0.072 |

| <47 years | 6 (2.3) | 258 (97.7) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| BMI | |||||

| ≥27 kg/m 2 | 10 (3.7) | 261 (96.3) | 0.992 | NA | NA |

| <27 kg/m 2 | 9 (3.7) | 236 (96.3) | |||

| Recent CD4+ cell count | |||||

| ≤560 cells/μL | 13 (5.1) | 244 (94.9) | 0.098 | 3.32 (1.06–10.38) | 0.039 |

| >560 cells/μL | 6 (2.3) | 253 (97.7) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Age at menarche | |||||

| ≥15 years | 11 (3.9) | 270 (96.1) | 0.759 | NA | NA |

| <15 years | 8 (3.4) | 227 (96.6) | |||

| Age at coitarche | |||||

| <20 years | 11 (4.7) | 221 (95.3) | 0.248 | NA | NA |

| ≥20 years | 8 (2.8) | 276 (97.2) | |||

| Age at first pregnancy | |||||

| <23 years | 10 (4.6) | 207 (95.4) | 0.341 | NA | NA |

| ≥23 years | 9 (3.0) | 267 (97.0) | |||

| Menstrual status | |||||

| Postmenopausal | 10 (4.8) | 198 (95.2) | 0.265 | NA | NA |

| Premenopausal | 9 (2.9) | 299 (97.1) | |||

| Parity | |||||

| Parous | 18 (3.7) | 472 (96.3) | 0.964 | NA | NA |

| Nulliparous | 1 (3.8) | 25 (96.2) | |||

| Previous vaginal birth | |||||

| Yes | 16 (4.1) | 377 (95.9) | 0.402 | NA | NA |

| No | 3 (2.4) | 120 (97.6) | |||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 17 (4.1) | 398 (95.9) | 0.311 | NA | NA |

| Unmarried | 2 (2.0) | 99 (98.0) | |||

| Educational status | |||||

| Less than tertiary education | 13 (3.9) | 324 (96.1) | 0.772 | NA | NA |

| At least tertiary education | 6 (3.4) | 173 (96.6) | |||

| Employment status | |||||

| Economically unengaged | 2 (8.0) | 23 (92.0) | 0.240* | NA | NA |

| Economically engaged | 17 (3.5) | 474 (96.5) | |||

| Use of oral contraceptive | |||||

| Yes | 2 (2.9) | 66 (97.1) | 0.728 | NA | NA |

| No | 17 (3.8) | 431 (96.2) | |||

| Lifetime sexual partners | |||||

| More than one | 13 (4.0) | 314 (96.8) | 0.642 | NA | NA |

| One | 6 (3.2) | 183 (96.8) | |||

| Previous STI | |||||

| Yes | 5 (4.7) | 101 (95.3) | 0.526 | NA | NA |

| No | 14 (3.4) | 396 (96.6) | |||

| Alcohol consumption | |||||

| Yes | 6 (6.1) | 93 (93.9) | 0.162 | 2.06 (0.65–10.38) | 0.221 |

| No | 513 (3.1) | 404 (96.9) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| HPV 16/18 genotype | |||||

| Yes | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) | <0.001 | 38.98 (11.93–127.37) | <0.001 |

| No | 11 (2.2) | 488 (97.8) | 1.00 | Reference | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; HR-HPV, high-risk human papillomavirus; NA, not applicable; OR, adjusted odds ratio; STI, sexually transmitted infections.

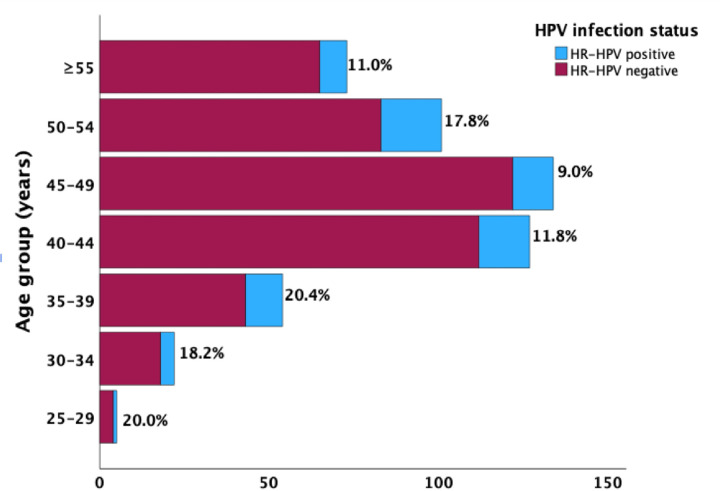

The age-specific prevalence rates of HR-HPV infections in WLHIV are shown in Figure 1. There was a trend towards a progressive decline in HR-HPV prevalence with age, with a bimodal peak prevalence seen in women aged 25–39 years (20.0–20.4%) and those in the 50–54 years age group (17.8%). The nadir prevalence was recorded in women aged 45–49 years (9.0%).

Figure 1.

Age-specific prevalence of HR-HPV infections in enrolled HIV-infected women.

Discussion

The findings from this descriptive cross-sectional study of HIV-infected women enrolled in the COMPASS-DUST study [14] provide significant insights into the prevalence and risk factors associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) infections in this vulnerable population. Our study reveals that one in seven of the participants have HR-HPV infections at baseline while the prevalence of multiple HR-HPV infections was considerably lower, with only one in 27 women affected. None of the baseline participants’ factors was associated with HR-HPV infections. However, having a serum CD4+ cell count below 560 cells/μL and a co-infection with either HPV 16 or 18 genotype were significantly associated with the detection of multiple HR-HPV infections.

The prevalence of HR-HPV infections (13.4%) recorded in our study aligns with existing literature across the world, suggesting that HIV-infected individuals have a high burden of HPV infections [8]. This figure is, however, lower than the prevalence of 24.5% reported by Ezechi et al. in 2014 [12] among a predominantly similar population of women in another clinical setting in Lagos, Nigeria, and even much lower than the 42.6% recorded in a recently published study by Traore et al. [18] in Bamako, Mali, and the reported pooled estimates of 64.0% by Menon et al. in 2016 [19] and 51.0% by Bogale et al. in 2020 [20] in two systematic reviews and meta-analyses among HIV infected women in Kenya and developing countries respectively. The higher prevalence rates in these studies may be influenced by regional variations in HPV epidemiology, variations in the diagnostic methods or sensitivity of HR-HPV detection techniques, temporal differences in the study periods reflecting changes in public health interventions or HIV care, and potential variations in implementation, adherence and efficacy of antiretroviral therapy (ART) across different settings. Notably, our study enrolled only sexually active women on ART with well-controlled HIV who are otherwise healthy, hence, the relatively lower HPV prevalence we recorded.

Our study revealed that 3.7% of the enrolled WLHIV had multiple HR-HPV genotype infections. This prevalence is notably close to the 8.2% reported in a 2014 study among HIV-positive women in a similar geographical setting in Lagos, Nigeria [12]. This is, however, at substantial variance from the broader Sub-Saharan Africa regional estimates of 22.6% prevalence reported in a 20-year systematic review of WLHIV [21]. These variations in study findings may be due to regional variations in HPV epidemiology, temporal differences in the study periods reflecting changes in public health interventions or HIV care, and the population characteristics as reflected in our study where only ART adherent and healthy HIV-infected women with well-controlled infections were enrolled.

Similar to the finding by Bogale et al. [20] in 2020, HPV 16 was the most prevalent HPV genotype (20.0%) in our study as reported in most of the existing literature [1,12]. This finding was, however, different from a previous review which reported HPV 52 as the most prevalent genotype (26.0%) among HIV-infected women [19]. HPV 52 (17.2%) is the second predominant HPV genotype observed in this current study. Our findings also underscore the predominant presence of HR-HPV types 16, 31, 51, 52, and 58, among which only HPV type 16 is covered by the currently approved and available vaccines (Cervarix and Gardasil) [22,23] adopted for the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi)-supported vaccine roll-out programs in Nigeria which started in October 2023 [24]. This further highlights the observations of several other studies reporting a high frequency of non-vaccine HPV types among WLHIV in Sub-Saharan Africa [21], thus, the need to reinforce the implementation of population-based HR-HPV screening programs as a crucial step in preventing cervical cancer among WLHIV across the Sub-Saharan Africa region. The age-specific prevalence rates of HR-HPV infections among WLHIV, as depicted in our study reveal a distinct trend of decreasing prevalence with increasing age [25–27]. The high prevalence seen in women aged 25–39 years is consistent with the epidemiological understanding of HR-HPV infections, where younger women tend to have higher prevalence rates due to factors such as higher rates of sexual activity, new sexual partnerships, and potentially less robust immune responses compared to older women [28] while the second peak in the 50–54 years age group may be attributable to factors such as hormonal changes associated with menopause which affect vaginal and cervical epithelium, making it more susceptible to HPV infections [27]. Additionally, immune senescence, or the natural decline in immune function with age [29], may contribute to the reactivation or persistence of latent HR-HPV infections in older women.

Our study found no significant association between the baseline participant factors and HR-HPV infections, and this lack of association suggests that HR-HPV infections may be widespread across various demographic and behavioural profiles within the population of WLHIV. It also highlights the potential influence of the immunosuppressive state induced by HIV on the susceptibility to HR-HPV, overshadowing other sociodemographic and behavioural risk factors. However, our study identified that specific factors such as CD4+ cell count below 560 cells/μL and HPV 16 or 18 co-infection were associated with multiple HR-HPV infections. The finding of a significantly higher risk of HPV infections among HIV-infected women with a serum CD4+ cell count below 560 cells/μL is consistent with the findings from previous studies where a higher HR-HPV prevalence was recorded in HIV-infected women with lower CD4+ cell counts [12,30]. This is based on the understanding that a lower CD4+ cell count, indicative of more advanced immunosuppression, impairs the body’s ability to clear HPV infections, thereby increasing the likelihood of multiple HR-HPV infections [30]. This finding emphasizes the importance of maintaining optimal immune function through ART to mitigate the risk of HPV co-infections and their potential complications in WLHIV. Furthermore, the finding of an independent association between HPV 16 or 18 co-infection and multiple HR-HPV infections suggests a synergistic pathogenic mechanism that exacerbates the infection risk and the high oncogenic potential of HPV 16 and 18 responsible for a significant proportion of cervical cancers globally [1,31] which underscores the need for extended-spectrum genotype-specific monitoring and interventions.

The findings of our study have several important implications. Firstly, they highlight the critical need for regular and comprehensive HPV screening programs in addition to vaccinations among WLHIV. Secondly, the association between lower CD4+ cell counts, and multiple HR-HPV infections reinforces the importance of effective ART adherence to maintain immune function and reduce the burden of cervical cancer. However, the study has a few limitations. First, as the participating women were enrolled in the urban Lagos metropolis with the exclusion of those living in the slums and suburban areas of Lagos, the study findings can only be these settings in Lagos. Secondly, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, we are unable to infer causality inference in the observed associations between the identified factors and multiple HR-HPV infections. Finally, as the study was conducted in an HIV treatment centre where all the enrolled women were on combined ART, our findings may not be entirely representative of HIV-infected women who are not taking treatment.

Conclusions

Our study reveals that one in seven enrolled HIV-infected women had HR-HPV infections while one in 27 had multiple HR-HPV infections. None of the baseline participants’ factors was associated with HR-HPV infections. However, having a serum CD4+ cell count below 560 cells/μL and a co-infection with either HPV 16 or 18 genotype were significantly associated with the detection of multiple HR-HPV infections. These findings provide valuable insights into the epidemiology of HR-HPV infections and highlight the need for targeted screening, effective ART management, and vaccination programs to improve health outcomes and reduce the burden of cervical cancer in this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgements

Our deepest gratitude goes to all the participating women and staff of the HIV treatment clinic of the hospital who have contributed to this study. We also appreciate the staff of the Research Management Office of the College of Medicine, University of Lagos staff for their support in securing the funding for the primary study in this article.

Funding

The lead author (KSO) received funding for this work from the National Cancer Institute and Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers K43TW011930 and D43TW010934. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors. It does not necessarily represent the official views of the Conquer Cancer Foundation, the National Cancer Institute, Fogarty International Center, or the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in the conception, the decision to publish, or the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests in the conduct and publication of the study in this article.

Human ethics and consent to participate

Approval for the primary study [14] was granted by the Health Research Ethics Committees of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (ADM/DSCST/HREC/APP/5443) and College Medicine University of Lagos (CMUL/HREC/07/22/1075). The research was conducted ethically according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Before enrollment, all study participants provided written informed consent, and a rigorous commitment to maintaining the privacy and confidentiality of participants’ information was upheld during and after the study’s completion.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Contributor Information

Kehinde S. OKUNADE, University of Lagos

Kabir B. BADMOS, University of Lagos

Austin OKORO, Lagos University Teaching Hospital.

Nicholas A. AWOLOLA, University of Lagos

Francisca O. NWAOKORIE, College of Medicine of the University of Lagos

Hameed ADELABU, University of Lagos.

Iyabo Y. ADEMUYIWA, University of Lagos

Temitope V. ADEKANYE, Lagos University Teaching Hospital

Packson O. AKHENAMEN, Lagos University Teaching Hospital

Elizabeth ODOH, Lagos University Teaching Hospital.

Chinelo OKOYE, Lagos University Teaching Hospital.

Alani S. AKANMU, University of Lagos

Adekunbiola A. BANJO, University of Lagos

Rose I. ANORLU, University of Lagos

Jonathan S. BEREK, Stanford University School of Medicine

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (KSO) upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Okunade KS. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore) 2020;40:602–8. 10.1080/01443615.2019.1634030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh D, Vignat J, Lorenzoni V, Eslahi M, Ginsburg O, Lauby-Secretan B, et al. Global estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2020: a baseline analysis of the WHO Global Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative. Lancet Glob Health 2022. 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00501-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sankaranarayanan R. Overview of Cervical Cancer in the Developing World. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2006;95 Suppl 1:S205–10. 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Vuyst H, Lillo F, Broutet N, Smith JS. HIV, human papillomavirus, and cervical neoplasia and cancer in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Eur J Cancer Prev 2008;17:545–54. 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f75ea1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massad LS, Xie X, D’Souza G, Darragh TM, Minkoff H, Wright R, et al. Incidence of cervical precancers among HIV-seropositive women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:606.e1-8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ssentongo P, Angeletti PC, Issiaka Maiga A, Zheng Y, Musa J, Kim K, et al. Accelerated Epigenetic Age Among Women with Invasive Cervical Cancer and HIV-Infection in Nigeria. Frontiers in Public Health | Www.Frontiersin.Org 2022;1:834800. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.834800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clifford GM, Gonçalves MAG, Franceschi S, HPV and HIV Study Group. Human papillomavirus types among women infected with HIV: a meta-analysis. AIDS 2006;20:2337–44. 10.1097/01.aids.0000253361.63578.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu G, Sharma M, Tan N, Barnabas R V. HIV-positive women have higher risk of human papilloma virus infection, precancerous lesions, and cervical cancer. AIDS 2018;32:795–808. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghebre RG, Grover S, Xu MJ, Chuang LT, Simonds H. Cervical cancer control in HIV-infected women: Past, present and future. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2017;21:101–8. 10.1016/j.gore.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okunade KS, Badmos KB, Soibi-Harry AP, Garba S-R, Ohazurike EO, Ozonu O, et al. Cervical Epithelial Abnormalities and Associated Factors among HIV-Infected Women in Lagos, Nigeria: A Cytology-Based Study. Acta Cytol 2022:1–9. 10.1159/000527905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209–49. 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ezechi OC, Ostergren PO, Nwaokorie FO, Ujah IAO, Odberg Pettersson K. The burden, distribution and risk factors for cervical oncogenic human papilloma virus infection in HIV positive Nigerian women. Virol J 2014;11:5. 10.1186/1743-422X-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashaka OS, Omoare AA, James AB, Adeyemi OO, Oladiji F, Adeniji KA, et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Genital Human Papillomavirus Infections among Women in Lagos, Nigeria. Trop Med Infect Dis 2022;7:386. 10.3390/tropicalmed7110386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okunade KS, Badmos KB, Okoro AC, Ademuyiwa IY, Oshodi YA, Adejimi AA, et al. Comparative Assessment of p16/Ki-67 Dual Staining Technology for cervical cancer screening in women living with HIV (COMPASS-DUST)-Study protocol. PLoS One 2023;18. 10.1371/journal.pone.0278077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okunade K, et al. Development of Antepartum Risk Prediction Model for Postpartum Haemorrhage in Lagos, Nigeria: A Prospective Cohort Study (predict-PPH study). Int J Gynecol Obstet 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weir CB, Jan A. BMI Classification Percentile And Cut Off Points. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher LD. Self-designing clinical trials. Stat Med 1998;17:1551–62. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Traore B, Kassogue Y, Diakite B, Diarra F, Cisse K, Kassogue O, et al. Prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus genotypes in outpatient Malian women living with HIV: a pilot study. BMC Infect Dis 2024;24:513. 10.1186/s12879-024-09412-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menon S, Wusiman A, Boily MC, Kariisa M, Mabeya H, Luchters S, et al. Epidemiology of HPV Genotypes among HIV Positive Women in Kenya: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0163965. 10.1371/journal.pone.0163965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogale AL, Belay NB, Medhin G, Ali JH. Molecular epidemiology of human papillomavirus among HIV infected women in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Virol J 2020;17:179. 10.1186/s12985-020-01448-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okoye JO, Ofodile CA, Adeleke OK, Obioma O. Prevalence of high-risk HPV genotypes in sub-Saharan Africa according to HIV status: a 20-year systematic review. Epidemiol Health 2021;43:e2021039. 10.4178/epih.e2021039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ezeanochie M, Olasimbo P. Awareness and uptake of human papilloma virus vaccines among female secondary school students in Benin City, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci 2020;20:45–50. 10.4314/ahs.v20i1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okunade KS, Sunmonu O, Osanyin GE, Oluwole AA. Knowledge and Acceptability of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination among Women Attending the Gynaecological Outpatient Clinics of a University Teaching Hospital in Lagos, Nigeria. J Trop Med 2017;2017. 10.1155/2017/8586459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adepoju P. Nigeria targets almost 8 million girls with HPV vaccine. The Lancet 2023;402:1612. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02450-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aimagambetova G, Babi A, Issanov A, Akhanova S, Udalova N, Koktova S, et al. The Distribution and Prevalence of High-Risk HPV Genotypes Other than HPV-16 and HPV-18 among Women Attending Gynecologists’ Offices in Kazakhstan. Biology (Basel) 2021;10:794. 10.3390/biology10080794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Babi A, Issa T, Issanov A, Akilzhanova A, Nurgaliyeva K, Abugalieva Z, et al. Prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus infection among Kazakhstani women attending gynecological outpatient clinics. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021;109:8–16. 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarke MA, Risley C, Stewart MW, Geisinger KR, Hiser LM, Morgan JC, et al. Age-specific prevalence of human papillomavirus and abnormal cytology at baseline in a diverse statewide prospective cohort of individuals undergoing cervical cancer screening in Mississippi. Cancer Med 2021;10:8641–50. 10.1002/cam4.4340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kombe Kombe AJ, Li B, Zahid A, Mengist HM, Bounda G-A, Zhou Y, et al. Epidemiology and Burden of Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases, Molecular Pathogenesis, and Vaccine Evaluation. Front Public Health 2020;8:552028. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.552028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee K-A, Flores RR, Jang IH, Saathoff A, Robbins PD. Immune Senescence, Immunosenescence and Aging. Frontiers in Aging 2022;3:900028. 10.3389/fragi.2022.900028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Vuyst H, Lillo F, Broutet N, Smith JS. HIV, human papillomavirus, and cervical neoplasia and cancer in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 2008;17:545–54. 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f75ea1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denny L, Adewole I, Anorlu R, Dreyer G, Moodley M, Smith T, et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution in invasive cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Cancer 2014;134:1389–98. 10.1002/ijc.28425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (KSO) upon reasonable request.