Abstract

Background

The role of obesity on dyspnea in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients remains unclear. We aimed to provide an assessment of dyspnea in COPD patients according to their Body Mass Index (BMI) and to investigate the impact of obesity on dyspnea according to COPD severity.

Methods

One hundred and twenty seven COPD patients with BMI ≥ 18.5 kg/m² (63% male, median (interquartile range) post bronchodilator forced expiratory volume of 1 second (post BD FEV1) at 51 (34–66) % pred) were consecutively included. Dyspnea was assessed by mMRC (Modified medical research council) scale. Lung function tests were recorded, and emphysema was quantified on CT-scan (computed tomography-scan).

Results

Twenty-five percent of the patients were obese (BMI ≥ 30kg/m²), 66% of patients experienced disabling dyspnea (mMRC ≥ 2). mMRC scores did not differ depending on BMI categories (2 (1–3) for normal weight, 2 (1–3) 1 for overweight and 2 (1–3) for obese patients; p = 0.71). Increased mMRC scores (0–1 versus 2–3 versus 4) were associated with decreased post BD-FEV1 (p < 0.01), higher static lung hyperinflation (inspiratory capacity/total lung capacity (IC/TLC), p < 0.01), reduced DLCO (p < 0.01) and higher emphysema scores (p < 0.01). Obese patients had reduced static lung hyperinflation (IC/TLC p < 0.01) and lower emphysema scores (p < 0.01) than non-obese patients. mMRC score increased with GOLD grades (1–2 versus 3–4) in non-obese patients but not in obese patients, in association with a trend towards reduced static lung hyperinflation and lower emphysema scores.

Conclusion

By contrast with non-obese patients, dyspnea did not increase with spirometric GOLD grades in obese patients. This might be explained by a reduced lung hyperinflation related to the mechanical effects of obesity and a less severe emphysema in severe COPD patients with obesity.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, dyspnea, lung function, pulmonary emphysema

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and obesity are two major health issues. According to the World Health Organization, the prevalence of obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m², has doubled since 1980, reaching 650 million in 2016.1 Obesity is common in COPD patients, ranging from 15 to 54%.2 Although the impact of both of these health problems on respiratory physiology has been widely studied in isolation, the impact of their combination on dyspnea remains unclear.

COPD is frequently associated with static and dynamic hyperinflation, especially when emphysema is associated. Various ways may describe lung static hyperinflation, including an increase in functional residual capacity (FRC), in residual volume (RV), in RV/total lung capacity (TLC) ratio or a decrease in inspiratory capacity (IC) and IC/TLC ratio.3 Obesity is associated with a decrease in expiratory reserve volume (ERV) (and consequently in FRC) with an exponential relation between BMI increase and ERV decrease.4 Thus, it has been demonstrated that BMI increase in COPD patients is associated with reduced lung hyperinflation.3 Obesity might therefore provide a ventilatory mechanical advantage to COPD patients.

Dyspnea is the most common symptom of COPD. Lung hyperinflation is one of the factors that contribute to dyspnea in COPD.5,6 Obesity also leads to dyspnea7 but is also associated with less lung hyperinflation. There is no current consensus on the role of obesity on dyspnea in COPD patients, with studies showing conflicting results.2,8 Some studies with large COPD cohorts have described more dyspnea intensity after FEV1 (Forced expiratory volume in 1 second) adjustment9–12 (but not after emphysema severity adjustment2) in COPD obese patients in comparison with COPD non-obese patients. Other studies, with small COPD populations, have found equal dyspnea intensity between COPD obese patients and COPD non-obese patients,13–18 in association with less static and dynamic lung hyperinflation,16 without having performed analysis on the quantification of emphysema.

This study aimed to provide an assessment of dyspnea in COPD patients according to their BMI, to analyse the factors related to dyspnea in COPD patients, and to investigate the impact of obesity on dyspnea according to COPD severity, including spirometric GOLD grades and emphysema quantification.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Design

This single-center study was prospectively conducted by the Department of Respiratory Diseases (University Hospital of Reims) between October 2016 and May 2022. COPD patients were included in the RINNOPARI study (Recherche et INNOvation en PAthologie Respiratoire et Inflammatoire), an observational cohort of inflammatory chronic lung diseases. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Dijon EST I on 31st May 2016 (N°2016-A00242-49) and by the French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products (ANSM) on 25th April 2016. Each patient signed a written informed consent form. The study was in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Consecutive COPD patients assessed in the Department of Respiratory Diseases at the University Hospital of Reims, with BMI ≥ 18.5 kg/m² were considered for inclusion. The diagnosis of COPD was based on clinical and functional assessments with a FEV1/FVC <0.7 after bronchodilation. At inclusion, all patients were stable with no acute exacerbation of COPD for 4 weeks. Patients with asthma, cystic fibrosis, tuberculosis, cancer, or other chronic respiratory diseases were excluded.

Demographical and Clinical Characteristics

Demographic data (age, sex), anthropometric characteristics (height, weight, BMI), smoking status, medical treatments (COPD treatment, antidepressant and anxiolytic), medical comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), right-heart failure, left-heart failure, coronary artery disease, arrhythmia, osteoporosis, depression) were systematically recorded.

Symptoms Scores

Dyspnea in daily living was evaluated using the mMRC (Modified Medical Research Council) scale. This unidimensional scale consists of five statements describing the range of dyspnea from none (grade 0) to almost complete incapacity (grade 4).19

Anxiety and depression were assessed by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).20,21

Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs)

PFTs were performed according to the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society guidelines22 (BodyBox 5500 Medisoft Sorinnes, Belgium) and included measurements of post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), FEV1/FVC ratio, expiratory reserve volume (ERV), inspiratory capacity (IC), residual volume (RV), total lung capacity (TLC), diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) and rate constant for carbon monoxide uptake (DLCO/VA).23,24 Results were expressed in percentage of predicted values.25,26 The severity of COPD was determined by spirometric classification (GOLD 1: FEV1 ≥ 80%; GOLD 2: 50% ≤ FEV1 < 80%; GOLD 3: 30% ≤ FEV1 < 50%; GOLD 4: FEV1 < 30%).27

Arterial Blood Gases

Arterial blood gases were measured in the morning in a sitting position on room air.

Six-Minute Walk Test

The six-minute walk test (6MWT) was performed in a 30-meter long, flat, covered corridor, marked meter-by-meter, according to the European Respiratory Society and American Thoracic Society guidelines.28 Continuous monitoring of oxyhaemoglobin saturation and heart rate was performed during 6MWT. Dyspnea was evaluated by the Borg scale at the beginning and the end of the test.

Emphysema Quantification Using Chest Computed Tomography Scan (CT-Scan)

A visual score from 0 to 4 was assigned to each lobe, based on the extent of tissue destruction, where 0 = no emphysema, 1 = 1% to 25% emphysematous, 2 = 26% to 50%, 3 = 51% to 75%, and 4 ≥75%.29,30 The results present the sum of the different lobes.

Laboratory Parameters

Hemoglobin, eosinophils, fibrinogen, total protein, and N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP) were determined from a blood sample at inclusion.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables were described as median and interquartile range. Qualitative variables were expressed as number and percentage. Patients were split into 3 groups according to their BMI: normal weight for BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m², overweight for BMI between 25 kg/m² to 29.9 kg/m² and obesity for BMI ≥30 kg/m². Variables associated with BMI were studied using Chi-square tests or Fisher tests or Kruskal Wallis tests according to the application’s conditions. For the significant p values, we conducted Dunn tests to show where the differences lie.

Patients were also separated into 3 groups according to their dyspnea intensity in daily living: mMRC 0–1, mMRC 2–3 and mMRC 4. Variables associated with mMRC were analyzed using Chi-square tests or Fisher tests or the Kruskal-Wallis test according to the application’s conditions. For the significant p values, we conducted Dunn tests to show where the differences lie.

Comparison of mMRC scores, Borg after 6MWT scores, RV, IC/TLC and emphysema scores according to GOLD grades (1–2 versus 3–4) by subgroup of patients according to BMI was studied using Wilcoxon tests. For this comparison, quantitative variables were described as median and interquartile range. Then, 3 × 2 ANOVA (obesity status × GOLD grades) was performed.

A first multivariate analysis using an ascending stepwise logistic regression model for dyspnea (mMRC ≥ 2 versus mMRC < 2) by subgroup of IMC (normal weight, underweight and obesity) was performed. Variables proposed were FEV1 and IC/TLC.

A second multivariate analysis using an ascending stepwise logistic regression model for dyspnea (mMRC ≥ 2 versus mMRC < 2) by subgroup of GOLD grades (1–2 versus 3–4) was performed. Variables proposed were quantitative BMI and emphysema score.

Spearman correlation between mMRC scores and PFT’s indices were studied.

A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients Characteristics

One hundred and twenty-seven COPD patients were included in this study. Of these, 63% were male, the median (interquartile) age was 63 (56–67) years, and the median tobacco consumption was 40 (30–58) pack-years. All patients performed a spirometry, 112 patients a plethysmography, 93 patients a DLCO measurement and 89 patients a 6MWT. They were missing data for the main outcomes for 6 patients for mMRC scores and for 3 patients for Borg scores during the 6MWT. The population included a broad range of airflow obstruction: 20 patients GOLD grade 1 (16%), 55 GOLD grade 2 (43%), 35 GOLD grade 3 (28%) and 17 GOLD grade 4 (13%).

Clinical characteristics, lung function tests, and laboratory parameters of the patients are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Thirty-nine percent of patients were normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m²), 36% overweight (25–29.9 kg/m²) and 25% obese (≥30 kg/m²). Among the 32 patients with obesity, 20 patients had a BMI between 30 and 34.9 kg/m², 11 patients a BMI between 35 and 34.9 kg/m² and 1 patient a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m². The maximal BMI was 40.6 kg/m². Comparison among the BMI categories showed that obesity was associated with severe OSAS, reduced ERV and increased post BD FEV1, DLCO and DLCO/VA. There was no significant difference in laboratory parameters’ Results between the BMI categories.

Table 1.

Patients Characteristics Depending on BMI Groups According to World Health Organization Categories

| Normal Weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m²) (n=50) | Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m²) (n=45) | Obesity (≥ 30 kg/m²) (n=32) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 27 (54%) | 30 (67%) | 23 (72%) | 0.21 |

| Age (years) | 63 (54–64) | 65 (57–71) | 63 (57–68) | 0.13 |

| Weight (kg) | 63 (55–71) | 82 (75-90) | 98 (91–104) | < 0.01# |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 17 (16–18) | 22 (20–24) | 28 (26–28) | < 0.01# |

| Smoking history | ||||

| Former smoker | 30 (60%) | 29 (64%) | 23 (72%) | 0.25 |

| Pack-years | 50 (32–60) | 42 (33–54) | 40 (34–60) | 0.81 |

| BODE score (n=80) | 7 (6–8) | 4 (2–6) | 3 (2–4) | 0.10 |

| COPD treatment | ||||

| LABA | 28 (56%) | 26 (58%) | 19 (60%) | 0.67 |

| Very LABA | 7 (14%) | 4 (9%) | 3 (9%) | 0.50 |

| LAMA | 30 (60%) | 25 (56%) | 20 (63%) | 0.35 |

| Inhaled CS | 15 (30%) | 18 (40%) | 17 (53%) | 0.32 |

| Oral CS | 2 (6%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (3%) | 0.93 |

| Long term O2 therapy | 5 (10%) | 6 (13%) | 6 (19%) | 0.59 |

| NIV | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (9%) | 0.06 |

| PR (12 months) | 7 (14%) | 6 (13%) | 6 (19%) | 0.61 |

| LVR | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.62 |

| Exacerbation | ||||

| 12 months | 32 (64%) | 26 (58%) | 21 (67%) | 0.32 |

| 3 months | 23 (46%) | 19 (42%) | 14 (44%) | 0.88 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 16 (32%) | 26 (58%) | 20 (63%) | 0.88 |

| Diabetes | 4 (8%) | 8 (18%) | 7 (22%) | 0.18 |

| Severe OSAS | 0 (0%) | 6 (13%) | 12 (38%) | < 0.01 |

| Right heart failure | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.73 |

| Left heart failure | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.26 |

| Coronary artery disease | 5 (10%) | 10 (22%) | 5 (16%) | 0.60 |

| Arrhythmia | 4 (8%) | 8 (18%) | 5 (16%) | 0.85 |

| Osteoporosis | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (6%) | 0.74 |

| Depression | 12 (24%) | 15 (33%) | 5 (16%) | 0.20 |

| HAD scale (n=117) | ||||

| Anxiety HAD score | 9 (5–12) | 8 (5–12) | 7 (5–13) | 0.59 |

| Anxiety HAD score > 10 | 16 (34%) | 13 (33%) | 9 (29%) | 0.89 |

| Depression HAD score | 5 (3–8) | 6 (3–9) | 6 (3–10) | 0.69 |

| Depression HAD score > 10 | 7 (15%) | 7 (18%) | 7 (23%) | 0.69 |

| Antidepressant | 2 (4%) | 3 (7%) | 2 (6%) | 0.88 |

| Anxiolytic | 6 (12%) | 7 (15%) | 4 (13%) | 0.75 |

Note: Data are expressed as median (interquartile range) and as number (percentage) of patients. P < 0.05 are indicated in bold front. #Dunn test: every groups were differents.

Abbreviations: LABA, Long-acting β2-agonists; LAMA, Long-acting anticholinergics; CS, corticosteroids; NIV, non invasive ventilation; PR, pulmonary rehabilitation; LVR, lung volume reduction; OSAS, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; HAD scale, Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale.

Table 2.

Lung Function Tests and Laboratory Parameters Depending on BMI Groups According to World Health Organization Categories

| Normal Weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m²) (n=50) | Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m²) (n=45) | Obesity (≥ 30 kg/m²) (n=32) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary function tests (n=127) | ||||

| Post BD FEV1 (% pred) | 40 (29–63) | 56 (46–72) | 52 (43–65) | 0.04 (1) |

| ERV (% pred) | 108 (87–146) | 82 (56–102) | 66 (47–104) | < 0.01 |

| IC (% pred) (n=99) | 76 (61–94) | 88 (70–101) | 105 (80–117) | 0.06 |

| IC/TLC (n=97) | 23 (20–30) | 30 (23–35) | 32 (29–38) | < 0.01 (4) |

| RV (% pred) (n=111) | 208 (175–250) | 183 (151–218) | 181 (167–222) | 0.21 |

| RV/TLC (n=111) | 56 (47–61) | 57 (53–63) | 56 (53–63) | 0.13 |

| TLC (% pred) (n=112) | 126 (112–144) | 123 (109–136) | 125 (108–136) | 0.50 |

| DLCO (% pred) (n=92) | 38 (25–50) | 48 (30–70) | 61 (40–74) | < 0.01 (2) |

| DLCO/VA (% pred) (n=93) | 45 (30–58) | 54 (37–74) | 66 (53–93) | < 0.01 (3) |

| Arterial blood gases (n=110) | ||||

| pH | 7.42 (7.40–7.44) | 7.42 (7.40–7.43) | 7.41 (7.39–7.43) | 0.82 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 76 (70–82) | 74 (66–84) | 76 (67–86) | 0.66 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 37 (36–42) | 40(36–41) | 39 (37–43) | 0.43 |

| HCO3− (mmol.L-1) | 25 (23–26) | 25 (24–26) | 25 (23–28) | 0.56 |

| 6-minute walk test (n=89) | ||||

| O2 during the test (n=8) | 2 (6%) | 3 (10%) | 3 (12%) | 0.65 |

| O2 flow (L/min) | 2 (1–2) | 1 (1–1) | 3 (1–3) | 0.22 |

| SpO2 at rest (%) | 97 (95–98) | 95 (94–97) | 95 (92–97) | 0.02 (3) |

| SpO2 after 6MWT (%) | 92 (88–96) | 93 (89–96) | 93 (87–95) | 0.75 |

| Distance (m) | 416 (306–471) | 369 (300–440) | 337 (270–405) | 0.16 |

| Distance (% pred) | 70 (57–82) | 73 (62–83) | 74 (53–89) | 0.61 |

| CT-scan (n=118) | ||||

| Emphysema | 41 (89%) | 30 (73%) | 19 (61%) | 0.02 |

| Emphysema score | 10 (5–14) | 4 (0–8) | 3 (0–7) | < 0.01 (1) |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) (n=122) | 14.6 (13.4–15.3) | 14.2 (13.6–15.4) | 15.1 (14.2–15.5) | 0.19 |

| Eo (G/L) (n=121) | 200 (100–350) | 200 (100–300) | 200 (100–300) | 0.69 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) (n=100) | 3.8 (3.4–4.5) | 3.9 (3.5–4.4) | 3.9 (3.3–4.8) | 0.92 |

| NT-pro-BNP (pg/mL) (n=76) | 49 (31–114) | 64 (34–273) | 56 (36–139) | 0.62 |

Notes: Data are expressed as median (interquartile range) and as number (percentage) of patients. P < 0.05 are indicated in bold front. (1) Dunn test: no difference between overweight and obesity groups. (2) Dunn test: normal weight and obesity groups are only differents. (3) Dunn test: no difference between normal weight and overweight groups. (4) Dunn test: no difference between normal weight and obesity groups.

Abbreviations: Post BD FEV1, post bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second; ERV, expiratory reserve volume; IC, inspiratory capacity; RV, residual volume; TLC, total lung capacity; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; 6MWT, 6-minute walk test; Eo, eosinophils; NT-pro-BNP, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide.

Dyspnea Assessment

Median mMRC score was 2 (1–3). Eighty-nine percent of the patients experienced dyspnea in daily living with a mMRC score >0, 66% disabling dyspnea with a mMRC score ≥2 and 18% dyspnea on the slightest exertion with a mMRC score = 4. Sixty-nine percent of patients described dyspnea on exertion (Borg > 3). There was no significant difference between the different BMI categories regarding dyspnea (Table 3).

Table 3.

Dyspnea and Quality of Life Assessment Depending on BMI Groups According to World Health Organization Categories

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m²) (n=50) | Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m²) (n=45) | Obesity (≥ 30 kg/m²) (n=32) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mMRC scale (n=121) | ||||

| mMRC score | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.71 |

| mMRC = 0 | 3 (6%) | 6 (14%) | 4 (13%) | 0.64 |

| mMRC = 1 | 15 (32%) | 8 (19%) | 5 (16%) | |

| mMRC = 2 | 12 (26%) | 8 (19%) | 9 (29%) | |

| mMRC = 3 | 10 (21%) | 11 (25%) | 8 (26%) | |

| mMRC = 4 | 7 (15%) | 10 (23%) | 5 (16%) | |

| Borg scale (n=86) | ||||

| Borg score at rest | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.66 |

| Borg at rest ≥ 1 | 16 (45%) | 9 (32%) | 12 (50%) | 0.38 |

| Borg after 6MWT | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–8) | 5(3–7) | 0.93 |

| Borg after 6MWT ≥ 1 | 34 (100%) | 25 (89%) | 24 (100%) | 0.05 |

| Borg after 6MWT > 3 | 24 (71%) | 18 (64%) | 17 (71%) | 0.84 |

Note: Data are expressed as median (interquartile range) and as number (percentage) of patients.

Abbreviations: mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; 6MWT, 6 minute walk test.

Relationship Between mMRC Scores and Clinical Characteristics and Respiratory Assessment

Dyspnea intensity according to mMRC scale was associated with more severe lung impairment (higher airflow obstruction assessed by FEV1, higher static hyperinflation assessed by IC/TLC, higher emphysema score, higher impairment of DLCO, lower PaO2, and lower covered distance in 6MWT) and higher anxiety and depression symptom scores (Table 4). By contrast, we did not find an association between the mMRC scale and exacerbation rate in the 3rd and 12th months before inclusion. Concerning PFTs, the mMRC score was correlated with lower FEV1 (correlation coefficient: −0.427; p < 0.0001), lower DLCO and DLCO/VA (respectively, correlation coefficients of −0.427; p < 0.0001 and −0.317; p = 0.002), lower IC/TLC ratio, IC and higher RV (respectively, −0.299; p = 0.003, −0.369; p < 0.0001 and +0.230; p = 0.018). The mMRC score was also correlated with higher emphysema score (correlation coefficient: +0.343; p = 0.0002).

Table 4.

Clinical Characteristics and Lung Function Tests According to mMRC Scores

| mMRC 0–1 (n=41) | mMRC 2–3 (n=58) | mMRC 4 (n=22) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 61 (57–67) | 63 (55–70) | 63 (59–67) | 0.80 |

| Male sex | 27 (66%) | 34 (59%) | 16 (73%) | 0.47 |

| BMI | 26 (22–30) | 28 (23–32) | 27 (24–30) | 0.27 |

| Former smoker | 19 (46%) | 44 (76%) | 17 (77%) | 0.01 |

| Pack-years | 40 (31–49) | 40 (22–60) | 46 (40–60) | 0.09 |

| Exacerbation | ||||

| 12 months | 21 (51%) | 41 (71%) | 15 (68%) | 0.36 |

| 3 months | 17 (41%) | 25 (43%) | 12 (55%) | 0.17 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 19 (46%) | 28 (48%) | 11 (50%) | 0.85 |

| Coronary artery disease | 5 (12%) | 11 (19%) | 2 (9%) | 0.47 |

| Arrhythmia | 6 (14%) | 7 (12%) | 3 (14%) | 0.81 |

| Right heart failure | 0 (0%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.68 |

| Left heart failure | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| Anxiety HAD score (n=116) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–11) | 11 (9–13) | 0.01(1) |

| Depression HAD score (n=116) | 3 (1–7) | 6 (4–8) | 10 (8–12) | <0.01(2) |

| Pulmonary function test (n=121) | ||||

| Post BD FEV1 (% pred) | 62 (50–77) | 49 (34–65) | 34 (23–51) | <0.01(5) |

| ERV (% pred) (n=103) | 98 (80–137) | 84 (62–110) | 95 (68–121) | 0.48 |

| IC (% pred) (n=99) | 97 (80–108) | 84 (65–103) | 75 (54–83) | <0.01(3) |

| IC/TLC (n=97) | 32 (27–37) | 29 (22–34) | 24 (16–29) | <0.01(1) |

| RV (% pred) (n=111) | 180 (138–215) | 198 (170–234) | 213 (174–260) | 0.07 |

| RV/TLC (n=111) | 56 (47–61) | 59 (54–67) | 62 (54–68) | 0.20 |

| TLC (% pred) (n=112) | 119 (109–136) | 125 (113–144) | 130 (114–135) | 0.35 |

| DLCO (% pred) (n=92) | 57 (45–66) | 42 (30–55) | 26 (18–44) | <0.01(4) |

| DLCO/VA (% pred) (n=93) | 59 (44–77) | 48 (36–61) | 40 (25–63) | 0.11 |

| Arterial blood gases (n=104) | ||||

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 79 (71–88) | 74 (67–83) | 70 (59–76) | <0.01(3) |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 39 (36–41) | 39 (36–42) | 39 (37–45) | 0.65 |

| 6-minute walk test (n=85) | ||||

| Borg scale after 6MWT | 3 (3–4) | 6 (4–7) | 8 (5–8) | <0.01(5) |

| Distance (m) | 470 (400–511) | 357 (301–430) | 297 (247–338) | <0.01(5) |

| CT-scan (n=118) | ||||

| Emphysema | 25 (66%) | 46 (84%) | 16 (84%) | 0.1 |

| Emphysema score | 3 (0–7) | 7 (3–11) | 39 (37–45) | <0.01(5) |

Notes: Data are expressed as median (interquartile range) and as number (percentage) of patients. P < 0.05 are indicated in bold front. (1) Dunn test: difference only between mMRC 0–1 and mMRC 4. (2) Dunn test: every groups were differents. (3) Dunn test: no difference between mMRC 0–1 and mMRC groupe 2–3. (4) Dunn test: difference between mMRC 0–1 and mMRC 4. (5) Dunn test: no difference between mMRC 2–3 and mMRC 4.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HAD score, Pre BD FEV1, pre bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second; TLC, total lung capacity; RV, residual volume; IC, inspiratory capacity; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon dioxide.

The multivariable analysis including FEV1 and IC/TLC in the different BMI categories showed that a mMRC score ≥2 was only associated with FEV1 in normal weight patients (OR = 0.925 IC[0.876–0.977]; p = 0.005) and only with IC/TLC in obese patients (OR = 0.861 IC[0.746–0.994]; p = 0.04).

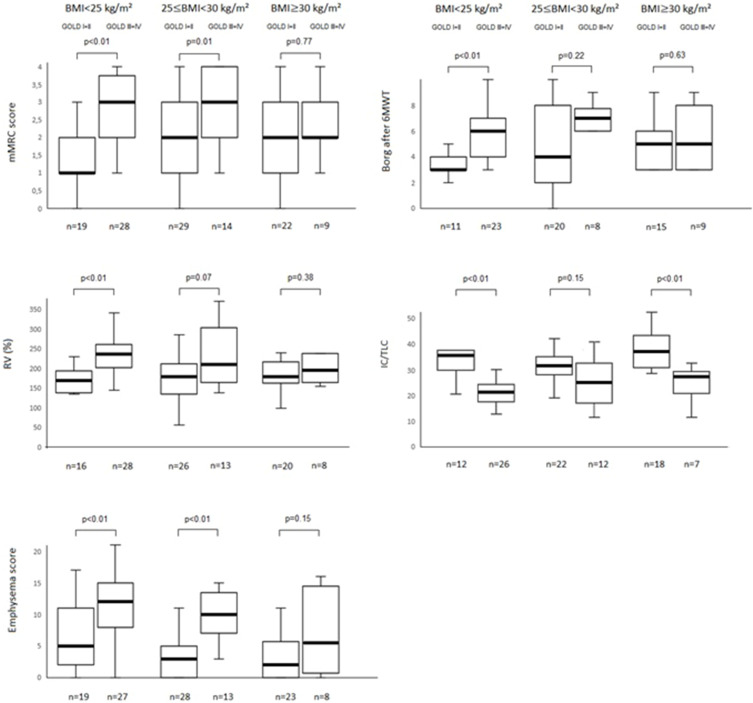

Figure 1 illustrates dyspnea assessment (according to mMRC and Borg after 6MWT scales), static hyperinflation (according to IC/TLC and RV) and emphysema scores according to BMI groups and GOLD grades (1–2 versus 3–4). mMRC scores are associated with GOLD grades for patients with a BMI < 30 kg/m², but not for obese patients. Dyspnea on exertion assessed by the Borg scale after 6MWT tends to show the same feature. Static hyperinflation assessed by RV and emphysema scores was also associated with GOLD grades for patients with BMI < 30 kg/m², but not for obese patients. The multivariable analysis including BMI and emphysema score in GOLD grades (1–2 and 3–4) showed that a mMRC score ≥2 was associated with increased BMI and emphysema scores in GOLD 1–2 but not in GOLD 3–4, subject to a low number of patients in this last group.

Figure 1.

mMRC scores, Borg after 6MWT, RV and emphysema scores according to the GOLD grades (1–2 versus 3–4) and BMI groups. Data are expressed as median (interquartile range). p value presented in the box corresponds to the comparison between GOLD1-2 and GOLD 3–4 patients according to BMI categories using Wilcoxon test. p value for 3×2 ANOVA (obesity status x GOLD grades) was <0.05 for all the figures (mMRC and Borg after 6MWT scores, RV (% pred)), IC/TLC and emphysema score.

Abbreviations: mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; 6MWT, six-minute walk test; RV, residual volume; BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

This study analyzed the relationships between dyspnea in daily living according to mMRC, BMI, and a complete respiratory assessment in COPD patients. Our results showed that in contrast to patients with BMI < 30 kg/m², dyspnea intensity in daily living did not increase with spirometric GOLD grades in obese patients, in association with a trend towards reduced static lung hyperinflation and lower emphysema scores.

Our data confirm that obesity is highly prevalent in COPD (25% of the patients in our study). Available data regarding the prevalence of obesity in COPD patients are variable, ranging from 15% to 54%.9,11,31–38 As observed in our cohort, obesity is more common in GOLD grades 1 and 2 and least prevalent in GOLD grade 4.39

The consequences of increased BMI on static lung volumes have been documented in COPD. In a large cohort of COPD patients, O’Donnell et al3 showed a decrease in ERV and RV and an increase in IC with increased BMI. In our study, we found similar results with reduced ERV and increased IC/TLC in obese patients, compared with other BMI categories. Studies assessing the effects of obesity on DLCO and associated measurements of alveolar volume (VA) and DLCO/VA have provided conflicting results. Some studies have reported DLCO decreases in obesity, likely due to a reduced VA or structural changes to the interstitium caused by increased lipid deposition40 and others have showed DLCO increases in severe obese patients, likely due to increased pulmonary blood volume,41,42 but the most common finding has been DLCO within normal ranges.43–45 DLCO/VA is usually similar or higher for patients with obesity in comparison with normal weight patients. In context of COPD, there are few data concerning the effects of obesity on these measurements. In our study, comparison among the BMI categories showed that obesity was associated with increased DLCO and DLCO/VA, in association with less severe airflow obstruction and less severe emphysema.

Dyspnea is one of the predominant complaints from patients with COPD. In a large French COPD cohort, with a wide range of airflow obstruction, 63% of patients had disabling dyspnea in daily living with a mMRC score ≥2.46 In our study, the median mMRC score was 2, and the proportion of patients with mMRC ≥2 was similar (66%).

As previously described in COPD, we observed that dyspnea was associated with FEV1, static hyperinflation, diffusing capacity and anxiety/depression.46,47 This analysis also showed the non-linear relationship between BMI, GOLD grades and dyspnea. In obese patients, the intensity of dyspnea was similar (mMRC around 2) whatever the GOLD grade, whereas mMRC scores increased with GOLD grades in patients with BMI < 30 kg/m² (Figure 1). As hyperinflation is a significant determinant of dyspnea in COPD patients,46–50 the phenomena of less hyperinflation, thus breathing at relatively lower lung volumes may lead to a mechanical advantage in obese patients with COPD. Ora et al16 showed, in 18 obese and 18 normal-weight COPD patients, matched for age, gender, smoking history, FEV1 and DLCO (but not for emphysema severity) that obese patients, in comparison with normal-weight patients, did not experience more dyspnea at rest and during incremental cycle exercise, in association with less static and dynamic hyperinflation. In our study, static hyperinflation assessed by RV did not increase with GOLD grades in obese patients, contrary to patients with BMI < 25 kg/m² (Figure 1). This might be partly related to the mechanical effects of obesity on lung volumes but also to less pulmonary emphysema (Figure 1), as BMI is also known to be inversely associated with the severity of emphysema independent of gender, age, and smoking history.51 Then, higher DLCO and DLCO/VA in patients with obesity, related to less severe airflow obstruction/less severe emphysema and/or obesity per se, could also explain partly relative lower intensity of dyspnea because presumably a higher DLCO represents a healthier alveolar capillary interface with potential for better gas exchange. Interestingly, exacerbation rate was not associated with BMI and GOLD grades in our study.

One of the strengths of our study is the assessment of the relationship between dyspnea according to the mMRC scale, BMI and an extensive respiratory assessment (6MWT, arterial blood gases, PFTs, CT-scan) in a prospective cohort of COPD patients.

This study has several limitations. It was conducted in a single centre, which may limit the generalization of the results. The number of patients included was relatively low, which may have limited the power of our statistical analyses in some sub-groups of patients. These results should be considered exploratory. As BMI is a simple measurement to use in clinical practice to assess obesity and is associated with dyspnea intensity in obese patients,52 we have considered BMI rather than body composition in this study. We then assessed lung hyperinflation through IC/TLC and RV, but other measures can be used with different meaning;53 eg we did not perform a cardiopulmonary exercise testing to assess dynamic hyperinflation. Moreover, we did not include in our study an echocardiographic assessment and/or right-heart catheterization to assess pulmonary hypertension or left-heart failure which are associated with dyspnea. At last, dyspnea was assessed by the mMRC and Borg scales which have limitations in COPD. Assessing the sensory and affective dimensions of dyspnea by using more recent tools like the Multidimensional Dyspnea Profile (MDP) may allow a more in-depth understanding of dyspnea symptoms in COPD.54 CT-scan assessment of emphysema severity was based on visual assessment only. A more robust assessment of CT-scan using Artificial Intelligence-based low attenuation volume percentage would be of interest to better characterize emphysema severity.55

Conclusion

This prospective study suggests that, contrary to patients with BMI < 30 kg/m², dyspnea intensity in daily living, according to the mMRC scale, did not increase with GOLD grades in obese patients. It shows that hyperinflation is a determinant of the mMRC score and that obesity is associated with less lung static hyperinflation and lower emphysema scores. Taken together, these results suggest that the relative lower intensity of dyspnea in obese patients with severe COPD might be partly related to less hyperinflation, related to mechanical effects of obesity with less emphysema severity in severe COPD patients with obesity.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the personnel of the Department of Pulmonary Medicine for the clinical/functional assessment of the patients.

Funding Statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. This study was funded by the Research and Innovation in Inflammatory Respiratory Diseases Project (RINNOPARI). This funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Abbreviations

ANSM, French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products; BMI, body mass index; CT-scan, computed tomography scan; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide; ERV, expiratory reserve volume; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FRC, functional residual capacity; FVC, forced vital capacity; HAD, hospital anxiety depression scale; IC, inspiratory capacity; LVR, lung volume reduction; mMRC, modified medical research council; NT-pro-BNP, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide; OSAS, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; PFTs, pulmonary function tests; PR, pulmonary rehabilitation; RINNOPARI, Recherche et INNOvation en Pathologie Respiratoire et Inflammatoire; RV, residual volume; TLC, total lung capacity; 6MWT, six-minute walk test.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes—Dijon EST I, No. 2016-A00242-49) and was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02924818). All patients received detailed information about the methods used and gave their written consent.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study, design, execution, acquisition of data analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

GD reports personal fees from Chiesi, GSK and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. SD reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Sanofi-Aventis outside the submitted work. J.M. Perotin reports lecture honoraria from AstraZeneca and support for attending meetings from AstraZeneca and Chiesi; outside the submitted work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Obesity; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/obesity. Accessed July 9, 2024.

- 2.Zewari S, Vos P, van den Elshout F, Dekhuijzen R, Heijdra Y. Obesity in COPD: revealed and unrevealed issues. COPD. 2017;14(6):663‑73. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2017.1383978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Donnell DE, Deesomchok A, Lam YM, et al. Effects of BMI on static lung volumes in patients with airway obstruction. Chest. 2011;140(2):461‑8. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones RL, Nzekwu MMU. The effects of body mass index on lung volumes. Chest. 2006;130(3):827‑33. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.3.827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Donnell DE, Webb KA. Exertional breathlessness in patients with chronic airflow limitation. The role of lung hyperinflation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148(5):1351‑7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Donnell DE, Milne KM, James MD, de Torres JP, Neder JA. Dyspnea in COPD: new mechanistic insights and management implications. Adv Ther. 2020;37(1):41‑60. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01128-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boissière L, Perotin-Collard JM, Bertin E, et al. Improvement of dyspnea after bariatric surgery is associated with increased expiratory reserve volume: a prospective follow-up study of 45 patients. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0185058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neder JA. Exercise ventilation and dyspnea in the obese patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: « how much » versus « how well ». Chron Respir Dis. 2021;18:14799731211059172. doi: 10.1177/14799731211059172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.García-Rio F, Soriano JB, Miravitlles M, et al. Impact of obesity on the clinical profile of a population-based sample with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodríguez DA, Garcia-Aymerich J, Valera JL, et al. Determinants of exercise capacity in obese and non-obese COPD patients. Respir Med. 2014;108(5):745‑51. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambert AA, Putcha N, Drummond M, et al. Obesity is associated with increased morbidity in moderate to severe COPD. Chest. 2017;151(1):68‑77. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cecere LM, Littman AJ, Slatore CG, et al. Obesity and COPD: associated symptoms, health-related quality of life, and medication use. COPD. 2011;8(4):275‑84. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2011.586660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laviolette L, Sava F, O’Donnell DE, et al. Effect of obesity on constant workrate exercise in hyperinflated men with COPD. BMC Pulm Med. 2010;10(1):33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-10-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bautista J, Ehsan M, Normandin E, Zuwallack R, Lahiri B. Physiologic responses during the six minute walk test in obese and non-obese COPD patients. Respir Med. 2011;105(8):1189‑94. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maatman RC, Spruit MA, van Melick PP, et al. Effects of body mass index on task-related oxygen uptake and dyspnea during activities of daily life in COPD. Respirology. 2016;21(3):483‑8. doi: 10.1111/resp.12700 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ora J, Laveneziana P, Ofir D, Deesomchok A, Webb KA, O’Donnell DE. Combined effects of obesity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on dyspnea and exercise tolerance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(10):964‑71. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200904-0530OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ora J, Laveneziana P, Wadell K, Preston M, Webb KA, O’Donnell DE. Effect of obesity on respiratory mechanics during rest and exercise in COPD. J Appl Physiol. 2022;111:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaes AW, Franssen FM, Meijer K, Cuijpers MW, Wouters EF, Rutten EP, Spruit MA. Effects of body mass index on task-related oxygen uptake and dyspnea during activities of daily life in COPD. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones PW, Wedzicha JA. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54(7):581‑6. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.7.581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beekman E, Verhagen A. Clinimetrics: hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. J Physiother. 2018;64(3):198. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2018.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67(6):361‑70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanojevic S, Kaminsky DA, Miller MR, et al. ERS/ATS technical standard on interpretive strategies for routine lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2022;60(1):2101499. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01499-2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wanger J, Clausen JL, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(3):511‑22. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Culver BH, Graham BL, Coates AL, et al. Recommendations for a standardized pulmonary function report. an official American Thoracic Society technical statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(11):1463‑72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201710-1981ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quanjer PH, Tammeling GJ, Cotes JE, Pedersen OF, Peslin R, Yernault JC. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Eur Respir J. 1993;6(Suppl 16):5‑40. doi: 10.1183/09041950.005s1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graham BL, Brusasco V, Burgos F, et al. 2017 ERS/ATS standards for single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(1):1600016. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00016-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease - GOLD 2023 GOLD Report. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/. Accessed July 9, 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Holland AE, Spruit MA, Troosters T, et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1428‑46. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00150314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bankier AA, De Maertelaer V, Keyzer C, Gevenois PA. Pulmonary emphysema: subjective visual grading versus objective quantification with macroscopic morphometry and thin-section CT densitometry. Radiology. 1999;211(3):851‑8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.3.r99jn05851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fishman A, Fessler H, Martinez F, et al.; National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. Patients at high risk of death after lung-volume-reduction surgery. N E J Med. 2001;345(15):1075‑83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montes de Oca M, Tálamo C, Perez-Padilla R, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and body mass index in five Latin America cities: the PLATINO study. Respir Med. 2008;102(5):642‑50. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vozoris NT, O’Donnell DE. Prevalence, risk factors, activity limitation and health care utilization of an obese, population-based sample with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Can Respir J. 2012;19(3):e18–24. doi: 10.1155/2012/732618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vanfleteren LEGW, Spruit MA, Groenen M, et al. Clusters of comorbidities based on validated objective measurements and systemic inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(7):728‑35. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201209-1665OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Sidney S, et al. Body composition and functional limitation in COPD. Respir Res. 2007;8:7. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koniski ML, Salhi H, Lahlou A, Rashid N, El Hasnaoui A. Distribution of body mass index among subjects with COPD in the Middle East and North Africa region: data from the BREATHE study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1685‑94. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S87259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van den Bemt L, van Wayenburg CM, Smeele IJM, Schermer TRJ. Obesity in patients with COPD, an undervalued problem? Thorax. 2009;64(7):640. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.111716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Divo MJ, Cabrera C, Casanova C, et al. Comorbidity distribution, clinical expression and survival in COPD patients with different body mass index. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2014;1(2):229‑38. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.1.2.2014.0117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Şahin H, Naz İ, Varol Y, Kömürcüoğlu B. The effect of obesity on dyspnea, exercise capacity, walk work and workload in patients with COPD. Tuberk Toraks. 2017;65(3):202‑9. doi: 10.5578/tt.57228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huber MB, Kurz C, Kirsch F, Schwarzkopf L, Schramm A, Leidl R. The relationship between body mass index and health-related quality of life in COPD: real-world evidence based on claims and survey data. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):291. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01556-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Enache I, Oswald-Mammosser M, Scarfone S, et al. Impact of altered alveolar volume on the diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide in obesity. Respiration. 2011;81(3):217‑22. doi: 10.1159/000314585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubinstein I, Zamel N, DuBarry L, Hoffstein V. Airflow limitation in morbidly obese, nonsmoking men. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112(11):828‑32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-11-828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mafort TT, Rufino R, Costa CH, Lopes AJ. Obesity: systemic and pulmonary complications, biochemical abnormalities, and impairment of lung function. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2016;11:28. doi: 10.1186/s40248-016-0066-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharp JT, Henry JP, Sweany SK, Meadows WR, Pietras RJ. The total work of breathing in normal and obese men. J Clin Invest. 1964;43(4):728‑39. doi: 10.1172/JCI104957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ray CS, Sue DY, Bray G, Hansen JE, Wasserman K. Effects of obesity on respiratory function. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128(3):501‑6. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.128.3.501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biring MS, Lewis MI, Liu JT, Mohsenifar Z. Pulmonary physiologic changes of morbid obesity. Am J Med Sci. 1999;318(5):293‑7. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9629(15)40641-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ouaalaya EH, Falque L, Dupis JM, et al. The determinants of dyspnoea evaluated by the mMRC scale: the French Palomb cohort. Respir Med Res. 2021;79:100803. doi: 10.1016/j.resmer.2020.100803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perez T, Burgel PR, Paillasseur JL, et al. Modified medical research council scale vs baseline dyspnea index to evaluate dyspnea in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1663‑72. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S82408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nishimura K, Yasui M, Nishimura T, Oga T. Airflow limitation or static hyperinflation: which is more closely related to dyspnea with activities of daily living in patients with COPD? Respir Res. 2011;12:135. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hajiro T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, Ikeda A, Koyama H, Izumi T. Analysis of clinical methods used to evaluate dyspnea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(4):1185‑9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.4.9802091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ladeira I, Oliveira P, Gomes J, Lima R, Guimarães M. Can static hyperinflation predict exercise capacity in COPD? Pulmonology. 2021;2:S2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gu S, Li R, Leader JK, et al. Obesity and extent of emphysema depicted at CT. Clin Radiol. 2015;70(5):e14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2015.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hagenburg J, Bertin E, Salmon JH, et al. Association between obesity-related dyspnea in daily living, lung function and body composition analyzed by DXA: a prospective study of 130 patients. BMC Pulm Med. 2022;22(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s12890-022-01884-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith BM, Hoffman EA, Basner RC, Kawut SM, Kalhan R, Barr RG. Not all measures of hyperinflation are created equal: lung structure and clinical correlates of gas trapping and hyperexpansion in COPD: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (Mesa) COPD Study. Chest. 2014;145(6):1305‑15. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morélot-Panzini C, Gilet H, Aguilaniu B, et al. Real-life assessment of the multidimensional nature of dyspnoea in COPD outpatients. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(6):1668‑79. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01998-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wiedbrauck D, Karczewski M, Schoenberg SO, Fink C, Kayed H. Artificial intelligence-based emphysema quantification in routine chest computed tomography: correlation with spirometry and visual emphysema grading. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2023;48(3):388–393. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000001572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.