Abstract

RCASBP-M2C is a retroviral vector derived from an avian sarcoma/leukosis virus which has been modified so that it uses the envelope gene from an amphotropic murine leukemia virus (E. V. Barsov and S. H. Hughes, J. Virol. 70:3922–3929, 1996). The vector replicates efficiently in avian cells and infects, but does not replicate in, mammalian cells. This makes the vector useful for gene delivery, mutagenesis, and other applications in mammalian systems. Here we describe the development of a derivative of RCASBP-M2C, pGT-GFP, that can be used in gene trap experiments in mammalian cells. The gene trap vector pGT-GFP contains a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene. Appropriate insertion of the vector into genes causes GFP expression; this facilitates the rapid enrichment and cloning of the trapped cells and provides an opportunity to select subpopulations of trapped cells based on the subcellular localization of GFP. With this vector, we have generated about 90 gene-trapped lines using D17 and NIH 3T3 cells. Five trapped NIH 3T3 lines were selected based on the distribution of GFP in cells. The cellular genes disrupted by viral integration have been identified in four of these lines by using a 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends protocol.

Over the past 15 years, we have developed a series of retroviral vectors (the RCAS vectors) based on an avian sarcoma/leukosis virus (ASLV) (11, 14, 28). Although these vectors have been used widely in avian systems, they do not efficiently infect mammalian cells because the ASLV envelope glycoprotein does not recognize receptors on the surface of mammalian cells. One can extend the host range of the RCAS vectors by introducing the ASLV subgroup A receptor into mammalian cells or by generating transgenic mice expressing the ASLV subgroup A receptor (7, 10, 12). An alternative approach is to replace the env gene encoding the ASLV envelope glycoprotein with the env gene of the amphotropic murine leukemia virus (MLV) (5). The resulting virus, RCASBP-M2C, is still able to infect and replicate efficiently in avian cells. Although RCASBP-M2C can efficiently infect mammalian cells, it is replication defective in mammalian cells. Compared with an MLV-based vector, RCASBP-M2C has several advantages. Since it is replication competent in avian cells, high-titer virus stock can be prepared simply by passaging transfected avian cells. There is no need for a packaging cell line, which is required when a replication-defective MLV vector is used. Replication-defective MLV-based vectors can become replication competent by recombination with endogenous viruses. In contrast, the proviruses of ASLV-based vectors are stable when integrated into the genome of a mammalian cell. Neither mammalian cells nor the EV-0-derived chicken cells used to propagate the ASLV vectors have sequences closely related to the ASLV vectors. The absence of related sequences also makes an ASLV-based provirus easy to detect in mammalian cells. Since it is replication defective in mammalian cells, the ASLV-based virus is safe to handle. In contrast to physical gene-transfer methods, such as electroporation and calcium phosphate-DNA precipitation, which often introduce DNA into the genome in tandem arrays that frequently contain rearrangements, retroviral infection gives rise to integrated proviruses that have precisely defined structures. Retroviral integration does not cause gross rearrangements of the host cell genome. In general, the efficiency of stable gene transfer is higher when a viral infection protocol is used (25). With these advantages, the RCASBP-M2C vector should be useful for gene delivery and insertional mutagenesis in mammalian systems. Here we describe the development of a derivative of the RCASBP-M2C vector, pGT-GFP, that can be used for gene trapping in mammalian cells.

Gene trapping is a type of insertional mutagenesis that allows the easy identification of disrupted genes (20, 31). The concept behind gene trapping is that expression of a reporter gene that lacks promoter elements and an ATG initiation codon but contains an appropriate splice acceptor is dependent on the presence of a chromosomal transcription unit at the integration site. The transcript from the integrated reporter gene is a fusion between the 5′ part of the cellular gene and the reporter gene. Chimeric embryos derived from embryonic stem (ES) cells containing such fusions can be screened for interesting patterns of expression of the protein encoded by the gene fusion. This method can be used to identify developmentally regulated genes; the phenotype of the mutant animal can help to elucidate the function of the trapped gene. More recently, gene trapping has been used in an attempt to disrupt and tag essentially all of the genes in mouse ES cells (38).

One major problem of the gene trap strategy is that, in most cases, there is no simple way to preselect the ES cells for interesting genes or mutations before a significant effort is made to generate and analyze chimeric embryos. Some effort has been made to simplify the problem. For instance, Skarnes et al. modified a conventional gene trap vector so that the β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity encoded by the reporter gene was detected only if the cellular gene that was fused to the reporter gene contained an N-terminal signal sequence. In this system, the ES cells were preselected for integration into genes coding for secreted or cell surface proteins (32). Another group prescreened ES cells in vitro for a subset of ES cells in which βgeo fusion proteins (described below) were confined to the nucleus, in an attempt to trap genes that encode nuclear proteins (33). Alternatively, ES cells can be induced to differentiate in vitro. ES cells that gave rise to embryoid bodies with tissue-specific expression patterns of the fusion proteins were selected and used to generate mice for phenotypic studies (4, 30).

With the importance of the preselection of ES cells in mind, we developed an RCASBP-M2C-based gene trap vector, pGT-GFP, which allows the prescreening of mutagenized cells based on the subcellular localization of the GFP fusions. The subcellular localization of a fusion protein provides a starting point for functional studies. For instance, most transcription factors and chromosomal proteins are nuclear proteins. Similarly, cell surface proteins are likely to be either membrane components or signal transduction molecules. In gene trap experiments in both yeast (8) and mice (31, 33), β-gal activity encoded by gene fusions was detected in various subcellular localizations, suggesting that the amino-terminal portion of the fusion protein that is encoded by the cellular gene is sufficient, at least in some cases, to direct the fusion protein into particular cellular compartments, presumably based on its intrinsic subcellular distribution. In the gene trap experiment described by Tate et al., many of the βgeo gene fusions that encoded nuclear proteins have βgeo fused to open reading frames with nuclear localization signals or other hallmarks of nuclear proteins. In addition, antibodies raised against peptides derived from two trapped genes showed that the endogenous proteins have a subcellular distribution similar to that of the fused proteins (33). These observations support the idea that the subcellular localization of a protein fusion reflects the normal distribution of the product of the trapped cellular gene in the cell.

Most of the reported gene trap systems use bacterial β-gal or βgeo as the reporter. βgeo is a fusion of the neomycin resistance gene and the β-gal gene. We have used the gfp gene from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria as the reporter gene in the gene trap vector pGT-GFP. The gfp gene has been widely used as an indicator of gene expression and protein localization in different organisms, such as Caenorhabditis elegans (9), zebrafish (1, 2, 15, 22, 24), Drosophila melanogaster (6, 34, 37), and mouse (13, 27, 39, 40). Green fluorescent protein (GFP) provides a vital marker that reflects the dynamic nature of gene expression during development without fixation and staining of the tissues or cells. In contrast, β-gal activity provides a static view of gene expression during development and requires fixation and the addition of a chemical substrate to tissues or cells. Moreover, while GFP gives a clear picture of subcellular distribution, the β-gal substrate can diffuse, and an immunostaining procedure using an antibody against β-gal protein is required to determine the precise distribution of β-gal in cells. Although GFP has not been used as a reporter for gene trap experiments in mice, it has been used as a reporter in enhancer trap experiments in D. melanogaster to reveal gene expression patterns in various developmental stages (34, 37). Transgenic mouse lines that express unfused GFP were generated to label the whole animal (27) or specific tissues and cells (39, 40). The expression of a single copy of gfp-Hox gene fusion could be detected during various stages of mouse embryogenesis; the GFP expression pattern reflected the expression pattern of the Hox genes (13). These observations suggest that GFP or modified versions of GFP could be used in gene trap experiments in mice.

Although we believe that pGT-GFP can be used in mouse ES cells, we made the initial tests of the vector in mouse NIH 3T3 cells and dog D17 cells. Cells that expressed GFP were isolated. Some cells were chosen based on the subcellular localization of the GFP fusion, and the trapped genes were characterized. Of the four GFP fusion transcripts we characterized, two contained novel sequences, one contained a known gene, and one contained segments of a known gene and sequences that had not previously been reported. For the known gene, the splice acceptor preceding gfp was used appropriately, and the gfp is in frame with the disrupted cellular gene. The distribution of the GFP fusion was in reasonable accordance with the published distribution of the normal cellular protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

pGT-GFP (Fig. 1) was derived from the vector RCASBP-M2C (5). A gfp cassette containing a splice acceptor, the GFP coding sequence preceded by a 14-codon linker, and a unidirectional simian virus 40 (SV40) polyadenylation site was inserted at the end of the env gene in RCASBP-M2C. The gfp cassette was placed in the RCASBP-M2C vector in an orientation opposite to the viral genes. The gfp gene in the cassette was derived from the pGreen Lantern-1 plasmid (Life Technology, Gaithersburg, Md.). A NcoI site was introduced at the ATG initiation codon of gfp and a HindIII site was introduced immediately upstream of the TAA stop codon. The NcoI-HindIII fragment containing the GFP coding sequence without the TAA stop codon was inserted in the helper plasmid SACla12Nco (19) which contains a splice acceptor 42 bp upstream of the gfp insertion site. The 42 nucleotides encode the sequence Pro Leu Trp Pro Gly Gly Ser Trp Asp Val Gln Pro Thr Thr, in frame with gfp. These 14 amino acids should serve as a linker between the cellular protein and GFP. The SV40 intron and polyadenylation site were PCR amplified from pGreen Lantern-1 and inserted in the HindIII site just beyond the end of the GFP coding sequence. As a result of the PCR, a TAA stop codon was introduced in frame with the gfp gene, and a NotI site was added at the end of the polyadenylation site. The NotI site was used in subsequent cloning steps. This plasmid is called SACla12Nco-GFP/pA. Since the SV40 polyadenylation site is bidirectional, it could interfere with the transcription of the viral genes. To eliminate the polyadenylation motif that would be in the same orientation as the viral genes, plasmid SACla12Nco-GFP/pA was linearized at a unique HpaI site that is inside the polyadenylation site. The entire plasmid, except the region containing the polyadenylation site to be removed, was amplified by using a pair of PCR primers (TATTGCAGCTTATAATGGTTAC and GCAAGTAAAACCTCTACAAATG) that flank the polyadenylation site. The PCR product was circularized by using T4 DNA ligase. The resulting plasmid, SACla12Nco-GFP/pA(f), contains only a unidirectional polyadenylation site. The modified polyadenylation site was sequenced to check for PCR errors. Finally, a ClaI-NotI fragment of SACla12Nco-GFP/pA(f) containing the splice acceptor, the GFP coding sequence preceded by the 14-codon linker, and the unidirectional SV40 polyadenylation site was inserted in RCASBP-M2C(CM) to make pGT-GFP. RCASBP-M2C(CM) is a derivative of RCASBP-M2C; the MluI site near the site where the viral sequences were joined to the plasmid was removed, making the MluI site adjacent to the ClaI cloning site in RCASBP-M2C(CM) unique.

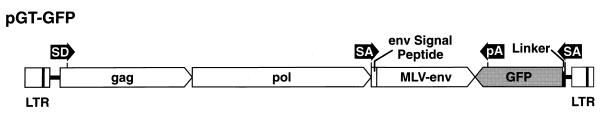

FIG. 1.

Schematic structure of the gene trap vector pGT-GFP. The long terminal repeats (LTR), gag, pol, and the sequence that encodes the envelope signal peptide are from the parental ASLV. The env gene is from an amphotropic MLV. The gfp trapping cassette, including the GFP coding sequence (GFP), the splice acceptor (SA), a 14-codon linker (Linker), and the polyadenylation signal (pA), is placed in an orientation opposite to the viral genes. SD, splice donor. Figure is not to scale.

Cell culture, transfection, and infection.

DF-1, a permanent fibroblast cell line, was derived from EV-0 chicken embryos (3, 16, 29). The cells were cultured in 1× Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) supplemented with 10% tryptose phosphate broth (GIBCO BRL), 5% newborn calf serum (GIBCO BRL), 5% fetal calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, Utah), 100 U of penicillin/ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml (Quality Biological, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.). The cells were incubated at 39°C with 5% CO2. Mouse NIH 3T3 cells and dog D17 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% calf serum (GIBCO BRL), 100 U of penicillin/ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml. The mammalian cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. The plasmid containing pGT-GFP was prepared by using the Qiagen plasmid kit (QIAGEN Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.). Plasmid DNA was introduced into DF-1 cells by calcium phosphate precipitation (18, 36). The transfected cells were passaged two to three times to let the viruses spread throughout the culture. Once virus production peaked, as measured by reverse transcriptase (RT) activity in the culture supernatant (18, 19), the cells were either analyzed as described below or treated with 2.5 μg of mitomycin C/ml (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) to stop cell proliferation. The NIH 3T3 and D17 cells were infected by cocultivation with the virus-producing, growth-arrested DF-1 cells for approximately 48 h.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting and confocal microscope analysis.

Infected DF-1 cells, as well as NIH 3T3 and D17 cells that had been cocultivated with the virus-producing, growth-arrested DF-1 cells, were suspended in 2% fetal calf serum in phosphate-buffered saline at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/ml. The percentage of green cells was measured by a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS). The fluorescent cells were sorted into either a pool or as single cells into a 96-well tissue culture plate. The FACS-sorted cells were cultured either on multiwell Lab-Tek chamber slides (Nalge Nunc, Milwaukee, Wis.) or on glass-bottom microwell dishes (MatTek Corp., Ashland, Mass.). The subcellular localization of the green fluorescence was determined by using either a CLSM Zeiss 310 upright microscope or a CLSM Zeiss 410 inverted microscope.

Identifying the trapped genes.

FACS-sorted NIH 3T3 clones with interesting subcellular localization of green fluorescence were expanded and total RNA was prepared by using RNA STAT-60 reagent (Tel-Test “B”, Inc., Friendswood, Tex.). Poly(A)+ mRNA was isolated from the total RNA by using Oligotex resin (QIAGEN). The genes that were disrupted by the pGT-GFP vector were amplified by using a Marathon cDNA amplification kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.). Briefly, the poly(A)+ mRNA derived from trapped NIH 3T3 cells was converted to double-stranded cDNA. An adapter oligonucleotide was added to the ends of the cDNA to make a library of adapter-ligated cDNA, which was used as the template for 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′ RACE) reactions. The gfp-specific primer for 5′ RACE was ATAGGTGAAGGTAGTGACCAGTGTTGGC; the adapter-specific primer was provided in the kit. The RACE reactions were carried out by using Advantage cDNA PCR kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.). 5′ RACE products were cloned into the TA cloning vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) and sequenced by using ABI PRISM DNA sequencing protocol (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.). The sequences of the RACE products were analyzed by using the BLAST program to search for homologous sequences in the GenBank.

RESULTS

The gene trap vector pGT-GFP (Fig. 1) is an ALSV-based retroviral vector that efficiently infects, but does not replicate in, mammalian cells. pGT-GFP was created by introducing into a derivative of RCASBP-M2C a GFP coding sequence in which the 5′ end of the gfp gene is linked to a splice acceptor and the 3′ end is linked to a modified SV40 polyadenylation signal. To express GFP in cells, the proviral form of the vector must insert into an intron of an actively expressed gene in the appropriate orientation. The splice donor of the cellular gene would be linked to the splice acceptor in the GFP cassette to form a fused transcript with gfp. To obtain valid translation of the fusion transcript, the joining must link the gfp sequence to the cellular gene in the appropriate reading frame. The polyadenylation signal in the gfp gene trap cassette will stop transcription from the fusion gene. Ordinarily such insertions would disrupt the function of the gene into which the vector inserts.

The pGT-GFP vector was tested in DF-1 cells, D17 cells, and NIH 3T3 cells. Virus was prepared in DF-1 cells. The virus-producing DF-1 cells were treated with 2.5 μg of mitomycin C/ml. At this concentration, mitomycin C blocks the proliferation of DF-1 cells but has only a limited effect on virus production (data not shown). D17 and NIH 3T3 cells were infected by cocultivation with mitomycin C-treated, virus-producing DF-1 cells. To determine the percentage of cells that became fluorescent upon viral infection, the cells were analyzed by using a FACS, and the results are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Percentage of cells that became fluorescent upon viral infection

| Cell linea | Vectorb | % of fluorescent cells |

|---|---|---|

| DF-1 | Mock | 0.2 |

| RCASBP-M2C/GFP | 97.4 | |

| pGT-GFP(7) | 2.1 | |

| pGT-GFP(11) | 2.0 | |

| D17 | Mock | 0.3 |

| pGT-GFP(7) | 2.4 | |

| NIH 3T3 | Mock | 0.1 |

| pGT-GFP(7) | 10.7 |

Virally infected DF-1 cells were prepared by passaging transfected cells. NIH 3T3 and D17 cells were infected by cocultivation with the virus-producing, mitomycin C-treated DF-1 cells.

RCASBP-M2C/GFP was used as a positive control that constitutively expresses GFP. pGT-GFP(7) and pGT-GFP(11) are two independent clones of the vector pGT-GFP. NIH 3T3 and D17 cells were cocultivated with different preparations of DF-1 cells that had been separately transfected with pGT-GFP(7).

As negative and positive controls for FACS analysis, mock-infected DF-1 cells and DF-1 cells infected with a virus that constitutively expresses GFP were tested; 0.2% of mock-infected DF-1 cells and 97.4% of infected DF-1 cells were fluorescent, indicating that the FACS analysis was appropriate for this study. About 2% of DF-1 cells infected with pGT-GFP (two preparations of the same vector were tested) were fluorescent at passage three after transfection, and 2.4% of the D17 cells and 10.7% of the NIH 3T3 cells that had been cocultivated with virus-producing, growth-arrested DF-1 cells were fluorescent. Because the D17 cells and NIH 3T3 cells were infected by cocultivation with different preparations of the virus-producing DF-1 cells, the significance of this difference is unclear. In these experiments, the fluorescent cell populations contained some DF-1 cells. Since the DF-1 cells had been treated with mitomycin C, the majority of cells should have been D17 and NIH 3T3 cells, and only these cells should have grown and produced colonies.

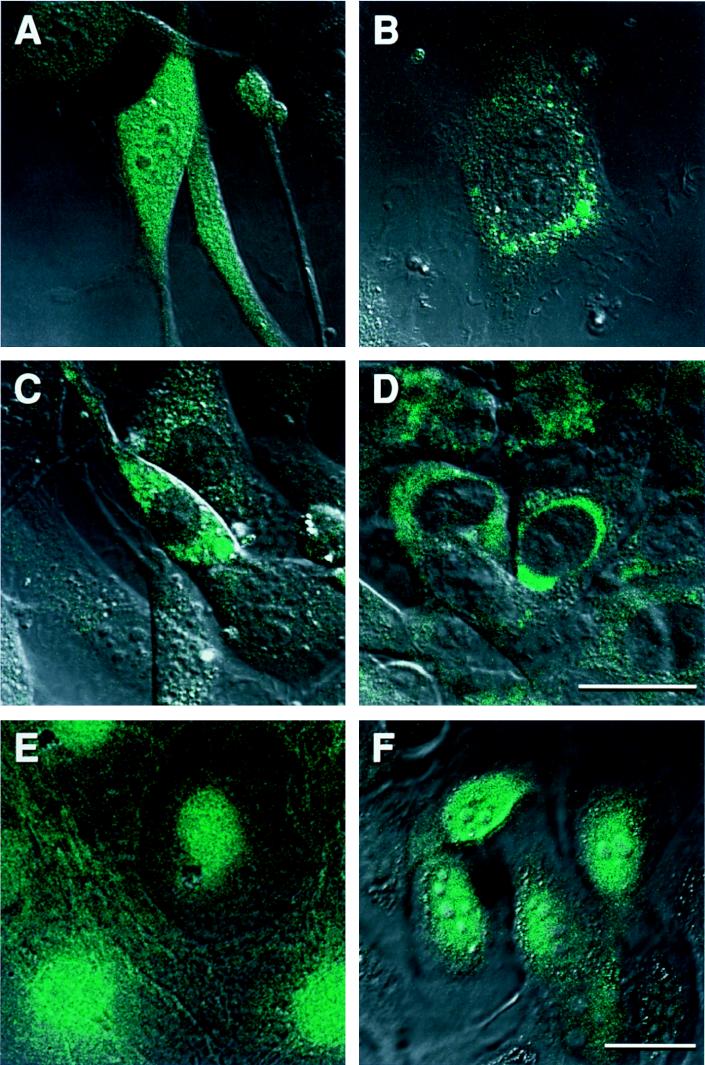

As discussed previously, the subcellular localization of a protein can shed light on its function. GFP is distributed throughout the cell (data not shown). When GFP is linked to a fusion partner, it may adopt a new subcellular location, which is likely determined by the subcellular localization of the cellular gene product included in the fusion. The FACS-sorted green fluorescent NIH 3T3 and D17 cells were observed by using a confocal microscope either as a pool enriched for green fluorescent cells (Fig. 2E and F) or as individual clones (Fig. 2A to D). Of about 90 clones, three patterns of green fluorescence were observed most frequently—general distribution throughout the cell (Fig. 2A), nuclear localization (in some cases excluded from the nucleolus) (Fig. 2E and F), and cytoplasmic localization (Fig. 2C and D). Less frequently observed patterns included small spots in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2B) and a cable-like distribution of GFP inside the cell or on the cell surface (Fig. 2E). The punctate pattern may be caused by the association of the GFP fusion with cellular organelles, such as the Golgi apparatus or the mitochondria. The cable-like GFP pattern may indicate that the fusion protein was a component of the cytoskeleton. The exact location of the GFP can be determined by staining the cells with organelle-specific dyes or by immunostaining the cells with antibody against specific components of the organelles.

FIG. 2.

Different subcellular localizations of GFP fusions observed in living cells by using an inverted confocal microscope. (A to D) Trapped NIH 3T3 lines carrying GT-3, GT-7, GT-12, and GT-13, respectively. (E and F) Trapped D17 cells observed in a cell pool enriched for fluorescent cells. Bar = 25 μm. A to D have the same scale, and E and F have the same scale.

The gfp sequence at the 3′ end of the transcripts produced by the gene fusion can be used as a molecular tag to identify the disrupted gene by using the RACE protocol. 5′ RACE reactions were performed on five FACS-sorted NIH 3T3 clones, which were selected based on their patterns of GFP distribution, some of which are shown in Fig. 2. We failed to obtain a RACE product from one clone; however, we did obtain 5′ RACE amplification products from the four other clones. The results are summarized in Fig. 3.

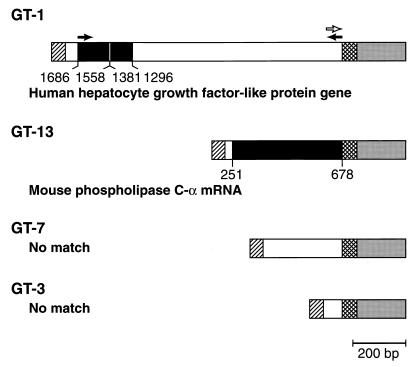

FIG. 3.

Diagram showing the structures of the 5′ RACE products amplified from four different gene trap clones, carrying GT-1, GT-3, GT-7, and GT-13, respectively. Grey box, part of the gfp sequence; cross-hatched box, linker sequence between the cellular gene and gfp; hatched box, the 5′ RACE adapter; open box, trapped chromosomal sequence with no homology in the GenBank; black box, trapped chromosomal sequence with homology in the GenBank; closed arrows, the primers used in RT-PCR; open arrow, the primer used in 3′ RACE reaction. The identities of the trapped cellular genes, with starting and ending positions noted, are labeled. No match, transcripts that have no homologous sequences in GenBank. Bar = 200 bp.

The 5′ RACE products are composed of three regions—the adapter sequence that has been added to the 5′ end of cDNA, the trapped gene sequence joined to the linker sequence at the splice acceptor site, and 197 bp of the GFP coding sequence. BLAST analysis of the nucleotide sequences of the trapped genes GT-3 and GT-7 discovered no sequence homologies in the GenBank, suggesting that these sequences represent segments of novel genes. The trapped genes GT-1 and GT-13 are related to known genes. Cells carrying GT-1 contained green fluorescence that was distributed all over the cell (data not shown, but similar to Fig. 2A). Two fragments of the GT-1 gene share 90 and 82% sequence identity with bp 1296 to 1381 and bp 1558 to 1686 of the human hepatocyte growth-factor-like protein (HLP) gene (GenBank accession no. U37055). The sequences amplified by 5′ RACE reactions should all be transcribed, so it was surprising to find that bp 1296 to 1381 and bp 1558 to 1686 are within the 5′ flanking region of the HLP gene. A simple explanation for this discrepancy is that bp 1296 to 1381 and bp 1558 to 1686 are transcribed through an unknown alternative promoter of the HLP gene. If the two regions are distributed on two adjoining exons, they could be joined in the mature transcript. If this is the case, the remaining approximately 850 bp of sequence that do not have homology to the published sequence of HLP can be interpreted as being unidentified exon(s) of the HLP gene. To test these ideas, we looked for transcription of the GT-1 gene by RT-PCR. A 1,018-bp fragment was amplified from the double-stranded cDNA prepared from cloned cells carrying GT-1, as well as from mouse brain, by using a pair of primers flanking the trapped sequence (data not shown; see Fig. 3 for positions of the primers), thus confirming the expression of this segment into RNA. We cannot tell if the trapped gene uses the same reading frame as gfp in the GT-1 fusion because there is no information in the reading frame of this part of the trapped gene. However, the presence of the green fluorescence in the cells suggested that the GFP coding sequence was translated correctly. The GFP fusion of the clone carrying GT-13 contained sequences from mouse phospholipase C-α (PLC-α) gene (accession no. M73329). The PLC-α gene sequence was joined to gfp at bp 678. The splice acceptor preceding the gfp sequence was used appropriately. Although the 5′ RACE reaction did not reach the 5′ end of the PLC-α gene transcript, the PLC-α gene transcript was in the same reading frame as gfp.

With the sequence information obtained by 5′ RACE, the remaining cDNA sequence of a trapped gene that is downstream of the viral integration site can be obtained by 3′ RACE. As an example, we used 3′ RACE to isolate the 3′ region of the GT-1 gene. The adapter-ligated double-stranded cDNA pools prepared from mouse brain and cloned cells carrying GT-1 were used as 3′ RACE templates. The adapters had been added to both 5′ and 3′ ends of the cDNA, so that the same adapter-ligated cDNA pool could be used for either 5′ or 3′ RACE. A gene-specific primer complementary to the 3′ end of the trapped GT-1 sequence was paired with the primer complementary to the 3′ RACE adapter reactions (see Fig. 3 for position of the GT-1 primer). A 3.8-kb fragment was amplified from both mouse brain cDNA and from cDNA derived from cells carrying GT-1 (data not shown). This fragment contained the transcript of the undisrupted GT-1 gene extending from the GT-1-specific primer towards the end of the transcript. The 3.8-kb fragment was amplified from the cDNA made from cells carrying GT-1 because the viral insertion is heterozygous in those cells; one allele of the gene contained the proviral insertion, the other allele was wild type. A 1.1-kb fragment was amplified from the cDNA derived from cells carrying GT-1 but not from the mouse brain cDNA, suggesting that this fragment was from the gfp fusion transcript. Sequencing of the 1.1-kb fragment confirmed that the disrupted allele of the GT-1 gene contained the gfp gene sequence.

DISCUSSION

The gene trap vector pGT-GFP is an ALSV-based retroviral vector with the env gene from the amphotropic MLV. The proviral form of pGT-GFP is able to insert into the mammalian genome without causing gross rearrangement. Compared with an MLV-based gene trap vector, the proviral form of which may be mobilized due to recombination or complementation with endogenous viruses, the integrated pGT-GFP is stable in mammalian cells. The lack of homologous sequences in the mammalian genome makes it easy to detect pGT-GFP proviral DNA in mammalian cells. Another useful feature of the pGT-GFP vector is its reporter gene gfp, which provides a vital and dynamic marker that can be used to visualize gene expression in the living cell and animal. Unlike other markers, no prior fixation and staining are required to view GFP, nor are immunostaining procedures necessary when a more precise localization of the marker in cell is desired. However, it must be kept in mind that, although the GFP marker used in our study works well in tissue culture systems, a modified version of GFP may be necessary to follow gene expression in embryo and adult mice (13, 27, 39, 40).

The appropriate integration of pGT-GFP into an actively expressed gene will produce a gene fusion between the cellular gene and gfp. If the resulting fusion transcript is in frame, the cells should express a fusion protein. The subcellular locations of the GFP fusions will reflect the distribution of the trapped cellular gene products and provide a parameter to preselect the trapped cells before additional efforts are made to clone the cellular genes and to generate chimeric mice.

The data obtained from infecting DF-1, D17, and NIH 3T3 cells demonstrated that pGT-GFP was able to generate useful GFP fusions. The percentage of green fluorescent cells obtained after infection varied for different cell lines: about 2% for DF-1 and D17 cells and 10% for NIH 3T3 cells. We do not know whether this difference is significant or not. As has already been discussed, integration of pGT-GFP in the mammalian genome has to meet several criteria in order to make a GFP fusion: the provirus needs to be inserted in the intron of an actively transcribed gene, the orientation of gfp has to be the same as the cellular gene, and splicing of the transcript has to generate a valid reading frame for gfp. Therefore, it seems reasonable that a relatively small percentage of cells would be fluorescent. It should be clear that the vector we have developed requires the fusion to be in one of three possible reading frames. This means that the use of this vector will result in some genes being missed. Additional gene trap vectors closely related to pGT-GFP that contain gfp in the other two reading frames can be made. The use of all three vectors will increase the chance that any given gene will be trapped.

The FACS-sorted fluorescent cells were selected based on their pattern of fluorescence. Transcripts from the disrupted cellular genes were cloned by using 5′ RACE. In experiments done with NIH 3T3 cells, we identified four genes: one known gene, two novel genes, and one gene that contained sequences from a known gene but also sequences that have no homology in the GenBank. The expression of the novel sequences of the GT-1 gene was confirmed by RT-PCR. The 3′ region of the wild-type allele of the GT-1 gene that is downstream of the proviral integration was identified by using 3′ RACE.

Several gene trap protocols have been developed in which the trapped cells were selected based on the distribution of the fusion reporter protein in the cell. One such protocol enriched and selected for membrane proteins and secreted proteins (32); another protocol focused on nuclear proteins (33). For such gene trap experiments, including ours, there is always the possibility that the signals that are crucial for protein localization, such as nuclear localization signal and signal peptide, may not be included in a particular gene fusion. Thus, the distribution of the reporter fusion may not always reflect the intrinsic distribution of the endogenous protein. However, there are data to suggest that when a protein fusion has a specific subcellular distribution, this distribution is similar to that of the normal cellular protein (21, 26, 33). Our data, while limited, support this conclusion. For cells carrying GT-13, the PLC-α:GFP fusion protein was cytoplasmic, concentrated primarily in the perinuclear region (Fig. 2D). This distribution agreed with the observation that PLC-α protein was a soluble protein primarily in the cytosol (17). However, while the PLC-α:GFP fusion does not appear to be in the cytoplasmic membrane, PLC-α protein was also detected in the membrane fraction (23, 35). The discrepancies between the subcellular distributions of the GFP fusion and the normal cellular protein may be explained by the differences in cell types used in different studies. Alternatively, if the pGT-GFP integration is too close to the 5′ end of the trapped gene, the protein localization signals that are present in the normal protein could be absent in the GFP fusions.

If multiple proviral integrations are present in a cell, is the gene identified by 5′ RACE always the gene that produces the GFP fusion? Since the trapping is effective for 2 to 10% of the cells, it is unlikely that a single cell would contain more than one integration that makes a GFP fusion protein. A Southern blot can be used to determine the number of proviral insertions per cell.

To try to answer questions about the number of proviruses present in each cell, parallel experiments were done by using related ASLV-based vectors with an amphotropic MLV envelope that contains a selectable marker (either puromycin resistance or neomycin resistance) under the control of an internal promoter. Murine ES cells were infected by cocultivation with mitomycin-C-treated DF-1 cells (see Materials and Methods). Approximately 20% of the ES cells were infected, judged by PCR analyses of randomly picked clones. About one-third of the infected cells could be selected by using the appropriate selective agent (puromycin or G418). Southern transfer analysis of DNA from individual drug-resistant clones showed that the number of proviruses varied from one to six (data not shown). Since these clones were resistant, they presumably had a higher average provirus copy number than did the clones that contained proviruses that were not expressed. An average copy number of two to four proviruses per infected cell is probably acceptable for most gene trapping experiments. We believe that a shorter cocultivation period would reduce the average provirus copy number if this were necessary for some particular experiment.

Although it is probably a rare event, the green fluorescence we observed in some clones might be caused by the expression of unfused GFP protein driven by a nearby cellular promoter. The ATG initiation codon was not removed from the GFP coding region in vector pGT-GFP, thus the GFP coding sequence could be expressed as a promoter fusion as well as a gene fusion. In such cases, the green fluorescence should not be localized within the cell, and the sequences amplified by 5′ RACE should identify transcribed but untranslated regions of a gene.

The trapping experiments with pGT-GFP performed in mouse NIH 3T3 cells and dog D17 cells suggested that pGT-GFP could be used to trap genes in mouse ES cells. Once a cell containing a fusion with an interesting subcellular expression pattern is chosen and the disrupted gene is identified, the phenotype of the insertional mutation can be assessed by generating and analyzing mutant mice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Douglas Foster for providing DF-1 cells, James Resau and Eric Hudson for confocal microscope studies, Marilyn Powers for DNA sequencing, Louise Finch and her group for FACS analysis, and Hilda Marusiodis for formatting the manuscript.

Research was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, DHHS, under contract with ABL.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amsterdam A, Lin S, Hopkins N. The Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein can be used as a reporter in live zebrafish embryos. Dev Biol. 1995;171:123–129. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amsterdam A, Lin S, Moss L G, Hopkins N. Requirements for green fluorescent protein detection in transgenic zebrafish embryos. Gene. 1996;173:99–103. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00719-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Astrin S M, Buss E G, Hayward W S. Endogenous viral genes are non-essential in the chicken. Nature. 1979;282:339–341. doi: 10.1038/282339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker R K, Haendel M A, Swanson B J, Shambaugh J C, Micales B K, Lyons G E. In vitro preselection of gene-trapped embryonic stem cell clones for characterizing novel developmentally regulated genes in the mouse. Dev Biol. 1997;185:201–214. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barsov E V, Hughes S H. Gene transfer into mammalian cells by a Rous sarcoma virus-based retroviral vector with the host range of the amphotropic murine leukemia virus. J Virol. 1996;70:3922–3929. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3922-3929.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barthmaier P, Fyrberg E. Monitoring development and pathology of Drosophila indirect flight muscles using green fluorescent protein. Dev Biol. 1995;169:770–774. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bates P, Young J A, Varmus H E. A receptor for subgroup A Rous sarcoma virus is related to the low density lipoprotein receptor. Cell. 1993;74:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90726-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns N, Grimwade B, Ross-Macdonald P B, Choi E Y, Finberg K, Roeder G S, Snyder M. Large-scale analysis of gene expression, protein localization, and gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1087–1105. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward W W, Prasher D C. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Federspiel M J, Bates P, Young J A, Varmus H E, Hughes S H. A system for tissue-specific gene targeting: transgenic mice susceptible to subgroup A avian leukosis virus-based retroviral vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11241–11245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Federspiel M J, Hughes S H. Effects of the gag region on genome stability: avian retroviral vectors that contain sequences from the Bryan strain of Rous sarcoma virus. Virology. 1994;203:211–220. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Federspiel M J, Swing D A, Eagleson B, Reid S W, Hughes S H. Expression of transduced genes in mice generated by infecting blastocysts with avian leukosis virus-based retroviral vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4931–4936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Godwin A R, Stadler H S, Nakamura K, Capecchi M R. Detection of targeted GFP-Hox gene fusions during mouse embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13042–13047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenhouse J J, Petropoulos C J, Crittenden L B, Hughes S H. Helper-independent retrovirus vectors with Rous-associated virus type O long terminal repeats. J Virol. 1988;62:4809–4812. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4809-4812.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higashijima S, Okamoto H, Ueno N, Hotta Y, Eguchi G. High-frequency generation of transgenic zebrafish which reliably express GFP in whole muscles or the whole body by using promoters of zebrafish origin. Dev Biol. 1997;192:289–299. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Himly M, Foster D N, Bottoli I, Iacovoni J S, Vogt P K. The DF-1 chicken fibroblast cell line: transformation induced by diverse oncogenes and cell death resulting from infection by avian leukosis viruses. Virology. 1998;248:295–304. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofmann S L, Majerus P W. Identification and properties of two distinct phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C enzymes from sheep seminal vesicular glands. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:6461–6469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes S, Kosik E. Mutagenesis of the region between env and src of the SR-A strain of Rous sarcoma virus for the purpose of constructing helper-independent vectors. Virology. 1984;136:89–99. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes S H, Greenhouse J J, Petropoulos C J, Sutrave P. Adaptor plasmids simplify the insertion of foreign DNA into helper-independent retroviral vectors. J Virol. 1987;61:3004–3012. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3004-3012.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joyner A L, Skarnes W C, Rossant J. Production of a mutation in mouse En-2 gene by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1989;338:153–156. doi: 10.1038/338153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leonhardt H, Page A W, Weier H U, Bestor T H. A targeting sequence directs DNA methyltransferase to sites of DNA replication in mammalian nuclei. Cell. 1992;71:865–873. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90561-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long Q, Meng A, Wang H, Jessen J R, Farrell M J, Lin S. GATA-1 expression pattern can be recapitulated in living transgenic zebrafish using GFP reporter gene. Development (Camb) 1997;124:4105–4111. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.4105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mah S J, Ades A M, Mir R, Siemens I R, Williamson J R, Fluharty S J. Association of solubilized angiotensin II receptors with phospholipase C-alpha in murine neuroblastoma NIE-115 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;42:217–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meng A, Tang H, Ong B A, Farrell M J, Lin S. Promoter analysis in living zebrafish embryos identifies a cis-acting motif required for neuronal expression of GATA-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6267–6272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller D A. Development and applications of retroviral vectors. In: Coffin J M, Hughes S H, Varmus H E, editors. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 437–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nan X, Tate P, Li E, Bird A. DNA methylation specifies chromosomal localization of MeCP2. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:414–421. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okabe M, Ikawa M, Kominami K, Nakanishi T, Nishimune Y. ‘Green mice’ as a source of ubiquitous green cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;407:313–319. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petropoulos C J, Hughes S H. Replication-competent retrovirus vectors for the transfer and expression of gene cassettes in avian cells. J Virol. 1991;65:3728–3737. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3728-3737.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaefer-Klein J, Givol I, Barsov E V, Whitcomb J M, VanBrocklin M, Foster D N, Federspiel M J, Hughes S H. The EV-O-derived cell line DF-1 supports the efficient replication of avian leukosis-sarcoma viruses and vectors. Virology. 1998;248:305–311. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scherer C A, Chen J, Nachabeh A, Hopkins N, Ruley H E. Transcriptional specificity of the pluripotent embryonic stem cell. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:1393–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skarnes W C, Auerbach B A, Joyner A L. A gene trap approach in mouse embryonic stem cells: the lacZ reported is activated by splicing, reflects endogenous gene expression, and is mutagenic in mice. Genes Dev. 1992;6:903–918. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.6.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skarnes W C, Moss J E, Hurtley S M, Beddington R S. Capturing genes encoding membrane and secreted proteins important for mouse development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6592–6596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tate P, Lee M, Tweedie S, Skarnes W C, Bickmore W A. Capturing novel mouse genes encoding chromosomal and other nuclear proteins. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2575–2585. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.17.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Timmons L, Becker J, Barthmaier P, Fyrberg C, Shearn A, Fyrberg E. Green fluorescent protein/beta-galactosidase double reporters for visualizing Drosophila gene expression patterns. Dev Genet. 1997;20:338–347. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1997)20:4<338::AID-DVG5>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wakui H, Komatsuda A, Ishino T, Imai H, Kobayashi R, Nakamoto Y, Miura A B. Localization of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C-alpha in porcine kidney. Kidney Int. 1992;42:888–895. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wigler M, Pellicer A, Silverstein S, Axel R, Urlaub G, Chasin L. DNA-mediated transfer of the adenine phosphoribosyltransferase locus into mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1373–1376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeh E, Gustafson K, Boulianne G L. Green fluorescent protein as a vital marker and reporter of gene expression in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7036–7040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zambrowicz B P, Friedrich G A, Buxton E C, Lilleberg S L, Person C, Sands A T. Disruption and sequence identification of 2,000 genes in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1998;392:608–611. doi: 10.1038/33423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zernicka-Goetz M, Pines J, McLean Hunter S, Dixon J P, Siemering K R, Haseloff J, Evans M J. Following cell fate in the living mouse embryo. Development (Camb) 1997;124:1133–1137. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.6.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhuo L, Sun B, Zhang C L, Fine A, Chiu S Y, Messing A. Live astrocytes visualized by green fluorescent protein in transgenic mice. Dev Biol. 1997;187:36–42. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]