Abstract

Objective

Bariatric surgery is an effective treatment to obesity, leading to weight loss and improvement in glycemia, that is characterized by hypersecretion of gastrointestinal hormones. However, weight regain and relapse of hyperglycemia are not uncommon. We set to identify mechanisms that can enhance gastrointestinal hormonal secretion following surgery to sustain weight loss.

Methods

We investigated the effect of somatostatin (Sst) inhibition on the outcomes of bariatric surgery using a mouse model of sleeve gastrectomy (SG).

Results

Sst knockout (sst-ko) mice fed with a calorie-rich diet gained weight normally and had a mild favorable metabolic phenotype compared to heterozygous sibling controls, including elevated plasma levels of GLP-1. Mathematical modeling of the feedback inhibition between Sst and GLP-1 showed that Sst exerts its maximal effect on GLP-1 under conditions of high hormonal stimulation, such as following SG. Obese sst-ko mice that underwent SG had higher levels of GLP-1 compared with heterozygous SG-operated controls. The SG-sst-ko mice regained less weight than controls and maintained lower glycemia months after surgery. Obese wild-type mice that underwent SG and were treated daily with a Sst receptor inhibitor for two months had higher GLP-1 levels, regained less weight, and improved metabolic profile compared to saline-treated SG-operated controls, and compared to inhibitor or saline-treated sham-operated obese mice.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that inhibition of Sst signaling enhances the long-term favorable metabolic outcomes of bariatric surgery.

Keywords: Sleeve gastrectomy, Somatostatin, GLP-1, Mathematical model, Bariatric surgery

Highlights

-

•

Obese somatostatin knockout mice have low glycemia and elevated fasting GLP-1 levels.

-

•

Somatostatin knockout mice have lower weight and higher GLP-1 compared to heterozygous siblings after sleeve gastrectomy.

-

•

Inhibition of somatostatin receptors enhance the metabolic outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy in wild-type obese mice.

1. Introduction

Somatostatin (Sst) is a neuropeptide and hormone expressed by numerous endocrine and neural cell types that signals through five receptors. Sst is a negative regulator of neural activity, of both exocrine and endocrine secretion, and of cell proliferation in some cases [1]. Sst secreted from the hypothalamus suppresses growth hormone (GH) secretion from the anterior pituitary gland [2]; Sst secreted by delta cells in the endocrine pancreas inhibits insulin and glucagon secretion through paracrine and endocrine signaling [3,4]. Similarly, Sst secreted by delta cells in the stomach, intestine, and colon reduces the secretion of virtually all gastrointestinal (GI) hormones and inhibits acid secretion from gastric parietal cells [5,6]. In the clinic, Sst analogs are used to treat acromegaly, dumping syndrome, and some types of neuroendocrine tumors [7].

Despite the wide distribution of Sst-secreting cells and their effects on many organs and systems, Sst knockout mice (sst-ko) have a relatively mild phenotype. sst-ko mice display altered GH secretion patterns and higher levels of GH but are not larger than wild-type mice [8]. Rather, male sst-ko mice have a feminized hepatic gene expression [9]. sst-ko mice exhibit hypergastrinemia, and their stomach has more parietal cells, secretes more acid, and has more proliferating cells [10].

Sst deficiency is associated with lower glucose levels, especially in neonate mice [4,11,12]. In vitro, islets of adult sst-ko mice have a higher basal and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion rate and secrete glucagon in response to high glucose [13]. Adult sst-ko mice were reported to have lower glycemia but did not display hyperinsulinemia [14,15]. Inhibition of Sst Receptor 2 or Sst Receptor 5, expressed in the murine intestinal L-cells, improved glucose tolerance due to GLP-1 hypersecretion [16].

Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) is a common bariatric surgery wherein most of the stomach is excised along the greater curvature to produce a sleeve-shaped stomach. This surgery leads to weight loss improved glycemic control, and alleviation of metabolic disorders in most patients and rodent models [[17], [18], [19], [20]]. SG affects the microbiome, the levels of bile acids and other metabolites in the blood, and leads to a post-prandial increase in GI and pancreatic hormones such as GLP-1 and insulin and modulates processes that regulate systemic metabolism [[21], [22], [23]]. SG affects gastric emptying and intestinal motility [24], and in some cases causes dumping syndrome [25,26], which can be treated by Sst analogs [27]. The effects of SG may wane over time, and weight regain and relapse of hyperglycemia and other metabolic diseases are not uncommon [28].

In this study, we aimed to test the role of Sst in the context of obesity and SG. We found that obese sst-ko mice had a superior long-term response to SG compared to their heterozygous siblings. Pharmacological inhibition of Sst Receptors in obese mice enhanced the long-term metabolic outcomes of SG. These improvements were associated with higher levels of GLP-1 in the plasma.

2. Results

2.1. Sst knockout mice gain weight normally but display better glycemic control following a high-fat high-sucrose diet

Male sst-ko mice and their heterozygous male siblings were fed a high-fat high-sucrose (HFHS) diet for 110 days. Genotype did not affect weight gain, and both groups became obese (Figures 1A, S1A). By the end of the experiment, sst-ko mice had higher fat mass and lower lean mass than littermate controls (Figure 1B–C) – with no difference in weight. There was no difference in plasma triglycerides or cholesterol in sst-ko mice and their siblings (Figure S1B–C). The livers of sst-ko mice had a lower degree of hepatic steatosis, higher glycogen content, and higher expression of genes characterizing female mice liver (Figures 1D–G, S1D). These results are overall consistent with previous studies characterizing sst-ko mice [8,9].

Figure 1.

Metabolic characterization of sst-ko mice following a calorie-rich diet. A. Weight gain in male sst-ko mice (red) and their male heterozygous siblings (black) during high-fat high-sucrose feeding. n = 6,8. No significant difference between the groups by 2-way continuous measurement ANOVA. B–C. Fat (B) and lean mass (C) of sst-ko mice and heterozygous siblings. D–F. Percent of lipid area in hepatic H&E stains of sst-ko and heterozygous siblings (D). A representative hematoxylin and eosin image of the liver of an sst-ko mouse is shown in (E) and of a heterozygous mouse in (F). Scale bar = 100 μm for E,F. G. Glycogen content in the livers of sst-ko and heterozygous siblings. ∗,∗∗p < 0.05, p < 0.01 using Student's t-test (B–D,G). Error bars in A denote the standard error of the mean (SEM).

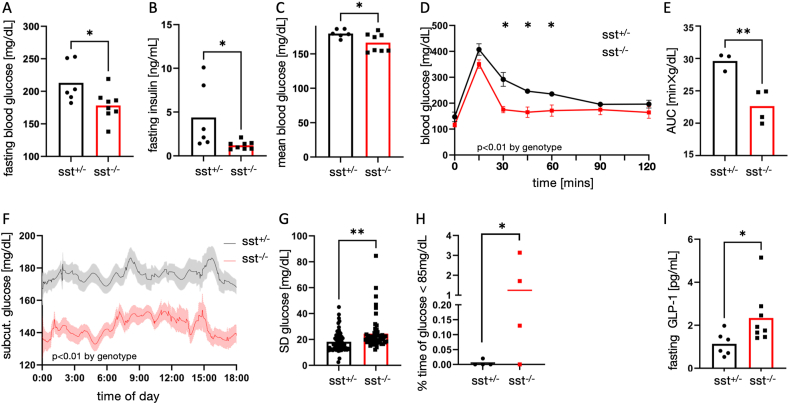

We found that sst-ko mice had lower fasting and average glucose levels, lower fasting insulin, and responded better to an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). (Figure 2A–E). To gain better insight into the glycemia of sst-ko mice, we implanted a continuous glucose measurement device on sst-ko mice and sibling controls fed on an HFHS diet and followed their glycemia for a week [29]. Data showed a reduction in mean glucose levels and higher variability of glucose levels in sst-ko mice (Figure 2F–H). Mild hypoglycemia, defined as non-fasting glucose <85 mg/dL was observed in sst-ko mice. Fasting GLP-1 levels increased in the plasma of sst-ko mice compared with heterozygous siblings (Figure 2I).

Figure 2.

Glycemia of sst-ko mice following a calorie-rich diet. A. Fasting blood glucose levels of sst-ko mice (red) and their heterozygous siblings (black). B. Fasting plasma insulin levels of sst-ko mice and their heterozygous siblings. C. Average non-fasting plasma glucose levels of sst-ko mice and their heterozygous siblings. D,E. Plasma glucose levels (D) and area under the curve (E) of sst-ko mice and their heterozygous siblings following an oral glucose tolerance test. n = 3,4. F. Average glucose levels measured using a continuous glucose monitor device. Shades show SEM. n = 4,4. G,H. Standard deviation in glucose levels measured by a continuous glucose monitor device. Each dot represents one day in one mouse. H. The percentage of time in which glucose was lower than 85 mg/dL was measured by a continuous glucose monitor device. I. Fasting plasma GLP-1 levels in sst-ko mice and their heterozygous siblings. ∗,∗∗p < 0.05, p < 0.01 using Student's t-test (A–C, E,I) and Welch's t-test (H). p < 0.01 by genotype in a 2-way repeated measurement ANOVA in D,F,G. ∗p < 0.05 in D,G by Tukey post-hoc test. Error bars in D and the shaded area in F denote SEM.

2.2. A mathematical model for the regulation of GLP-1 secretion by Sst

The mild metabolic phenotype of sst-ko mice prompted us to identify conditions in which Sst inhibition may have a more pronounced effect. GLP-1 and Sst form a negative feedback loop wherein GLP-1 increases Sst secretion, and Sst inhibits GLP-1 and Sst secretion directly (Figure 3A) [16,30,31]. We modeled the GLP-1-Sst feedback to gain further insight into their interaction. Analytical approximations and simulations show that the effect of Sst is strongest in terms of absolute difference in GLP-1 secretion and in fold-change in GLP-1 secretion when the stimulant level is highest. A strong stimulation will elicit a high Sst signal, which is amplified by the high levels of GLP-1, limiting the overall increase in GLP-1. In the absence of Sst, the same stimulant will lead to a much higher GLP-1 secretion. (Figures 3B, S2A, B, SI text). This topology is similar to the delta and beta-cell topology of the pancreas.

Figure 3.

Long-term response of obese sst-ko mice to sleeve gastrectomy. A. A diagram describing the interaction between a stimulant, GLP-1 and Sst. B. Simulation of the difference in GLP-1 level in sst-ko mice and wild-type mice as a function of the hormonal stimulation according to the mathematical model. GLP-1 and stimulant levels in arbitrary units. C. Change in weight of male SG-sst-ko mice (SG-sst−/−, orange), and male SG-het siblings (SG-sst+/−, black) following surgery. n = 8,9. p < 0.01 by genotype by continuous measures 2-way ANOVA. D. Average glucose levels of SG-sst-ko mice and SG-het siblings. Each dot represents the average non-fasting glucose levels of a single mouse after surgery. E,F. Blood glucose levels (E) and area under the curve (F) of sst-ko mice and their heterozygous siblings during an oral glucose tolerance test performed 6 weeks after surgery. There were no differences in AUC or by strain in continuous measures 2-way ANOVA. G. Fasting plasma insulin levels. H,I. Fasting (H) and 15 min postprandial (I) plasma glucagon levels. J,K. Fasting (J) and 15 min postprandial (K) plasma Glp-1 levels. ∗,∗∗,∗∗∗p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001 using Student's t-test (D,F–J) and Welch's t-test (K). 2-Way repeated measurement ANOVA and ∗p < 0.05 by Tukey post-hoc test (C,E). Error bars in C,E denote SEM.

The extent of GLP-1 inhibition by Sst depends on model parameters and was chosen to be mild to allow a monotonous increase in GLP-1 as a function of stimulant level. The assumption that the stimulant induces Sst secretion, and that Sst auto-inhibits its secretion can be relaxed, leading to similar qualitative results. However, previous studies and single-cell gene expression atlases have shown that gastrointestinal delta cells express somatostatin receptors and luminal transporters [[32], [33], [34]].

2.3. Sst-ko mice have superior metabolic outcomes following sleeve gastrectomy

SG was shown by us and many other groups to increase the secretion of GLP-1 as well as other anorexigenic gut hormones in rodents [22,35]. Based on our mathematical model, we hypothesized that this increase occurs despite strong inhibition by Sst, and therefore SG in sst-ko mice will lead to an even greater secretion of GLP-1, and affect the overall outcomes of surgery.

To test this hypothesis, male sst-ko mice and heterozygous littermate controls were fed an HFHS diet for 12 weeks and underwent SG. Mice were kept on the HFHS diet for 90 more days. There was no difference in post-surgical mortality between the strains. 2 months after surgery and onwards, SG-sst-ko mice regained less weight than SG-het controls (Figures 3C, S2C). SG-sst-ko mice had lower average blood glucose levels. (Figures 3D, S2D). SG-sst-ko mice had higher blood glucose levels 15 min after oral glucose gavage but had the same glucose tolerance as SG-het controls (Figure 3E–F). Both sst-ko and controls had low-grade hepatic steatosis after SG despite the prolonged HFHS diet and a similar plasma lipid profile (Figure S2E–G). Hormonally, SG-sst-ko mice had lower fasting insulin and higher post-prandial glucagon levels (Figure 3G–I). SG-sst-ko had 3-fold higher post-prandial levels of GLP-1, in agreement with the model, displaying a mean difference of nearly 40 pg/mL (Figure 3J–K).

2.4. Pharmacological inhibition of somatostatin receptors improves metabolic outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy

The improved metabolic outcomes of SG in sst-ko mice could be a result of the different physiology of these mice before surgery which makes surgery more effective, a result of a modified response to SG, or both. To isolate the role of Sst after surgery, we used a pharmacological inhibitor of Sst signaling after SG. C57Bl6 male mice were fed an HFHS for 11 weeks and then underwent SG or sham surgery. Mice remained on a HFHS diet, and after one week, each surgical group was weight matched and randomized into two sub-groups that received daily subcutaneous injections of cyclosomatostatin (cSst), a pan-Sst receptor inhibitor, or saline [36].

SG-operated mice weighed less and displayed an altered glycemic response to a mixed-meal tolerance test: lower fasting glucose levels, higher glucose levels 15 min after gavage of the mixed meal, and lower blood glucose levels afterwards (Figures 4A–D, S3A). SG-operated mice had higher fasting insulin levels and post-prandial GLP-1 levels, lower total cholesterol, LDL and HDL levels with no significant difference in triglyceride levels, and a lower degree of hepatic steatosis (Figures 4E–H, S3B). cSst treatment by itself did not have a significant effect on any outcome.

Figure 4.

Long-term response of obese mice to SG followed by inhibition of somatostatin signaling. A. Change in weight of SG-cSst mice (purple triangles) and SG-saline mice (black triangles), sham-cSst mice (green circles) and sham-saline mice (black squares). p < 0.01 by treatment and by treatment × surgery interaction by 3-way repeated measurement ANOVA. Error bars denote SEM. n = 7,7,9,9. B. Glucose levels following an oral mixed meal tolerance test. Colors as in A. p < 0.01 by treatment 3-way repeated measurement ANOVA. Error bars denote SEM. n = 7,7,9,9. C. Area under the curve (AUC) for the mixed meals tolerance test. D. Fasting plasma insulin levels at the end of the experiment. E,F. Fasting (E) and post-prandial (F) plasma GLP-1 levels at the end of the experiment. G. Post-prandial total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, and LDL-cholesterol in the plasma at the end of the experiment. H. Quantification of hepatic steatosis by percent of the area covered by lipid droplets in a hematoxylin and eosin staining. ∗,∗∗p < 0.05, p < 0.01 by Tukey post-hoc test (A,F,G,H). ##p < 0.01 by surgery in 2-way ANOVA.

When comparing cSst to saline-treated SG-operated mice, we observed that cSst-treated SG-operated mice (cSst-SG mice) had lesser weight regain than saline-treated SG-operated mice (saline-SG) starting from 8 weeks after surgery (Figures 4A, S3A). cSst-SG mice had higher post-prandial GLP-1 levels, and lower plasma lipid levels than saline-SG mice (Figure 4E–H). There were no differences in glycemia, fasting plasma c-peptide, or glucagon levels or intestinal velocity between cSst-SG and saline-SG mice (Figures 4B–D, S3C–F). cSst had no effects on the sham-operated mice in any parameter tested. A principal components analysis on the experimental outcomes demonstrated the differences between SG and sham-operated mice, and the stronger metabolic effect of cSST-SG operated mice compared with saline-SG-operated mice (Figure S3G).

3. Discussion

The metabolic phenotype of sst-ko mice is surprisingly mild, given the wide distribution of Sst and its receptors in neurons, endocrine and exocrine cells [8]. Using mathematical modeling, we hypothesized that sst-ko mice would present with a stronger phenotype in conditions where Sst-regulated endocrine cells receive strong secretion stimuli. SG leads to the hypersecretion of many GI and pancreatic hormones that are regulated by Sst [[21], [22], [23]]. Indeed, obese SG-operated sst-ko mice and obese SG-operated mice treated with a Sst-receptor inhibitor displayed higher GLP-1 levels and lower weight regain months after SG.

3.1. sst-ko mice have a mild metabolic phenotype

sst-ko mice gained weight at the same rate as their co-caged heterozygous siblings, but their fat mass was higher, and their lean mass was lower. At the same time, sst-ko mice had lower-grade hepatic steatosis and higher hepatic glycogen content, suggestive of greater utilization of hepatic fatty acids, or higher lipid export from the liver to adipose tissue. These observations can be explained in part by the reported differences in GH signaling in sst-ko mice, which affect lipid distribution, hepatic metabolism and gene expression, and lean mass [5,8,37].

We characterized the differences in glycemia between sst-ko mice and heterozygous siblings using a CGM device. sst-ko mice had lower average glycemia and a wider distribution of glucose levels. These observations are in line with the role of Sst in repressing insulin and glucagon secretion and limiting hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia [12,15]. We noted that most sst-ko mice had non-fasting glycemia of less than 85 mg/dL even after a prolonged HFHS diet over 1% of the time, while heterozygous siblings did not reach these low glucose levels. The lower fasting insulin levels in sst-ko mice are counter-intuitive but can be a result of increased hepatic insulin clearance in obese sst-ko mice and higher hepatic insulin sensitivity which are correlated with the observed lower degree of hepatic steatosis, and lower glycemia [18]. sst-ko mice displayed an increase in fasting GLP-1 levels, consistent with a tonic inhibition of GLP-1 by Sst [31].

3.2. sst-ko mice have a better long-term response to sleeve gastrectomy

We compared the long-term response of SG in male sst-ko mice and their heterozygous siblings. To the best of our knowledge, sst+/− mice do not have a metabolic phenotype, and the more conservative comparison of the full knockout to the co-caged heterozygous siblings diminishes potential maternal, housing or strain-specific experimental artifacts.

GLP-1 and Sst form a negative feedback loop wherein GLP-1 induces or enhances Sst secretion, while Sst inhibits GLP-1 secretion [16,31]. A similar feedback topology exists between insulin and Sst, although in this case, pancreatic beta cells secrete UCN3 to enhance Sst secretion [38]. Mathematical modeling showed that in conditions of high stimulation of hormone secretion, such as following SG, the negative feedback between a hormone and Sst would have a more pronounced effect.

Based on published data, we assumed that luminal signals induce both GLP-1 and Sst secretion and that GLP-1 amplified Sst secretion [16,31] (SI text). In accordance with the model, post-prandial GLP-1 with further increased in sst-ko mice. Post-prandial plasma levels of Sst were higher following SG in rat [39], in agreement with our model. However, it is difficult to assess intestinal Sst secretion after SG by Sst plasma levels due to the wide distribution of Sst-expressing cells in the gastrointestinal and neural systems, and their often paracrine mode of action [21,23,40].

SG increases glucagon levels, particularly in rodent models [18]. Post-prandial glucagon was elevated in SG-operated sst-ko mice compared with heterozygous controls and also compared with fasting glucagon levels in SG-sst-ko mice. High glucose stimulates glucagon secretion from islets isolated from sst-ko mice, implying that Sst secreted from pancreatic delta cells represses glucagon secretion in response to high glucose [13]. The high post-prandial levels of glucagon in SG-sst-ko mice may reflect a failure of glucagon secretion inhibition in high glucose levels in this genotype.

3.3. cSst-treated mice show better long-term response to sleeve gastrectomy

Alternative explanations for the favorable metabolic parameters of SG-sst-ko mice compared with heterozygous siblings are the prior lower insulin and glucose levels and different fat distribution of obese sst-ko and heterozygous siblings. We used cSst [36], a pan-Sst receptor inhibitor in mice of the same background strain as the sst-ko mice to control for pre-existing differences between sst-ko mice and their heterozygous siblings. By randomizing the mice into cSst- or saline-treated mice a week after SG, we also controlled for differences in the early response to surgery.

cSst-SG mice maintained a greater weight loss and had better glycemia than saline-SG controls, in agreement with the results from the genetic model. They had similar levels of insulin and glucagon, and similar low-grade hepatic steatosis, yet displayed higher levels of plasma GLP-1. These results support a role for post-surgical Sst signaling in regulating the long-term outcomes of SG. cSst did not affect sham-operated mice compared to saline-treated sham-operated mice, highlighting the importance of SG in exposing the effects of Sst receptor inhibition.

Weight regain following SG is common in patients and mice models. Saline-treated SG-operated were 2–3 g leaner than sham-operated controls treated with either saline or cSst. cSst-treated SG-operated mice were 6 g leaner than sham-operated mice, demonstrating the effect of cSst on top of SG for maintaining long-term weight loss. This synergistic effect was observed also in the cholesterol profile, and GLP-1 levels, which were highest in the cSst-treated SG-operated mice. While sst-ko mice had the same weight and lower glycemia compared to heterozygous siblings, the main effect of SG in sst-ko mice and cSst-treated mice compared to controls was on weight and not glycemia. We hypothesize that SG decreases glycemia to such an extent that the differences between genotypes, which are more subtle were not apparent without using a CGM. The effects on weight regulation were more pronounced.

There are important differences between the experiments comparing the genetic and pharmacologic inhibition of Sst signaling after SG. These differences can be explained by the effect of daily injections and of handling on the mice in the pharmacological inhibition experiment, which may have led to delayed regain even in saline-treated SG-operated mice. Furthermore, cSst was provided in adulthood, after obesity onset, and has a partial effect on some but not all Sst-responsive tissues, while the genetic model is a full body, life-long knockout leading to a difference in body composition and possibly embryonic and post-embryonic development. Despite these differences, the main outcomes of inhibiting Sst signaling: smaller weight regain, improved glycemia and an elevation in GLP-1 levels after SG persist in the two models.

3.4. Somatostatin and maintenance of weight loss and low glycemia after SG

The effects of sst-ko and cSst treatment become significant about two months after surgery. One explanation is that the long-term effect relates to a Sst-mediated adaptive process that occurs normally after SG, such as changes in GH signaling [22,40,41]. It is also possible, that the short-term effects of surgery are not dependent on Sst-regulated processes, but are more affected by mechanical and entero-neuronal effects of surgery, while the long-term effects are more sensitive to metabolic, hormonal, and neuronal signaling that are regulated by Sst [42].

3.5. Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, Sst signaling is the only pathway whose inhibition and genetic knockout improves the already substantial outcomes of bariatric surgery in rodent models [21,43]. The Sst knockout model and the pan-Sst receptor inhibitor we used do not allow us to determine which hormone or what endocrine, exocrine, or neural system is most important for enhancing the metabolic outcomes of SG. We hypothesize that the outcomes of SG in sst-ko or cSst-treated mice may be attributed in part to GLP-1, since it was elevated in both models, and GLP-1 has prominent effects on the metabolic outcomes of bariatric surgery. However SG has the same metabolic effects in wild-type and glp1r-ko mice, pointing to the role of other factors in mediating the outcomes of surgery [44]. Improvement in the long-term metabolic outcomes of SG by Sst inhibition or deletion is likely not only a result of an increase in GLP-1 signaling.

While our mathematical model assumes that intestinal Sst secretion was increased following bariatric surgery, we did not measure this parameter. Sst is secreted by many tissues, and its plasma levels might not reflect its signaling in situ. The qualitative results of the model require that Sst will inhibit GLP-1 secretion and that either GLP-1 or a GLP-1 secretagogue will increase Sst secretion.

We studied here one bariatric surgery type, used only male mice under a specific dietary model for obesity, and did not include a post-surgical dietary, behavioral or pharmacological intervention that can sustain weight loss. Further research is required to extend to implications of this study to a preclinical setting, to determine the effects of Sst inhibition in broader contexts.

3.6. Conclusion

Bariatric surgery is an aggressive yet effective treatment for obesity and metabolic diseases. The long-term outcomes of surgery vary: while many patients display significant long-lasting weight loss, some patients experience partial or even full weight regain years after surgery [19]. Patients who regain weight or remain obese after bariatric surgery can be treated by lifestyle modifications, behavioral therapy, GLP-1 receptor agonists and other anti-obesity treatments [28]. Here, we provided evidence that genetic loss of Sst or pharmacological inhibition of Sst signaling reduces weight regain and sustains lower glycemia compared with untreated mice, months after surgery.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Mice

Animal experiments were approved by the Hebrew University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility on a strict 12-h light–dark cycle.

For the metabolic phenotyping of sst-ko mice (B6N.129S4(129S6)-Ssttm1Ute/J, Jackson Labs #:008117, background strain C57Bl/6 [45]), six-week-old male mice were fed on a high-fat high-sucrose (HFHS) diet (Envigo Teklad diets TD08811) for 110 days. sst-ko and heterozygous sibling controls were co-caged throughout the experiment.

For SG in sst-ko mice, six-week-old sst-ko male mice were fed an HFHS diet for 12 weeks. Mice were randomized to the surgical groups matching for weight. The mice were operated on and maintained over 3 months after surgery on an HFHS diet. sst-ko and heterozygous sibling controls were co-caged throughout the experiment.

For the pharmacologic intervention, six-week-old C57Bl/6 male mice were fed an HFHS diet for 11 weeks, operated on and maintained over 2 months after surgery on an HFHS diet. Mice were randomized to the treatment groups 1 week after surgery, matching for weight. cSst and saline-treated groups were co-caged.

4.2. Surgery

Mice underwent SG surgery as described previously [17]. Briefly, a midline incision through the skin and underlying linea alba was performed, followed by exposure and mobilization of the stomach. A 12 mm clip was placed horizontally across the stomach's greater curvature using a Ligaclip Multiple Clip Applier. The excluded part of the stomach was excised, the abdominal wall was sutured using 6–0 coated vicryl sutures (Ethicon, J551G), and the skin was closed with clips (Autoclip system, FST-12020-00). Sham surgeries included the abdominal incision, exposure and mobilization of the stomach, and closure of the body wall and skin. Each surgery lasted approximately 15–20 min. Mice were fasted overnight the day before surgery and during the day of surgery, and then returned to the HFHS diet. Post-surgical death was observed in approximately 15% of the SG-operated mice and 0% of the sham-operated mice within a week after SG surgery, and was attributed to leaks in the gastric sleeve, or an edema obstructing the gastric tract, with no effect of genotype on mortality. Mice in which a major abscess or splenomegaly was observed post-mortem were excluded from the analysis.

4.3. Cyclosomatostatin treatment

Cyclosomatostatin (cSst) was purchased from Tocris (Cat. No. 3493) and dissolved to a final concentration of 0.08% EtOH and saline. cSst was injected subcutaneously at 30 μg/kg body weight every evening from 7 days after the surgery until the end of the experiment.

4.4. Blood glucose, oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) and CGM

Blood glucose was measured with a glucometer Accu-Check (Roche Inc.) by tail bleeding. Non-fasting blood glucose refers to blood glucose level at 7–8 am when animals had ad libitum access to food and water throughout the night. OGTT was performed on mice fasted for 6 h between 7 am and 1 pm by oral gavage of 20% glucose solution in water 2 g/kg body weight. A mixed meal tolerance test was performed similarly, providing Ensure® Original 10 mL/kg by oral gavage after a 6-h fast between 7 am and 1 pm, Blood glucose was measured at 15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min after gavage.

Here and in all measurements and tissue/blood collection, the experimentalists were blinded to the experimental group and the mice of different experimental groups were co-housed to reduce possible biases and confounding factors.

Continuous glucose measurements (CGM) were performed using the FreeStyle Libre system by Abbot according to a recently published protocol [29]. Briefly, the CGM sensor was inserted through a small incision under the skin of the back of the mouse. The CGM was attached to the skin using sutures, and glucose was measured continuously for an average of 9–10 days. The sensor stores data for up to 8 h, and we had access to measurements between midnight and 6 pm.

4.5. Terminal blood collection

Mice were anesthetized using ketamine 100 mg/kg and xylazine 8 mg/kg diluted in 0.9% sodium chloride. Blood was extracted via terminal bleeding using heparin-coated syringes and 25G needles and transferred to lithium heparin-coated tubes (Greiner, MiniCollect, #450535). Aprotinin (Sigma–Aldrich, A6279), DPP4 inhibitor (Merck #MDPP4), and EDTA (final concentration 0.83 mM) were added to the blood sample to avoid degradation of glucagon and GLP-1. Blood was then centrifuged at 6,000 RCF for 1.5 min. Plasma was then collected and stored in liquid nitrogen until transferred to final storage at −80 °C.

4.6. Hormone measurement

Basal plasma hormones were measured following a 6-h fast between 7 am and 1 pm. Postprandial plasma hormones were measured following a 6-h fast between 7 am and 1 pm, and 15 min after an oral glucose or mixed meal challenge as described above. Hormones were measured using Ultra-Sensitive Mouse Insulin ELISA (Crystal Chem, #90080), Mouse Glucagon ELISA (Crystal Chem, #81518), Mouse C-peptide ELISA Kit (Crystal Chem, #90050) and V-Plex Total GLP-1 kit (Mesoscale, K1503PD-2). Samples in which hemolysis was detected were excluded from the analysis.

4.7. Plasma lipid analysis

Plasma samples were analyzed for triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDL, HDL using a Cobas c111 (Roche Diagnostics) automated clinical chemistry analyzer that was calibrated according to manufacturer guidelines.

4.8. Mathematical model

The following equations were used to model the interaction between GLP-1 (H) and Sst (S). Simulations were performed in Python. See SI text for details and values used in the simulations.

| (1) |

| (2) |

4.9. Statistics

Student's and Welch's t-test was performed to test statistical significance when two groups were compared. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was performed when a time series measurement was taken. Calculations were performed in GraphPad prism9 or R-studio.

See SI text for extended Materials and methods.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Doron Kleiman: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Yhara Arad: Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Shira Azulai: Investigation. Aaron Baker: Investigation. Michael Bergel: Investigation. Amit Elad: Investigation. Arnon Haran: Investigation. Liron Hefetz: Investigation. Hadar Israeli: Investigation. Mika Littor: Software. Anna Permyakova: Methodology, Investigation. Itia Samuel: Investigation. Joseph Tam: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition. Rachel Ben-Haroush Schyr: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Danny Ben-Zvi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

DK, YA, RBHS & DBZ conceived the study and designed the experiments; DK, YA, SA, AB, MB, AE, LH, HI, AP, IS, RBHS & DBZ performed the experiments; DK, YA, ML, AP, JT, RBHS & DBZ analyzed the data; DK, RBHS & DBZ wrote the manuscript. DBZ is the guarantor of the data. This study was funded by an ERC StG (803526), an Israel Science Foundation (ISF) research grant (967/18) awarded to DBZ, and an ISF research grant (158/18) awarded to J.T. D.BZ is a Zuckerman STEM faculty fellow.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2024.101979.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Tostivint H., Lihrmann I., Vaudry H. New insight into the molecular evolution of the somatostatin family. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;286(1–2):5–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorner M.O., Vance M.L., Hartman M.L., Holl R.W., Evans W.S., Veldhuis J.D., et al. Physiological role of somatostatin on growth hormone regulation in humans. Metabolism. 1990;39(9 Suppl. 2):40–42. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(90)90207-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strowski M.Z., Parmar R.M., Blake A.D., Schaeffer J.M. Somatostatin inhibits insulin and glucagon secretion via two receptor subtypes: an in vitro study of pancreatic islets from somatostatin receptor 2 knockout mice 1. Endocrinology. 2000;141(1):111–117. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.1.7263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rorsman P., Huising M.O. The somatostatin-secreting pancreatic δ-cell in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018:404–414. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0020-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Low M.J. The somatostatin neuroendocrine system: physiology and clinical relevance in gastrointestinal and pancreatic disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2004:607–622. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar U., Singh S. Role of somatostatin in the regulation of central and peripheral factors of satiety and obesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(7) doi: 10.3390/ijms21072568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomes-Porras M., Cárdenas-Salas J., Álvarez-Escolá C. Somatostatin analogs in clinical practice: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;1682 doi: 10.3390/ijms21051682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedraza-Arévalo S., Córdoba-Chacón J., Pozo-Salas A.I., López F.L., De Lecea L., Gahete M.D., et al. Not so giants: mice lacking both somatostatin and cortistatin have high GH levels but show no changes in growth rate or IGF-1 levels. Endocrinology. 2015;156(6):1958–1964. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Córdoba-Chacón J., Gahete M.D., Castaño J.P., Kineman R.D., Luque R.M. Somatostatin and its receptors contribute in a tissue-specific manner to the sex-dependent metabolic (fed/fasting) control of growth hormone axis in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300(1) doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00514.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zavros Y., Eaton K.A., Kang W., Rathinavelu S., Katukuri V., Kao J.Y., et al. Chronic gastritis in the hypochlorhydric gastrin-deficient mouse progresses to adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2005;24(14):2354–2366. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li N., Yang Z., Li Q., Yu Z., Chen X., Li J.C., et al. Ablation of somatostatin cells leads to impaired pancreatic islet function and neonatal death in rodents. 2018;9(6):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0741-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huising M.O., van der Meulen T., Huang J.L., Pourhosseinzadeh M.S., Noguchi G.M. The difference δ-cells make in glucose control. Physiology. 2018;33(6):403–411. doi: 10.1152/PHYSIOL.00029.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauge-Evans A.C., King A.J., Carmignac D., Richardson C.C., Robinson I.C.A.F., Low M.J., et al. Somatostatin secreted by islet δ-cells fulfills multipleRoles as a paracrine regulator of islet function. Diabetes. 2009;58(2):403–411. doi: 10.2337/db08-0792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luque R.M., Kineman R.D. Gender-dependent role of endogenous somatostatin in regulating growth hormone-axis function in mice. Endocrinology. 2007;148(12):5998–6006. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang J.L., Pourhosseinzadeh M.S., Lee S., Krämer N., Guillen J.V., Cinque N.H., et al. Paracrine signalling by pancreatic δ cells determines the glycaemic set point in mice. Nat Metab. 2024;6(1):61–77. doi: 10.1038/S42255-023-00944-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jepsen S.L., Wewer Albrechtsen N.J., Windeløv J.A., Galsgaard K.D., Hunt J.E., Farb T.B., et al. Antagonizing somatostatin receptor subtype 2 and 5 reduces blood glucose in a gut- and GLP-1R-dependent manner. JCI Insight. 2021;6(4) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.143228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abu-Gazala S., Horwitz E., Schyr R.B.-H., Bardugo A., Israeli H., Hija A., et al. Sleeve gastrectomy improves glycemia independent of weight loss by restoring hepatic insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2018;67(6) doi: 10.2337/db17-1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ben-Haroush Schyr R., Al-Kurd A., Moalem B., Permyakova A., Israeli H., Bardugo A., et al. Sleeve gastrectomy suppresses hepatic glucose production and increases hepatic insulin clearance independent of weight loss. Diabetes. 2021;70(10):2289–2298. doi: 10.2337/db21-0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlsson L.M.S., Sjöholm K., Jacobson P., Andersson-Assarsson J.C., Svensson P.-A., Taube M., et al. Life expectancy after bariatric surgery in the Swedish obese subjects study. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(16):1535–1543. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2002449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McTigue K.M., Wellman R., Nauman E., Anau J., Coley R.Y., Odor A., et al. Comparing the 5-year diabetes outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass: the national patient-centered clinical research network (PCORNet) bariatric study. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(5) doi: 10.1001/JAMASURG.2020.0087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evers S.S., Sandoval D.A., Seeley R.J. The physiology and molecular underpinnings of the effects of bariatric surgery on obesity and diabetes. Annu Rev Physiol. 2017:313–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulla C.M., Middelbeek R.J.W., Patti M.E. Mechanisms of weight loss and improved metabolism following bariatric surgery. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018:53–64. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albaugh V.L., He Y., Münzberg H., Morrison C.D., Yu S., Berthoud H.R. Regulation of body weight: lessons learned from bariatric surgery. Mol Metab. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sioka E., Tzovaras G., Perivoliotis K., Bakalis V., Zachari E., Magouliotis D., et al. Impact of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on gastrointestinal motility. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/4135813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmad A., Kornrich D.B., Krasner H., Eckardt S., Ahmad Z., Braslow A.M., et al. Prevalence of dumping syndrome after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and comparison with laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2019;29(5):1506–1513. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-03699-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Beek A.P., Emous M., Laville M., Tack J. Dumping syndrome after esophageal, gastric or bariatric surgery: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Obes Rev. 2017:68–85. doi: 10.1111/obr.12467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haris B., Saraswathi S., Hussain K. Somatostatin analogues for the treatment of hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2020;11 doi: 10.1177/2042018820965068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El Ansari W., Elhag W. Weight regain and insufficient weight loss after bariatric surgery: definitions, prevalence, mechanisms, predictors, prevention and management strategies, and knowledge gaps—a scoping review. Obes Surg. 2021:1755–1766. doi: 10.1007/s11695-020-05160-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleiman D., Littor M., Nawas M., Ben-Haroush Schyr R., Ben-Zvi D. Simple continuous glucose monitoring in freely moving mice. J Vis Exp. 2023;192 doi: 10.3791/64743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hansen L., Hartmann B., Bisgaard T., Mineo H., Jørgensen P.N., Holst J.J. Somatostatin restrains the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 and -2 from isolated perfused porcine ileum. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;278(6 41–6) doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.6.e1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jepsen S.L., Grunddal K.V., Albrechtsen N.J.W., Engelstoft M.S., Gabe M.B.N., Jensen E.P., et al. Paracrine crosstalk between intestinal L- and D-cells controls secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2019;317(6):E1081–E1093. doi: 10.1152/AJPENDO.00239.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elmentaite R., Kumasaka N., Roberts K., Fleming A., Dann E., King H.W., et al. Cells of the human intestinal tract mapped across space and time. Nature. 2021;597(7875):250–255. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03852-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldspink D.A., Lu V.B., Miedzybrodzka E.L., Smith C.A., Foreman R.E., Billing L.J., et al. Labeling and characterization of human GLP-1-secreting L-cells in primary ileal organoid culture. Cell Rep. 2020;31(13) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Briere D.A., Bueno A.B., Gunn E.J., Michael M.D., Sloop K.W. Mechanisms to elevate endogenous GLP-1 beyond injectable GLP-1 analogs and metabolic surgery. Diabetes. 2018;67:309–320. doi: 10.2337/db17-0607. American Diabetes Association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hefetz L., Ben-Haroush Schyr R., Bergel M., Arad Y., Kleiman D., Israeli H., et al. Maternal antagonism of Glp1 reverses the adverse outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy on mouse offspring. JCI Insight. 2022;7(7) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.156424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heppelmann B., Pawlak M. Peripheral application of cyclo-somatostatin, a somatostatin antagonist, increases the mechanosensitivity of rat knee joint afferents. Neurosci Lett. 1999;259(1):62–64. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00912-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Low M.J., Otero-Corchon V., Parlow A.F., Ramirez J.L., Kumar U., Patel Y.C., et al. Somatostatin is required for masculinization of growth hormone-regulated hepatic gene expression but not of somatic growth. J Clin Investig. 2001;107(12):1571–1580. doi: 10.1172/JCI11941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Der Meulen T., Donaldson C.J., Cáceres E., Hunter A.E., Cowing-Zitron C., Pound L.D., et al. Urocortin3 mediates somatostatin-dependent negative feedback control of insulin secretion. Nat Med. 2015;21(7):769–776. doi: 10.1038/nm.3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamir O., Afek A., Shani M., Cahn A., Raz I. Five years into the Israeli National Diabetes Program – are we on the right track? Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2021;37(6) doi: 10.1002/DMRR.3421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ben-Zvi D., Meoli L., Abidi W.M., Nestoridi E., Panciotti C., Castillo E., et al. Time-dependent molecular responses differ between gastric bypass and dieting but are conserved across species. Cell Metab. 2018;28(2):310–323.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dreyfuss J.M., Yuchi Y., Dong X., Efthymiou V., Pan H., Simonson D.C., et al. High-throughput mediation analysis of human proteome and metabolome identifies mediators of post-bariatric surgical diabetes control. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27289-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arble D.M., Sandoval D.A., Seeley R.J. Mechanisms underlying weight loss and metabolic improvements in rodent models of bariatric surgery. Diabetologia. 2015:211–220. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruinsma B.G., Uygun K., Yarmush M.L., Saeidi N. Surgical models of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery and sleeve gastrectomy in rats and mice. Nat Protoc. 2015;10(3):495–507. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson-Pérez H.E., Chambers A.P., Ryan K.K., Li B., Sandoval D.A., Stoffers D., et al. Vertical sleeve gastrectomy is effective in two genetic mouse models of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor deficiency. Diabetes. 2013;62(7):2380–2385. doi: 10.2337/db12-1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeyda T., Diehl N., Paylor R., Brennan M.B., Hochgeschwender U. Impairment in motor learning of somatostatin null mutant mice. Brain Res. 2001;906(1–2):107–114. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02563-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.