Visual Abstract

TO THE EDITOR:

Considerable advancements have occurred in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with hematological diseases, including knowledge of the omics of disease, to the development of small molecules, targeted agents, and cellular and gene therapies. Yet, improvements in survival have occurred mainly in well-developed world regions while remaining stable or modestly improved in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).1

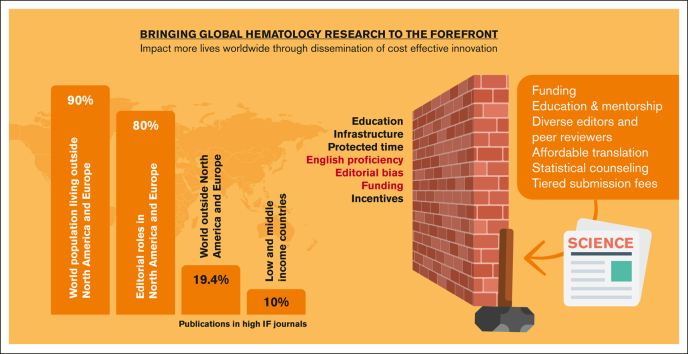

This disparity is driven by historical and geopolitical forces including health systems with restricted resources, lack of optimal diagnostic tools, and limited therapeutic armamentariums. Nonmalignant diseases like nutritional anemias, hemoglobinopathies, and infectious diseases have an uneven distribution across populations, being more prevalent in LMIC. Most humans alive today, >6.6 billion people, live in LMIC, and >90% of the world population lives outside North America and Europe.2

Paradoxically, most of the scientific advances published in the literature come from investigators working in institutions in wealthier regions. A bibliometric analysis in hematology, a reflection of research capacity, reveals that most indexed journals come from high-income countries (HIC),3,4 as are ∼70% of publications.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 This is not limited to hematology: from 1995 to 2015, 30 countries generated 93.9% of all publications indexed in PubMed. Of them, 21 are from the Americas and Europe, and 24 from HIC.5 Contributing factors to global inequity in research output and distribution are multiple, including the number of health professionals and their clinical workload; a lack in research education and English language proficiency; gaps in training, mentorship, and infrastructure; fewer funding opportunities; regulatory limitations; lack of incentives and recognition; and low government investment.15

Despite these limitations, meaningful research is performed worldwide. Historical examples of hematology research emerging from LMICs include the discovery of the different forms of hemophilia,16 the use of anabolic steroids in aplastic anemia,17 the cure for acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide,18,19 dose optimization of effective but expensive drugs, and the implementation of alternative models of care like outpatient hematopoietic cell transplantation.20 Other creative and cost-effective solutions to problems otherwise addressed with approaches too costly for LMIC may have been developed but gone unnoticed or unpublished. How can global hematology contributions be fostered? Systemic inequities in research capacity and output should be improved by increasing investment in research and education. Another key factor is to increase the presence of global hematology contributions in peer reviewed, high impact factor (IF) journals. Contributions published in high-IF journals are widely disseminated and read; they are frequently cited and influential, stimulating further research and shaping policies. Equally excellent global hematology research may, in some instances, affect more lives and decrease global disparities in patient outcomes than scientifically complex or expensive research. Successful examples of international research collaborations aimed at solving global issues across world regions exist (Table 1).

Table 1.

Representative international, longitudinal capacity building collaborations in hematology

| International outreach | Coaching institution | Aim |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Research Training Institute21 | ASH | Clinical research capacity building in Latin-America and Asia-Pacific |

| Consortium of Newborn Screening in Africa22 | ASH | Hemoglobinopathy screening and early intervention in sub-Saharan Africa |

| Gleevec International Patient Assistance Program23 | Max Foundation Novartis | Global access to imatinib for patients with CML worldwide |

| Global hematopoietic cell transplantation24 | University of Chicago | Developing transplant capacity in LMIC |

| Health Volunteers Overseas25 | ASH | Training and capacity building in LMIC |

| International Consortium on Acute Leukemia26 | ASH | Diagnosis and treatment of AML in Latin-America |

| International Outreach program27 | St Jude Children’s Hospital | Capacity building, and implementation of science and research in childhood cancer |

| Pediatric Oncology in Developing Countries28 | SIOP | Guideline development and implementation, research in childhood cancer |

| Sickle Cell Disease clinical trials in Africa29, 30 | Several | Clinical trial capacity building in Nigeria |

| Transfusion support in Africa31 | Several | Clinical trial and education in transfusion medicine in Africa |

| iCML Knowledge Center32 | iCMLf | Improve outcomes for patients with CML globally |

| CML LA experts Working Group33 | LALNET | CML treatment free remission recommendations in Latin-America |

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ASH, American Society of Hematology; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; iCMLf, International CML foundation; LALNET, Latin American Leukemia Net; SIOP, International Society of Pediatric Oncology.

Still, there is a wide geographical imbalance in publications in high-IF hematology journals. According to Journal Citation Reports, the median percentage of publications from countries outside North America and Europe in 2020 to 2022 was 19.4% (interquartile range, 16.6-21.5), and the number of publications in LMICs worldwide was 10.4% (interquartile range, 8.8-11.3; Table 2).

Table 2.

Contributions to high IF indexed in the hematology category of the Journal Citation Reports from 2020 to 2022 according to region of origin

| Journal | IF | Number of publications | HIC∗ |

LMIC∗ |

North America & Europe† |

Rest of the World† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries, n (%) | Publications, n (%) | Countries, n (%) | Publications, n (%) | Countries, n (%) | Publications, n (%) | Countries, n (%) | Publications, n (%) | |||

| Journal of Hematology Oncology | 28.5 | 938 | 37 (66.1) | 573 (61.1) | 19 (33.9) | 365 (38.9) | 27 (48.2) | 500 (53.3) | 29 (51.8) | 438 (46.7) |

| The Lancet Haematology | 24.7 | 1 78 | 44 (53.7) | 1 045 (88.7) | 38 (46.3) | 133 (11.3) | 29 (35.4) | 925 (78.5) | 53 (64.6) | 253 (21.5) |

| Blood | 20.3 | 23 377 | 55 (45.8) | 20 881 (89.3) | 65 (54.2) | 2496 (10.7) | 38 (31.7) | 18 816 (80.5) | 82 (68.3) | 4561 (19.5) |

| Circulation Research | 20.1 | 1 928 | 39 (65) | 1 733 (89.9) | 21 (35) | 195 (10.1) | 28 (46.7) | 1 608 (83.4) | 32 (52.3) | 320 (16.6) |

| Blood Cancer Journal | 12.8 | 971 | 34 (73.9) | 885 (91.1) | 12 (26.1) | 86 (8.9) | 27 (58.7) | 808 (83.2) | 19 (41.3) | 163 (16.8) |

| American Journal of Hematology | 12.8 | 2 201 | 43 (52.4) | 1 955 (88.9) | 39 (47.6) | 246 (11.1) | 32 (39) | 1 786 (81.1) | 50 (61) | 415 (18.9) |

| Leukemia | 11.4 | 3 000 | 44 (57.1) | 2 729 (90.9) | 33 (42.9) | 271 (9.1) | 32 (41.6) | 2 455 (81.8) | 45 (58.4) | 548 (18.2) |

| Experimental Hematology & Oncology | 11.4 | 252 | 22 (73.3) | 100 (39.7) | 8 (26.7) | 152 (60.3) | 18 (60) | 85 (33.7) | 12 (40) | 167 (66.3) |

| Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis | 10.4 | 2 359 | 42 (60.9) | 2 166 (91.8) | 27 (39.1) | 193 (8.2) | 30 (43.5) | 1 978 (83.8) | 39 (56.5) | 381 (16.2) |

| Haematologica | 10.1 | 5 331 | 48 (60) | 5 063 (94.9) | 32 (40) | 268 (5.1) | 34 (42.5) | 4 774 (89.5) | 46 (57.5) | 557 (10.5) |

| HemaSphere | 9.1 | 1 028 | 48 (57.8) | 959 (93.28) | 35 (42.2) | 69 (6.72) | 35 (42.2) | 922 (89.68) | 48 (57.8) | 106 (10.32) |

| Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology | 8.7 | 1 233 | 40 (72.7) | 1 100 (89.21) | 15 (27.3) | 133 (10.79) | 29 (52.7) | 987 (80.04) | 26 (47.3) | 246 (19.96) |

| Blood Advances | 7.6 | 3 814 | 45 (54.2) | 3 478 (91.19) | 38 (45.8) | 336 (8.81) | 31 (37.3) | 3 099 (81.25) | 52 (62.7) | 715 (18.75) |

| Thrombosis Research | 7.5 | 1 936 | 44 (61.1) | 1 667 (86.10) | 28 (38.9) | 269 (13.9) | 33 (45.8) | 1 524 (78.71) | 39 (54.2) | 412 (21.29) |

| Blood Reviews | 7.4 | 314 | 29 (69) | 289 (92.03) | 13 (31) | 25 (7.97) | 23 (54.8) | 262 (83.43) | 19 (45.2) | 52 (16.57) |

| Thrombosis and Haemostasis | 6.7 | 1 398 | 41 (60.3) | 1 253 (89.62) | 27 (39.7) | 145 (10.38) | 30 (44.1) | 1 127 (80.61) | 38 (55.9) | 271 (19.39) |

| British Journal of Haematology | 6.5 | 5 403 | 55 (48.7) | 4 804 (88.91) | 58 (51.3) | 599 (11.09) | 38 (33.6) | 4 311 (79.78) | 75 (66.4) | 1092 (20.22) |

| Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism | 6.3 | 2 230 | 39 (69.6) | 2 021 (90.62) | 17 (30.4) | 209 (9.38) | 30 (53.6) | 1 678 (75.24) | 25 (44.6) | 552 (24.76) |

| Critical Reviews in Oncology Hematology | 6.2 | 1 193 | 47 (59.5) | 895 (75.02) | 32 (40.5) | 298 (24.98) | 36 (45.6) | 815 (68.31) | 43 (54.4) | 378 (31.69) |

| Overall medians (IQR) | 10.1 (7.4-10.8) | 1 398 (971-2 359) | 43 (22-55) | 1 667 (100-20 881) | 28 (8-65) | 209 (25-2496) | 30 (18-38) | 1 525 (85-18 816) | 39 (12-82) | 381 (52-4561) |

IQR, interquartile range.

Data reflects the number of countries and publications from HIC and LMICs according to the World Bank that contributed publications to hematology journals indexed in the Journal of Citation Reports in the past 3 years. Journals in the first IF quartile were included.

Number of countries and publications from HIC in North America and Europe compared with the rest of the world.

“International” high-IF journals should be congruent with their mission that carries a moral responsibility for the whole world. However, editorial bias may exist. Randomized controlled trials in hematology and oncology, the gold standard for evidence in medical research, are more frequently published in journals with lower IF when they are authored by authors from LMIC than trials from HIC.34,35

One possible contributor is the composition of editorial boards. Like most hematology journals, 77% of all hematology editorial roles in 2022 were filled by persons from North America and Europe. Only 7% of editors were affiliated to institutions in South America, Africa, or Southeast Asia.3 The issue is amplified when considering high-IF journals in general, in which ∼80% of editorial roles are filled by those from North America and Europe, with only 1% filled by individuals in LMIC.4,36 Notably, 71.1% of editorial roles are filled by non-Hispanic whites, and 20% of editors had repeated roles in >1 journal.4,36 This disparity places the spotlight on issues that are more relevant in parts of the world more widely represented in these boards. Editors direct the narrative and content of journals by selecting in an unblinded manner which submissions are to be published, thus have the potential for biased decision-making.37,38 It might be more difficult for such members to fully and equitably appreciate the value of contributions addressing issues of relevance to LMIC. Studies should be judged on scientific novelty but also on their potential for advancing diagnostic and therapeutic capacity through cost-effective means. The assignment of contributions to editors who are attuned to the issues presented is thus logical and necessary. Furthermore, the careful selection of blinded peer reviewers who are both experts in the field and familiar with the global problems being addressed, is key.

This does not mean setting a lower bar for investigators from LMIC, or that journals should alter their quality standards. Rather, given that scientific publishing is a highly lucrative enterprise, the playing field could be leveled by offering support to investigators who need it. Examples of support from international journals could include offering education and mentorship opportunities, the exemption of English proficiency as a determinant of acceptance, the offer of affordable language editing services and statistical counseling and support, and the creation of tiered submission and open-access fees based on a thorough assessment of payment capacity based not only on gross macroeconomic indices.

Other solutions to move research performed globally to the forefront include the creation of sibling journals under the umbrella of high-profile academic societies or publishing groups, to expand access without diverting high-impact research to lower IF journals. To advance science and global health, medical journals, editors, and peer-reviewers should work as true partners in science with investigators and physicians worldwide for the betterment of humanity.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.G.-D.L. received honoraria for talks from AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas, Janssen, Novartis, and Sanofi, and served on the advisory board of Pfizer and Janssen. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

Contribution: J.C. designed the project, wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript, and approved the final version; A.G.-D.L. wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript, and approved the final version; A.N.-P. and L.G.-F. collected data, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and approved the final version; and H.M., V.M., A.E.-B., H.T., and C.P. reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version.

References

- 1.Zhang N, Wu J, Wang Q, et al. Global burden of hematologic malignancies and evolution patterns over the past 30 years. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13(1):82. doi: 10.1038/s41408-023-00853-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The World Bank Wold Bank Open Data. https://data.worldbank.org/ Accessed 23 December 2023.

- 3.Noyola-Perez A, Gil-Flores L, Martinez-Espinosa HA, et al. Global representation among journal editors in haematology: are we diverse, equitable, and inclusive? Lancet Haematol. 2023;10(4):e246–e247. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(23)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel SR, Riano I, Abuali I, et al. Race/ethnicity and gender representation in hematology and oncology editorial boards: what is the state of diversity? Oncologist. 2023;28(7):609–617. doi: 10.1093/oncolo/oyad103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontelo P, Liu F. A review of recent publication trends from top publishing countries. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):147. doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0819-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L, Ye X, Sun Y, Deng AM, Qian BH. Hematology research output from Chinese authors and other countries: a 10-year survey of the literature. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13045-014-0103-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aldossary NJ, Rashid AM, Waris A, et al. Bibliometric analysis of the literature on von Willebrand disease: research status and trends. Acta Biomed. 2023;94(1) doi: 10.23750/abm.v94i1.14086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulduk T. Aplastic anemia from past to the present: a bibliometric analysis with research trends and global productivity during 1980 to 2022. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023;102(36) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000034862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen ML, Zhang HC, Yang EP. Current status and hotspots evolution in myeloproliferative neoplasm: a bibliometric analysis from 2001 to 2022. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;27(10):4510–4519. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202305_32457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duan Q, Li Y, Ou L, et al. Global research trends on the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a bibliometric and visualized study. J Cancer. 2022;13(6):1785–1795. doi: 10.7150/jca.68453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okoroiwu HU, Lopez-Munoz F, Povedano-Montero FJ. Bibliometric analysis of global sickle cell disease research from 1997 to 2017. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2022;44(2):186–196. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2020.09.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ou Y, Zhan Y, Zhuang X, et al. A bibliometric analysis of primary immune thrombocytopenia from 2011 to 2021. Br J Haematol. 2023;201(5):954–970. doi: 10.1111/bjh.18692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ou Z, Qiu L, Rong H, et al. Bibliometric analysis of chimeric antigen receptor-based immunotherapy in cancers from 2001 to 2021. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1–18. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.822004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seo B, Kim J, Kim S, Lee E. Bibliometric analysis of studies about acute myeloid leukemia conducted globally from 1999 to 2018. Blood Res. 2020;55(1):1–9. doi: 10.5045/br.2020.55.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaba M, Birhanu Z, Fernandez Villalobos NV, et al. Health research mentorship in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. JBI Evid Synth. 2023;21(10):1912–1970. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-22-00260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pavlovsky A. Contribution to the pathogenesis of hemophilia. Blood. 1947;2(2):185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanchez-Medal L, Gomez-Leal A, Duarte L, Guadalupe Rico M. Anabolic androgenic steroids in the treatment of acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 1969;34(3):283–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang ME, Ye YC, Chen SR, et al. Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 1988;72(2):567–572. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen ZX, Chen GQ, Ni JH, et al. Use of arsenic trioxide (As2O3) in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL): II. Clinical efficacy and pharmacokinetics in relapsed patients. Blood. 1997;89(9):3354–3360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruiz-Arguelles GJ, Gomez-Almaguer D, David-Gomez-Rangel J, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with non-myeloablative conditioning in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia eligible for conventional allografting: a prospective study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45(6):1191–1195. doi: 10.1080/10428190310001642846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sung L, Rego E, Riva E, et al. Development and evaluation of a hematology-oriented clinical research training program in Latin America. J Cancer Educ. 2017;32(4):845–849. doi: 10.1007/s13187-016-1015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green NS, Zapfel A, Nnodu OE, et al. The Consortium on Newborn Screening in Africa for sickle cell disease: study rationale and methodology. Blood Adv. 2022;6(24):6187–6197. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022007698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Umeh CA, Garcia-Gonzalez P, Tremblay D, Laing R. The survival of patients enrolled in a global direct-to-patient cancer medicine donation program: the Glivec International Patient Assistance Program (GIPAP) EClinicalMedicine. 2020;19 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poudyal BS, Tuladhar S, Neupane S, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in nepal: international partnership, implementation steps, and clinical outcomes. Transplant Cell Ther. 2022;28(5):268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2022.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Society of Hematology Health Volunteers Overseas. https://www.hematology.org/global-initiatives/health-volunteers-overseas Accessed 23 December 2023.

- 26.Rego EM. Impact of the ICAL on the treatment of acute leukemia. Blood Adv. 2017;1(8):516. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017002147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ribeiro RC. Improving survival of children with cancer worldwide: the St. Jude International Outreach Program approach. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2012;172:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howard SC, Davidson A, Luna-Fineman S, et al. A framework to develop adapted treatment regimens to manage pediatric cancer in low- and middle-income countries: the Pediatric Oncology in Developing Countries (PODC) Committee of the International Pediatric Oncology Society (SIOP) Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(S5) doi: 10.1002/pbc.26879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hegemann L, Narasimhan V, Marfo K, Kuma-Aboagye P, Ofori-Acquah S, Odame I. Bridging the access gap for comprehensive sickle cell disease management across sub-Saharan Africa: learnings for other global health interventions? Ann Glob Health. 2023;89(1):76. doi: 10.5334/aogh.4132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galadanci NA, Abdullahi SU, Tabari MA, et al. Primary stroke prevention in Nigerian children with sickle cell disease (SPIN): challenges of conducting a feasibility trial. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(3):395–401. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maitland K, Olupot-Olupot P, Kiguli S, et al. TRACT Group Transfusion volume for children with severe anemia in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(5):420–431. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.International Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Foundation iCMLf Knowledge Center. https://knowledge.cml-foundation.org/

- 33.Pavlovsky C, Abello-Polo V, Pagnano K, et al. Treatment-free remission in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: recommendations of the LALNET expert panel. Blood Adv. 2021;5(23):4855–4863. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wells JC, Sharma S, Del Paggio JC, et al. An analysis of contemporary oncology randomized clinical trials from low/middle-income vs high-income countries. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(3):379–385. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noyola-Perez AO-CA, Patel MI, Cortes J, et al. Disparities in phase 3 leukemia trials from the last decade: a long way to go. Blood. 2023;142(suppl 1):494 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawalha L, Kelkar AH, Mohyuddin GR, Goodman AM, Gagelmann N, Al Hadidi S. Analysis of repeated roles in editorial boards at oncology focused journals. J Cancer Policy. 2023;35:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpo.2022.100380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris M, Marti J, Watt H, Bhatti Y, Macinko J, Darzi AW. Explicit bias toward high-income-country research: a randomized, blinded, crossover experiment of English clinicians. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(11):1997–2004. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yousefi-Nooraie R, Shakiba B, Mortaz-Hejri S. Country development and manuscript selection bias: a review of published studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]