Abstract

Infectious diseases caused by arboviruses are a public health concern in Pakistan. However, studies on data prevalence and threats posed by arboviruses are limited. This study investigated the seroprevalence of arboviruses in a healthy population in Pakistan, including severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV), Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV), Tamdy virus (TAMV), and Karshi virus (KSIV) based on a newly established luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) assays, and Zika virus (ZIKV) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). Neutralizing activities against these arboviruses were further examined from the antibody positive samples. The results showed that the seroprevalence of SFTSV, CCHFV, TAMV, KSIV, and ZIKV was 17.37%, 7.58%, 4.41%, 1.10%, and 6.48%, respectively, and neutralizing to SFTSV (1.79%), CCHFV (2.62%), and ZIKV (0.69%) were identified, as well as to the SFTSV-related Guertu virus (GTV, 0.83%). Risk factors associated with the incidence of exposure and levels of antibody response were analyzed. Moreover, co-exposure to different arboviruses was demonstrated, as thirty-seven individuals were having antibodies against multiple viruses and thirteen showed neutralizing activity. Males, individuals aged ≤40 years, and outdoor workers had a high risk of exposure to arboviruses. All these results reveal the substantial risks of infection with arboviruses in Pakistan, and indicate the threat from co-exposure to multiple arboviruses. The findings raise the need for further epidemiologic investigation in expanded regions and populations and the necessity to improve health surveillance in Pakistan.

Keywords: Arbovirus, Pakistan, Seroprevalence, Tick-borne virus, Mosquito-borne virus

Highlights

-

•

The LIPS assay was established to detect antibodies against arboviruses in humans.

-

•

Serologic evidence suggested human exposure to multiple arboviruses in Pakistan.

-

•

Co-exposure events suggested high risks of infection with arboviruses in Pakistan.

-

•

Village Chak is an important epidemiologic area of arboviruses.

1. Introduction

Pakistan is an agricultural country in South Asia, bordering China, India, Afghanistan, and Iran. Approximately two-thirds of the country's population lives in rural areas and depends on agriculture and animal husbandry, often coming into direct contact with livestock outdoors, putting them at risk for zoonotic infections. Numerous mosquito-borne viral infections were reported or confirmed in multiple region of Pakistan, which caused serious public health problems (Butt et al., 2021; Khan et al., 2022). In 2016–2017, an outbreak of chikungunya fever resulted occurred, probably attributed to the widespread of Aedes mosquitoes which are the vectors of Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) (Badar et al., 2020). The first dengue fever virus (DENV) infected case was identified in Pakistan in 1994. The prevalence of DENV has been found widely distributed five provinces of Pakistan, including Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, Kashmir, Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), and Sindh (Awan et al., 2021). The disease of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF), caused by the tick-borne Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV), is a major public health concern in Pakistan. Since the first report of CCHF in 1976, there have been several CCHFV infections in different regions of this country, which showed an increased prevalence after 2010 (Waris et al., 2022). Currently, Pakistan is still at high risk of CCHF endemic due to the lack of primary healthcare facilities and public awareness about the spread and control of ticks (Atif et al., 2017). It is important to improve surveillance of arboviruses to promote preparation for outbreaks associated with these viruses.

Risks of infection with emerging arboviruses in Pakistan need increasing attention. Although no human cases have been reported, arboviruses, which are associated with human disease, such as Hazara virus, Dera Ghazi Khan virus, and Wad Medani virus, have been isolated decades ago from tick species like Ixodes redikorzevi, Alticola roylei, Hyalomma dromedarii, and Hyalomma anatolicum anatolicum, which are the predominant species in Pakistan (Begum et al., 1970a, 1970b). Unlike the widespread of DENV prevalent in five provinces of Pakistan (Awan et al., 2021), only one human infection with Zika virus (ZIKV) was identified based on serologic evidence in 1983 (Darwish et al., 1983a), despite of the emerging or re-emerging epidemics of ZIKV in other South Asian countries (Yadav et al., 2019). It was speculated that ZIKV infection might be misdiagnosed as dengue fever, probably because that examination of ZIKV infection was not including in the surveillance system or hospitals in Pakistan (Butt et al., 2016). To date, past human infections with arboviruses like CCHFV (Zohaib et al., 2020a) and severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) (Zohaib et al., 2020b) in Pakistan have been identified in healthy populations based on serologic surveys, and the presence of novel viruses with serologic correlation to these viruses was indicated. So, there could be increasing threats and challenges posed by emerging arboviruses, which needs to be surveyed and monitored. Recently, novel arboviruses with the potential to infect humans have been identified in Xinjiang, China, which borders Pakistan (Moming et al., 2021; Bai et al., 2022). However, it is unknown whether these arboviruses are present in Pakistan.

Serologic surveys are commonly performed to reveal past infection of viruses among animals and humans, which could indicate the risks of arbovirus spillover from vectors to hosts. Based on serologic surveys, this study was designed to investigate the seroprevalence of tick-borne viruses having been identified from ticks in regions and/or countries surrounding Pakistan, including CCHFV (Zohaib et al., 2020a), Tamdy virus (TAMV) (Moming et al., 2021), SFTSV, Guertu virus (GTV) (Shen et al., 2018), and Karshi virus (KSIV) (Bai et al., 2022), and the mosquito-borne ZIKV, which was widespread in most other countries but appears to have limited impact in Pakistan (Butt et al., 2016; Zohaib et al., 2020b). The viral exposure associated factors and the incidence of co-exposure to multiple viruses in human populations of Pakistan were further investigated and characterized. The results revealed the substantial seroprevalence of arboviruses and risks of co-exposure to these viruses in Pakistan, which emphasized the need for proactive and effective epidemiologic surveillance.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cells and viruses

African green monkey kidney cells (CCL-81), African green monkey kidney E6 cells (ATCC-1586), baby hamster kidney cells (CCL-10), and human embryonic kidney cells (CRL-11268) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle medium (NZK biotech, China) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, USA) and Eagle's Minimum Essential Medium (NZK Biotech, China) with 10% FBS.

SFTSV strain WCH (IVCAS 6.6088), CCHFV strain YL16070 (IVCAS 6.6329), TAMV strain YL16082 (IVCAS 6.7499), KSIV strain WJQ16209 (IVCAS 6.7465), ZIKV strain SZ-WIV01 (IVCAS 6.6110), and GTV strain DXM (IVCAS 6.6106) were obtained from NVRC.

2.2. Antibodies and other reagents

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the nucleoprotein (NP) of SFTSV (Zhang et al., 2017), CCHFV (Guo et al., 2017), and TAMV (Moming et al., 2021), and the envelope protein (E) of KSIV (Bai et al., 2022) and ZIKV (Dai et al., 2018b) were prepared as described previously, and were used as primary antibodies for immunofluorescence assays (IFAs), respectively, to confirm expression of viral NP. Goat anti-human IgG + IgM + IgA H&L conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Abcam, China) and goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Abcam, China) were used as secondary antibodies for immunofluorescence assays (IFAs). Goat anti-human IgG H&L conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Abcam, Shanghai, China), TMB Chromogen Solution (Beyotime, China), and stop Solution (Beyotime, China) were used in ELISA as secondary antibody, substrate of color reaction, and stop reagent, respectively.

2.3. Collection of human serum samples

Serum samples from healthy individuals were collected in 2019 from basic health care units, diagnostic laboratories, and hospitals in Faisalabad of Punjab Province, Pakistan, including blood donors, pregnant females, and individuals seeking care for minor health issues such as hypertension and diabetes monitoring (Supplementary Table S1). All participants provided informed consent, either written or verbal, depending on their level of literacy. Trained health personnel provided all participants with appropriate information about the research process to all participants. Sociodemographic data, including age, gender, occupations, and history of animal contact, were collected by interview (To collect sociodemographic data, the individuals from Faisalabad were interviewed by the clinicians who are responsible for sample collection on the first day of the visit, and the personal information was recorded on a sheet with sample ID, age, gender, occupation, location, and animal contact. These data were used to investigate the risk of arbovirus exposure using statistical analyses based on antibody responses.). Fifty-five serum samples from healthy individuals archived in NVRC were used as controls. Ethical approval was obtained, and the study was assigned an approval number. None of the samples tested had previously been included in another study.

2.4. Serologic tests

Luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) assays for the detection of antibodies against SFTSV, TAMV, and KSIV were performed as previously described (Bai et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2022; Moming et al., 2023). Construction of LIPS assays based on CCHFV was performed as previously described (Burbelo et al., 2019). An in-house ELISA capable for the detection of IgG antibodies against ZIKV was developed previously (Dai et al., 2018a). IFAs were performed as described in details (Zohaib et al., 2020a).

Microneutralization assays of SFTSV, GTV, CCHFV, TAMV, KSIV, and ZIKV were performed as described previously (Dai et al., 2018a; Zohaib et al., 2020a, 2020b; Moming et al., 2021; Bai et al., 2022). IFAs were performed to visualize viral infection in each well. Neutralization titres were expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution that prevented virus infection in three replicates.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 19 (IBM Corporation, USA) and GraphPad Prism 8 (San Diego, USA). Correlations between host risk factors and viral infection were analyzed using chi-squared tests. Prevalence along with 95% confidence interval (CIs) were calculated. Positive samples were also analyzed statistically for association of age, gender, job and animal contact by using the χ2 test (or Fisher's exact test) at 95% confidence interval. A P-value <0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Seroprevalence of SFTSV, CCHFV, TAMV, KSIV, and ZIKV among people in Pakistan

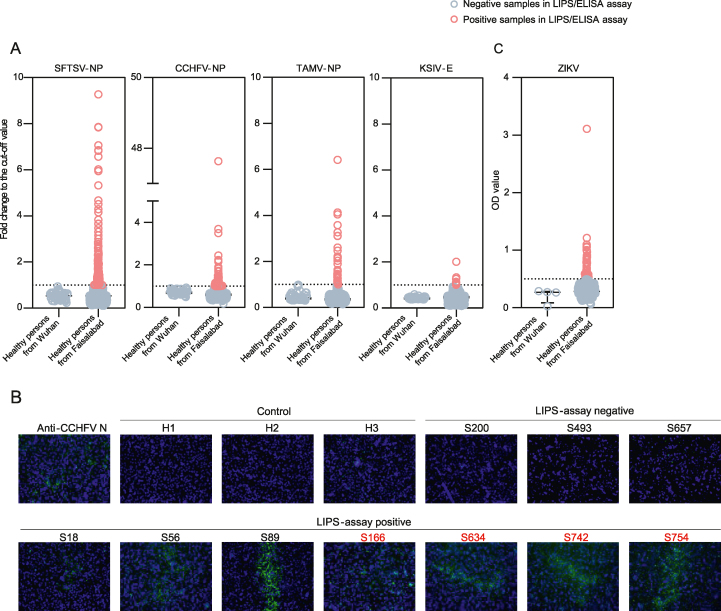

During 2019, a total of 725 human serum samples were collected from healthy individuals in Faisalabad, Pakistan. Of these samples, 539 (74.3%) were from males and 186 (25.7%) were from females. The median age was 37 years, and most of the subjects (549, 75.7%) had outdoor occupations. More than half of them (485, 66.9%) had direct contact with animals (Supplementary Table S1). Among the 725 serum samples, the highest seroprevalence was observed for SFTSV (126, 17.38%), followed by CCHFV (55, 7.59%), TAMV (32, 4.41%) and KSIV (8, 1.10%) according to the results of the LIPS assays (Table 1, Fig. 1A). While the LIPS assays for SFTSV, TAMV and KSIV have been previously validated by IFAs, resulting in the confirmation rates of 82.9%, 89.7%, and 100%, respectively (Bai et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2022; Moming et al., 2023), the assays for CCHFV antibodies were also confirmed in this study. Of the 40 randomly selected CCHFV LIPS-positive samples, 35 were positive by IFA, and all ten LPS-negative samples were still negative for CCHFV antibodies, indicating a confirmation rate of 87.50% (Fig. 1B). In addition, of all serum samples tested, 47 (6.48%) samples were positive for ZIKV antibodies by ELISA (Table 1, Fig. 1C). In total, 219 (30.21%) of the sampled population had antibodies against the tested arboviruses. These results reveal the prevalence of arboviruses in the population of Pakistan and the risk of infection by these viruses.

Table 1.

Seroprevalence and neutralizing activities of SFTSV, GTV, CCHFV, TAMV, KSIV, and ZIKV in healthy individuals in Pakistan.

| Category | Antibody positive samplesa n, % (95% CI)a |

Neutralizing activity positive samples n, % (95% CI) |

Neutralization titer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tick-borne virus | SFTSV | 126, 17.38% (14.79–20.31) | 13, 1.79% (1.05–3.04) | 20–40 |

| CCHFV | 55, 7.59% (5.87–9.74) | 19, 2.62% (1.68–4.07) | 20–80 | |

| TAMV | 32, 4.41% (3.14–6.16) | 0 | N/A | |

| KSIV | 8, 1.10% (0.56–2.16) | 0 | N/A | |

| Mosquito-borne virus | ZIKV | 47, 6.48% (4.91–8.51) | 5, 0.69% (0.29–1.6) | 10–20 |

| Total | 219, 30.21% (26.86–33.56) | 37, 5.10% (3.50–6.71) | N/A | |

CI, confidence interval; N/A, not applicable.

Seroprevalence of SFTSV, CCHFV, TAMV, and KSIV were calculated based on the results of LIPS assays, and the seroprevalence of ZIKV was determined based on the ELISA results.

Fig. 1.

Seroprevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV), Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV), Tamdy virus (TAMV), Karshi virus (KSIV) and Zika virus (ZIKV) among humans in Pakistan. A The levels of antibody response to SFTSV, CCHFV, TAMV, and KSIV were determined by luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) assays and were expressed as the fold change of luciferase activity to cut-off values. B Representative immunofluorescence assay (IFA) results of human serum samples having antibody response to CCHFV. Images of three LIPS-negative samples and seven LIPS-positive samples are presented. The samples having neutralization to CCHFV are indicated by red characters. Three samples from Wuhan, China are shown as control, and the positive control was blotted using a polyclonal antibody specific to CCHFV NP. C The levels of antibody response to ZIKV were measured by ELISA and were shown as the OD values.

Serologic exposure to SFTSV, CCHFV, and ZIKV was further confirmed by MNT (Table 1). Although a high proportion of samples (126/725, 17.38%) showed antibody response to SFTSV, only thirteen (13/725, 1.79%) samples were found to have neutralizing antibodies to this virus with titers of 20–40. Of the 55 CCHFV LIPS-positive samples, nineteen (19/725, 2.62%) showed neutralizing activity with titers ranging from 20 to 80. Only four of the 47 ZIKV LIPS-positive samples showed neutralizing activity with titers of 10–20, indicating a low ZIKV infection rate (4/725, 0.55%). In total, 37 LIPS-positive samples (5.10%) showed neutralizing activities for arboviruses, including SFTSV, CCHFV, and ZIKV. However, all TAMV and KSIV LIPS-positive samples were negative for virus neutralizing activity (Table 1).

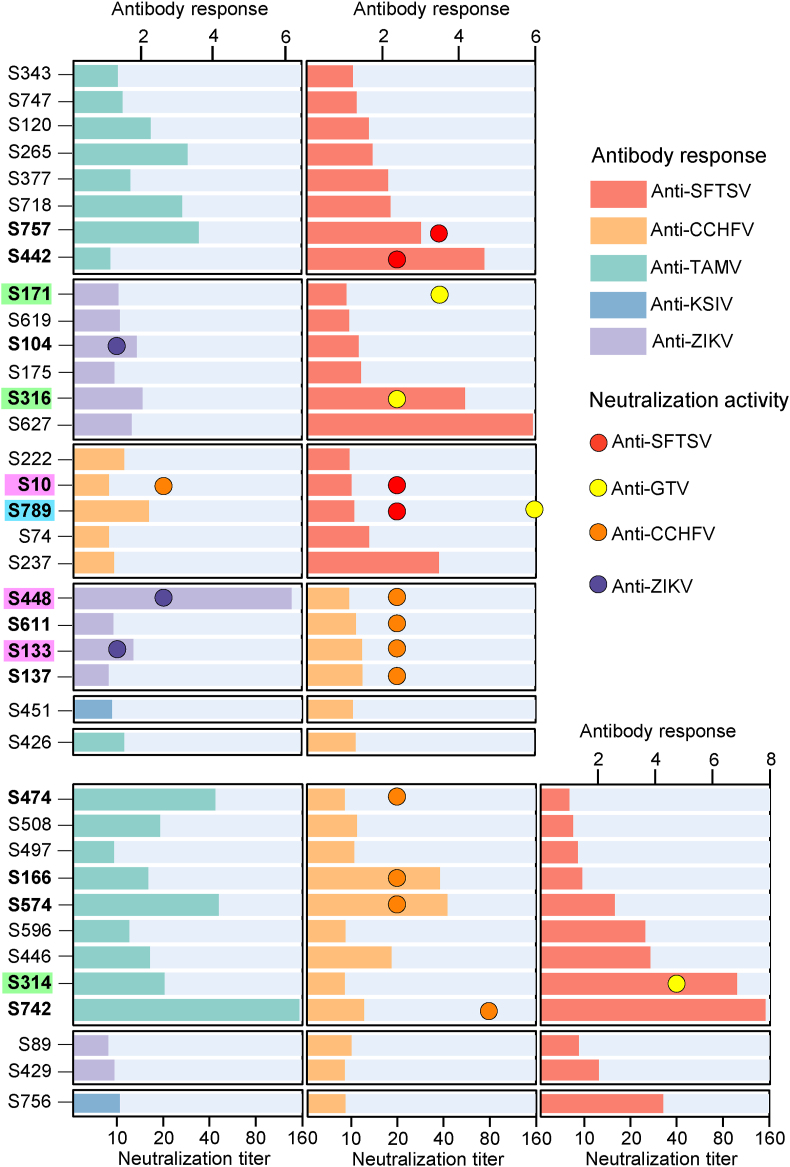

3.2. People in Pakistan had co-exposure to different arboviruses

People in Pakistan had co-exposure to two or more different viruses (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S2). While 182 (25.10%) antibody-positive samples had antibody response to one of the tested viruses, there are 37 individuals (5.10%) with antibody response to more than one virus, including 25 (3.45%) samples to two viruses (SFTSV-TAMV, SFTSV-ZIKV, SFTSV-CCHFV, CCHFV-ZIKV, CCHFV-KSIV, and CCHFV-TAMV, corresponding to 8, 6, 5, 4, 1, and 1 samples, respectively) and 12 (1.66%) samples to three viruses (SFTSV-CCHFV-TAMV, SFTSV-CCHFV-ZIKV, and SFTSV-CCHFV-KSIV, corresponding to 9, 2, and 1 samples, respectively). Ten (1.38%) of them were neutralized to one of the viruses to which they had antibody responses, and three others (0.41%) showed neutralization to two viruses to which they had antibody responses (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S2). These results suggested a high risk of infection with different arboviruses in humans in Pakistan.

Fig. 2.

Serologic evidence of human co-exposure to multiple arboviruses in Pakistan. Antibody titers to different viruses are shown in columns, and neutralizing activity against viruses is presented in colored circles. Cases with antibody titers to two or three viruses and neutralizing activity against one or two of these viruses are shown in bold. Cases with neutralizing activity against severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) and Guertu virus (GTV) are shown in light blue, and those with neutralizing activity against two other viruses are shown in lavender. Cases with antibody response to SFTSV and neutralizing activity against GTV are shown in light green. Antibody titers are expressed as the fold changes in luciferase activity or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) optical density values compared to cut-off values. Neutralizing titers are expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution that prevents viral infection.

3.3. The SFTSV-related virus, GTV, was prevalent and caused serologic exposure in humans in Pakistan

Neutralization to the SFTSV-related GTV was found in the SFTSV antibody-positive samples. Of the 126 SFTSV antibody-positive samples, six samples had neutralizing antibodies to GTV with the titers ranging from 20 to 160, suggesting an infection rate associated with this virus of 0.83% (Supplementary Table S2). The prevalence of GTV was further suggested by the analysis of neutralizing antibody titers to this virus. Infection with SFTSV or GTV could not be distinguished in samples S134 and S251 having neutralization to both viruses at comparable titers (20 or 40), probably due to serological cross-reaction between the them (Supplementary Table S2). S789 with antibody response to CCHFV and SFTSV had neutralization to GTV at a much higher titer of 160 than to SFTSV (titer = 20), suggesting that this individual was probably more exposed to GTV than to SFTSV. S171, S316, and S314 had antibody responses to SFTSV but showed neutralizing activity to GTV and not to SFTSV (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S2), confirming that GTV infection had occurred in these three individuals. Therefore, in addition to SFTSV, GTV is also prevalent in Pakistan and poses an infectious threat to the population.

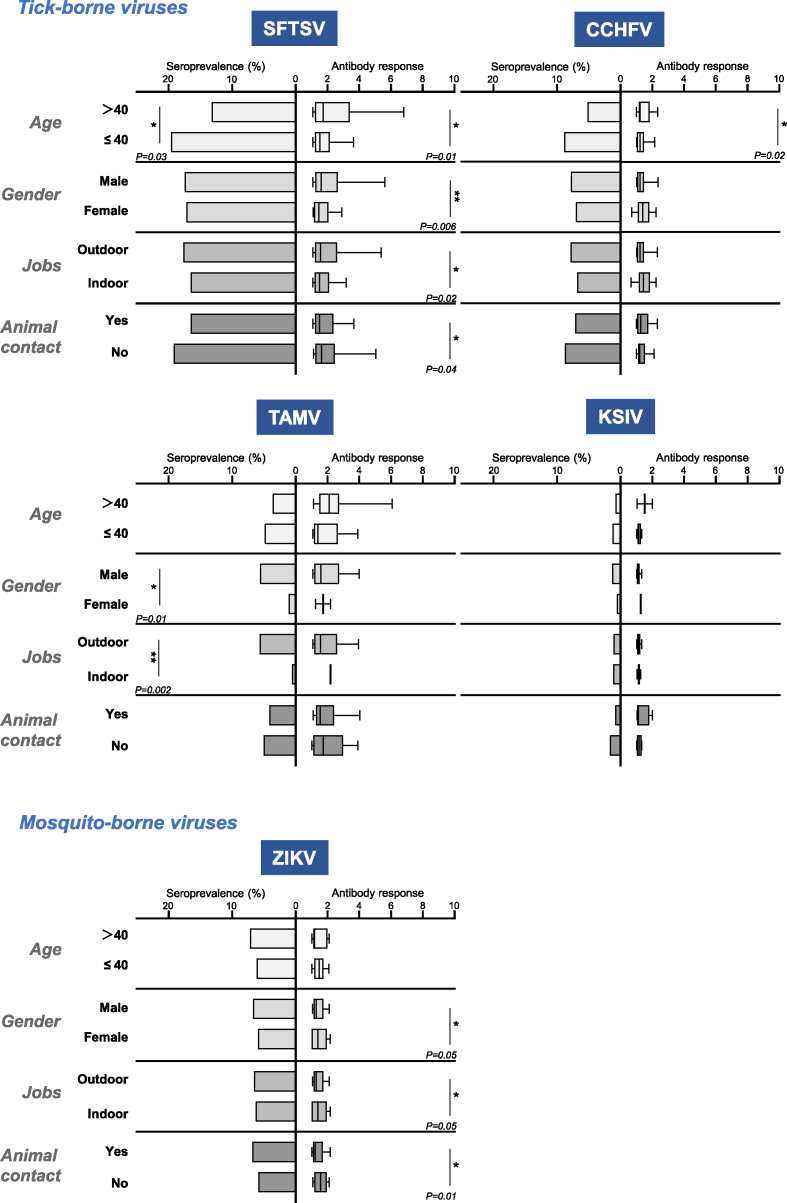

3.4. Risk factors may be associated with exposure to different arboviruses

Populations could be at different risk levels for infection with these arboviruses tested (Fig. 3, Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). People aged ≤40 years had higher seroprevalence rates of SFTSV, CCHFV, TAMV, and KSIV than those aged >40 years, but with no significant difference (P = 0.08, 0.44, and 0.57, respectively), which people aged ≤40 years had seroprevalence rates of SFTSV than those aged >40 years in the manner of significance (P = 0.03). In contrast, the seroprevalence rate of ZIKV was higher in persons aged >40 than in those aged ≤40, and no significant difference (P = 0.57) was found between the two groups of persons. Men and women had comparable seroprevalence rates of SFTSV, CCHFV, KSIV, and ZIKV, while the rate of TAMV was significantly higher in men than in women (P = 0.01). This was similar to the rates among people with indoor and outdoor jobs. Those with outdoor jobs were exposed to TAMV at a significantly higher rate than those with indoor jobs (P = 0.002). The rates of SFTSV, CCHFV, and ZIKV were slightly higher among people with outdoor jobs than among those with indoor jobs without any difference of significance (P = 0.851, 0.06 and 0.881, respectively), while this was opposite to the rate of KSIV in the two population groups (P = 0.962). People who did not have contact with animals had higher seroprevalence rates of SFTSV, CCHFV, TAMV, and KSIV than those who did, while people who had contact with animals had higher seroprevalence of ZIKV than those who did not. However, none of these differences was significant.

Fig. 3.

Risk factors for transmission of arboviruses based on seroprevalence and antibody levels. Seroprevalence of different viruses is shown in columns, and antibody responses are shown in box plots with 10–90% percentiles. The titer of the antibody response is indicated by the fold change of luciferase activity by luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) optical density values compared to cut-off values. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for statistical analysis. Individuals with no significant difference are not indicated in the figure. Asterisk indicates statistically significant differences (∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01).

Correlations between these groups of individuals and antibody responses were also characterized, as reflected by the levels of luciferase activity by using LIPS assays (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S3). Significantly higher antibody responses to SFTSV were found in individuals aged >40 years (P = 0.01), in males (P = 0.006), and in those who worked outdoors (P = 0.02) and had no contact with animals (P = 0.04) than in those aged ≤40 years, in females, and in those who worked indoors and had contact with animals, respectively. This suggests a stronger antibody response to SFTSV in these individuals. Individuals aged >40 years had a significantly higher antibody response to CCHFV than those aged ≤40 years (P = 0.02). Females and indoor workers had a higher, but not significant, antibody response to CCHFV than males and outdoor workers. Individuals with or without animal contact had no effect on the antibody response levels to CCHFV. Females (P = 0.05) and individuals with indoor jobs (P = 0.05) and no animal contact (P = 0.01) had significantly higher antibody responses to ZIKV, while those aged ≤40 had a higher, but not significant, response than those aged >40. Antibody response levels to TAMV and KSIV were not significantly different between the groups analyzed (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S3). However, among individuals with antibody responses to the viruses tested, we found no significant difference in the rates of neutralizing activity against SFTSV, GTV, or CCHFV in any of the groups analyzed (Supplementary Table S4).

More than half of the 37 individuals with neutralizing activity to arboviruses were male (29, 78.38%), aged ≤40 years old (27, 72.97%), worked outdoors (30, 81.08%), and had contact with animals (22, 59.46%). More than half of the 37 co-exposed individuals were aged ≤40 years old (25, 67.57%) and had contact with animals (26, 70.27%), and a high proportion of them were male (33, 89.19%) and worked outdoors (33, 89.19%) (Table 2, Supplementary Table S5). This suggests that certain human activities or environments may increase the likelihood of exposure to different arboviruses. Interestingly, of the twelve individuals who had co-exposure to ZIKV and any other TBV(s) (Supplementary Table S6).

Table 2.

Personal information of the 37 individuals with neutralizing activities different arboviruses or co-exposure to arboviruses.

| Characteristics | Individuals with neutralizing activities |

Individuals with co-exposure to multiple arboviruses |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 37) | (n = 37) | |

| Age | ||

| Median (IQR) | 36 (34–41) | 38 (34–43) |

| >40 | 10, 27.03% | 12, 32.43% |

| ≤40 | 27, 72.97% | 25, 67.57% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 29, 78.38% | 33, 89.19% |

| Female | 8, 21.62% | 4, 10.81% |

| Jobsa | ||

| Outdoor | 30, 81.08% | 33, 89.19% |

| Indoor | 7, 18.92% | 4, 10.81% |

| Animal contactb | ||

| Yes | 22, 59.46% | 22, 59.46% |

| No | 15, 40.54% | 15, 40.54% |

Humans from Pakistan were divided into the “Indoor job” group (bankers, doctors, governors, housewives, nurses, freelancers, and teachers) and the “Outdoor job” group (merchants, farmers, laborers, and shopkeepers).

Contacts with animals were recorded, such as cats, dogs, cows, goats, sheep, horses, rabbits, chickens, parrots, and pigeons.

4. Discussion

Arbovirus-associated epidemics remain a serious public health threat in Pakistan (Mostafavi et al., 2021). Approximately 85% of viral infectious diseases were caused by arboviruses, including CHIKV, DENV, West Nile virus (WNV), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), CCHFV, and ZIKV (Fazal and Hotez, 2020). CCHFV has caused outbreaks and epidemics since 1976 (Yousaf et al., 2018) and has become a major public health challenge due to its high annual mortality rate (Atif et al., 2017). However, infections with other vector-borne viruses have rarely been reported from Pakistan, probably because of the limited knowledge of novel viruses and inadequate pathogen surveillance. Punjab Province, locating nearby Xinjiang, China and adjacent to India, is an important region with the most advanced industry and agriculture in Pakistan. Faisalabad is a northeastern city in the province of Punjab. The local population there mostly engaged in open-air agriculture and animal husbandry, thus having increasing risks of exposure to viruses vectored by arthropods such as ticks and mosquitoes, as well as animal hosts infected with arthropods. To understand the significant threat posed by these vector-borne viruses and prepare for emerging infections, it is important to investigate the prevalence of vector-borne viruses among humans in places like Punjab in Pakistan.

This study investigated the seroprevalence of TBVs in healthy individuals from Faisalabad, Punjab, including SFTSV and CCHFV, which have previously been shown to be prevalent in Pakistan (Atif et al., 2017; Zohaib et al., 2020b), and also in Xinjiang, China (Zhang et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2019), and TAMV and KSIV, which are also TBVs of potential medical significance found in the countries closed to Pakistan like Turkey, Kyrgyzstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan since the 1970s (Lvov et al., 1976a, 1976b). In a recent study, the seroprevalence of SFTSV was found to be as high as 46.7% among the healthy population of four provinces (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, Sindh, and Balochistan) during 2016–2017. Among the four provinces, Punjab had the highest rate (51.8%), and 22 cases (2.5%) showed neutralizing activity against SFTSV, suggesting a high threat of SFTSV infection (Zohaib et al., 2020b). Our study found a high SFTSV seroprevalence rate (17.38%) confirmed by neutralization in 2019 from Faisalabad, Punjab, indicating a continuing threat of SFTSV infection in Punjab even two years later. Human cases of CCHF have been reported in Pakistan and Xinjiang, China. Around the time of Eid-ul-Azha each year in Pakistan, human infections with CCHFV have always been identified due to the tradition of slaughtering and trading livestock (Atif et al., 2017). Although very few cases have been reported since 2005, CCHFV has been detected and isolated from ticks collected from Xinjiang, China (Guo et al., 2017). Our study showed a high seroprevalence rate (7.59%) of CCHFV in 2019, which is approximately two times higher than that in 2016–2017 in humans in Punjab, Pakistan (Zohaib et al., 2020a), suggesting that the threat of CCHFV infection may be increasing and that more attention needs to be paid to this virus.

TAMV and KSIV have not been previously discovered in Pakistan. However, the serologic responses to these two TBVs may suggest the presence of other related viruses, as neutrtalizing activities were not detected from the TAMV or KSIV antibody-positive serum samples. Similarly, in the previous study (Zohaib et al., 2020b) and also in our study, the presence of GTV, the virus related to SFTSV, was suggested by identifying neutralizing antibodies specific to GTV in samples that were positive for SFTSV antibodies. We found at least four individuals (S171, S316, S789, and S314) were exposed to GTV other than SFTSV. It suggested the need to investigate GTV epidemiology in ticks, animals, and human patients, and that there may be other viruses related to the known existing arboviruses present in Pakistan. The mosquito-borne ZIKV has been spreading worldwide for more than five years. Although clinical infection with ZIKV has not been identified, human serologic exposure to this virus in Pakistan could be traced back to 1983 (Darwish et al., 1983a). Here, we confirmed human exposure to ZIKV as indicated by the seroprevalence and neutralizing antibodies, suggesting that ZIKV was prevalent there and its impact on humans was underestimated. Taken together, our results reveal the complexity of the arboviruses that are prevalent in Pakistan and have caused infections in the local population. However, these infections probably went unrecognized due to the presence of asymptomatic or mild symptoms, such as infection with SFTSV (Huang et al., 2017) and ZIKV (Heymann et al., 2016; Mlakar et al., 2016), and the inadequate disease surveillance in the country (WHO, 2022).

We discussed the potential of age, gender, occupation, and animal contact in influencing seroprevalence and antibody response levels to each of the viruses tested. The results showed that individuals aged <40 were associated with a higher risk of SFTSV exposure. Males and outdoor workers were at higher risk for TAMV exposure. In addition, stronger antibody responses to SFTSV and CCHFV were found to be significantly associated with individuals aged >40. Males and those who worked outdoors and had no contact with animals had a stronger response to SFTSV, but this was in contrast to the results of the antibody response to ZIKV in the individual groups analyzed (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S3). These results may indicate a different risk of infection or exposure to arboviruses in people living in different environments and performing different activities. Further in-depth studies with more samples are needed to clarify the risk factors associated with TBV and MBV.

The high risk of arbovirus infection has also been suggested by co-exposure to two or three different viruses. Co-infection with the mosquito-borne CHIKV and DENV was found in 11.8% of 590 dengue-positive samples in Pakistan, suggesting a common transmission pathway for mosquito-borne viruses by mosquitoes could lead to co-infection of these viruses (Raza et al., 2021). A previous study found serologic exposure to seven different TBVs in humans from Pakistan, but the occurrence of co-exposure was not addressed (Darwish et al., 1983b; Guo et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2019; Zohaib et al., 2020a; Zohaib et al., 2020b). Here, co-exposure was suggested by the identification of the three individuals (S10, S448, and S133) with neutralization to two different viruses of distinct taxonomy, which should not have serologic correlations (SFTSV-CCHFV and CCHFV-ZIKV). This was expected because the prevalence of CCHFV and SFTSV has been suggested in Pakistan based on the serologic evidence among humans in Punjab province (Zohaib et al., 2020a, 2020b). In addition, in Xinjiang, China, that borders Pakistan, CCHFV prevalence among ticks and human exposure and infection with CCHFV has been suggested for years (Zhang et al., 2018), while SFTSV infection via tick bite was discovered from a tourist there (Zhu et al., 2019). The co-exposure to these viruses suggested that arboviruses may have common routes of transmission to humans in Pakistan. We found that most of the people having neutralization or co-exposure to multiple arboviruses were from Faisalabad, Pakistan (Table 2, Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). This raised the need for further epidemiologic investigation in and around the village to better understand the common pathways of arbovirus spillover to humans.

One limitation of this study is that serum sample collection was limited in Faisalabad, Punjab, which may not represent a landscape of seroprevalence of different arboviruses among people in Pakistan. Nevertheless, the results still suggested that there have been arbovirus exposure occurred and also revealed co-exposure in humans in Pakistan, suggesting the need of increasing attention to Faisalabad. The results would also benefit performing further epidemiological surveys of arboviruses in expanding areas of Pakistan by collecting larger sizes of samples. Moreover, due to the limit of sample sizes, antibodies against only six arboviruses were investigated. Molecular detection of viral RNA were not carried out with these serum samples, because all samples were from healthy people instead of febrile patients.

5. Conclusion

This study established LIPS assays for detecting antibodies against arboviruses, and revealed substantial seroprevalence of these viruses among humans in Pakistan. Our results suggested the prevalence of arboviruses in Pakistan based on the serologic evidence, and assessed human exposure to arboviruses in Pakistan. The findings indicated the presence of other viruses of serologic correlations to arboviruses tested, and exhibited a high risk of having exposure to different arboviruses among humans in Pakistan. This risk needs to be further evaluated and monitored by improving health surveillance for emerging arboviral diseases there.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Wuhan Institute of Virology, CAS (Approval Number: WIVH33202102), and of the Islamia University of Bahawalpur (REC. BEC No. 05-2021-21/2) in Pakistan. All participants gave written informed consent.

Author contributions

Shengyao Chen: formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing. Muhammad Saqib: investigation, resources, visualization. Hafiz sajid Khan, Usman Ali Ashfaq, Muhammad Khalid Mansoor, Abulimti Moming, Jing Liu: investigation, visualization. Yuan Bai: formal analysis, investigation, visualization. Min Zhou, Saifullah Khan Niazi, Qiaoli Wu, Shuang Tang, Muhammad Hassan Sarfraz, Aneela Javed, Sumreen Hayat, Mohsin Khurshid, Iahtasham Khan, Muhammad Ammar Athar, Zeeshan Taj, Bo Zhang: project administration, resources, supervision. Awais-Ur-Rahman Sial: investigation, resources, Supervision. Ali Zohaib: project administration, resources, supervision, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing. Shu Shen, Fei Deng: funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Conflict of interest

Professor Fei Deng and Professor Bo Zhang are editorial board members for Virologica Sinica and were not involved in the editorial review or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Programme of China [Grant Number 2021YFC2300900, 2022YFC2302700], International Partnership Programme of the Bureau of International Cooperation, Chinese Academy of Sciences [Grant Number 153B42KYSB20200013], National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant Number U22A20363], and Biological Resources Programme, Chinese Academy of Sciences [Grant Number KFJ-BRP-017-74].

We would like to thank all team members of the National Virus Resource Center for their help in the experiment and for preserving the serum samples. We would like to thank Prof. Linfa Wang from Duke-National University of Singapore Medical College and Prof. Peng Zhou from Wuhan Institute of Virology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for kindly providing the technical support to establish the LIPS assay.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virs.2024.04.001.

Contributor Information

Fei Deng, Email: df@wh.iov.cn.

Ali Zohaib, Email: ali.zohaib@iub.edu.pk.

Shu Shen, Email: shenshu@wh.iov.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Atif M., Saqib A., Ikram R., Sarwar M.R., Scahill S. The reasons why Pakistan might be at high risk of Crimean Congo haemorrhagic fever epidemic; a scoping review of the literature. Virol. J. 2017;14:63. doi: 10.1186/s12985-017-0726-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awan U.A., Zahoor S., Ayub A., Ahmed H., Aftab N., Afzal M.S. COVID-19 and arboviral diseases: another challenge for Pakistan's dilapidated healthcare system. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93:4065–4067. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badar N., Salman M., Ansari J., Aamir U., Alam M.M., Arshad Y., Mushtaq N., Ikram A., Qazi J. Emergence of chikungunya virus, Pakistan, 2016-2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:307–310. doi: 10.3201/eid2602.171636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Zhang Y., Su Z., Tang S., Wang J., Wu Q., Yang J., Moming A., Zhang Y., Bell-Sakyi L., Sun S., Shen S., Deng F. Discovery of tick-borne Karshi virus implies misinterpretation of the tick-borne encephalitis virus seroprevalence in Northwest China. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.872067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum F., Wisseman Cl J., Casals J. Tick-borne viruses of West Pakistan. 3. Dera Ghazi Khan virus, a new agent isolated from Hyalomma dromedarii ticks in the D. G. Khan District of West Pakistan. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1970;92(3):195–196. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum F., Wisseman Cl J., Traub R. Tick-borne viruses of West Pakistan. I. Isolation and general characteristics. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1970;92(3):180–191. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbelo P.D., Chaturvedi A., Notkins A.L., Gunti S. Luciferase-based detection of antibodies for the diagnosis of HPV-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Diagnostics (Basel) 2019;9:89. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics9030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt A.M., Siddique S., Gardner L.M., Sarkar S., Lancelot R., Qamar R. Zika virus in Pakistan: the tip of the iceberg? Lancet Global Health. 2016;4:e913–e914. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt M.H., Safdar A., Amir A., Zaman M., Ahmad A., Saleem R.T., Misbah S., Khan Y.H., Mallhi T.H. Arboviral diseases and COVID-19 coincidence: challenges for Pakistan's derelict healthcare system. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93:6465–6467. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Xu M., Wu X., Bai Y., Shi J., Zhou M., Wu Q., Tang S., Deng F., Qin B., Shen S. A new luciferase immunoprecipitation system assay provided serological evidence for missed diagnosis of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Virol. Sin. 2022;37:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.virs.2022.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai S., Zhang T., Zhang Y., Wang H., Deng F. Zika virus baculovirus-expressed virus-like particles induce neutralizing antibodies in mice. Virol. Sin. 2018;33:213–226. doi: 10.1007/s12250-018-0030-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai S., Zhang Y., Zhang T., Zhang B., Wang H., Deng F. Establishment of baculovirus-expressed VLPs induced syncytial formation assay for flavivirus antiviral screening. Viruses. 2018;10:365. doi: 10.3390/v10070365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwish M., Hoogstraal H., Roberts T., Ahmed I., Omar F. A sero-epidemiological survey for certain arboviruses (Togaviridae) in Pakistan. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1983;77:442–445. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwish M.A., Hoogstraal H., Roberts T.J., Ghazi R., Amer T. A sero-epidemiological survey for Bunyaviridae and certain other arboviruses in Pakistan. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1983;77(4):446–450. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazal O., Hotez P.J. NTDs in the age of urbanization, climate change, and conflict: Karachi, Pakistan as a case study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo R., Shen S., Zhang Y., Shi J., Su Z., Liu D., Liu J., Yang J., Wang Q., Hu Z., Zhang Y., Deng F. A new strain of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus isolated from Xinjiang, China. Virol. Sin. 2017;32:80–88. doi: 10.1007/s12250-016-3936-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymann D.L., Hodgson A., Sall A.A., Freedman D.O., Staples J.E., Althabe F., Baruah K., Mahmud G., Kandun N., Vasconcelos P.F.C., Bino S., Menon K.U. Zika virus and microcephaly: why is this situation a PHEIC? Lancet. 2016;387:719–721. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00320-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D., Jiang Y., Liu X., Wang B., Shi J., Su Z., Wang H., Wang T., Tang S., Liu H., Hu Z., Deng F., Shen S. A cluster of symptomatic and asymptomatic infections of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome caused by person-to-person transmission. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017;97:396–402. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M.A., Imtiaz K., Shafaq H., Farooqi J., Hassan M., Zafar A., Long M.T., Barr K.L., Khan E. Screening for arboviruses in healthy blood donors: experience from Karachi, Pakistan. Virol. Sin. 2022;37:774–777. doi: 10.1016/j.virs.2022.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lvov D., Sidorova G., Gromashevsky V., Kurbanov M., Skvoztsova L., Gofman Y., Berezina L., Klimenko S., Zakharyan V., Aristova V., Neronov V.M. Virus “Tamdy”--a new arbovirus, isolated in the Uzbee S.S.R. and Turkmen S.S.R. from ticks Hyalomma asiaticum asiaticum Schulee et Schlottke, 1929, and Hyalomma plumbeum plumbeum Panzer, 1796. Arch. Virol. 1976;51(1–2):15–21. doi: 10.1007/BF01317830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lvov D., Neronov V.M., Gromashevsky V., Skvortsova T., Berezina L., Sidorova G., Zhmaeva Z., Gofman Y., Klimenko S., Fomina K. “Karshi” virus, a new flavivirus (Togaviridae) isolated from Ornithodoros papillipes (Birula, 1895) ticks in Uzbek S.S.R. Arch. Virol. 1976;50(1–2):29–36. doi: 10.1007/BF01317998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlakar J., Korva M., Tul N., Popovic M., Poljsak-Prijatelj M., Mraz J., Kolenc M., Resman Rus K., Vesnaver Vipotnik T., Fabjan Vodusek V., Vizjak A., Pizem J., Petrovec M., Avsic Zupanc T. Zika virus associated with microcephaly. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;374:951–958. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moming A., Shen S., Fang Y., Zhang J., Zhang Y., Tang S., Li T., Hu Z., Wang H., Zhang Y., Sun S., Wang L.F., Deng F. Evidence of human exposure to Tamdy virus, Northwest China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021;27:3166–3170. doi: 10.3201/eid2712.203532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moming A., Bai Y., Chen S., Wu Q., Wang J., Jin J., Tang S., Sun S., Zhang Y., Shen S., Deng F. Epidemiological surveys revealed the risk of tick-borne Tamdy virus spillover to hosts. Infect. Dis. (Lond.) 2023;18:1–7. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2023.2270677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafavi E., Ghasemian A., Abdinasir A., Nematollahi Mahani S.A., Rawaf S., Salehi Vaziri M., Gouya M.M., Minh Nhu Nguyen T., Al Awaidy S., Al Ariqi L., Islam M.M., Abu Baker Abd Farag E., Obtel M., Omondi Mala P., Matar G.M., Asghar R.J., Barakat A., Sahak M.N., Abdulmonem Mansouri M., Swaka A. Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region, 2001-2018. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2021;11:1286–1300. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2021.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza F.A., Javed H., Khan M.M., Ullah O., Fatima A., Zaheer M., Mohsin S., Hasnain S., Khalid R., Salam A.A. Dengue and Chikungunya virus co-infection in major metropolitan cities of provinces of Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: a multi-center study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S., Duan X., Wang B., Zhu L., Zhang Y., Zhang J., Wang J., Luo T., Kou C., Liu D., Lv C., Zhang L., Chang C., Su Z., Tang S., Qiao J., Moming A., Wang C., Abudurexiti A., Wang H., Hu Z., Zhang Y., Sun S., Deng F. A novel tick-borne phlebovirus, closely related to severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus and Heartland virus, is a potential pathogen. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018;7:95. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0093-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waris A., Anwar F., Asim M., Bibi F. Is the bell ringing for another outbreak of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Pakistan? Public Health Pract. (Oxf.) 2022;4 doi: 10.1016/j.puhip.2022.100319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Communicable disease surveillance and response - Pakistan, 2022. 2022. http://www.emro.who.int/pak/programmes/communicable-disease-a-surveillance-response.html (Accessed Jul 2022)

- Yadav P.D., Malhotra B., Sapkal G., Nyayanit D.A., Deshpande G., Gupta N., Padinjaremattathil U.T., Sharma H., Sahay R.R., Sharma P., Mourya D.T. Zika virus outbreak in Rajasthan, India in 2018 was caused by a virus endemic to Asia. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019;69:199–202. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf M., Ashfaq U., Anjum K., Fatima S. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) in Pakistan: the “bell” is ringing silently. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2018;28(2):93–100. doi: 10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.2018020593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Shen S., Shi J., Su Z., Li M., Zhang W., Li M., Hu Z., Peng C., Zheng X., Deng F. Isolation, characterization, and phylogenic analysis of three new severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome bunyavirus strains derived from Hubei Province, China. Virol. Sin. 2017;32:89–96. doi: 10.1007/s12250-017-3953-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Shen S., Fang Y., Liu J., Su Z., Liang J., Zhang Z., Wu Q., Wang C., Abudurexiti A., Hu Z., Zhang Y., Deng F. Isolation, characterization, and phylogenetic analysis of two new Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus strains from the northern region of Xinjiang province, China. Virol. Sin. 2018;33:74–86. doi: 10.1007/s12250-018-0020-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Yin F., Moming A., Zhang J., Wang B., Gao L., Ruan J., Wu Q., Wu N., Wang H., Deng F., Lu G., Shen S. First case of laboratory-confirmed severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome disease revealed the risk of SFTSV infection in Xinjiang, China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019;8:1122–1125. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1645573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohaib A., Saqib M., Athar M.A., Hussain M.H., Sial A.U., Tayyab M.H., Batool M., Sadia H., Taj Z., Tahir U., Jakhrani M.Y., Tayyab J., Kakar M.A., Shahid M.F., Yaqub T., Zhang J., Wu Q., Deng F., Corman V.M., Shen S., Khan I., Shi Z.L. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in humans and livestock, Pakistan, 2015-2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:773–777. doi: 10.3201/eid2604.191154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohaib A., Zhang J., Saqib M., Athar M.A., Hussain M.H., Chen J., Sial A.U., Tayyab M.H., Batool M., Khan S., Luo Y., Waruhiu C., Taj Z., Hayder Z., Ahmed R., Siddique A.B., Yang X., Qureshi M.A., Ujjan I.U., Lail A., Khan I., Sajjad Ur R., Zhang T., Deng F., Shi Z., Shen S. Serologic evidence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus and related viruses in Pakistan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:1513–1516. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.190611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.