Abstract

The infection caused by porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) is associated with high mortality in piglets worldwide. Host factors involved in the efficient replication of PEDV, however, remain largely unknown. Our recent proteomic study in the virus-host interaction network revealed a significant increase in the accumulation of CALML5 (EF-hand protein calmodulin-like 5) following PEDV infection. A further study unveiled a biphasic increase of CALML5 in 2 and 12 h after viral infection. Similar trends were observed in the intestines of piglets in the early and late stages of the PEDV challenge. Moreover, CALML5 depletion reduced PEDV mRNA and protein levels, leading to a one-order-of-magnitude decrease in virus titer. At the early stage of PEDV infection, CALML5 affected the endosomal trafficking pathway by regulating the expression of endosomal sorting complex related cellular proteins. CALML5 depletion also suppressed IFN-β and IL-6 production in the PEDV-infected cells, thereby indicating its involvement in negatively regulating the innate immune response. Our study reveals the biological function of CALML5 in the virology field and offers new insights into the PEDV-host cell interaction.

Keywords: Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), EF-hand protein calmodulin-like 5 (CALML5), Late endosomes, Innate immune response

Highlights

-

•

PEDV infection increases the accumulation of CALML5 both in vivo and in vitro.

-

•

CALML5 promotes PEDV virion internalization to influence late-endosome synthesis by regulating ESCRT.

-

•

CALML5 suppresses the production of IFN-β by targeting RIG-I-MAVS pathway.

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses are single-stranded RNA viruses with a capsular membrane. They have a 26- to 32-kb-long genome and harbor seven conserved coronavirus genes. Of those genes, ORF1a/b encodes viral nonstructural proteins, and the remaining viral gene encodes spike protein (S), nucleocapsid protein (N), membrane glycoprotein (M), and envelope protein (E), which are structural proteins (Mcbride et al., 2014). The porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) (family Coronaviridae; order Nidovirales) primarily infects the small intestinal epithelial cells of newborn piglets and causes diarrhea, which then results in dehydration and death. PEDV was first discovered in Europe in the 1970s (Lee, 2015) and introduced to Asia in 1980, where it spread rapidly. The 2013 PEDV pandemic in the United States led to enormous losses to the swine industry (Zhang H. et al., 2023). Unfortunately, as mutant strains emerged, the previous inactivated vaccines and attenuated vaccines could not offer effective immune protection against the new strains (Zhang W. et al., 2023). In the past two decades, highly pathogenic variant PEDV strains have resulted in almost 100% mortality in newborn piglets.

In coronavirus, internalization and uncoating following membrane fusion depend on endosomal pathways, such as endosomal acidification (Jurgeit et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2023) and endosome lysosome fusion (Yang et al., 2022). The multivesicular body (MVB), a specialized late endosome (LE) that particularly expresses Rab7, is involved in coronavirus replication (Sun et al., 2021). Rab7 critically regulates endosome transformation, facilitating movement along microtubules and acidification. LEs are crucial for vesicle biogenesis and sorting of ubiquitinated proteins for lysosomal degradation through the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) system (Hu et al., 2015). ESCRT has more than 20 different proteins organized into five complexes: ESCRT-0, I, II, III, and VPS4. Notably, enveloped retroviruses (Meng et al., 2020) and RNA viruses (e.g., hepatitis C virus) (Barouch-Bentov et al., 2016; Deng et al., 2022) manipulate cellular ESCRT proteins to induce budding and fission at the plasma membrane for the release of viral particles from infected cells. The SARS-CoV-2 virus-like particle S protein can recruit ESCRT to promote self-assembly, which increases the effectivity of mRNA vaccine (Hoffmann et al., 2023).

Innate immunity serves as the initial line of defense against virus infection. In the PEDV, host pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), specifically cytosolic retinoic acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I)-like receptors, activate this defense by recognizing and interacting pathogen-associated molecular patterns (Temeeyasen et al., 2018; Qian et al., 2019). This interaction subsequently triggers the mitochondrial antiviral signaling pathway, thereby activating the phosphorylation of the interferon regulatory transcription factor (p-IRF3). Consequently, p-IRF3 modulates the expression of type-I interferons, such as interferon-beta (IFN-β) (Hou et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2015).

CALML5 is an EF-hand Ca2+ binding protein that belongs to the family of calmodulin-like (CML) proteins. It is a novel diagnostic marker for breast cancer (Kanamori et al., 2023). Additionally, CALML5 is involved in cell differentiation and tumorigenesis (Sun et al., 2015; Bu et al., 2023). In plant cells, it is involved in suppressing plant virus induced RNA silencing (Li et al., 2017). RNA silencing is vital for plant immunity, and CML protein serve as an agent for viral recognition in plant cells (Nakahara et al., 2012). On the other hand, according to report in animal virus infection, calmodulin-like protein 6 (CALML6) complexes with IRF3 in a phosphorylation-dependent manner and sequesters IRF3 in the cytoplasm, thus downregulating type I IFN (Wang et al., 2019). Moreover, CALML6 negatively regulates the NF-κB signaling pathway, which is vital for maintaining the balance of innate immune responses (Sheng et al., 2020). The role of CALML5 in viral infection has not been reported. A previously conducted proteomic screen unveiled that PEDV infection significantly increases CALML5 levels, thus suggesting the crucial involvement of this protein in PEDV replication. This study offers preliminary insights into the mechanistic aspects of CALML5 in PEDV infection.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cells, viruses, reagents, and antibodies

Vero E6 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Gibco Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 5% or 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator (all reagents obtained from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) strain Indiana, and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) strain CV777 were reproduced in Vero cells for 48 h. PEDVGS/2020/04 isolated strain was used for animal experiments. Rabbit polyclonal anti-CALML5 (A7808) and mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG (AE005) were from ABclonal (Wuhan, China). Rabbit monoclonal anti-DR5 were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Rabbit Polyclonal anti-RAB7 (ER1802-53) were from HUABIO (Hangzhou, China). Rabbit Anti-Cofilin (5175), Anti-Phospho-Cofilin (3313) were from Cell Signaling Technology (MA, USA). The mouse monoclonal Anti- TSG101 (67381), mouse monoclonal Anti-EEA1 (68065) were from Proteintech. The rabbit IgG were from Beyotime Biotechnology. The mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH, FITC-conjugated goat anti-Mouse antibody, and TRITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody were from Proteintech (Rosemount, IL, USA). Mouse monoclonal anti-PEDV-N was from Alpha Diagnostic International (San Antonio, TX, USA).

2.2. RNA interference (RNAi) and cell viability assay

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting CALML5 (sense: 5′-GAAGCUCAUCUCCCAGUUUTT-3′; antisense: 5′-AAACUGGGAGAUGAGCUUCTT-3′), calmodulin1 (CALM1), TSG101, VPS28, EAP20, MVB12 (Zhang L. et al., 2022), and negative control (NC) siRNA were synthesized by Genepharma (Shanghai, China). Vero E6 cells grown to 50%–60% confluence and transfected with siRNAs (final concentration of 100 nmol/L) using Lipofectamine RNAi MAX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). At 36 h post-transfection, cells were utilized for subsequent experiments.

2.3. CALML5-knockout Vero-E6 cell line screen

The vector pcDNA3.1 was purchased from Clontech. FLAG-tagged CALML5 was synthesized by Shanghai General Biotech and cloned into pcDNA3.1. pLV-Cas9-Puro-U6-gCALML5-1 and pLV-Cas9-Puro-U6-gCALML5-2 were constructed and packaged with VectorBuilder. The single guide RNAs for CALML5 are as follows:

sgCALML5-1: CTGCTCAGGAGTCAGCTCAC

sgCALML5-2: GTCGCCGTCGCTATCAAACT

Vero E6 cells grown to 70%–90% confluence and transfected with recombinant plasmid or empty vector using Lipofectamine™ LTX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). At 24 h post-transfection, discard the old DMEM and add 5 μg/mL puromycin, and exchange the DMEM with 5 μg/mL puromycin every 2 days. After screening for two weeks, the survival cells were selected and further verified by Western Bolt.

2.4. Total RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

According to the manufacturer's protocol, total RNA was extracted from cells cultured and animal tissue using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and reverse transcription was conducted using One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). From three independent experiments, transcription levels for different genes were calculated using a Bio-Rad PCR instrument (Hercules, CA, USA) and the SYBR green qPCR master mix (Vazyme, Q712-03). The RNA levels of viral genes were normalized by GDAPH mRNA, and relative quantities (RQ) of mRNA accumulation were evaluated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

2.5. Western blot analysis

Cells were washed in ice-cold PBS, then lysed and harvested in Radio-Immunoprecipitation Assay buffer (RIPA buffer) in the presence of protease inhibitor cocktail. Protein concentrations were measured using a BCA Kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China), and separated by SDS-PAGE on 12.5% gels (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), then electroblotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membranes were incubated with the primary antibody overnight, and the blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at 25 °C. Finally, the blots were exposed using an ECL detection system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and Western blotting bands were quantified according to intensity using ImageJ software.

2.6. Measurement of cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations

The intracellular Ca2+ concentrations were measured with Fluo-4AM (S1060, Beyotime, China). Briefly, cells seeded (5 × 104 cells/well) in 96-well plate were washed three times with PBS and loaded with 100 μL of Fluo-4AM (diluted in PBS) for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were then washed with PBS three times and cultured another 30 min at 37 °C. Vero E6 cells were transfected with siCALML5 or siNC for 48 h, and then the knockdown cells were loaded with Fura-4AM (diluted in PBS) for 1 h at 37 °C. To measure the intracellular Ca2+ concentrations in dithizone (DTZ) blocking cells, Vero E6 cells were deal with DTZ or DMSO for 1 h, and then cells were loaded with Fura-4AM (diluted in PBS) for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were infected with PEDV at an MOI of 1. Finally, the fluorescent absorbance values of cells were detected at intervals with a fluorescent microplate reader.

2.7. Immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for IFN-β

The IFN-β level of Huh-7 cell determined via the human IFN-β ELISA Kit (RK01630; ABclonal Technology Co., Ltd., China). The human IFN-β ELISA Kit used as previous report (Shi et al., 2023). The absorbance was measured using a Microplate plate reader (BioTek, USA) set to 450 nm.

2.8. Immunofluorescence analysis (IFA)

Vero cells transfected with siCALML5 or siNC were grown on microscope coverslips placed in 24-well plates, and were infected with PEDV at an MOI of 5 for 1 h at 37 °C. The virus inoculum was subsequently discarded and washed by PBS three times, then replaced by a normal growth medium. At different hours post infection, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 45 min at 25 °C, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS at 25 °C for 20 min, and the non-specific binding was blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Then the cells were incubated with mouse anti- TSG101 monoclonal antibody (1:200) overnight at 4 °C (The usage of mouse anti-TSG101 monoclonal antibody and mouse anti-EEA1 monoclonal antibody is as the same as mouse anti-PEDV N monoclonal antibody). After being washed three times with PBS, the cells were incubated for 60 min at 25 °C with a FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:500). The cells were again washed three times with PBS, incubated with rabbit anti-CALML5 (1:200) (ab122665, Abcam) overnight at 4 °C, washed three times, incubated for 60 min at 25 °C with a TRITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:500). Finally, the cells were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), and the images were viewed under an ECLIPSE Ni series upright biological microscope (Nikon) (Fluoview 200×).

2.9. In vivo experiment

Newborn specific pathogen-free (SPF) piglets that had not drunk colostrum were obtained and fed special milk to 3 days old. Then piglets were challenged with 3 mL 105 TCID50 PEDV or DMEM by adding the virus to the milk. Piglets were humanely slaughtered at the appointed time and obtained the jejunum. The cell protein and mRNA samples were obtained by grinding the tissue with liquid nitrogen which then were detected by Western blot and qRT-PCR. All piglets were randomly allocated into 5 groups with 3 piglets per group.

2.10. Statistical analysis

All assays were each repeated three times, and all results were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using Prism Version 9.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Significance was determined by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a two-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple-comparison test. Partial correlation analyses were evaluated using an unpaired Student's t-test. For all analyses, p values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant (∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ns, P > 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. PEDV infection upregulated CALML5 expression both in vivo and in vitro

The proteomic analysis in our previous study (Dong et al., 2023) revealed that the CALML5 protein level was significantly upregulated following PEDV infection. Here, we evaluated the temporal expression of CALML5 in Vero E6 cells and piglets. The endogenous CALML5 level increased at 2 and 12 hours post infection (hpi) in the PEDV-infected Vero cells, compared with the mock-infected cells (Fig. 1A). A similar tendency was observed in the CALML5 mRNA level (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, we infected 2-day-old piglets with the GII serotype PEDV isolated strain GS/2020/04 to evaluate their CALML5 mRNA and protein levels. The CALML5 mRNA level increased at 3 and 12 hpi in the jejunum of the piglets (Fig. 1C), and the CALML5 protein level increased simultaneously (Fig. 1D). In comparison, the mRNA levels of pAPN, a well-recognized host factor critical for PEDV entry, significantly increased at 3 hpi then decreased to the baseline levels (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that PEDV infection specifically augments the CALML5 expression level.

Fig. 1.

The expression of CALML5 during PEDV infection both in vivo and in vitro. A, B The protein and mRNA levels of CALML5 during PEDV infection in Vero E6 cells. Cells were mock infected or infected with PEDV (CV777) at MOI of 1, and then harvested at pointed times. The protein level was analyzed by using Western blotting (WB) with the indicated antibodies (A). The mRNA level was subjected to RT-qPCR analysis for CALML5 (B). C, D Levels of CALML5 mRNA and proteins in jejunum of piglets during PEDV infection. Piglets were challenged with GIIb serotype PEDV isolated strain GS/2020/04 (105 TCID50 in 3 mL DMEM) or DMEM (3 mL) for different times, and the jejunum was obtained. The mRNA and protein levels of CALML5 were analyzed by RT-qPCR (C) and WB (D), respectively, in the tissue samples after cryogenic grinding with liquid nitrogen. Data presented as three independent experiments (means ± SD). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001; ns showed no significant difference.

3.2. CALML5 facilitated the efficient replication of PEDV

To determine the effect of CALML5 on viral replication, siCALML5- or siNC-transfected Vero cells were infected with PEDV at different times. CALML5 knockdown considerably decreased the PEDV-N protein level at 8, 12 and 24 hpi (Fig. 2A), and caused a 10-fold decrease in the virus titer (Fig. 2B). The PEDV mRNA level was also reduced (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, to obtain a solid conclusion of the effect of CALML5 on PEDV infection, we constructed CALML5 knockout cell lines. PEDV replication was significantly suppressed in the CALML5 knockout cells (Fig. 2D). In addition, the levels of transiently expressed FLAG-tagged CALML5 increased the PEDV-N level (Fig. 2E) and virus titer (Fig. 2F). The results demonstrate that CALML5 is a vital host factor for efficient PEDV replication.

Fig. 2.

Effect of knockdown and overexpression of CALML5 on PEDV infection. A–C Vero E6 cells were transfected with siRNA targeting CALML5 (siCALML5) or negative control (siNC), and then infected with PEDV (CV777) at an MOI of 1. Cells were harvested at pointed times. The protein level was analyzed by Western blotting (WB) (A), virus titer was determined using TCID50 with the method of Reed-Muench (B), and the mRNA level of PEDV-N was analyzed by RT-qPCR (C). D CALML5-knockout Vero cells and wild-type Vero cells were infected with 0.1 MOI PEDV (CV777), and then cells were harvested at pointed times. The protein level was analyzed by WB. E, F Vero cells were transfected with empty vector pFLAG or recombinant plasmid pFLAG-tagged CALML5. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were infected with PEDV (CV777) at an MOI of 0.1, and cells were harvested for indicated times. The protein level was analyzed by WB (E). Virus titer was determined using TCID50 with the method of Reed-Muench (F). Data presented as three independent experiments (means ± SD). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001; ns showed no significant difference.

3.3. CALML5 promoted PEDV internalization and virion release

To explore the stage of the PEDV life cycle in which CALML5 participates, we first analyzed whether CALML5 is involved in viral attachment or internalization. CALML5 silencing had no effect on PEDV attachment, but obviously blocked viral internalization, as determined by measuring the baseline PEDV mRNA level by using RT-PCR method (Fig. 3A and B). By contrast, no obvious effect was observed for the silencing of calmodulin1 (CALM1), which is a crucial host factor involved in SARS-CoV-2 replication (Ragia and Manolopoulos, 2020).

Fig. 3.

CALML5 is involved in viral internalization of PEDV. A, B CALML5 participates in PEDV internalization instead of viral attachment. Vero E6 cells were transfected with siCALML5 or siNC, and then infected with PEDV (CV777) at an MOI of 5 at 4 °C for 1 h. In viral attachment test (A), the infected cells were harvested after washing with PBS. In viral internalization test (B), after washing with PBS, cells were incubated at 37 °C for another 1 h. Then the infected cells were washed with PBS and harvested. The mRNA levels of PEDV-N analyzed by RT-qPCR. C Vero cells were pre-treated with rabbit antibody against CALML5 (diluted at 1:100) and DR5 (1:100) or rabbit IgG (1:100) for 2 h. After washing with PBS, cells were infected with PEDV (MOI of 5) at 37 °C for 2 h. The mRNA levels of PEDV-N analyzed by RT-qPCR. D CALML5 is also involved in PEDV release. Vero E6 cells transfected with siCALML5 or siNC and then infected with PEDV (CV777) at MOI of 0.5. PEDV titers in cells (intracellular) and culture fluid (extracellular) were determined by TCID50 assay at different infection times. E Vero E6 cells were transfected with siCALML5 or siNC and then infected with PEDV at MOI of 0.5 for different times, cell samples were collected, and the levels of negative-strand viral RNA (in the presence of CHX at 2 hpi) were analyzed by RT-qPCR. Data presented as three independent experiments (means ± SD). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001; ns showed no significant difference.

Furthermore, Vero cells that pre-treated with the CALML5 antibody were infected with PEDV for two hours, and viral entry was still allowed (Fig. 3C). Antibody to the host factor DR5 can block PEDV attachment (X.Z. Zhang et al., 2022). The effect of CALML5 knockdown on intracellular and extracellular virus titers, where the ratio of extracellular to intracellular viral yields denotes the virion release efficiency, was also determined. The result indicates the possibility of CALML5-influenced viral release (Fig. 3D). The negative-strand RNA level of PEDV was determined by separating translation and RNA replication processes with cycloheximide at 2 h following PEDV infection. No measurable difference in viral RNA levels was observed between the CALML5-knockdown cells and negative control cells (Fig. 3E). Collectively, our results suggest that CALML5 promotes viral internalization and virion release but has no effect on PEDV attachment and RNA transcription.

3.4. CALML5 depressed PEDV infection-induced Ca2+ concentration

We further investigated the mechanism through which CALML5 modulates virus invasion and release. Recent reports indicate that PEDV enters cells primarily through clathrin-mediated endocytosis in a process dependent on low pH (Park et al., 2014). Internalized PEDV virions reach lysosomes via the early endosome-late endosome-lysosome pathway (Wei et al., 2020). Our studies have demonstrated the substantial role of cytoskeleton rearrangement in PEDV entry (Wang et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023). Additionally, the Ca2+ pathway is involved in the entire lifecycle of coronavirus (Bai et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2023). To determine the cellular pathway or stage of action in which CALML5 participates, we conducted further experiments.

First, Ca2+ concentrations in the mock-infected cells and PEDV-infected cells were assessed. The concentration increased in the infected cells (Fig. 4A). After CALML5 was knock-downed in the Vero E6 cells, the Ca2+ concentration reduced to a level closed to that in the mock-infected cells (Fig. 4A). DTZ, an L-type Ca2+ channel inhibitor, inhibits PDCoV replication (Bai et al., 2020). Before PEDV infection, the Vero E6 cells were treated with DTZ and cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels reduced in these DTZ-treated cells (Fig. 4B). DTZ, however, has no effect on CALML5 and Rab7 expression (Fig. 4C). Additionally, we explored whether CALML5 participates in the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of cytoskeletal cofilin in the CALML5-knockdown cells. Our results indicate that CALML5 does not influence the cytoskeleton at the early PEDV infection stage (Fig. 4D, left).

Fig. 4.

CALML5 promotes the PEDV Infection by regulating late endosome in Vero cells. A, B Intracellular Ca2+ concentration quantified during PEDV infection. Vero E6 cells were transfected with siCALML5 or siNC (A), or Vero cells were pre-treated with DTZ (10 μmol/L) or DMSO (5 μL) for 2 h (B). After washing with PBS, cells were preloaded with Fluo-4AM and infected with PEDV at MOI of 1. The fluorescent absorbance values of cells were detected at different times with a fluorescent microplate reader. C Vero cells were pre-treated DTZ (10 μmol/L) or DMSO (5 μL), washed cells with PBS were challenged to PEDV (CV777) at the MOI of 1. The protein level was analyzed by Western blotting (WB) with the indicated antibodies. D Vero E6 cells were transfected with siCALML5 or siNC, and then mock infected or infected with PEDV at MOI of 1, the protein level was analyzed by WB with the indicated antibodies. E, F Late endosome inhibitor ABMA inhibits PEDV release. Vero cells pre-treated by ABMA (10 μmol/L) for 2 h, and then infected with PEDV at MOI of 0.1 for 24 h. The protein level was analyzed by WB with the indicated antibodies (E) and PEDV titers in cells (intracellular) and culture fluid (extracellular) were determined by TCID50 assay at different infection times (F). G Immunofluorescence assay. The Vero cells were infected with PEDV at MOI of 1, and were then fixed at pointed times and incubated with mouse monoclonal antibody anti-TSG101 (top) and mouse monoclonal antibody anti-EEA1 (bottom), followed by FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (green). Cells were then incubated with rabbit anti-CALML5 followed by TRITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody. Finally, the cells were counterstained with DAPI (blue), and the images were viewed under an ECLIPSE Ni series upright biological microscope (Fluoview 200×). Data presented as three independent experiments (means ± SD). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01.

3.5. CALML5 promoted PEDV infection by regulating the LE in Vero E6 cells

At the early PEDV infection stage, CALML5 knockdown decreased the accumulation of Rab7, a late endosomal marker. By contrast, the levels of EEA1, an early endosomal marker remained unaffected (Fig. 4D, right). AMBA was employed as a late endosomal inhibitor for suppressing late endosomal synthesis. AMBA treatment reduced the levels of the cellular protein Rab7 and the viral protein PEDV-NP, but not of EEA1 (Fig. 4E). We also detected the inhibitory effect of AMBA on virion release (Fig. 4F). These findings demonstrate that CALML5 significantly influences LE synthesis.

Vero E6 cells were mock-infected or infected with PEDV for four hours and fixed. Endogenous CALML5, TSG101 and EEA1 were observed through confocal microscopy. CALML5 was localized in the nucleolus of Vero cells (Fig. 4G). After PEDV infection, CALML5 was translocated to the cytoplasm. Moreover, TSG101 aggregated outside the nucleus (the arrows point out) after viral infection. EEA1 remains in the cytoplasm of the Vero cells regardless of PEDV infection (Fig. 4G).

3.6. CALML5 regulated the LE traffic by targeting ESCRT

We subsequently investigated the mRNA levels of ESCRT function associated host factors in the CALML5-knockdown Vero E6 cells. CALML5 decreased the mRNA levels of components such as TSG101 and VPS28 (Fig. 5A). To investigate whether ESCRT components are required for PEDV infection, a screening assay was conducted using RT-qPCR. Our results showed that PEDV infection caused no significant changes in the mRNA levels of ESCRT components. However, the mRNA levels in the CALML5-knockdown cells and untreated cells are different (Fig. 5B). CALML5 exerts a regulatory effect on the ESCRT complex, especially on ESCRT-I components such as TSG101, VPS28, and MVB12 (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

CALML5 regulates late endosome traffic by targeting ESCRT. A Vero E6 cells were transfected with siCALML5 or siNC, and mRNA levels of ESCRT components were analyzed by RT-qPCR. B Quantitative analysis in mRNA level of ESCRT components. Vero E6 cells were transfected with siCALML5 or siNC, and then mock infected or infected with PEDV at MOI of 1 for indicated times. The mRNA level of ESCRT components was analyzed by RT-qPCR. C The effect of knockdown of ESCRT components on PEDV replication. Vero cells were transfected with siTSG101, siVPS28, siMVB12, siEAP20 or siNC, and then infected with PEDV (CV777) at MOI of 1 for 12 h (left) or 24 h (right). The PEDV-NP level was quantified by Western blotting (WB) and the intensity band ratio of PEDV-NP to GAPDH was analyzed by using ImageJ software (B). Under the same experimental conditions, titers of viruses were measured, as log10 PFU/mL (C). D–F A screened ESCRT components participate in viral internalization of PEDV. Vero E6 cells were transfected with siTSG101, siVPS28, siMVB12, siEAP20 or siNC, and infected with PEDV (CV777) at an MOI of 5 at 4 °C for 1 h. In viral attachment test (D, left), the infected cells were harvested after washing with PBS. In viral internalization test (D, right), after washing with PBS, cells were incubated at 37 °C for another 1 h. Then the infected cells were washed with PBS and harvested. The mRNA levels of PEDV-N were analyzed by RT-qPCR. E A screened ESCRT components are involved in PEDV release. Vero cells transfected with siTSG101, siVPS28, siMVB12, siEAP20 or siNC, and then infected with PEDV at MOI of 0.5 for 12 h. PEDV titers in cells (intracellular) and culture fluid (extracellular) were determined by TCID50 assay at different times. F, G Cytotoxicity of the siRNAs and knockdown efficiency. The Vero cells grown in 96-well plates were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, and the cell viability was evaluated by using CCK8 method (F). Total RNA was extracted and mRNA level was analyzed by RT-qPCR (G). The data were presented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001; ns showed no significant difference.

Among these proteins, we selected a subset of four proteins for further investigation. The results showed that the PEDV NP expression level and virus titer significantly decreased in TSG101, VPS28, and EAP20 knockdown cells at 12 and 24 hpi, which indicated that those proteins functions during the PEDV replication (Fig. 5C). To address the PEDV life cycle stage in which TSG101, VPS28, MVB12, and EAP20 participates, we first analyzed whether these host factors are involved in viral attachment or internalization. These component proteins exhibited no effect on PEDV attachment (Fig. 5D), but TSG101, VPS28, and MVB12 deletion blocked viral internalization. We also evaluated the effect of these components on virion release. Among these proteins, only TSG101 and VPS28 were involved in PEDV release (Fig. 5E). Our findings suggest that CALML5 functions as a regulator of PEDV trafficking through Les, by targeting the ESCRT-I component.

Finally, the silencing of TSG101, VPS28, MVB12, and EAP20 was not cytotoxic to the cells (Fig. 5F). The siRNA efficiency was shown in Fig. 5G.

3.7. CALML5 facilitated PEDV replication in Huh-7 cells

To ascertain the role of CALML5 protein expression in PEDV-infected Huh-7 cells, the cells were initially infected with PEDV and temporal changes in the CALML5 protein were assessed. An obvious upregulation of CALML5 alone was noted at 8 and 12 hpi (Fig. 6A), indicating that the regulatory action mechanism of CALML5 in viral infection possibly differs between the Huh-7 and Vero E6 cells. Additionally, our findings demonstrated a reduction in PEDV-N protein levels at 8 and 12 hpi after CALML5 silencing (Fig. 6B). Moreover, CALML5 silencing caused approximately 5-fold decrease in the virus titer, as determined through the TCID50 assay at different time points (Fig. 6C). To confirm whether LEs were involved in PEDV replication in the Huh-7 cells, these cells were pre-treated with the LE inhibitor AMBA 1 h before PEDV infection and validated its impact on this infection. The results revealed a reduction in Rab7 protein levels after AMBA treatment. However, PEDV replication remained unaffected (Fig. 6D). These results exclude the possibility in which endosomal pathways are essential for PEDV replication in the Huh-7 cells.

Fig. 6.

CALML5 is involved in PEDV replication in Huh-7 cells. A The protein expression of CALML5 during PEDV infection in Huh-7 cells. Huh-7 cells were mock infected or infected with PEDV (CV777) at MOI of 1, cells were harvested at pointed times. The protein level was analyzed by Western blotting (WB). B, C Huh-7 cells were transfected with siCALML5 or siNC, and then infected with PEDV at an MOI of 1, and cells were harvested at pointed times. The protein level was analyzed by WB (B), and virus titer was determined using TCID50 with the method of Reed-Muench (C). D Late-endosome inhibitor ABMA was treated in Huh-7 cells. Huh-7 cells were pre-treated with 10 μmol/L ABMA for 2 h, and then infected with PEDV at MOI of 1 for 24 h. The protein level was analyzed by WB with the indicated antibodies. The data were presented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01.

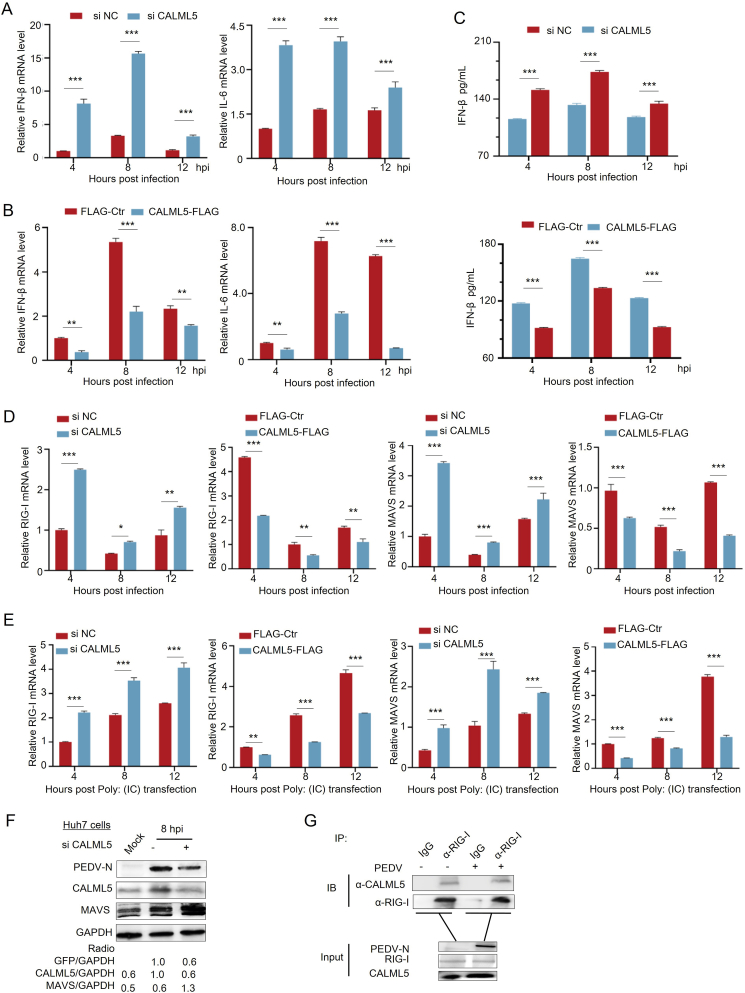

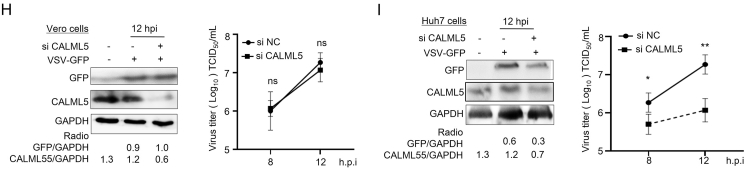

3.8. CALML5 negatively regulated type-I interferon by targeting the RIG-I-MAVS pathway

As noted, EF-hand calcium-binding proteins play a crucial regulatory role in the regulation of virus-induced innate immune responses (Wang et al., 2019; Sheng et al., 2020). Given the limited innate immune response observed in the Vero E6 cells, Huh-7 cells were used to investigate whether CALML5 regulates PEDV-induced type-I interferon expression. CALML5 in Huh-7 cells were knockdown by using siRNA (Fig. 7A) or overexpressed with CALML5-FLAG (Fig. 7B), and then, the cells were infected with PEDV. The mRNA levels of endogenous IFN-β and interleukin-6 (IL-6) at different time points were assessed using the RT-qPCR assay (Fig. 7A and B). The endogenous IFN-β protein were also evaluated (Fig. 7C). Our findings demonstrate that CALML5 downregulates IFN-β mRNA and protein levels, while reducing IL-6 mRNA expression.

Fig. 7.

CALML5 negatively regulates the innate immunity by targeting RIG-I-MAVS pathway. A–D In knockdown group, Huh-7 cells were transfected with siCALML5 or siNC, and then infected with PEDV (CV777) at an MOI of 1, and cells were harvested at pointed times. The mRNA level of IFN-β (A, left), IL-6 (A, right), RIG-I (D, left), and MAVS (D, right) was analyzed by RT-qPCR. In overexpression group, Huh-7 cells were transfected with empty vector pFLAG or recombinant plasmid pFLAG-CALML5 for 24 h, cells were infected with PEDV at an MOI of 0.1, and cells were harvested at pointed times. The mRNA level of IFN-β (B, left), IL-6 (B, right), RIG-I (D, left), and MAVS (D, right) was analyzed by RT-qPCR. The production of endogenous IFN-β was quantified by ELISA kit (C). E Huh-7 cells were treated as above and then transfected with poly (I:C) for 6 h. The cells were harvested at pointed times. The mRNA level of RIG-I and MAVS was analyzed by RT-qPCR. F Huh-7 cells were transfected with siCALML5 or siNC, then infected with PEDV at an MOI of 1 for 8 h. The protein level was analyzed by Western blotting (WB) with the indicated antibodies. G Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assay of CALML5 and RIG-I. Huh-7 cells were mock infected or infected with PEDV at MOI of 0.1 for 12 h, and cell lysates were generated for co-IP assays using immunoglobulin G (IgG) or RIG-I antibody (α-RIG-I), followed by WB to analyze levels of RIG-I and CALML5. H, I Vero cells (H) or Huh 7 cells (I) were transfected with siCALML5 or siNC, then infected with GFP-VSV at a MOI of 0.1 for 12 h, cell lysates were analyzed by WB with specific antibodies to detect CALML5 and VSV-G, with GAPDH as a control (left). Under the same experimental condition, titers of viruses were measured, as log10 PFU/mL (right). Values represent means of triplicates with SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ns showed no significant difference.

Moreover, we elucidated the mechanism through which CALML5 regulates the immune system. PEDV downregulates IFN-β via the RIG-I-MAVS pathway (Shi et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2022). Therefore, RT-qPCR was performed to assess RIG-I and MAVS mRNA levels after PEDV infection or poly(I:C) treatment in the Huh-7 cells with CALML5 knockdown or overexpression (Fig. 7D and E). The RIG-I and MAVS mRNA levels were elevated in the CALML5 knockdown cells, whereas they were depressed in the CALML5 overexpressing cells (Fig. 7D). The poly(I:C) treatment resulted in a similar trend. Furthermore, CALML5 knockdown increases MAVS accumulation (Fig. 7F). A direct interaction was noted between endogenous CALML5 and RIG-I in the Huh-7 cells regardless of viral infection (Fig. 7G). These results indicate that CALML5 negatively regulated IFN-β and IL-6 by targeting RIG-I-MAVS pathway.

To investigate the specific promotion effect of CALML5 on PEDV infection, Vero E6 cells and Huh-7 cells were infected with the VSV-GFP recombinant virus. Our results demonstrate that the decrease in CALML5 level had no effect VSV-GFP replication in the Vero E6 cells (Fig. 7H). However, CALML5 depletion significantly depressed viral replication in the Huh-7 cells (Fig. 7I). These findings demonstrate that CALML5 negatively regulates type-I interferon expression.

4. Discussion

After the COVID-19 pandemic, the invasion and replication of coronaviruses have attracted considerable research attention. According to a recent report, SARS-CoV-2 invades cells by using the lysosome/LE pathway in the process depends on low pH (Kreutzberger et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022). ESCRT can be recruited by the SARS-CoV-2 virus-like particle S protein to promote the self-assembly and budding from the cell surface, and accordingly, the efficacy of mRNA vaccine has been increased (Hoffmann et al., 2023). However, lack of study has reported that PEDV manipulates the LE pathway and ESCRT system. The present study demonstrates that CALML5 facilitates PEDV internalization to influence LE synthesis by regulating ESCRT (Fig. 4, Fig. 5).

CALML5, a member of the calmodulin-like protein family, plays a substantial role in tumor diagnosis and tumor cell differentiation. Its involvement in viral infection processes remains largely unexplored. We investigated the influence of CALML5 on various PEDV infection stages. CALML5 knockdown significantly reduced both internalization and release of PEDV virions. Ca2+ facilitates the replication of coronaviruses, including PEDV (Guo et al., 2023) and PDCoV (Bai et al., 2020). Given that CALML5 functions as a Ca2+-binding protein, we initially assumed whether CALML5 is involved in PEDV replication by modulating the Ca2+ concentration. Our results supported this speculation as well (Fig. 4A and B). Through a series of exclusion experiments, such as the effect of CALML5 on the cytoskeleton rearrangement (Fig. 4D), we found that CALML5 depletion reduces Rab7 expression (Fig. 4C). Considering the concomitant reliance of both PEDV internalization and release processes on the MVB function, coupled with the crucial role of ESCRT in endosomatic cargo screening, we intended to establish a correlation between ESCRT components and CALML5. Our findings demonstrate that CALML5 depletion concomitantly reduces the mRNA levels of the ESCRT components (Fig. 5A and B). Our research unearthed a novel mechanism through which CALML5 regulates the expression of ESCRT component proteins such as TSG101 and VPS28, and its impact on Rab7+ LEs synthesis. The ubiquitinated proteins, which can be degraded by ESCRT in LEs during PEDV internalization, need to be further explored.

Our results indicate a disparity in CALML5 temporal expression between the Huh-7 cells and Vero cells after PEDV infection (Fig. 6). Considering the role of CALML6 in suppressing the innate immunity, CALML5 may promote PEDV replication by suppressing its innate immune response. We found that CALML5 also negatively regulates type-I interferon expression and the inflammatory response by binding to RIG-I (Fig. 7). Those findings revealed a previously unknown function of CALML5 in modulating IFN-β and IL-6 levels, which is activated by targeting the RIG-I-MAVS pathway.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our data confirmed that PEDV infection induces upregulation of CALML5 expression both in vivo and in vitro. Additionally, we discovered that CALML5 is involved in the internalization and release of PEDV virions by regulating ESCRT to influence MVB synthesis. Furthermore, our findings revealed that CALML5 suppresses IFN-β and IL-6 by targeting the RIG-I-MAVS pathway (Fig. 8). Our study significantly advanced the understanding of the role of CALML5 in PEDV internalization and the immune response, offering valuable insights for developing novel therapeutic strategies against PEDV infection.

Fig. 8.

Schematic diagram of CALML5 promotes PEDV replication by regulating late-endosome synthesis and innate immune response. CALML5 promotes PEDV virion internalization to influence late-endosome synthesis by regulating ESCRT in Vero E6 cells (left). Right, CALML5 suppresses the production of IFN-β by targeting RIG-I-MAVS pathway in Huh-7 cells.

Data availability

All the data generated during the current study are included in the manuscript.

Ethics statement

All animal research projects were sanctioned by the Beijing Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee and were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of China Agricultural University (approval number 201206078), and were performed in accordance with Regulations of Experimental Animals of Beijing Authority. Animals were housed with pathogen-free food and water under 12 h light cycle conditions. To reduce stress on other animals, and to avoid panic in living animals, euthanasia was carried out in a soundproof room.

Author contributions

Wen-Jun Tian: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis. Xiu-Zhong Zhang: Software, Methodology, Investigation. Jing Wang: Methodology, Investigation. Jian-Feng Liu: Methodology, Investigation, Supervision. Fu-Huang Li: Investigation, Supervision. Xiao-Jia Wang: Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFD1801100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32172821), and a CAU-Grant for the Prevention and Control of Immunosuppressive Disease in Animals (CAU-G-PCIDA) of the China Agricultural University.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virs.2024.05.006.

Contributor Information

Jian-Feng Liu, Email: liujf@cau.edu.cn.

Fu-Huang Li, Email: lfh5118@126.com.

Xiao-Jia Wang, Email: wangxj@cau.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Bai D., Fang L., Xia S., Ke W., Wang J., Wu X., Fang P., Xiao S. Porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) modulates calcium influx to favor viral replication. Virology. 2020;539:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2019.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch-Bentov R., Neveu G., Xiao F., Beer M., Bekerman E., Schor S., Campbell J., Boonyaratanakornkit J., Lindenbach B., Lu A., Jacob Y., Einav S. Hepatitis C virus proteins interact with the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery via ubiquitination to facilitate viral envelopment. mBio. 2016;7 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01456-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu J., Zhang Y., Niu N., Bi K., Sun L., Qiao X., Wang Y., Zhang Y., Jiang X., Wang D., Ma Q., Li H., Liu C. Dalpiciclib partially abrogates ER signaling activation induced by pyrotinib in HER2(+)HR(+) breast cancer. Elife. 2023;12 doi: 10.7554/eLife.85246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L., Liang Y., Ariffianto A., Matsui C., Abe T., Muramatsu M., Wakita T., Maki M., Shibata H., Shoji I. Hepatitis C virus-induced ROS/JNK signaling pathway activates the E3 ubiquitin ligase itch to promote the release of HCV particles via polyubiquitylation of VPS4A. J. Virol. 2022;96 doi: 10.1128/jvi.01811-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H.J., Wang J., Zhang X.Z., Li C.C., Liu J.F., Wang X.J. Proteomic screening identifies RPLp2 as a specific regulator for the translation of coronavirus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;230 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Feng Y., Zhao X., Qiao S., Ma Z., Li Z., Zheng H., Xiao S. Coronavirus porcine epidemic diarrhea virus utilizes chemokine interleukin-8 to facilitate viral replication by regulating Ca(2+) flux. J. Virol. 2023;97 doi: 10.1128/jvi.00292-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M.A.G., Yang Z., Huey-Tubman K.E., Cohen A.A., Gnanapragasam P.N.P., Nakatomi L.M., Storm K.N., Moon W.J., Lin P.J.C., West A.P., Jr., Bjorkman P.J. ESCRT recruitment to SARS-CoV-2 spike induces virus-like particles that improve mRNA vaccines. Cell. 2023;186:2380–2391.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou F., Sun L., Zheng H., Skaug B., Jiang Q.X., Chen Z.J. MAVS forms functional prion-like aggregates to activate and propagate antiviral innate immune response. Cell. 2011;146:448–461. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.B., Dammer E.B., Ren R.J., Wang G. The endosomal-lysosomal system: from acidification and cargo sorting to neurodegeneration. Transl. Neurodegener. 2015;4:18. doi: 10.1186/s40035-015-0041-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurgeit A., Mcdowell R., Moese S., Meldrum E., Schwendener R., Greber U.F. Niclosamide is a proton carrier and targets acidic endosomes with broad antiviral effects. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori K., Suina K., Shukuya T., Takahashi F., Hayashi T., Hara K., Saito T., Mitsuishi Y., Shimamura S.S., Winardi W., Tajima K., Ko R., Mimori T., Asao T., Itoh M., Kawaji H., Suehara Y., Takamochi K., Suzuki K., Takahashi K. CALML5 is a novel diagnostic marker for differentiating thymic squamous cell carcinoma from type B3 thymoma. Thorac. Cancer. 2023;14:1089–1097. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.14853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzberger A.J.B., Sanyal A., Saminathan A., Bloyet L.M., Stumpf S., Liu Z., Ojha R., Patjas M.T., Geneid A., Scanavachi G., Doyle C.A., Somerville E., Correia R., Di Caprio G., Toppila-Salmi S., Makitie A., Kiessling V., Vapalahti O., Whelan S.P.J., Balistreri G., Kirchhausen T. SARS-CoV-2 requires acidic pH to infect cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2209514119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus: an emerging and re-emerging epizootic swine virus. Virol. J. 2015;12:193. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0421-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.C., Chi X.J., Wang J., Potter A.L., Wang X.J., Yang C.J. Small molecule RAF265 as an antiviral therapy acts against HSV-1 by regulating cytoskeleton rearrangement and cellular translation machinery. J. Med. Virol. 2023;95 doi: 10.1002/jmv.28226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Zhao N., Li Z., Xu X., Wang Y., Yang X., Liu S.S., Wang A., Zhou X. A calmodulin-like protein suppresses RNA silencing and promotes geminivirus infection by degrading SGS3 via the autophagy pathway in Nicotiana benthamiana. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang R., Song H., Wang K., Ding F., Xuan D., Miao J., Fei R., Zhang J. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus 3CL(pro) causes apoptosis and collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential requiring its protease activity and signaling through MAVS. Vet. Microbiol. 2022;275 doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2022.109596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Cai X., Wu J., Cong Q., Chen X., Li T., Du F., Ren J., Wu Y.T., Grishin N.V., Chen Z.J. Phosphorylation of innate immune adaptor proteins MAVS, STING, and TRIF induces IRF3 activation. Science. 2015;347 doi: 10.1126/science.aaa2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcbride R., Van Zyl M., Fielding B.C. The coronavirus nucleocapsid is a multifunctional protein. Viruses. 2014;6:2991–3018. doi: 10.3390/v6082991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng B., Ip N.C.Y., Abbink T.E.M., Kenyon J.C., Lever A.M.L. ESCRT-II functions by linking to ESCRT-I in human immunodeficiency virus-1 budding. Cell Microbiol. 2020;22 doi: 10.1111/cmi.13161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahara K.S., Masuta C., Yamada S., Shimura H., Kashihara Y., Wada T.S., Meguro A., Goto K., Tadamura K., Sueda K., Sekiguchi T., Shao J., Itchoda N., Matsumura T., Igarashi M., Ito K., Carthew R.W., Uyeda I. Tobacco calmodulin-like protein provides secondary defense by binding to and directing degradation of virus RNA silencing suppressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:10113–10118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201628109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.E., Cruz D.J., Shin H.J. Clathrin- and serine proteases-dependent uptake of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus into Vero cells. Virus Res. 2014;191:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian S., Zhang W., Jia X., Sun Z., Zhang Y., Xiao Y., Li Z. Isolation and identification of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and its effect on host natural immune response. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:2272. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragia G., Manolopoulos V.G. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 entry through the ACE2/TMPRSS2 pathway: a promising approach for uncovering early COVID-19 drug therapies. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020;76:1623–1630. doi: 10.1007/s00228-020-02963-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng C., Wang Z., Yao C., Chen H.M., Kan G., Wang D., Chen H., Chen S. CALML6 controls TAK1 ubiquitination and confers protection against acute inflammation. J. Immunol. 2020;204:3008–3018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1901042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Jia X., He Y., Ma X., Qi X., Li W., Gao S.J., Yan Q., Lu C. Immune evasion strategy involving propionylation by the KSHV interferon regulatory factor 1 (vIRF1) PLoS Pathog. 2023;19 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi P., Su Y., Li R., Liang Z., Dong S., Huang J. PEDV nsp16 negatively regulates innate immunity to promote viral proliferation. Virus Res. 2019;265:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B.K., Boxer L.D., Ransohoff J.D., Siprashvili Z., Qu K., Lopez-Pajares V., Hollmig S.T., Khavari P.A. CALML5 is a ZNF750- and TINCR-induced protein that binds stratifin to regulate epidermal differentiation. Genes Dev. 2015;29:2225–2230. doi: 10.1101/gad.267708.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Zhao C., Fu Z., Fu Y., Su Z., Li Y., Zhou Y., Tan Y., Li J., Xiang Y., Nie X., Zhang J., Liu F., Zhao S., Xie S., Peng G. Genome-scale CRISPR screen identifies TMEM41B as a multi-function host factor required for coronavirus replication. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temeeyasen G., Sinha A., Gimenez-Lirola L.G., Zhang J.Q., Pineyro P.E. Differential gene modulation of pattern-recognition receptor TLR and RIG-I-like and downstream mediators on intestinal mucosa of pigs infected with PEDV non S-INDEL and PEDV S-INDEL strains. Virology. 2018;517:188–198. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Tian W.J., Li C.C., Zhang X.Z., Fan K., Li S.L., Wang X.J. Small-Molecule RAF265 as an antiviral therapy acts against PEDV infection. Viruses. 2022;14:2261. doi: 10.3390/v14102261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Huang H., Li D., Zhao C., Li S., Qin P., Li Y., Yang X., Du W., Li W., Li Y. Identification of niclosamide as a novel antiviral agent against porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection by targeting viral internalization. Virol. Sin. 2023;38:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.virs.2023.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Sheng C., Yao C., Chen H., Wang D., Chen S. The EF-hand protein CALML6 suppresses antiviral innate immunity by impairing IRF3 dimerization. Cell Rep. 2019;26:1273–1285.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X., She G., Wu T., Xue C., Cao Y. PEDV enters cells through clathrin-, caveolae-, and lipid raft-mediated endocytosis and traffics via the endo-/lysosome pathway. Vet. Res. 2020;51:10. doi: 10.1186/s13567-020-0739-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Jia Y., Meng Y., Xue Y., Liu K., Li Y., Liu S., Li X., Cui K., Shang L., Cheng T., Zhang Z., Hou Y., Yang X., Yan H., Duan L., Tong Z., Wu C., Liu Z., Gao S., Zhuo S., Huang W., Gao G.F., Qi J., Shang G. SNX27 suppresses SARS-CoV-2 infection by inhibiting viral lysosome/late endosome entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2117576119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Zou C., Peng O., Ashraf U., Xu Q., Gong L., Fan B., Zhang Y., Xu Z., Xue C., Wei X., Zhou Q., Tian X., Shen H., Li B., Zhang X., Cao Y. Global dynamics of porcine enteric coronavirus PEDV epidemiology, evolution, and transmission. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2023;40 doi: 10.1093/molbev/msad052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Li R., Geng R., Wang L., Chen X.X., Qiao S., Zhang G. Tumor susceptibility gene 101 (TSG101) contributes to virion formation of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus via interaction with the nucleocapsid (N) protein along with the early secretory pathway. J. Virol. 2022;96 doi: 10.1128/jvi.00005-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Shen H., Wang M., Fan X., Wang S., Wuri N., Zhang B., He H., Zhang C., Liu Z., Liao M., Zhang J., Li Y., Zhang J. Fangchinoline inhibits the PEDV replication in intestinal epithelial cells via autophagic flux suppression. Front. Microbiol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1164851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.Z., Tian W.J., Wang J., You J.L., Wang X.J. Death receptor DR5 as a proviral factor for viral entry and replication of coronavirus PEDV. Viruses. 2022;14:2724. doi: 10.3390/v14122724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated during the current study are included in the manuscript.