Abstract

Background

Subgingival bacterial colonization and biofilm formation are known to be the main etiology of periodontal disease progression. This biofilm elicits host response and the interaction between host defence mechanisms with plaque microorganisms and their products results in periodontal disease. Host modulatory therapy (HMT) is a form of treatment of periodontitis that focuses on treatment of the host in the host–bacteria interaction. Omega-3 fatty acids have emerged as a potential HMT agent to treat inflammation associated with periodontal disease.

Methods

A total of 60 cases of chronic periodontitis were allocated into two groups; the test group (n = 30) were treated with scaling and root planing (SRP) and given a dietary supplementation of omega-3 fatty acid while the control group were treated with SRP alone. Clinical parameters carried out were plaque index (PI), gingival bleeding index (GBI), pocket probing depth (PPD) and clinical attachment level (CAL) and immunological parameter included interleukin-1β level in saliva at baseline, 3 months and 6 months after therapy.

Results

At 6 months, both the groups showed significant improvements with regards to all clinical and immunological parameters compared to baseline (all p < 0.05). However, test group presented with more favourable statistically significant results.

Conclusion

The use of omega-3 fatty acid as nutraceutical agent to conventional method acted as beneficial therapeutic measures and effective in patients with chronic periodontitis when compared with SRP alone.

Keywords: Omega-3 fatty acid, Periodontitis, Host modulation, Interleukin-1 β

Introduction

Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease of tooth supporting structure that causes loss of clinical attachment as a result of the destruction of the bone and periodontal ligament. The interplay between the host and the microbiologic factors are responsible for the periodontal breakdown. During this process host cells release various inflammatory chemical mediators like Interleukins (ILs), Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and Prostaglandins (PGs).1,2

Periodontal treatment modalities involve surgical or nonsurgical periodontal therapy based on severity of disease. Mechanical and chemotherapeutic methods to disrupt or eliminate microbial biofilm is commonly used as Nonsurgical peridontal treatment (NSPT). However comprehensive mechanical debridement with deep periodontal pockets is difficult to accomplish with non-surgical periodontal therapy such as scaling and root planing (SRP). SRP alone will not eliminate the pathogenic microflora because of inaccessible areas to periodontal instruments hence an adjunctive therapy is mandatory. Various systemic or local antimicrobial/anti-inflammatory agents are the most commonly used methods.3

Periodontitis has also been associated with chronic systemic diseases like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, respiratory tract infections, metabolic syndrome and neurocognitive diseases and impairment.4,5 Pro-inflammatory cell and cytokine-mediated markers of inflammation, including IL-1, IL-6, and Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) play an important role in the development and advancement of periodontitis. These inflammatory markers are also common in many systemic diseases, therefore; management of inflammation associated with periodontitis can positively assist in the progression, morbidity, mortality, and controlling of non-oral systemic diseases.

Host modulatory therapy (HMT) is a form of NSPT that focuses on treatment of the host in the host–bacteria interaction. The therapy focuses to modify the host response in order to reduce tissue destruction and enhance regeneration of lost periodontium. This is achieved through the downregulation of destructive processes of the host inflammatory response and reduction of inflammation, with up-regulation of regenerative processes which aid in periodontal stability.6

Various agents used for this are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, bisphosphate, sub antimicrobial doxycycline, enamel matrix protein, growth factors, and bone morphogenic proteins. Use of omega-3 fatty acids have raised question as to whether or not it could act as a potential HMT agent to treat inflammation associated with periodontal disease.7

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) are synthesized from dietary intake of essential fatty acids. The parent omega-3 fatty acids is alpha-linolenic acid (ALA; C18:3n-3), synthesized in the body to produce long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; C20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; C22:6n-3). Omega-3 PUFA possess the most potent immunomodulatory activities, and among them, those from fish oil, EPA and DHA, are more biologically potent than ALA.8

The inflammatory mediators and cytokines manifest potent pro-inflammatory and catabolic activity and may play a key role in local amplification of the immune response as well as periodontal tissue breakdown. Among the chemical mediators released by the host cells, IL-1 beta is proven to play a major role in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases. IL-1 beta has been demonstrated at increased levels in inflamed gingival tissues and gingival crevicular fluid. It is proven to be the most potent inducers of bone resorption and connective tissue degradation through MMPs gene expression.9

The aim of this study was to use omega 3 fatty acids as an adjunct to SRP in the treatment of chronic periodontitis and to compare clinical and immunological parameters before and after treatment.

Materials and methods

Study protocol and methods

This prospective interventional clinical trial was a multicentric study which were conducted at tertiary care Government hospital at southern and western part of India. The study was designed to compare the effect of omega-3 fatty acid after dietary supplementation after SRP in patients with chronic periodontitis. 60 patients (37 male and 23 female) between 18 and 65 years of age with chronic periodontitis were assessed for eligibility at the Department of Periodontics who came for regular dental check-up. The study was carried out in accordance with the code of ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki-2000). All patients provided written informed consent. Based on the 2017 classification system for periodontal diseases and the conditions, patients diagnosed with Stage III Grade B periodontitis involving of at least 30% and a clinical attachment loss of ≥5 mm were selected along with periodontal pockets with a probing depth ≥4 mm. Patients who had undergone periodontal treatment in last 01 year, antibiotic therapy in the last 90 days, smokers, pregnant or lactating patients, or allergic to polyunsaturated fatty acids were excluded.

Data parameters

Plaque index (PI), Gingival Bleeding index (GBI), Pocket probing depth (PPD) and Clinical attachment loss (CAL) and immunological parameter of Interleukin -1β were recorded at baseline, 03 months and 06 months. Williams graduated probe were used to record all clinical parameters. Change in levels of interleukin-1β in saliva was measured as the primary outcome following intervention. A single operator performed the measurements of all the subjects throughout the study in each centre. All subjects were prescribed omega-3 PUFA tablets as dietary supplement following treatment. Saliva samples were taken at baseline, 03 months and 06 months [Fig. 1]. Change in the levels of interleukin-1β were assessed using ELISA.

Fig. 1.

Sterile tubes containing samples at baseline, 3 and 6 months.

Treatment procedure

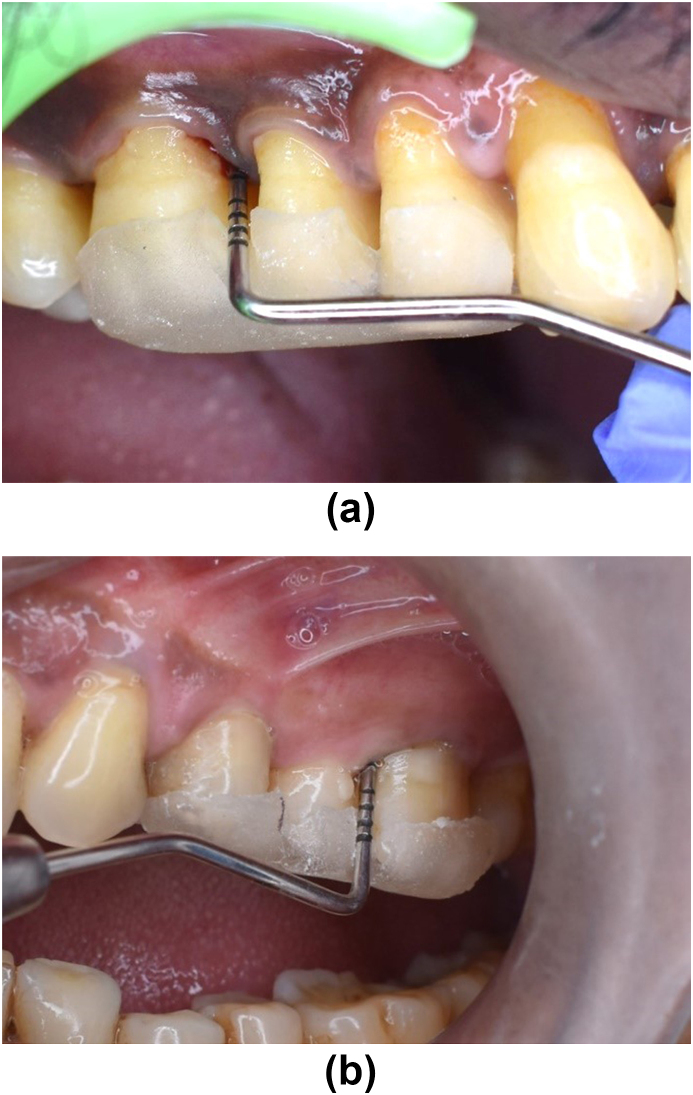

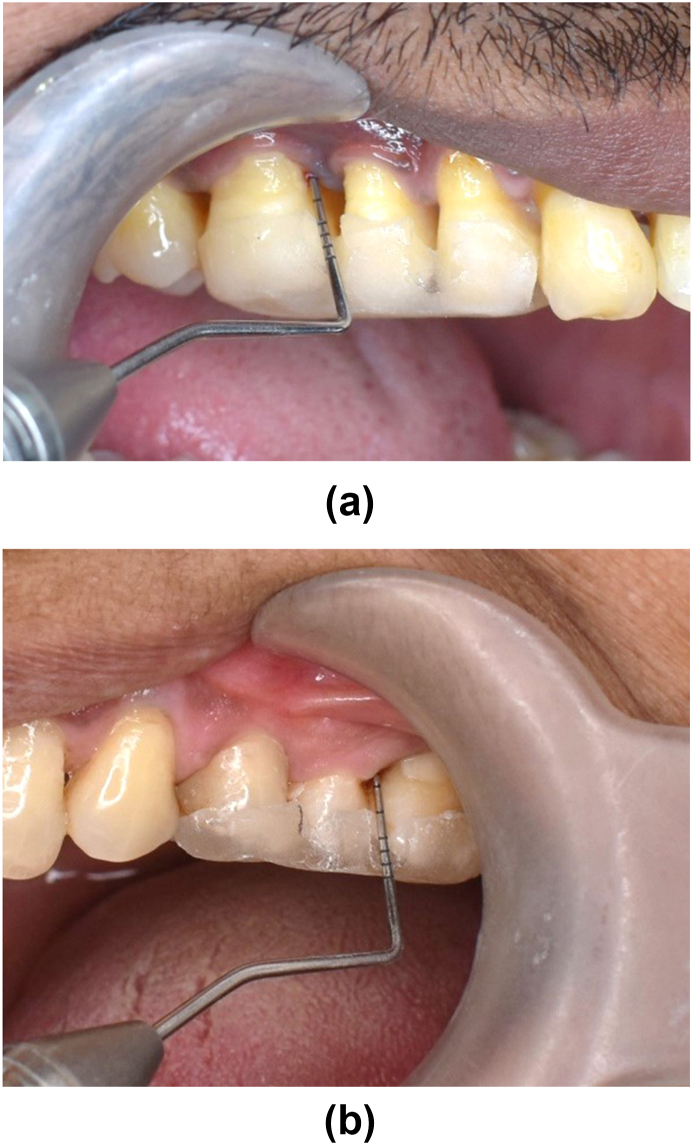

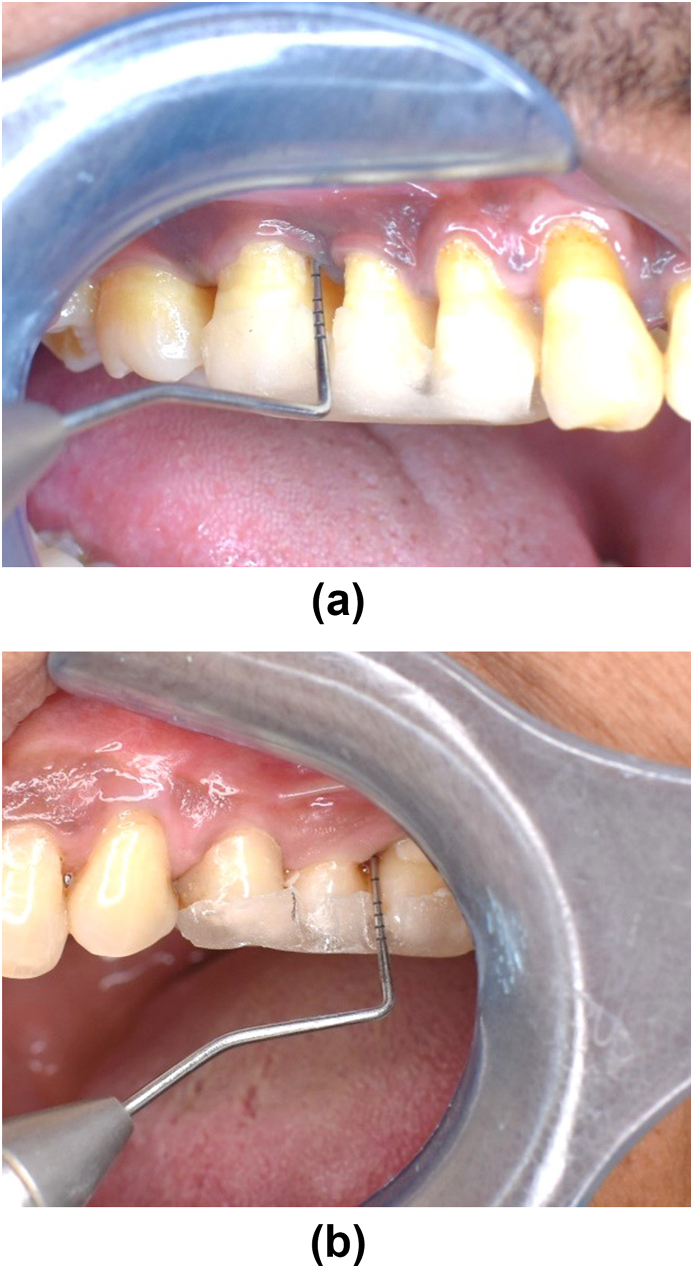

Study subject taken from the dental OPD of both centres were selected as per inclusion and exclusion criteria. Randomization of the patient into groups were carried out in a parallel, examiner-masked design using Block randomization method. Patients were given detailed verbal and written description of the study. All patients signed an informed consent form prior to commencement of the treatment. Within 60 patients, 2 groups were made for study. After recording baseline clinical parameters [Fig. 2a and b] and saliva collection for immunological parameters, SRP of whole mouth with ultrasonic scalers were performed for both group. Test group were given 500 mg of Omega-3 PUFA capsules twice daily for three months (flax seed 250 mg, black seed 150 mg and sea buckthorn 100 mg extract). Oral hygiene instructions were given to all patients. No antibiotics or antiplaque or anti-inflammatory agents were prescribed after treatment. After 3 months, the clinical parameters re-evaluated [Fig. 3a and b] The saliva samples were collected and sent for biochemical analysis to estimate the levels of IL-1β using ELISA Kits. After 6 months, all parameters were reassessed [Fig. 4a and b].

Fig. 2.

(a) Test Group – at baseline PD 6mm. (b) Control Group – at baseline PD 6mm.

Fig. 3.

(a) Test Group – at 3 months PD 3mm. (b) Control Group – at 3 months PD 3mm.

Fig. 4.

(a) Test Group – at 6 months PD 4mm. (b) Control Group – at 6 months PD 4mm.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated to test the null hypothesis with 5% level of significance and 90% power. Differences between the two populations were considered significant when p < 0.05. Statistical method used for inter-group and intra-group using unpaired t test and paired t test (SPSS software ver 26.0) were carried out.

Result

A total of 60 patients out of which 37 male and 23 female subjects were registered for the study, in the age group of 18–65 years. There was an equal distribution of patients both above and below 40 years age, suggestive of incidence of periodontitis can be seen both young and older age groups. In present study there was more inclusion of male gender patients, however it was mere based on the inclusion exclusion criteria and it was not of any statistical significance. Test subjects tolerated the supplementation of omega-3 PUFA very well without any complications like adverse or allergic reaction.

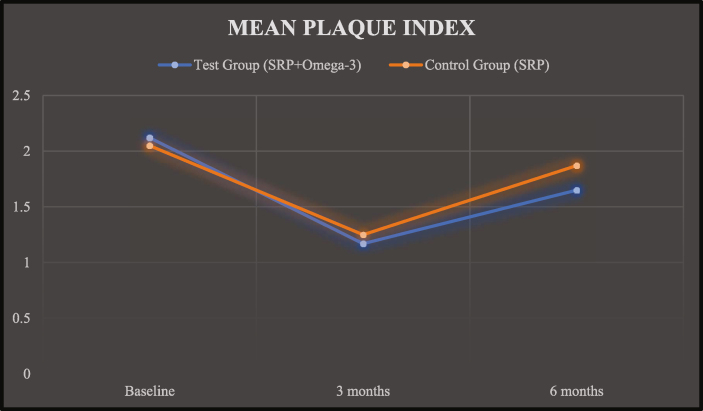

The PI scores of test group and control group at baseline was 2.12 ± 0.47 and 2.05 ± 0.29, at 03 months was 1.17 ± 0.35 and 1.25 ± 0.34 and at 06 months was 1.65 ± 0.42 and 1.87 ± 0.55, respectively (Graph 1).

Graph 1.

Mean plaque index.

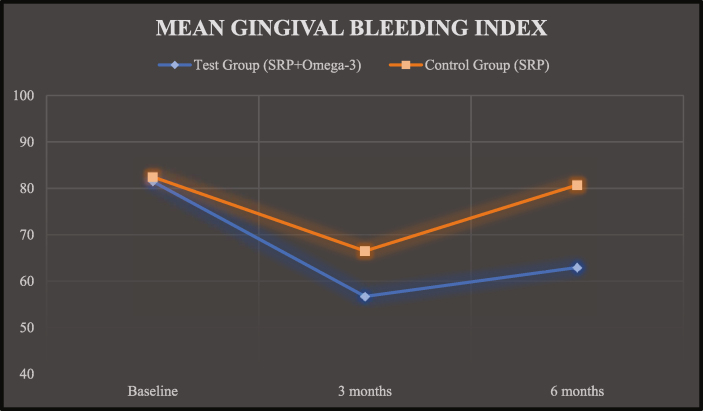

The GBI scores of test group and control group at baseline was 81.49 ± 8.21 and 82.47 ± 7.62, at 03 months was 56.70 ± 11.74 and 66.49 ± 7.71 and at 06 months was 62.95 ± 17.30 and 80.71 ± 7.99, respectively (Graph 2).

Graph 2.

Mean gingival bleeding index (GBI).

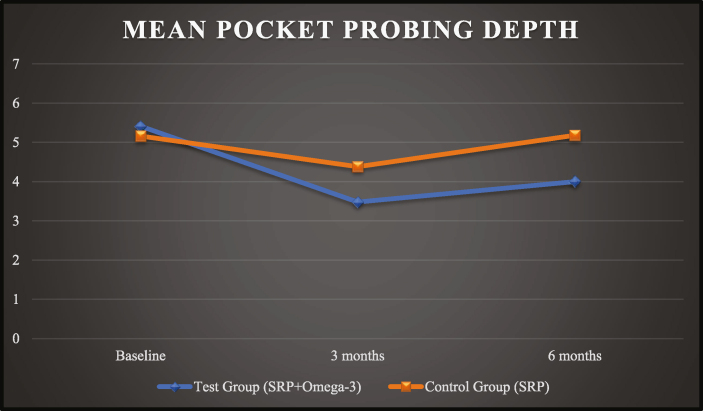

The PPD scores of test group and control group at baseline was 5.41 ± 1.07 and 5.16 ± 1.08, at 03 months was 3.48 ± 0.34 and 4.38 ± 1.01 and at 06 months was 4.00 ± 0.41 and 5.18 ± 1.12, respectively (Graph 3).

Graph 3.

Mean pocket probing depth (PPD).

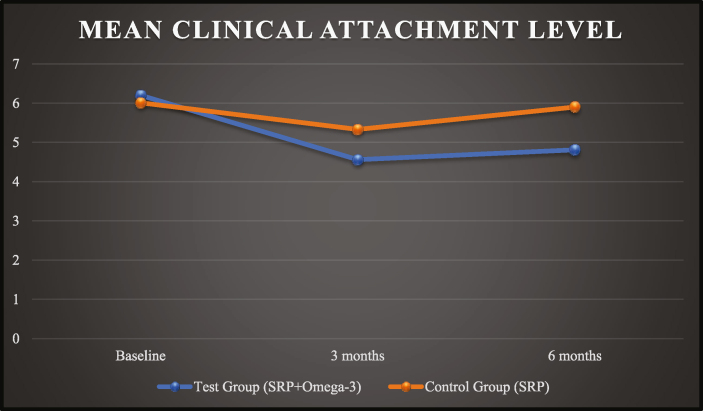

The CAL scores of test group and control group at baseline was 6.20 ± 1.17 and 6.01 ± 1.28, at 03 months was 4.56 ± 0.53 and 5.33 ± 1.02 and at 06 months was 4.81 ± 0.63 and 5.90 ± 1.35, respectively (Graph 4).

Graph 4.

Mean clinical attachment level (CAL).

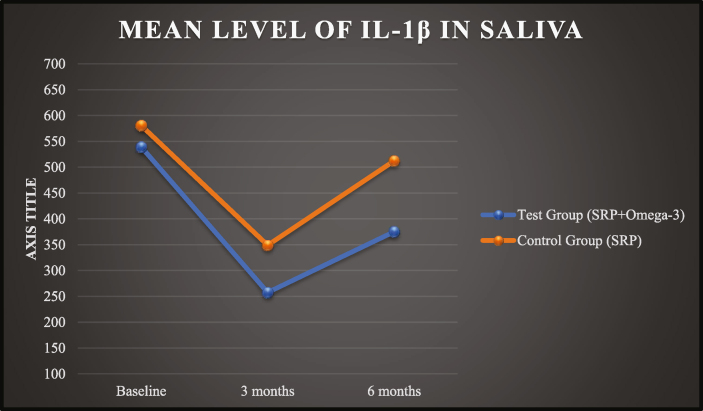

At baseline, the mean level of IL-1β in saliva in test group was 539.24 ± 151.14 pg/μl and in control group was 580.78 ± 147.15 pg/μl. There was no significant difference of IL-1β levels at baseline. Following supplementation of omega-3 PUFA capsule in Test Group, the mean levels of IL-1β was decreased to 257.64 ± 106.86 pg/μl following 90 days after therapy. The Control group also showed a reduction in the mean levels of IL-1β to 349.04 ± 116.94 pg/μl at 90 days. After 180 days post therapy, there is again rise in mean values of IL-1β in both the groups as 375.26 ± 136.16 pg/μl in test group and 512.44 ± 166.24 pg/μl in control group (Graph 5).

Graph 5.

Mean IL-1β levels in saliva.

Discussion

Periodontal disease is a multi-factorial disease caused by microbial flora which is present in the subgingival plaque along with host tissue response leading to the destruction of the supporting structures of the teeth. The cumulative effects of the toxins produced by bacteria and release of various pro-inflammatory chemical mediators like IL, MMPs and PG results in overall destruction of the attachment apparatus around teeth and this is responsible for the chronicity of the periodontal disease.1,2

Traditional treatment modality in periodontal disease is to reduce or eliminate these pathogens. Conventional nonsurgical periodontal therapy is mechanical debridement of the root surfaces in order to reduce the microbial load but this cannot completely eradicate these periodontal pathogens. SRP alone may not achieve a complete removal of microbial population especially in deep inaccessible area to periodontal instruments.3 This results in the immune response activation and clinical signs of periodontal tissue inflammation. Bacterial burden elicits an increase in lipopolysaccharide, resulting in an increase in pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-ɑ.10 This inflammation, in turn, provokes osteoclastogenesis modifying the levels of receptor activator on nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL) and/or osteoprotegerin (OPG).11

Nowadays, HMT seems to be an adequate concept for the treatment of periodontal diseases. The main aim of this therapy was to minimise tissue destruction, to enhance rapid resolution of inflammation and promote regeneration of the periodontal tissues by modifying or downregulating the destructive aspects of the host response as well as by upregulating the protective or regenerative responses.12 The concept of treatment was to enrich standard periodontal therapies (non-surgical or surgical approach) with HMT delivered systemically or locally. As a result, wound healing and periodontal stability without impairing normal defence mechanisms or inducing inflammation can be achieved.

Recently, increase in use of omega-3 PUFA as an adjunctive therapy to conventional SRP has been documented.13, 14, 15, 16 Omega-3 PUFA, including DHA and EPA, have been proven to have a wide range of effects, including anti-inflammatory, immunoregulatory and antioxidant-enhancing properties.17,18 Omega-3 PUFA have therapeutic and protective qualities in managing of various inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, asthma, atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease and periodontitis.19

Mechanism of action of omega-3 fatty acids is attributed as EPA and DHA competes with arachidonic acid at two levels. First it gets integrate into cell membrane phospholipid, reducing the levels of AA-derived eicosanoid. Second by competing as substrate for COX and LOX pathway, leading to production of EPA and DHA derived eicosanoid which includes resolvins, protectins and maresins.20

The present randomized control trial study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of omega-3 PUFA when used as an adjunct with SRP in management of patients with chronic periodontitis. To best of our information this is the first study where plant-based omega-3 PUFA capsules have been studied to evaluate its action on reduction of clinical and immunological parameters i.e., IL-1β levels along with other clinical parameters in patients with chronic periodontitis.

The present study was a multicentric study which was conducted in tertiary care government hospital in two different parts of India. The study was conducted in total 60 patients over a duration of 6 months where clinical and immunological assessment were carried at baseline, three months and six months. The clinical parameters included PI, GBI, PPD and CAL. The immunological parameter was IL-1β in saliva.

There was no intergroup significant difference seen in reduction in plaque index values from baseline to three months (p = 0.471) and from 3 months to 6 months (p = 0.436). However, the intragroup results showed statistically significant difference in both groups at 3 months and 6 months. This can be attributed to the fact that there was a reduction in supragingival plaque after SRP and oral hygiene instructions received during the preliminary visit as well enough motivation in patients for good maintenance of oral hygiene.

In terms of GBI there was significant reduction in values after 90 days (p = <0.001) and 180 days (p = <0.001) in test group suggestive of long term anti-inflammatory action of omega-3. Similar observations were quoted by Stando et al (2020)27 and Deore et al (2014).22

With regard to PPD and CAL, there was a significant reduction from baseline to 90 days and 180 days in test group. However, the values at 180 days were greater than 90 days, but they were statistically significant when compared to control group. The results were in accordance with the studies conducted by Elgendy et al. (2018), Chatterjee et al. (2022), Deore et al. (2014), El Sharkawy et al. (2010), Elkhouli (2011) and Kujur et al. (2020).20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 However, study done by Salman et al (2014) showed a significant difference in PPD but not CAL,26 whereas study by Stando et al (2020) in their RCT showed significant difference in CAL but not PPD.27

In this study, at baseline the parameters were comparable among test and control groups [Table 1]. After 3 months of supplementation of omega-3 PUFA, test group showed marked decrease in levels of IL-1β from baseline and found to be statistically significant with a p value of 0.003 [Table 2]. Also, after 180 days, the levels of IL-1β in test group were statistically significant (p = 0.001), which shows long term effect of omega-3 on inflammatory cytokines as compared to control group [Table 3]. These results were in accordance with the studies done by Naqvi et al (2014), Elkhouli et al (2011), Umrania et al (2017) and Elwakeel et al (2015).16,24,28,29 However, a RCT done by Stando et al (2020) did not show any statistical difference in salivary levels of IL-1β between both groups.27

Table 1.

Comparison of test and control at baseline.

| Test | Control | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PI | 2.12 ± 0.47 | 2.05 ± 0.29 | 0.471 |

| GBI | 81.49 ± 8.21 | 82.47 ± 7.62 | 0.635 |

| PPD(mm) | 5.41 ± 1.07 | 5.16 ± 1.08 | 0.363 |

| CAL(mm) | 6.20 ± 1.17 | 6.01 ± 1.28 | 0.552 |

| IL-1B (pg/μl) | 539.24 ± 151.14 | 580.78 ± 147.15 | 0.285 |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. PI: Plaque index, GBI: Gingival bleeding index, PPD: Pocket probing depth, CAL: Clinical attachment level, IL-1B: Interleukin-1 beta.

Table 2.

Comparison of test and control post 90 days.

| Test | Control | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PI | 1.17 ± 0.35 | 1.25 ± 0.34 | 0.436 |

| GBI | 56.70 ± 11.74 | 66.49 ± 7.71 | 0.001∗ |

| PPD(mm) | 3.48 ± 0.34 | 4.38 ± 1.01 | 0.001∗ |

| CAL(mm) | 4.56 ± 0.53 | 5.33 ± 1.02 | 0.001∗ |

| IL-1B (pg/μl) | 257.64 ± 106.86 | 349.04 ± 116.94 | 0.003∗ |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. PI: Plaque index, GBI: Gingival bleeding index, PPD: Pocket probing depth, CAL: Clinical attachment level, IL-1B: Interleukin-1 beta.

Table 3.

Comparison of test and control post 180 days.

| Test | Control | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PI | 1.65 ± 0.42 | 1.87 ± 0.55 | 0.084 |

| GBI | 62.95 ± 17.30 | 80.71 ± 7.99 | 0.001∗ |

| PPD(mm) | 4.00 ± 0.41 | 5.18 ± 1.12 | 0.001∗ |

| CAL(mm) | 4.81 ± 0.63 | 5.90 ± 1.35 | 0.001∗ |

| IL-1B (pg/μl) | 375.26 ± 136.16 | 512.44 ± 166.24 | 0.001∗ |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. PI: plaque index, GBI: Gingival bleeding index, PPD: Pocket probing depth, CAL: Clinical attachment level, IL-1B: Interleukin-1 beta.

Varying doses of omega-3 PUFA supplementation have been used in other clinical trials, among which Martinez et al (2014) have used 3 capsules of 300 mg each per day for 12 months. Each capsule contained EPA 180 mg and DHA 120 mg. Deore et al (2014) had used one capsule/day with the same composition, being 300 mg of omega-3 PUFA with EPA 180 mg and DHA 120 mg for 3 months.15 Elkhouli et al (2011) used three capsules of 1 g of omega-3 PUFAs containing 300 mg of DHA and 150 mg of EPA with 75 mg of aspirin for 6 months.24 The American Heart Association has suggested that a dose of 0.5–1.8 g/day of EPA + DHA is generally regarded as safe in healthy people.30 Hence, dosage of 500 mg twice a day was taken in this study which was well within the range of safety dose.

With limited sample size the present study shown statistically superior results in clinical and immunological parameters after dietary supplement of omega-3 PUFA as an adjunct to SRP in patients with chronic periodontitis.

Conclusion

This multicentric randomized control trial involved a comparative evaluation of efficacy of dietary supplementation of omega-3 PUFA as an adjunct to SRP in patients with chronic periodontitis. The present study concluded that, omega-3 PUFA can be recommended as an adjunct to SRP in treatment of chronic periodontitis and serves as an anti-inflammatory agent. Though, the study has positive outcome in proving the efficacy of omega-3 in treatment of periodontitis as an adjunctive modality to SRP but it needs further more studies with longer duration and larger sample size to conclude the same. The limitation of the present study was selection of limited inflammatory parameters, hence it is proposed to carry out future studies with multiple inflammatory markers with long-term follow-up.

Disclosure of competing interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on Armed Forces Medical Research Committee Project No. 5431/2021 granted and funded by the office of the Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services and Defence Research Development Organization, Government of India.

References

- 1.Offenbacher S. Periodontal diseases: pathogenesis. Ann Periodontol. 1996 Nov;1(1):821–878. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silva N., Abusleme L., Bravo D., et al. Host response mechanisms in periodontal diseases. J Appl Oral Sci. 2015 Jun;23(3):329–355. doi: 10.1590/1678-775720140259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cobb C.M. Non-surgical pocket therapy: mechanical. Ann Periodontol. 1996 Nov;1(1):443–490. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bui F.Q., Almeida-de-Silva C.L., Huynh B., et al. Association between periodontal pathogens and systemic disease. Biomed J. 2019;42:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaye E.K. n-3 fatty acid intake and periodontal disease. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;27 doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.08.017. Published October. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salvi G.E., Lang N.P. Host response modulation in the management of periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(suppl 6):108–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deore G.D., Gurav A.N., Patil R., Shete A.R., Naiktari R.S., Inamdar S.P. Omega 3 fatty acids as a host modulator in chronic periodontitis patients: a randomised, double blind, palcebo- controlled, clinical trial. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2014;44(1):25–32. doi: 10.5051/jpis.2014.44.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figueredo C.M., Martinez G.L., Koury J.C., Fischer R.G., Gustafsson A. Serum levels of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2013;84:675–682. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.120171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page R.C. The role of inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J Periodont Res. 1991;26:230–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1991.tb01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reis C., Da Costa A.V., Guimarães J.T., et al. Clinical improvement following therapy for periodontitis: Association with a decrease in IL-1 and IL-6. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8:323–327. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arron J.R., Choi Y. Bone versus immune system. Nature. 2000;408:535–536. doi: 10.1038/35046196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatavadekar N.B., Williams R.C. New directions in host modulation for the management of periodontal disease: commentary. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:124–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bendyk A., Marino V., Zilm P.S., Howe P., Bartold P.M. Effect of dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on experimental periodontitis in the mouse. J Periodontal Res. 2009 Apr;44(2):211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2008.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keskiner I., Saygun I., Bal V., Serdar M., Kantarci A. Dietary supplementation with low-dose omega-3 fatty acids reduces salivary tumor necrosis factor-a levels in patients with chronic periodontitis: a randomized controlled clinical study. J Periodont Res. 2017;52:695–703. doi: 10.1111/jre.12434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azuma M.M., Gomes-Filho J.E., Cardoso C.D., et al. Omega 3 fatty acids reduce the triglyceride levels in rats with apical periodontitis. Braz Dent J. 2018 Mar;29:173–178. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201801702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naqvi A.Z., Hasturk H., Mu L., et al. Docosahexaenoic acid and periodontitis in adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Dent Res. 2014;93:767–773. doi: 10.1177/0022034514541125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wall R., Ross R.P., Fitzgerald G.F., Stanton C. Fatty acids from fish: the anti-inflammatory potential of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids. Nutr Rev. 2010;68:280–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bagga D., Wang L., Farias-Eisner R., Glaspy J.A., Reddy S.T. Differential effects of prostaglandin derived from ω-6 and ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on COX-2 expression and IL-6 secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1751–1756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0334211100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Ravensteijn M.M., Timmerman M.F., Brouwer E.A., Slot D.E. The effect of omega-3 fatty acids on active periodontal therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2022 Oct;49(10):1024–1037. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elgendy E.A., Kazem H.H. Effect of omega-3 fatty acids on chronic periodontitis patients in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled clinical study. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2018;4:327–332. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a40957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chatterjee D., Chatterjee A., Kalra D., Kapoor A., Vijay S., Jain S. Role of adjunct use of omega 3 fatty acids in periodontal therapy of periodontitis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Biol Cranio Res. 2022 Jan 1;12(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2021.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deore G.D., Gurav A.N., Patil R., Shete A.R., NaikTari R.S., Inamdar S.P. Omega 3 fatty acids as a host modulator in chronic periodontitis patients: a randomised, double-blind, palcebo-controlled, clinical trial. J Perio Implant Sci. 2014 Feb 1;44(1):25–32. doi: 10.5051/jpis.2014.44.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Sharkawy H., Aboelsaad N., Eliwa M., et al. Adjunctive treatment of chronic periodontitis with daily dietary supplementation with omega-3 Fatty acids and low-dose aspirin. J Periodontol. 2010 Nov;81(11):1635–1643. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elkhouli A.M. The efficacy of host response modulation therapy (omega-3 plus low-dose aspirin) as an adjunctive treatment of chronic periodontitis (clinical and biochemical study) J Periodontal Res. 2011;46:261–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2010.01336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kujur S.K., Goswami V., Nikunj A.M., Singh G., Bandhe S., Ghritlahre H. Efficacy of omega 3 fatty acid as an adjunct in the management of chronic periodontitis: a randomized controlled trial. Indian J Dent Res. 2020;31:229–235. doi: 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_647_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salman S.A., Akram H.M., Ali O.H. Omega-3 as an adjunctive to non surgical treatment of chronic periodontitis patients. ISOR J Dental Med Sci. 2014;13:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stańdo M., Piatek P., Namiecinska M., Lewkowicz P., Lewkowicz N. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids EPA and DHA as an adjunct to non-surgical treatment of periodontitis: a randomized clinical trial. Nutrients. 2020 Aug 27;12(9):2614. doi: 10.3390/nu12092614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Umrania V.V., Rao Deepika P.C., Kulkarni M. Evaluation of dietary supplementation of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids as an adjunct to scaling and root planing on salivary interleukin-1 β levels in patients with chronic periodontitis: a clinico-immunological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2017;21:386–390. doi: 10.4103/jisp.jisp_16_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elwakeel N.M., Hazaa H.H. Effect of omega 3 fatty acids plus low-dose aspirin on both clinical and biochemical profile of patients with chronic periodontitis and type 2 diabetes: a randomized double blind placebo-controlled study. J Periodontal Res. 2015;50:721–729. doi: 10.1111/jre.12257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kris-Etherton P.M., Harris W.S., Appel L.J., Committee AHA Nutrition, American Heart Association Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: new recommendations from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:151–152. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000057393.97337.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]