Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is still epidemic around the world. The manipulation of SARS-CoV-2 is restricted to biosafety level 3 laboratories (BSL-3). In this study, we developed a SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT replicon delivery particles (RDPs) encoding a dual reporter gene, GFP-HiBiT, capable of producing both GFP signal and luciferase activities. Through optimal selection of the reporter gene, GFP-HiBiT demonstrated superior stability and convenience for antiviral evaluation. Additionally, we established a RDP infection mouse model by delivering the N gene into K18-hACE2 KI mouse through lentivirus. This mouse model supports RDP replication and can be utilized for in vivo antiviral evaluations. In summary, the RDP system serves as a valuable tool for efficient antiviral screening and studying the gene function of SARS-CoV-2. Importantly, this system can be manipulated in BSL-2 laboratories, decreasing the threshold of experimental requirements.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, RDP, Antiviral evaluation, Mouse model, BSL-2

Highlights

-

•

A SARS-CoV-2 replicon delivery particle system harboring antiviral evaluation is developed and optimized.

-

•

A mouse model for the SARS-CoV-2 replicon delivery particle is established.

-

•

Antivirals are evaluated in vivo and in vitro at BSL-2.

1. Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 emerged at the end of 2019, and caused coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic around the world. Over the past two decades, two other human coronavirus, SARS-CoV in 2002 and MERS-CoV in 2012, have also caused severe acute respiratory syndrome Hu et al. (2021). Additionally, four other human coronaviruses (229E, OC43, NL63 and HKU-1) have caused only mild symptoms (Tang et al., 2022). SARS-CoV-2 is a member of the Coronaviridae family included in the Nidovirales. The SARS-CoV-2 has a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome of ∼30 Kb. The 5′ two-thirds of the genome compromise two open read frames, ORF1a and ORF1ab, which encode 16 non-structural proteins (nsp1–10 and nsp12–16) through a ribosomal frameshifting mechanism (Chen et al., 2020). The 3′ one-third of genome encodes four structural proteins (spike, envelope, membrane and nucleocapsid proteins) and seven accessory proteins (ORF3a, 6, 7a, 7b, 8 and 10) (Wu et al., 2020). The N protein is located inside the SARS-CoV-2 virion and binds to the viral genomic RNA, encapsulating it into viral particles. The N protein plays a vital role in the virus's life cycle, contributing significantly to its replication and assembly (Bai et al., 2021).

With the persistence of the pandemic, numerous SARS-CoV-2 variants have emerged, rendering some antiviral drugs and neutralizing antibodies ineffective against these variants (Takashita et al., 2022; Thorne et al., 2022). It is urgent for antiviral evaluation and screening. However, due to the high pathogenicity and infectivity of SARS-CoV-2, research involving the virus is still confined to BSL-3 laboratories, which are not cost-effective and require well-trained technicians. To overcome these limitations, the replicon system has proven to be advantageous. Replicon is a non-infectious, self-replicative RNA that lacks the viral structural genes but retains the necessary genes for replication (Wang et al., 2022). Additionally, several trans-complementation systems have been established, wherein the viral genome lacks the certain viral structural genes, and the missing structural protein is trans-complemented in the cells (Ju et al., 2021; Ricardo-Lax et al., 2021; Zhang X. et al., 2021; Cheung et al., 2022; Malicoat et al., 2022). The resulting virions can replicate strictly in trans-complement cells, while they are unable replicate or assembly in the wild-type cells (which do not express the corresponding viral structural protein). This system can be manipulated in BSL-2 laboratories.

Animal models play a crucial role in studying viral pathogenesis, screening antiviral drugs, and developing vaccines. Several transgenic mice expressing human angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (hACE2) have been developed for this purpose (Bao et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2020; Winkler et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2021). Additionally, mouse models transduced with hACE2 via adenoviral viral vector have been used for SARS-CoV-2 infection (Hassan et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2021). However, it is important to note that SARS-CoV-2 is restricted to BSL-3 facilities, and the availability of mouse model that can support the infection of SARS-CoV-2 RDP/trVLP is limited (Yang et al., 2023). Therefore, there is a requirement to develop a mouse model specifically for RDP infection.

Here, we developed a dual reporter RDP utilizing GFP-HiBiT reporters. The incorporation of visible and easily detected reporter genes provides enhanced accuracy in antiviral evaluations. Alongside conventional methods such as RT-qPCR, the fluorescence signal and luciferase activity of RDP serve as reliable indicators of viral load and replication. Our RDP system has demonstrated considerable stability as the reporter gene remained intact throughout five passages, and the constructed cell line consistently expressed N protein at a high level. Moreover, we successfully delivered the SARS-CoV-2 N protein to the K18-hACE2 KI mice through lentivirus-N transduction. This mouse model supported the replication of the RDP and resulted in pathological changes in the lungs post-infection.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

HEK293T was cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S, Gibco). Caco-2 was cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% P/S. Caco-2-N was cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% P/S and 2 μg/mL puromycin at 37 °C with 5% CO2. All cells were tested negative for mycoplasma.

2.2. Plasmids construction

The seven cDNA fragments of SARS-CoV-2 were synthesized by the GenScript Company and cloned into plasmid pUC57. Fragment G was modified by replacing the N gene by the reporter gene (GFP, Nluc-GFP or GFP-HiBiT) using overlap PCR. Fragment F-BA.5-S was synthesized by the Tsingke Biotechnology Company.

To construct the lentiviral expression vector pLVX-mCherry-N-puro, the SARS-CoV-2 N gene was amplified from plasmid pUC57-SARS-CoV-2-N. The mCherry-F2A fragment was amplified from a mCherry ZIKV virus cDNA plasmid. The PCR products were introduced into pLVX-T2A-puro vector using HieffClone Plus Multi One Step Cloning kit.

For TAR clone, we first constructed a E. coli-yeast shuttle plasmid based on pCC1-BAC plasmid (Clonetech) by inserting a CEN-Trp fragment. This modified vector was designated as pCC1-Trp. We amplified the SARS-CoV-2 A, B, C, D, E, F and G fragments with specific primers containing 59 bp overlaps as indicated in Supplementary Table S1. The vector pCC1-Trp was amplified by PCR using primers with 59 bp overlaps to fragments encompassing the 5′ or 3′ ends of A and G fragments, respectively. All amplifications were performed using Phanta Flash DNA polymerase (Vazyme). We then transformed the vector and seven fragments into yeast using LiCl/PEG method and allowed the yeast grown on SD-Trp plate at 30 °C for 2–3 days. We picked 6–8 colonies randomly and extracted the yeast plasmids using yeast plasmid extraction kit. The extracted plasmid was used as template for screening by multiplex PCR. Six primers pairs annealing to the junction of assembly fragments were used to validate the assembly products. The positive plasmid was subsequently transformed into EPI300 or DH10β electrocompetent cells for further amplification and subjected to Sanger sequencing.

2.3. Lentivirus packaging and selection of Caco-2-N cell line

The plasmid pLV-mCherry-N, pMD2.G and psPAX2 was transfected into HEK293T cell using Neofect DNA transfection reagent (Neofect). The supernatants were harvested at 48 h and 72 h post-transfection, pooled and filtered through a 0.45 μm filter. Caco-2 cells were transduced with 2 mL lentivirus supernatants supplemented with 10 μg/mL polybrene for 24 h. After 24 h post-transduction, the cells were split into a 15 cm dish and cultured in the DMEM medium supplemented with 2 μg/mL puromycin. After 2 weeks, we picked the puromycin-resistant cell colonies into 48-well plate for further culture.

2.4. In vitro transcription of RNA and recovery of RDP

About 10 μg pCC1-Trp-SARS-CoV-2 plasmid containing RDP genome cDNA was linearized by endonuclease NotI and subjected to phenol–chloroform extraction. The full-length RNA transcript was synthesized using the T7 mMessage mMachine kit (Thermo Fisher). To generate the SARS-CoV-2 N RNA transcript, the template was amplified from plasmid pUC57-SARS-CoV-2-F with the primers T7-N F and N-polyA R (as indicated in Supplementary Table S1). The purified PCR product was then used for in vitro transcription using T7 mMessage mMachine kit (Thermo Fisher). The transcripts were precipitated in LiCl and resuspended in nuclease-free water. Twenty micrograms of full-length RNA transcript and 20 μg N RNA transcript were electroporated into 8 × 106 Caco-2-N cells using GenePluser apparatus (Bio-rad) with setting of 270 V, 950 μF. The electroporated cells were then seeded in a 10 cm dish and the reporter gene signal was monitored daily. Two days post electroporation, 1 mL P0 virus was collected and inoculated into a 12-well plate containing 80–90% confluent Caco-2-N cells. The P1 virions were collected and stored at −80 °C. The TCID50 of virions was calculated using Reed & Muench method.

2.5. RNA isolation and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Thermo) following the manufacturer's instructions. 100 μL culture supernatant was mixed with three volumes of Trizol LS reagent and extracted according to the manufacturer's instructions. The final RNA was dissolved in 20 μL RNase-free water. RNA (2 μL) was used for reverse transcription of first cDNA in 20 μL reaction by using PrimeScript RT Reagent kit (Takara). cDNA (2 μL) was used as template for quantitative PCR with HieffUnicon® TaqMan multiplex qPCR master mix. The primers and probe targeting SARS-CoV-2 E gene used for quantitative reverse transcription were mentioned as described previously (Liu et al., 2023). A standard curve was generated by determining copy numbers from serially dilutions.

2.6. Antibody and antiviral drug testing

Caco-2-N cells were plated into a white opaque 96-well plate with a density of 1 × 104 cells per well. For antiviral drugs, the culture medium was replaced by medium containing different dose of the indicated antiviral drugs 16 h after seeding. After an additional 8 h, the cells were washed twice by PBS and then infected by RDP at MOI of 0.05 for 1 h. Then, the cells were washed twice with PBS and cultured with fresh drug-containing medium. For neutralizing antibody, the neutralizing antibody was incubated with RDP for 1 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2 prior to infection. At 48 h post-infection, the cells were lysed and luciferase signal was measured with Nano-Glo HiBiT Lytic Detection System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For flow cytometer analysis, the cells were harvested and suspended in PBS. Approximately 104 cells form each sample were proceeded for detection in the flow cytometer.

The relative signal rate was calculated by normalizing the signals of compound-treated groups to the non-treated groups (set as 100%). The concentrations that inhibiting 50% of luciferase signal were calculated using a nonlinear regression model (four parameters). Experiments were performed in triplicates.

2.7. Cytotoxicity assay

Caco-2-N cells were seeded into a 96-well plate with a density of 1 × 104 cells per well. After 16 h, 100 μL of the indicated concentrations of compounds were added. At 24 h post-treatment, 10 μL of CCK-8 Cell Counting Kit (Vazyme) was added into each well. After incubate at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 1 h, absorbance of 450 nm was measured using Multi-function microplate reader (Molecular Devices). The relative cell viability was calculated by normalizing absorbance of the compound-treated groups to that of the DMSO-treated groups (set as 100%).

2.8. Mice infection

Heterozygous B6/JGpt-H11em1Cin(K18-ACE2)/Gpt mice (K18-hACE2 KI mice, #T037657) were obtained from GemPharmatech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China) and housed in specific pathogen free (SPF) environment. The 8–12-week-old mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and divided into several groups. For authentic SARS-CoV-2-infected group, the K18-hACE2 KI mice were intranasally infected with 250 PFU SARS-CoV-2 at dpi 0. The lentivirus-infected group were intranasally infected with 2 × 109 copies lentivirus-SARS-CoV-2-N (in 50 μL DMEM). The lentivirus plus SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP group were intranasally infected with 4 × 106 TCID50 SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP 14 days post lentivirus-N infection. The mock control group were inoculated with equal volume DMEM. In the remdesivir (RDV) group, the mice were subcutaneous treated with 25 mg/kg RDV at dpi 1, and this regimen was continued until 5 dpi. The REGN10933 group mice were injected with 10 mg/kg antibodies at −1 dpi. The mice were observed and weighted daily post infection of SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP. Mice were sacrificed at 7 dpi and the tissues were collected. Lung samples were subjected to H&E and immunofluorescence staining.

2.9. Histopathology analyses

Lung samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for at least 48 hours, embedded in paraffin, and cut into sections. The fixed tissue samples were used for H&E staining and indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFAs). Antibody used for IFAs are as follows: anti-hACE2 antibody and anti-SARS-CoV-2 N antibody (SinoBiological). The image information was collected using a Pannoramic MIDI system (3DHISTECH).

2.10. Western blotting

The lung of lentivirus-SARS-CoV-2-N infected mice was homogenate in the refiner and then lysed with RIPA containing protease inhibitor cocktail. The homogenate lysate was separated using 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The transferred membrane was blocked with 10% skimmed milk in PBST (PBS containing 0.1% Tween) and then incubated with mouse anti-SARS-CoV-2-N antibody (Sino Biological). HRP-conjugated goat-anti-mouse IgG Fc was used as secondary antibody. The blots were visualized by a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

2.11. Statistical analysis

All date represent the results of three independent experiments and are shown as the mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was carried out using Graphpad Prism 8 for Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA. Statistically significant differences are noted as follows: ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

3. Results

3.1. The construction of a SARS-CoV-2 reporter RDP system

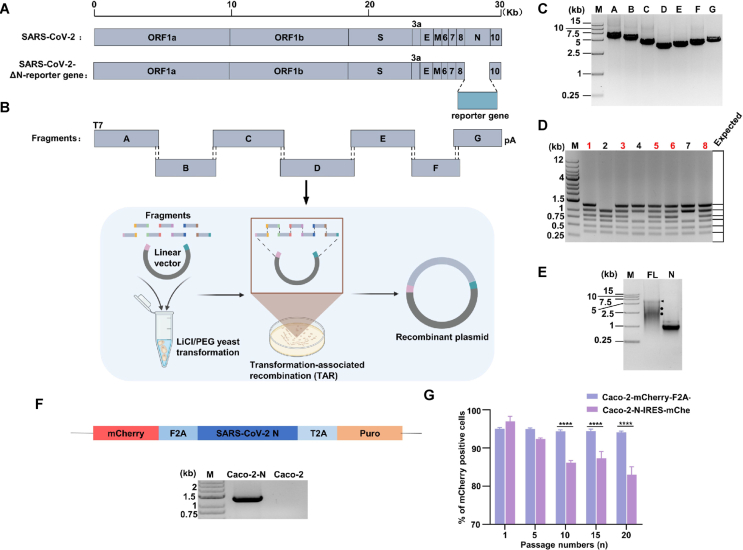

We generated a full-length complementary DNA of SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-Hu-1 strain (NC_045512) by synthesizing seven contiguous cDNA fragments covering the entire genome (Genescript). These synthesized cDNA fragments were cloned into pUC57 vector plasmid. A T7 promoter was added to the 5′ terminal of fragment A and fragment G was modified by replacing the N gene with reporter genes (GFP, Nluc-GFP and GFP-HiBiT). The details of the seven fragments and the scheme of yeast transformation-associated clone are depicted in Fig. 1A, B. For construction of additional spike gene (S) D614G and BA.5 mutant RDPs, the F fragment was replaced with the corresponding F fragments harboring S D614G (fragment F-D614G) and S BA.5.2 (fragment F-BA.5.2) mutations, respectively. To prepare the overlapping fragments for TAR cloning, seven fragments and pCC1-Trp vector were amplified with specific primers pairs (Supplementary Table S1) using High-fidelity DNA polymerase. The PCR products of seven fragments and vector (Fig. 1C) were gel-purified and transformed (∼200 ng each) into MaV203 yeast strain. Multiplex PCR were performed to screen the colonies harboring the entire RDP genome, and the results showed that TAR clone method is of high efficiency (Fig. 1D). The NotI-linearized legitimate plasmid was used as a template for in vitro transcription (IVT) of the full-length mRNA. The IVT product was analyzed on the agarose gel (Fig. 1E), and the highest molecular band stand for the full-length RNA (indicated by the black arrow) with some abortive transcript (indicated the circles).

Fig. 1.

Design and construction of SARS-CoV-2 ΔN reporter RDP. A Schematic of SARS-CoV-2 genome, the open reading frames (ORFs), structural proteins (S, E, M, N) and accessory proteins (3a, 6, 7, 8, 10) are indicated. B Schematic of SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-reporter RDP genome and fragments for yeast assembly (bottom panel). The reporter gene was placed downstream of the regulatory of N to replace the N sequence. C Electrophoresis of the seven DNA fragments. Seven purified DNA fragments (about 500 ng) were run on a 1% agarose gel. The DL15000 DNA marker is indicated. D Multiplex PCR screening and identification of yeast clones carrying SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-reporter RDP genome. Six sets of primers were used to ensure the presence of all junctions between the adjacent fragments. The expected junction PCR product sizes are indicated in the right panel. The 1 kb DNA ladder is indicated. E Gel analysis of full-length (FL) and N RNA transcripts. About 500 ng in vitro transcribed RNAs were analyzed on a 0.8% native agarose gel. The DL15000 marker is indicated. Arrow indicates the genome full-length RNA transcripts. Circles denotes the truncated RNA transcripts. F Construction of a lentivirus transfer plasmid encoding mCherry and N protein, and RT-PCR analyses were performed on Caco-2-N cells and Caco-2 cells to detect the N gene. G The mCherry expression in serially passaged Caco-2-N cells for 20 passages. The percentage of P1, P5, P10, P15 and P20 mCherry positive cells are presented. The results are presented as means ± SD from three replicates. About 104 cells were counted for each replicate. Statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Due to the absence of the N gene in the RDP genome, which is essential for coronavirus replication and assembly, we constructed cell lines that express N protein with a lentivirus transducing system to trans-complement the N protein. The verification of theses cell lines was verified by RT-PCR (Fig. 1F). The expression of N in Caco-2-N cells was crucial for the RDP system. To ensure the expression level and consistency, we monitored N expression of Caco-2-N cells every five passages until the 20th passage. To benchmark the expression stability, we compared the Caco-2-N cells with the Caco-2-N-IRES-mCherry cells mentioned previously (Ju et al., 2021). The results showed that the percentage of mCherry positive cells of our constructed cells was maintained above 95% in 20 passages. In contrast, the positive cell percentage of Caco-2-N-IRES-mCherry cells significantly decreased after the 10th passage (Fig. 1G). This suggested that our constructed Caco-2-N cells can consistently express the N protein for at least 20 passages.

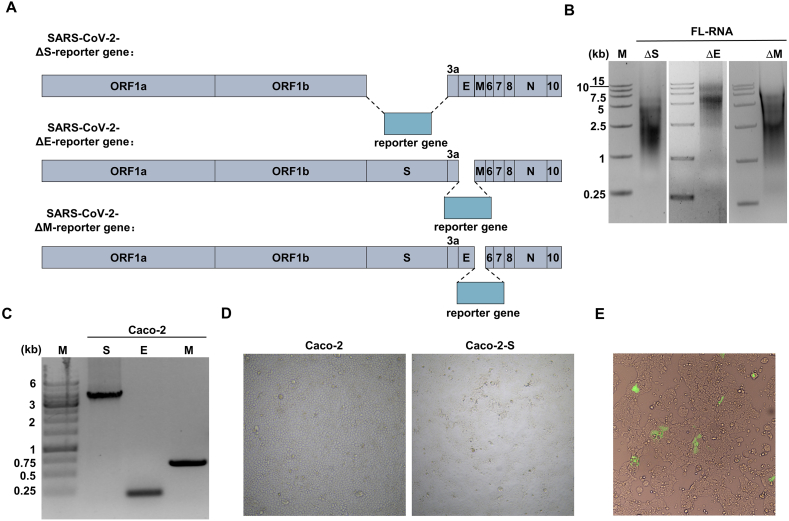

Trans-complementary system lacking S or E-ORF3 have also been reported (Ricardo-Lax et al., 2021; Zhang X. et al., 2021; Cheung et al., 2022). Following the same method mentioned above, we attempted to construct the trans-complementary system in which the S, E and M were replaced by the reporter gene, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1A). The resulting IVT mRNAs were analyzed in the agarose gel (Supplementary Fig. S1B). We also constructed Caco-2 cells that express the corresponding protein and verified the cells by RT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. S1C). Notably, we observed cell-cell fusion when lentivirus-S transduced the Caco-2 cells (Supplementary Fig. S1D).

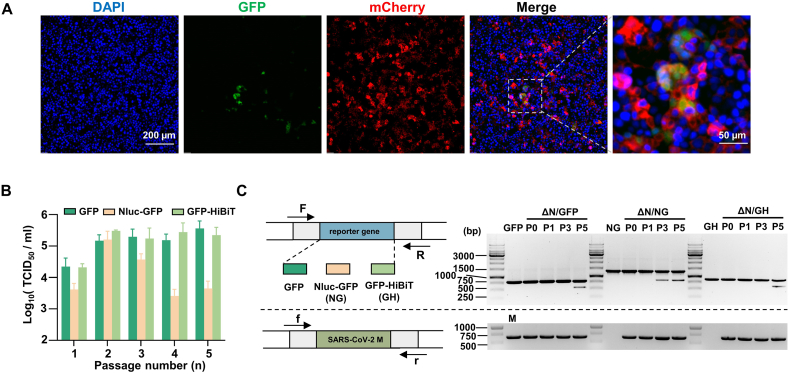

3.2. Rescue of RDPs, and optimization and stability of SARS-CoV-2 reporter RDPs

For maximum efficiency of rescue, approximately 20 μg SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-reporter gene full-length mRNA and 20 μg N mRNA were co-electroporated into Caco-2-N cells. GFP signals were observed 24 h post-electroporation (Fig. 2A). However, we didn't successfully rescue the RDP that lacking E and M on Caco-2 cells. GFP signals were observed after electroporation of SARS-CoV-2 ΔS-reporter gene full-length mRNA, but the observed cell-cell fusion would interfere with subsequent experiments (Supplementary Fig. S1E). Therefore, we selected the SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-reporter RDP system for further optimization. We selected two dual reporter genes, Nluc-GFP and GFP-HiBiT, both possessing GFP signals and luciferase activities. To assess the stability of SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-Nluc-GFP and SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDPs, we continuously passaged the RDPs on Caco-2-N cells for five rounds after electroporation. As previous research utilized GFP (Ju et al., 2021), we included SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP as a control. The titers of P0–P5 RDPs were measured by infecting Caco-2-N cells (Fig. 2B). The results showed an increase in titer for SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT and SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP RDPs after P0 RDP infection, reaching ∼105 TCID50/mL, and the titer remained relatively stable and high until P5. The titer of SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-Nluc-GFP RDP reached up to ∼105 TCID50/mL at P2 but decreased thereafter. Meanwhile, we examined the stability of the reporter genes. The P0, P1 and P5 RDP viral RNAs were extracted, and the reporter genes were detected using RT-PCR, with the M gene set as a control (Fig. 2C). The resulting bands of P1–P4 SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP and SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDPs were of the same size as the control band, while truncated fragments were observed in P5 RDPs. However, the RT-PCR bands of SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-Nluc-GFP RDP exhibited a small truncated band since P3 SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-Nluc-GFP RDPs. This suggested that SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP and SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDPs can propagate in Caco-2-N cells, producing higher titer than SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-Nluc-GFP RDP. Furthermore, the GFP and GFP-HiBiT reporter genes performed greater stability than the Nluc-GFP reporter gene in the ORF of N gene. This may be mainly due to the larger size of Nluc-GFP reporter gene. Taken together, considering the stable dual reporter gene signal of SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT, which is comparable to the GFP gene, and the relatively high titer, we selected this reporter RDP for the subsequent experiments.

Fig. 2.

RDP rescue, and optimization and stability of SARS-CoV-2 reporter RDP. A The GFP signal of electroporated Caco-2-N cells. Scale bar is indicated. B Continuously passaging the SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP, SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-Nluc-GFP and SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDPs on Caco-2-N cells for five rounds, and the titer of P0–P5 RDPs were determined. C RT-PCR analysis of the stability of the reporter genes of P0, P1 P3 and P5 SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP, SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-Nluc-GFP and SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDPs, respectively (top panel). The SARS-CoV-2 M gene was set as an internal reference (bottom panel). The scheme of the RT-PCR was indicated at the left, and the agarose gels of PCR products were shown at the right. GFP, Nluc-GFP (NG), GFP-HiBiT (GH) and SARS-CoV-2 M (M) fragments were performed as controls, respectively. The 1 kb DNA ladder is indicated.

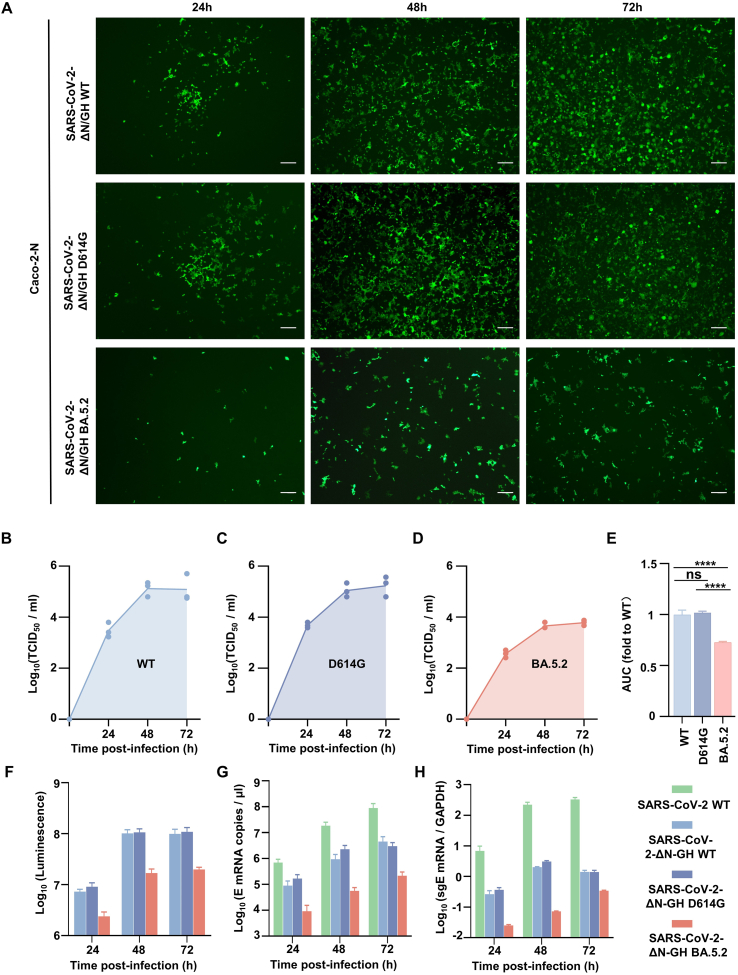

3.3. The characterization of SARS-CoV-2 reporter RDP

Two spike gene mutant RDPs (D614G and BA.5.2) were constructed in the same method. Caco-2-N cells were infected with those three RDPs (WT, D614G and BA.5.2) and authentic SARS-CoV-2 WT at MOI 0.05. The titer, GFP and luciferase signals were measure at the indicated time (Fig. 3A–F). The titer increased within 48 h and reached its peak. The titer of SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT BA.5.2 was much lower than that of WT and D614G (Fig. 3B–E). The fluorescent signals increased over time, reaching peak at 48–72 h (Fig. 3F). The luciferase signals showed a similar trend to the fluorescent signals, except for a slight decrease in the luciferase signals of WT and D614G at 72 h due to the occurrence of severe CPEs. The fluorescent and luciferase signals of SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT BA.5.2 RDP were much weaker because the BA5.2 S protein exhibit attenuated cell fusion (Park et al., 2023). To further confirmed the replication of RDP in Caco-2-N cells and compare it with authentic SARS-CoV-2, we quantified the sub-genomic E (sgE) mRNA of the infected cells and viral RNA (E) copies in the supernatant using RT-qPCR (Fig. 3G, H). Although the kinetics levels of sgE and E RNA of SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP were not as the same as the authentic SARS-CoV-2, which is expected, the trend was similar. Moreover, within the RDP, the RNA lever showed a high positive correlation with the fluorescent and luciferase signals. It indicates that the RDP system can mimic the authentic virus to some extends.

Fig. 3.

Stability and characterization of SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP. A The fluorescence of the SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT wild type (WT) and mutant (D614G and S-BA.5.2) RDPs infected cells. Scale bar, 200 μm. B–D Kinetics of titer and (E) the area under the curve were analyzed. Statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001; ns, not significant, P > 0.05. Kinetics of the luminescence (F), SARS-CoV-2 E mRNA level (G) and sub-genome E (sgE) mRNA copy (H). Caco-2 cells were infected with authentic SARS-CoV-2 WT (authentic WT). Caco-2-N cells were infected with the SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT wild type (WT) and mutant (D614G and S-BA.5.2) RDPs, respectively. Caco-2-N cells were infected at MOI 0.05. At the given time points, cells were harvested for luciferase signal measurement. Viral sgE mRNAs in the infected cells and viral/RDP yield in the infected cell supernatants was quantified by RT-qPCR.

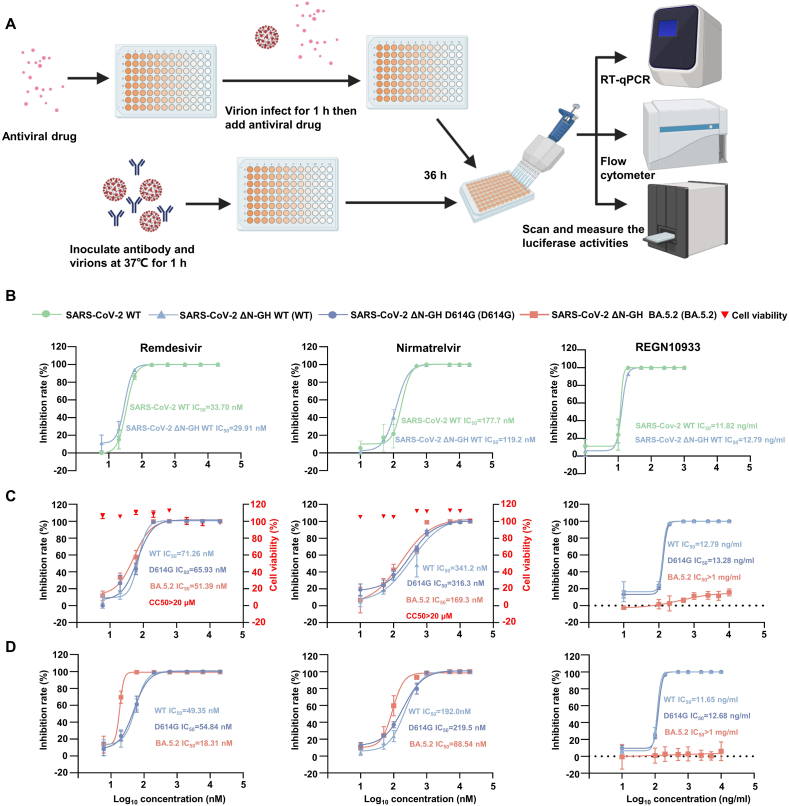

3.4. Antiviral drugs and neutralization evaluation in vitro

We applied the SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP to evaluate antiviral drugs, and the assay scheme in a 96-well plate is outlined in Fig. 4A. Initially, we conducted a comparative antiviral evaluation with authentic SARS-CoV-2 WT and SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT WT RDP using RT-qPCR. Three different compounds were tested: remdesivir (RDV, RdRp inhibitor), nirmatrelvir (3CLpro inhibitor, main component of Paxlovid) and REGN10933 (monoclonal antibody). As showed in the results (Fig. 4B), the IC50 curves for authentic virus and RDP were highly similar, with almost identical IC50 values. Next, we examined those three compounds using SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-Nluc-GFP WT and S mutants (D614G, BA5.2) RDPs. Since there were two reporter genes, we measured the GFP signal with flow cytometer and luciferase signal separately. Those three compounds inhibited the GFP signal and luciferase activities of those three SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDPs. When measuring luciferase activities, the IC50 values for RDV and nirmatrelvir against the SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT WT RDP were 71.26 nmol/L and 341.2 nmol/L, respectively (Fig. 4C). These two compounds exhibited similar IC50 for SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT D614G RDP (65.93 nmol/L of RDV, 316.3 nmol/L of nirmatrelvir). RDV and nirmatrelvir showed IC50 values of 51.39 nmol/L and 169.3 nmol/L, respectively, for SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT BA.5.2 RDP. When detecting the GFP signal, the IC50 values slightly decreased. The IC50 of RDV against SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT WT, D614G and BA.5.2 RDPs were 49.35 nmol/L, 54.84 nmol/L and 18.31 nmol/L, respectively. Nirmatrelvir showed an IC50 of 192.0 nmol/L, 219.5 nmol/L and 88.54 nmol/L for SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT WT, D614G and BA.5.2 RDPs, respectively (Fig. 4D). In the cytotoxicity assay, both RDV and nirmatrelvir demonstrated a CC50 of >10 μmol/L in Caco-2-N cells (Fig. 4B). For neutralizing antibody REGN10933 (Fig. 4C, D), regardless of which reporter gene signal was measured, the IC50 for SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT WT and D614G RDPs were quite similar. Overall, it suggests that SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP is a suitable tool for antiviral drug and neutralization antibody evaluation. Additionally, it has shown adaptability to variant coronavirus research. Moreover, the RDP demonstrated feasibility in replacing authentic virus for antiviral evaluations. The presence of GFP and luciferase activities in the RDP make it convenient for high-through screening of antiviral drugs.

Fig. 4.

High-throughput antiviral evaluation using SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP. A Antiviral drugs evaluation assay scheme in a 96-well format. Remdesivir (left panel), nirmatrelvir (middle panel) and REGEN10933 (right panel) were evaluated. B Comparison of drugs evaluation between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT WT RDP by RT-qPCR. The drugs were evaluated in SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT WT and mutant RDPs by measuring luminescence signal (C) and GFP signal (D), respectively. Cytotoxicity of these drugs to Caco-2-N cells was measured by CCK-8 assays. The left and right Y-axis of the graphs represent mean % inhibition of luciferase signal and cytotoxicity of the drugs, respectively. The experiments were done in triplicates. Dates are normalized to infected cells without antiviral drugs or antibody. The four-parameter dose-response curve was fitted using nonlinear regression method. The IC50 was calculated by Prism GraphPad and indicated.

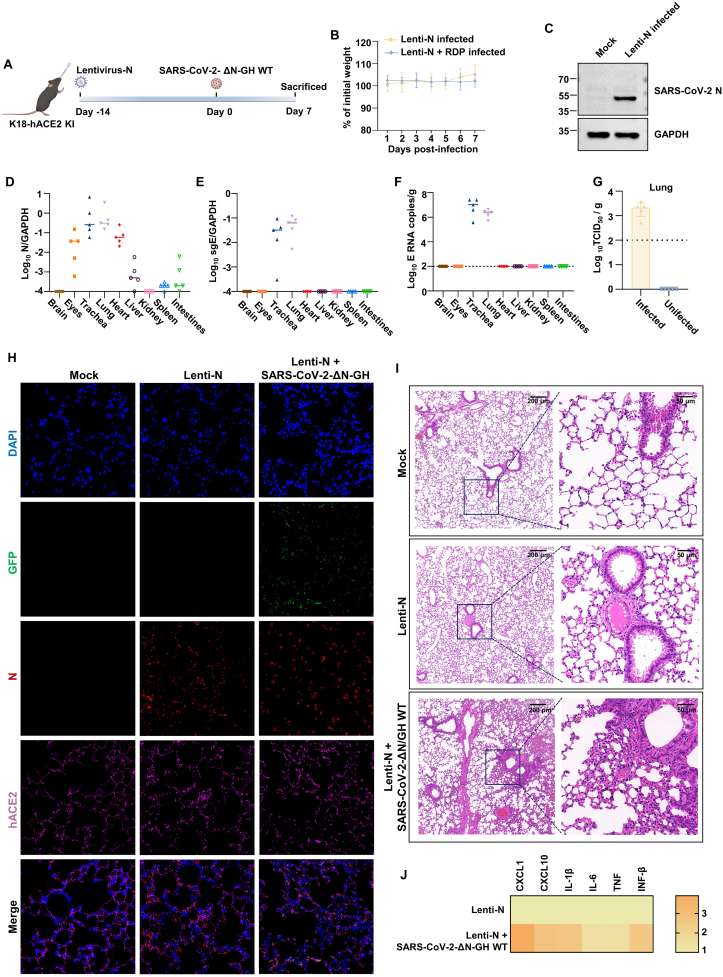

3.5. Construction of a preliminary SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP infection mice model

To assess the feasibility of constructing a RDP infected mice model, we generated K18-hACE2 KI mice expressing the SARS-CoV-2 N protein in lungs through intranasal inoculation with 2 × 109 copies lentivirus-N (Fig. 5A). After an additional 14 days, we collected the tissues to detect the expression of N. The N protein can be detected in the lungs of lentivirus-N infected mice (Fig. 5C, H), and the N RNA level was measured in the trachea, eyes, lungs and heart (Fig. 5D). Following a 14-day recovery, the lentivirus-N-infected mice were intranasally inoculated with 4 × 106 TCID50 SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP (the available highest infection dose). The RDP infected mice didn't lose weight (Fig. 5B) and showed no visible symptoms. Viral E sub-genome and E RNA were detected in the trachea and lungs of RDP infected mice, and it indicated that RDP replicate in the trachea and lungs (Fig. 5E, F). Moreover, the viral titer was detected in the lungs of infected mice, further confirming the ability of the virus to replicate in the lungs (Fig. 5G). Immunofluorescence analysis showed the presence of GFP in the lungs of SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP infected mice (Fig. 5H). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed pathological changes in the lung of RDP infected mice, such as peribronchial and perivascular to interstitial inflammatory infiltration (Fig. 5I). Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP infection induced an innate immune response in the lung cells (Fig. 5J). In summary, we have established a preliminary RDP infected mice model and provided guidance for subsequent construction of SARS-CoV-2 N transgene mice on the background of K18-hACE2 KI mice.

Fig. 5.

Construction of a preliminary SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP infection model through lentivirus-N. A The experiment schemes. The K18-hACE2 KI mice were intranasally infected with 2 × 109 copies lentivirus-N and feed for another 14 days. Then the lentivirus-N infected mice were intranasally infected with 4 × 106 TCID50 SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDPs. Mouse body weight was monitored for up to 7 days post-infection and all the mice were sacrificed at 7 days post-infection. B Body weight change of lentivirus-N infected mice and lentivirus-N + SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP infected mice. C WB was used to detect the expression of N protein in lung of lentivirus-N infected mice. D The N mRNA expression levels in lentivirus-N infected mice tissues were measured using RT-qPCR. E–F The sgE mRNA expression levels and viral genome copies in RDP-infected mice tissues were measured using RT-qPCR. G The viral titers in lungs of RDP-infected and uninfected lentivirus-N-transduced mice were measured using TCID50 method. Each dot represents one mouse (n = 5). The relative RNA expression was normalized to GAPDH. H–I Immunofluorescence analysis and pathological changes in lungs of mock, lentivirus-N and lentivirus-N + SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP infected mice, respectively. J Heat map of cytokines and chemokines in lungs of infected mice.

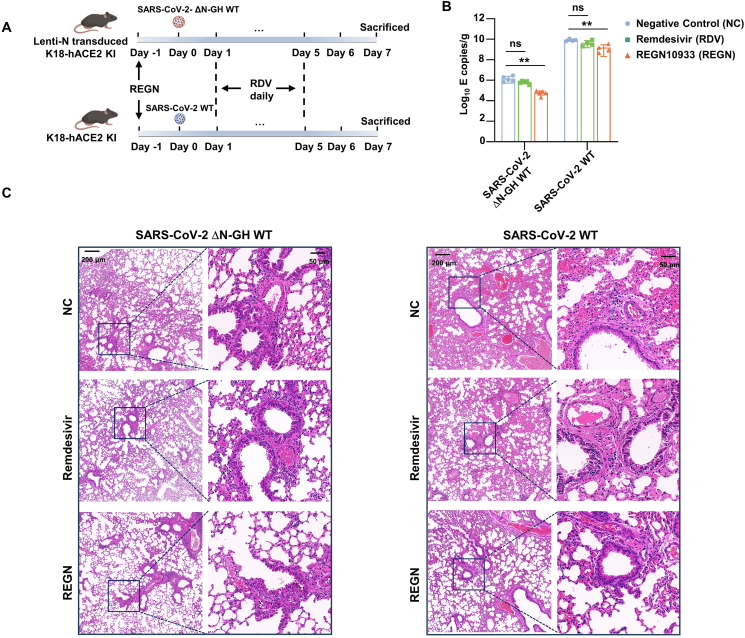

3.6. Evaluate the antiviral drug and neutralizing antibody in vivo

To validate the applicability of constructed mouse model for the evaluation of antiviral drug and neutralizing antibodies, RDV and REGN10933 were selected for testing. The lentivirus-N transduced K18-hACE2 KI mice were infected with 4 × 106 TCID50 SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP, while K18-hACE2 KI mice were inoculated with 250 PFU authentic SARS-CoV-2 WT. In the RDV group, the mice were subcutaneously treated with 25 mg/kg RDV daily from 1 dpi to 5 dpi. For REGN10933 prophylactic treatment, the mice were injected at does of 10 mg/kg REGN10933 one day before infection (Fig. 6A). At 7 dpi, all mice were sacrificed and the viral RNA level in the lung was measured. Although the viral RNA copies in the lungs of SARS-CoV-2 authentic WT infected-mice were much higher than those of RDP-infected mice, both mice model performed similar results in the assessment of the two drugs. It showed that RDV treatment did not lead to significant decrease in the viral RNA level in the lungs, while REGN10933 treatment resulted in a significant decrease compared to the NC group mice (Fig. 6B). Consistent with the RT-qPCR results, lung pathology analysis showed milder lung lesions in RDP-infected mice. It also showed obvious interstitial pneumonia, characterized by large numbers of inflammatory cells infiltrating into the lungs and the wide thickening alveolar septum in the lungs of NC and RDV groups. In contrast, only limited inflammatory cells infiltration was observed in REGN10933 treated mice (Fig. 6C). These results demonstrate the suitability of our constructed mouse model for in vivo evaluation of antiviral drugs and its ability to mimic the authentic virus in antiviral evaluation.

Fig. 6.

Evaluate the antiviral drug and neutralizing antibody in vivo. A The scheme of evaluation of remdesivir (RDV) and REGN10933 (REGN) in vivo. The time of RDV and REGN treatment was indicated in the illustration. The RDP and authentic SARS-CoV-2 infected mice are indicated at top and bottom panel, respectively. B The viral RNA copies in the lung were measured at 7 dpi. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed, unpaired t-test. ∗∗P < 0.01; ns, not significant, P > 0.05. C Section of paraffin embedded lungs from mock, RDV and REGN group mice were stained with hematoxylin/eosin. The scale bar is indicated.

4. Discussion

The reverse genetic systems are powerful techniques for manipulating RNA viruses, such as flavivirus and coronavirus. However, constructing the coronavirus genome into commonly used bacterial vector is challenging due to its large size and instability hindering the rescue of coronavirus. To address this issue, several strategies have been employed to construct coronavirus full-length cDNA. One widely adopted vector is the bacterial chromosome (BAC) vector, which strictly controls the copy number and eliminates the toxicity and instability of the viral genome fragment to the host cell (Almazán et al., 2000; Jin et al., 2021). The BAC-launched method has been successful rescued several coronaviruses by inserting the CMV promoter and hepatitis delta virus ribozyme (HDVr) -bovine growth hormone (BGH) terminator upstream and downstream of the full-length viral cDNA, respectively (Ye et al., 2020; Rihn et al., 2021). Another rapid approach for generating viral full-length cDNA is the in vitro ligation method. This method involves constructing continuous viral genome fragments into bacterial plasmids, which are then separated by type IIS restriction endonucleases and ligated using T4 ligase to achieve seamless ligation of viral full-length cDNA (Hou et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2020). Recently, yeast transformation-associated recombination (TAR) cloning has been applied in rescuing SARS-CoV-2 (Thi Nhu Thao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Cai and Huang, 2023). The TAR-based method has showed to be highly accurate and efficient in assembling viral full-length cDNA. Furthermore, the viral genome can be divided into smaller continuous fragments, facilitating manipulation without significantly impacting the assembly efficiency (Thi Nhu Thao et al., 2020). However, caution should be exercised when selecting the homologous “hook” sequence, as factors such as high GC content and repeated-enriched sequences can decrease the recombination efficiency in the yeast (Kouprina and Larionov, 2006).

Replicon is commonly used tool for researching infectious viruses in BSL-2 laboratories. Various types of replicons have been reported for SARS-CoV-2 (He et al., 2021; Jin et al., 2021; Ju et al., 2021; Ricardo-Lax et al., 2021; Zhang X. et al., 2021; Zhang Y. et al., 2021; Cheung et al., 2022; Feng et al., 2022; Tanaka et al., 2022). These replicons are primarily based on the BAC vector, where one or more structural gene (S, E or M) are replaced with a reporter gene, excluding the N gene. The resulting replicon is usually one-shoot without intact virion secreted. Another type of system is the trans-complementation virus-like particle/RDP, whose genome lacks a certain structural gene (S, ORF3-E or N) while simultaneously trans-complementing the corresponding structural protein in the host cell (Ju et al., 2021; Ricardo-Lax et al., 2021; Zhang X. et al., 2021; Cheung et al., 2022; Malicoat et al., 2022). The trans-complementation virus-like particle/RDP exhibit robust applications in SARS-CoV-2 research.

Here, we attempted to construct ΔS, ΔM, ΔE and ΔN trans-complementary RDPs, but we failed to rescue ΔM and ΔE RDPs. Moreover, as the S protein can bind with the ACE2 receptor, the lentivirus-S transduced Caco-2 cells exhibit cell-cell fusion, which is a hindrance in application, especially in application such as neutralizing antibody evaluation (Supplementary Fig. S1D). Therefore, it is recommended to utilize this RDP as a one-shot approach, as reported previously (Ricardo-Lax et al., 2021; Cheung et al., 2022). Furthermore, we made some improvements to the SARS-CoV-2 ΔN reporter RDP based on the reported trans-complement virus-like particle/RDP (Ju et al., 2021; Cheung et al., 2022). We replaced the ORF of N with the dual reporter gene (GFP-HiBiT), which exhibits the additional luciferase activity and is more convenient for high-throughput antiviral screening (Fig. 3F). To prevent dilution and loss of N during cell passage, the resistance gene was integrated into the host cell genome. The constructed cell line overexpressing N exhibited high expression stability for at least 20 passages under puromycin pressure (Fig. 1G). Theoretically, the SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT reporter RDP can amplify in the cells that express hACE2 and SARS-CoV-2 N. We conducted experiments with several widely used cell lines, including Vero E6-N, Calu-3-N, and BHK-21-N/hACE2. The RDPs exhibited the ability to infect these cells at a higher MOI (MOI = 0.1–0.5), however, the GFP signals observed were weak. Moreover, the titers of progeny RDPs in these cells were much lower compared to those in Caco-2-N cells. In some cases, we were unable to detect the titer of progeny RDPs. The poor titer significantly complicates the assay process. Ultimately, we found that Caco-2-N cells consistently provide the ideal titer if progeny RDPs among the tested cell lines. Considering these factors, we conducted most assays using Caco-2-N cells. The reason for the proliferation difference in cells expressing hACE2 and SARS-CoV-2 N proteins remains unclear, but we speculate that it may be due to the different expression levels of proteases on the cell surface and the folding of the N protein on different cells. The titer of SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP remained high after successive passages. However, due to the truncation of reporter genes after several rounds of infections, it may influence the GFP signals to some extend in different reporter genes. The impact is greater if the inserted reporter gene is longer. Notably, the Nluc-GFP, being the longest reporter gene among the selected reporter genes, showed greater instability. It was reflected in the attenuated SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-Nluc-GFP titers since the 3rd round of infection. For the shorter reporter genes, the truncation occurred later, and the titers of those RDPs appear to be influenced less within 5 rounds of infection.

Our RDP can mimic entire cycle of the virus infection confined to the permissive cells. It is superior to the BAC-launched replicons, which miss the process of virus entry and are not suitable for screening of neutralizing antibody. Additionally, although the BAC-launched replicons show does-dependent repression in response to antiviral drugs, recent reports indicate the resistance to antiviral treatment (Nguyen et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022). Although not extensively explained, we speculate that the continuous and robust transcription driven by the CMV promoter, which remains unaffected by antiviral treatment, might contribute to this resistance. In contrast, our RDP propels the entire viral cycle independently, without relying on exogenous promoters, making it is more sensitive to antiviral treatment and close to authentic virus. Our results indicated that the kinetics of viral RNA levels are closely resemble those of authentic SARS-CoV-2 when measured using RT-qPCR. The calculated IC50 values of RDV, nirmatrelvir and RGEN10933 were quite similar between the authentic virus and the RDP. When evaluating the antiviral drugs using RDP with different reporter genes, minor fluctuations were observed, likely due to the varying sensitivity in detection methods and system errors. However, the IC50 of neutralizing antibody (REGN10933) remained consistent across different reporter genes, highlighting the superiority of our RDPs system in evaluating neutralizing antibodies.

The transgenic mouse model susceptible to infection by trans-complemental virus-like particles have been previously reported by Yang et al. (2023). It provided a very powerful mice model for the research of SARS-CoV-2. In our study, we attempted to construct a lentivirus-N transduced mouse expressing the N protein, which is inspired by the construction of AAV/hACE2 mouse model (Sun et al., 2021). We detected the expression of N in the lung 14 days post lentivirus-N infection. Our research demonstrated that lentivirus-N infected mice can support RDP replication and trigger pathological alterations. This approach proves cost-effective and allows for the rapid generation of target mice. However, delivering the N protein with lentivirus has several drawbacks. Firstly, this method necessitates intranasal infection of the mice with lentivirus-N in advance, which is stressful for the mice. Moreover, the distribution of N protein may extend to the eyes via intranasal inoculation and reach the heart through cardiopulmonary circulation. The observed lower N RNA level in the liver suggests a potential transfer of lentivirus-N to the liver via systemic circulation. It leads to an uneven distribution of N protein among tissues and mice. Additionally, the lentivirus itself has an impact on the lung pathology of mice. It has been reported that the SARS-CoV-2 N protein can cause pulmonary fibrosis in the lung (Chen et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023). To eliminate the impact of lentivirus transduction and the uneven expression of N amongst mice, the optimal strategy was to generate the transgenic mice that express N in the background of K18-hACE2. The method highlighted in this article can provide a preliminary exploration and supports the optimal construction of the transgenic mice.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have established an optimized trans-complement SARS-CoV-2 ΔN-GFP-HiBiT RDP system for high-throughput antiviral screening. Moreover, we have explored and generated a RDP infected mice model. This RDP system can be manipulated in a BSL-2 laboratory and applied to study the coronavirus characteristics, replication/transcription, and virus–host cell interaction.

Data availability

All the data generated during the current study are included in the manuscript.

Ethics statement

The protocols and procedures for handling infectious SARS-CoV-2 authentic virus in the Animal Biosafety Level III Laboratory (ABSL-III Lab) facility were approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC) at Wuhan University (WP20220044). To evaluate the biosafety, the RDP experiments were initially performed in the ABSL-III Lab. After determining that there was no biological risk, they were approved to be carried out in the ABSL-II Lab at State Key Laboratory of Virology. The protocols and procedures for handling lentivirus and SARS-CoV-2 RDP in the ABSL-II Lab facility were approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee at State Key Laboratory of Virology (SKLV-AE2023 007). All the samples were inactivated according to IBC-approved standard procedures for the removal of specimens from high containment.

Author contributions

Yingjian Li: conceptualization, methodology, software, date curation and writing-original draft preparation. Xue Tan: methodology, software and date curation. Jikai Deng: methodology and software. Xuemei Liu: methodology. Qianyun Liu: methodology and software. Zhen Zhang: methodology. Xiaoya Huang: methodology. Shen Chao: writing-reviewing and editing. Ke Xu: conceptualization investigation and funding acquisition. Li Zhou: methodology, investigation, writing-reviewing and editing, and funding acquisition. Yu Chen: investigation, supervision, writing-reviewing and editing, and funding acquisition.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Qiang Ding and laboratory members Xiaohui Ju and Yangying Yu from Tsinghua University in Beijing, China for technical advice in the rescue of SARS-CoV-2 ΔN reporter RDP. This study was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1300801 and 2018YFA0900801), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82172243 and 82372223) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2042021kf0220 and 2042022dx0003).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virs.2024.03.009.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

figs1.

References

- Almazán F., González J.M., Pénzes Z., Izeta A., Calvo E., Plana-Durán J., Enjuanes L. Engineering the largest RNA virus genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:5516–5521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Z., Cao Y., Liu W., Li J. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein and its role in viral structure, biological functions, and a potential target for drug or vaccine mitigation. Viruses. 2021;13:1115. doi: 10.3390/v13061115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao L., Deng W., Huang B., Gao H., Liu J., Ren L., Wei Q., Yu P., Xu Y., Qi F., Qu Y., Li F., Lv Q., Wang W., Xue J., Gong S., Liu M., Wang G., Wang S., Song Z., Zhao L., Liu P., Zhao L., Ye F., Wang H., Zhou W., Zhu N., Zhen W., Yu H., Zhang X., Guo L., Chen L., Wang C., Wang Y., Wang X., Xiao Y., Sun Q., Liu H., Zhu F., Ma C., Yan L., Yang M., Han J., Xu W., Tan W., Peng X., Jin Q., Wu G., Qin C. The pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 in hACE2 transgenic mice. Nature. 2020;583:830–833. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2312-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H.L., Huang Y.W. Reverse genetics systems for SARS-CoV-2: development and applications. Virol. Sin. 2023;38:837–850. doi: 10.1016/j.virs.2023.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Guan W.J., Qiu Z.E., Xu J.B., Bai X., Hou X.C., Sun J., Qu S., Huang Z.X., Lei T.L., Huang Z.Y., Zhao J., Zhu Y.X., Ye K.N., Lun Z.R., Zhou W.L., Zhong N.S., Zhang Y.L. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein triggers hyperinflammation via protein-protein interaction-mediated intracellular Cl(-) accumulation in respiratory epithelium. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022;7:255. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01048-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Liu Q., Guo D. Emerging coronaviruses: genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:418–423. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung P.H., Ye Z.W., Lui W.Y., Ong C.P., Chan P., Lee T.T., Tang T.T., Yuen T.L., Fung S.Y., Cheng Y., Chan C.P., Chan C.P., Jin D.Y. Production of single-cycle infectious SARS-CoV-2 through a trans-complemented replicon. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94:6078–6090. doi: 10.1002/jmv.28057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X., Zhang X., Jiang S., Tang Y., Cheng C., Krishna P.A., Wang X., Dai J., Zeng J., Xia T., Zhao D. A DNA-based non-infectious replicon system to study SARS-CoV-2 RNA synthesis. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022;20:5193–5202. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2022.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan A.O., Case J.B., Winkler E.S., Thackray L.B., Kafai N.M., Bailey A.L., Mccune B.T., Fox J.M., Chen R.E., Alsoussi W.B., Turner J.S., Schmitz A.J., Lei T., Shrihari S., Keeler S.P., Fremont D.H., Greco S., Mccray P.B., Jr., Perlman S., Holtzman M.J., Ellebedy A.H., Diamond M.S. A SARS-CoV-2 infection model in mice demonstrates protection by neutralizing antibodies. Cell. 2020;182:744–753.e744. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Quan S., Xu M., Rodriguez S., Goh S.L., Wei J., Fridman A., Koeplinger K.A., Carroll S.S., Grobler J.A., Espeseth A.S., Olsen D.B., Hazuda D.J., Wang D. Generation of SARS-CoV-2 reporter replicon for high-throughput antiviral screening and testing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2025866118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y.J., Okuda K., Edwards C.E., Martinez D.R., Asakura T., Dinnon K.H., 3rd, Kato T., Lee R.E., Yount B.L., Mascenik T.M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 reverse genetics reveals a variable infection gradient in the respiratory tract. Cell. 2020;182:429–446.e414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., Guo H., Zhou P., Shi Z.L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19:141–154. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang R.D., Liu M.Q., Chen Y., Shan C., Zhou Y.W., Shen X.R., Li Q., Zhang L., Zhu Y., Si H.R., Wang Q., Min J., Wang X., Zhang W., Li B., Zhang H.J., Baric R.S., Zhou P., Yang X.L., Shi Z.L. Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 in transgenic mice expressing human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Cell. 2020;182:50–58.e58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y.Y., Lin H., Cao L., Wu W.C., Ji Y., Du L., Jiang Y., Xie Y., Tong K., Xing F., Zheng F., Shi M., Pan J.A., Peng X., Guo D. A convenient and biosafe replicon with accessory genes of SARS-CoV-2 and its potential application in antiviral drug discovery. Virol. Sin. 2021;36:913–923. doi: 10.1007/s12250-021-00385-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju X., Zhu Y., Wang Y., Li J., Zhang J., Gong M., Ren W., Li S., Zhong J., Zhang L., Zhang Q.C., Zhang R., Ding Q. A novel cell culture system modeling the SARS-CoV-2 life cycle. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouprina N., Larionov V. TAR cloning: insights into gene function, long-range haplotypes and genome structure and evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:805–812. doi: 10.1038/nrg1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Zhao H., Li Z., Zhang Z., Huang R., Gu M., Zhuang K., Xiong Q., Chen X., Yu W., Qian S., Zhang Y., Tan X., Zhang M., Yu F., Guo M., Huang Z., Wang X., Xiang W., Wu B., Mei F., Cai K., Zhou L., Zhou L., Wu Y., Yan H., Cao S., Lan K., Chen Y. Broadly neutralizing antibodies derived from the earliest COVID-19 convalescents protect mice from SARS-CoV-2 variants challenge. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023;8:347. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01615-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malicoat J., Manivasagam S., Zuñiga S., Sola I., Mccabe D., Rong L., Perlman S., Enjuanes L., Manicassamy B. Development of a single-cycle infectious SARS-CoV-2 virus replicon particle system for use in biosafety level 2 laboratories. J. Virol. 2022;96 doi: 10.1128/jvi.01837-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H.T., Falzarano D., Gerdts V., Liu Q. Construction of a noninfectious SARS-CoV-2 replicon for antiviral-drug testing and gene function studies. J. Virol. 2021;95 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00687-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.B., Khan M., Chiliveri S.C., Hu X., Irvin P., Leek M., Grieshaber A., Hu Z., Jang E.S., Bax A., Liang T.J. SARS-CoV-2 omicron variants harbor spike protein mutations responsible for their attenuated fusogenic phenotype. Commun. Biol. 2023;6:556. doi: 10.1038/s42003-023-04923-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo-Lax I., Luna J.M., Thao T.T.N., Le Pen J., Yu Y., Hoffmann H.H., Schneider W.M., Razooky B.S., Fernandez-Martinez J., Schmidt F., Weisblum Y., Trüeb B.S., Berenguer Veiga I., Schmied K., Ebert N., Michailidis E., Peace A., Sánchez-Rivera F.J., Lowe S.W., Rout M.P., Hatziioannou T., Bieniasz P.D., Poirier J.T., Macdonald M.R., Thiel V., Rice C.M. Replication and single-cycle delivery of SARS-CoV-2 replicons. Science. 2021;374:1099–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.abj8430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rihn S.J., Merits A., Bakshi S., Turnbull M.L., Wickenhagen A., Alexander A.J.T., Baillie C., Brennan B., Brown F., Brunker K., et al. A plasmid DNA-launched SARS-CoV-2 reverse genetics system and coronavirus toolkit for COVID-19 research. PLoS Biol. 2021;19 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C.P., Jan J.T., Wang I.H., Ma H.H., Ko H.Y., Wu P.Y., Kuo T.J., Liao H.N., Lan Y.H., Sie Z.L., Chen Y.H., Ko Y.A., Liao C.C., Chen L.Y., Lee I.J., Tsung S.I., Lai Y.J., Chiang M.T., Liang J.J., Liu W.C., Wang J.R., Yuan J.P., Lin Y.S., Tsai Y.C., Hsieh S.L., Li C.W., Wu H.C., Ko T.M., Lin Y.L., Tao M.H. Rapid generation of mouse model for emerging infectious disease with the case of severe COVID-19. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashita E., Yamayoshi S., Halfmann P., Wilson N., Ries H., Richardson A., Bobholz M., Vuyk W., Maddox R., Baker D.A., Friedrich T.C., O'connor D.H., Uraki R., Ito M., Sakai-Tagawa Y., Adachi E., Saito M., Koga M., Tsutsumi T., Iwatsuki-Horimoto K., Kiso M., Yotsuyanagi H., Watanabe S., Hasegawa H., Imai M., Kawaoka Y. In vitro efficacy of antiviral agents against omicron subvariant BA.4.6. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;387:2094–2097. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2211845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T., Saito A., Suzuki T., Miyamoto Y., Takayama K., Okamoto T., Moriishi K. Establishment of a stable SARS-CoV-2 replicon system for application in high-throughput screening. Antiviral Res. 2022;199 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2022.105268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G., Liu Z., Chen D. Human coronaviruses: origin, host and receptor. J. Clin. Virol. 2022;155 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2022.105246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thi Nhu Thao T., Labroussaa F., Ebert N., V'kovski P., Stalder H., Portmann J., Kelly J., Steiner S., Holwerda M., Kratzel A., Gultom M., Schmied K., Laloli L., Hüsser L., Wider M., Pfaender S., Hirt D., Cippà V., Crespo-Pomar S., Schröder S., Muth D., Niemeyer D., Corman V.M., Müller M.A., Drosten C., Dijkman R., Jores J., Thiel V. Rapid reconstruction of SARS-CoV-2 using a synthetic genomics platform. Nature. 2020;582:561–565. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne L.G., Bouhaddou M., Reuschl A.K., Zuliani-Alvarez L., Polacco B., Pelin A., Batra J., Whelan M.V.X., Hosmillo M., Fossati A., et al. Evolution of enhanced innate immune evasion by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2022;602:487–495. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04352-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Zhang C., Lei X., Ren L., Zhao Z., Wang J., Huang H. Construction of non-infectious SARS-CoV-2 replicons and their application in drug evaluation. Virol. Sin. 2021;36:890–900. doi: 10.1007/s12250-021-00369-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Peng X., Jin Y., Pan J.A., Guo D. Reverse genetics systems for SARS-CoV-2. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94:3017–3031. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler E.S., Bailey A.L., Kafai N.M., Nair S., Mccune B.T., Yu J., Fox J.M., Chen R.E., Earnest J.T., Keeler S.P., Ritter J.H., Kang L.I., Dort S., Robichaud A., Head R., Holtzman M.J., Diamond M.S. SARS-CoV-2 infection of human ACE2-transgenic mice causes severe lung inflammation and impaired function. Nat. Immunol. 2020;21:1327–1335. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0778-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu A., Peng Y., Huang B., Ding X., Wang X., Niu P., Meng J., Zhu Z., Zhang Z., Wang J., Sheng J., Quan L., Xia Z., Tan W., Cheng G., Jiang T. Genome composition and divergence of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) originating in China. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:325–328. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X., Muruato A., Lokugamage K.G., Narayanan K., Zhang X., Zou J., Liu J., Schindewolf C., Bopp N.E., Aguilar P.V., Plante K.S., Weaver S.C., Makino S., Leduc J.W., Menachery V.D., Shi P.Y. An infectious cDNA clone of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:841–848.e843. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Liu C., Ju X., Wu B., Wang Z., Dong F., Yu Y., Hou X., Fang M., Gao F., Guo X., Gui Y., Ding Q., Li W. A tissue specific-infection mouse model of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Discov. 2023;9:43. doi: 10.1038/s41421-023-00536-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye C., Chiem K., Park J.G., Oladunni F., Platt R.N., 2nd, Anderson T., Almazan F., De La Torre J.C., Martinez-Sobrido L. Rescue of SARS-CoV-2 from a single bacterial artificial chromosome. mBio. 2020;11 doi: 10.1128/mBio.02168-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Fischer D.K., Shuda M., Moore P.S., Gao S.J., Ambrose Z., Guo H. Construction and characterization of two SARS-CoV-2 minigenome replicon systems. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94:2438–2452. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Liu Y., Liu J., Bailey A.L., Plante K.S., Plante J.A., Zou J., Xia H., Bopp N.E., Aguilar P.V., Ren P., Menachery V.D., Diamond M.S., Weaver S.C., Xie X., Shi P.Y. A trans-complementation system for SARS-CoV-2 recapitulates authentic viral replication without virulence. Cell. 2021;184:2229–2238.e2213. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Song W., Chen S., Yuan Z., Yi Z. A bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC)-vectored noninfectious replicon of SARS-CoV-2. Antiviral Res. 2021;185 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.Y., Ju C.Y., Wu L.Z., Yan H., Hong W.B., Chen H.Z., Yang P.B., Wang B.R., Gou T., Chen X.Y., Jiang Z.H., Wang W.J., Lin T., Li F.N., Wu Q. Therapeutic potency of compound RMY-205 for pulmonary fibrosis induced by SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. Cell Chem. Biol. 2023;30:261–277.e268. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2023.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Wong L.R., Li K., Verma A.K., Ortiz M.E., Wohlford-Lenane C., Leidinger M.R., Knudson C.M., Meyerholz D.K., Mccray P.B., Jr., Perlman S. COVID-19 treatments and pathogenesis including anosmia in K18-hACE2 mice. Nature. 2021;589:603–607. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2943-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated during the current study are included in the manuscript.