Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replicates primarily in lymphoid tissues where it has ready access to activated immune competent cells. We used one of the major pathways of immune activation, namely, CD40-CD40L interactions, to study the infectability of B lymphocytes isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Highly enriched populations of B lymphocytes generated in the presence of interleukin-4 and oligomeric soluble CD40L upregulated costimulatory and activation markers, as well as HIV-1 receptors CD4 and CXCR4, but not CCR5. By using single-round competent luciferase viruses complemented with either amphotropic or HIV-derived envelopes, we found a direct correlation between upregulation of HIV-1 receptors and the susceptibility of the B lymphocytes to infection with dual-tropic and T-tropic strains of HIV-1; in contrast, cells were resistant to M-tropic strains of HIV-1. HIV-1 envelope-mediated infection was completely abolished with either an anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody or a peptide known to directly block CXCR4 usage and partially blocked with stromal cell-derived factor 1, all of which had no effect on the entry of virus pseudotyped with amphotropic envelope. Full virus replication kinetics confirmed that infection depends on CXCR4 usage. Furthermore, productive cycles of virus replication occurred rapidly yet under most conditions, without the appearance of syncytia. Thus, an activated immunological environment may induce the expression of HIV-1 receptors on B lymphocytes, priming them for infection with selective strains of HIV-1 and allowing them to serve as a potential viral reservoir.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection is associated with continuous virus replication, immune cell hyperactivation, and progressive immune dysfunction (11). While the mechanisms responsible for the high degree of immune activation associated with HIV remain ill defined, it is clear that encounters between foreign antigen, antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and T cells contribute to this hyperactivity. One of the major regulatory pathways governing CD4+ T-cell-dependent immune responses consists of interactions between CD40 on APCs and CD40L on activated T cells, which result in the priming and expansion of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells, induction of costimulatory molecules on APCs, and the release of cytokines (16). Several elements of this pathway have been implicated in the spectrum of immunological dysfunctions associated with HIV-1 infection (5, 7, 39). Furthermore, CD40-induced stimulatory effects have recently been found to enhance the replication of HIV-1 in both APCs and CD4+ T cells (29, 30, 35); yet CD40-CD40L interactions have also been reported to induce the release of chemokines having suppressive effects on HIV-1 infection (18).

B lymphocytes are strongly regulated by CD40-CD40L interactions at the level of cell proliferation and activation, formation of germinal centers, heavy-chain class switching, and secretion of immunoglobulins (21). Numerous perturbations of the B-cell compartment have been associated with HIV-1 pathogenesis, including polyclonal B-cell activation, hypergammaglobulinemia, and follicular hyperplasia (19, 24, 27, 32). Some of these perturbations have been directly linked to defects in CD40-CD40L pathways (4, 24, 39). We have previously demonstrated that CD40-stimulated B lymphocytes can be productively infected with HIV-1 (31) and that this is in part associated with the induction of long-terminal-repeat (LTR)-responsive transcription factors, such as NF-κB (20). In the present study, we investigated the modulation of cell surface receptors that take place during CD40-mediated B-cell proliferation. We found that CD40 ligation leads to a progressive upregulation of surface markers CD4 and the T-tropic HIV-1 coreceptor, CXCR4. We show, concurrent with this enhanced expression, increased susceptibility to HIV-1 infection with T-tropic and dual-tropic strains of HIV-1. Our findings suggest that B cells may provide a potential reservoir for CXCR4-dependent strains of HIV-1 and may play an important role in disseminating virus during late-stage disease when CXCR4-using strains predominate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell purification and culture conditions.

B lymphocytes isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient separation were purified by using a cocktail of antibody-coated magnetic beads for B-cell enrichment according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada). Alternatively, the PBMCs were depleted of CD2-positive cells by using magnetic beads as described previously (31). B lymphocytes were seeded at 5 × 104 per well in 96-well culture plates in Iscove medium supplemented with 10% human serum (Gemini Bioproducts, Calabasas, Calif.), 5 μg of human transferrin (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) per ml, 5 μg of recombinant human insulin (Life Technologies) per ml, 200 U of human interleukin-4 (IL-4; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, N.J.) per ml, and 500 ng of soluble oligomeric CD40L per ml kindly provided by Immunex, Seattle, Wash. Alternatively, irradiated CD40L-transfected NIH 3T3 cells were used as a source of CD40L. CD8-depleted, anti-CD3 activated PBMCs were prepared as described previously (6).

Flow cytometric analysis.

The purity of B-cell cultures was verified with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- or phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) specific for CD19, CD3, CD14, and CD1a. For evaluation of activation markers, cells were double labeled with FITC-conjugated MAb for CD20 and with PE-conjugated MAbs specific for CD40L, CD80, or CD86. HIV-1 receptor expression was measured with the combination of FITC-conjugated MAb for CD20, PE-conjugated MAbs specific for human CCR5 or CXCR4, and Cy-Chrome-conjugated or PE-conjugated MAb specific for CD4. Antibodies to CD19, CD3, CD14, CD54, and CD20 were purchased from Becton Dickinson (Mountain View, Calif.). Antibodies to CD1a, CD80, CD86, CCR5, CXCR4, and CD4 were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.). Flow cytometric analyses of labeled cells were performed on an EPICS XL Flow cytometer (Coulter, Hialeah, Fla.).

For intracellular p24 analyses, the cells were stained and permeabilized (Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells first stained with FITC-conjugated MAb for CD19, followed by permeabilization and staining with the antibody KC57-PE (Coulter), which recognizes HIV p24gag antigen. Analyses were performed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

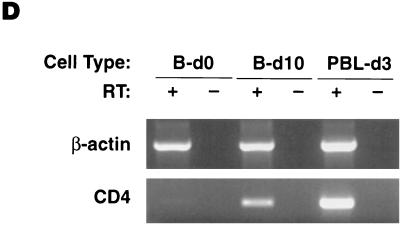

Detection of CD4 mRNA.

Total RNA was extracted from cells by using a silica gel-based purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) and treated with DNase according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. The RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed in 20 μl with 40 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (RT; Life Sciences, St. Petersburg, Fla.) and 300 ng of random hexamers (Life Technologies). The resulting cDNA (2 μl) was amplified by using 0.5 U of Ampli-TaqGold (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) and a specific primer (20 pmol each) set for either human CD4 or β-actin (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.). Amplified products were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Viruses and envelopes.

The following plasmids were obtained through the AIDS Reference and Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH): pNL4-3 Env(−) LUC(+) and JRFLenv from Nathaniel Landau, SV-A-MLV-env from Nathaniel Landau and Dan Littman, and pNL4-3 from Malcolm Martin. The plasmid pTEJ8-SD-envSF33 (23), a generous gift from Louise Poulin (Université Laval, Ste-Foy, Quebec, Canada), was derived from the plasmid SF33-3′, graciously provided to Louise Poulin by Jay Levy (Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco). Chimeric envelopes bearing the tropism of 89.6 and JRFL were generated from pTEJ8-SD-envSF33 by substituting the SF33 envelope KpnI-MunI region (nucleotides 606 to 1897 from the sequence in GenBank [accession number M38427]) with that of 89.6 and JRFL. The tropism of these envelopes was verified by infecting U87/CD4/CXCR4 and U87MG/CD4/CCR5 with luciferase viruses pseudotyped with the respective envelopes.

A panel of HIV-1 molecular clones was assembled from generous gifts provided by the following people: Keith Peden (Food and Drug Administration, Bethesda, Md.) for ELI1 and ELI6, Ron Collman (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) for 89.6, Malcolm Martin (Laboratory of Molecular Microbiology, NIAID, NIH, Bethesda, Md.) for ADA-8, and Michael Cho (Laboratory of Molecular Microbiology, NIAID, NIH, Bethesda, Md.) for DH125.

Single-round replication competent envelope-complemented viruses were generated by cotransfection of 293T cells with 5 μg each of backbone vector pNL4-3 Env(−) LUC(+) and one of the envelope-expressing vectors. Similarly, molecularly cloned HIV-1 viruses were generated by transfection of the appropriate plasmid into 293T cells. Virus collected in the culture supernatants was quantified by determination of RT activity.

Infections.

B lymphocytes collected at different stages of CD40-mediated proliferation were seeded at 5 × 104 cells per well of a 96-well culture plate with single-round competent luciferase viruses at a cell/virus (cpm of RT) ratio of 1:2. After 72 or 120 h in the case of cells infected at day 0, cell lysates were assayed for luciferase activity according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Agents used to block infection included anti-CD4 MAb RPA-T4 (Pharmingen), recombinant human stromal cell-derived factor 1β (SDF-1β; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, N.J.), and polypeptide ALX40-4C (N-α-acetyl-nona-d-arginine amide; American Peptide, Sunnyvale, Calif.). For full virus replication kinetics a cell/virus (cpm of RT) ratio of 1:1 was used for infections. After overnight incubation with virus, the cells were washed several times and replated at 5 × 104 cells per well of a 96-well culture plate. Virus replication was assessed by periodically measuring HIV-1 p24 antigen in the culture supernatant by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Coulter).

RESULTS

Induction of CD4 and CXCR4 on CD40-stimulated B lymphocytes.

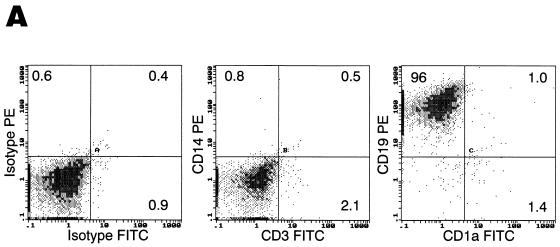

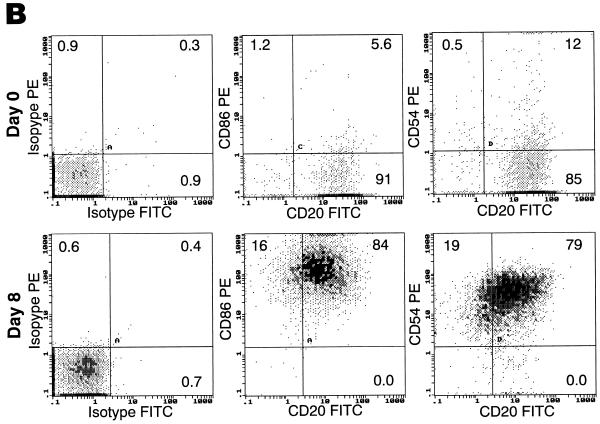

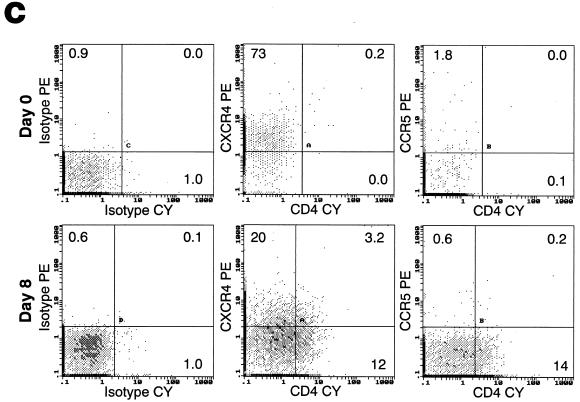

We have previously established that HIV-1 can productively infect CD40-activated B lymphocytes (31). In order to determine the mode of infection, we followed the modulation of potential HIV-1 receptors during CD40-mediated proliferation. Highly purified cultures of B lymphocytes from normal volunteers were generated from PBMCs after isolation and cultivation for several days in B-cell enriching medium containing IL-4 and soluble CD40L (Fig. 1A). As previously described (16), CD40 triggering upregulated activation markers HLA-DR and CD23 (data not shown), as well as costimulatory molecules CD80 (not shown), CD86 and CD54 (Fig. 1B). Expression of the HIV-1 receptor CD4 and major coreceptors CCR5 and CXCR4 was also evaluated in response to CD40-mediated proliferation. CD4 expression, while generally undetectable on freshly isolated B lymphocytes, was detected on approximately 15% of the cultured population by day 8 (Fig. 1C). This pattern of CD4 upregulation in IL-4/CD40L stimulatory conditions was also observed at the mRNA level, with little signal detected at the time of isolation, followed by a significant increase during the period of culture (Fig. 1D). The pattern of expression was somewhat reversed for CXCR4 (Fig. 1C). Although nearly 100% of B lymphocytes stained positive for CXCR4 at the time of isolation (Fig. 1C), levels dropped to undetectable during the very early stages of CD40-mediated proliferation (data not shown), followed by reexpression in approximately 23% of the population by day 8 of proliferation (Fig. 1C). Surface CCR5 expression remained undetectable at all time points (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Temporal modulation of cell surface markers on CD40-stimulated B lymphocytes. Cultures of B lymphocytes were analyzed for CD3, CD14, and CD1a contamination and CD19 purity at day 8 of proliferation (A), for costimulatory molecules CD86 and CD54 (B), and for HIV-1 receptors CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5 on CD20-gated cells immediately after isolation and at day 8 of proliferation (C). Percentages of cells within each quadrant are indicated. Profiles are representative of five different donors. (D) RT-PCR analysis of CD4 and control β-actin mRNA expression on freshly isolated B lymphocytes (B-d0), day 10 B-lymphocyte culture (B-d10), and CD8-depleted anti-CD3 stimulated day 3 PBMCs (PBL-d3).

Upregulation of CD4 and CXCR4 correlates with susceptibility of B lymphocytes to infection with luciferase viruses pseudotyped with CXCR4-dependent HIV-1 envelopes.

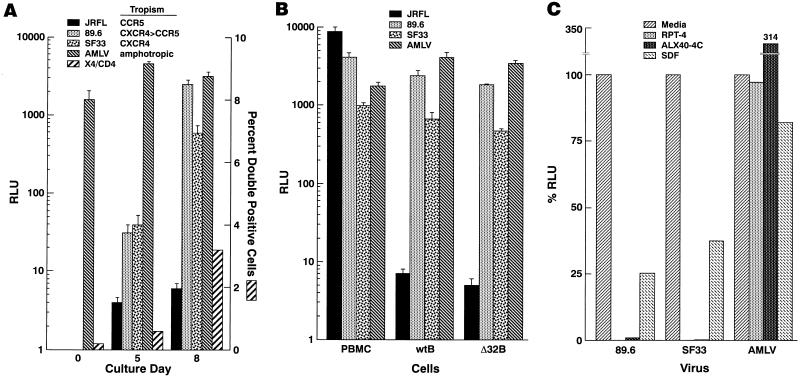

The appearance of a population of CD4/CXCR4 double-positive B lymphocytes led us to investigate whether this phenotype correlated with the capacity to support HIV-1 replication. To this end, we periodically evaluated the susceptibility of cells to infection with single-round competent HIV-1 luciferase-based viruses that were complemented with either HIV or amphotropic envelopes. In preliminary assays, the levels of luciferase activity observed with the amphotropic pseudotype reflected proliferative capacity, as measured by thymidine incorporation (data not shown). Cells challenged at the time of isolation were not infectable with HIV-1 envelope pseudotyped viruses and yet were infectable with amphotropic envelope-mediated virus (Fig. 2A). By day 5 of CD40-mediated proliferation, when the coexpression of HIV receptors CD4 and CXCR4 was still below 1%, the cells were highly infectable, with virus expressing the amphotropic murine leukemia virus (AMLV) envelope, and yet weakly infectable with T-tropic SF33 envelope complemented virus (Fig. 2A). However, as the population began to shift toward a significant level of CD4/CXCR4 double expression (Fig. 1C and 2A), significant increases in susceptibility to virus complemented with T-tropic and dual-tropic HIV-1 envelopes were also observed (Fig. 2A). Finally, and consistent with the absence of surface CCR5 over the course of the culture period, the B lymphocytes remained resistant to virus pseudotyped with the M-tropic envelope JRFL at all time points. In contrast, PBMCs stimulated for 3 days with anti-CD3 MAb and depleted of CD8+ T cells were found to be susceptible to all envelopes of the panel of luciferase virus pseudotypes, indicating that there was no intrinsic defect in the M-tropic complemented virus (Fig. 2B). Further evidence that CCR5 plays no role in the infection of B lymphocytes came from cells isolated from individuals homozygous for the CCR5Δ32 mutation. When cells were cultured in parallel conditions, demonstrating equivalent levels of AMLV-pseudotyped luciferase activities (Fig. 2B), there was no significant difference in susceptibility to HIV-1-pseudotyped viruses between B lymphocytes isolated from individuals wild-type for CCR5 and homozygous for CCR5Δ32 (Fig. 2B).

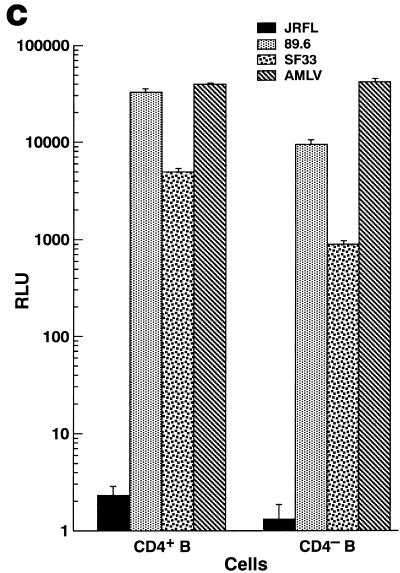

FIG. 2.

Appearance of CD4/CXCR4 double-positive CD40-stimulated B lymphocytes correlates with susceptibility to HIV-1 infection. (A) B lymphocytes taken at days 0, 5, and 8 of proliferation were infected with single-round competent HIV-1 luciferase viruses pseudotyped with the four different envelopes indicated. The percentage of cells coexpressing CD4 and CXCR4 on day of infection is shown. (B) Infection of day 10 B lymphocytes isolated from individuals wild-type for CCR5 (wtB) and homozygous for CCR5Δ32 (Δ32B), as well as day 3 CD8-depleted anti-CD3-stimulated PBMCs was carried out with the panel of four luciferase viruses. At 72 h postinfection, cells were lysed, and lysates were assayed for luciferase activity; values are reported as relative light units (RLU). In the case of day 0 B lymphocytes, the cells were lysed at 120 h postinfection. Each infection was done in triplicate; the data are the means of each triplicate, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations of the means. (C) Day 8 B lymphocytes were incubated for 30 min with either 1 μg of anti-CD4 MAb RPA-T4 per ml, 5 μg of SDF-1β per ml, or 10 μg of CXCR4 inhibitor ALX40-4C per ml prior to infection. RLU values were normalized to 100% for cells infected in the absence of inhibitors.

HIV-1 luciferase virus single-round infection is specifically inhibited by blockers of CD4 and CXCR4.

In order to directly identify the receptors responsible for HIV-1 infection of CD40-stimulated B lymphocytes, B cells were incubated with inhibitors of CD4 or CXCR4 prior to addition of the luciferase viruses. As shown in Fig. 2B, the anti-CD4 MAb RPA-T4 completely blocked infection with T-tropic and dual-tropic HIV-1 enveloped pseudotypes and yet had no effect on the amphotropic virus whose infectivity is CD4 independent. CXCR4 usage was verified with the chemical antagonist ALX40-4C, an arginine-based peptide that has been shown to bind CXCR4 with high affinity, block SDF-1-mediated activation, and potently inhibit CXCR4-using strains of HIV-1 (9). Similar to the blocking effect of the anti-CD4 MAb, the ALX40-4C peptide was found to essentially abrogate the infection with both T- and dual-tropic enveloped HIV-1 pseudotypes, while increasing the infectivity of the amphotropic virus. While the reason for this enhancing effect is not known, similar effects of post-entry HIV-1 enhancement after ligand-mediated activation of CXCR4 have recently been reported (22). This may explain why in the case of a virus such as AMLV that is not blocked at entry, postentry effects may be observed. On the other hand and in agreement with other studies (34, 37), we found that the natural ligand of CXCR4, SDF-1, blocked infection to lesser and more variable degrees (Fig. 2C). Nonetheless, these data strongly suggest that HIV-1 infection of CD40-activated B lymphocytes is mediated by CD4 and CXCR4.

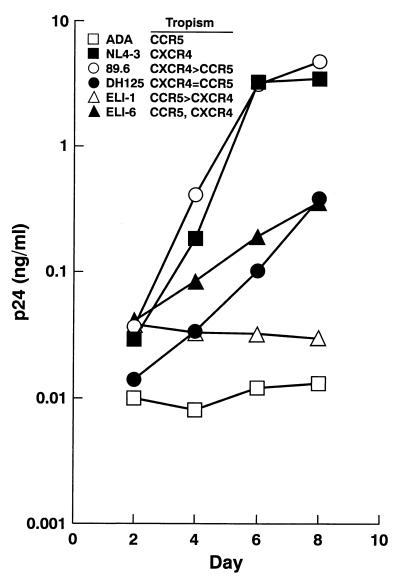

Productive infection with CXCR4-using strains of HIV-1 confirms the pattern of restricted tropism in B lymphocytes.

In order to further investigate the capacity of CD40-activated B lymphocytes to support HIV-1 infection, full virus replication kinetics were evaluated with a panel of molecular clones representative of the spectrum of cellular tropisms exhibited by HIV-1. The replication profiles observed (Fig. 3) confirmed the pattern of susceptibilities described with the single-round competent luciferase recombinant viruses. While the predominantly CCR5-dependent strains ADA and ELI-1 failed to establish productive infection, the dual-tropic strains 89.6 and DH125, as well as the T-tropic strains NL4/3 and ELI-6, succeeded in establishing robust infections in the CD40-stimulated B lymphocytes by day 6 postinfection. Furthermore, as indicated in the inset of Fig. 3, the differences in replication kinetics between the various molecular clones tested completely reflected the extent to which each strain was capable of using CXCR4.

FIG. 3.

Productive infection of B lymphocytes is restricted to CXCR4-using strains of HIV-1. Full virus replication kinetics were analyzed by infecting cells at day 10 of CD40-mediated proliferation with a panel of HIV-1 molecular clones representative of the scope of CCR5 and CXCR4 dependencies. Each infection was done in triplicate. Culture supernatants were collected periodically, and the triplicates were pooled and assayed for p24 antigen.

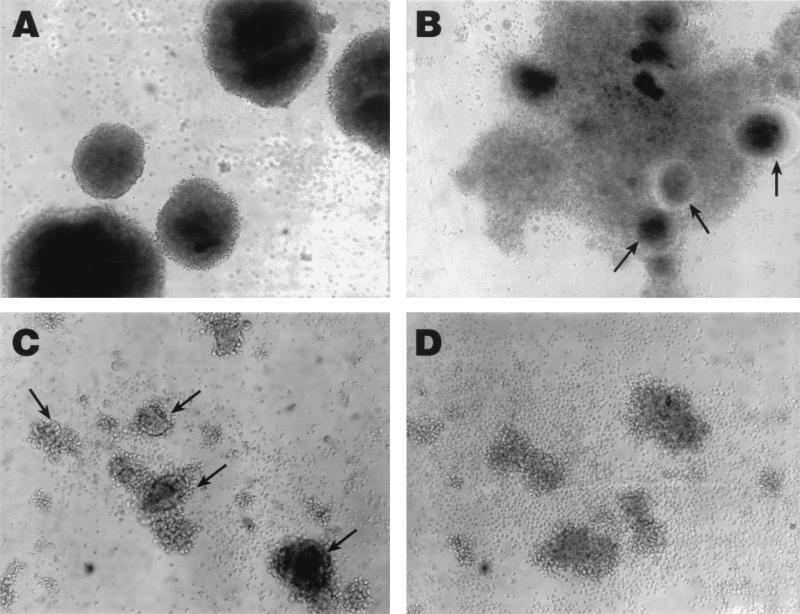

The replication of CXCR4-dependent HIV-1 strains in activated CD4 T lymphocytes is generally characterized by a rapid and highly cytopathic course. While replication of such strains in B lymphocytes demonstrated rapid kinetics, there was little evidence of cell death and syncytia formation (Fig. 4A). However, productive cycles of virus replication were taking place in these cells, as evidenced by the p24 levels in the culture supernatant (Fig. 3) and the rapid formation of large syncytia upon cocultivation of the infected B lymphocytes with SupT1 T cells (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Effect of culture conditions on syncytium formation in B lymphocytes infected with an NL4/3 strain of HIV-1. Day 8-infected B lymphocytes grown in IL-4 and CD40L conditions did not form syncytia (A) and yet readily induced syncytia in cocultured SupT1 cells (4 h postincubation) (B). In sorting conditions with B lymphocytes grown in the presence of IL-2, IL-10, and CD40L, syncytia were present at day 7 postinfection in the CD4+ enriched B-lymphocyte population (C) and yet absent in the CD4− enriched fraction (D).

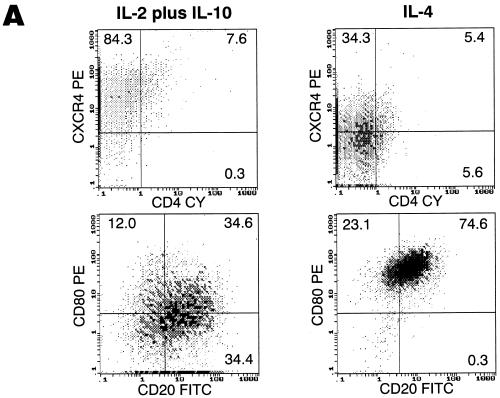

Replacement of IL-4 with IL-2 and IL-10 enhances CD4/CXCR4 expression on B cells and allows for isolation of a highly enriched target cell population for HIV-1.

While IL-4 was the first cytokine used to achieve long-term CD40-mediated proliferation of B lymphocytes (1), other cytokines, such as the combination of IL-10 and IL-2, have also been shown to be effective growth factors for B lymphocytes (12). Accordingly, this combination was evaluated for its effect on the modulation of CD4 and HIV coreceptor expression on cultured B lymphocytes. While not as effective as IL-4 for inducing cell proliferation and upregulation of costimulatory molecules such as CD80 (Fig. 5A), the IL-2–IL-10 combination proved to be more effective at enhancing the coexpression of CXCR4 and CD4 (Fig. 5A) and yet had little effect on CCR5 (data not shown). We also found that by starting from CD2-depleted PBMCs rather than from highly purified B lymphocytes isolated by magnetic bead depletion, the coexpression of CD4 and CXCR4 on the surface of the B lymphocytes was further enhanced. These conditions were consistently found to induce the expression of CXCR4 on nearly 100% of the B lymphocytes, a level very similar to that observed on freshly isolated cells (compare Fig. 1C and Fig. 5A). However, such conditions also favored the maintenance of low-level CD4+ T-cell contaminants in the culture, as evidenced by the occasional replication of JRFL-enveloped luciferase virus (data not shown). To resolve this problem, cells were grown in IL-4-containing medium for 7 days to favor proliferation and B-lymphocyte purification and then switched to IL-2–IL-10-containing medium and sorted on day 14. From a population of B lymphocytes expressing nearly 100% CXCR4 and 15% CD4, highly purified CD19+ CD4+ and CD19+ CD4− cell fractions were obtained (Fig. 5B).

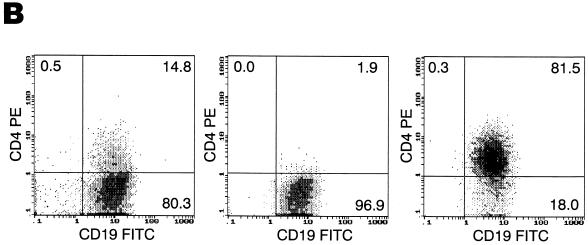

FIG. 5.

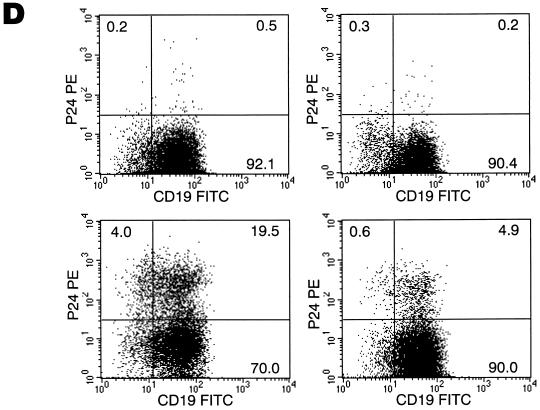

Sorting of a CD4+ population of IL-2–IL-10-conditioned B lymphocytes gives rise to a target cell population that is highly susceptible to HIV-1 infection. (A) Growth of B lymphocytes in IL-2–IL-10 conditions enhances CD4/CXCR4 coexpression, whereas IL-4 favors upregulation of costimulatory molecules. (B) IL-2–IL-10-grown B lymphocytes (left panel) were sorted into CD4− (middle panel) and CD4+ (right panel) fractions. (C) CD4+ and CD4− B lymphocyte fractions were infected with single-round competent HIV-1 luciferase viruses pseudotyped with various envelopes as described in Fig. 2. (D) Day 7 uninfected (top panels) and NL4/3-infected (bottom panels) CD4+-sorted (left panels) and CD4−-sorted (right panels) B-lymphocyte populations were stained for CD19 surface marker and intracellular p24 HIV antigen. The percentages of cells within each quadrant are indicated.

The sorted cells were challenged with luciferase viruses (Fig. 5C) to study the spectrum of susceptibility to HIV-1 and with the molecular clone NL4/3 (Fig. 5D) to analyze intracellular p24 expression in B-cell-gated cells. While both CD4+ and CD4− B-cell fractions displayed identical activities toward the AMLV-enveloped pseudotype, the CD4+ enriched population was three- to fivefold more effective at replicating luciferase viruses complemented with CXCR4-dependent envelopes 89.6 and SF33 than the CD4− population. In contrast, and consistent with the data presented in Fig. 2, no luciferase activity was detected with the JRFL envelope, indicating that there was no available CCR5 either from a contaminating population or from undetectable levels on the B cells. The higher levels of CXCR4-dependent HIV-enveloped luciferase virus activity in the CD4− fraction (Fig. 5C) compared to the nonsorted B lymphocytes grown in IL-4 conditions (Fig. 2A and B) may be due to a combination of effects, including a higher activation state in the sorted cells, as evidenced by the high luciferase activity detected with the AMLV-enveloped pseudotype and higher levels of surface CXCR4 (Fig. 5A).

Sorted B cells infected with the molecular clone NL4/3 were stained for intracellular p24 at day 6 postinfection. High-intensity staining was observed in 24% of the CD4+ enriched fraction compared to 5% staining in the CD4− fraction and less than 1% in uninfected cells of either fraction (Fig. 5D). Contrary to the observations made on either the IL-4- (Fig. 4A) or IL-2–IL-10-propagated (not shown) B lymphocytes and the CD4− sorted fraction (Fig. 4C), infection of the CD4+ sorted fraction with NL4/3 induced the formation of syncytia by day 7 (Fig. 4D). These data suggest that syncytia formation in B lymphocyte cultures may require a threshold level of CD4/CXCR4 expression that can only be attained by use of certain enrichment methods.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that primary B lymphocytes derived from peripheral blood can be infected with T-tropic and dual-tropic strains of HIV-1 in a process that is dependent on CD4 and CXCR4. We found that by using CD40L-based culture conditions to generate highly purified and activated B lymphocytes, a significant percentage of the population upregulated the HIV-1 receptors CD4 and CXCR4. The temporal modulation of these receptors coincided with susceptibility to CXCR4-dependent strains of HIV-1 and resistance to CCR5-dependent strains. Comparative analysis of the infectivity of luciferase viruses pseudotyped with HIV-1 versus amphotropic envelopes in the presence of specific inhibitors was used to directly establish that infection of the B lymphocytes was mediated through CD4 and CXCR4. The restricted pattern of susceptibility to HIV-1 infection observed with the envelope-pseudotyped luciferase viruses was confirmed with a panel of molecular clones representing the full spectrum of CCR5 and CXCR4 dependencies. Furthermore, contrary to the observation that in most target cells CXCR4-using strains of HIV-1 demonstrate syncytium-inducing properties (3), we find these same viral strains to be non-syncytium inducing when replicating in B-lymphocyte cultures. However, syncytia were observed in cultures that were highly enriched in cells expressing CD4, indicating that the absence of syncytium formation is not an inherent property of B cells but rather may simply be due to low frequency and intensity of CD4 expression normally observed in infected B-cell populations.

Several previous studies have demonstrated that B cells can be infected by HIV-1 in vitro. However, notwithstanding reports showing a mode of infection that is dependent on complement and serum immunoglobulins (14, 15), most studies have been conducted on B cell lines (8, 17, 33, 41). These are phenotypically different from the B lymphocytes that we describe in that transformation appears to induce the expression of CCR5 and, contrary to our findings, allows CCR5- and CXCR4-using strains to replicate with similar efficiencies (13). In agreement with a previous study on the expression of CCR5 on human leukocytes (40), we find that surface CCR5 is undetectable on freshly isolated B lymphocytes; furthermore, we find no evidence of upregulation of CCR5 during CD40-mediated proliferation. It is possible that in our culture system coreceptor expression was modulated by the presence of IL-4, a cytokine recently shown to downmodulate the expression of CCR5 and enhance the expression of CXCR4 (36). However, cultivation of the B lymphocytes in the presence of IL-2 and IL-10, cytokines that have been reported not to downregulate CCR5 (38), did not influence the pattern of coreceptor expression and did not alter the resistance to M-tropic strains of HIV-1.

Susceptibility of the CD40-triggered B lymphocytes to HIV-1 infection was lower relative to activated CD4+ T lymphocytes. However, levels of HIV-1 RT activities in B lymphocytes were always within the same log scale as the T lymphocytes and could be brought to similar levels by sorting for CD4 enrichment. Furthermore, the high level of amphotropic activity observed in the B lymphocytes suggests that once virus is internalized, the intracellular milieu is rich in LTR-responsive transcription factors. NF-κB is a likely candidate since its activity has been shown to increase with CD40 triggering of B cells (2, 20). Nonetheless, it cannot be excluded that the high level of amphotropic activity may reflect a higher density of unidentified AMLV receptors on B cells compared to T cells.

The present study demonstrates that one of the main B-cell-stimulatory pathways associated with cognate T-cell-dependent immune responses can also modulate the expression of HIV-1 surface receptors. Considering that HIV-1 infection is associated with chronic antigenic stimulation (11) and that CD40-CD40L interactions are associated with this process, it is likely that our ex vivo model is reflecting events that occur in vivo during the course of HIV-1 disease. In this regard, we have recently demonstrated, both by in situ hybridization on lymph node sections (25) and by quantitative analysis of proviral DNA in cells isolated from peripheral blood (26), that the B lymphocytes of certain HIV-infected individuals harbor virus. We are currently investigating whether our in vitro findings of CXCR4-restricted tropism also apply in vivo by determining the tropism of the proviral DNA isolated from the B-cell compartment of these individuals.

Finally, in light of our findings, it is possible to speculate on the role of B lymphocytes in HIV-1 pathogenesis. Clearly, even in a population of highly activated B lymphocytes, only a small percentage will coexpress CD4 and CXCR4. As such, the B-cell compartment cannot be considered a major contributor to plasma viral load, and functional defects due to direct infection can only be described as minor. However, the combination of low levels of virus replication and the absence of cytopathicity suggest that B lymphocytes may represent a reservoir for CXCR4-using strains of HIV-1, similar to macrophages in the case of CCR5-dependent strains of HIV-1. Furthermore, the restricted and short-lived nature of CD40-mediated activation (16) may favor the establishment of a pool of latently infected B lymphocytes that can occasionally be reactivated to release virus. The relevance of our CD40 model is underscored by the fact that the bulk of HIV replication and the establishment of latent reservoirs occur in lymphoid tissue (6, 10, 28), where proliferation of B lymphocytes is driven primarily by CD40-CD40L interactions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bradley Foltz and Catherine Watkins for their help in the flow cytometric analyses, Linda Ehler and Stephanie Mizell for recruitment of blood donors, Shawn Justement and Robert Jackson for technical assistance, Patricia Walsh for editorial assistance, and Mark Connors for helpful discussion.

This project was in part funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract number N01-56000.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banchereau J, de Paoli P, Valle A, Garcia E, Rousset F. Long-term human B cell lines dependent on interleukin-4 and antibody to CD40. Science. 1991;251:70–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1702555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berberich I, Shu G L, Clark E A. Cross-linking CD40 on B cells rapidly activates nuclear factor-kappa B. J Immunol. 1994;153:4357–4366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berson J F, Long D, Doranz B J, Rucker J, Jirik F R, Doms R W. A seven-transmembrane domain receptor involved in fusion and entry of T-cell-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains. J Virol. 1996;70:6288–6295. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6288-6295.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chirmule N, McCloskey T W, Hu R, Kalyanaraman V S, Pahwa S. HIV gp120 inhibits T cell activation by interfering with expression of costimulatory molecules CD40 ligand and CD80 (B71) J Immunol. 1995;155:917–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chougnet C, Thomas E, Landay A L, Kessler H A, Buchbinder S, Scheer S, Shearer G M. CD40 ligand and IFN-gamma synergistically restore IL-12 production in HIV-infected patients. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:646–656. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199802)28:02<646::AID-IMMU646>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun T W, Carruth L, Finzi D, Shen X, DiGiuseppe J A, Taylor H, Hermankova M, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Quinn T C, Kuo Y H, Brookmeyer R, Zeiger M A, Barditch-Crovo P, Siliciano R F. Quantification of latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1997;387:183–188. doi: 10.1038/387183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conge A M, Tarte K, Reynes J, Segondy M, Gerfaux J, Zembala M, Vendrell J P. Impairment of B-lymphocyte differentiation induced by dual triggering of the B-cell antigen receptor and CD40 in advanced HIV-1-disease. AIDS. 1998;12:1437–1449. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199812000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Rossi A, Roncella S, Calabro M L, D’Andrea E, Pasti M, Panozzo M, Mammano F, Ferrarini M, Chieco-Bianchi L. Infection of Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid B cells by the human immunodeficiency virus: evidence for a persistent and productive infection leading to B cell phenotypic changes. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:2041–2049. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doranz B J, Grovit-Ferbas K, Sharron M P, Mao S H, Goetz M B, Daar E S, Doms R W, O’Brien W A. A small-molecule inhibitor directed against the chemokine receptor CXCR4 prevents its use as an HIV-1 coreceptor. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1395–1400. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Embretson J, Zupancic M, Ribas J L, Burke A, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Haase A T. Massive covert infection of helper T lymphocytes and macrophages by HIV during the incubation period of AIDS. Nature. 1993;362:359–362. doi: 10.1038/362359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fauci A S. Host factors and the pathogenesis of HIV-induced disease. Nature. 1996;384:529–534. doi: 10.1038/384529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fluckiger A C, Garrone P, Durand I, Galizzi J P, Banchereau J. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) upregulates functional high affinity IL-2 receptors on normal and leukemic B lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1473–1481. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fritsch L, Marechal V, Schneider V, Barthet C, Rozenbaum W, Moisan-Coppey M, Coppey J, Nicolas J C. Production of HIV-1 by human B cells infected in vitro: characterization of an EBV genome-negative B cell line chronically synthesizing a low level of HIV-1 after infection. Virology. 1998;244:542–551. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gras G, Legendre C, Krzysiek R, Dormont D, Galanaud P, Richard Y. CD40/CD40L interactions and cytokines regulate HIV replication in B cells in vitro. Virology. 1996;220:309–319. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gras G, Richard Y, Roques P, Olivier R, Dormont D. Complement and virus-specific antibody-dependent infection of normal B lymphocytes by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Blood. 1993;81:1808–1818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grewal I S, Flavell R A. CD40 and CD154 in cell-mediated immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:111–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson E E, Yang J Y, Zhang R D, Bealer M. Altered HIV expression and EBV-induced transformation in coinfected PBLs and PBL subpopulations. Virology. 1991;182:186–198. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90662-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kornbluth R S, Kee K, Richman D D. CD40 ligand (CD154) stimulation of macrophages to produce HIV-1-suppressive beta-chemokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5205–5210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane H C, Masur H, Edgar L C, Whalen G, Rook A H, Fauci A S. Abnormalities of B-cell activation and immunoregulation in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:453–458. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198308253090803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lapointe R, Lemieux R, Darveau A. HIV-1 LTR activity in human CD40-activated B lymphocytes is dependent on NF-kappaB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;229:959–964. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lederman S, Cleary A M, Yellin M J, Frank D M, Karpusas M, Thomas D W, Chess L. The central role of the CD40-ligand and CD40 pathway in T-lymphocyte-mediated differentiation of B lymphocytes. Curr Opin Hematol. 1996;3:77–86. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199603010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marechal V, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Heard J M, Schwartz O. Opposite effects of SDF-1 on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Virol. 1999;73:3608–3615. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3608-3615.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moir S, Poulin L. Expression of HIV env gene in a human T cell line for a rapid and quantifiable cell fusion assay. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12:811–820. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moses A V, Williams S E, Strussenberg J G, Heneveld M L, Ruhl R A, Bakke A C, Bagby G C, Nelson J A. HIV-1 induction of CD40 on endothelial cells promotes the outgrowth of AIDS-associated B-cell lymphomas. Nat Med. 1997;3:1242–1249. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orenstein, J., and M. A. Polis. 1998. Unpublished data.

- 26.Ostrowski, M., A. Malaspina, S. Moir, and A. S. Fauci. 1998. Unpublished data.

- 27.Paganelli R, Scala E, Ansotegui I J, Ausiello C M, Halapi E, Fanales-Belasio E, D’Offizi G, Mezzaroma I, Pandolfi F, Fiorilli M, Cassone A, Aiuti F. CD8+ T lymphocytes provide helper activity for IgE synthesis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with hyper-IgE. J Exp Med. 1995;181:423–428. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pantaleo G, Graziosi C, Demarest J F, Butini L, Montroni M, Fox C H, Orenstein J M, Kotler D P, Fauci A S. HIV infection is active and progressive in lymphoid tissue during the clinically latent stage of disease. Nature. 1993;362:355–358. doi: 10.1038/362355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinchuk L M, Polacino P S, Agy M B, Klaus S J, Clark E A. The role of CD40 and CD80 accessory cell molecules in dendritic cell-dependent HIV-1 infection. Immunity. 1994;1:317–325. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pope M, Elmore D, Ho D, Marx P. Dendrite cell-T cell mixtures, isolated from the skin and mucosae of macaques, support the replication of SIV. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:819–827. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poulin L, Paquette N, Moir S, Lapointe R, Darveau A. Productive infection of normal CD40-activated human B lymphocytes by HIV-1. AIDS. 1994;8:1539–1544. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199411000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schnittman S M, Fauci A S. Human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: an update. Adv Intern Med. 1994;39:305–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tozzi V, Britton S, Ehrnst A, Lenkei R, Strannegard O. Persistent productive HIV infection in EBV-transformed B lymphocytes. J Med Virol. 1989;27:19–24. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890270105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trkola A, Paxton W A, Monard S P, Hoxie J A, Siani M A, Thompson D A, Wu L, Mackay C R, Horuk R, Moore J P. Genetic subtype-independent inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by CC and CXC chemokines. J Virol. 1998;72:396–404. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.396-404.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsunetsugu-Yokota Y, Yasuda S, Sugimoto A, Yagi T, Azuma M, Yagita H, Akagawa K, Takemori T. Efficient virus transmission from dendritic cells to CD4+ T cells in response to antigen depends on close contact through adhesion molecules. Virology. 1997;239:259–268. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valentin A, Lu W, Rosati M, Schneider R, Albert J, Karlsson A, Pavlakis G N. Dual effect of interleukin 4 on HIV-1 expression: implications for viral phenotypic switch and disease progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8886–8891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verani A, Pesenti E, Polo S, Tresoldi E, Scarlatti G, Lusso P, Siccardi A G, Vercelli D. CXCR4 is a functional coreceptor for infection of human macrophages by CXCR4-dependent primary HIV-1 isolates. J Immunol. 1998;161:2084–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J, Roderiquez G, Oravecz T, Norcross M A. Cytokine regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry and replication in human monocytes/macrophages through modulation of CCR5 expression. J Virol. 1998;72:7642–7647. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7642-7647.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolthers K C, Otto S A, Lens S M, Van Lier R A, Miedema F, Meyaard L. Functional B cell abnormalities in HIV type 1 infection: role of CD40L and CD70. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:1023–1029. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu L, Paxton W A, Kassam N, Ruffing N, Rottman J B, Sullivan N, Choe H, Sodroski J, Newman W, Koup R A, Mackay C R. CCR5 levels and expression pattern correlate with infectability by macrophage-tropic HIV-1, in vitro. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1681–1691. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang R D, Henderson E E. CD4 mRNA expression in CD19-positive B cells and its suppression by the Epstein-Barr virus. Virology. 1994;198:709–713. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]