Abstract

Despite therapeutic advancements, cervical cancer caused by high-risk subtypes of the human papillomavirus (HPV) remains a leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women worldwide. This study aimed to discover potential drug candidates from the Asian medicinal plant Andrographis paniculata, demonstrating efficacy against the E6 protein of high-risk HPV-16 subtype through an in-silico computational approach. The 3D structures of 32 compounds (selected from 42) derived from A. paniculata, exhibiting higher binding affinity, were obtained from the PubChem database. These structures underwent subsequent analysis and screening based on criteria including binding energy, molecular docking, drug likeness and toxicity prediction using computational techniques. Considering the spectrometry, pharmacokinetic properties, docking results, drug likeliness, and toxicological effects, five compounds—stigmasterol, 1H-Indole-3-carboxylic acid, 5-methoxy-, methyl ester (AP7), andrographolide, apigenin and wogonin—were selected as the potential inhibitors against the E6 protein of HPV-16. We also performed 200 ns molecular dynamics simulations of the compounds to analyze their stability and interactions as protein–ligand complexes using imiquimod (CID-57469) as a control. Screened compounds showed favorable characteristics, including stable root mean square deviation values, minimal root mean square fluctuations and consistent radius of gyration values. Intermolecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts, were sustained throughout the simulations. The compounds displayed potential affinity, as indicated by negative binding free energy values. Overall, findings of this study suggest that the selected compounds have the potential to act as inhibitors against the E6 protein of HPV-16, offering promising prospects for the treatment and management of CC.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, High-risk HPV-16, E6 inhibitors, A. paniculata, Phytocompounds

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Oncology

Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC), ranking fourth in both incidence and mortality rates, remains a leading contributor to morbidity and cancer-related deaths globally1. In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported approximately 660,000 new cases of CC, resulting in roughly 350,000 deaths (WHO 2022). From 2022 to 2030, the estimated yearly count of new CC cases worldwide is expected to escalate from 660,000 to 700,000, while the projected annual deaths are anticipated to climb from 350,000 to 400,0002. Despite being entirely preventable, CC remains the primary cause of cancer-related deaths among women in 36 low-income and middle-income countries3,4. In Bangladesh, CC ranks as the second most prevalent cancer among females. Annually, this disease leads to 8,086 new cases, resulting in 5,214 deaths in Bangladesh5,6.

Cancer of the cervix is a malignancy that originates in the cells of the uterine cervix and may later spread to other regions of the female reproductive system. The cells affected by cervical cancer are those found in the tissues of the cervix, particularly the glandular and squamous cells7. It can be transmitted through sexual activities and infects various organs of the body, including squamous epithelia like the skin, upper respiratory tract, and mucous membranes of the anogenital region. Persistent infection with high-risk subtypes of the human papillomavirus (HPV) is the primary etiological agent for the development of CC, alongside other contributing factors involved in the pathogenesis3,8. HPV possesses a double-stranded DNA structure, the capability to integrate into the host genome, and encodes several viral proteins that play a role in its replication and pathogenicity. Since the identification of the HPV in the early 1980s, the majority of CC cases have been linked to HPV infection9. However, not all instances of HPV infections in women lead to CC. High-risk HPV genotypes such as HPV-16 and HPV-18 can instigate the transformation of normal cells into precancerous lesions, which can subsequently progress into invasive lesions9,10. These two genotypes types are responsible for 70% of CCs in women under the age of 45 globally9. Sexual contact is causing the transmission of the infection which gives rise to squamous intraepithelial lesions. However, genetic modifications in the viral genome like loss of heterozygosity, mutation, and amplification, and epigenetic mechanisms, contribute to CC. Additionally, local microbiota and environmental factors like smoking, diet, oxidative stress and hormonal dysregulation are associated with CC development and progression8. The interaction between tumor suppressor proteins, specifically p53 and pRB (retinoblastoma), and viral oncoproteins (E6 and E7) determine the development of CC. HPV-encoded E6 and E7 proteins are crucial oncogenes driving HPV-related carcinogenesis by regulating key signaling pathways, advancing malignancy11,12. HPV E6 and E7 proteins possess the ability to modulate various tumor-associated signaling pathways, such as Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/Akt, NF-kB, among others12. HPV-16 E6 has the capability to facilitate HPV carcinogenesis by interacting with IKK, thereby influencing its catalytic activity and enhancing activation of the NF-kB pathway. Consequently, this disturbance in the immune response occurs12. This modulation stimulates tumor cell growth and infiltration, induces apoptosis, enhances glycolysis, regulates tumor inflammation and immunity, thereby promoting tumor progression13. Hence, understanding the molecular mechanisms through which E6 and E7 influence tumor-associated signaling pathways could be of paramount significance in diagnosing and treating HPV-associated tumors. Dysregulation in various cellular activities such as cellular adhesion, cellular control, host cell immunomodulation and genotoxicity contribute to the severity of the disease14. The application of target non-specific chemotherapeutic agents and surgical techniques are used to cure the infections, but these are expensive and invasive treatments which are not available to millions of patients14,15. At present, there is no targeted treatment available for HPV. Traditional cancer therapies such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy frequently generate side effects due to off-target cytotoxicity, and can damage other healthy tissues16. Therefore, there is a demand for next-generation cancer drugs along with more precise drug delivery systems to enhance cancer treatment efficacy.

In recent years, plants have gained momentum in research for the alleviation of major human diseases such as cancer and HIV/AIDS17,18. Herbal plants have been used in the production of anti-HIV recombinant proteins or antiretroviral drugs19,20. In traditional Asian medicines “Androghraphis paniculata” have been proved useful for centuries. It is an herb which is commonly found in Southeast Asian countries and known as kalomegh or ‘king of bitters’ belonging to the family of Acanthaceae17,19. Whole plant extracts are found to have anticancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic, immunostimulatory, antiviral, hypoglycemic, hypotensive and antithrombotic activities17. A. paniculata is such a drug used widely for its antiviral and anticancer effects in HPV and CC19. The aim of this study was to identify potential drug candidates from A. paniculata effective against the E6 protein of HPV-16 using in-silico analysis. The results of this study suggest that the active compounds present in A. paniculata may possess the ability to inhibit the E6 protein, through interaction with E6AP (E6 associated protein) and E3 ubiquitin ligase. This inhibition could potentially counteract the suppression of tumor cell apoptosis in high-risk HPV. By this way, our ultimate motive is to establish a natural anticancer drug with high efficiency and less side effects. Our observations are based on the thermodynamic data (molecular formula, molecular weight, internal energy, enthalpy, Gibbs free energy and dipole moment), chemical stability data (Energy and gap of HOMO–LUMO, hardness, softness, chemical potential, electronegativity and electrophilicity), geometrical data (FT-IR, Raman, UV–Vis), selected vibrational frequencies, electronic absorption spectra, toxicity prediction and ADMET analysis of A. paniculata with its active constituents. Moreover, various computational methods such as molecular docking, clarification of protein–ligand interactions, analysis of non-bonding interactions, and molecular dynamics simulation (MDS) are routinely employed to discover and validate potential drug candidates against different types of cancer21–23. The active constituents of A. paniculata showed potential binding affinity with the E6 protein found in HPV-positive CC, mitigating its carcinogenic impact. With their notable anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and anticancer properties, A. paniculata emerges as a compelling candidate for developing therapeutics targeting HPV-16, thereby facilitating cell apoptosis and addressing the severity of CC, though wet lab validation remains essential.

Results

Thermodynamic analysis

This study focused on predicting potential drug candidates effective against the E6 protein of HPV-16 using in-silico computational approaches. We studied the thermodynamic properties of five phytocompounds such as stigmasterol, AP7, andrographolide, apigenin and wogonin available in A. paniculata (Table S1). All the compounds studied demonstrated higher negative free energy values than imiquimod (control drug). Imiquimod (Control 1) exhibited a free energy value of − 761.9551 Hartree, whereas stigmasterol, AP7, andrographolide, apigenin, and wogonin showed values of − 1208.6234 Hartree, − 1154.6738 Hartree, − 1155.8787 Hartree, − 953.5894 Hartree, and − 992.7466 Hartree, respectively (Fig. 1a, Table 1). The majority of the compounds we investigated exhibit higher dipole moments compared to both control drugs. Andrographolide, apigenin and wogonin displayed elevated dipole moments of 6.0839 Debye, 3.8546 Debye, and 4.3641 Debye, respectively, suggesting fine solubility, permeability, and oral bioavailability of a drug molecule compared to imiquimod (3.9172 Debye) and podophyllotoxin (4.0853 Debye) (Fig. 1b and Table 1). The calculated HOMO–LUMO energy gap of selected compounds of A. paniculata ranged between 3.5048 eV and 6.8572 eV (Fig. 1c). Importantly, AP7, andrographolide and apigenin possessed HOMO–LUMO energy gaps of 3.9630 eV, 5.4660 eV, and 4.1574 eV, respectively. The calculated HOMO–LUMO energy gaps for the control drugs imiquimod (control 1) and podophyllotoxin (control 2) were found to be 4.7376 eV and 5.2945 eV, respectively, which are higher than those for all compounds except stigmasterol and andrographolide (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

(a) Free energy, (b) dipole moment and (c) HOMO–LUMO energy gap of selected compounds of A. paniculata. Control 1 = imiquimod, Control 2 = podophyllotoxin, AP7 = 1H-Indole-3-carboxylic acid, 5-methoxy-, methyl ester.

Table 1.

Molecular formula (MF), molecular weight (MW), energies (Hartree), and dipole moment (Debye) of phytoconstituents of A. paniculata.

| Name | MF | MW | Internal energy | Enthalpy | Gibbs free energy | Dipole moment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigmasterol | C29H48O | 412.69 | − 1208.5294 | − 1208.5284 | − 1208.6234 | 1.3363 |

| *AP7 | C20H28O5 | 348.43 | − 1154.5945 | − 1154.5936 | − 1154.6738 | 2.4912 |

| Andrographolide | C20H30O5 | 350.45 | − 1155.7994 | − 1155.7984 | − 1155.8787 | 6.0839 |

| Apigenin | C15H10O5 | 270.24 | − 953.5305 | − 953.5295 | − 953.5894 | 3.8546 |

| Wogonin | C16H12O5 | 284.26 | − 992.7885 | − 992.7876 | − 992.7466 | 4.3641 |

| Imiquimod (Control 1) | C14H16N4 | 240.3 | − 761.8974 | − 761.8974 | − 761.9551 | 3.9172 |

| Podophyllotoxin (Control 2) | C22H22O8 | 414.4 | − 1452.8988 | − 1452.8978 | − 1452.9847 | 4.0853 |

*AP7 = 1H-Indole-3-carboxylic acid, 5-methoxy-, methyl ester.

Lead molecular orbital analysis

The outcome of the analysis indicated that the HOMO energy of andrographolide is lower than the other drugs, while stigmasterol had the largest gap energy. The energy gap (Egap) of the studied compounds was in the following order: wogonin < AP7 < apigenin < imiquimod (Std.1) < podophyllotoxin (Std.2) < andrographolide < stigmasterol (Table 2). Lower HOMO–LUMO gap indicates the less stability of the molecule as the electronic transition is more likely to happen upon excitation. Thus, compounds with less HOMO–LUMO band gap are more reactive in nature. Through in our analysis, we have found three of our studied compounds namely Ap7, Apigenin, and Wogonin have lower HOMO–LUMO band gap compare to the control that their higher reactivity while interacting with target compounds24. Also, the higher the HOMO value of a molecule (Table 2), the better the molecule to donate an electron to a target receptor25. Another important indication was all studied compounds have lower HOMO values than control compounds. That suggested the metabolic stability of studied compounds as lower HOMO values may be less prone to metabolic transformations involving oxidation. This can lead to a longer half-life in the body and potentially prolonged therapeutic effects26,27. The density of states (DOS) for the five chosen compounds is illustrated in Fig. 2. Arrows within the figure highlight the band gap of each molecule, color-coded to facilitate visual comparison. Consequently, wogonin displayed high chemical reactivity, whereas stigmasterol exhibited low reactivity (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Energy (eV) of HOMO–LUMO, gap, hardness (η), softness (S), chemical potential (µ), electronegativity (χ), and electrophilicity (ω) of A. paniculata.

| Drugs | EHOMO | ELUMO | Egap | η | S | µ | χ | ω |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigmasterol | − 6.1696 | 0.6876 | 6.8572 | 3.4286 | 0.2916 | − 2.7410 | 2.7410 | 1.0956 |

| *AP7 | − 5.8041 | − 1.8411 | 3.9630 | 1.9815 | 0.5046 | − 3.8226 | 3.8226 | 3.6871 |

| Andrographolide | − 6.7340 | − 1.2680 | 5.4660 | 2.7330 | 0.3658 | − 4.0010 | 4.0010 | 2.9286 |

| Apigenin | − 5.8948 | − 1.7374 | 4.1574 | 2.0787 | 0.4810 | − 3.8161 | 3.8161 | 3.5028 |

| Wogonin | − 5.3380 | − 1.8332 | 3.5048 | 1.7524 | 0.5706 | − 3.5856 | 3.5856 | 3.6682 |

| Imiquimod (Control 1) | − 5.3272 | − 0.5896 | 4.7376 | 2.3688 | 0.2111 | − 2.9584 | 2.9584 | 1.8474 |

| Podophyllotoxin (Control 2) | − 5.6942 | − 0.3997 | 5.2945 | 2.6473 | 0.1889 | − 3.0469 | 3.0469 | 1.7534 |

*AP7 = 1H-Indole-3-carboxylic acid, 5-methoxy-, methyl ester.

Figure 2.

Density of state (DOS) plot of HOMO–LUMO and energy gap of five selected compounds of A. paniculata. Here (a) stigmasterol, (b) AP7 (1H-Indole-3-carboxylic acid, 5-methoxy-, methyl ester), (c) andrographolide, (d) apigenin and (e) wogonin. Green and red dots show HOMO and LUMO orbitals.

Molecular electrostatic potentials of the compounds

In molecular recognition, the MEP map serves as a valuable visual tool for analyzing a molecule's relative polarity. The MEP map of the five selected compounds is presented in Fig. 3. Various colors on the map denote distinct electrostatic potential zones. The MEP map of the selected compounds from A. paniculata revealed that oxygen atoms exhibited the most negative potential, while hydrogen atoms exhibited the highest positive potential. The spectrum of positive electrostatic potential ranged from + 4.867 to + 7.055 a.u., while the negative electrostatic potential extended from − 4.867 to − 7.055 a.u. (Fig. 3). Notably, wogonin showed the highest positive potential at + 7.055 a.u. and the highest negative potential at − 7.055 a.u. Conversely, stigmasterol demonstrates the lowest positive potential at + 4.867 a.u. and the lowest negative potential at − 4.867 a.u. Additionally, AP7, andrographolide and apigenin exhibited positive electrostatic potentials of (+ 6.640 a.u.), (+ 6.839 a.u.), and (+ 7.600 a.u.) respectively, as well as negative electrostatic potentials of (− 6.640 a.u.), (− 6.839 a.u.), and (− 7.600 a.u.) respectively (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) map of selected five compounds of A. paniculata. Different colors are used to specify the charge distribution such as- blue, red, and green colors which are used to determine the positive charge, negative charge, and neutral charge, respectively. Short electron density and poor interaction are identified on blue region, but red region contains high electron density and potential interaction.

Vibrational frequencies analysis

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is a method to analyze unknown substances by studying their molecular vibrations. The vibrational frequency values were multiplied by a scaling factor 0.9627 for their accuracy in agreement with the experimental values compared with standard sources (Fig. S1, Table S2). The C=H vibrations observed within the studied compounds varied between 2928 and 3175 cm−1, corresponding well with the experimental range of 2700–3300 cm−1, thereby verifying the existence of C=H bonds within their structures for various functional groups. The stretching range of C=C bonds ranged between 1545 and 1677 cm-1 which aligned with its experimental vibrational range of alkenes and aromatic compounds 1450–1680 cm−1 confirming the presence of C=C bond. The C=O stretching frequencies ranged from 1604 to1793 cm−1, confirming their presence. These values deviated slightly from the experimental range of 1650 to 1780 cm−1. Similarly, the O=H vibrations within the current functional groups were detected within the range of 3666–3686 cm−1, slightly deviating from the experimental range of 3200–3650 cm−1, probably due to scaling. This observation confirms the presence of various functional groups containing O=H bonds (Fig. S1, Table S1).

UV–visible spectral analysis

To comprehend the electronic transitions occurring within the molecules, we conducted time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) calculations for the five chosen compounds. The maximum absorbance (λmax) values, excitation energies, oscillator strengths (f), and transition assignments for all molecules were computed (Fig. S2, Table S3). The highest peak intensity was observed for AP7 at 2182.55 nm at S0 → S1 excited state with the configurations (0.46137) H-2 → L, (0.63400) H-1 → L, (− 0.32373) H-1←L with excitation energy 0.5681 eV. On the other hand, stigmasterol showed absorption band for S0 → S1 transition at 294.82 nm having excitation energy 4.2054 eV for configuration conformation (0.70652) H → L. Andrographolide, apigenin and wogonin displayed band for the same transition state at wavelengths 1380.57 nm, 350.58 nm, and 484.88 nm with excitation energies 0.8981 eV, 3.5365 eV, and 2.5570 eV, respectively. The control drugs imiquimod and podophyllotoxin exhibited peak intensities at 496.89 nm and 657.17 nm, respectively, corresponding to excitation energies of 2.4952 eV and 1.8866 eV (Fig. S2, Table S2).

Molecular docking of the selected compounds against drug target

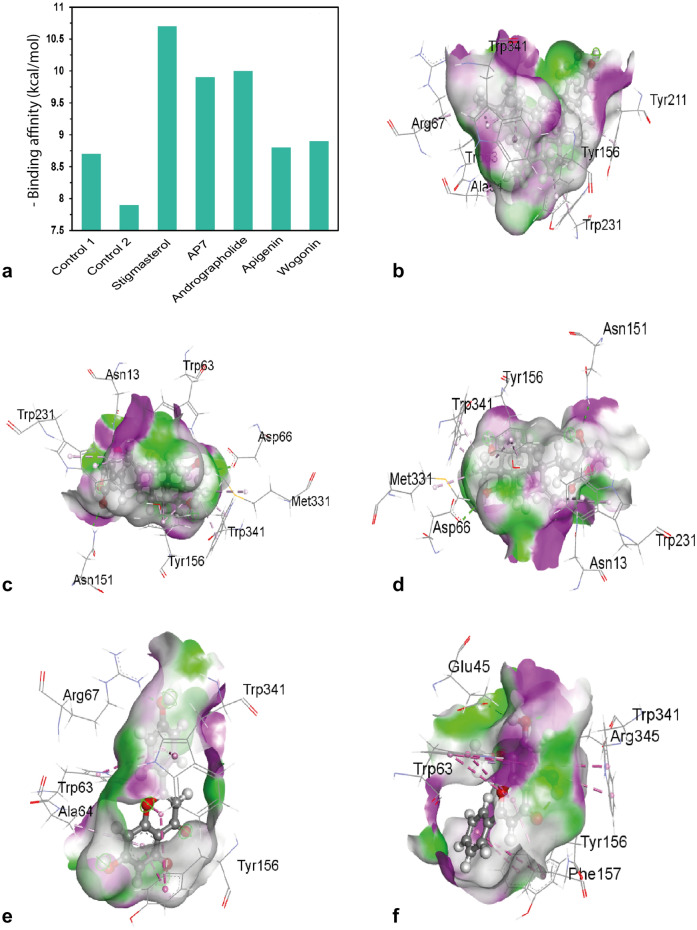

Using the PyRx in built AutoDock Vina wizard, we performed molecular docking between 42 phytochemicals and the target protein. After assessing binding scores and conducting structural analysis, the top 12% of the 42 phytochemical compounds— (a total of 5 compounds) were selected for further evaluation. These compounds revealed a superior binding score compared to control drugs imiquimod (control 1) and podophyllotoxin (control 2). In this study, imiquimod and podophyllotoxin were selected as control ligands due to their demonstrated inhibitory effects against the E6 (4xr8) protein, exhibiting binding affinities of − 8.7 kcal/mol and − 7.9 kcal/mol, respectively. The five selected compounds with the highest binding affinity, along with the structural analysis of imiquimod and podophyllotoxin (control drugs), are shown in Fig. 4a and Table S3.

Figure 4.

(a) Binding affinity of the selected compounds of A. paniculata and control drugs. (b–f) docked conformer, interactions and hydrogen bond surface of selected compounds of A. paniculata against E6 (4xr8) protein. Here (b) stigmasterol, (c) AP7 (1H-Indole-3-carboxylic acid, 5-methoxy-, methyl ester), (d) andrographolide, (e) apigenin and (f) wogonin.

Clarification of protein–ligands interactivity

The investigated five compounds and the target protein (E6) exhibited various non-covalent interactions, including halogen bond, hydrogen bond, and hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 4b–f). Stigmasterol exhibited two alkyl bonds at the positions of ALA64 (3.8 Å) and ARG67 (4.5 Å). There were many pi-alkyl bonds present in the following distances: TRP63(4.7 Å), TRP63(5.0 Å), TRP63(5.2 Å), TYR156(4.0 Å), TYR211(4.8 Å), TRP231(5.1 Å), TRP341(3.6 Å), TRP341(4.8 Å), TRP341(4.0 Å) (Fig. 4b). During the interaction of the molecule AP7, four hydrogen bonds conforming to traditional patterns were observed at specific positions. These positions were ASN13 (1.88 Å), TRP63 (1.95 Å), ASN151 (2.27 Å), and ASP66 (2.25 Å). Additionally, alkyl and a substantial number of pi-alkyl bonds were detected at positions MET331, TYR156, TYR156, TRP231, and TRP341 (Fig. 4c). Andrographolide compound exhibited the formation of three conventional hydrogen bonds with ASN13(2.01 Å), ASN151(2.33 Å), and ASP66 (2.44 Å) (Fig. 4d). Moreover, it formed alkyl and a substantial amount of pi-alkyl bonds with MET331, TYR156, TRP231, and TRP341. A single conventional hydrogen bond was identified between ARG67 and the target protein (E6), with a bond length of 2.15 Å (Fig. 4d). Apigenin showed hydrophobic interactions like pi-alkyl bonding with ALA64, Pi-Pi stacked bonding with TYR156, and Pi-Pi T-shaped bonding with TRP63 and TRP341 (Fig. 4e, Table S3). For wogonin, two regular hydrogen bonds were noted with ARG345 (2.53 Å) and GLU45 (2.08 Å). The target protein exhibited numerous hydrophobic interactions, including Pi-Pi stacking with TYR156, Pi-Pi T-shaped with TRP63, PHE157, and TRP341. Furthermore, it formed a pi-alkyl bond with TRP63 (4.78 Å) (Fig. 4f, Table S3).

Drug likeness and ADMET analysis

The drug likeness and ADMET characteristics of studied compounds along with controls is shown in Table 3. The Lipinski "rule of 5"—molecular weight (MW) < 500 daltons (Da), octanol–water partition coefficient (LOGPo/w) < 5, hydrogen bond donors < 5, hydrogen bond acceptors < 10, and molar refractivity should typically be between 40 and 130 were taken into consideration when analyzing the drug-likeness characteristics of each compound. This analysis demonstrates that every compound adheres to Lipinski's recommendations. These substances had a lower molecular weight than the controls (imiquimod and podophyllotoxin). Additional physiochemical characteristics of the chosen compounds—such as rotable bonds, heavy atoms, aromatic heavy atoms, H-bond acceptor, and H-bond donor— (shown in Table 3), suggested that these compounds have had the potential to be potential drug candidates. The lipophilicity values (LOGP) for the control drugs (imiquimod and podophyllotoxin) were 2.13 and 2.83, respectively, while for stigmasterol, AP7, andrographolide, apigenin and wogonin the values were 5.01, 2.65, 2.45, 1.89, and 2.55, respectively. In this investigation, all compounds except andrographolide demonstrated higher solubility compared to imiquimod. Wogonin, apigenin and stigmasterol exhibited greater solubility than podophyllotoxin. Apart from stigmasterol, the remaining four compounds showed high gastrointestinal (GI) absorption similar to the controls (imiquimod and podophyllotoxin). The selected compounds had synthetic accessibility values of 6.21, 5.54, 5.06, 2.96, and 3.15, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Drug likeness and ADMET analysis of studied compounds of A. paniculata.

| Name | M. W. (g/mol) | Heavy atoms | A. heavy atom | Rotatable bond | H-bond acceptors | H- bond donors | Log p/W | Logs (ESOL) | GI absorption | Lipinski | Synthetic accessibility | Molar refractivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigmasterol | 412.69 | 30 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5.01 | − 7.46 | Low | Yes | 6.21 | 132.75 |

| *AP7 | 348.43 | 25 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2.65 | − 3.53 | High | Yes | 5.54 | 95.15 |

| Andrographolide | 350.45 | 25 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2.45 | − 3.18 | High | Yes | 5.06 | 95.21 |

| Apigenin | 270.24 | 20 | 16 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1.89 | − 3.94 | High | Yes | 2.96 | 73.99 |

| Wogonin | 284.26 | 21 | 16 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2.55 | − 4.23 | High | Yes | 3.15 | 78.46 |

| Imiquimod (Control 1) | 240.30 | 18 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3.13 | − 3.38 | High | Yes | 2.20 | 75.12 |

| Podophyllotoxin (Control 2) | 414.40 | 30 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2.83 | − 3.71 | High | Yes | 4.64 | 103.85 |

*AP7 = 1H-Indole-3-carboxylic acid, 5-methoxy-, methyl ester, M.W. = Molecular weight, A. heavy atom = aromatic heavy atom, H-bond = Hydrogen bond, GI = Gastrointestinal.

Toxicity prediction

To assess the toxicological impacts of the screened compounds, Protox II was employed. With the exception of imiquimod (control 1), all compounds were determined to be free from hepatotoxic and mutagenic effects. Moreover, none exhibited carcinogenic properties apart from podophyllotoxin (control 2). Wogonin and apigenin were noted for their lack of immunotoxicity, presenting an added advantage over the other tested compounds. No cytotoxicity was observed among the screened compounds.

Molecular dynamic simulation trajectories of the compounds

Based on the drug spectrochemical, likeliness and pharmacokinetics properties, finally five compounds such as stigmasterol (CID-5280794), andrographolide (CID- 5,318,517), wogonin (CID-5281703), AP7 (1H-Indole-3-carboxylic acid, 5-methoxy-, methyl ester; CID-15411809), apigenin (CID-5280443) and a control drug (imiquimod; CID-57469) were selected for further studies using molecular dynamics simulations (MDS). The conformational stability and several intramolecular interaction parameters of a protein–ligand complex are studied in MD simulation. In this study, a 200 ns MD simulation was conducted to understand the conformational changes and rearrangements of the protein when bound to the specific ligand. Initially, the terminal snapshots from the 200 ns MD simulations trajectories were used to investigate intermolecular behavior. The average variation in the RMSD of the protein–ligand interaction falls within an acceptable range, with a range of 2–5 Å. The standard deviation, represented by RMSD, ranged from 3 to 5 Å across all binding compounds, except for CID-5280443 (apigenin) and CID-5280794 (stigmasterol), which exhibited some fluctuations. The minimal fluctuation in the RMSD value of the compounds, which remained within a narrow range and fell outside the acceptable limits, suggests that the protein–ligand complex structure illustrated in Fig. 5a maintains conformational stability. Besides, the RMSD of five compounds (ligands) was analyzed independently to observe their fluctuations during 200 ns simulation. Although the RMSD values of the selected compounds were within an acceptable range, CID-15411809 (AP7), CID-5318517 (andrographolide), and CID-5280443 (apigenin) had RMSD values of less than 1.0 (Fig. S3), indicating a consistent result when the ligands formed complexes with proteins (Fig. 5a). It is noteworthy that, based on the initial molecular screening, the ligand compounds bound perfectly to the binding cleft of the E6 protein (Fig. S4a). Throughout the MD simulation, stable interactions were observed between the studied compounds and the amino acids located around the pocket regions. A cartoon representation of the ligand–protein interactions is shown in Fig. S4b–f. Potential covalent interactions were observed between the ligands and the binding pocket residues, except for stigmasterol (CID-5280794), which exhibited non-covalent interactions throughout the 200 ns trajectories. The RMSF analysis was conducted on the compounds bound to the targeted protein model to examine alterations in the protein structure due to the binding of specific ligands to particular residue sites. As a result, the RMSF information associated with the six examined ligands substances, there is a minimal fluctuations possibility regarding a particular atom's movement in the simulated atmosphere except CID-5280443 (Fig. 5b). Alpha helices and beta strands, which are among the most rigid secondary structural elements, were shown to have a minimum observation rate between 80 and 400 amino acid residues. The most significant variation occurred at the beginning and end of the protein, where the N- and C-terminal subdomains are located. A higher radius of gyration (Rg) suggests the complex's tendency to be dynamic, while a lower Rg indicates its more tightly packed structure. Figure 6a illustrates that all six complexes exhibited stable Rg values with minimal deviations, suggesting a high level of rigidity within the complexes. The Rg readings for the substances CID-5318517 (andrographolide), CID-5281703 (wogonin), CID-5280794 (stigmasterol), CID-15411809 (AP7), CID-5280443 (apigenin) and control drug (CID-57469; imiquimod) were observed to be 4.0, 3.4, 5.3, 4.0, 3.5, and 4 Å, respectively (Fig. 6a). This indicates that the binding region of the protein remains relatively unchanged upon attachment of the selected ligand substances. The verification of structural identity and the functioning of biological macromolecules are regulated by the concentration of SASA. In this study, the SASA for the selected compounds ranged from 30 to 590 Å2, showing standard exposure of the selected compound with an amino acid residue in the complex systems (Fig. 6b). When employing a 1.4 Å probe diameter, the MolSA closely resembles a region of van der Waals surfaces. All compounds exhibited the typical van der Waals interface space during the in-silico analysis (Fig. 7a). Moreover, molecules derived PSA only from oxygen and nitrogen elements, and the chosen protein–ligand complexes displayed notable PSA values (Fig. 7b). The intermolecular fractions for the compounds and control drug are illustrated in Fig. 8. Each substance formed multiple bonds, including hydrogen, hydrophobic, ionic, and water bridging connections, throughout the 200 ns simulation period, and sustained these bonds until the conclusion of the experiment, thereby fostering a continuous interaction affinity with the selected proteins. Five key parameters were chosen to define the Gibbs free energy conditions following the simulation of protein–ligand complexes. The negative values of free energy binding upon receptor-ligand interaction indicate that the interaction occurs spontaneously with a higher affinity between the ligands and the targeted protein. We reported a positive value for r_psp_MMGBSA_dG_Bind_Solv_GB, indicating that the studied compounds do not readily dissolve in water while interacting with the targeted protein (Fig. 9). Notably, the results of this study demonstrated that all the chosen phytocompounds displayed typical simulation thermal binding Gibbs free energies, ranging from − 34.59 to − 67.29 kcal/mol, in comparison to the control drug (− 53.01 kcal/mol). Finally, trajectory analysis of the studied compounds demonstrated thermodynamically stable receptor-ligand complexes throughout the 200 ns time-scale (Fig. S5).

Figure 5.

(a) The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values of the E6 protein (PDB ID: 4XR8) retrieved from the Cα atoms of the complex system together with the five best lead compounds and control drug. (b) The root-mean square fluctuation (RMSF) values of the E6 protein (PDB ID: 4XR8) with the five best lead compounds and the control drug retrieved from the Cα atoms of the complex system. The selected compounds CID-5318517 (andrographolide), CID-5281703 (wogonin), CID-5280794 (stigmasterol), CID-15411809 (AP7), CID-5280443 (apigenin) and control drug (CID-57469; imiquimod) in the complex with the protein are represented by black, orange, gray, yellow, blue, and green color, respectively.

Figure 6.

The (a) radius of gyration (Rg) and (b) solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of the protein–ligand combination compounds (measured at 200 ns simulation). The selected compounds CID-5318517 (andrographolide), CID-5281703 (wogonin), CID-5280794 (stigmasterol), CID-15411809 (AP7), CID-5280443 (apigenin) and control drug (CID-57469; imiquimod) in the complex with the protein are represented by black, orange, gray, yellow, blue, and green color, respectively.

Figure 7.

The molecular surface area (MolSA) and polar surface area (PSA) of the protein–ligand compounds (200 ns simulated interaction diagrams). (a) Comparison of MolSA values among top five compounds and the control drug. (b) Comparison of PSA values among top five compounds and the control drug. The selected compounds CID-5318517 (andrographolide), CID-5281703 (wogonin), CID-5280794 (stigmasterol), CID-15411809 (AP7), CID-5280443 (apigenin) and control drug (CID-57469; imiquimod) in the complex with the protein are represented by black, orange, gray, yellow, blue, and green color, respectively.

Figure 8.

The interactions between protein and ligands identified during the 200 ns simulation are shown in the stacked bar charts. Herein, bar plots are showing intermolecular fractions for the compounds (a) andrographolide, (b) wogonin, (c) stigmasterol, (d) AP7, (e) apigenin and the control drug (f) imiquimod.

Figure 9.

Post-simulation thermal MM-GBSA. The five top compounds (CID-318517, CID-5281703, CID-5280794, CID-15411809, CID-5280443) and the control (CID-57469) drug containing the targeted protein (E6) were subjected to a post-simulation thermal MP-GBSA analysis. The cumulative MM-GBSA binding free energy was determined by contributions from Coulombic forces (Coulomb), covalent interactions (Covalent), hydrogen bonding (H-bond), lipophilic interactions (Lipo), π-π packing interactions (Packing), generalized solvent effects, and van der Waals forces (VDW).

Discussion

Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide, with about 660,000 new cases and 350,000 deaths annually, mainly caused by high-risk HPV genotypes like HPV-16 and HPV1810,11. As drug resistance increases in conventional CC treatments, the search for superior candidates intensifies, with natural plant-derived phytochemicals offering promising alternatives for cancer therapy19,29. Therefore, our aim was to discover potential drug candidates from A. paniculata that effectively target the E6 protein of the HPV-16 through computational methods. We investigated the thermodynamic characteristics of five phytocompounds—stigmasterol, AP7, andrographolide, apigenin and wogonin—found in A. paniculata plant. Thermodynamic analysis revealed that the studied compounds displayed lower hardness and relatively higher softness values in comparison to two control drugs (control 1: imiquimod and control 2: podophyllotoxin). Additionally, it was evident that the studied compounds were more reactive than the controls, indicating better thermodynamic characteristics with enhanced reaction potential and interactions with target. Thermodynamic calculations predict reaction kinetics and molecule stability. A more negative value as a output of the thermodynamic calculations suggests a higher likelihood of binding with other reacting molecules30. The thermodynamic traits of the selected compounds are consistent with findings from lead molecular orbital analysis, suggesting lower hardness and comparatively higher softness values. The majority of compounds discussed displayed greater reactivity than the controls, underscoring the essential role of lead molecular orbitals in determining a molecule's chemical reactivity and stability31. They were also exhibited higher dipole moments compared to the control drugs, indicating potential better solubility, permeability, and oral bioavailability. Studies have shown that compounds with higher dipole moments generally have greater water solubility and are less likely to be absorbed through lipophilic membranes32,33. Andrographolide exhibited the lowest HOMO energy, while stigmasterol demonstrated the highest energy gap among the compounds examined, with the order of energy gaps as follows: wogonin < AP7 < apigenin < imiquimod < podophyllotoxin < andrographolide < stigmasterol. Soft molecules with a smaller energy gap tend to be more reactive than harder molecules. Lower HOMO–LUMO gap indicates the less stability of the molecule as the electronic transition is more likely to happen upon excitation. Therefore, wogonin supposed to has high chemical reactivity, while stigmasterol has low reactivity based on their HOMO–LUMO energy gap24,34. In MEP analysis, oxygen atoms displayed the most negative potential, while hydrogen atoms exhibited the highest positive potential. Wogonin exhibited the highest potentials, while stigmasterol had the lowest. The MEP is a crucial parameter for assessing the active sites of electrophilic and nucleophilic regions of a chemical in the context of studying biological identification processes35. The FTIR spectroscopy analysis indicated that the vibrational frequencies associated with C=H, C=C, C=O and O=H bonds in the investigated compounds closely matched the experimental values, providing confirmation of the presence of these bonds within their structures. Vibrational spectroscopy provides a unique chance to explore the molecular composition of unknown substances, offering deep insights into their chemical information and structural arrangement due to its high sensitivity36,37. The findings of the UV–visible spectral analysis (TD-DFT calculations) revealed that AP7 displayed the lowest energy and greatest stability, as evidenced by its absorption peak occurring at a longer wavelength. Conversely, stigmasterol demonstrated the highest energy and thus the lowest stability, as its absorption peak occurred at a shorter wavelength compared to the other compounds discussed. Stigmasterol and apigenin exhibited higher stability compared to the control drug imiquimod (control 1), whereas podophyllotoxin (control 2) outperformed apigenin, wogonin and stigmasterol in terms of stability. TD-DFT calculations for UV–visible spectral analysis are crucial for understanding electronic transitions within molecules and provide insight into the stability of the compounds studied38. Docking the selected compounds against the drug target E6 (4xr8) resulted in higher binding scores than the controls. Each of the five selected compounds exhibited higher binding affinity than the controls. The docking findings from this study demonstrated that the studied compounds form stable complexes, indicating potential effectiveness and enhanced specificity. Molecular screening plays a crucial role in studying the interactions between drugs and biomolecules, enhancing the efficiency of drug design and discovery processes39,40.

A notable discovery in this study is the unique interaction patterns displayed by all five compounds with the target E6 protein, emphasizing the variability in protein–ligand interactions in HPV. The five compounds interacting with protein E6 exhibited diverse non-covalent interactions. Stigmasterol formed alkyl bonds, while AP7 and andrographolide showed conventional hydrogen bonds. Apigenin displayed hydrophobic interactions and wogonin formed regular hydrogen bonds whereas E6 protein showed various hydrophobic interactions. These interactions are pivotal in anchoring the drug at the desired site, enhancing its efficacy, and altering its binding affinity. Samant et al.41 examined the molecular interactions between HIV and antiviral medications targeting HPV-18 E6 protein, while Kotadiya and Georrge42 identified multiple potential therapeutics derived from natural products against HPV using an in-silico approach. Recently, Proboningrat et al.43 demonstrated the therapeutic potential of several natural compounds, including Apigenin, against HPV-18 E6 protein. In another study, the anti-tumor and pharmacological attributes of stigmasterol were explored using a T lymphoblastic leukemia cell line, E6-1/Jurkat44. Salaria et al.45 identified 19 phytoconstituents in Indian barberry plant (Berberis aristate), among which stigmasterol was found as the highly effective medication for treating HPV. Andrographolide and its derivatives exhibited a potential effect on HPV-16 pseudo-virus infection and viral oncogene expression in cervical carcinoma cells43. Moreover, wogonin has demonstrated efficient induction of apoptosis in human cervical cancer cells by downregulating the expression of E6 and E746.

Another important finding of our study is that the drug likeness and ADMET characteristics of the studied compounds and controls, adhered to Lipinski's "rule of 5". All compounds meet Lipinski's criteria, with lower molecular weights compared to controls. Additionally, physiochemical features suggest their potential as drug candidates. Solubility and gastrointestinal absorption of the compounds generally match or exceed controls, except for stigmasterol. Drug development is directly related to water solubility, which determines drug uptake, transfer, and removal from the body47. Drugs with poor solubility will be eliminated from the body without entering the bloodstream, which will result in the drug's pharmacological inactivity48. Through an examination of the toxicological effects of the screened compounds, it was determined that none exhibited cytotoxicity, indicating their absence of hepatotoxic and mutagenic effects. Additionally, we conducted MD simulations to validate the structural compactness of protein–ligand complexes and evaluate the durability of their interactions under the physiological conditions present in the human body. A 200-ns MD simulation was conducted, integrating pertinent physiological and physicochemical data49,50. Higher RMSF values observed in complex systems indicate a decrease in the compactness of the protein–ligand complex, whereas lower RMSD values signify greater stability of the compounds51. Except for CID-5280443 (apigenin) and CID-5280794 (stigmasterol), the therapeutic candidate compounds exhibited significant RMSD and RMSF values when compared to the control medication, indicating their potential interaction with the targeted protein. In the context of protein complexes, a lower Rg value indicates greater compactness, while a higher Rg value suggests the compounds' detachment from the protein. Our investigation revealed that the Rg values of the therapeutic candidate compounds were lower than those of the control medication containing the targeted protein. In MD simulation, ligands formed diverse connections with targeted protein, including hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, ionic bonding, and water bridge bonding. These interactions remained stable throughout the simulation, facilitating the establishment of potential binding between the ligands and the proteins. Furthermore, the MM-GBSA values of the studied compounds indicate their ability to maintain prolonged interactions with the target protein. Overall, the observed optimal properties of all compounds in the MD simulations align with earlier research findings52,53. Hence, the results of this in-silico study indicated that the screened compounds exhibited favorable attributes for interacting with the target protein, thus enhancing their reliability and consistency in drug development. These findings emphasize the potential suitability of these compounds for further investigation and therapeutic development against lethal cancers like CC. Given that the results of this study are solely generated from an in-silico computational approach, additional wet lab experiments for clinical verification and molecular functional characterization are necessary to validate the current findings. These steps are crucial to substantiate the present bioinformatic analysis before considering the clinical application of the screened phytocompounds in the treatment of CC.

Conclusion

Taken together, our data, for the first time, provide evidence that A. paniculata could be an alternative treatment for patients with CC. A chemical library was constructed using compounds sharing structural similarity to A. paniculata sourced from the PubChem database. The compounds were retrieved, further analyzed and screened on the criteria of binding energy, drug-likeness properties and ADMET parameters via computational techniques such as molecular docking and MD simulations. Considering the spectrochemical, pharmacokinetics properties, docking results and drug likeliness, five compounds—stigmasterol, AP7, andrographolide, apigenin and wogonin—emerged as potential inhibitors against the E6 protein of HPV-16. MD simulations demonstrated that the selected compounds maintained their stability within the active site of the E6 protein of HPV-16. The results indicated that the screened compounds exhibited enhanced biological activity, attributed to their lower affinity energy and higher binding strength towards the receptor of the target E6 protein of HPV. Their ability to form various complexes through different combinations underscores their validity as a starting point for drug design and development in the management of CC. Overall, this study identified promising inhibitors from A. paniculata against the HPV-16 E6 protein, offering potential new avenues for CC treatment and management.

Methods and materials

Protein structure preparation

The three-dimensional (3D) crystal structure of the HPV E6 protein (PDB ID: 4xr8) was retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank database (accessed: December 15, 2023, https://www.rcsb.org/), with a resolution of 2.25 Å. The BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer v4.5 software was utilized to eliminate hetero atoms, water molecules, and unnecessary residue connections54. Following this, energy minimization was performed using the Swiss-PDB Viewer v4.1.0 to mitigate unfavorable protein contacts39. Subsequently, optimized targets were identified to conduct molecular docking analysis against the E6 protein (PDB ID: 4xr8) of the HPV.

Retrieval and preparation of A. paniculata phytocompounds

In this study, we employed the curated database Indian Medicinal Plants, Phytochemistry and Therapeutics (IMPPAT) (accessed: December 20, 2023, https://cb.imsc.res.in/imppat/) to retrieve the phytocompounds of A. paniculata. IMPPAT contains a comprehensive collection of 1,742 Indian medicinal plants, 9596 phytochemicals along with other related information55. In this study, we selected 42 compounds from A. paniculata, known for their extensive antioxidant properties, anticancer effects, and antiviral activities56–58. We downloaded the 3D structures of 42 compounds of A. paniculata from the IMPPAT database in pdb file format. These compounds were isolated and prepared for multiple docking using PyRx virtual screening tool AutoDock Vina59. We selected imiquimod and podophyllotoxin as control drugs. Although many compounds targeting the E6 protein of HPV have entered clinical trials, there has been no significant advancement in this area23,60. However, recent studies have highlighted the potential of these compounds due to their antimitotic and antiviral activities61. Additionally, the treatment modalities of these two control drugs have been extensively investigated in several clinical trials61,62. The E6 dimerization interface emerges as a prominent target for small molecules aimed at disrupting DNA replication45. A total of 32 compounds (N = 32) out of the 42 analyzed had binding affinities higher than the control drugs imiquimod (− 8.7 kcal/mol) and podophyllotoxin (-7.9 kcal/mol) and were finally selected for further analysis (Table S1).

Geometry optimization and ligand preparation

Following screening, the 3D structures of the finally selected compounds (N = 32) and the two control drugs of the HPV (imiquimod; control 1 and podophyllotoxin; control 2) were downloaded from the PubChem database (accessed: December 24, 2023, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Subsequently, these structures underwent modification and geometry optimization using Gaussian v.09 software program63. The optimization procedure was carried out using Density Functional Theory (DFT) with the B3LYP method and the 6-31 g (d,p) basis set under gas phase conditions64. Additionally, TD-DFT was employed to calculate the electronic transition state. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), referred to as lead molecular orbitals, were calculated using DFT analysis to assess their chemical reactivity53. The Eqs. (1 and 2) 65 have been utilized to analyze the characteristics of molecular orbitals:

| 1 |

where: ΔE is the energy gap; εLUMO is the lowest occupied molecular orbit; εHUMO is the highest occupied molecular orbit; η is the chemical hardness; S is the chemical softness.

| 2 |

where: μ is the chemical potential; εLUMO is the lowest occupied molecular orbit; εHUMO is the highest occupied molecular orbit; χ is the electronegativity; ω is the electrophilicity index; μ is the chemical potential; η is the chemical hardness.

The obtained compounds were designated as ligands for the docking experiment.

Molecular docking analysis and visualization

The PyRx virtual screening software integrated with the AutoDock Vina v1.2.0 platform was used to conduct a molecular docking analysis to assess the molecular binding energy of the requisite protein with the chosen phytochemicals66,67. AutoDock Vina represents an open-source software for molecular docking and virtual screening, necessitating the 3D structures of receptor and ligand molecules in pdbqt file format to forecast their binding energy within studies focusing on receptor-ligand interactions67. Docking was executed without selecting the binding pockets with the compounds serving as the ligands and the protein acting as the macromolecules. However AutoDock Vina can automatically calculate the active site (a specific region, often a pocket or groove, on the protein’s surface where substrate molecules attach and undergo a chemical reaction) with the help of algorithms that are integrated to predict and identify potential binding pockets based on the receptor's 3D structure68. This analysis encompassed conducting rigid docking, wherein all rotatable bonds were converted into non-rotatable ones. The grid box position is a crucial factor in performing effective docking analysis, as it defines the specific area of the protein where the ligand docking will take place69. Regions outside the grid box were not considered during the docking process. In our analysis, the center grid box size was set to 59.5132 Å along the x-axis, 50.9758 Å along the y-axis, and 62.3999 Å along the z-axis, covering the protein regions of our interest. The binding pocket regions were identified by DoGSiteScorer and the grid box size was set based on the output provided by DoGSiteScorer70. Following the completion of the docking process, both the protein and the docked ligands were preserved in pdbqt format. This was undertaken to facilitate subsequent analysis of the docking score, non-bond interactions, and visualization. Additionally, BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer v4.5 was utilized to visualize the interacting amino acid residues and the various types of bonds formed during these interactions54.

Drug likeliness and pharmacokinetics properties prediction

An in-silico computational pharmacokinetics approach was used to determine the temporal dynamics of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET). Drug-likeness and pharmacokinetics parameters such as Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) in the ligands and protein were evaluated through the SwissADME web tool71. For toxicity prediction, we used Protox online server72. In this analysis, the Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) formats of all ligands and protein were retrieved from the PubChem database. Lipinski's rule of 5 was used to assess the drug-likeness of these protein-ligands complexes, ensuring that all properties are within the accepted range73. Comprehensively, all the significant ADMET parameters of the protein-ligands complexes was estimated and checked towards compliance with their standard ranges for their identification as suitable drug candidates.

Molecular dynamics simulation

To ensure the reliability of protein–ligand complex structures, approximately 200 ns (ns) of MDS were conducted. The “Desmond v3.6 Program” from Schrodinger (https://www.schrodinger.com/ac) was used to model the molecular dynamics of the protein–ligand complex structures in a Linux infrastructure74. The necessary ions, for instance, 0 + along with 0.15 M salt (Na+ and Cl-), were added randomly to the solvent solution to electrically neutralize the system. The protein-solvent system was built surrounding the ligand complex, and the framework of the system was minimized using the default protocol. Within individual Isothermal-Isobaric ensembles (NPT) assemblies, maintained at a pressure of 101,325 bar (1 atm) and a temperature of 300 K, 50 PS capture sessions totaling 1.2 kcal/mole energy were conducted prior to utilizing the Nose–Hoover temperature coupling and isotropic approach. The molecular dynamic simulation screenshots were generated using Schrodinger’s Maestro application, version 9.5. Analysis of the simulation event and evaluation of the MD simulation's reliability were conducted utilizing the interaction diagram derived from the Desmond modules within the Schrodinger suite. Relative stability of particular protein–ligand complex combinations was evaluated using information based on protein–ligand interactions (P-L), intrinsic hydrogen connections, root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), root mean square deviation (RMSD), solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) value, radius of gyration (Rg) value, polar surface area (PSA), and MolSA75.

Post MDS thermal MM-GBSA analysis

The calculation of molecular mechanics-generalized born surface area (MM-GBSA) was carried out to approximate the complex free energy over the course of the 200 ns simulation time, employing the thermal_mmgbsa.py Python module. Subsequently, the Desmond MD trajectory was segmented into 20 frame snapshots, and MM-GBSA was applied to isolate the ligand and receptor within each of these snapshots.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

M.A.I., M.S.H. and M.N.H. conceived and designed the study; S. H., M.H.S., S.A., M.A.M., A.T. and M.A.H. acquisition of data, analysis and writing original draft; M.A.H., M.A.I. and M.N.H. critical review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Data availability

The article contains the data utilized to support the results of the in-silico study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Md. Aminul Islam and Md. Shohel Hossain.

Contributor Information

Md. Aminul Islam, Email: aminul@pahmc.edu.bd.

M. Nazmul Hoque, Email: nazmul90@bsmrau.edu.bd.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-65112-2.

References

- 1.Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.74, 229–263. 10.3322/caac.21834 (2024). 10.3322/caac.21834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chhikara, B. & Parang, K. Global cancer statistics 2022: the trends projection analysis. Chem. Biol. Lett.10, 451 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruni, L. et al. Cervical cancer screening programmes and age-specific coverage estimates for 202 countries and territories worldwide: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health10, e1115–e1127. 10.1016/s2214-109x(22)00241-8 (2022). 10.1016/s2214-109x(22)00241-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arbyn, M. et al. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob. Health8, e191–e203. 10.1016/s2214-109x(19)30482-6 (2020). 10.1016/s2214-109x(19)30482-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das, S. et al. Molecular mechanisms augmenting resistance to current therapies in clinics among cervical cancer patients. Med. Oncol.40, 149. 10.1007/s12032-023-01997-9 (2023). 10.1007/s12032-023-01997-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uddin, A. K., Sumon, M. A., Pervin, S. & Sharmin, F. Cervical cancer in Bangladesh. South Asian J. Cancer12, 036–038 (2023). 10.1055/s-0043-1764202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davy, M. L., Dodd, T. J., Luke, C. G. & Roder, D. M. Cervical cancer: effect of glandular cell type on prognosis, treatment, and survival. Obstet. Gynecol.101, 38–45 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akash, S. et al. Novel computational and drug design strategies for inhibition of human papillomavirus-associated cervical cancer and DNA polymerase theta receptor by Apigenin derivatives. Sci. Rep.13, 16565 (2023). 10.1038/s41598-023-43175-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan, L. F., Rajagopal, M. & Selvaraja, M. An overview on the pathogenesis of cervical cancer. Curr. Trends Biotechnol. Pharm.17, 717–734 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perkins, R. B., Wentzensen, N., Guido, R. S. & Schiffman, M. Cervical cancer screening: a review. Jama330, 547–558 (2023). 10.1001/jama.2023.13174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma, X. & Yang, M. The correlation between high-risk HPV infection and precancerous lesions and cervical cancer. Am. J. Transl. Res.13, 10830 (2021). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plummer, M., Peto, J. & Franceschi, S. International collaboration of epidemiological studies of cervical cancer time since first sexual intercourse and the risk of cervical cancer. Int. J. Cancer130(11), 2638–2644 (2012). 10.1002/ijc.26250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pal, A. & Kundu, R. Human papillomavirus E6 and E7: the cervical cancer hallmarks and targets for therapy. Front. Microbiol.10, 510168 (2020). 10.3389/fmicb.2019.03116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng, Q. et al. HPV E6/E7: insights into their regulatory role and mechanism in signaling pathways in HPV-associated tumor. Cancer Gene Therapy31, 9–17 (2024). 10.1038/s41417-023-00682-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szymonowicz, K. A. & Chen, J. Biological and clinical aspects of HPV-related cancers. Cancer Biol. Med.17, 864 (2020). 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2020.0370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galani, E. & Christodoulou, C. Human papilloma viruses and cancer in the post-vaccine era. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.15, 977–981 (2009). 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03032.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noratto, G. et al. Antitumor potential of dark sweet cherry sweet (Prunus avium) phenolics in suppressing xenograft tumor growth of MDA-MB-453 breast cancer cells. J. Nutr. Biochem.84, 108437 (2020). 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2020.108437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hampson, L., Martin-Hirsch, P. & Hampson, I. N. An overview of early investigational drugs for the treatment of human papilloma virus infection and associated dysplasia. Exp. Opinion Invest. Drugs24, 1529–1537 (2015). 10.1517/13543784.2015.1099628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaobotse, G. et al. The use of African medicinal plants in cancer management. Front. Pharmacol.14, 1122388 (2023). 10.3389/fphar.2023.1122388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sahsuvar, S., Guner, R., Gok, O. & Can, O. Development and pharmaceutical investigation of novel cervical cancer-targeting and redox-responsive melittin conjugates. Sci. Rep.13, 18225 (2023). 10.1038/s41598-023-45537-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehmood, A., Kaushik, A. C., Wang, Q., Li, C.-D. & Wei, D.-Q. Bringing structural implications and deep learning-based drug identification for KRAS mutants. J. Chem. Inform. Model.61, 571–586 (2021). 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehmood, A., Nawab, S., Jin, Y., Kaushik, A. C. & Wei, D.-Q. Mutational impacts on the N and C terminal domains of the MUC5B protein: a transcriptomics and structural biology study. ACS Omega8, 3726–3735 (2023). 10.1021/acsomega.2c04871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, Z. et al. Combination of furosemide, gold, and dopamine as a potential therapy for breast cancer. Funct. Integrative Genom.23, 94 (2023). 10.1007/s10142-023-01007-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aihara, J.-I. Reduced HOMO−LUMO gap as an index of kinetic stability for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. A103, 7487–7495. 10.1021/jp990092i (1999). 10.1021/jp990092i [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Makhzumi, Q., Abdullah, H. & Al-Ani, R. Theoretical study of N-Methyl-3-Phenyl-3-(4-(Trifluoromethyl) Phenoxy) Propan as a drug and its five derivatives. J. Biosci. Med.06, 80–98. 10.4236/jbm.2018.68007 (2018). 10.4236/jbm.2018.68007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar, G. & Surapaneni, S. Role of drug metabolism in drug discovery and development. Med. Res. Rev.21, 397–411. 10.1002/med.1016 (2001). 10.1002/med.1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao, J. et al. Revisiting aldehyde oxidase mediated metabolism in drug-like molecules: an improved computational model. J. Med. Chem.63, 6523–6537. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01895 (2020). 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Islam, M. R. et al. Ligand-based drug design against Herpes Simplex Virus-1 capsid protein by modification of limonene through in silico approaches. Sci. Rep.14, 9828. 10.1038/s41598-024-59577-4 (2024). 10.1038/s41598-024-59577-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trinidad-Calderón, P. A., Varela-Chinchilla, C. D. & García-Lara, S. Natural peptides inducing cancer cell death: mechanisms and properties of specific candidates for cancer therapeutics. Molecules26, 7453 (2021). 10.3390/molecules26247453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azam, F. et al. NSAIDs as potential treatment option for preventing amyloid β toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease: an investigation by docking, molecular dynamics, and DFT studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.36, 2099–2117 (2018). 10.1080/07391102.2017.1338164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saravanan, S. & Balachandran, V. Quantum chemical studies, natural bond orbital analysis and thermodynamic function of 2, 5-dichlorophenylisocyanate. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectr.120, 351–364 (2014). 10.1016/j.saa.2013.10.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das, A., Das, A. & Banik, B. K. Influence of dipole moments on the medicinal activities of diverse organic compounds. J. Indian Chem. Soc.98, 100005. 10.1016/j.jics.2021.100005 (2021). 10.1016/j.jics.2021.100005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira, F. & Aires-de-Sousa, J. Machine learning for the prediction of molecular dipole moments obtained by density functional theory. J. Cheminform.10, 43. 10.1186/s13321-018-0296-5 (2018). 10.1186/s13321-018-0296-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miar, M., Shiroudi, A., Pourshamsian, K., Oliaey, A. R. & Hatamjafari, F. Theoretical investigations on the HOMO–LUMO gap and global reactivity descriptor studies, natural bond orbital, and nucleus-independent chemical shifts analyses of 3-phenylbenzo[d]thiazole-2(3H)-imine and its para-substituted derivatives: Solvent and substituent effects. J. Chem. Res.45, 147–158. 10.1177/1747519820932091 (2021). 10.1177/1747519820932091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mol, G. S. et al. Structural activity, fungicidal activity and molecular dynamics simulation of certain triphenyl methyl imidazole derivatives by experimental and computational spectroscopic techniques. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectr.212, 105–120 (2019). 10.1016/j.saa.2018.12.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Movasaghi, Z. & Rehman, S. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy of biological tissues. Appl. Spectr. Rev.43, 134–179 (2008). 10.1080/05704920701829043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Talari, A. C. S., Martinez, M. A. G., Movasaghi, Z., Rehman, S. & Rehman, I. U. Advances in Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy of biological tissues. Appl. Spectr. Rev.52, 456–506 (2017). 10.1080/05704928.2016.1230863 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo, Y., Liu, C., Ye, R. & Duan, Q. Advances on water quality detection by uv-vis spectroscopy. Appl. Sci.10, 6874 (2020). 10.3390/app10196874 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rahman, M. S. et al. Epitope-based chimeric peptide vaccine design against S, M and E proteins of SARS-CoV-2, the etiologic agent of COVID-19 pandemic: an in silico approach. PeerJ8, e9572 (2020). 10.7717/peerj.9572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoque, M. N. et al. Differential gene expression profiling reveals potential biomarkers and pharmacological compounds against SARS-CoV-2: Insights from machine learning and bioinformatics approaches. Front. Immunol.13, 918692 (2022). 10.3389/fimmu.2022.918692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Samant, L. R., Sangar, V. C., Shahid Chaudhary, S. C. & Abhay Chowdhary, A. C. In silico molecular interactions of HIV antiviral drugs against HPV type 18 E6 protein. (2015).

- 42.KOTADIYA, R. & GEORRGE, J. J. 1. IN SILICO APPROACH TO IDENTIFY PUTATIVE DRUGS FROM NATURAL PRODUCTS FOR HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS (HPV) WHICH CAUSE CERVICAL CANCER By ROHITKUMAR KOTADIYA1 AND JOHN J. GEORRGE2. Life Sciences Leaflets62, 1 to 13–11 to 13 (2015).

- 43.Proboningrat, A. et al. In silico study of natural inhibitors for human papillomavirus-18 E6 protein. Res. J. Pharm. Technol.15, 1251–1256 (2022). 10.52711/0974-360X.2022.00209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang, X. et al. Advances in Stigmasterol on its anti-tumor effect and mechanism of action. Front. Oncol.12, 1101289 (2022). 10.3389/fonc.2022.1101289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salaria, D. et al. Phytoconstituents of traditional Himalayan Herbs as potential inhibitors of human papillomavirus (HPV-18) for cervical cancer treatment: an in silico approach. PLoS ONE17, e0265420. 10.1371/journal.pone.0265420 (2022). 10.1371/journal.pone.0265420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim, M. S. et al. Wogonin induces apoptosis by suppressing E6 and E7 expressions and activating intrinsic signaling pathways in HPV-16 cervical cancer cells. Cell Biol. Toxicol.29, 259–272. 10.1007/s10565-013-9251-4 (2013). 10.1007/s10565-013-9251-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van de Waterbeemd, H. & Gifford, E. ADMET in silico modelling: towards prediction paradise?. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.2, 192–204. 10.1038/nrd1032 (2003). 10.1038/nrd1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kar, S. & Leszczynski, J. Open access in silico tools to predict the ADMET profiling of drug candidates. Expert Opin. Drug. Discov.15, 1473–1487. 10.1080/17460441.2020.1798926 (2020). 10.1080/17460441.2020.1798926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abdullah, A. et al. Molecular dynamics simulation and pharmacoinformatic integrated analysis of bioactive phytochemicals from Azadirachta indica (Neem) to treat diabetes mellitus. J. Chem.2023, 1–19 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andalib, K. S. et al. Identification of novel MCM2 inhibitors from Catharanthus roseus by pharmacoinformatics, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation-based evaluation. Inform. Med. Unlocked39, 101251 (2023). 10.1016/j.imu.2023.101251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al Saber, M. et al. A comprehensive review of recent advancements in cancer immunotherapy and generation of CAR T cell by CRISPR-Cas9. Processes10, 16 (2021). 10.3390/pr10010016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khan, A. M. et al. <em>In vitro</em> and <em>in silico</em> investigation of garlic’s (<em>Allium sativum</em>) bioactivity against 15-lipoxygenase mediated inflammopathies. J. Herbmed. Pharmacol.12, 283–298. 10.34172/jhp.2023.31 (2023). 10.34172/jhp.2023.31 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hossain, M. A. et al. Genome-wide investigation reveals potential therapeutic targets in shigella spp.. BioMed. Res. Int.2024, 5554208 (2024). 10.1155/2024/5554208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Biovia, D. S. & Dsme, R. San Diego: Dassault Systèmes. Release4 (2015).

- 55.Mohanraj, K. et al. IMPPAT: a curated database of I ndian M edicinal P lants, P hytochemistry A nd T herapeutics. Sci. Rep.8, 4329 (2018). 10.1038/s41598-018-22631-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naomi, R. et al. Mechanisms of natural extracts of andrographis paniculata that target lipid-dependent cancer pathways: a view from the signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 5972 (2022). 10.3390/ijms23115972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hossain, M. S., Urbi, Z., Sule, A. & Rahman, K. H. Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Wall. ex Nees: a review of ethnobotany, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. The Scientific World Journal2014 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Adiguna, S. B. et al. Antiviral activities of andrographolide and its derivatives: mechanism of action and delivery system. Pharmaceuticals14(11), 1102 (2021). 10.3390/ph14111102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huey, R., Morris, G. M. & Forli, S. Using AutoDock 4 and AutoDock vina with AutoDockTools: a tutorial. Scripps Res. Inst. Mol. Graphics Lab.10550, 1000 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Duncan, C. L., Gunosewoyo, H., Mocerino, M. & Payne, A. D. Small Molecule Inhibitors of Human Papillomavirus: A Review of Research from 1997 to 2021. Curr Med Chem, 10.2174/0929867331666230713165407 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Ardalani, H., Avan, A. & Ghayour-Mobarhan, M. Podophyllotoxin: a novel potential natural anticancer agent. Avicenna J. Phytomed.7, 285 (2017). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murray, M. L. et al. Human papillomavirus infection: protocol for a randomised controlled trial of imiquimod cream (5%) versus podophyllotoxin cream (0.15%), in combination with quadrivalent human papillomavirus or control vaccination in the treatment and prevention of recurrence of anogenital warts (HIPvac trial). BMC Med. Res. Methodol.18, 1–9 (2018). 10.1186/s12874-018-0581-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng, G. et al. Gaussian 09. Gaussian Inc., Wallingford CT, 48 (2009).

- 64.Khan, R. A. et al. Diterpenes/diterpenoids and their derivatives as potential bioactive leads against dengue virus: a computational and network pharmacology study. Molecules26, 6821 (2021). 10.3390/molecules26226821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Uzzaman, M. et al. Physicochemical, spectral, molecular docking and ADMET studies of Bisphenol analogues; a computational approach. Inform. Med. Unlocked25, 100706 (2021). 10.1016/j.imu.2021.100706 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dallakyan, S. & Olson, A. J. Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. Chemical biology: methods and protocols, 243–250 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Eberhardt, J., Santos-Martins, D., Tillack, A. F. & Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J. Chem. Inform. Model.61, 3891–3898 (2021). 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem.31, 455–461. 10.1002/jcc.21334 (2010). 10.1002/jcc.21334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xing, C., Chen, P. & Zhang, L. Computational insight into stability-enhanced systems of anthocyanin with protein/peptide. Food Chem. Mol. Sci.6, 100168 (2023). 10.1016/j.fochms.2023.100168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Volkamer, A., Kuhn, D., Rippmann, F. & Rarey, M. DoGSiteScorer: a web server for automatic binding site prediction, analysis and druggability assessment. Bioinformatics28, 2074–2075. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts310 (2012). 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pliska, V., Testa, B. & van de Waterbeemd, H. In Lipophilicity in Drug Action and Toxicology 1–6 (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, 1996).

- 72.Banerjee, P., Kemmler, E., Dunkel, M. & Preissner, R. ProTox 30: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res, 10.1093/nar/gkae303 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Lipinski, C. A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol.1, 337–341. 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007 (2004). 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.El Khoury, L. et al. Comparison of affinity ranking using AutoDock-GPU and MM-GBSA scores for BACE-1 inhibitors in the D3R Grand Challenge 4. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des.33, 1011–1020 (2019). 10.1007/s10822-019-00240-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rahman, M. S. et al. In vivo neuropharmacological potential of gomphandra tetrandra (wall.) sleumer and in-silico study against β-amyloid precursor protein. Processes9, 1449 (2021). 10.3390/pr9081449 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The article contains the data utilized to support the results of the in-silico study.