Abstract

Background

There is no universally accepted definition for surgical prehabilitation. The objectives of this scoping review were to (1) identify how surgical prehabilitation is defined across randomised controlled trials and (2) propose a common definition.

Methods

The final search was conducted in February 2023 using MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Cochrane. We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of unimodal or multimodal prehabilitation interventions (nutrition, exercise, and psychological support) lasting at least 7 days in adults undergoing elective surgery. Qualitative data were analysed using summative content analysis.

Results

We identified 76 prehabilitation trials of patients undergoing abdominal (n=26, 34%), orthopaedic (n=20, 26%), thoracic (n=14, 18%), cardiac (n=7, 9%), spinal (n=4, 5%), and other (n=5, 7%) surgeries. Surgical prehabilitation was explicitly defined in more than half of these RCTs (n=42, 55%). Our findings consolidated the following definition: ‘Prehabilitation is a process from diagnosis to surgery, consisting of one or more preoperative interventions of exercise, nutrition, psychological strategies and respiratory training, that aims to enhance functional capacity and physiological reserve to allow patients to withstand surgical stressors, improve postoperative outcomes, and facilitate recovery.’

Conclusions

A common definition is the first step towards standardisation, which is needed to guide future high-quality research and advance the field of prehabilitation. The proposed definition should be further evaluated by international stakeholders to ensure that it is comprehensive and globally accepted.

Keywords: prehabilitation, pre-rehabilitation, preoperative, pre-surgery, Enhanced Recovery After Surgery

Editor's key points.

-

•

Despite the widespread acceptance of surgical prehabilitation, there is no universally accepted definition.

-

•

This scoping review aimed to identify how surgical prehabilitation is defined across randomised controlled trials and use this information to propose a common definition.

-

•

A synthesis of 76 randomised controlled trials identified a common definition as a first step towards standardisation to guide future research of surgical prehabilitation.

The term ‘prehabilitation’ was first mentioned in the British Medical Journal in 1946 as a programme to prepare military recruits for physical and cognitive testing.1 In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the concept of prehabilitation as a therapeutic health intervention was introduced to the field of elective surgery as inspiratory muscle training before lung resection2 and before coronary artery bypass graft surgery.3 In 2007, prehabilitation was initiated before knee arthroplasty4 and then before lumbar spinal surgery5 using exercise therapy. By 2013, prehabilitation interventions were used to support oncological surgical care pathways, including colorectal,6,7 lung,8 and oesophageal9 cancers.

As the field of cancer prehabilitation research progressed, a definition was proposed by Silver and Baima10: ‘Cancer prehabilitation may be defined as a process on the continuum of care that occurs between the time of cancer diagnosis and the beginning of acute treatment, includes physical and psychological assessments that establish a baseline functional level, identifies impairments, and provides targeted interventions that improve a patient's health to reduce the incidence and the severity of current and future impairments'. Although this definition has been extensively cited, a common definition for surgical prehabilitation is still missing more than two decades after the initial published trials. This lack of consensus is an important issue as it may partly explain the heterogeneity in interventions and outcomes across surgical prehabilitation trials, which creates difficulties in pooling data and limits the certainty of the evidence. In a recent umbrella review of 55 systematic reviews on preoperative prehabilitation, only 15 individual reviews could be pooled for meta-analyses to measure the overall certainty of effect as a result of heterogeneity.11 Despite this limitation, prehabilitation was found to improve functional recovery after oncological surgeries with moderate certainty, while the certainty of the evidence for non-oncological surgeries was rated as low or critically low. One of the key priorities proposed to improve the quality and certainty of surgical prehabilitation evidence was to reach consensus around how this high-priority preoperative intervention is defined.11

To address this gap, we conducted a scoping review with the aim of consolidating a common definition for surgical prehabilitation as the first step towards consensus on a universally accepted definition. A clear definition will help guide future quality randomised control trials (RCTs) to generate robust evidence regarding the efficacy of surgical prehabilitation on meaningful outcomes.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a scoping review to synthesise a common definition of surgical prehabilitation. This review was performed in accordance with the framework suggested by Arksey and O'Malley12 and recommendations of Levac and colleagues,13 which include the following five essential steps: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) selecting studies; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarising, and reporting the results. A multidisciplinary team composed of prehabilitation health researchers and practitioners designed, charted, analysed, and interpreted the results of this study. Reporting of our findings followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist.14 A detailed description of the methodology, including the search strategy, study selection, and data charting has been published.15,16

Identifying the research question

The objectives of this scoping review were to (1) identify how surgical prehabilitation is defined across RCTs and (2) consolidate a common definition for future research.

Identifying relevant studies

We focused our search on published ‘prehabilitation’ labelled (in title, abstract or keywords) trials, in which the participants were randomised to different groups (independent of the type and method of randomisation). Prehabilitation labelled trials were then included if the following working definition of prehabilitation was met15, 16, 17, 18, 19: unimodal intervention consisting of exercise, nutrition, or psychological support, or a multimodal intervention that includes exercise, nutrition, or psychological support with or without other interventions, undertaken for ≥7 days before surgery to optimise a patient's preoperative condition and improve postoperative outcomes. The search strategy was developed by a librarian (GG; Supplementary Appendix 1). The first search was conducted on March 25, 202215 and was updated using the same strategy and with the same librarian on February 22, 2023. Six bibliographic databases were searched: MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Cochrane. No date restrictions were applied. The reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and narrative reviews were hand searched for additional relevant articles.

Study selection

Two independent reviewers used the Rayyan web application (www.rayyan.ai; Rayyan Systems Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) to screen titles and abstracts for inclusion (in the initial search DE and GDT, for the updated search CG and CFG). Studies were considered for the full-text review if the following criteria were met: (1) studies delivering a ‘prehabilitation’ labelled programme before surgery for adult patients (aged ≥18 yr) and in accordance with the aforementioned definition, and (2) were primary RCTs (including pilot and feasibility RCTs) with interventions lasting at least 7 days (a period consistent with enhanced recovery after surgery initiatives, not prehabilitation). Exclusion criteria were narrative reviews, editorials, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, scoping reviews, pooled analyses, secondary analyses, study protocols, consensus guidelines, conference abstracts, publications not in English or French, and isolated medical treatments (e.g. medication management alone). The full-text review was performed independently (in the initial search by DE and GDT, for the updated search by CG and CFG). All disagreements between reviewers were addressed by discussion until a consensus was reached.

Charting the data and analysis

Charting of the data (CFG and NB) included baseline study characteristics (author, year of publication, surgical speciality, and cancer type) published elsewhere.16 Intervention characteristics along with explicit and implicit definitions of surgical prehabilitation were extracted from the main manuscript and entered into the data charting sheet (MS Excel 2010, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

Intervention characteristics and definition components were quantified using counts and proportions. The qualitative text was analysed by two independent coders (CFG and NB) using summative content analysis, which involves familiarisation with the text; coding, counting, and comparisons of codes; and interpretation of the underlying meaning of the content.20,21 Definition components, as words or small phrases, were assigned codes using two approaches: pre-determined codes (i.e. deductive approach) and ‘ground-up’ codes based on the data set (i.e. inductive approach).20 The occurrence of each identified code was tabulated.20 Investigator and method triangulation was used to ensure the trustworthiness of the analysis by reducing the influence of individual biases.22 That is, two independent coders and two content analysis approaches (inductive and deductive) were used to form the common definition. The first coder used an inductive coding strategy that prioritised the most prevalent keywords in the explicit and implicit definitions provided by the study authors.20 Codes with similar meanings were grouped under an overarching category.21 The categories with ≥10 counts were included in the final inductive definition, representing the most frequently stated words of each category. The threshold of 10 counts was pre-specified (arbitrarily) to denote commonality across trials. The second coder used a deductive approach by pre-specifying important categories before analysis (purpose or goal, descriptor of the intervention, intervention type, timing, and target population) guided by the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) reporting guidelines for interventions.23 In the deductive approach, the TIDieR framework was prioritised regardless of the frequency of the individual codes. The inductive and deductive definitions were then compared to form a consolidated extensional definition (i.e. lists all things that are applicable to the defined subject) that represents typical surgical prehabilitation programmes.24

Results

Search findings

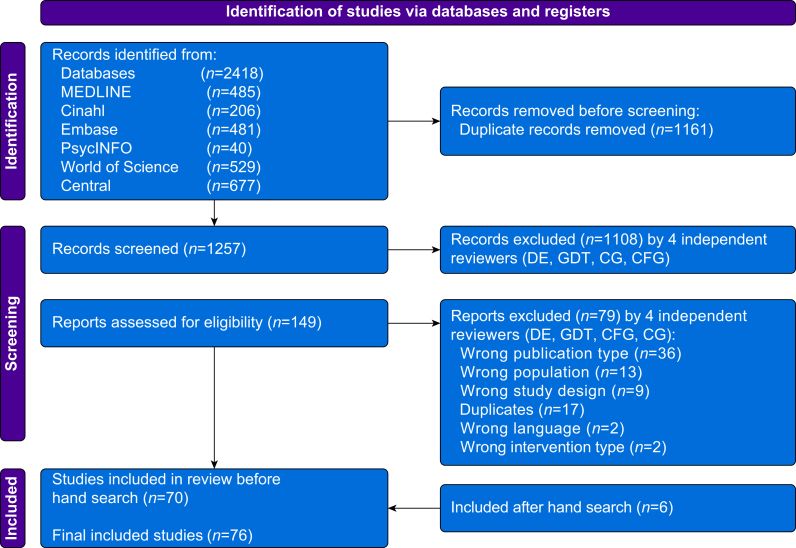

Our search identified 1257 unique articles (Fig. 1). After the abstract screening, 149 articles were suitable for the full-text review. A total of 79 articles were excluded because of publication type (n=36), population (n=13), study design (n=9), additional duplicates (n=17), language (n=2), and intervention type (n=2), leaving 70 articles. Hand searching produced six additional articles. A total of 76 articles were thus included in the final review.5,8,25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98

Fig 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Study characteristics

A total of 76 RCTs met the inclusion criteria.16 Trials included abdominal (26/76, 34%), orthopaedic and spinal (24/76, 32%), thoracic (14/76, 18%), cardiac (7/76, 9%), and other types (5/76, 7%) of surgeries. Surgical prehabilitation was explicitly defined in more than one-half of the RCTs (42/76, 55%; Table 1). Trials that did not report an explicit definition provided an explicit description of the intervention such as ‘ … maintaining good exercise capacity using aerobic and inspiratory muscle training program’75 or ‘short-term HIIT program was intended to augment preoperative physiological reserves and to facilitate postoperative functional recovery’.57 More than one-half of the explicit definitions (n=42) were from exercise-only trials (22/42, 52%) and about one-third originated from multimodal intervention trials (15/42, 36%). Together, nutritional-only and psychological-only prehabilitation accounted for 12% (5/42) of the RCTs providing an explicit definition. One-half of the trials with an explicit definition stemmed from the oncology literature (21/42). Only 14% (6/42) and 5% (2/42) of definitions were derived from RCTs of thoracic and cardiac surgical populations, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline study characteristics.

| Characteristics | Number of trials (n=76), n (%) | Trials with an explicit definition (n=42), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Type of prehabilitation program | ||

| Exercise only | 41 (54) | 22 (52) |

| Multimodal | 25 (33) | 15 (36) |

| Nutrition only | 3 (4) | 2 (5) |

| Psychological support only | 3 (4) | 3 (7) |

| Respiratory only | 3 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Pelvic floor training only | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Population included | ||

| Oncological surgery | 35 (46) | 21 (50) |

| Non-oncological surgery | 33 (43) | 17 (41) |

| Mixed cohort | 8 (11) | 4 (10) |

| Type of surgical population | ||

| Abdominal surgery | 26 (34) | 18 (43) |

| Orthopaedic and spinal surgeries | 24 (32) | 14 (33) |

| Thoracic surgery | 14 (18) | 6 (14) |

| Cardiac surgery | 7 (9) | 2 (5) |

| Other surgeries∗ | 5 (7) | 2 (5) |

∗Including breast-only and mixed cohorts.

Defining surgical prehabilitation

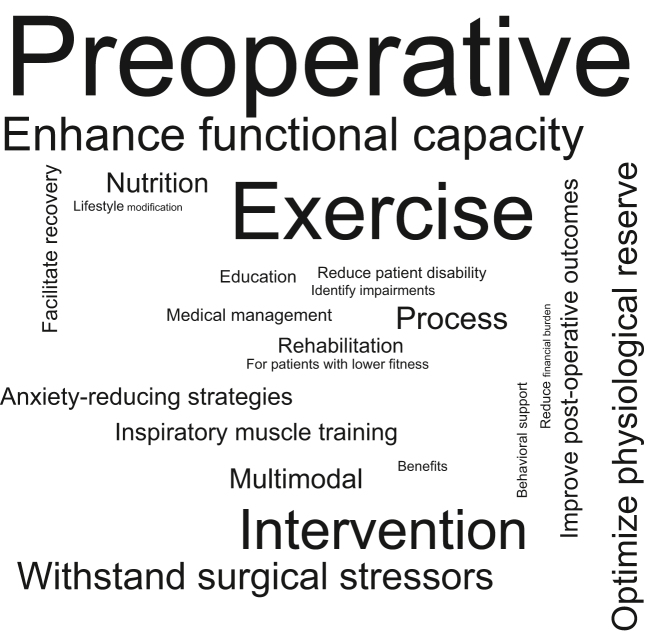

For both inductive and deductive qualitative methods, identified categories and predominant codes across all explicit definitions and descriptions are shown in Table 2. Findings from the inductive approach revealed 23 different categories (i.e. codes with similar content or meaning). Nearly three-quarters (n=55) of trials included ‘physical activity’ in their definition and used the codes ‘exercise/exercise therapy’ (n=25, 33%) most often. Forty-two percent (n=32) of trials used a ‘descriptor of prehabilitation’ category with the most prevalent code being ‘intervention’ (n=16, 21%). The category of ‘increasing function’ was reported in more than one-third (n=28, 37%) of trials with the code ‘enhance functional capacity’ being the most prevalent (n=17, 22%). When using the deductive approach, similar results were observed: the codes ‘enhance functional capacity/aerobic capacity/physical fitness’ (n=28, 37%) and ‘exercise’ (n=42, 55%) were also the most frequently reported (after the code ‘preoperative’). Ten inductive categories were excluded from the definition as they were infrequently (<10 counts) reported, including ‘rehabilitation’, ‘treatment benefits’, ‘cost’, ‘attenuate deterioration’, ‘education’, ‘medical management’, and ‘lifestyle modification’. The two qualitative approaches produced separate definitions (Table 3). There were two discrepancies observed between the inductively and deductively derived definitions: the inductive definition did not include medical optimisation nor education. As medical optimisation and education categories were reported rarely (n=5, 7% and n=3, 4%, respectively) across the 76 trials, these uncommon codes did not meet the proposed criteria for the inductive definition. Figure 2 represents the most frequently reported codes of each category across trials using the inductive method.

Table 2.

Identified inductive and deductive categories and their most reported codes using a summative content analysis approach.

| Category | Total category count and frequency∗ (n=76), n (%) | Most reported code(s) | Code count and frequency† (n=76), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inductive approach | |||

| Surgical period | 74 (97) | Preoperative | 37 (49) |

| Physical activity | 55 (72) | Exercise/exercise training | 25 (33) |

| Descriptor of prehabilitation | 32 (42) | Intervention | 16 (21) |

| Increase function | 28 (37) | Enhance/improve/augment functional capacity | 17 (22) |

| Withstand stress | 20 (26) | Withstand a stressful event/stressor of surgery | 11 (15) |

| Continuous (from diagnosis to treatment) | 18 (24) | Process | 12 (16) |

| Improve reserve | 18 (24) | Enhance/increase/optimise physiological reserve | 8 (11) |

| Optimise nutrition | 13 (17) | Nutrition/nutrition support | 6 (8) |

| Delivery modal | 13 (17) | Multimodal | 6 (8) |

| Improve outcomes | 11 (15) | Improve postoperative outcomes | 4 (5) |

| Respiratory training | 10 (13) | Pulmonary rehabilitation | 3 (4) |

| Inspiratory muscle training | 3 (4) | ||

| Psychological | 10 (13) | Anxiety-reducing strategies | 2 (3) |

| Psychological intervention | 2 (3) | ||

| Reduce stress and anxiety | 2 (3) | ||

| Recovery | 10 (13) | Facilitate recovery of functional capacity | 2 (3) |

| Rehabilitation | 7 (9) | Rehabilitation | 4 (5) |

| Medical optimisation | 5 (7) | Optimisation of medical conditions | 1 (1) |

| Smoking cessation | 1 (1) | ||

| Medical support | 1 (1) | ||

| Medical management | 1 (1) | ||

| Weight loss | 1 (1) | ||

| Treatment benefits | 4 (5) | Benefits/beneficial effect | 3 (4) |

| Attenuate deterioration | 4 (5) | Reduce patient disability | 1 (1) |

| Reduce the incidence or severity of future impairments | 1 (1) | ||

| Ameliorate the post-surgical physiologic deterioration | 1 (1) | ||

| Prevent or attenuate functional decline | 1 (1) | ||

| Behavioural support | 4 (5) | Behavioural support | 2 (3) |

| Education | 3 (4) | Education/education program | 3 (4) |

| Personalised to population | 3 (4) | For patients with lower fitness | 1 (1) |

| Varies according to context and the patient's needs | 1 (1) | ||

| Older patients with frailty | 1 (1) | ||

| Baseline function | 2 (3) | Establish a baseline functional level | 1 (1) |

| Identify impairments | 1 (1) | ||

| Cost | 1 (1) | Reduce financial burden on the health system | 1 (1) |

| Lifestyle modification | 1 (1) | Lifestyle modification | 1 (1) |

| Deductive approach | |||

| Purpose/goal | 104 (137) | Enhance functional capacity/aerobic capacity/physical fitness | 28 (37) |

| Improve postoperative outcomes | 17 (22) | ||

| Combat surgical stressors | 15 (20) | ||

| Intervention type | 77 (101) | Exercise/physical activity | 42 (55) |

| Nutrition | 12 (16) | ||

| Psychological | 7 (9) | ||

| Medical optimisation | 5 (7) | ||

| Education | 3 (4) | ||

| Timing | 51 (67) | Before surgery/preoperative | 47 (62) |

| Descriptor | 47 (62) | Program | 14 (18) |

| Process | 12 (16) | ||

| Intervention | 8 (11) | ||

| Target population | 4 (5) | Patients with lower preoperative fitness | 1 (1) |

| Older patients with frailty | 1 (1) | ||

| Individualised to patients' needs and context | 1 (1) | ||

| Surgical patients | 1 (1) | ||

∗Total category count and frequency: number of times codes within a specific category was reported across 76 trials. †Total code count and frequency: number of times a code was reported across 76 trials; studies may report multiple codes in one category.

Table 3.

Surgical prehabilitation definitions using inductive and deductive qualitative approaches. TiDER: Template for Intervention Description and Replication.

| Method | Definition |

|---|---|

| Inductive qualitative approach using the most common keywords | ‘Prehabilitation is a process from diagnosis to treatment that consists of an unimodal or multimodal preoperative intervention including exercise, nutrition, psychological strategies and/or respiratory training, and aims to enhance functional capacity and physiological reserve to allow patients to withstand surgical stressors, improve postoperative outcomes and facilitate recovery.’ |

| Deductive qualitative approach using the TiDER checklist | ‘Prehabilitation can be defined as a program delivered prior to surgery that may consist of a number of interventions including exercise therapy, nutritional optimisation, psychological strategies, respiratory training, medical optimisation, and education, and aims to enhance functional capacity and physiological reserve to allow a patient to withstand surgical stressors and improve postoperative outcomes.’ |

| Proposed common definition | ‘Prehabilitation is a process from diagnosis to surgery, consisting of one or more preoperative interventions of exercise, nutrition, psychological strategies and respiratory training, that aims to enhance functional capacity and physiological reserve to allow patients to withstand surgical stressors, improve postoperative outcomes, and facilitate recovery.’ |

Fig 2.

Word cloud using an inductive qualitative approach to define surgical prehabilitation. The scaling of each code is proportional to the number of times it was reported across the 76 trials included.

Discussion

Need for a standardised definition

Currently, there is no standardised, universally accepted definition for surgical prehabilitation. Harmonised definitions in clinical research give rise to more robust evidence by facilitating the use of consistent designs, interventions, and reported outcomes, which can improve the pooling of data for future meta-analysis, leading to higher levels of evidence certainty.11 In fact, scoping reviews of surgical prehabilitation intervention15 and outcome reporting16 reveal significant heterogeneity, and this lack of consensus has impeded the ability to draw strong conclusions regarding the effectiveness of surgical prehabilitation.11 Given that prehabilitation is a complex intervention99, involving different components, targeted behaviours, and levels of provider expertise, consolidating a definition is an important step to inform standardised and rigorous research. Ultimately, the adoption of a common intervention definition, in addition to a core outcome set, could enhance the ability to develop, evaluate, and implement preoperative interventions that support optimal patient recovery after surgery.11 As a first step towards standardisation, this scoping review proposes a common extensional definition of surgical prehabilitation, developed by qualitatively triangulating and synthesising prehabilitation definitions across 76 primary RCTs.

Components of a common prehabilitation definition

Using both inductive and deductive approaches, we identified consistent surgical prehabilitation components across 76 trials, including timing (before surgery), modalities (exercise, nutrition, psychological, and respiratory training), and objectives (enhancing functional capacity and physiological reserve to improve outcomes and recovery), which inform our proposed common definition. Given the heterogeneity of the included study interventions and definitions, our proposed definition should be seen as an initial step towards the foundational work required to finalise a widely accepted definition that can be adopted internationally by the multidisciplinary and intersectoral field of prehabilitation.

We acknowledge that uncertainty and possible controversy remain about whether medical optimisation100,101 and education are components of surgical prehabilitation interventions. Our findings suggest that these components are not common interventions in prehabilitation. That said, the modalities included in our proposed definition might be enhanced by medical optimisation (e.g. anaemia correction) and inherently involve modality-specific education102 (i.e. education or counselling related to anxiety management, nutrition, exercise, and breathing techniques). The exclusion of ‘medical optimisation’ and broad ‘education’ across trials of prehabilitation, and therefore our proposed definition, might reflect the distinct nature of prehabilitation modalities. For example, medical optimisation (and the related concept of medical clearance) and preoperative education (e.g. procedure-specific logistics, expectations of surgery, carbohydrate loading) are well-established and long-standing practices, often led by perioperative care clinicians (anaesthesiologists, surgeons, internal medicine specialists, nurses, or others) as part of standard care, independent of prehabilitation.103 Conceptually, the prehabilitation modalities included in our definition would be expected to supplement and occur in parallel with medical optimisation and preoperative education. Prehabilitation interventions focus primarily on healthcare professionals supporting change in patient behaviours with the specific purpose of building physiological reserve and psychological resilience before surgery. In contrast, surgery-specific medical optimisation focuses on healthcare professional-supported optimisation of long-term health conditions primarily involving pharmacological interventions and devices (e.g. diabetes mellitus control, blood pressure management, anaemia management, sleep apnoea diagnosis and management).103 Furthermore, medical optimisation is embedded within Enhanced Recovery After Surgery programmes.104 Education is also one of the pillars of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery programs, which are well-established, evidence-based perioperative care improvement interventions that are already embedded within surgical pathways.104,105 These education programmes provide information about the planned procedure, pain management, early mobilisation, and establishment of oral intake. The infrequent reporting of education and medical optimisation in prehabilitation trials may thus reflect that these interventions are already viewed as part of the routine perioperative pathway in many centres. Prehabilitation, by our definition, is complementary to the existing surgical preparation pathways inclusive of risk stratification, shared decision-making, medical optimisation, and patient education, and aims to confer additional benefits by improving both patient experience and postoperative outcomes.106 It is possible that sites lacking standardised medical optimisation and patient education services were more inclined to include these components in their definition of prehabilitation. Ultimately, broad collaboration between patients, clinicians, researchers, and health system leaders internationally, informed by robust knowledge synthesis, will be required to achieve a widely accepted definition.

Limitations and future directions

The common definition produced from this scoping review is not without limitations. Firstly, the definition has been generated using only published definitions (in English and French), meaning it is limited to commonly reported components of surgical prehabilitation trials, which does not necessarily reflect validity nor consensus. Secondly, we must acknowledge that the cutoff of 10 used to denote commonality in the inductive summative content analysis was arbitrary and led to the exclusion of two modalities that remained in the deductive approach: medical optimisation (n=5) and education (n=3). A consultation exercise is required to achieve consensus in support of the inclusion or exclusion of medical optimisation and broad education as part of surgical prehabilitation. Thirdly, as observed in Figure 2, the consolidated definition is limited by the historical perspective of prehabilitation that has been predominantly described as ‘preoperative exercise’ even though multimodal models in cancer and surgery have expanded beyond exercise therapy alone.107 Fourthly, the trials that reported explicit definitions (n=42, 55%) were mainly from abdominal, orthopaedic, and spinal specialities; therefore, this common definition might not reflect the priorities of other surgery types. Given that the goal of this scoping review was to describe how surgical prehabilitation is currently being defined, we did not additionally consult a group of experts in the prehabilitation field for further input and consensus. We suggest that the next step is to consult international stakeholders and experts in the field to ensure the development of a comprehensive and globally accepted definition.

Conclusions

There are many distinctive published definitions for surgical prehabilitation. This scoping review consolidated the available literature to suggest a common definition using a qualitative triangulation approach. The proposed common definition is the first step towards standardisation, which is needed to guide future high-quality RCTs and advance the prehabilitation field.

Authors’ contributions

Study design, analysis of the data, and writing of the manuscript (equal contribution): CFG, NB, LD, CG

Creation of tables and figures: CFG

Study design, interpretation of data, and meaningfully revised the final manuscript and provided expertise in the fields of prehabilitation and perioperative medicine throughout: All authors

Acknowledgements

We thank Genevieve Gore, Liaison Librarian, Schulich Library of Physical Sciences, Life Sciences, and Engineering, McGill University (Montréal, QC, Canada), for her assistance with developing and conducting the search strategy for this scoping review.

Declaration of interest

CG has received honoraria for giving educational talks sponsored by Abbott Nutrition, Nestle Nutrition, and Fresenius Kabi, which were unrelated to this paper.

Handling Editor: Hugh C Hemmings Jr

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2024.02.035.

Contributor Information

Linda Denehy, Email: l.denehy@unimelb.edu.au.

Chelsia Gillis, Email: chelsia.gillis@mcgill.ca.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Prehabilitation, rehabilitation, and revocation in the army. BMJ. 1946;1:192–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiner P., Man A., Weiner M., et al. The effect of incentive spirometry and inspiratory muscle training on pulmonary function after lung resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113:552–557. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arthur H.M., Daniels C., McKelvie R., Hirsh J., Rush B. Effect of a preoperative intervention on preoperative and postoperative outcomes in low-risk patients awaiting elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:253–262. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-4-200008150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaggers J.R., Simpson C.D., Frost K.L., et al. Prehabilitation before knee arthroplasty increases postsurgical function: a case study. J Strength Cond Res. 2007;21:632–634. doi: 10.1519/R-19465.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielsen P.R., Jorgensen L.D., Dahl B., Pedersen T., Tonnesen H. Prehabilitation and early rehabilitation after spinal surgery: randomized clinical trial. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24:137–148. doi: 10.1177/0269215509347432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li C., Carli F., Lee L., et al. Impact of a trimodal prehabilitation program on functional recovery after colorectal cancer surgery: a pilot study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1072–1082. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayo N.E., Feldman L., Scott S., et al. Impact of preoperative change in physical function on postoperative recovery: argument supporting prehabilitation for colorectal surgery. Surgery. 2011;150:505–514. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morano M.T., Araújo A., Nascimento F.B., et al. Preoperative pulmonary rehabilitation versus chest physical therapy in patients undergoing lung cancer resection: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.08.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inoue J., Ono R., Makiura D., et al. Prevention of postoperative pulmonary complications through intensive preoperative respiratory rehabilitation in patients with esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:68–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silver J.K., Baima J. Cancer prehabilitation: an opportunity to decrease treatment-related morbidity, increase cancer treatment options, and improve physical and psychological health outcomes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;92:715–727. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31829b4afe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McIsaac D.I., Gill M., Boland L., et al. Prehabilitation in adult patients undergoing surgery: an umbrella review of systematic reviews. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128:244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arksey H., O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engel D., Testa G., McIsaac D., et al. Reporting quality of randomized controlled trials in prehabilitation: a scoping review. Perioper Med. 2023;12:48. doi: 10.1186/s13741-023-00338-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleurent-Grégoire C., Burgess N., Denehy L., et al. Outcomes reported in randomised trials of surgical prehabilitation: a scoping review. Br J Anaesth. 2024 Apr 2 doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2024.01.046. S0007-0912(24)00103-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheede-Bergdahl C., Minnella E.M., Carli F. Multi-modal prehabilitation: addressing the why, when, what, how, who and where next? Anaesthesia. 2019;74:20–26. doi: 10.1111/anae.14505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luther A., Gabriel J., Watson R.P., Francis N.K. The impact of total body prehabilitation on post-operative outcomes after major abdominal surgery: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2018;42:2781–2791. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4569-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillis C., Buhler K., Bresee L., et al. Effects of nutritional prehabilitation, with and without exercise, on outcomes of patients who undergo colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:391–410.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh H.-F., Shannon S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleinheksel A.J., Rockich-Winston N., Tawfik H., Wyatt T.R. Demystifying content analysis. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84:7113. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter N., Bryant-Lukosius D., DiCenso A., Blythe J., Neville A.J. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41:545–547. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.545-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffmann T.C., Glasziou P.P., Boutron I., et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ostertag G. In: The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Zalta E.N., editor. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University; 2020. Emily Elizabeth Constance Jones. Fall 2020 Edn. [Google Scholar]

- 25.An J., Ryu H.K., Lyu S.J., Yi H.J., Lee B.H. Effects of preoperative telerehabilitation on muscle strength, range of motion, and functional outcomes in candidates for total knee arthroplasty: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2021;18:6071. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18116071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Argunova Y., Belik E., Gruzdeva O., Ivanov S., Pomeshkina S., Barbarash O. Effects of physical prehabilitation on the dynamics of the markers of endothelial function in patients undergoing elective coronary bypass surgery. J Pers Med. 2022;12:471. doi: 10.3390/jpm12030471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ausania F., Senra P., Melendez R., Caballeiro R., Ouvina R., Casal-Nunez E. Prehabilitation in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2019;111:603–608. doi: 10.17235/reed.2019.6182/2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barberan-Garcia A., Ubre M., Roca J., et al. Personalised prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery: a randomized blinded controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2018;267:50–56. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berkel A.E.M., Bongers B.C., Kotte H., et al. Effects of community-based exercise prehabilitation for patients scheduled for colorectal surgery with high risk for postoperative complications: results of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2022;275:e299–e306. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blackwell J.E.M., Doleman B., Boereboom C.L., et al. High-intensity interval training produces a significant improvement in fitness in less than 31 days before surgery for urological cancer: a randomised control trial. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020;23:696–704. doi: 10.1038/s41391-020-0219-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bousquet-Dion G., Awasthi R., Loiselle S.E., et al. Evaluation of supervised multimodal prehabilitation programme in cancer patients undergoing colorectal resection: a randomized control trial. Acta Oncol. 2018;57:849–859. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1423180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown K., Loprinzi P.D., Brosky J.A., Topp R. Prehabilitation influences exercise-related psychological constructs such as self-efficacy and outcome expectations to exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;28:201–209. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318295614a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown K., Topp R., Brosky J.A., Lajoie A.S. Prehabilitation and quality of life three months after total knee arthroplasty: a pilot study. Percept Mot Skills. 2012;115:765–774. doi: 10.2466/15.06.10.PMS.115.6.765-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calatayud J., Casana J., Ezzatvar Y., Jakobsen M.D., Sundstrup E., Andersen L.L. High-intensity preoperative training improves physical and functional recovery in the early post-operative periods after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:2864–2872. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-3985-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carli F., Bousquet-Dion G., Awasthi R., et al. Effect of multimodal prehabilitation vs postoperative rehabilitation on 30-day postoperative complications for frail patients undergoing resection of colorectal cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:233–242. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carli F., Charlebois P., Stein B., et al. Randomized clinical trial of prehabilitation in colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1187–1197. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cavill S., McKenzie K., Munro A., et al. The effect of prehabilitation on the range of motion and functional outcomes in patients following the total knee or hip arthroplasty: a pilot randomized trial. Physiother Theory Pract. 2016;32:262–270. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2016.1138174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunne D.F., Jack S., Jones R.P., et al. Randomized clinical trial of prehabilitation before planned liver resection. Br J Surg. 2016;103:504–512. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferreira V., Lawson C., Carli F., Scheede-Bergdahl C., Chevalier S. Feasibility of a novel mixed-nutrient supplement in a multimodal prehabilitation intervention for lung cancer patients awaiting surgery: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Int J Surg. 2021;93 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.106079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferreira V., Minnella E.M., Awasthi R., et al. Multimodal prehabilitation for lung cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;112:1600–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fulop A., Lakatos L., Susztak N., Szijarto A., Banky B. The effect of trimodal prehabilitation on the physical and psychological health of patients undergoing colorectal surgery: a randomised clinical trial. Anaesthesia. 2021;76:82–90. doi: 10.1111/anae.15215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gillis C., Li C., Lee L., et al. Prehabilitation versus rehabilitation: a randomized control trial in patients undergoing colorectal resection for cancer. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:937–947. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gillis C., Loiselle S.E., Fiore J.F., Jr., et al. Prehabilitation with whey protein supplementation on perioperative functional exercise capacity in patients undergoing colorectal resection for cancer: a pilot double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116:802–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gloor S., Misirlic M., Frei-Lanter C., et al. Prehabilitation in patients undergoing colorectal surgery fails to confer reduction in overall morbidity: results of a single-center, blinded, randomized controlled trial. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg. 2022;407:897–907. doi: 10.1007/s00423-022-02449-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Granicher P., Stoggl T., Fucentese S.F., Adelsberger R., Swanenburg J. Preoperative exercise in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch Physiother. 2020;10:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s40945-020-00085-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grant L.F., Cooper D.J., Conroy J.L. The HAPI ‘Hip Arthroscopy Pre-habilitation Intervention’ study: does pre-habilitation affect outcomes in patients undergoing hip arthroscopy for femoro-acetabular impingement? J Hip Preserv Surg. 2017;4:85–92. doi: 10.1093/jhps/hnw046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gravier F.E., Smondack P., Boujibar F., et al. Prehabilitation sessions can be provided more frequently in a shortened regimen with similar or better efficacy in people with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2022;68:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2021.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang J., Lai Y., Zhou X., et al. Short-term high-intensity rehabilitation in radically treated lung cancer: a three-armed randomized controlled trial. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:1919–1929. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.06.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang S.W., Chen P.H., Chou Y.H. Effects of a preoperative simplified home rehabilitation education program on length of stay of total knee arthroplasty patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Humeidan M.L., Reyes J.C., Mavarez-Martinez A., et al. Effect of cognitive prehabilitation on the incidence of postoperative delirium among older adults undergoing major noncardiac surgery: the Neurobics randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:148–156. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.4371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jahic D., Omerovic D., Tanovic A.T., Dzankovic F., Campara M.T. The effect of prehabilitation on postoperative outcome in patients following primary total knee arthroplasty. Medicinski Arhiv. 2018;72:439–443. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2018.72.439-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jensen B.T., Petersen A.K., Jensen J.B., Laustsen S., Borre M. Efficacy of a multiprofessional rehabilitation programme in radical cystectomy pathways: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Scand J Urol. 2015;49:133–141. doi: 10.3109/21681805.2014.967810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim D.J., Mayo N.E., Carli F., Montgomery D.L., Zavorsky G.S. Responsive measures to prehabilitation in patients undergoing bowel resection surgery. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2009;217:109–115. doi: 10.1620/tjem.217.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim S., Hsu F.C., Groban L., Williamson J., Messier S. A pilot study of aquatic prehabilitation in adults with knee osteoarthritis undergoing total knee arthroplasty – short term outcome. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22:388. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04253-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lai Y., Huang J., Yang M., Su J., Liu J., Che G. Seven-day intensive preoperative rehabilitation for elderly patients with lung cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Surg Res. 2017;209:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liang M.K., Bernardi K., Holihan J.L., et al. Modifying risks in ventral hernia patients with prehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2018;268:674–680. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Licker M., Karenovics W., Diaper J., et al. Short-term preoperative high-intensity interval training in patients awaiting lung cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.09.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lindbäck Y., Tropp H., Enthoven P., Abbott A., Öberg B. PREPARE: presurgery physiotherapy for patients with degenerative lumbar spine disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Spine J. 2018;18:1347–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu Z., Qiu T., Pei L., et al. Two-week multimodal prehabilitation program improves perioperative functional capability in patients undergoing thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:840–849. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.López-Rodríguez-Arias F., Sánchez-Guillén L., Aranaz-Ostáriz V., et al. Effect of home-based prehabilitation in an enhanced recovery after surgery program for patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:7785–7791. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06343-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lotzke H., Brisby H., Gutke A., et al. A person-centered prehabilitation program based on cognitive-behavioral physical therapy for patients scheduled for lumbar fusion surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2019;99:1069–1088. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzz020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marchand A.-A., Houle M., O’Shaughnessy J., Châtillon C.-É., Cantin V., Descarreaux M. Effectiveness of an exercise-based prehabilitation program for patients awaiting surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: a randomized clinical trial. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90537-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eil M.S.M., Sharifudin M.A., Shokri A.A., Ab Rahman S. Preoperative physiotherapy and short-term functional outcomes of primary total knee arthroplasty. Singapore Med J. 2016;57:138. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2016055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matassi F., Duerinckx J., Vandenneucker H., Bellemans J. Range of motion after total knee arthroplasty: the effect of a preoperative home exercise program. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22:703–709. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2349-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McKay C., Prapavessis H., Doherty T. The effect of a prehabilitation exercise program on quadriceps strength for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled pilot study. PM R. 2012;4:647–656. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Minnella E.M., Awasthi R., Bousquet-Dion G., et al. Multimodal prehabilitation to enhance functional capacity following radical cystectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Urol Focus. 2021;7:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Minnella E.M., Awasthi R., Loiselle S.E., Agnihotram R.V., Ferri L.E., Carli F. Effect of exercise and nutrition prehabilitation on functional capacity in esophagogastric cancer surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:1081–1089. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Minnella E.M., Ferreira V., Awasthi R., et al. Effect of two different pre-operative exercise training regimens before colorectal surgery on functional capacity: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2020;37:969–978. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nguyen C., Boutron I., Roren A., et al. Effect of prehabilitation before total knee replacement for knee osteoarthritis on functional outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Northgraves M.J., Arunachalam L., Madden L.A., et al. Feasibility of a novel exercise prehabilitation programme in patients scheduled for elective colorectal surgery: a feasibility randomised controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:3197–3206. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05098-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.O’Gara B.P., Mueller A., Gasangwa D.V.I., et al. Prevention of early postoperative decline: a randomized, controlled feasibility trial of perioperative cognitive training. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:586–595. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Onerup A., Andersson J., Angenete E., et al. Effect of short-term homebased pre- and postoperative exercise on recovery after colorectal cancer surgery (PHYSSURG-C): a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2022;275:448–455. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peng L.H., Wang W.J., Chen J., Jin J.Y., Min S., Qin P.P. Implementation of the pre-operative rehabilitation recovery protocol and its effect on the quality of recovery after colorectal surgeries. Chin Med J. 2021;134:2865–2873. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Santa Mina D., Hilton W.J., Matthew A.G., et al. Prehabilitation for radical prostatectomy: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Surg Oncol. 2018;27:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Satoto H.H., Paramitha A., Barata S.H., et al. Effect of preoperative inspiratory muscle training on right ventricular systolic function in patients after heart valve replacement surgery. Bali Med J. 2021;10:340–346. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sawatzky J.A., Kehler D.S., Ready A.E., et al. Prehabilitation program for elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients: a pilot randomized controlled study. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28:648–657. doi: 10.1177/0269215513516475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sebio Garcia R., Yanez-Brage M.I., Gimenez Moolhuyzen E., Salorio Riobo M., Lista Paz A., Borro Mate J.M. Preoperative exercise training prevents functional decline after lung resection surgery: a randomized, single-blind controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:1057–1067. doi: 10.1177/0269215516684179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shaarani S.R., O'Hare C., Quinn A., Moyna N., Moran R., O'Byrne J.M. Effect of prehabilitation on the outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:2117–2127. doi: 10.1177/0363546513493594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Steinmetz C., Bjarnason-Wehrens B., Baumgarten H., Walther T., Mengden T., Walther C. Prehabilitation in patients awaiting elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery – effects on functional capacity and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2020;34:1256–1267. doi: 10.1177/0269215520933950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tenconi S., Mainini C., Rapicetta C., et al. Rehabilitation for lung cancer patients undergoing surgery: results of the PUREAIR randomized trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2021;57:1002–1011. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.21.06789-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Topp R., Swank A.M., Quesada P.M., Nyl J., Malkani A. The effect of prehabilitation exercise on strength and functioning after total knee arthroplasty. PM R. 2009;1:729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vagvolgyi A., Rozgonyi Z., Kerti M., Agathou G., Vadasz P., Varga J. Effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation and correlations in between functional parameters, extent of thoracic surgery and severity of post-operative complications: randomized clinical trial. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:3519–3531. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.05.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.IJmker-Hemink V.E., Wanten G.J.A., de Nes L.C.F., van den Berg M.G.A. Effect of a preoperative home-delivered, protein-rich meal service to improve protein intake in surgical patients: a randomized controlled trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2021;45:479–489. doi: 10.1002/jpen.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Waller E., Sutton P., Rahman S., Allen J., Saxton J., Aziz O. Prehabilitation with wearables versus standard of care before major abdominal cancer surgery: a randomised controlled pilot study (trial registration: NCT04047524) Surg Endosc. 2022;2:1008–1017. doi: 10.1007/s00464-021-08365-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang X., Che G., Liu L. A short-term high-intensive pattern of preoperative rehabilitation better suits surgical lung cancer patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;25 ivx280-037. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Woodfield J.C., Clifford K., Wilson G.A., Munro F., Baldi J.C. Short-term high-intensity interval training improves fitness before surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2022;28:28. doi: 10.1111/sms.14130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yamana I., Takeno S., Hashimoto T., et al. Randomized controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of a preoperative respiratory rehabilitation program to prevent postoperative pulmonary complications after esophagectomy. Dig Surg. 2015;32:331–337. doi: 10.1159/000434758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Furon Y., Dang Van S., Blanchard S., Saulnier P., Baufreton C. Effects of high-intensity inspiratory muscle training on systemic inflammatory response in cardiac surgery – a randomized clinical trial. Physiother Theory Pract. 2024;40:778–788. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2022.2163212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Franz A., Ji S., Bittersohl B., Zilkens C., Behringer M. Impact of a six-week prehabilitation with blood-flow restriction training on pre-and postoperative skeletal muscle mass and strength in patients receiving primary total knee arthroplasty. Front Physiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.881484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Heiman J., Onerup A., Wessman C., Haglind E., Olofsson Bagge R. Recovery after breast cancer surgery following recommended pre and postoperative physical activity:(PhysSURG-B) randomized clinical trial. Br J Surg. 2021;108:32–39. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znaa007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Milios J.E., Ackland T.R., Green D.J. Pelvic floor muscle training in radical prostatectomy: a randomized controlled trial of the impacts on pelvic floor muscle function and urinary incontinence. BMC Urol. 2019;19:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12894-019-0546-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rampam S., Sadiq H., Patel J., et al. Supervised preoperative walking on increasing early postoperative stamina and mobility in older adults with frailty traits: a pilot and feasibility study. Health Sci Rep. 2022;5 doi: 10.1002/hsr2.738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Molenaar C.J.L., Minnella E.M., Coca-Martinez M., et al. Effect of multimodal prehabilitation on reducing postoperative complications and enhancing functional capacity following colorectal cancer surgery: the PREHAB randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2023;158:572–581. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2023.0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McIsaac D.I., Hladkowicz E., Bryson G.L., et al. Home-based prehabilitation with exercise to improve postoperative recovery for older adults with frailty having cancer surgery: the PREHAB randomised clinical trial. Br J Anaesth. 2022;129:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2022.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.D’Lima D.D., Colwell C.W., Jr., Morris B.A., Hardwick M.E., Kozin F. The effect of preoperative exercise on total knee replacement outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996:174–182. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199605000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rooks D.S., Huang J., Bierbaum B.E., et al. Effect of preoperative exercise on measures of functional status in men and women undergoing total hip and knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2006;55:700–708. doi: 10.1002/art.22223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Beaupre L.A., Lier D., Davies D.M., Johnston D.B.C. The effect of a preoperative exercise and education program on functional recovery, health related quality of life, and health service utilization following primary total knee arthroplasty. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1166–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hulzebos E.H., Helders P.J., Favié N.J., De Bie R.A., Brutel de la Riviere A., Van Meeteren N.L. Preoperative intensive inspiratory muscle training to prevent postoperative pulmonary complications in high-risk patients undergoing CABG surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2006;296:1851–1857. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Skivington K., Matthews L., Simpson S.A., et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374:n2061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Beckerleg W., Kobewka D., Wijeysundera D.N., Sood M.M., McIsaac D.I. Association of preoperative medical consultation with reduction in adverse postoperative outcomes and use of processes of care among residents of Ontario, Canada. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183:470–478. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wijeysundera D.N., Austin P.C., Beattie W.S., Hux J.E., Laupacis A. Outcomes and processes of care related to preoperative medical consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1365–1374. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Boden I., Skinner E.H., Browning L., et al. Preoperative physiotherapy for the prevention of respiratory complications after upper abdominal surgery: pragmatic, double blinded, multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2018;360 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Riggs K., Segal J. What is the rationale for preoperative medical evaluations? A closer look at surgical risk and common terminology. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117:681–684. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ljungqvist O., Scott M., Fearon K.C. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:292–298. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ronco M., Iona L., Fabbro C., Bulfone G., Palese A. Patient education outcomes in surgery: a systematic review from 2004 to 2010. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2012;10:309–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2012.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gillis C., Ljungqvist O., Carli F. Prehabilitation, enhanced recovery after surgery, or both? A narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128:434–448. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Macmillan Cancer Support Principles and guidance for prehabilitation. 2019. https://www.macmillan.org.uk/healthcare-professionals/news-and-resources/guides/principles-and-guidance-for-prehabilitation Available from:

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.