Abstract

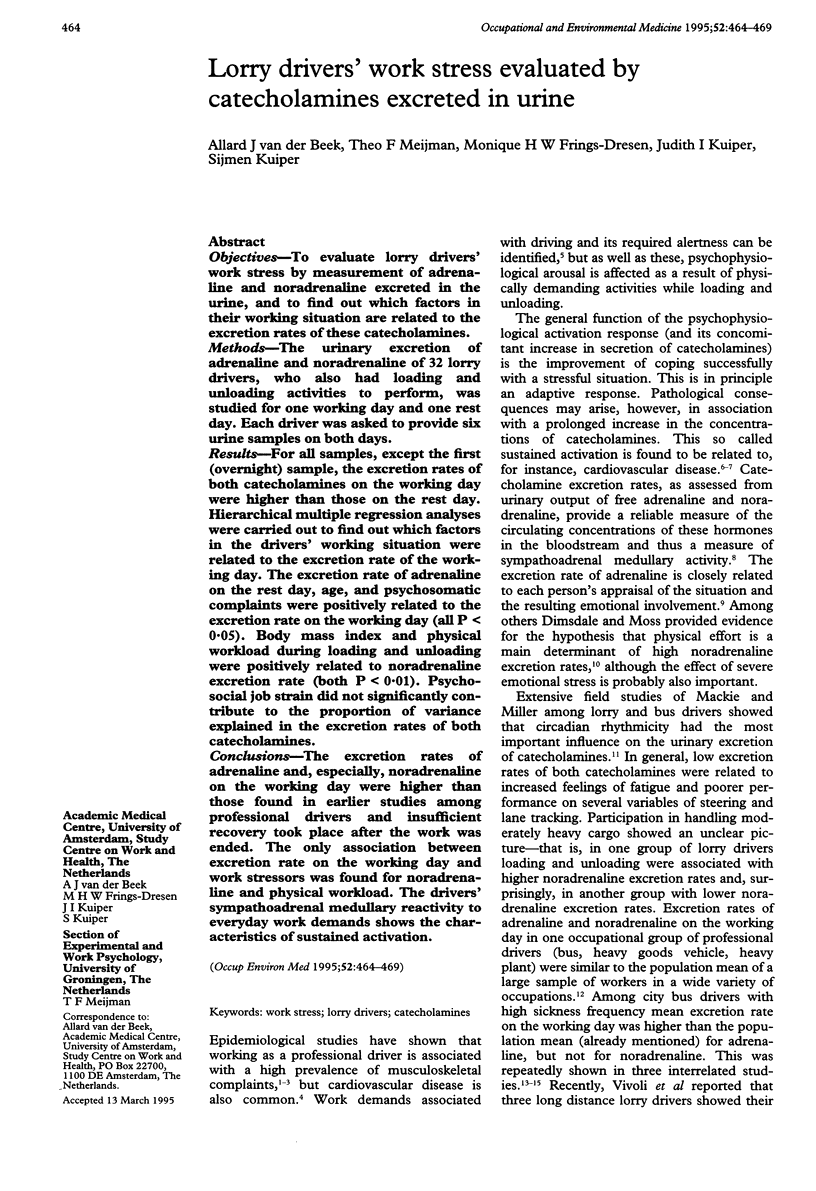

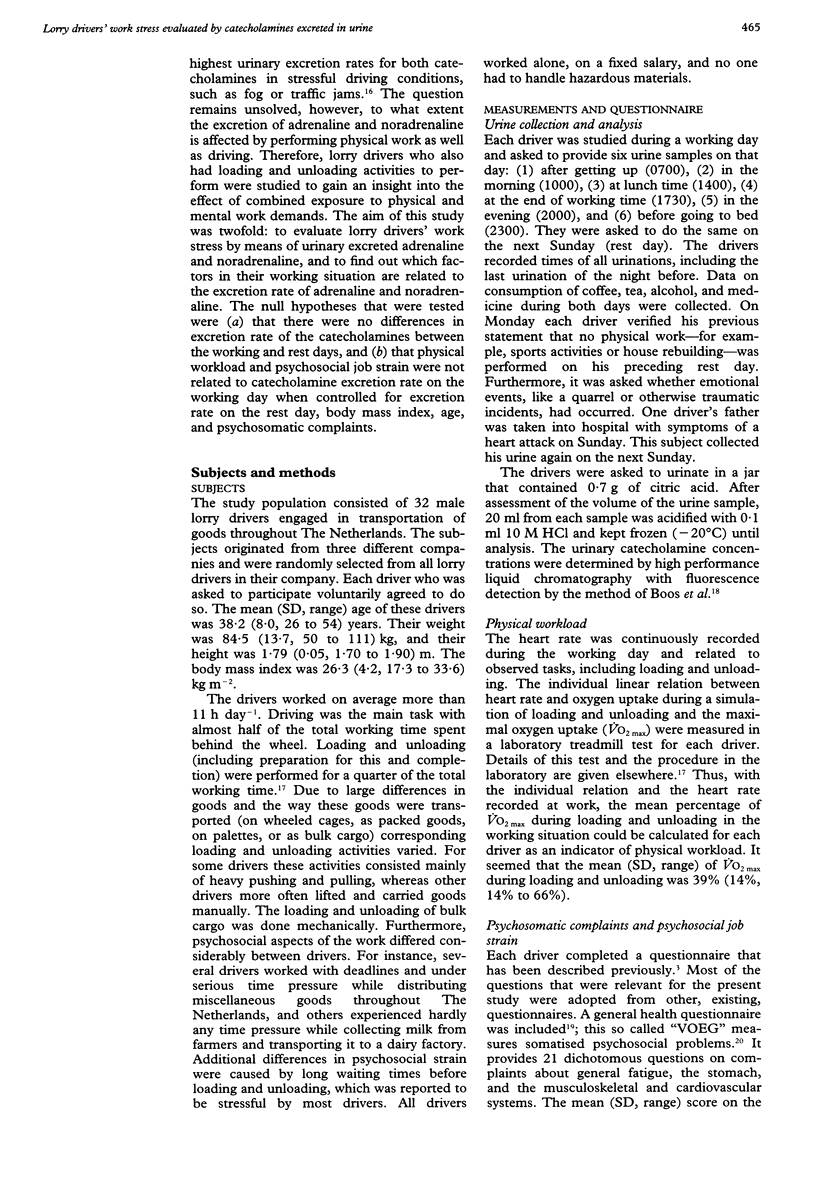

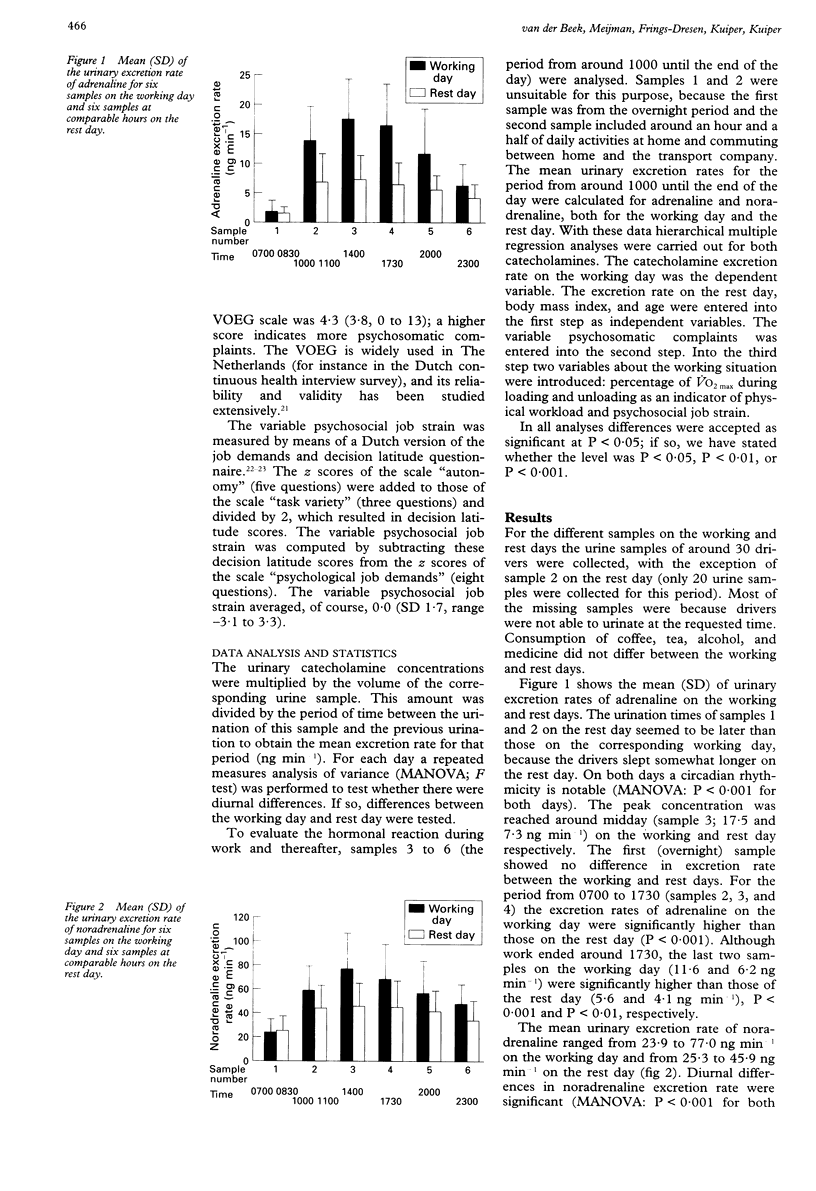

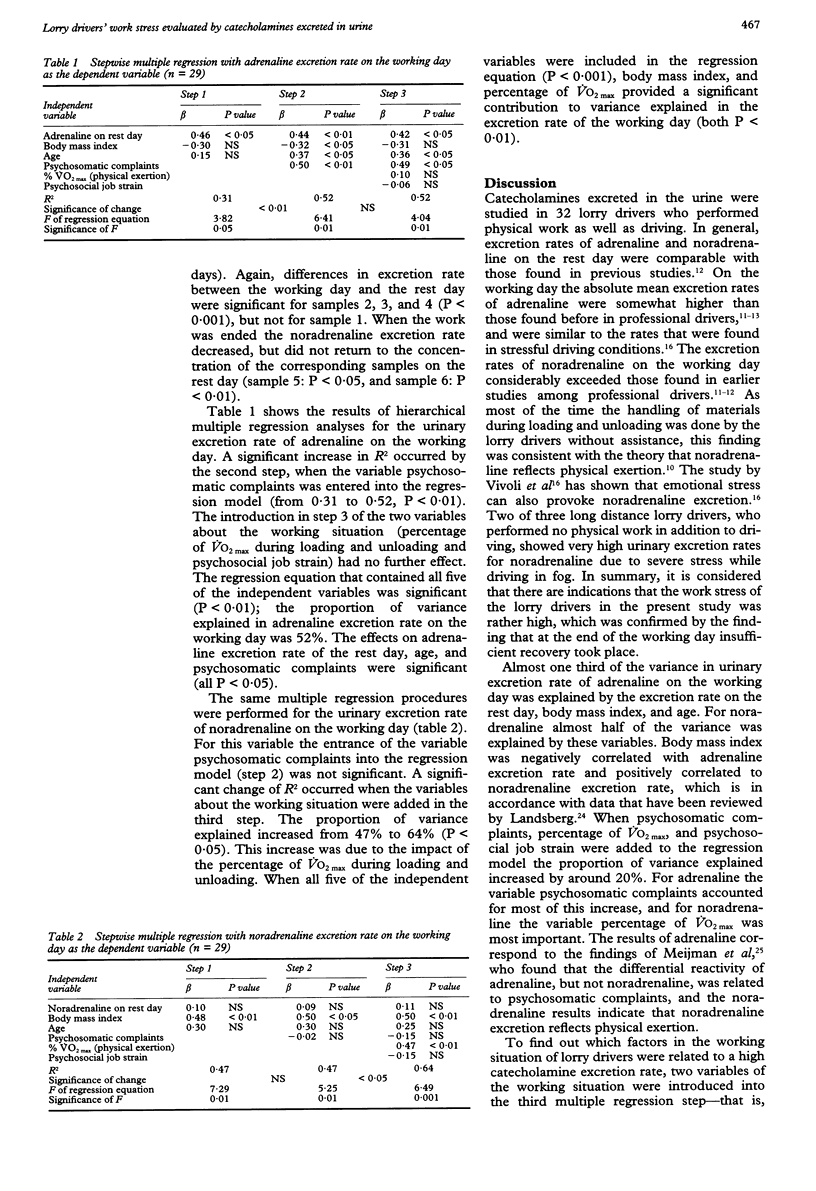

OBJECTIVES--To evaluate lorry drivers' work stress by measurement of adrenaline and noradrenaline excreted in the urine, and to find out which factors in their working situation are related to the excretion rates of these catecholamines. METHODS--The urinary excretion of adrenaline and noradrenaline of 32 lorry drivers, who also had loading and unloading activities to perform, was studied for one working day and one rest day. Each driver was asked to provide six urine samples on both days. RESULTS--For all samples, except the first (overnight) sample, the excretion rates of both catecholamines on the working day were higher than those on the rest day. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were carried out to find out which factors in the drivers' working situation were related to the excretion rate of the working day. The excretion rate of adrenaline on the rest day, age, and psychosomatic complaints were positively related to the excretion rate on the working day (all P < 0.05). Body mass index and physical workload during loading and unloading were positively related to noradrenaline excretion rate (both P < 0.01). Psychosocial job strain did not significantly contribute to the proportion of variance explained in the excretion rates of both catecholamines. CONCLUSIONS--The excretion rates of adrenaline and, especially, noradrenaline on the working day were higher than those found in earlier studies among professional drivers and insufficient recovery took place after the work was ended. The only association between excretion rate on the working day and work stressors was found for noradrenaline and physical workload. The drivers' sympathoadrenal medullary reactivity to everyday work demands shows the characteristics of sustained activation.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Backman A. L. Health survey of professional drivers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1983 Feb;9(1):30–35. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkić K., Savić C., Theorell T., Rakić L., Ercegovac D., Djordjević M. Mechanisms of cardiac risk among professional drivers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1994 Apr;20(2):73–86. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienstbier R. A. Arousal and physiological toughness: implications for mental and physical health. Psychol Rev. 1989 Jan;96(1):84–100. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.96.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienstbier R. A. Behavioral correlates of sympathoadrenal reactivity: the toughness model. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991 Jul;23(7):846–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimsdale J. E., Moss J. Plasma catecholamines in stress and exercise. JAMA. 1980 Jan 25;243(4):340–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedberg G. E. The period prevalence of musculoskeletal complaints among Swedish professional drivers. Scand J Soc Med. 1988;16(1):5–13. doi: 10.1177/140349488801600102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner D. A., Reynolds V., Harrison G. A. Catecholamine excretion rates and occupation. Ergonomics. 1980 Mar;23(3):237–246. doi: 10.1080/00140138008924737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson G., Aronsson G., Lindström B. O. Social psychological and neuroendocrine stress reactions in highly mechanised work. Ergonomics. 1978 Aug;21(8):583–599. doi: 10.1080/00140137808931761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsberg L. Pathophysiology of obesity-related hypertension: role of insulin and the sympathetic nervous system. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1994;23 (Suppl 1):S1–S8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejman T. F., Mulders H. P., Kompier M. A., van Dormolen M. Individual differences in adrenaline/noradrenaline reactivity and self-perceived health status. Z Gesamte Hyg. 1990 Aug;36(8):413–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moleman P., Tulen J. H., Blankestijn P. J., Man in 't Veld A. J., Boomsma F. Urinary excretion of catecholamines and their metabolites in relation to circulating catecholamines. Six-hour infusion of epinephrine and norepinephrine in healthy volunteers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992 Jul;49(7):568–572. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820070062009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulders H. P., Meijman T. F., O'Hanlon J. F., Mulder G. Differential psychophysiological reactivity of city bus drivers. Ergonomics. 1982 Nov;25(11):1003–1011. doi: 10.1080/00140138208925061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaubroeck J., Ganster D. C. Chronic demands and responsivity to challenge. J Appl Psychol. 1993 Feb;78(1):73–85. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivoli G., Bergomi M., Rovesti S., Carrozzi G., Vezzosi A. Biochemical and haemodynamic indicators of stress in truck drivers. Ergonomics. 1993 Sep;36(9):1089–1097. doi: 10.1080/00140139308967980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]