Abstract

The ability of the pleotropic, proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6) to affect the replication, latency, and reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) in cell culture and in IL-6 knockout (KO) mice was studied. In initial studies, we found no effect of exogenous IL-6, monoclonal antibodies to IL-6, or monoclonal antibody to the IL-6 coreceptor, gp130, on HSV-1 replication in vitro by plaque assay or reactivation ex vivo by explant cocultivation of latently infected murine trigeminal ganglia (TG). Compared with the wild-type (WT) mice, the IL-6 KO mice were less able to survive an ocular challenge with 105 PFU of HSV-1 (McKrae) (40% survival of WT and 7% survival KO mice; P = 0.01). There was a sixfold higher 50% lethal dose of HSV-1 in WT than IL-6 KO mice (1.7 × 104 and 2.7 × 103 PFU, respectively). No differences were observed in titers of virus recovered from the eyes, TG, or brains or in the rates of virus reactivation by explant cocultivation of TG from latently infected WT or KO mice. Exposure of latently infected mice to UV light resulted in comparable rates of reactivation and in the proportions of WT and KO animals experiencing reactivation. Moreover, quantitative PCR assays showed nearly identical numbers of HSV-1 genomes in latently infected WT and IL-6 KO mice. These studies indicate that while IL-6 plays a role in the protection of mice from lethal HSV infection, it does not substantively influence HSV replication, spread to the nervous system, establishment of latency, or reactivation.

Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) are important human pathogens that cause orofacial and genital lesions (37). During the initial infection, HSV replicates at the site of entry and then undertakes centripetal transit in sensory nerves to the ganglia, where it remains in a latent state until reactivated by stimuli such as heat and UV light (18–20, 30, 37), when it travels back down nerve axons to replicate near the initial portal of entry. The risk and consequences of HSV reactivation in vivo depend on many viral and host factors such as the virus type, the anatomical site of infection (28), the immune status of the host (25–27), and the quantity of latent viral DNA (21, 23, 29, 31). Interleukin-6 (IL-6) may be one of the host factors that influences the course of HSV infection.

IL-6 is a multifunctional cytokine produced by various cells in response to infection. It induces B-cell differentiation, production of acute-phase proteins, and fever and affects T-cell function and cortisol-mediated stress responses among other activities (1, 7, 13). Binding of IL-6 to its receptor causes homodimerization of gp130, a signal transducer common among members of the IL-6 family (for a review, see reference 13). Following receptor binding and dimerization of gp130, three distinct pathways mediate the functions of IL-6. One pathway involves JAK/STAT intracellular signaling, another involves Ras/Raf kinase signal transduction, and the third utilizes the Src kinase family (9, 11, 13, 34). A cascade of signaling initiated by these pathways triggers DNA transcription.

Previously, Kriesel et al. (16) showed that after mice were injected with antibodies to IL-6, heat- or UV light-induced reactivation of HSV-1 was decreased. The rationale underlying these experiments was that sunlight and fever, among other stresses, are known to be associated with reactivation of HSV in humans (reviewed in reference 37). In that IL-6 mediates aspects of the inflammatory response to these diverse stresses, it was reasonable to postulate a role for it in HSV reactivation. In other reports, administration of recombinant ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), a member of the IL-6 family of cytokines, is associated with a heightened rate of labial herpes recurrences in humans (15). These initial findings led us to explore the ability of murine IL-6 (mIL-6) to affect HSV-1 replication in cell culture and the course of infection, latency, and reactivation in mice. We studied the effects of exogenous IL-6 or anti-IL-6 antibodies on HSV-1 plaque-forming efficiency in cell culture, measured the virus titer in various neural tissues to which it spreads after infection, quantified the genome copies that persisted in ganglia after infection (the latent viral load), and determined the capacity of the virus to reactivate upon exposure of infected wild-type (WT) and IL-6 knockout (KO) mice to UV light.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

The neurovirulent HSV-1 (McKrae) was grown in Vero (African green monkey kidney) cells in Eagle’s minimal essential medium 199 (EMEM:199) (Quality Biologicals, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Quality Biologicals, Inc.) and 1% glutamine-streptomycin-penicillin (Life Technologies Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). BALB/3T3 and HEL (human embryonic lung) cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (Quality Biologicals, Inc.) with 10% FBS and 1% glutamine-streptomycin-penicillin.

Animals and inoculations.

Female B6129SF2 (WT) and B6,129S-IL6 homozygous knockout (KO) mice (14), 4 to 6 weeks old, were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine), housed in American Association for Laboratory Animal Care-accredited facilities, and studied under an approved animal research protocol. The mice were anesthetized with a 0.5-ml intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of ketamine and xylazine in phosphate-buffered saline. Both corneas were scarified with a 25-gauge needle, and 5 μl of virus inoculum was applied per eye. The animals received various doses from 103 to 106 PFU each. Control mice received 5 μl of phosphate-buffered saline per scarified eye.

Male BALB/c mice, 4 to 6 weeks old, were obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, Md.) and housed as above. The mice were infected via corneal scarification with 107 PFU of HSV-1 (McKrae). To ensure that the BALB/c mice survived the acute phase, at the time of infection they were passively immunized with a single intraperitoneal dose of 0.5 ml of human immunoglobulin G (IgG; Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, Ill.) diluted 1:8 in phosphate-buffered saline.

Cytokines and antibodies.

Recombinant human and murine IL-6 were obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Biological Resources Branch). Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to human IL-6 (hIL-6) and mIL-6 were purchased from R & D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, Minn.), and from Biosource International (Camarillo, Calif.). Neutralizing monoclonal antibody to human gp130 was purchased from R & D Systems, Inc. For the in vitro assays, human cytokine and antibody were used in studies with HEL cells. Murine reagents were used in studies with Vero and BALB/3T3 cells.

Plaque assays.

Duplicate monolayers of Vero, HEL, or BALB/3T3 cells in six-well dishes were pretreated for 3 h at 37°C with concentrations of either IL-6, anti-IL-6, or anti-gp130 ranging from 0 to 10 μg/ml and then infected with approximately 100 PFU of HSV-1 (McKrae) per well. The virus was diluted in medium containing the appropriate treatment and adsorbed to cells for 90 min at 37°C on a rocking platform. Infected cells were then overlaid in medium containing 0.5% pooled human IgG plus the desired concentrations of IL-6, anti-IL-6, or anti-gp130. Dishes were placed in a humidified 37°C CO2 incubator until plaques were evident. The dishes were then stained, and the plaques were counted.

Explant cocultivation.

Whole trigeminal ganglia (TG) were harvested from groups of latently infected mice (at least 30 days postinfection [p.i.]), and each pair of TG was placed onto separate Vero cell monolayers. Explants from BALB/c mice were kept in medium containing various concentrations of mIL-6 or anti-mIL-6 antibody, plus 0.1% N,N′-hexamethylene-bisacetamide (HMBA; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), 1.2% amphotericin B (Quality Biologicals), and 2% FBS. Explants from WT and IL-6 KO mice were kept in medium containing 0.1% HMBA, 1.2% amphotericin B, and 2% FBS. All explant cultures were kept in a 37°C humidified CO2 incubator. The explants were checked daily for cytopathic effects (CPE) and were carefully transferred onto fresh monolayers weekly, if necessary.

Survival and ocular virus shedding.

Groups of 10 or 20 WT and IL-6 KO mice were infected by bilateral corneal scarification and were observed daily for mortality up to day 15 post-infection (p.i.). The 50% lethal dose was calculated by the method of Lennette (22). Concurrent with monitoring survival, the number of animals shedding virus from the inoculation site was determined. On the indicated days, both eyes were swabbed with a moistened Dacron polyester-tipped applicator (Baxter Healthcare Corp., Deerfield, Ill.). The swab was placed in 1 ml of EMEM:199–10% FBS–1% glutamine-streptomycin-penicillin–1.2% amphotericin B. The culture material was plated on Vero cells and incubated for 1 h at 37°C on a rocking platform. Afterward, the cells were overlaid with medium and placed in a humidified 37°C CO2 incubator until CPE was evident.

Virus titers in tissues.

Groups of 30 WT and KO mice each were infected via corneal scarification with 103 PFU of HSV-1 (McKrae). This dose was chosen since few KO mice survived infection with higher input inocula. On days 2, 4, 7, and 11 p.i., the eyes, brain, and TG were removed from infected animals by an aseptic technique and placed into separate tubes containing 1 ml of medium (EMEM:199, 10% FBS, 1% glutamine-streptomycin-penicillin, 1.2% amphotericin B). The organs were ground with a Tekmar tissue homogenizer (VWR Scientific, McGaw Park, Ill.), and the homogenates were diluted serially and then plated in duplicate on Vero cell monolayers. The monolayers were incubated for 1 h at 37°C on a rocking platform. Afterward, the cells were overlaid with medium containing 0.5% pooled human IgG and placed in a humidified 37°C CO2 incubator until plaques were evident. The dishes were then stained, and plaques were counted.

In vivo reactivation.

Groups of WT and KO mice each were infected via corneal scarification with 103 or 104 PFU of HSV-1 (McKrae). The method used for inducing HSV-1 reactivation in vivo was recently reported (19, 20) and is a modification of an earlier procedure (18). Briefly, latently infected WT or KO mice were anesthetized and placed onto cardboard resting on top of a TM-20 transilluminator (UVP Inc., Upland, Calif.) so that one side of the head was exposed for 1 min. The mice were then turned to expose the contralateral eye for another minute. Some infected animals were not exposed, to serve as “unstressed” controls. At 48 h after UV exposure, the pair of TG was harvested, ground in 1 ml of medium, and plated on Vero cells. Monolayers were incubated at 37°C and checked daily for CPE.

Quantitative Fluorescence PCR.

WT and KO mice were infected via corneal scarification with 103 PFU of HSV-1 (McKrae). The method used for ascertaining the latent viral genome copy number in TG was recently reported in detail (19). Briefly, pairs of TG from latently infected WT and KO mice were dissected and DNA was isolated with the Puregene DNA Isolation kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.). The number of copies of latent HSV-1 DNA was quantified by real-time fluorescence PCR with the Taqman system, ABI Prism 7700 sequence detector (PE Applied Biosystems, Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.), and primers and probe specific for glycoprotein G of HSV-1 (gG-1) (19). Each reaction of 100 ng of TG DNA was done in triplicate and then repeated, for a total of six runs per animal. A positive control plasmid, pSG25 (5), was obtained from M. Challberg and used to develop a standard curve from 3 × 100 to 3 × 105 copies in the presence of 100 ng of uninfected WT TG DNA (19).

Statistical analysis.

Analyses were done with JMP software from the SAS Institute (Cary, N.C.). Comparisons between the Kaplan-Meier survival estimates were done by the log rank test. Nonparametric methods were used to analyze other data. One-way analysis of variance was used to analyze the results of plaque assays. Geometric means and one-way analysis of variance with log-transformed numbers were used to analyze the results of acute-phase tissue virus titer determinations and quantitative PCR. Means, medians, and distributions were compared by the Wilcoxon two-sample test. The proportions of animals shedding virus and samples reactivating by explant and by UV stress were compared by the two-tailed Fisher exact test.

RESULTS

Effect of IL-6 and anti-IL-6 on HSV-1 replication in vitro.

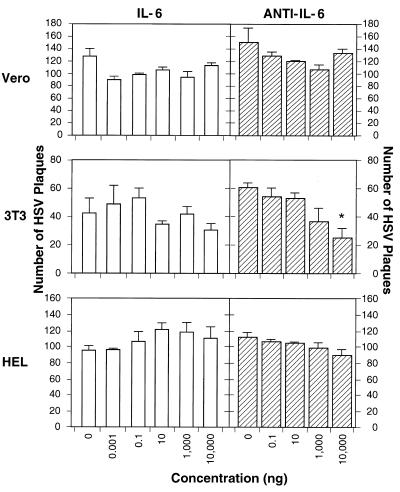

IL-6 is produced by numerous cells, including fibroblasts, upon viral infection (reviewed in references 1 and 6). Previous data indicated that anti-IL-6 inhibits HSV-1 reactivation in vivo (16). That observation might be explained if IL-6 enhanced HSV replication. Therefore, we used three different cell lines to test whether recombinant IL-6 would increase the plaquing efficiency of HSV-1 or, conversely, whether anti-IL-6 would decrease its plaquing efficiency (Fig. 1). The IL-6 dose range was chosen to span the circulating IL-6 levels found in humans (<10 pg/ml [2] to ca. 2 ng/ml [35]). We found that IL-6 did not alter HSV-1 plaquing efficiency in human, monkey, or mouse cell lines compared with no cytokine treatment (Fig. 1; P > 0.05 for all determinations).

FIG. 1.

Effect of IL-6 and anti-IL-6 on HSV-1 replication. Monolayers of Vero, HEL, or BALB/3T3 cells in six-well dishes were pretreated for 3 h at 37°C with the indicated doses of either IL-6 or anti-IL-6 and then infected with approximately 100 PFU of HSV-1 (McKrae). Virus was allowed to infect for 90 min, and cells were overlaid and kept in a 37°C incubator until plaques were evident. The mean result of duplicate experiments is shown. Error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean. Human reagents were used on HEL cells, and murine reagents were used on other cells. The asterisk indicates that the reduction in plaque number is significant (P = 0.02).

In agreement with prior reports (16), we found that anti-IL-6 had no effect on plaquing efficiency on Vero cells. The 50% IL-6 neutralization doses of the antibodies were 1 to 3 ng/ml (murine antibody) for 0.25 ng of mIL-6 per ml and 50 to 150 ng/ml (human antibody) for 2.5 ng of hIL-6 per ml (package inserts). Except for the reduction in plaque yield in BALB/3T3 cells treated with 10 μg of anti-mIL-6 per ml (P = 0.02), we found that anti-IL-6 neutralizing antibodies did not alter HSV-1 plaquing efficiency in human, monkey, or mouse cell lines compared with no antibody treatment (Fig. 1; P > 0.05 for all other determinations).

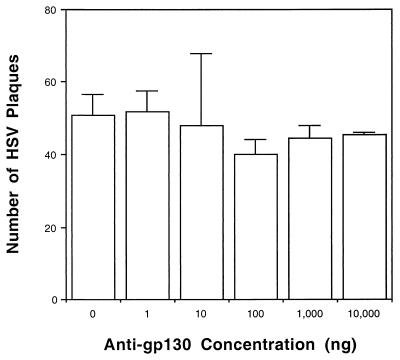

HSV-1 replication in the presence of anti-gp130.

While IL-6 appeared to have no direct effect on HSV replication in vitro, we considered it possible that other members of the IL-6 family would do so. Therefore, we determined whether inhibition of ligand binding to a common receptor for the IL-6 family of cytokines, gp130 (reviewed in reference 13), would alter HSV-1 plaquing efficiency. The 50% neutralization dose was 20 to 40 ng/ml for 0.8 ng of oncostatin-M (OSM) per ml (package inserts). Murine gp130 and anti-murine gp130 are not commercially available, and so they could not be tested in animals or in cultured murine cells. However, as shown in Fig. 2, anti-human gp130 neutralizing antibody is available, and it proved to have no effect on HSV-1 replication in human cells at all concentrations tested (P > 0.05 for all determinations). Thus, intracellular signaling through this pathway used by IL-6 family members (CNTF, leukemia inhibitory factor, OSM, and IL-11) may not play a primary role in modulating HSV replication.

FIG. 2.

HSV-1 replication in HEL cells in the presence of anti-human gp130. Monolayers of HEL cells in six-well dishes were pretreated for 3 h at 37°C with the indicated doses of anti-human gp130 and then infected with approximately 100 PFU of HSV-1 (McKrae). Virus was allowed to infect for 90 min, and cells were overlaid and kept in a 37°C incubator until plaques were evident. The mean result of duplicate experiments is shown. Error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean.

Ex vivo reactivation in the presence of IL-6.

The observation that anti-IL-6 decreased HSV-1 reactivation in vivo (16) could be explained by a direct effect of IL-6 on promoting virus reactivation from neurons. As a first step in testing this possibility, groups of 6 to 10 BALB/c mice latently infected with HSV-1 were sacrificed on day 54 p.i. and their TG were harvested. The explanted TG were treated with concentrations of mIL-6 ranging from 0 to 10 μg/ml, with or without the demethylating agent HMBA. This range was chosen to span the IL-6 levels found in murine TG, which are approximately 1 ng/ml (8) and 12 to 21 ng/ml (4). Monolayers were observed daily for CPE. Consistent with prior reports (3), the presence of HMBA increased the rate of virus reactivation (Table 1). However, IL-6 did not alter the rate of HSV-1 ex vivo reactivation at the concentrations tested, nor did it alter the rates observed in cultures treated with HMBA (P > 0.05 for all determinations).

TABLE 1.

Explant cocultivation of latently infected TG in the presence of exogenous IL-6

| IL-6 concn (μg/ml) | Time (days) to reactivationad

|

Proportion reactivatingbd

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMBA present | HMBA absent | HMBA | No HMBA | |

| 0.0 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 10.8 ± 0.4 | 9/10 | 8/9 |

| 0.1 | 8.1 ± 0.6 | 8.7 ± 1.2 | 9/10 | 7/10 |

| 1.0 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 10.1 ± 0.9 | 6/6 | 9/10 |

| 10.0 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | NDc | 6/6 | ND |

Mean ± standard error of the mean.

Number reactivating/total number tested.

ND, not done.

All P values within a column were >0.05 compared to untreated controls.

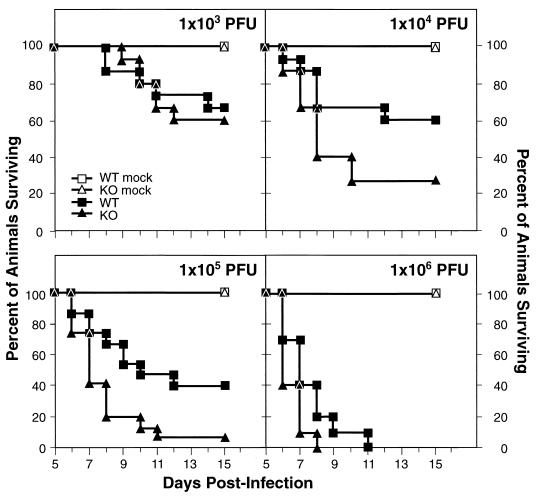

Survival of animals during acute HSV-1 infection.

Having found no evidence of IL-6 effects on HSV-1 replication in vitro or reactivation ex vivo, we sought to delineate its effects, if any, in vivo. To define the effects of IL-6 on virus-induced mortality, groups of 5 (mock-infected) or 10 to 15 (infected) mice each were infected by bilateral corneal scarification followed by inoculation with 103 to 106 PFU of HSV-1 (McKrae). Mortality was scored daily for the first 15 days p.i. All of the mock-infected animals survived. As shown in Fig. 3, at 103 PFU 67% of the WT mice (10 of 15) survived, compared with 60% of the KO mice (9 of 15) (P = 0.76). At an infectious dose of 104 PFU, 60% of WT mice (9 of 15) and 27% KO mice (4 of 15) survived (P = 0.06). The effects of IL-6 in protecting mice were most evident with higher doses of HSV-1, since infection at 105 PFU resulted in the survival of 40% of WT mice (6 of 15) but only 7% of KO mice (1 of 15) (P = 0.01). At a titer of 106 PFU, no animals in either group survived beyond day 8 p.i. (KO) or day 11 p.i. (WT) (P = 0.07). The cumulative data revealed a sixfold-higher 50% lethal dose of HSV-1 in WT mice than in IL-6 KO mice (1.7 × 104 PFU and 2.7 × 103 PFU, respectively).

FIG. 3.

Survival after HSV-1 inoculation. Groups of WT and IL-6 KO mice were infected by corneal scarification with doses from 103 PFU to 106 PFU of HSV-1 (McKrae). Control WT and KO animals were mock infected. Survival was monitored for the first 15 days p.i. The sample sizes were 5 animals for each control group, 15 animals for each experimental group infected with 103 PFU to 105 PFU, and 10 animals for mice infected with 106 PFU.

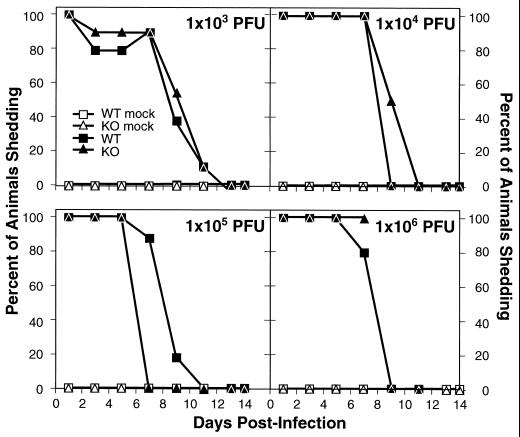

Ocular shedding during acute infection.

To monitor HSV-1 shedding at the site of inoculation, eye swabs were taken on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 14 p.i. (Fig. 4). As expected, none of the mock-infected mice shed virus, while at the highest dose the animals did not survive beyond day 8 p.i. (KO) or day 11 p.i. (WT) (Fig. 3). Thus, the final swabs at the highest dose were taken on day 7 p.i. (KO) and day 11 p.i. (WT). Shedding was evident when first assayed 24 h p.i. and decreased over time. Only on day 7, in mice infected with 105 PFU, was there a strong trend for a difference in the percentage of animals shedding virus (85% WT and 0% KO [P = 0.07]); however, this difference did not persist. Otherwise, there were no significant differences in the proportions of animals shedding virus over time at any dose tested, regardless of the IL-6 background of the mice. The P values for comparison where differences occurred between the WT and KO mice were as follows: 103 PFU, day 3, P = 1.0; day 5, P = 1.0; day 9, P = 0.66; 104 PFU, day 9, P = 0.07; 105 PFU, day 7, P = 0.07; day 9, P = 1.0; 106 PFU, day 7, P = 1.0.

FIG. 4.

Ocular virus shedding after HSV-1 infection. (WT) and IL-6 KO mice were infected with HSV-1 (McKrae) as described in the legend to Fig. 3. On the indicated days, corneal swabs were taken for virus isolation from the animals in the experiment in Fig. 3. Each point represents the virus recovery percentage for 5 mice (mock infected) or 10 mice (WT and KO groups). At 106 PFU, the final swab for the KO mice was on day 7 p.i. because all animals in this group were dead by day 8 p.i. (Fig. 3). Likewise, all WT mice given this dose were dead by day 11 p.i.

HSV-1 titers during acute infection.

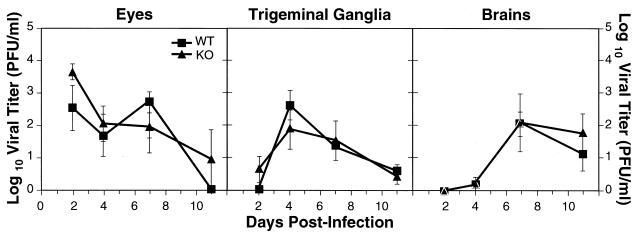

After the initial eye infection, the virus spread to the TG and then to the brain. To study HSV-1 pathogenesis in this mouse model, we measured the amount of virus found in the eyes, TG, and brain on days 2, 4, 7, and 11 p.i. These tissues were harvested from groups of five mice each and at all time points. Lack of IL-6 in the KO mice did not seem to affect HSV-1 in vivo replication, since there were similar HSV titers in the eyes, TG, and brains of WT and IL-6 KO mice (Fig. 5). The P values comparing the groups were as follows: eyes, day 2, P = 0.17; day 4, P = 0.68; day 7, P = 0.43; day 11, P = 0.35; TG, day 2, P = 0.14; day 4, P = 0.37; day 7, P = 0.80; day 11, P = 0.72; brains, day 2, not applicable; day 4, P = 0.84; day 7, P = 0.97; day 11, P = 0.45. A progression of infection was evident from this experiment, since virus titers initially appeared in the eyes (day 2 p.i.), peaked in the TG on day 4 p.i. for both groups, and then peaked in the brain on day 7 p.i.

FIG. 5.

HSV-1 titers in the eyes, TG, and brains of WT and IL-6 KO mice during acute infection. Mice were infected with 103 PFU of HSV-1 (McKrae). On the indicated days, the eyes, pooled TG, and brains were harvested, and viral titers were determined on Vero cells. Each point represents the log value of the geometric mean virus titer ± standard error for five animals. Log values shown as zero actually reflect undetectable levels of virus.

Explant cocultivation of latently infected ganglia.

HSV-1 establishes a latent infection in the TG and can be reactivated in vitro by explant cocultivation. To detect any potential differences in the establishment of latency and the rate of in vitro reactivation, IL-6 KO and WT mice (survivors from the experiments in Fig. 3) were sacrificed on day 34 p.i. and their TG were harvested. The explanted ganglia were cultured for 13 days, and the results are summarized in Table 2. For the animals infected at 103 PFU, virus reactivated from explanted ganglia in 80% of the WT mice (8 of 10) and 78% of the KO mice (7 of 9) (P = 0.91). There were no significant differences in the average time to reactivation between these groups (10.4 days for WT mice and 10.3 days for KO mice; P = 0.80). In an experiment with 104 PFU, 100% of TG yielded reactivated HSV-1 from both groups and there was no difference in the time to reactivation (10.1 days for WT mice and 11.0 days for KO mice; P = 0.75).

TABLE 2.

Explant cocultivation of latently infected TG

| Mouse group | No. of TG pairs reactivating/total no. tested | Time (days) to reactivationa |

|---|---|---|

| Mock-infected WT | 0/5 | NAb |

| Mock-infected KO | 0/5 | NA |

| WT, 103 PFU | 8/10 | 10.4 ± 1.2 |

| KO, 103 PFU | 7/9 | 10.3 ± 1.3 |

| WT, 104 PFU | 9/9 | 10.1 ± 1.0 |

| KO, 104 PFU | 4/4 | 11.0 ± 1.5 |

Mean ± standard error of the mean.

NA, not applicable.

HSV-1 in vivo reactivation following UV exposure.

Because spontaneous reactivation of HSV in mice is rare, in vivo reactivation must be induced. Using UV radiation as a stress (18, 19) we investigated whether there would be differences in rates of in vivo reactivation between the two study groups. The experiment was performed twice, and the results shown are the combined data from the two independent experiments. After latency was established (day 40 p.i. in experiment 1, and day 46 p.i. in experiment 2), the animals were exposed to UV-B radiation for 1 min per eye. TG were harvested 48 h later, homogenized, and plated onto Vero cells. No virus was recovered from UV-treated, mock-infected mice. Although HSV-1 reactivated in slightly fewer KO mice, this difference was not significant. Specifically, HSV reactivated in 70% of WT mice (14 of 20) compared with 50% of IL-6 KO mice (10 of 20) (P = 0.33) (Table 3) receiving 103 PFU. Additionally, there was no substantive difference in the average time to reactivation between the groups (1.9 days for WT mice and 2.1 days for KO mice; P = 0.85). Similarly, there was no statistical difference in the rates of reactivation in WT and KO mice receiving 104 PFU of virus. To ensure that the reactivation seen was due solely to the UV stress, we homogenized TG from latently infected but unstressed animals: none of the WT and two of nine KO animals yielded spontaneously reactivated virus.

TABLE 3.

In vivo reactivation of latently infected animals

| Mouse group | No. of TG pairs reactivating/total no. tested | Time (days) to reactivationa |

|---|---|---|

| WT, 103 PFU, UV | 14/20 | 1.9 ± 0.3 |

| KO, 103 PFU, UV | 10/20 | 2.1 ± 0.3 |

| WT, 104 PFU, UV | 10/10 | 3.0 ± 0.1 |

| KO, 104 PFU, UV | 9/10 | 3.2 ± 0.1 |

| WT, 103 PFU, no UV | 0/9 | NAb |

| KO, 103 PFU, no UV | 2/9 | 2.0 ± 0.0 |

| WT, 104 PFU, no UV | 1/5 | 3.0 ± 0.0 |

| KO, 104 PFU, no UV | 1/3 | 3.0 ± 0.0 |

Mean ± standard error of the mean.

NA, not applicable.

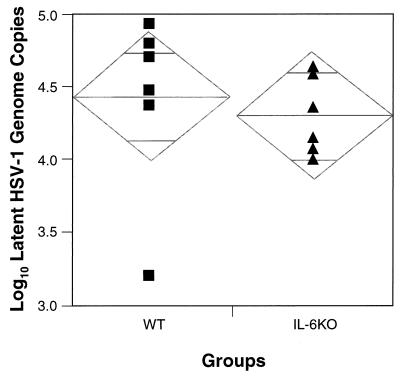

Quantitative PCR to determine the latent viral load in TG.

As a means of determining the amount of latent HSV-1 present in the TG, we used a real-time quantitative PCR assay based on displacement of a fluorescently labeled probe to gG-1 sequences (19). Groups of six HSV-1 latently infected WT and KO animals each were sacrificed on day 82 p.i., and individual TG were harvested for DNA extraction and subsequent PCR. By comparing the PCR results to a standard curve, run simultaneously, of triplicate serial dilutions of a gG-1-containing plasmid, we estimated the genome copy number in test samples. We found nearly identical amounts of latent HSV-1 DNA copies in the TG of the WT and KO mice (P = 0.69) (Fig. 6). Specifically, there was an average of 4.4 ± 0.1 log units of latent virus per 100 ng of mouse TG DNA in the WT group (95% confidence interval, 4.2 to 4.6 log units) versus 4.3 ± 0.1 log units in the IL-6 KO group (95% confidence interval, 4.2 to 4.4 log units).

FIG. 6.

Quantitation of latent HSV-1 DNA copy numbers by PCR. Groups of six latently infected WT and IL-6 KO mice were sacrificed on day 82 p.i., and individual TG were harvested for DNA extraction. Each point represents the log value of the geometric mean copy number for six replicate PCR determinations per pooled TG from each animal. The horizontal line along the width of a diamond indicates the combined mean of HSV-1 DNA copy numbers for all six mice per group. The shorter horizontal lines above and below this indicate the 95% confidence intervals around the mean.

DISCUSSION

IL-6 is an obvious candidate as a proinflammatory mediator of the so-called “fever blister” or “cold sore.” This cytokine can be found in nasal secretions and in the blood during influenza and other common respiratory infections (10). The magnitude of the local and circulating IL-6 response correlates with the height of the febrile response and the severity of other illness symptoms (10). Administration of IL-6 to human volunteers and to cancer patients elicits an acute febrile illness whose severity increases with the dose (24, 36).

There is circumstantial evidence linking IL-6 and HSV reactivation. IL-6 is pyrogenic, as described above, and fever is a known stimulus of HSV reactivation in humans (reviewed in reference 37). Hyperthermia also induces HSV reactivation in mice (30). The IL-6 level increases in latently infected murine TG (32), but one study (4) found no correlation between HSV reactivation by hyperthermia and cytokine level. However, the in vitro reactivation procedure used (heating of dissociated TG cell cultures for 3 h) was not physiologically relevant. In vivo hyperthermia models can result in reactivation from the TG of as many as 67% (30) to 90% of mice (18a) and may reveal a link to IL-6 levels.

Along with fever, sunlight can trigger HSV reactivations in humans (reviewed in reference 37), and UV exposure of mice induces reactivation from the TG (18–20; also see above). Exposure to UV light increases IL-6 levels in humans (35) and in uninfected murine TG (33).

In addition to these broad biological effects of IL-6, there are data further implicating it in the reactivation of HSV. First, Kriesel et al. showed that anti-IL-6 blocks heat- or UV-induced reactivation of HSV-1 in mice (16). Second, experimental administration of recombinant CNTF for treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is associated with a heightened rate of labial herpes recurrences (15). CNTF and its receptor form a complex with gp130 (12), the signal transducer also used by IL-6. Third, IL-6 response elements have been found in the promoter region of the latency-associated transcript (17). To better understand the relationship between IL-6 and HSV reactivation, we conducted a series of in vitro and in vivo experiments.

Overall, IL-6, anti-IL-6, or anti-gp130 had no effect on HSV-1 in vitro replication as determined by a plaque assay (Fig. 1 and 2), showing that IL-6 or gp130 signaling may not play a primary role in HSV replication in vitro. Exogenous IL-6 had no effect on HSV-1 ex vivo reactivation as determined by explant cocultivation (Table 1). Although IL-6 had no detectable effect on replication in vitro or in vivo or reactivation ex vivo (Fig. 1, 4, and 5; Table 1), it was important in protecting mice from lethal HSV infection. IL-6, IL-1, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) are inflammatory cytokines important for the acute-phase response to infection. The IL-6 KO mice have a deficient acute-phase inflammatory response to vaccinia virus, vesicular stomatitis virus, and Listeria monocytogenes (14). Thus, the response to HSV may be hampered as well. This might help to explain the differences in survival between the KO and WT mice, although the titers in the brains were similar. Finally, lack of IL-6 in KO mice did not prevent the establishment, maintenance, of or reactivation from HSV-1 latency, as evidenced by the explant cocultivation, UV irradiation, and quantitative PCR studies (Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 6).

Other than its effects on survival (Fig. 3), the present studies show that IL-6 had no significant effect on the various phases of HSV-1 infection in mice. The IL-6 KO mice were less able to control the acute infection with high doses of virus. However, this did not result in an increased latent viral load or in increased rates of reactivation compared to WT. When Kriesel et al. (16) administered anti-IL-6 antibodies prior to UV exposure of latently infected BALB/c mice, they observed a marked reduction in reactivation (20%) compared to that in control animals (75%). In our studies with IL-6 KO mice, we saw no difference in UV-induced reactivation from that in WT mice. These observations indicate that the association of IL-6 with HSV infection and its reactivation, if any, is an indirect or complex one. Since other members of the IL-6 family (IL-11, CNTF, Leukemia inhibitory factor, and OSM) are known to have overlapping functions (reviewed in references 1 and 13), it is possible that in IL-6 knockout mice, other IL-6 family members or perhaps non-IL-6 cytokines may be compensating for the activity of the missing IL-6 in promoting HSV-1 spread, latency, and reactivation.

Levels of TNF-α, for example, increase during the acute and latent phases of HSV infection in mice (32), as do levels of IL-6 (8, 32). Like IL-6, TNF-α levels increase after exposure of mouse corneas to UV (33). It is possible that this cytokine substitutes for IL-6 in the KO mice. Experiments are in progress to explore direct responses to exogenously administered IL-6 and other cytokines in latently infected WT and gene KO mice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

An Intramural Research Training Award from the NIH supported R. LeBlanc as a postdoctoral fellow.

We thank Jeffrey Cohen and Brian Kelsall for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akira S, Taga T, Kishimoto T. Interleukin-6 in biology and medicine. Adv Immunol. 1993;54:1–78. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer J, Herrmann F. Interleukin-6 in clinical medicine. Ann Hematol. 1991;62:203–210. doi: 10.1007/BF01729833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein D I, Kappes J C. Enhanced in vitro reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus from neural and peripheral tissues with hexamethylenebisacetamide. Arch Virol. 1988;99:57–65. doi: 10.1007/BF01311023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carr D J, Noisakran S, Halford W P, Lukacs N, Asensio V, Campbell I L. Cytokine and chemokine production in HSV-1 latently infected trigeminal ganglion cell cultures: effects of hyperthermic stress. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;85:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Challberg M. A method for identifying the viral genes required for herpesvirus DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9094–9098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.9094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durum S K, Muegge K. Cytokines linking the immune and inflammatory systems: IL-1, TNF, IL-6, IFN-αβ, and TGF-β. In: Rich R R, editor. Clinical immunology: principles and practice. Vol. 1. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby Publishers; 1996. pp. 350–362. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gijbels K, Billiau A. Interleukin-6: general biological properties and possible role in the neural and endocrine systems. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1992;2:83–97. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halford W P, Gebhardt B M, Carr D J. Persistent cytokine expression in trigeminal ganglion latently infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Immunol. 1996;157:3542–3549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hallek M, Neumann C, Schaffer M, Danhauser-Riedl S, von Bubnoff N, de Vos G, Druker B J, Yasukawa K, Griffin J D, Emmerich B. Signal transduction of interleukin-6 involves tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple cytosolic proteins and activation of Src-family kinases Fyn, Hck, and Lyn in multiple myeloma cell lines. Exp Hematol. 1997;25:1367–1377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayden F G, Fritz R S, Lobo M C, Alvord W G, Strober W, Straus S E. Local and systemic cytokine responses during experimental human influenza A virus infection. Relation to symptom formation and host defense. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:643–649. doi: 10.1172/JCI1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirano T, Matsuda T, Nakajima K. Signal transduction through gp130 that is shared among the receptors for the interleukin 6 related cytokine subfamily. Stem Cells. 1994;12:262–277. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530120303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ip N Y, Nye S H, Boulton T G, Davis S, Taga T, Li Y, Birren S J, Yasukawa K, Kishimoto T, Anderson D J, et al. CNTF and LIF act on neuronal cells via shared signaling pathways that involve the IL-6 signal transducing receptor component gp130. Cell. 1992;69:1121–1132. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90634-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kishimoto T, Akira S, Narazaki M, Taga T. Interleukin-6 family of cytokines and gp130. Blood. 1995;86:1243–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kopf M, Baumann H, Freer G, Freudenberg M, Lamers M, Kishimoto T, Zinkernagel R, Bluethmann H, Kohler G. Impaired immune and acute-phase responses in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;368:339–342. doi: 10.1038/368339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kriesel J D, Araneo B A, Petajan J P, Spruance S L, Stromatt S. Herpes labialis associated with recombinant human ciliary neurotrophic factor. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1046. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.1046. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kriesel J D, Gebhardt B M, Hill J M, Maulden S A, Hwang I P, Clinch T E, Cao X, Spruance S L, Araneo B A. Anti-interleukin-6 antibodies inhibit herpes simplex virus reactivation. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:821–827. doi: 10.1086/513977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kriesel J D, Ricigliano J, Spruance S L, Garza H H, Hill J M. Neuronal reactivation of herpes simplex virus may involve interleukin-6. J Neurovirol. 1997;3:441–448. doi: 10.3109/13550289709031190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laycock K A, Lee S, Brady R H, Pepose J S. Characterization of a murine model of recurrent herpes simplex viral keratitis induced by ultraviolet B radiation. Investig Ophthalmol Visual Sci. 1991;32:2741–2746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.LeBlanc, R. Unpublished data.

- 19.LeBlanc R A, Pesnicak L, Godleski M, Straus S E. The comparative effects of famciclovir and valacyclovir on HSV-1 infection, latency and reactivation in mice. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:594–599. doi: 10.1086/314962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LeBlanc, R. A., L. Pesnicak, M. Godleski, and S. E. Straus. Treatment of HSV-1 infection with immunoglobulin or acyclovir: comparison of their effects on viral spread, latency and reactivation. Virology, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Lekstrom-Himes J A, Pesnicak L, Straus S E. The quantity of latent viral DNA correlates with the relative rates at which herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 cause recurrent genital herpes outbreaks. J Virol. 1998;72:2760–2764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2760-2764.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lennette E H. General principles underlying laboratory diagnosis of virus and rickettsial infections. In: Lennette E H, Schmidt N J, editors. Diagnostic procedures of virus and rickettsial disease. New York, N.Y: American Public Health Association; 1964. p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maggioncalda J, Mehta A, Su Y H, Fraser N W, Block T M. Correlation between herpes simplex virus type 1 rate of reactivation from latent infection and the number of infected neurons in trigeminal ganglia. Virology. 1996;225:72–81. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mastorakos G, Chrousos G P, Weber J S. Recombinant interleukin 6 activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:1690–1694. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.6.8263159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nash A A, Field H, Quartey-Papafio R. Cell-mediated immunity in herpes simplex virus-infected mice: induction, characterization and antiviral effects of delayed-type hypersensitivity. J Gen Virol. 1980;48:351–357. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-48-2-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nash A A, Cambouropoulos P. The immune response to herpes simplex virus. Semin Virol. 1993;4:181–186. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oakes J. Role for cell-mediated immunity in the resistance of mice to subcutaneous herpes simplex virus infection. Infect Immun. 1975;12:166–172. doi: 10.1128/iai.12.1.166-172.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reeves W C, Corey L, Adams H G, Vontver L A, Holmes K K. Risk of recurrence after first episodes of genital herpes: relation to HSV type and antibody response. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:315–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198108063050604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawtell N. The probability of in vivo reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 increases with the number of latently infected neurons in the ganglia. J Virol. 1998;72:6888–6892. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6888-6892.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawtell N M, Thompson R L. Rapid in vivo reactivation of herpes simplex virus in latently infected murine ganglionic neurons after transient hyperthermia. J Virol. 1992;66:2150–2156. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2150-2156.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawtell N M, Poon D, Tansky C S, Thompson R L. The latent herpes simplex virus type 1 genome copy number in individual neurons in virus strain specific and correlates with reactivation. J Virol. 1998;72:5343–5350. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5343-5350.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimeld C, Whiteland J L, Williams N A, Easty D L, Hill T J. Cytokine production in the nervous system of mice during acute and latent infection with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:3317–3325. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-12-3317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimeld C, Easty D L, Hill T J. Reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 in the mouse trigeminal ganglion: an in vivo study of virus antigen and cytokines. J Virol. 1999;73:1767–1773. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1767-1773.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taga T. Gp130, a shared signal transducing receptor component for hematopoietic and neuropoietic cytokines. J Neurochem. 1996;67:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67010001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urbanski A, Schwarz T, Neuner P, Krutmann J, Kirnbauer R, Kock A, Luger T A. Ultraviolet light induces increased circulating interleukin-6 in humans. J Investig Dermatol. 1990;94:808–811. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12874666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weber J S, Yang J C, Topalian S T, Parkinson D R, Schwartzentruber D S, Ettinghausen S E, Gunn H, Mixon A, Kim H, Cole D, et al. Phase 1 trial of subcutaneous interleukin 6 in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:499–505. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitley R J. Herpes simplex viruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 2297–2342. [Google Scholar]