Abstract

Background

The role of duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) as an early detection and intervention target to improve outcomes for individuals with first-episode psychosis is unknown.

Study Design

PRISMA/MOOSE-compliant systematic review to identify studies until February 1, 2023, with an intervention and a control group, reporting DUP in both groups. Random effects meta-analysis to evaluate (1) differences in DUP in early detection/intervention services vs the control group, (2) the efficacy of early detection strategies regarding eight real-world outcomes at baseline (service entry), and (3) the efficacy of early intervention strategies on ten real-world outcomes at follow-up. We conducted quality assessment, heterogeneity, publication bias, and meta-regression analyses (PROSPERO: CRD42020163640).

Study Results

From 6229 citations, 33 intervention studies were retrieved. The intervention group achieved a small DUP reduction (Hedges’ g = 0.168, 95% CI = 0.055–0.283) vs the control group. The early detection group had better functioning levels (g = 0.281, 95% CI = 0.073–0.488) at baseline. Both groups did not differ regarding total psychopathology, admission rates, quality of life, positive/negative/depressive symptoms, and employment rates (P > .05). Early interventions improved quality of life (g = 0.600, 95% CI = 0.408–0.791), employment rates (g = 0.427, 95% CI = 0.135–0.718), negative symptoms (g = 0.417, 95% CI = 0.153–0.682), relapse rates (g = 0.364, 95% CI = 0.117–0.612), admissions rates (g = 0.335, 95% CI = 0.198–0.468), total psychopathology (g = 0.298, 95% CI = 0.014–0.582), depressive symptoms (g = 0.268, 95% CI = 0.008–0.528), and functioning (g = 0.180, 95% CI = 0.065–0.295) at follow-up but not positive symptoms or remission (P > .05).

Conclusions

Comparing interventions targeting DUP and control groups, the impact of early detection strategies on DUP and other correlates is limited. However, the impact of early intervention was significant regarding relevant outcomes, underscoring the importance of supporting early intervention services worldwide.

Keywords: duration of untreated psychosis, outcome, early detection, early intervention, meta-analysis

Introduction

Schizophrenia is one of the most debilitating and functionally limiting disorders.1,2 To ameliorate poor outcomes of psychosis during its early clinical stages,3 early detection and early intervention have the potential to impact the critical period before and after the first episode of psychosis (FEP).4,5 Early detection focuses on the detection of early signs and symptoms and is based on community awareness6 and outreach efforts7 to reduce delays in access to care, which are currently prolonged until an appropriate intervention is provided.8,9 Strategies for early detection include active strategies, such as workshops for referral sources, which include healthcare (ie, community mental health or general healthcare services), educational, or community/governmental organization professionals.10 Additionally, general public awareness campaigns, including TV or radio appearances, theater advertisements, high school art contests, and sports sponsorships, are also potential outreach strategies to support early detection. Meanwhile, early intervention focuses on the provision of optimal treatments in these early phases of the psychotic disorder and is based on multidisciplinary teams of mental health professionals for individuals with early-onset psychosis, providing multimodal psychosocial and psychopharmacological interventions.

Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) is usually defined as the period between the onset of psychosis and the start of treatment,11 although other definitions have been considered.12,13 DUP has been studied as a prognostic factor in schizophrenia. DUP has been associated with poor outcomes, including poor functioning.8,14–18 There is also highly suggestive evidence for a relationship between longer DUP and more severe positive symptoms, more severe negative symptoms, and lower chances of remission.16 Furthermore, there is suggestive evidence for an association between longer DUP and more severe global psychopathology.16 It has also been suggested that the association between DUP and psychosocial function may be an artifact of early detection, creating the illusion that early intervention is associated with improved outcomes.19 Hence, early detection programs may ascertain individuals with shorter DUP, less severe symptoms, and more individuals with affective psychosis.20

Interventions to reduce DUP based on early detection and early intervention in FEP have been developed4,21 based on the hypothesis that prolonged DUP leads to significant neurological and psychosocial damage that worsens the illness course of psychotic disorders.22 Early Intervention services (EIS) have been implemented to reduce DUP with promising results. In EIS, multidisciplinary teams of mental health professionals provide multimodal treatment, including different psychosocial and psychopharmacological interventions that are tailored to the needs of each patient.4 EIS is often considered the gold standard for the treatment of patients with early-phase psychosis.4

A meta-analysis published in this journal, including 16 studies up to April 2017, evaluated the efficacy of interventions to reduce DUP, with non-significant modest results (Hedges’ g = 0.12, P > .05).14 The frequency distributions of DUP are usually skewed, with outliers with very long DUP.23 Efforts to alter DUP by establishing early detection and intervention services have the potential to both detect individuals with FEP earlier and also to detect and intervene in those individuals that would have otherwise remained untreated.24 Thus, the inclusion of these patients could offer an unrealistically pessimistic picture of the impact of early detection efforts based on the alteration of DUP, artificially increasing DUP. Thus, other outcomes and correlates targeted by early detection and early intervention strategies need to be evaluated besides the reduction of DUP to understand the real-world impact of early detection and EIS in FEP. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the impact of early detection and intervention strategies on the reduction of DUP and mental health outcomes in first-episode psychosis. This study aimed to systematically review the evidence and provide meta-analytic data for (a) differences in DUP in individuals in early detection and intervention services vs individuals from the control group, (b) the efficacy of early detection strategies regarding real-world correlates at baseline (service entry), and (c) the efficacy of early intervention strategies on real-world outcomes at follow-up.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted according to the PRISMA 2020, (Supplementary table 1)25 and the MOOSE checklists (Supplementary table 2),26 following the EQUATOR Reporting Guidelines.27

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

A systematic search was used to identify relevant articles, and three qualified psychiatrists (GSP, AA, CAy) independently implemented a two-step literature search, looking at the titles and abstracts first, and the full text of the articles in a second step. The following terms were applied: (“first episode psych*” OR “FEP” OR “early-onset psychosis” OR “DUP” OR “duration untreated psych*”) AND (“reduc*” OR “decreas*” OR “early” OR “early intervention” OR “early detection” OR “service”). Researchers conducted the electronic search in PubMed and Web of Science database, incorporating the Web of Science Collection, BIOSIS Citation Index, KCI-Korean Journal, MEDLINE, Russian Science Citation Index, SciELO Citation Index, and Ovid/Psych databases from inception until February 01, 2023, without language restrictions. Second, we manually reviewed all references from the selected articles and extracted relevant additional articles. Articles identified were screened as abstracts, and after the exclusion of those which did not meet our inclusion criteria, the full texts of the remaining articles were assessed for eligibility, and decisions were made regarding their inclusion in the review.

The following inclusion criteria were used to select the articles: (a) individual studies, including conference proceedings; (b) conducted in individuals with FEP; (c) with both an intervention and a control group (including no intervention or historic control or alternative later intervention/treatment as usual—TAU—); (d) evaluating DUP in both groups as an outcome measure or a mediator (as mean ± SD or median) (definitions in Supplementary table 3); (e) reporting the impact of early detection or intervention in ≥1 relevant outcome for both groups; and (f) published in any language. Exclusion criteria were: (a) reviews, clinical cases, and protocols; (b) studies not reporting DUP in both groups; (c) studies without an independent control group; and (d) studies not reporting any outcome of interest. For the meta-analysis, additional inclusion criteria were: (a) full reporting of the correlates or outcomes of interest (ie, mean ± SD or %, see below) in both groups and (b) non-overlapping samples as defined by the study program and recruitment period.

Outcome Measures and Data Extraction

Three qualified psychiatrists (AA, EMB, JSV), independently carried out data extraction, which was cross-checked by another author (GSP). The variables extracted included: author, year, program, country, sample size, mean age, % males, DUP, % affective psychosis, control characteristics, main correlates/outcomes (positive symptoms, negative symptoms, total psychopathology, depressive symptoms, quality of life, functioning, remission, relapse, employment, hospitalization) at baseline and longitudinally at the end of the study, quality assessment (see below), and key findings including other outcomes. DUP, positive symptoms, negative symptoms, total psychopathology, depressive symptoms, quality of life, and functioning were evaluated using continuous data (mean ± SD) in both groups. For the intervention strategies section, the results from baseline to the end of the study were evaluated. Remission, relapse, employment, and admissions rates were evaluated categorically (%) in both groups, at baseline and follow-up, respectively.

Strategy for Data Synthesis

For the systematic review, we provided a narrative synthesis of the findings, structured around core outcomes and themes, excluding findings estimated meta-analytically, which were not repeated or expanded in this section. For the meta-analyses, the outcome measure was estimated when ≥3 studies were available by calculating the Hedges’ g for all correlates/outcomes to favor comparability. Notably, the meta-analysis of DUP and the meta-analytic correlates of early detection strategies are cross-sectional, while the analyses of meta-analytic outcomes of early intervention strategies are longitudinal and consider changes from baseline to follow-up, thus allowing the evaluation of changes on different scales for the same outcomes. Since high heterogeneity was expected, random effects meta-analyses were conducted.28 The presence of publication bias was assessed by Egger’s test,29 complemented by the “trim and fill” method to correct for the presence of missing studies when a risk of publication bias (ie, small sample bias) was detected. Heterogeneity among study point estimates was assessed using Q statistics. The proportion of the total variability in the effect size estimates was evaluated with the I2 index30 and considered statistically significant when P < .05. I2 > 50% is typically considered an indication of high variability in the effect size estimates. We conducted sub-analyses and meta-regression analyses for our three main research questions whenever ≥4 studies were available, including ≥2 studies per category in the categorical correlates/outcomes, to estimate the association between the efficacy of the intervention on each of the correlates/outcomes and (1) program continent (Europe vs America vs Australasia), (2) FEP diagnosis (% affective psychosis), (3) control content (TAU vs no intervention vs historic control), (4) mean age, (5) sex (% males), (6) DUP, (7) duration of the intervention—only for the intervention outcomes—, and (8) study quality (weak vs moderate vs strong). Further harmonization was not required for any of the outcomes as they were not dependent on different scales. We carried out “leave one out” analyses for the meta-analysis on differences in DUP in individuals in early detection and intervention services vs individuals from the control group. All P values reported in the meta-analyses were two-sided, with alpha = .05. Comprehensive Meta-analysis (CMA) V331 was used to perform the analyses.

Risk of Bias (Quality) Assessment

The study quality was assessed using the “Effective Public Health Practice Project” (EPHPP),32,33 as most studies were expected not to be randomized. The following items were evaluated as good, fair, or poor: (a) selection bias, (b) design, (c) confounders, (d) blinding, (e) data collection, and (f) dropouts. The overall quality was rated in three categories: weak, moderate, or strong. Studies were evaluated as strong when none of the items was rated as poor; moderate if one item was rated as poor; and weak if ≥2 a–f items were evaluated as poor. After discussion with the corresponding author, 100% discrepancies were resolved.

Results

The literature search yielded 6229 citations, which were screened for eligibility, and 33 articles were finally included in the systematic review and meta-analysis (figure 1). The database included 9093 individuals: 5288 in the intervention group and 3805 in the control group. The total sample size (including both intervention and control groups) of the included studies ranged from 6534 to 123435 individuals (Supplementary table 4). The mean age of the sample ranged from 21.235,36 to 31.137 years. The proportion of males ranged from 45.3%38 to 81.5%.39

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flowchart outlining study selection process.

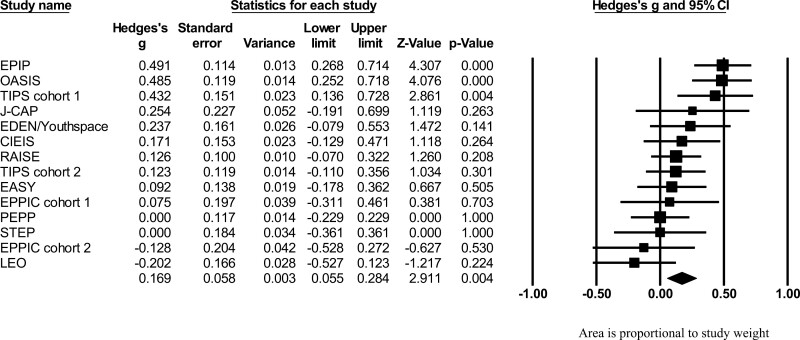

Meta-analysis of DUP

Altogether, 14 cohorts from 12 different EIS (n = 2938) provided meta-analytic data to compare DUP in an intervention (n = 1616) vs a control group (n = 1312). We found that the early detection/intervention group reduced DUP (g = 0.168, 95% CI = 0.055–0.283) compared to the control group, with a small effect size (figure 2). Heterogeneity was significant among the services (Q = 29.109 P = .006 I = 55.34%). Publication bias was not detected (Egger’s test = 1.83, P = .309). In “leave one out” analyses, the statistical significance did not change in any scenario: the maximum ES was when LEO was removed (g = 0.197, 95% CI = 0.087–0.306), and the minimum ES was when OASIS was removed (g = 0.142, 95% CI = 0.033–0.267).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of strategies to reduce DUP. Area is proportional to study weight.

Meta-analytic Results of Early Detection Strategies

Studies reported (in descending order of frequency) on negative symptoms (k = 10, n = 2255), positive symptoms (k = 8, n = 1637), functioning (k = 8, n = 2192), total psychopathology (k = 7, n = 1934), employment rates (k = 7, n = 2554), quality of life (k = 4, n = 1002), depressive symptoms (k = 3, n = 610), and admission rates (k = 3, n = 754) (table 1, figure 3).

Table 1.

Meta-analytic Outcomes of Early Detection Strategies

| Outcome | k Studies | n INT | n CTRL | Hedges’ g | Z Scores | P | Test for Heterogeneity | Egger’s Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | Q | I 2 | P | T Values | P | |||||||

| Functioninga | 8 (10) | 1182 | 1010 | 0.281 | 0.073 | 0.488 | 2.653 | .008 | 27.310 | 74.368 | <.001 | 0.209 | .841 |

| Total psychopathologyb | 7 (10) | 1032 | 902 | 0.186 | −0.173 | 0.546 | 1.016 | .310 | 49.654 | 87.916 | <.001 | 0.307 | .771 |

| Admission rates | 3 (3) | 348 | 406 | 0.179 | −0.146 | 0.504 | 1.08 | .280 | 5.747 | 65.202 | .056 | 0.143 | .908 |

| Quality of life | 4 (5) | 546 | 456 | 0.154 | −0.217 | 0.525 | 0.812 | .417 | 13.193 | 77.261 | .004 | 4.182 | .053 |

| Positive symptomsc | 8 (14) | 809 | 828 | 0.078 | −0.126 | 0.283 | 0.749 | .454 | 26.951 | 74.027 | <.001 | 0.367 | .726 |

| Negative symptomsd | 10 (16) | 1231 | 1024 | 0.078 | −0.064 | 0.219 | 1.078 | .281 | 20.719 | 56.559 | .014 | 0.638 | .541 |

| Employment rates | 7 (7) | 1307 | 1247 | 0.025 | −0.124 | 0.173 | 0.324 | .746 | 7.585 | 20.901 | .270 | 0.262 | .804 |

| Depressive symptomse | 3 (3) | 328 | 282 | 0.003 | −0.157 | 0.162 | 0.031 | .975 | 0.059 | 0.000 | .971 | 0.333 | .795 |

Note: aFunctioning was evaluated with the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF),9 the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS)10 or the Global Functioning: Role (GFR); Global Functioning: Social (GFS).11,12

bTotal psychopathology was evaluated with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)2 or the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).4

cPositive symptoms were evaluated with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),2 the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS)3 or the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).4

Fig. 3.

Meta-analytic outcomes of early detection strategies. *Outcomes were rescaled, so that positive results always illustrate favorable outcomes in the intervention group.

Compared to individuals in the control group, individuals in the early detection group had better functioning levels (g = 0.281, 95% CI = 0.073–0.488) at baseline. Total psychopathology (g = 0.186, 95% CI = −0.173 to 0.546), admission rates (g = 0.179, 95% CI = −0.146 to 0.504), quality of life (g = 0.154, 95% CI = −0.217 to 0.525), positive symptoms (g = 0.078, 95% CI = −0.126 to 0.283), negative symptoms (g = 0.078, 95% CI = −0.064 to 0.219), employment rates (g = 0.025, 95% CI = −0.124 to 0.173), and depressive symptoms (g = 0.003, 95% CI = −0.157 to 0.162), did not differ between both groups (table 1, figure 3) (forest plots available in Supplementary figure 1).

Meta-analytic Outcomes of Early Intervention Strategies

Studies reported (in descending order of frequency) on negative symptoms (k = 8, n = 1499), positive symptoms (k = 7, n = 1490), total psychopathology (k = 7, n = 1327), functioning (k = 6, n = 1452), admission rates (k = 5, n = 490), quality of life (k = 4, n = 1061), remission rates (k = 4, n = 821), depressive symptoms (k = 3, n = 393), relapse rates (k = 3, n = 380), and employment rates (k = 3, n = 259) (table 1, figure 4). Compared to the control group, early intervention improved outcomes longitudinally including quality of life (g = 0.600, 95% CI = 0.408–0.791), increased employment rates (g = 0.423, 95% CI = 0.134–0.712), improved negative symptoms (g = 0.417, 95% CI = 0.153–0.682), decreased relapse rates (g = 0.364, 95% CI = 0.117–0.612), reduced hospitalizations (g = 0.335, 95% CI = 0.198–0.468), improved total psychopathology (g = 0.298, 95% CI = 0.014–0.582), improved depressive symptoms (g = 0.268, 95% CI = 0.008–0.528), and improved functioning (g = 0.180, 95% CI = 0.065–0.295) at follow-up. No group differences were found for positive symptoms (g = 0.337, 95% CI = −0.022 to 0.696) and remission rates (g = 0.306, 95% CI = −0.066 to 0.677 corrected to g = 0.180, 95% CI = −0.193, 0.552) (table 2, figure 4) (forest plots available in Supplementary figure 2).

Fig. 4.

Meta-analytic outcomes of early intervention strategies. *Outcomes were rescaled, so that positive results always illustrate favorable outcomes in the intervention group.

Table 2.

Meta-analytic Outcomes of Early Intervention Strategies

| Outcome | k Studies | n INT | n CTRL | Hedges’ g | Z Score | P | Test for Heterogeneity | Egger’s Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | Q | I 2 | P | T Values | P Values | |||||||

| Quality of lifea | 4 (5) | 575 | 486 | 0.600 | 0.408 | 0.791 | 6.146 | <.001 | 3.737 | 19.726 | .291 | 1.890 | .199 |

| Employment rates | 3 (3) | 132 | 127 | 0.427 | 0.135 | 0.718 | 2.869 | .004 | 0.376 | 0.000 | .829 | 0.096 | .939 |

| Negative symptomsb | 8 (13) | 849 | 650 | 0.417 | 0.153 | 0.682 | 3.091 | .002 | 41.017 | 82.934 | <.001 | 0.374 | .721 |

| Relapse rates | 3 (3) | 194 | 186 | 0.366 | 0.117 | 0.616 | 2.882 | .004 | 0.223 | 0.000 | .894 | 0.295 | .817 |

| Positive symptomsc | 7 (12) | 813 | 677 | 0.337 | −0.022 | 0.696 | 1.841 | .066 | 63.406 | 90.537 | <.001 | 0.788 | .466 |

| Admission rates | 5 (5) | 246 | 244 | 0.335 | 0.198 | 0.468 | 4.057 | <.001 | 4.408 | 9.248 | .354 | 3.617 | .036d |

| Remission rates | 4 (4) | 426 | 395 | 0.306 | −0.066 | 0.677 | 1.613 | .107 | 9.772 | 69.300 | .021 | 18.656 | .003e |

| Total psychopathologyf | 7 (10) | 677 | 650 | 0.298 | 0.014 | 0.582 | 2.054 | .040 | 27.990 | 78.564 | <.001 | 0.080 | .939 |

| Depressive symptomsg | 3 (3) | 196 | 197 | 0.268 | 0.008 | 0.528 | 2.019 | .043 | 3.029 | 33.968 | .220 | 3.994 | .156 |

| Functioningh | 6 (7) | 803 | 649 | 0.180 | 0.065 | 0.295 | 3.062 | .002 | 2.155 | 0.000 | .827 | 1.14 | .312 |

Note: aQuality of Life was evaluated with the Quality of Life Scale (QLS),13 the Short Form Health Survey (SF-12)14 or the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHO-QoL).15

bNegative symptoms were evaluated with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)2 or the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS).5

cPositive symptoms were evaluated with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),2 the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS)3 or the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).4

dFunnel plot inspection revealed asymmetry to the right. Due to the lack of small sample bias, we did not adjust our results with the trim-and-fill method.

eFunnel plot inspection revealed asymmetry to the left. Small sample bias was corrected with the trim-and-fill method: to g = 0.180, 95% CI = −0.193 to 0.552.

fTotal psychopathology was evaluated with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)2 or the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).4

Other Non-meta-analytic Outcomes of Early Detection and Intervention Strategies

After implementing early detection strategies, differences were found in the referral patterns,20,40 although not consistently.41 Police referrals decreased by 15.2% (χ2 = 10.5, P = .001),40 while self and family referrals increased by 10.7% (χ2 = 3.5, P = .04)40 in the early detection group. Individuals with FEP in the early detection group were more likely to get clinical care without previous mental health services contact (P = .003).6 Furthermore, early detection services had relatively more patients with affective psychosis (χ2 = 4.011, P = .028),20 and low socioeconomic status (χ2 = 8.659, P = .003),20 whereas premorbid functioning did not differ between the early detection and the control group.42

Regarding early intervention strategies, some studies did not find significant group differences in help-seeking attempts,43 while others found advantages for the intervention vs the control group regarding decreased delay in help-seeking (P = .01)44 and in reaching mental health services (P = .003).44 Moreover, compared to the control group, individuals with FEP in the early intervention group had more friends after 1 year of care (P = .02),45 greater improvements in cognitive symptoms (P < .001),46 and perceived autonomy (P < .01)47 after 2 years, and were less likely to live in supported housing after 5 years (P = .02).48 Compared to the control group, individuals with FEP in the intervention group had lower admission rates and days hospitalized48,49 (although not consistently50), and were less frequently admitted under the Mental Health Act50 or in locked units51 (all P < .05). However, no intervention vs control group differences were found in the rates of police involvement and use of seclusion.51 Individuals in the early intervention vs control group had fewer suicide attempts49 and death by suicide35,49,52 (all P < .05), lower rates of antipsychotics40,53 (particularly first-generation antipsychotics37) and at lower dose,40 with lower maximum initial dosages,54 as well as lower rates of benzodiazepines40 and anticholinergic medications.40 Satisfaction with care was high in the intervention group (3.9/5 for patients and 4/5 for relatives).53 However, family satisfaction, after adjusting for baseline characteristics, was not higher anymore in the intervention vs the control group in one of the included studies.55 In the early intervention vs control group, adherence to comprehensive community care was higher,56 dropout rates lower,55 and mental health service costs were lower 8 years after the early intervention ended (P = .01).34 A summary of the potential additional benefits detected in our systematic review can be found in Supplementary figure 5.

Heterogeneity, Publication Bias, and Meta-regression Analyses

Heterogeneity across the included studies was statistically significant in 5/8 correlates in the early detection group, ranging from 56.6% to 87.9% in those correlates. Meanwhile, heterogeneity was statistically significant in 4/10 outcomes in the intervention group, ranging from 69.3% to 90.5% in those outcomes. Publication bias was not detected in any of the correlates at the time of service contact in the early detection strategies. Heterogeneity was detected in two of the early intervention strategy outcomes, ie, admissions rates (P = .036) and remission rates (P = .003).

Regarding admission rates, funnel plot inspection revealed asymmetry to the right. Due to the lack of small sample bias, we did not adjust results with the trim-and-fill method, and the original value was maintained. Regarding remission rates, funnel plot inspection revealed asymmetry to the left. Small effect bias was thus corrected with the trim-and-fill method, decreasing the effect size from g = 0.306 (CI = −0.066 to 0.677) to g = 0.180 (95% CI = −0.193 to 0.552) (funnel plots available in Supplementary figures 3 and 4).

In meta-regression analyses of DUP, none of the variables evaluated was statistically significant (all P > .05). In meta-regression analyses of early detection correlates, greater efficacy of early detection strategies for the total psychopathology outcome was associated with a higher mean age (β = .124, P = .020), and a lower % of males (β = −.035, P = .024). Greater efficacy of the interventions for quality of life was associated with a higher proportion of individuals with affective psychosis (β = 5.599, P = .011), while greater efficacy for functioning was associated with a higher mean age (β = 0.061, P = .029). There was no significant association between other evaluated moderating factors including DUP, continent, control content, and quality of the studies with other early detection correlates (all P > .05) (Supplementary table 5). For early intervention outcomes, a stronger decrease in the DUP was associated with a greater improvement in the intervention vs control group in quality of life (β = .025, P = .023) but not the severity of positive symptoms (β = −.067, P = .431), negative symptoms (β = .053, P = .151), overall psychopathology (β = .0044, P = .802), functioning (β = .005, P = .530), remission (β = .040, P = .178), or number of subsequent admissions (β = −.014, P = .234). A higher % of males (β = .080, P = .014) was associated with a greater improvement in remission rates. There was no significant association between other evaluated moderating factors with other early intervention outcomes including % affective psychosis, control content, age, or quality of the study (all P > .05) (Supplementary table 6).

Quality Assessment

The quality of the included studies ranged from weak (k = 16, 48.5%) to strong (k = 3, 9.1%). The item most frequently reported as good was data collection (k = 29, 87.9%); The item most frequently reported as poor was blinding (k = 29, 87.9%) (Supplementary figure 6).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to comprehensively evaluate the role of DUP as a treatment target and moderator of early detection and intervention strategies for first-episode psychosis. We aimed to look at the impact of early detection and intervention strategies on both DUP and related real-world outcomes. We described the results from 33 studies narratively and performed different meta-analyses with some of the most clinically relevant and most reported outcomes. We found that the intervention group reduced DUP (g = 0.168) compared to the control group. While from the evaluated variables, the early detection group only had better functioning levels (g = 0.281) at service engagement/baseline than the control group, the early intervention group was able to improve 8/10 outcomes: quality of life (g = 0.600), employment rates (g = 0.423), negative symptoms (g = 0.417), relapse rates (g = 0.364), admission rates (g = 0.335), total psychopathology (g = 0.298), depressive symptoms (g = 0.268), and functioning levels (g = 0.180) compared to the control group.

We evaluated the role of DUP as a determinant of mental health for individuals with FEP. We found that the early detection/intervention group reduced DUP compared to the control group, with a small effect size. Our updated results are somewhat more promising than those from a previous meta-analysis reporting changes in DUP,14 which found similar effect sizes (g = 0.12), but did not detect significant differences between the groups (P > .05). However, these two meta-analyses both suggest that the current impact of early detection strategies on DUP is limited. We believe that there are some individuals with very long DUP,23 that can only reach care with intensive efforts from professionals, which may be a limiting factor that prevents early detection strategies from having a greater impact on DUP. In fact, one of the included studies found that while only 3.4% of the individuals in the control group had very long (>3 years) DUP, this number reached 15.0% in the intervention group (P = .005).24 However, we cannot rule out that some of the strategies may have simply failed in their attempt to reduce DUP in individuals with FEP. In any case, evaluating the impact of the efforts to reduce DUP on mental health outcomes in first-episode psychosis through early detection and intervention strategies is an important indication of their real-world effectiveness. Our results support the implementation of EIS aiming to shorten DUP with both an early detection and intervention component,57 even if the impact on DUP seems limited. It is also possible that robust, comprehensive treatments in FEP improve outcomes regardless of DUP changes. Our superior results of early intervention strategies (improving 8/10 outcomes) compared to early detection strategies would support this hypothesis.

Early detection strategies resulted in better functioning levels at baseline compared to individuals in the control group. However, the groups did not differ regarding total psychopathology, admission rates, quality of life, positive symptoms, negative symptoms, employment rates, and depressive symptoms. One hypothesis would be that early detection may result in individuals entering services prior to more severe functional deterioration. However, although functioning is critical in psychosis and schizophrenia,58 it seems that current detection strategies fail to detect individuals with FEP before more relevant symptoms and other poor outcomes develop. As discussed above, it is possible that the detection of more severely affected individuals that otherwise would have remained without treatment may have played a significant role. However, it is also possible and desirable to refine actual detection strategies. For instance, it seems that information campaigns,59 especially if they are multi-focus60 in nature, can optimize detection strategies. Other strategies, like targeted health education to reduce DUP by helping to better identify signs of mental illness, have also shown promising results,61 since ongoing training correlated with a DUP reduction.61 Barriers to early detection include difficulties in detecting signs of early psychosis,6 worries about stigma or coercive treatment,6 and family difficulties in judging the disease appropriately.62 Moreover, developing local networking activities targeting professionals in the education and primary healthcare sectors may help improve pathways to care.63 A longer DUP has been associated with family members blaming puberty or ideology for the psychosis rather than considering a mental health problem.62 This highlights the importance of outreach strategies and information campaigns in the community. Regarding the best detection strategies to reduce DUP and improve detection correlates, EIS typically provides treatment and support for both individuals experiencing psychosis and individuals who are at high risk of developing psychosis.64 Establishing standalone services for Clinical High Risk for Psychosis (CHR-P) with both an early detection and early detection component seems to be the most effective method for reducing DUP,14 although the amount of available evidence is limited. Detection65 of individuals at CHR-P and early interventions66 directed towards the prevention of psychosis,67 have the potential to maximize the benefits of early interventions in psychosis,3,4 favoring an earlier detection and potentially a reduction in the DUP.

In our meta-analysis, compared to the control group, early interventions improved most clinical outcomes. Previous evidence suggests that EIS, even when these do not have a specific early detection component, can reduce DUP.68 Our results align with a previous meta-analysis that found that EIS was superior to treatment as usual regarding each of the 15 meta-analysed outcomes.4 Although we did not limit the included studies to randomized interventions,4 apart from to those reporting DUP, our effect sizes were similar (small to medium). This finding suggests that the provision of early psychosocial and psychopharmacological interventions is clearly beneficial for individuals with FEP, possibly regardless of DUP. Interestingly, although previous evidence suggests that a delayed start of antipsychotic medication could lead to an increased manifestation and severity of positive symptoms in the long term,69 the early intervention did not have a significant impact on positive symptoms, according to our results. We found that rates and doses of antipsychotics may be lower in the early intervention group,40,53,54 probably in an attempt to minimize side effects.70–72 The effect of this lower antipsychotic rate remains unknown, but recently several meta-analyses have shown that lower than therapeutic antipsychotic doses or dose reduction during maintenance treatment are associated with a higher risk of relapse and hospitalization.73–77 In contrast, the number of studies evaluating remission rates was low (k = 4), limiting our power for this analysis, and the confidence intervals for the remission rates also crossed the null hypothesis line.

In the systematic review, other potential benefits of early detection and early intervention strategies for other outcomes are suggested, although due to limited data, this was not accompanied by meta-analytical evidence. Among these outcomes, a decrease in potentially traumatic experiences, such as police referrals,40 admissions in locked units,51 or admissions under the Mental Health Act,50 could be beneficial, as childhood and adult adversities have shown to be associated with increased psychotic symptoms in individuals with psychotic disorders,78 and increased risk of developing psychosis.79,80 Among the evaluated outcomes, the benefits of EIS on suicide rates35,49,52 and on service users’ satisfaction,53 pivotal to favor engagement and decrease dropout rates, are notable. Finally, from a management, resource allocation, and funding perspective,4 it is relevant that the costs of EIS seem to be lower than the control group costs,34 particularly due to lower inpatient costs.81

According to our results, early detection strategies were more effective in older female individuals for total psychopathology, in individuals with affective psychosis for quality of life, and in older individuals for functioning. Meanwhile, early intervention strategies were more effective in individuals with a more pronounced decrease in DUP for quality of life and in older individuals for remission rates. These findings suggest that some interventions may improve some particular outcomes more easily in individuals with certain characteristics, while in others, achieving this benefit may be more challenging. Precision or personalized medicine considers individual variability when establishing, targeting, and delivering an intervention.82,83 Therefore, the need to stratify interventions according to individual characteristics has been suggested to improve outcomes.84,85 In fact, in early intervention for psychosis, individual characteristics may help detect patient subgroups requiring an adaptation in the duration of the interventions or in its specific content or may suggest the need for higher-intensity interventions.4 The implementation of EIS varies significantly worldwide. For instance, there is almost complete nationwide EIS coverage in Denmark and England, while almost no services are available in many other European countries and low-income countries. It has been suggested that these differences are likely due to local traditions rather than science.57

The current study has several limitations. First, the number of available studies was limited, especially for depressive symptoms and admission rates in the early detection correlates, and for depressive symptoms, relapse rates, and employment rates for early intervention outcomes. Other outcomes (eg, police involvement) were not meta-analysed due to lack of data but included in the systematic review. However, the database was extensive and sufficiently powered to evaluate a broad range of correlates/outcomes. Second, some of the studies had a suboptimal design, including the use of historical control groups due to ethical and implementation reasons. Consequently, 48.5% of the studies had a weak study quality, according to the EPHPP. Particularly, for 87.9% of the included studies, there was no blinding, or this feature was not reported. We conducted meta-regression analyses for both the quality of the studies and the control content and did not find any association between these factors and evaluated correlates/outcomes. Third, we only meta-analysed studies in which DUP for both groups was provided as mean ± SD, as we were not able to pool median DUP following expert statistical advice. Studies using median DUP were included for meta-analytic results of early detection strategies and meta-analytic outcomes of early intervention strategies. However, this approach has allowed us to obtain more homogeneous and comparable measures. Fourth, heterogeneity was significant for DUP and other outcomes, as detailed in the manuscript. Different factors may have influenced the observed heterogeneity, including the setting where the intervention was conducted, and the duration of the intervention. Nevertheless, heterogeneity is common in real-world scenarios, possibly being reflective of our having captured an authentic picture. Fifth, we could not determine for how long it would be appropriate for the interventions to be provided or their differential efficacy for discrete time periods. However, the duration of the intervention did not have a significant impact on any of the outcomes according to the meta-regression analyses. Sixth, we evaluated nineteen outcomes, but we did not apply the multiple-testing correction. Note, as per the Cochrane Handbook, that one in 20 independent statistical tests will be statistically significant at a 5% significance level.86 Seventh, due to heterogeneity and the limited number of included studies, we could not report on the outcomes of specific detection or intervention strategies. Furthermore, all the studies evaluation early intervention outcomes contain early detection components aiming to reduce DUP. Finally, the thresholds regarding DUP varied, and we could not establish the target or minimum reduction of DUP, which would have a specific or threshold impact on mental health outcomes. The definitions of DUP were also different. Notably, defining and reporting DUP presents reliability challenges due to the presence of different levels of insight in patients, blurry borders between attenuated and full psychosis symptoms, and different levels of acuity and severity during the onset of symptoms. However, a meta-analysis of 369 studies found no differences in DUP values according to the definition.87 We conducted additional meta-regression analyses to evaluate any association between the analysed outcomes and various factors, including the continent where the intervention was carried out, % of study participants with affective psychosis, control content, mean participant age, % of males, DUP, and duration of the intervention.

Conclusion

When comparing strategies targeting DUP and control groups, the impact of early detection strategies on DUP and other outcomes is limited. However, the impact of early intervention on the outcomes evaluated, including quality of life, employment, and relapse rates, is significant. Our results support the implementation of EIS with both an early detection and intervention component using robust and comprehensive treatments, even if the impact on DUP is limited. Further research into specific early detection and intervention components using culturally sensitive approaches is required.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at https://academic.oup.com/schizophreniabulletin/.

Contributor Information

Gonzalo Salazar de Pablo, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, UK; Department of Psychosis Studies, Early Psychosis: Interventions and Clinical-detection (EPIC) Lab, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, UK; Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK; Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM, CIBERSAM, Madrid, Spain.

Daniel Guinart, Institut de Salut Mental, Hospital del Mar, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), Barcelona, Spain; Department of Psychiatry, Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute, Barcelona, Spain; Department of Psychiatry, The Zucker Hillside Hospital, Northwell Health, Glen Oaks, NY, USA; Department of Psychiatry and Molecular Medicine, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, NY, USA.

Alvaro Armendariz, Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu, Sant Boi de Llobregat, Spain; Etiopatogenia i Tractament Dels Trastorns Mental Severs (MERITT), Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, Esplugues de Llobregat, Spain.

Claudia Aymerich, Psychiatry Department, Basurto University Hospital, Biocruces Bizkaia Health Research Institute, OSI Bilbao-Basurto, Barakaldo, Bizkaia, Spain.

Ana Catalan, Department of Psychosis Studies, Early Psychosis: Interventions and Clinical-detection (EPIC) Lab, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, UK; Psychiatry Department, Basurto University Hospital, Biocruces Bizkaia Health Research Institute, OSI Bilbao-Basurto, Barakaldo, Bizkaia, Spain.

Luis Alameda, Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, UK; TiPP Program Department of Psychiatry, Service of General Psychiatry, Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland; Department of Psychiatry, Centro Investigación Biomedica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), Instituto de Biomedicina de Sevilla (IBIS), Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, University of Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain.

Maria Rogdaki, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, UK.

Estrella Martinez Baringo, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu de Barcelona, Esplugues de Llobregat, Spain.

Joan Soler-Vidal, FIDMAG Germanes Hospitalàries Research Foundation, Barcelona, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), ISCIII, Barcelona, Spain; Hospital Benito Menni CASM, Hermanas Hospitalarias, Sant Boi de Llobregat, Spain.

Dominic Oliver, Department of Psychosis Studies, Early Psychosis: Interventions and Clinical-detection (EPIC) Lab, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, UK; Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK; NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford, UK; OPEN Early Detection Service, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, UK.

Jose M Rubio, Department of Psychiatry, The Zucker Hillside Hospital, Northwell Health, Glen Oaks, NY, USA; Department of Psychiatry and Molecular Medicine, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, NY, USA; Center for Psychiatric Neuroscience, The Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY, USA.

Celso Arango, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM, CIBERSAM, Madrid, Spain.

John M Kane, Department of Psychiatry, The Zucker Hillside Hospital, Northwell Health, Glen Oaks, NY, USA; Department of Psychiatry and Molecular Medicine, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, NY, USA; Center for Psychiatric Neuroscience, The Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY, USA.

Paolo Fusar-Poli, Department of Psychosis Studies, Early Psychosis: Interventions and Clinical-detection (EPIC) Lab, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, UK; Department of Brain and Behavioral Sciences, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy; OASIS Service, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK; Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre, National Institute for Health Research, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

Christoph U Correll, Department of Psychiatry, The Zucker Hillside Hospital, Northwell Health, Glen Oaks, NY, USA; Department of Psychiatry and Molecular Medicine, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, NY, USA; Center for Psychiatric Neuroscience, The Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY, USA; Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, Germany.

Conflict of interest

Dr Salazar de Pablo has received honoraria from Janssen Cilag and Menarini. Dr. Guinart has been a consultant for and/or has received speaker honoraria from Otsuka, Janssen, Lundbeck and Teva. Dr. Guinart received funding from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CM21/00033). Dr Aymerich has received honoraria from Neuraxpharm. Dr Catalan has received personal fees from Janssen and is supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness. Dr Rubio has received consulting fees from TEVA, Janssen and Karuna, research support from Alkermes, royalties from UpToDate. Dr Alameda has been supportd by the Foundation Adrian and Simone Frutiger and Carigest SA Foundation. Dr Rubio acknowledges NIH grant K23MH127300. Dr Arango has been a consultant to or has received honoraria or grants from Acadia, Angelini, Boehringer, Gedeon Richter, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Minerva, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Sage, Servier, Shire, Schering Plough, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Sunovion and Takeda Dr. Kane has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from: Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cerevel, Click, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, Karuna, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, Merck, Neurocrine, Newron, Otsuka, Reviva, Saladax, Sunovion and Teva. He has received grant support from Lundbeck, Otsuka, Janssen and Sunovion. He is a shareholder of HealthRhythms, LB Pharma, Medincell and The Vanguard Research Group. Dr Fusar-Poli has received research fees from Lundbeck and honoraria from Lundbeck, Angelini, Menarini and Boehringer Ingelheim outside the current study. Prof Correll has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from: AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Aristo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardio Diagnostics, Cerevel, CNX Therapeutics, Compass Pathways, Darnitsa, Denovo, Gedeon Richter, Hikma, Holmusk, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, Karuna, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, MedInCell, Merck, Mindpax, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mylan, Neurocrine, Neurelis, Newron, Noven, Novo Nordisk, Otsuka, Pharmabrain, PPD Biotech, Recordati, Relmada, Reviva, Rovi, Seqirus, SK Life Science, Sunovion, Sun Pharma, Supernus, Takeda, Teva, and Viatris. He provided expert testimony for Janssen and Otsuka. He served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Compass Pathways, Denovo, Lundbeck, Relmada, Reviva, Rovi, Supernus, and Teva. He has received grant support from Janssen and Takeda. He received royalties from UpToDate and is also a stock option holder of Cardio Diagnostics, Mindpax, LB Pharma and Quantic.

References

- 1. Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tandon R, Nasrallah HA, Keshavan MS.. Schizophrenia, “just the facts” 4. Clinical features and conceptualization. Schizophr Res. 2009;110(1–3):1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fusar-Poli P, McGorry PD, Kane JM.. Improving outcomes of first-episode psychosis: an overview. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):251–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Correll CU, Galling B, Pawar A, et al. Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Jama Psychiatry. 2018;75(6):555–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Birchwood M, Todd P, Jackson C.. Early intervention in psychosis—the critical period hypothesis. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lloyd-Evans B, Sweeney A, Hinton M, et al. Evaluation of a community awareness programme to reduce delays in referrals to early intervention services and enhance early detection of psychosis. Bmc Psychiatry. 2015;15:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lynch S, McFarlane WR, Joly B, et al. Early detection, intervention and prevention of psychosis program: community outreach and early identification at six US sites. Psychiatr Serv (Washington, D.C.). 2016;67(5):510–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, Lieberman JA.. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lloyd-Evans B, Crosby M, Stockton S, et al. Initiatives to shorten duration of untreated psychosis: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(4):256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Salazar de Pablo G, Estradé A, Cutroni M, Andlauer O, Fusar-Poli P.. Establishing a clinical service to prevent psychosis: what, how and when? Systematic review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hegelstad WT, Larsen TK, Auestad B, et al. Long-term follow-up of the TIPS early detection in psychosis study: effects on 10-year outcome. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Compton M, Carter T, Bergner E, et al. Defining, operationalizing and measuring the duration of untreated psychosis: advances, limitations and future directions. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2007;1:236–250. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Golay P, Alameda L, Baumann P, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis: impact of the definition of treatment onset on its predictive value over three years of treatment. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;77:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oliver D, Davies C, Crossland G, et al. Can we reduce the duration of untreated psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled interventional studies. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1362–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Penttila M, Jaaskelainen E, Hirvonen N, Isohanni M, Miettunen J.. Duration of untreated psychosis as predictor of long-term outcome in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(2):88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Howes O, Whitehurst T, Shatalina E, et al. The clinical significance of duration of untreated psychosis: an umbrella review and random-effects meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2021;20:75–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Díaz-Caneja CM, Pina-Camacho L, Rodríguez-Quiroga A, Fraguas D, Parellada M, Arango C.. Predictors of outcome in early-onset psychosis: a systematic review. Npj Schizophr. 2015;1:14005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fraguas D, Del Rey-Mejías A, Moreno C, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis predicts functional and clinical outcome in children and adolescents with first-episode psychosis: a 2-year longitudinal study. Schizophr Res. 2014;152(1):130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jonas KG, Fochtmann LJ, Perlman G, et al. Lead-time bias confounds association between duration of untreated psychosis and illness course in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(4):327–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Malla A, Jordan G, Joober R, et al. A controlled evaluation of a targeted early case detection intervention for reducing delay in treatment of first episode psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(11):1711–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lieberman JA, Small SA, Girgis RR.. Early detection and preventive intervention in schizophrenia: from fantasy to reality. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(10):794–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Salazar de Pablo G, Guinart D, Correll CU.. What are the physical and mental health implications of duration of untreated psychosis? Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64(1):e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johannessen JO, McGlashan TH, Larsen TK, et al. Early detection strategies for untreated first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2001;51(1):39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Krstev H, Carbone S, Harrigan SM, Curry C, Elkins K, McGorry PD.. Early intervention in first-episode psychosis—the impact of a community development campaign. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(9):711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P.. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Altman DG, Simera I, Hoey J, Moher D, Schulz K.. EQUATOR: reporting guidelines for health research. Lancet. 2008;371(9619):1149–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. DerSimonian R, Laird N.. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C.. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1997;315(7109):629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lipsey M, Wilson D.. Practical Meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H.. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3 [computer program]. Version. Englewood, NJ: Biostat; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S.. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG.. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(1):12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mihalopoulos C, Harris M, Henry L, Harrigan S, McGorry P.. Is early intervention in psychosis cost-effective over the long term? Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(5):909–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chan SKW, Chan SWY, Pang HH, et al. Association of an early intervention service for psychosis with suicide rate among patients with first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Jama Psychiatry. 2018;75(5):458–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lambert M, Schottle D, Ruppelt F, et al. Early detection and integrated care for adolescents and young adults with psychotic disorders: the ACCESS III study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(2):188–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Keating D, McWilliams S, Boland F, et al. Prescribing pattern of antipsychotic medication for first-episode psychosis: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e040387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chan SKW, Chau EHS, Hui CLM, Chang WC, Lee EHM, Chen EYH.. Long term effect of early intervention service on duration of untreated psychosis in youth and adult population in Hong Kong. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018;12(3):331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Srihari VH, Tek C, Kucukgoncu S, et al. First-episode services for psychotic disorders in the us public sector: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv (Washington, D.C.). 2015;66(7):705–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chong SA, Mythily S, Verma S.. Reducing the duration of untreated psychosis and changing help-seeking behaviour in Singapore. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40(8):619–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Malla A, Norman R, Scholten D, Manchanda R, McLean T.. A community intervention for early identification of first episode psychosis—impact on duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and patient characteristics. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40(5):337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ferrara M, Guloksuz S, Li F, et al. Parsing the impact of early detection on duration of untreated psychosis (DUP): applying quantile regression to data from the Scandinavian TIPS study. Schizophr Res. 2019;210:128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Srihari V, Guloksuz S, Li F, et al. Mindmap: a population-based approach to early detection of psychosis in the United States. Paper presented at: International Congress on Schizophrenia Research, 2017.

- 44. Connor C, Birchwood M, Freemantle N, et al. Don’t turn your back on the symptoms of psychosis: the results of a proof-of-principle, quasi-experimental intervention to reduce duration of untreated psychosis. Bmc Psychiatry. 2016;16:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Larsen TK, Melle I, Friis S, et al. One-year effect of changing duration of untreated psychosis in a single catchment area. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:S128–S132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Melle I, Larsen TK, Haahr U, et al. Prevention of negative symptom psychopathologies in first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(6):634–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Browne J, Penn DL, Bauer DJ, et al. Perceived autonomy support in the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Psychiatr Serv (Washington, D.C.). 2017;68(9):916–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, et al. Five-year follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial of intensive early intervention vs standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):762–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chan SKW, So HC, Hui CLM, et al. 10-Year outcome study of an early intervention program for psychosis compared with standard care service. Psychol Med. 2015;45(6):1181–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Valmaggia LR, Byrne M, Day F, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis and need for admission in patients who engage with mental health services in the prodromal phase. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(2):130–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Petrakis M, Penno S, Oxley J, Bloom H, Castle D.. Early psychosis treatment in an integrated model within an adult mental health service. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(7):483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Melle I, Johannessen JO, Friis S, et al. Course and predictors of suicidality over the first two years of treatment in first-episode schizophrenia spectrum psychosis. Arch Suicide Res. 2010;14(2):158–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cullberg J, Levander S, Holmqvist R, Mattsson M, Wieselgren IM.. One-year outcome in first episode psychosis patients in the Swedish Parachute project. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(4):276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. McGorry PD, Edwards J, Mihalopoulos C, Harrigan SM, Jackson HJ.. EPPIC: an evolving system of early detection and optimal management. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):305–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nishida A, Ando S, Yamasaki S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of comprehensive early intervention care in patients with first-episode psychosis in Japan: 1.5-year outcomes from the J-CAP study. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;102:136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nordentoft M, Albert N.. Early intervention services are effective and must be defended. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):272–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Addington J, Addington D.. Social and cognitive functioning in psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2008;99(1–3):176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Joa I, Johannessen JO, Auestad B, et al. The key to reducing duration of untreated first psychosis: information campaigns. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(3):466–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ly A, Tremblay GA, Beauchamp S.. “What is the efficacy of specialised early intervention in mental health targeting simultaneously adolescents and young adults?” An HTA. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2019;35(2):134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Padilla E, Molina J, Kamis D, et al. The efficacy of targeted health agents education to reduce the duration of untreated psychosis in a rural population. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(2–3):184–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Qiu Y, Li L, Gan Z, et al. Factors related to duration of untreated psychosis of first episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(3):555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Conchon C, Sprüngli-Toffel E, Alameda L, et al. Improving pathways to care for patients at high psychosis risk in Switzerland: PsyYoung study protocol. J Clin Med. 2023;12(14):4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. NHS-England. The National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Implementing the Early Intervention in Psychosis Access and Waiting Time Standard: Guidance. London, UK; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Fusar-Poli P, Sullivan SA, Shah JL, Uhlhaas PJ.. Improving the detection of individuals at clinical risk for psychosis in the community, primary and secondary care: an integrated evidence-based approach. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Davies C, Cipriani A, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Lack of evidence to favor specific preventive interventions in psychosis: a network meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(2):196–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Fusar-Poli P, Salazar de Pablo G, Correll CU, et al. Prevention of psychosis: advances in detection, prognosis, and intervention. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:755–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Singh S. Early intervention in psychosis: much done, much more to do. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):276–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gebhardt S, Schmidt P, Remschmidt H, Hanke M, Theisen FM, König U.. Effects of prodromal stage and untreated psychosis on subsequent psychopathology of schizophrenia: a path analysis. Psychopathology. 2019;52(5):304–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Galling B, Roldán A, Nielsen RE, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in youth exposed to antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Al-Dhaher Z, Kapoor S, Saito E, et al. Activating and tranquilizing effects of first-time treatment with aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in youth. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(5):458–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Carbon M, Kapoor S, Sheridan E, et al. Neuromotor adverse effects in 342 youth during 12 weeks of naturalistic treatment with 5 second-generation antipsychotics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(9):718–727.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Højlund M, Haddad PM, Correll CU.. Limitations in research on maintenance treatment for individuals with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(1):85–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Højlund M, Kemp AF, Haddad PM, Neill JC, Correll CU.. Standard versus reduced dose of antipsychotics for relapse prevention in multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(6):471–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Leucht S, Bauer S, Siafis S, et al. Examination of dosing of antipsychotic drugs for relapse prevention in patients with stable schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(11):1238–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ostuzzi G, Vita G, Bertolini F, et al. Continuing, reducing, switching, or stopping antipsychotics in individuals with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders who are clinically stable: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(8):614–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Luykx JJ, et al. Optimal doses of specific antipsychotics for relapse prevention in a nationwide cohort of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(4):774–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bailey T, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Garcia-Sanchez AM, Hulbert C, Barlow E, Bendall S.. Childhood trauma is associated with severity of hallucinations and delusions in psychotic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(5):1111–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, et al. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(4):661–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Beards S, Gayer-Anderson C, Borges S, Dewey ME, Fisher HL, Morgan C.. Life events and psychosis: a review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(4):740–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Cullberg J, Mattsson M, Levander S, et al. Treatment costs and clinical outcome for first episode schizophrenia patients: a 3-year follow-up of the Swedish “Parachute Project” and Two Comparison Groups. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(4):274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Terry SF. Obama’s precision medicine initiative. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2015;19(3):113–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Genetics Reference. What is precision medicine? https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/precisionmedicine/definition. Accessed June 6, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Fusar-Poli P, Cappucciati M, Borgwardt S, et al. Heterogeneity of psychosis risk within individuals at clinical high risk a meta-analytical stratification. Jama Psychiatry. 2016;73(2):113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Salazar de Pablo G, Catalan A, Fusar-Poli P.. Clinical validity of DSM-5 attenuated psychosis syndrome advances in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Jama Psychiatry. 2020;77(3):311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Higgins J, Green S.. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0; 2011. Cochrane. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Salazar de Pablo G, Aymerich C, Guinart D, et al. What is the duration of untreated psychosis worldwide?—A meta-analysis of pooled mean and median time and regional trends and other correlates across 369 studies. Psychol Med. 2023;13:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.