Dear Editor,

Asparaginase is an essential component in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and its use has been intensified in recent years in treatment protocols across all age groups [1]. Various formulations are available and among these, pegaspargase, a pegylated, E. coli-derived asparaginase, offers a long half-life requiring less frequent dosing together with a lower risk of antibody formation and hypersensitivity reactions [2]. However, the management of pegaspargase-related toxicities might be challenging beyond drug administration due to its pharmacokinetic properties.

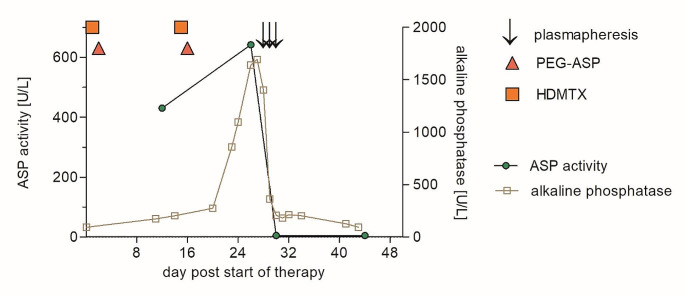

A 57-year-old male with common ALL received consolidation therapy with high-dose methotrexate (days 1 and 15: 1 g/m2) and pegaspargase (days 2 and 16: 1,000 units/m2) within a trial evaluating an age-adapted treatment protocol (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT 03480438, March 21 2018) [3]. The liver function tests (LFTs) slightly increased on day 11 (alkaline phosphatase 1.3x upper limit of normal). Upon further increase of LFTs, ursodeoxycholate was started on day 16 (250 mg qid), but LFTs rapidly increased further (maximum alkaline phosphatase: 13x upper limit of normal). In addition, a high asparaginase activity in the serum was measured on day 27 (642 U/L). Therefore, the decision was made to eliminate asparaginase from the circulation by plasmapheresis. On days 28–30, the patient underwent three sessions with a treated plasma volume of 1.0–1.2 of the calculated total plasma volume, which was replaced by an isotonic albumin solution. The result of this intervention was an immediate decrease of the asparaginase activity down to zero and a rapid and sustained normalisation of LFTs (Fig. 1). The antineoplastic treatment was resumed on day 42, which represents a delay of the scheduled therapy of only 6 days. At present, the patient is in continuous, complete molecular remission of his ALL while receiving maintenance therapy.

Fig. 1.

Clinical course of a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and pegaspargase toxicity. Following consolidation therapy with high-dose methotrexate (HDMTX) and pegaspargase (PEG-ASP) severe liver toxicity occurred in association with high asparaginase (ASP) activity, which vanished with pegaspargase removal by plasmapheresis

Toxicities of asparaginase could affect a variety of organ systems, including the liver, and might be severe and prolonged after pegaspargase. However, extracorporeal drug removal has not been included into proposed treatment algorithms of asparaginase toxicities [4]. Only two patients treated with plasmapheresis for asparaginase liver toxicity have been reported [5, 6]. One patient had received a total dose of 3,750 units pegaspargase, whereas the other patient was treated with 5,000 units/m2 daily of non-pegylated L-asparaginase over 14 days. Both patients improved with plasmapheresis, but the asparaginase activity was not or incompletely monitored. Thus, it remains unclear whether the observed improvements represent a spontaneous course or were due to removal of asparaginase. In our patient, the liver toxicity correlated closely with a high asparaginase activity and rapidly vanished with asparaginase removal and decrease of the enzyme activity down to zero. We therefore advocate that plasmapheresis should be integrated into the treatment algorithms of severe asparaginase toxicities.

Author contributions

M.T., N.G., S.H., U.K. and S.S. contributed to the treatment conception and design. Data collection and analysis were performed by all authors. The first draft of the manuscript was written by M.T. and S.S., and all authors commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare related to the content of this article. MT has received research grants from 3RNetzwerk, Baxter, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft und Forschung, consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kardiologie, Deutsche Hochdruckliga, Medical Tribune, MedPoint, Novartis, Sanofi, and fees as a data safety or advisory board member from Boehringer Ingelheim unrelated to this article. NG has received honoraria from Clinigen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Servier, and fees as a data safety or advisory board member from Clinigen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Servier, unrelated to this article. SH has received travel grants from Sanofi, fees as a data safety or advisory board member from Incyte, Pentixapharm, and is co-founder of the Moonlight AI GmbH, unrelated to this article. UK has received travel grants from Janssen-Cilag, Roche, and research grants from Exscientia Inc., unrelated to this article. SS has received consulting fees from AMGEN, Gilead, Pfizer, Resonance Inc., SERB SAS, honoraria from Akademie für Infektionsmedizin, AMGEN, AvirPharma, CSi Hamburg, Labor28, SERB SAS, Pfizer, travel grants from AMGEN, Gilead, Pfizer, SERB SAS, and fees as a data safety or advisory board member from AMGEN, Gilead, Pfizer, SERB SAS, unrelated to this article.

Informed consent and ethics approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report. Ethical approval for the report of cases is not required by the national regulations or the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Douer D, Gokbuget N, Stock W, Boissel N (2022) Optimizing use of L-asparaginase-based treatment of adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Rev 53:100908. 10.1016/j.blre.2021.100908 10.1016/j.blre.2021.100908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juluri KR, Siu C, Cassaday RD (2022) Asparaginase in the treatment of Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults: current evidence and place in Therapy. Blood Lymphat Cancer 12:55–79. 10.2147/BLCTT.S342052 10.2147/BLCTT.S342052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goekbuget N, Schwartz S, Faul C, Topp MS, Subklewe M, Renzelmann A, Stoltefuss A, Hertenstein B, Wilke A, Raffel S, Jäkel N, Vucinic V, Niemann DM, Reiser L, Serve H, Brüggemann M, Viardot A (2023) Dose reduced chemotherapy in sequence with Blinatumomab for newly diagnosed older patients with Ph/BCR::ABL negative B-Precursor adult lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): preliminary results of the GMALL bold trial. Blood 142(Supplement 1):964–964. 10.1182/blood-2023-180472 10.1182/blood-2023-180472 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pourhassan H, Douer D, Pullarkat V, Aldoss I (2023) Asparaginase: how to better manage toxicities in adults. Curr Oncol Rep 25(1):51–61. 10.1007/s11912-022-01345-6 10.1007/s11912-022-01345-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bilgir O, Calan M, Bilgir F, Cagliyan G, Arslan O (2013) An experience with plasma exchange treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a case with fulminant hepatitis related to L-asparaginase. Transfus Apher Sci 49(2):328–330. 10.1016/j.transci.2013.06.010 10.1016/j.transci.2013.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gopel W, Schnetzke U, Hochhaus A, Scholl S (2016) Functional acute liver failure after treatment with pegylated asparaginase in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: potential impact of plasmapheresis. Ann Hematol 95(11):1899–1901. 10.1007/s00277-016-2773-0 10.1007/s00277-016-2773-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.