Abstract

Background:

Pessaries are an effective treatment for pelvic organ prolapse, yet currently available pessaries can cause discomfort with removal and insertion. An early feasibility trial of an investigational, collapsible pessary previously demonstrated mechanical feasibility during a brief 15-minute office trial. Longer-term, patient-centered safety and efficacy data is needed.

Objectives:

To assess the effectiveness and safety of the investigational vaginal pessary for pelvic organ prolapse at three months.

Study Design:

This was a prospective, seven-center, open-label equivalence study with participants serving as their own controls. Subjects were current users of a Gellhorn or ring pessary with ≥ Stage II prolapse. Baseline subjective and objective data were collected for one month using their current pessary, and then data were collected through a three-month treatment phase with use of the study pessary. The primary outcome was change in Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20 score. Secondary outcome measures included objective assessment of prolapse support, changes in the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-7, and pain with insertion and removal measured on a Visual Analog Scale. Subjects fitted with study pessary were analyzed as intention to treat and those who dropped out were assigned scores at the upper limit of the predefined equivalence limits. Secondary per protocol analyses included subjects who completed treatment. The study was powered to 80% with a minimal important change equivalence limit of 18.3 points on the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20 scale. Square root transformations were used for non-parametric data and p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Results:

Seventy-eight subjects were enrolled, though 16 withdrew prior to study pessary placement. Sixty-two subjects (50 ring and 12 Gellhorn pessary users) were fitted with the study pessary, and 48 (62%) completed the three-month intervention. The change in Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20 scores at three months demonstrated equivalence compared to the subjects’ baseline scores, (mean difference −3.96 (improvement), 90% confidence interval (CI) [−11.99, 4.08], p=0.002). Per protocol analysis of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20, equivalence was not demonstrated with scores favoring the study pessary (mean difference −10.45, 90% CI, [−20.35, 0.54] (p=0.095)). Secondary outcomes included: objective measures of support which were similar, mean difference Ba=0.54 cm, Bp=0.04 cm, favoring study pessary; improvement in mean Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-7 scores for those who completed the trial (pre=32.23, post=16.86, p=0.019); and pain with insertion and removal, which was lower with the study pessary compared to subject’s own pessary (mean difference Visual Analogue Scale insertion=9.91 mm (p=0.019), removal=11.23 mm (p=0.019)). No serious adverse events related to the pessary were reported.

Conclusions:

Equivalence was demonstrated in the study pessary primary outcome compared to current non-collapsible pessaries for change in severity and bother of pelvic floor symptoms. In participants who completed the trial, the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-7 improved with the study pessary and change in Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20 scores were non-equivalent, favoring the study pessary. Subjects reported significantly lower pain scores with both pessary insertion and removal with the novel collapsible pessary compared with their standard pessary.

Keywords: pessary, pelvic organ prolapse, cystocele, apical support, treatment

Tweetable Statement:

A novel, collapsible investigational pessary is equivalent to ring and Gellhorn pessaries in terms of bother of pelvic floor symptoms (PFDI-20 score) and demonstrated improvement in life impact of symptoms (PFIQ-7 score) and reduction in pain during insertion and removal.

Introduction:

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is common, with 40–50% of women having demonstrable prolapse on physical examination.1–3 POP typically becomes symptomatic if the vaginal wall protrudes to the level of the hymen or beyond,4,5 and 3–20% or women seek care for POP in their lifetime. POP management options include watchful waiting, pelvic floor exercises, pessary, and surgery.2

The vaginal pessary is an effective treatment option for POP. Among surveyed urogynecologists, 77% recommend a pessary as first-line treatment for patients with POP.6 Pessaries may be as effective as reconstructive surgery in improving symptoms of POP,7 and many recommend a pessary trial prior to considering surgery.2,8,9 Most pessaries are made of silicone, some with fixed geometry (such as Gellhorn, cube, donut) and others fold or flex (ring). The ring and Gellhorn are the two most used pessaries. Most practitioners, particularly non-urogynecologists, preferentially start with fitting a ring pessary because it is easier for patients and practitioners to use than fixed geometry pessaries.10,11 This is despite findings of equivalence in relieving symptom in a randomized, controlled double-blind study. Gellhorn pessaries more effectively reduce life impact of prolapse symptoms,12 and once fit, have longer continuation rates than the ring with support (10.5 years vs. 1.8 years).13 Additionally, the Gellhorn successfully treated 71% of women at 3 months who failed treatment with the ring with support.5 For patients who do not self-manage their pessaries, many U.S. practitioners recommend surveillance visits 2–4 times annually to avoid preventable complications associated with long term pessary use.2,8,14 Adverse effects have been reported as high as 56%,15 including: discomfort; vaginal erosion, bleeding and discharge; voiding and defecatory dysfunction.16 Pessary self-management may optimally tailor pessary use to specific times of need, such as strenuous activities, while allowing temporary removal for other activities, including intercourse.

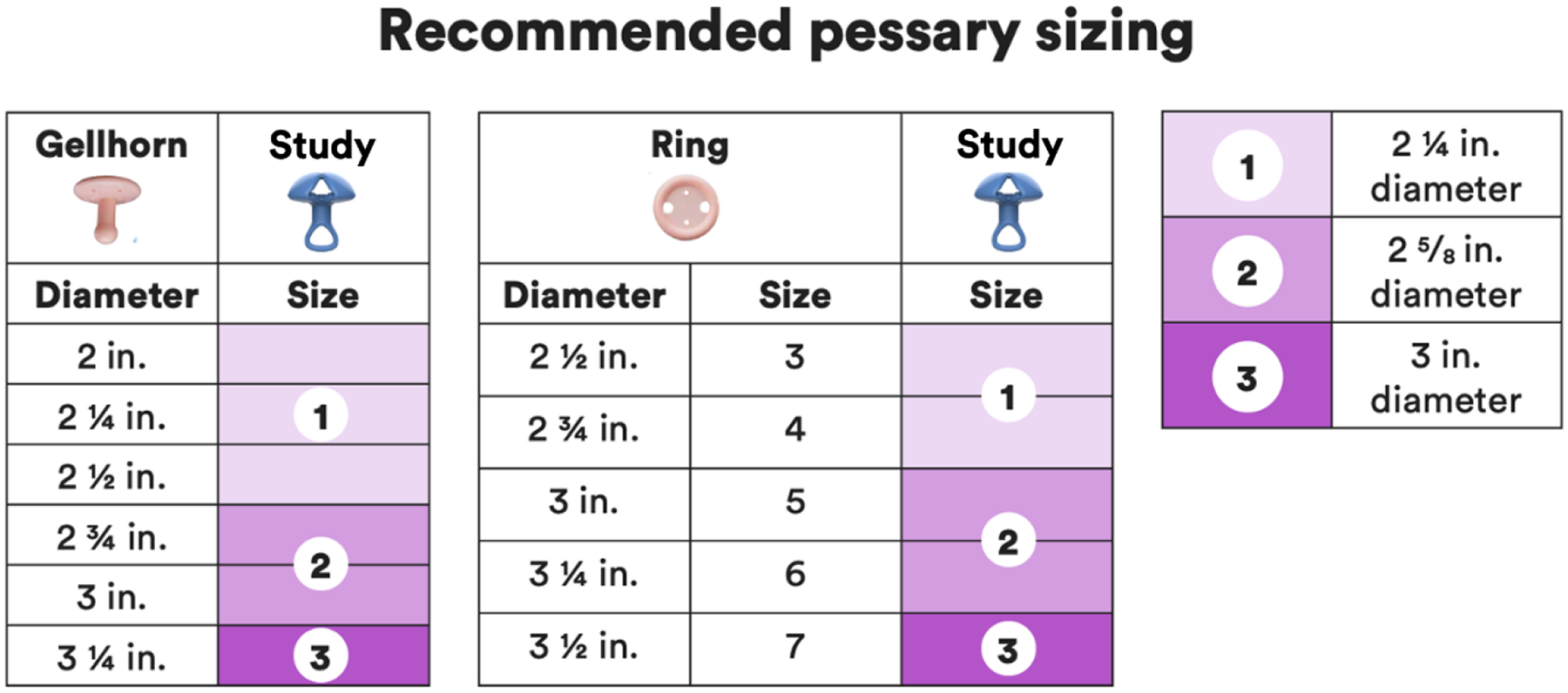

The investigational study pessary [Reia, LLC; Lyme, NH] is engineered with collapsible geometry and a loop removal feature to improve the comfort and ability of pessary removal and reinsertion by physicians and patients.17 The pessary (Fig. 1) is manufactured from medical grade silicone, in three sizes, 57, 67, 76 mm (2 ¼, 25/8, and 3 inches) in diameter, and has a structural form like the Gellhorn. An early feasibility study of the investigational pessary confirmed less patient discomfort with insertion and removal during a 15-minute office trial among current ring and Gellhorn pessary users.17 The objective of the current study is to determine if the investigational pessary is equivalent for treating POP symptom bother compared to traditional pessaries.

Figure 1.

Study pessary in natural resting state (left), when providing support; and in temporary collapsed state (right) during insertion and removal.

Materials and Methods:

This was a prospective, seven-center, open-label equivalence study with participants serving as their own controls. Subjects were current users of a ring or Gellhorn pessary with at least Stage II POP and all provided written consent. Subjects were recruited at seven participating urogynecology clinical trial sites. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained through a central IRB (WIRB-Copernicus Group, Inc., Princeton, NJ) and participating sites’ institutional IRBs. Subjects were compensated for participation with three separate $100 gift cards, totaling $300 if they participated in all study visits. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1. Subjective and objective data were collected for one month using their current pessary, and then through a three-month treatment phase using the study pessary (Fig. 2). The primary outcome was a change in Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20 (PFDI-20) score.18 Secondary outcome measures included objective assessment of prolapse support, changes in the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-7 (PFIQ-7), and pain with insertion and removal using a visual analog scale (VAS), 0–100 millimeters.18

Table 1:

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Women 18 years or older, capable of providing informed consent | Current pregnancy or planning pregnancy in next 6 months |

| Fluency in English or Spanish | Prior treatment failure with pessary. |

| POP-Q Stage II or greater | Vaginal length < 8 cm or subjective narrowing |

Current pessary user for at least 3 months

|

Presence of Current / preexisting:

|

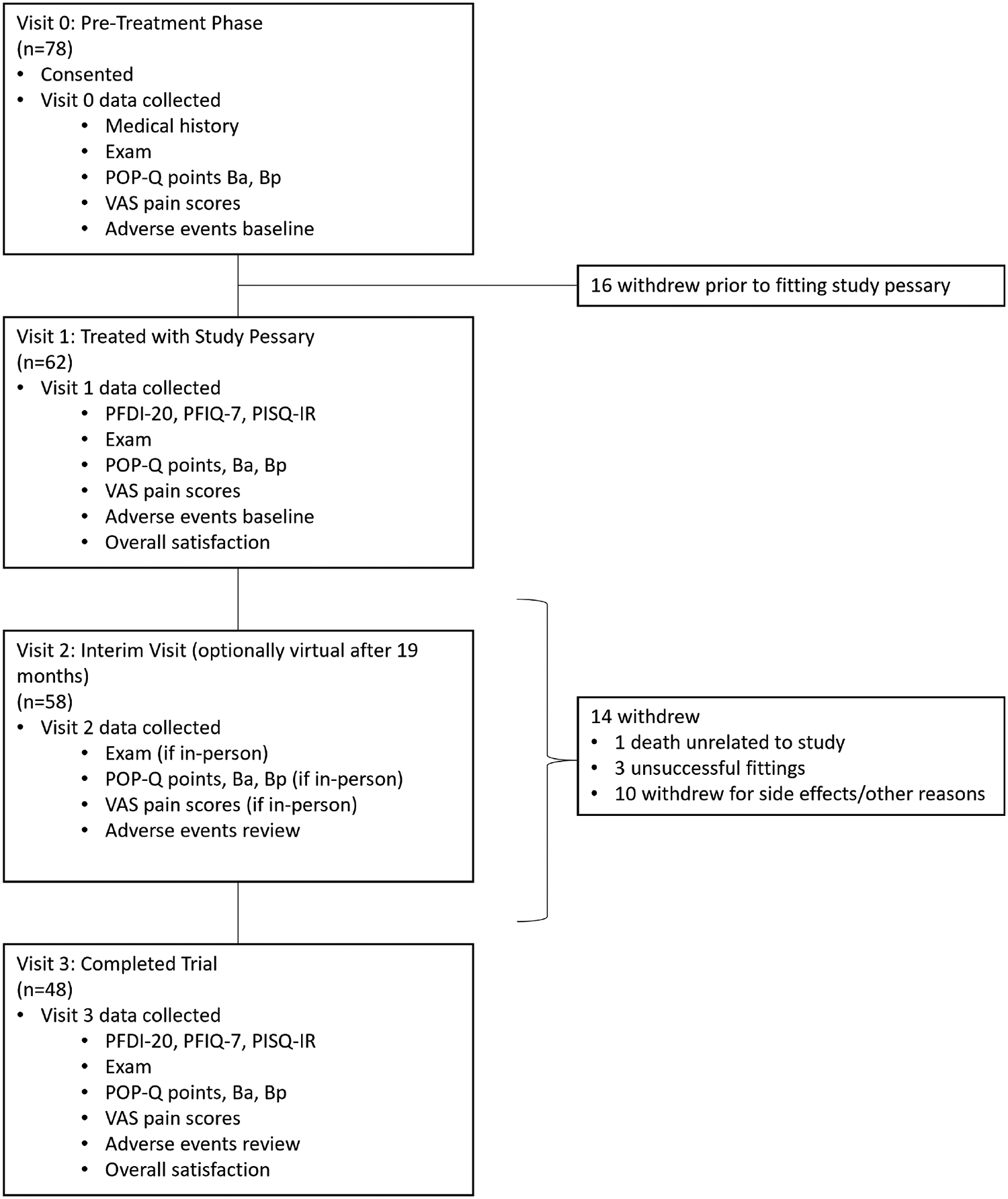

Figure 2.

Flow Diagram

Abbreviations: n = number, POP-Q = Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification, VAS = Visual Analogue Scale (mm), PFDI-20 = Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20, PFIQ-7 = Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire −7, PISQ-IR = Prolapse and Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire.

Baseline data collection (Visit 0) was obtained while the patient was using their current pessary. Visit 0 included: abstracting most recently documented POP-Q examination prior to pessary use, if available; a physical examination; assessment of existing adverse symptoms and objective examination findings. After reinsertion of the current pessary, assessment of prolapse support was measured at the anterior and posterior walls (POP-Q points Ba and Bp). At Visit 1, baseline questionnaires were completed, including the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20 (PFDI-20)18, the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-7 (PFIQ-7)18 and the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA-revised (PISQ-IR).19 The pelvic examination was repeated, and the subject’s current pessary removed. The study pessary was fitted, with the initial fitting based on current pessary size (Fig. 3). Immediately after removal of the current pessary and again after insertion of the study pessary, the patient recorded level of discomfort on a 0–100 mm VAS scale. With the study pessary in place, POP-Q points Ba and Bp were measured. Visit 2 was initially scheduled to evaluate for adverse events and to change the study pessary size, if necessary. The protocol was revised 14 months after study initiation, allowing for a virtual Visit 2 unless the subject was experiencing side effects. At the final visit (Visit 3), questionnaires, VAS scores and examination were repeated. At each scheduled visit, subjects were queried about discomfort with use of the pessary, displacement of the pessary, vaginal or bleeding, the feeling of obstructed urination, and constipation. Adverse events were recorded at each visit, including subjective symptoms and examiner findings. If the subjective symptom and examiner finding matched, such as vaginal discharge reported by the patient and the examiner, this was recorded as one adverse event. Adverse events were classified as Grade 1 or mild (easily tolerated by the subject no intervention necessary), Grade 2 or moderate (causing discomfort or interrupting usual activities), or Grade 3 or severe (causing considerable interference with usual activities, may be incapacitating, or may require hospitalization).20 At each in-person visit, examination was performed to evaluate for perineal tearing, vaginal irritation, vaginal ecchymosis, vaginal abrasions/superficial cuts, deep vaginal erosions, vaginal bleeding, granulation tissue, or copious vaginal discharge. Adverse events were additionally reported by patients and/or observed by practitioners at each additional visit or phone call. At each site, the entire data set was combined in a master file and resolved into unique events, which were then categorized to conform to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) 5.0 definitions.20

Figure 3.

Chart for Initial Sizing and Fitting Study Pessary

Statistical analysis was performed using R, version 4.3.2. Equivalence was evaluated using two one-sided t-tests, each with alpha set at 0.05 to test the composite null hypothesis that the mean difference score between the study and current pessary on the PFDI-20, is between the upper and lower equivalence limits, > 18.3 and < −18.3, respectively. Subjects fitted with study pessary were analyzed as intention to treat. Those who dropped out after any treatment with the study pessary and did not attend Visit 3 did not complete the final PFDI-20 survey. Presuming these data were not missing at random, those subjects were assigned a delta PFDI-20 score of 18.3 (the upper limit of the predefined equivalence limits), disfavoring the study pessary. A sensitivity analysis using missing at random (MAR) based multiple imputation and tipping point analysis was performed to verify treatment of these missing data.

Continuous variables were reported as means (ranges or standard deviations) and medians (ranges) depending on the distribution of data. Categorical data was reported as counts (percentages). Comparisons were made with mean difference and reported as mean difference and 90% confidence interval, using t-test, Wilcoxon and chi-square analysis as indicated. Secondary per protocol analyses included subjects who completed treatment. The study was powered to 80% with a minimal clinically important difference (MCID)21 equivalence limit of 18.3 points on the PFDI-20 scale as described by Wiegersema using a distribution based method.22 Based on our power calculation, we planned recruitment for 40 subjects to ultimately complete the study. Due to anticipated dropouts, 78 were recruited. Square root transformations were used for non-normally distributed data and p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons. Square root transformations on quantitative variables prior to the t-test because they were moderately positively skewed. Non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon test) on the raw data to confirm conclusions.

Results:

Baseline demographic and clinical data are listed in Table 2. Seventy-eight subjects were initially enrolled to start the study (Visit 0), and baseline data were collected (Fig. 2). Sixteen (21%) of the enrolled subjects withdrew prior to trying to fit a study pessary for varying reasons, including unexpected events, such as contracting Covid-19, logistical reasons related to inconvenience of travel, and changing mind about participation. Of the 62 remaining subjects (50 ring and 12 Gellhorn pessary users), 59 (95%) were successfully fitted with the study pessary with a median of one pessary attempt for all subjects successfully fitted. Forty-eight (77%) completed the full three-month trial. Change in PFDI-20 scores at three months demonstrated equivalence compared to subjects’ baseline scores, (mean difference −3.96 (improvement), [CI: −11.99, 4.08], p=0.002). Comparing per protocol analysis of the PDFI-20, equivalence was not demonstrated, with improvement favoring the study pessary (−10.45, [−20.35, 0.54], (p=0.095)). Secondary outcomes are listed in Table 2. Objective measures of support were similar, mean difference Ba=0.5 cm, Bp=0.0 cm, favoring study pessary. Improvement was seen in mean PFIQ-7 scores for those who completed the trial (pre=32.23, post=16.86, p=0.019). Pain with insertion and removal was lower with the study pessary compared to subject’s own pessary (mean difference VAS insertion=9.91 (p=0.019), removal= 11.23 (p=0.019)) (Fig. 4). There were 25 subjects (all ring pessary users) who self-managed their pessary prior to study enrollment and 24 continued to self-manage while using the study pessary. Thirteen subjects started self-managing (9 ring and 4 Gellhorn users) during the study period. Among self-managers, current pessaries were removed a mean of 3.07 (7.36 Standard Deviation (SD)) times per month, compared to 2.57 (SD 4.86) times per month with the study pessary. Vaginal estrogen cream was used in 18 of 48 (37.5%) subjects completing the study. There was no difference in sexual activity or PISQ-IR scores before and during study pessary use. Overall patient satisfaction scores slightly favored the study pessary but were not statistically different. Adverse events are grouped by anatomic location (Table 3). There were higher reported side effects with the study pessary, including symptoms of vaginal discharge, bleeding and odor; and higher rates of physical examination findings of granulation tissue and abrasions. While not specifically collected at each visit, an informal query of the investigators confirmed that the location of abrasions seemed to be predominantly at the apex, rather than at the distal vagina, similar to the location of abrasions that the investigators have noted with traditional pessaries. There were no serious adverse events attributed to the study pessary.

Table 2:

Demographics and baseline clinical characteristics of study group.

| Characteristic | Fitted with Study Pessary (n = 62) |

Completed Study (n=48) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), Mean (SD), [range] | 71.1 (9.04), [28–89] | 71.4 (9.50), [28–89] |

| Parity, Median, [range] | 2 [0–8] | 2 [1–8] |

| BMI, Mean (SD), [range] | 26.6 (4.37), [20–38] | 27.1 (4.34), [21–38] |

| Current pessary type (n, (%)) | ||

| Ring | 50 (80.6) | 38 (79.2) |

| Gellhorn | 12 (20.4) | 10 (20.8) |

| Race (n) | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 1 | 1 |

| Black or African American | 3 | 3 |

| White | 57 | 43 |

| Unknown or not reported | 1 | 1 |

| Ethnicity (n) | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 60 | 46 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 | 2 |

| Concomitant Pelvic Floor Disorders (n, (%)) | ||

| Urinary incontinence | 31 (50%) | 24 (50%) |

| Fecal incontinence | 9 (14.5%) | 6 (12.5%) |

| Prolapse Organ Prolapse Quantification Scores | ||

| Stage, Median, [range] | 3 [2, 4] | 3 [2, 4] |

| Baseline POP-Q evaluations with current pessary in situ (cm), Median [Range] | ||

| Leading edge | 1 [−4, 5.5] | 0 [−4, 5.5] |

| Ba | −2 [−3, 3] | −2 [−3, 3] |

| Bp | −3 [−3, 1] | −3 [−3, 1] |

| Historic POP-Q evaluation before pessary (cm), Median [Range] | ||

| Aa | 1 [−3, 3] | 1 [−3, 3] |

| Ba | 1 [−2, 7] | 2 [−2, 7] |

| C | −3 [−8, 7] | −3.25 [−7, 7] |

| D | −4 [−9, 7] | −5 [−8, 7] |

| TVL | 9 [6.5, 12] | 9 [6.5, 12] |

| Ap | −1.75 [−3, 2] | −1.75 [−3, 2] |

| Bp | −1.5 [−3, 7] | −1.5 [3, 7] |

| GH | 4 [0.5, 7] | 4 [0.5, 7] |

| PB | 3 [0, 5] | 3 [0, 5] |

Abbreviation: POP-Q: Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification

Figure 4.

Pain Scores with insertion / removal of current versus study pessary

Abbreviation: VAS: Visual analog scale (0–100mm)

Table 3:

Primary and secondary outcomes comparing current pessary and study pessary PFDI-20 scores, PFIQ-7 scores, pain with pessary insertion and removal, and support.

| Current Pessary | Study Pessary | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean difference: μstudy – μcurrent (p-value) | Mean difference square root transformation: μstudy – μcurrent (adjusted p-value) | |

| PFDI-20 | 62.75 (42.31) | 62 | 49.46+ (43.20) | 48 | −3.96* (0.0021) | −1.97*^ (0.0005) |

| PFIQ-7 | 32.23 (49.08) | 48 | 16.86 (21.73) | 48 | −15.37* | −1.11*^ (0.019) |

| Pain (VAS Score, 0–100 mm) | ||||||

| Insertion | 23.71 (26.58) | 62 | 13.80 (15.82) | 62 | 9.91* | 0.973*^ (0.019) |

| Removal | 34.27 (30.04) | 53 | 23.04 (25.32) | 53 | 11.23* | 1.172*^ (0.014) |

| POP-Q Point (cm) with pessary in place | ||||||

| Ba | −1.6 (1.31) | 50 | −2.1 (0.95) | 50 | −0.5* | |

| Bp | −2.3 (0.93) | 50 | −2.3 (0.95) | 50 | 0.0* | |

| Global satisfaction VAS score | 69.69 (24.82) | 50 | 72.63 (28.02) | 50 | −2.95* | |

PFDI-20 = Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20, PFIQ-7 = Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-7, SD = standard deviation, n = number, μ = mean, POP-Q = Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification, VAS = Visual Analogue Scale, in mm, range 0–100.

All mean differences favored the study pessary.

Mean calculation based on collected data, dropouts were assigned mean difference values.

The PFIQ-7, pain with insertion, and pain with removal were square root transformed before computing difference scores to minimize skewness.

Comments:

Principle Findings:

In this prospective study it was found that among current ring and Gellhorn pessary users with at least Stage II prolapse, the investigational, collapsible pessary was equivalent to current pessaries with respect to subject symptom and bother relief. There were no serious adverse events attributed to the study pessary, though higher rates mild adverse event such as vaginal discharge, bleeding, abrasions and granulation tissue. The study pessary was less painful to insert and remove and had a greater improvement in pelvic floor symptoms and measures of prolapse support. Most (95%) of subjects were fitted with the first fitting and many subjects were able to learn self-insertion and removal of the study pessary, including those who previously relied on practitioner management.

Results in the Context of What is Known:

It was found that the study pessary demonstrated equivalence for change in PFDI-20 scores and that PFIQ-7 scores were improved compared to the current pessary. Wiegersma established that a MCID on the PFDI-20 of 13.5 – 18.3 points was clinically relevant.22 For this study, we used their suggested more conservative estimate of MCID, 18.3 points. In other studies investigating pessary treatment to pessary-naïve patients, PFDI-20 scores improved by 29.7–51.4 points and PFIQ scores improved by 29.0–42.1 points, comparing pre-treatment to post-treatment after pessary placement.12,23–26 A systematic review and analysis by Sansone26 found improvement in PFDI-20 scores of 46.1 (95% CI [26.8, 65.4]) and PFIQ-7 scores of 36.0 (95% CI [26.0, 46.0]) after an average of 3-months of pessary use compared to scores prior to pessary intervention. Our findings confirm the study pessary is as effective at improving bother of pelvic floors symptoms among current ring and Gellhorn pessary users measured by post-treatment PFDI-20 scores.

Most subjects were successfully fitted with the study pessary on the first attempt. This was not surprising, given that the study population was a select group of established pessary users. Of those fitted, 77% continued with the study pessary over the three-month duration of the study protocol. Among pessary-naïve patients with prolapse, initial fitting is reported to be successful in 41–85.8%.15,27–31 Deng successfully fitted a Gellhorn pessaries in 82.3% of subjects who had failed a trial with a ring pessary, and 70.8% continued to use the Gellhorn pessary at 3 months.30

Chan found that successful pessary use at 12 months correlated with the number of pessaries tried, fewer complications, and an indication of prolapse for pessary-fitting.32 Reported continuation rates in the literature 12 months after pessary fitting ranges from 58–84.9%,13,32–35 with higher rates reported among Gellhorn pessary users, older age, apical prolapse POP-Q Point C > 0, and Genital Hiatus (GH) < 4.33 Wolff reported that factors associated with long-term (mean 7.0 years) use included age > 65 years, estrogen use, and Gellhorn use (mean 10.5 years).13 Other associated factors for pessary discontinuation include vaginal discharge, prior hysterectomy,34 and plans to proceed with surgery. Given that the study pessary is less uncomfortable to remove and insert, it may provide additional opportunity for successful fitting.

Many studies report improvement in bulge symptoms and PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7 scores, but no citations were found regarding anterior and posterior vaginal support measurements (POP-Q points Aa, Ba) with the pessary in place. Ziv et al reported improvement in POP-Q stage with disposable pessary in place.36

Common complications from vaginal pessaries include vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding, discomfort, and urinary and bowel symptoms.37 Similar side effects attributable to pessary, including abrasions, granulation tissue, bleeding, and vaginal discharge were noted in this study. In most cases, discharge is related to inflammation associated with the pessary rather than infection.2 Bleeding can be the consequence of trauma related to pessary insertion or removal, vaginal atrophy with superficial irritation, vaginal erosions, or granulation tissue.2 Vaginal discharge rates have been reported between 23.8–41.5%.25,26,38–40 Out of 62 treated subjects in this trial, 19 experienced persisting, 18 new or worsening, and 8 improving discharge. van der Vaart reported vaginal bleeding due to pessary therapy in 11.5% of 218 subjects.38 By comparison, 19% (12/62) of the current subjects had improving or persisting bleeding while 27% experienced new or worsening bleeding. Hagen and van der Vaart reported vaginal pain in 9.7% and discomfort in 42.7% of their subjects.38,39 Rates of pessary complications in the literature are dependent on definitions used, trial duration, the number of data collection events, and whether the event is reported or observed. This trial is unique in that adverse event data were collected twice in the first month after enrollment with subjects using their current pessary and twice over three months of treatment. While the higher rates of some adverse events observed in this trial compared to the literature could be attributed to sampling frequency, the increased rates of discharge and bleeding seen with use of the study pessary may also be related to its geometry. Regardless, all adverse events related to the study pessary were mild or moderate and within the range of those commonly seen with typical pessary use.

In this trial, 13 subjects dependent on practitioner care for pessary management with their current pessary were able to self-manage with the study pessary, including four Gellhorn users. In a scoping review, Dwyer reported that pessary self-management offers benefits to women in terms of comfort, convenience, perceived access to help and support, and feeling of independence. They found overall complication rates for self-managing women of 10–16%, compared with complication rates of 62% for women receiving clinician-led care. They reported that 70% of self-managing patients remove their pessary usually or always before sexual activitity.41 With these benefits, it is not surprising that 53% of US practitioners offer pessary self-management to their patients.41 Regardless, in a review of 580 long-term pessary users, only 1/3 of patients are able to manage their pessary independently, and patients who use Gellhorn pessaries were far less likely to self-manage than those who use ring pessaries.42 This study pessary may facilitate self-management.

Clinical Implications:

In some form or other, pessaries have been a management option for millennia.37 The lifetime risk for a woman having surgery for POP is 12.6%, or 1:8.43 Composite risks for recurrent apical prolapse within six years have been reported as high as 43– 57%.44 Given that pessaries offer relatively low risk for serious adverse events,2 optimizing pessary care may reduce the number of patients needing surgical treatment. Patients who self-manage pessaries in general report better outcomes,41,45 yet pessary insertion and removal is often related to patient discomfort. As the study pessary has acceptable adverse side effects, with equivalent improvement in bother and symptom relief, it may be a promising alternative due to improved pain with insertion and removal.

Research Implications:

Preliminary findings for the collapsible study pessary are encouraging and additional enhancements and studies are planned. An applicator is being developed for the study pessary to further enable patients’ ability for self-management. This will be studied in a future randomized controlled trial in pessary-naïve women. Additional important next steps include determining the percentage of current pessary users who can learn self-care of their pessaries, and how many primary care practitioners can be taught self-care.41,45–48 Other recent innovations for pessaries include a disposable pessary,36 and 3-D printed “personalized pessaries”.49 Additionally, study of cost-effectiveness and effects on vaginal microbiome may be useful.

Strengths and Limitations:

The strengths of this study include that it is a prospective comparison of the study pessary in a multicenter trial, with subjects as their own controls, using the PDFI-20 and other validated tools to measure effectiveness. Limitations of the study include a relatively high rate of loss of subjects after enrollment before the study pessary was fitted. There were few recruited subjects using Gellhorn pessaries, which typically have higher rates of pain with insertion and removal compared to ring pessaries.

Conclusions:

Equivalence was demonstrated in the study pessary primary outcome compared to current non-collapsible pessaries for change in severity and bother of pelvic floor symptoms. Subjects reported significantly lower pain scores with both pessary insertion and removal with the novel collapsible pessary compared with their standard pessary. The study pessary may facilitate pessary users to increase self-management of their pessaries. Further study is needed to determine if side effects of increased vaginal discharge and bleeding may be reduced with more frequent removal and pessary management.

Supplementary Material

Table 4:

Adverse events reported by patients or examiner.

| Reported Adverse Events | Persistent AE with current and study pessary | New AE and/or worsening with study pessary | Improvement in AE with study pessary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal Symptoms / Signs | |||

| Discharge | 19 | 18 | 8 |

| Bleeding | 8 | 17 | 4 |

| Granulation tissue / abrasions / erosions / ecchymosis | 2 | 30 | 8 |

| Vaginal irritation / burning / pain | 2 | 11 | 5 |

| Odor | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Bulge | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Subtotal Vaginal Symptoms / Signs | 31 | 79 | 27 |

| Pain / Discomfort / Pessary malposition | |||

| Sensation of displacement | 10 | 16 | 10 |

| Pain / Discomfort with use / Pressure | 12 | 17 | 15 |

| Dislodged pessary | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Difficulty reinserting | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Labial irritation | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Pessary rotation causing inability to remove | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Perineal tear | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Subtotal Pain/ Discomfort / Pessary malposition | 23 | 41 | 28 |

| Urinary Symptoms | |||

| Incontinence | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Obstructed urination (subjective and objective) | 3 | 3 | 12 |

| Frequency / urgency | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| UTI | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Subtotal Urinary Symptoms | 5 | 10 | 14 |

| Bowel Symptoms | |||

| Constipation / incomplete defecation | 3 | 4 | 10 |

| Fecal incontinence | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Removal of pessary to enable bowel movement | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Proctitis | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal Bowel Symptoms | 4 | 5 | 11 |

| Total | 70 | 135 | 81 |

Abbreviations: AE = adverse events, UTI = Urinary tract infection

AJOG at a Glance:

A. Why was this study conducted?

This study was conducted to investigate whether a novel, collapsible investigational pessary is a safe and effective option to treat organ prolapse, compared to currently available ring and Gellhorn pessaries.

B. What are the key findings?

The study pessary is effective at supporting prolapse among current ring and Gellhorn pessary users with equivalent change in presence and bother of pelvic floor symptoms measured by post-treatment PFDI-20 scores. Almost all subjects (95%) who attempted fitting with the novel pessary were successful, most on the first attempt. Most participants found the study pessary less painful with insertion and removal but did have increased vaginal discharge and spotting. Many subjects not previously performing self-insertion and removal could do so with the study pessary. There were no serious adverse events related to pessary use.

C. What does this study add to what is already known?

Based on its novel design, the collapsible study pessary may allow more pessary users to self-manage their pessary. Further study is needed to determine if side effects of increased vaginal discharge and bleeding may be reduced with more frequent removal and pessary management.

Financial Support:

Supported by Reia, LLC through a National Institute of Health (NIH) Small Business Administration (SBIR) Grant No. R44HD097809

Disclosures:

All authors other than P.H., P.M.W. received institutional grant support from Reia, LLC for this study.

K.S. is the Chief Editor for WebMD eMedicine, Section of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery and serves on the Board of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons

P.M.W. reports no conflict of interest.

H.E.R: Research Grants: PCORI (Brown University, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center), NIH/NIA (UT Southwestern), NICHD (Univ of Minnesota), NIDDK (Mayo), NICHD (RTI), Renovia, Reia; DSMB Member: BlueWind Medical, Cook Myosite; Royalties: UpToDate; BOD: WorldWide Fistula Fund, SOLACE; Editorial Board: International Urogynecology Journal; Editor: Current Geriatric Reports; Consultant: Neomedic, Coloplast, Palette Life Sciences, COSM, Laborie, Moremme; CME Speaker: Symposia Medicus; Center for Human Genetics, Annual Conference on Obstetrics, Gynecology

C.L.G: Consultant, Provepharm Inc; Expert Witness Johnson and Johnson; Board member, Society for Gynecologic Surgeons

C.R.R.: Research Grants: NICHD (Pelvic Floor Disorders Network), Foundation for Female Health Awareness

P.L.R: Consultant: Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Coloplast; Legal Defense: Boston Scientific, C.R. Bard, Ethicon; Research Support: Caldera, Boston Scientific, Coloplast; Stock Ownership: OriGYN, Northpoint Surgical

M.R.T.: Royalties: Up to Date

G.S.: Speaker’s Bureau for Astellas, Urovant.

P.H. is a co-founder and Chief Medical Officer of Reia, LLC

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Clinical Trial Information:

Date registered: 08/11/2020

Date of initial participant enrollment: 11/22/21

Clinical trial ID: NCT04508335

URL of registration site: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04508335

Data sharing information: Data sharing is not planned for this study.

IRB Protocol Number: 20211208, approval date 4/5/21

Paper Presentation: Accepted for presentation at the 50th Annual Scientific Meeting, Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, Orlando, FL, March 24–26, 2024.

Contributor Information

Kris STROHBEHN, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, NH

Paul M. WADENSWEILER, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, NH

Holly E. RICHTER, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL

Cara L. GRIMES, Westchester Medical Center and New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY

Charles R. RARDIN, Women & Infants Hospital, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI

Peter L. ROSENBLATT, Mount Auburn Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA

Marc R. TOGLIA, Main Line Health, Jefferson Medical College, Media, PA

Gazala SIDDIQUI, Texas Medical Center, University of Texas, Houston, TX

Paul HANISSIAN, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, NH

References:

- 1.Samuelsson EC, Victor FT, Tibblin G, Svärdsudd KF. Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(2 Pt 1):299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung VW, Jeppson P, Madsen A. Nonoperative Management of Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141(4):724–736. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swift SE. The distribution of pelvic organ support in a population of female subjects seen for routine gynecologic health care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(2):277–285. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.107583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber MD, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, et al. Defining Success After Surgery for Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(3):600. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0B013E3181B2B1AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toozs-Hobson P, Swift S. POP-Q stage I prolapse: Is it time to alter our terminology? Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(4):445–446. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2260-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Bump RC, Addison WA. A survey of pessary use by members of the American urogynecologic society. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(6):931–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghanbari Z, Ghaemi M, Shafiee A, et al. Quality of Life Following Pelvic Organ Prolapse Treatments in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2022;11(23). doi: 10.3390/jcm11237166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robert M, Schulz JA, Harvey MA, et al. Technical Update on Pessary Use. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2013;35(7):664–674. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30888-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carberry C, Tulikagas P, Ridgeway BM, Collins SA, Adam RA. American Urogynecologic Society Best Practice Statement: Evaluation and Counseling of Patients with Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23(5):281–287. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemons JL. Vaginal Pessaries: Indications, devices, and approach to selection. UpToDate. Published January 2, 2024. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vaginal-pessaries-indications-devices-and-approach-to-selection?search=vaginalpessaries&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- 11.Pott-Grinstein E, Newcomer JR. Gynecologists’ patterns of prescribing pessaries. J Reprod Med. 2001;46(3):205–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cundiff GW, Amundsen CL, Bent AE, et al. The PESSRI study: symptom relief outcomes of a randomized crossover trial of the ring and Gellhorn pessaries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(4):405.e1–405.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolff B, Williams K, Winkler A, Lind L, Shalom D. Pessary types and discontinuation rates in patients with advanced pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(7):993–997. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-3228-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Propst K, Mellen C, O’Sullivan DM, Tulikangas PK. Timing of Office-Based Pessary Care: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(1):100–105. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarma S, Ying T, Moore KHK. Long-term vaginal ring pessary use: Discontinuation rates and adverse events. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2009;116(13):1715–1721. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02380.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bugge C, Adams EJ, Gopinath D, Reid F. Pessaries (mechanical devices) for pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(2):CD004010. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004010.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strohbehn K, Wadensweiler P, Hanissian P. A novel, collapsible, space-occupying pessary for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2023;34(1):317–319. doi: 10.1007/s00192-022-05415-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barber MD, Walters MD, Bump RC. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers RG, Rockwood TH, Constantine ML, et al. A new measure of sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders (PFD): the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA-Revised (PISQ-IR). Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(7):1091–1103. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-2020-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Department of Heath and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). Published November 27, 2017. Accessed December 31, 2023. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5×11.pdf

- 21.Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status: Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1989;10(4):407–415. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90005-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiegersma M, Kollen BJ, Dekker JH, Berger MY, Panman CMCR, De Vet HCW. Minimal important change in the pelvic floor distress inventory-20 among women opting for conservative prolapse treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;216(4):397.e1–397.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheung RYK, Lee JHS, Lee LL, Chung TKH, Chan SSC. Vaginal Pessary in Women With Symptomatic Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(1):73–80. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mao M, Ai F, Kang J, et al. Successful long-term use of Gellhorn pessary and the effect on symptoms and quality of life in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. Menopause (New York, NY). 2019;26(2):145–151. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao M, Ai F, Zhang Y, et al. Changes in the symptoms and quality of life of women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse fitted with a ring with support pessary. Maturitas. 2018;117:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sansone S, Sze C, Eidelberg A, et al. Role of Pessaries in the Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. In: Obstet Gynecol. Vol 140. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2022:613–622. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mutone MF, Terry C, Hale DS, Benson JT. Factors which influence the short-term success of pessary management of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Tillinghast TA, Jackson ND, Myers DL. Risk factors associated with an unsuccessful pessary fitting trial in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(2):345–350. doi: 10.1016/J.AJOG.2003.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panman CMCR, Wiegersma M, Kollen BJ, Burger H, Berger MY, Dekker JH. Predictors of unsuccessful pessary fitting in women with prolapse: a cross-sectional study in general practice. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(2):307–313. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-3107-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng M, Ding J, Ai F, Zhu L. Successful use of the Gellhorn pessary as a second-line pessary in women with advanced pelvic organ prolapse. Menopause (New York, NY). 2017;24(11):1277–1281. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma C, Xu T, Kang J, et al. Factors associated with pessary fitting in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse: A large prospective cohort study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39:2238–2245. doi: 10.1002/nau.24477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan MC, Hyakutake M, Yaskina M, Schulz JA. What Are the Clinical Factors That Are Predictive of Persistent Pessary Use at 12 Months? J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41(9):1276–1281. doi: 10.1016/J.JOGC.2018.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thys S, Hakvoort R, Milani A, Roovers JP, Vollebregt A. Can we predict continued pessary use as primary treatment in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse (POP)? A prospective cohort study. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32(8):2159–2167. doi: 10.1007/S00192-021-04817-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yimphong T, Temtanakitpaisan T, Buppasiri P, Chongsomchai C, Kanchaiyaphum S. Discontinuation rate and adverse events after 1 year of vaginal pessary use in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(8):1123–1128. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3445-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thys SD, Hakvoort RA, Asseler J, Milani AL, Vollebregt A, Roovers JP. Effect of pessary cleaning and optimal time interval for follow-up: a prospective cohort study. Int Urogynecol J. 31(8):1567–1574. doi: 10.1007/s00192-019-04200-8/Published [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ziv E, Erlich T. A randomized controlled study comparing the objective efficacy and safety of a novel self-inserted disposable vaginal prolapse device and existing ring pessaries. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1252612. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1252612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdulaziz M, Stothers L, Lazare D, Macnab A. An integrative review and severity classification of complications related to pessary use in the treatment of female pelvic organ prolapse. Can Urol Assoc J. 2015;9(5–6):e400–6. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.2783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Vaart LR, Vollebregt A, Milani AL, et al. Effect of Pessary vs Surgery on Patient-Reported Improvement in Patients With Symptomatic Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022;328(23):2312–2323. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.22385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hagen S, Kearney R, Goodman K, et al. Clinical effectiveness of vaginal pessary selfmanagement vs clinic-based care for pelvic organ prolapse (TOPSY): a randomised controlled superiority trial. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102326. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shayo BC, Masenga GG, Rasch V. Vaginal pessaries in the management of symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse in rural Kilimanjaro, Tanzania: a pre-post interventional study. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30(8):1313–1321. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3748-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dwyer L, Dowding D, Kearney R. What is known from the existing literature about selfmanagement of pessaries for pelvic organ prolapse? A scoping review. BMJ Open. 2022;12(7):e060223. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holubyeva A, Rimpel K, Blakey-Cheung S, Finamore PS, O’Shaughnessy DL. Rates of Pessary Self-Care and the Characteristics of Patients Who Perform it. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(3):214–216. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000001013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Jonsson Funk M. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1201–1206. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Unger CA, Barber MD, Walters MD, Paraiso MFR, Ridgeway B, Jelovsek JE. Long-Term Effectiveness of Uterosacral Colpopexy and Minimally Invasive Sacral Colpopexy for Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23(3):188–194. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hagen S, Kearney R, Goodman K, et al. Clinical effectiveness of vaginal pessary self-management vs clinic-based care for pelvic organ prolapse (TOPSY): a randomised controlled superiority trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102326. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kearney R, Brown C. Self-management of vaginal pessaries for pelvic organ prolapse. BMJ Quality Improvement Reports. 2014;3(1):u206180.w2533. doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u206180.w2533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dwyer L, Bugge C, Hagen S, et al. Theoretical and practical development of the TOPSY self-management intervention for women who use a vaginal pessary for pelvic organ prolapse. Trials. 2022;23(1):742. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06681-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dwyer L, Kearney R, Lavender T. A review of pessary for prolapse practitioner training. Br J Nurs. 2019;28(9):S18–S24. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2019.28.9.S18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin YH, Lim CK, Chang SD, Chiang CC, Huang CH, Tseng LH. Tailor-made threedimensional printing vaginal pessary to treat pelvic organ prolapse: a pilot study. Menopause. 2023;30(9):947–953. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.