Abstract

The Rep68 and Rep78 proteins (Rep68/78) of adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV) are critical for AAV replication and site-specific integration. They bind specifically to the AAV inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) and possess ATPase, helicase, and strand-specific/site-specific endonuclease activities. In the present study, we further characterized the AAV Rep68/78 helicase, ATPase, and endonuclease activities by using a maltose binding protein-Rep68 fusion (MBP-Rep68Δ) produced in Escherichia coli cells and Rep78 produced in vitro in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate system. We found that the minimal length of single-stranded DNA capable of stimulating the ATPase activity of MBP-Rep68Δ is 100 to 200 bases. The degree of stimulation correlated positively with the length of single-stranded DNA added to the reaction mixture. We then determined the ATP concentration needed for optimal MBP-Rep68Δ helicase activity and showed that the helicase is active over a wide range of ATP concentrations. We determined the directionality of MBP-Rep68Δ helicase activity and found that it appears to move in a 3′ to 5′ direction, which is consistent with a model in which AAV Rep68/78 participates in AAV DNA replication by unwinding DNA ahead of a cellular DNA polymerase. In this report, we also demonstrate that single-stranded DNA is capable of inhibiting the MBP-Rep68Δ or Rep78 endonuclease activity greater than 10-fold. In addition, we show that removal of the secondary Rep68/78 binding site, which is found only in the hairpin form of the AAV ITR, causes a three- to eightfold reduction in the ability of the ITR to be used as a substrate for the Rep78 or MBP-Rep68Δ endonuclease activity. This suggests that contact between Rep68/78 and this secondary element may play an important role in the Rep-mediated endonuclease activity.

Adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV) is a nonpathogenic human parvovirus which requires the coinfection of an adenovirus or herpesvirus as a helper for its efficient replication (6). AAV has a linear single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) genome of approximately 4.7 kb, flanked by 145-nucleotide inverted terminal repeats (ITRs), important cis elements for viral replication and packaging (15, 49, 50, 57). The AAV genome contains two genes called rep and cap (18, 58). The cap gene encodes proteins called VP-1, VP-2, and VP-3, which form the capsid (8). The rep gene encodes four overlapping in-frame polypeptides referred to as Rep78, Rep68, Rep52, and Rep40 (37, 56). AAV has three promoters in its genome, called p5, p19, and p40 (8). The capsid proteins are encoded by RNA expressed from the p40 promoter, while Rep52 and Rep40 are encoded by RNA expressed from p19 (8). Rep52 and Rep40 play a role in the accumulation of single-stranded progeny genomes used for packaging (9). The Rep78 and Rep68 proteins are encoded by RNA expressed from p5 and are required for viral DNA replication (7, 8). Since Rep68 and Rep78 (Rep68/78) are made from the same open reading frame but from differentially spliced RNA (8), they are nearly identical in both sequence and function (21, 27, 42, 56).

The ITR sequences fold into a T-shaped hairpin structure which serves as a primer for the synthesis of the complementary strand (7, 56). Replication is initiated from the 3′ end of the T-shaped hairpin structure to generate a duplex molecule in which one of the ends is covalently closed. The covalently closed ends are replicated by a process called terminal resolution, which involves a site-specific, strand-specific endonuclease cut at the terminal resolution site (trs) followed by unwinding of the hairpin, so that the end can be replicated (19, 53, 55). This means that part of the initial DNA strand is transferred to the newly synthesized daughter strand. This transfer also results in a change in configuration of several of the ITR internal palindromes relative to each other. These two alternative configurations of the hairpin are referred to as “flip” and “flop” (7). Rep68/78 have ATP-dependent trs endonuclease activity (19, 21), which plays an important role in the terminal resolution process (40, 53). They also have an ATP-dependent DNA helicase activity, whose role in AAV replication is not clear (19, 21).

In addition to trs endonuclease activity and DNA helicase activity, Rep68/78 have a variety of other activities, including the ability to bind to specific sites within the AAV ITR DNA (2, 20, 36, 42, 67), DNA-RNA helicase activity (68), and ATPase activity (68). Im and Muzyczka (21) also showed that Rep68/78 could be retained on a single-stranded DNA agarose column. Rep68/78 also negatively and positively regulate the steady-state levels of mRNA transcribed from the p5, p19, and p40 promoters (5, 27, 28, 30, 34, 43–45). Rep proteins can inhibit or elevate RNA levels from heterologous promoters (17, 29, 69, 71), inhibit cellular transformation by bovine papillomavirus (16) or adenovirus E1a plus an activated ras oncogene (22), and inhibit the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (1, 39, 46). Furthermore, Rep68/78 are thought to be involved in the preferential integration of AAV genomes into a region on the q arm of human chromosome 19 (3, 14, 23–25, 31, 60, 67).

There is strong evidence for the role of the ATP-dependent endonuclease activity of Rep68/78 in AAV replication and site-specific integration (31, 53, 60). Although several steps in AAV replication require DNA unwinding (namely, terminal resolution, reinitiation, and strand displacement synthesis), the role of the Rep68/78 ATP-dependent helicase function in these processes has not been determined. Two lines of evidence suggest that a DNA-unwinding event is required for the trs endonuclease activity. Snyder et al. (54) first noted that if unfilled hairpin, in which the trs is single stranded, is used as the endonuclease substrate, Rep68 no longer requires ATP to nick at the trs and suggested that a requirement for local melting at the trs might be the reason why the Rep68/78 endonuclease activity requires ATP. Second, although several endonuclease-negative, helicase-positive mutants have been created, no helicase-negative, endonuclease-positive mutants have been reported (13, 26, 62, 63). Recently, Zhou et al. (73) reported that Rep68 can unwind a blunt-ended DNA substrate containing a Rep68/78 binding site, such as the one found near the trs.

In this study, we have further characterized the ATPase, DNA helicase, and endonuclease activities of Rep68/78 by using primarily Rep68 protein produced in Escherichia coli as a fusion protein with maltose binding protein (MBP-Rep68Δ), which has previously been shown to also possess these enzymatic activities (10, 68). Previous experiments have demonstrated that MBP-Rep68Δ ATPase activity can be stimulated by single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) (68). In the present study, we conducted experiments to see if there is any correlation between the extent of ATPase activity stimulation and the length of ssDNA. We also determined the directionality of MBP-Rep68Δ helicase activity, which may be helpful in further elucidating AAV replication mechanisms. Additionally, we characterized a sequence element in AAV hairpin DNA which we found to be important for MBP-Rep68Δ and Rep78 endonuclease activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of MBP fusions.

MBP-Rep68Δ (10), MBP-β-galactosidase fusion (MBP-LacZ) (68), and MBP-Rep68ΔNTP (10) were expressed and purified as previously described (10, 68). MBP-Rep68ΔNTP is the same as MBP-Rep68Δ except for a lysine-to-histidine change at Rep68 amino acid 340 (10). Production of the above MBP proteins with predicted molecular weights was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Coomassie blue staining (data not shown). The proteins were quantitated with the bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

In vitro translation.

Rep78 was synthesized with plasmid pMAT4, which encodes wild-type Rep78 (42), and the TNT coupled T7-rabbit reticulocyte lysate in vitro transcription-translation system in 50-μl reaction mixtures, as directed by the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, Wis.). A total of 0.5 μl of in vitro-translated protein in reticulocyte lysate was added per reaction mixture for endonuclease assays. Lysate not programmed with plasmid DNA was used as a negative control.

ATPase assays.

The ATPase assays were conducted by the procedure described by Warrener et al. (65) with modifications as described by Wonderling et al. (68). In a final volume of 10 μl, the reaction mixture contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 3.33 fmol of [α-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol). ssDNA was added, as indicated. Reactions were carried out at 24°C for 1 h and terminated by the addition of EDTA (final concentration, 20 mM). The reaction products were fractionated by thin-layer chromatography. One microliter of the reaction mixture was spotted onto a plastic-backed polyethyleneimine-cellulose sheet (E M Science, Gibbstown, N.J.) and developed by ascending-solvent chromatography in 0.375 M potassium phosphate (pH 3.5). The sheets were dried and autoradiographed. The spots containing the radioactive substrate and product were cut out, and the radioactivity was quantitated by liquid scintillation counting.

Preparation of ssDNA.

M13mp18 ssDNA was cleaved with a high concentration of HaeIII (10 U per μg of DNA), and individual ssDNA fragments with different sizes were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and purified with a gel extraction kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.).

Standard helicase assay.

The DNA helicase substrate, which consisted of a 3′-end-radiolabeled 26-mer oligonucleotide annealed to M13mp18 ssDNA, was prepared by the method of Im and Muzyczka (19). The helicase assays were performed under the conditions described previously (19) with modifications described by Kyöstiö and Owens (26). Briefly, 32P-labeled helicase substrate (25,000 cpm) was incubated with MBP fusions in a 20-μl reaction volume containing 25 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.2 μg of bovine serum albumin (BSA), and different concentrations of ATP. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 24°C, and the reactions were terminated by the addition of 10 μl of gel-loading buffer (0.5% SDS, 50 mM EDTA, 40% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.1% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue, 0.1% [wt/vol] xylene cyanol). The reaction products were resolved by nondenaturing PAGE (6% polyacrylamide) in 1× TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA). The gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film for autoradiography.

Directionality assay for helicase.

The helicase directionality assay was performed by the method of Venkatesan et al. (61) as modified by Matson (32) and including a few additional modifications of our own. To make the directionality substrate, M13mp18 replicative-form double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) was digested with HaeIII and the 341-bp fragment was gel purified. This fragment was mixed with M13mp18 ssDNA and subjected to denaturation and annealing. The resulting partial duplex was digested with ClaI, which cleaves once within the duplex region of the partial duplex and generates DNA duplexes of 200 and 141 bp linked by a 6,059-base single-stranded region. All available 3′-OH termini were labeled with Klenow fragment in the presence of dGTP and [α-32P]dCTP. The reaction mixture was then subjected to phenol-chloroform extraction and passed through a Sepharose CL-4B (Pharmacia) column preequilibrated with a solution containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, and 100 mM NaCl. Individual fractions of 500 μl were collected, and aliquots were examined by nondenaturing PAGE (6% polyacrylamide) and autoradiography. The fractions which contained only the appropriately migrating DNA were pooled and used as the helicase directionality substrate. Reaction conditions were the same as for the standard helicase assay with 0.4 mM ATP.

Preparation of radiolabeled flop AAV hairpin DNA.

Plasmid psub201 (48) was used for preparing hairpin DNA in the flop configuration. psub201 contains a modified AAV genome in which each ITR is flanked by an XbaI site and a PvuII site. The plasmid was digested with XbaI, dephosphorylated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase and 32P 5′-end radiolabeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase. The resulting products were then digested with PvuII, denatured by heating to 100°C for 5 min, and immediately cooled on ice for 4 min to form radiolabeled AAV unfilled hairpin. To make filled hairpin, the unfilled hairpin was treated with Klenow fragment in the presence of deoxynucleoside triphosphates to fill in the 5′ overhang. SmaI digestion (where indicated) was carried out for 1 h at 25°C. DdeI digestion (where indicated) was carried out for 1 h at 37°C. The hairpin DNA was then gel purified.

Preparation of radiolabeled flip AAV hairpin DNA.

AAV hairpin DNA in the flip configuration was derived from AAV no-end DNA. No-end DNA was synthesized by the method of Snyder et al. (55), except that the initial exonuclease III digestion was carried out for 1 min instead of 7 min. No-end DNA contains the AAV genome flanked at either end by covalently closed hairpin DNA in the flip configuration. The hairpins were liberated by XbaI digestion, dephosphorylated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase, and 32P 5′-end radiolabeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase. The hairpins were then treated with Klenow fragment in the presence of deoxynucleoside triphosphates to fill in the 5′ overhang. SmaI digestion (where indicated) was carried out for 1 h at 25°C. DdeI digestion (where indicated) was carried out for 1 h at 37°C. The hairpin DNA was then gel purified.

trs endonuclease assay.

The strand-specific and site-specific endonuclease assay was performed by the method of Im and Muzyczka (19). Radiolabeled (5′ 32P-end-labeled) AAV hairpin DNA (25,000 cpm per reaction) was incubated with MBP-Rep68Δ or in vitro-synthesized Rep78 in a 20-μl final reaction volume containing 25 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 μg of BSA, and 0.4 mM ATP. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C, and the reactions were terminated by the addition of 10 μl of gel-loading buffer (0.5% SDS, 50 mM EDTA, 40% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.1% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue, 0.1% [wt/vol] xylene cyanol) with subsequent boiling to release the nicked fragment. The reaction products were resolved by nondenaturing PAGE (6% polyacrylamide). The gel was then dried and autoradiographed.

Bandshift assays.

Standard bandshift assays were carried out as described previously (20, 67). Briefly, radiolabeled AAV hairpin DNA was incubated at 24°C for 30 min with Rep proteins in a final reaction volume of 20 μl containing 50 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 2% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.5 μg of BSA, 0.01% Nonidet P-40, and 1 μg of poly(dI-dC). The protein-DNA complexes were resolved by nondenaturing PAGE (4% polyacrylamide) at 25 mA with 0.5 × TBE (45 mM Tris-borate, 1 mM EDTA) as the running buffer. The gel was dried and autoradiographed.

For bandshift assays designed to approximate the conditions of the trs endonuclease assay, radiolabeled AAV hairpin DNA was incubated at 24°C for 30 min with Rep proteins in a final reaction volume of 20 μl containing 25 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 μg of BSA, and 0.4 mM adenylyl-imidodiphosphate (a nonhydrolyzable ATP analog). The protein-DNA complexes were resolved by nondenaturing PAGE (4% polyacrylamide) at 25 mA with 0.5× TBE as the running buffer. The gel was dried and autoradiographed.

RESULTS

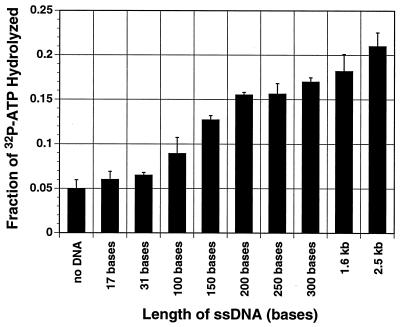

Effects of different-length ssDNAs on MBP-Rep68Δ ATPase activity.

ssDNA was previously demonstrated to stimulate MBP-Rep68Δ ATPase activity (68). In this experiment, we tried to define the minimal length of ssDNA needed to stimulate the ATPase activity. ssDNAs were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. The ATPase assays were conducted in the presence of 60 ng of in vitro-synthesized ssDNA or size-fractionated HaeIII-digested M13mp18 ssDNA. As shown in Fig. 1, the minimal length of ssDNA which stimulates MBP-Rep68Δ ATPase activity is 100 to 200 bases. As the length of ssDNA increases, the ATPase activity increases. For MBP-LacZ, there was no induction of the background ATPase activity with any length of ssDNA (reference 68 and data not shown).

FIG. 1.

The length of added ssDNA is positively correlated with MBP-Rep68Δ ATPase activity. The ATPase activity of MBP-Rep68Δ was determined by incubating 0.25 μg of MBP-Rep68Δ at 24°C for 1 h in a 10-μl reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 3.33 fmol of [α-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol) in the absence or presence of 60 ng of ssDNA of the indicated length (some lengths are approximate since they represent pooled fragments) at 24°C for 1 h. The reaction was terminated by the addition of EDTA (final concentration, 20 mM). The hydrolyzed and nonhydrolyzed radiolabeled ATP were then fractionated by thin-layer chromatography and autoradiographed. The individual dots containing radioactivity were cut out and counted. Each black column represents the mean of three experiments. Error bars indicate the standard error of each mean.

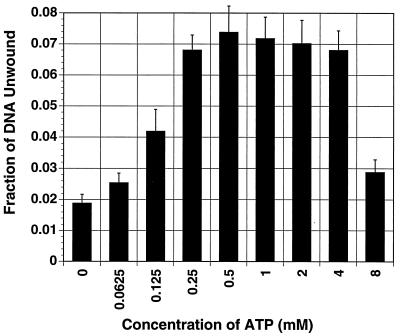

Effects of different ATP concentrations on MBP-Rep68Δ helicase activity.

The initial purpose of doing this experiment was to determine the optimal ATP concentration for Rep68/78 helicase activity, so that we would be able to perform the directionality assay for MBP-Rep68Δ with the optimal concentration. However, as seen in Fig. 2, the helicase activity reaches a plateau at about 0.25 mM ATP and is maximal at ATP concentrations ranging from 0.25 to 4 mM. In the presence of 8 mM ATP, the helicase activity drops dramatically, probably due to the chelation of magnesium ions, which are present at 5 mM.

FIG. 2.

The helicase activity of MBP-Rep68Δ functions over a wide range of ATP concentrations. Experiments were conducted to determine the helicase activity of MBP-Rep68Δ in the absence or presence of indicated concentrations of ATP. The helicase substrate consisted of a radiolabeled 26-mer annealed to M13mp18 ssDNA. The substrate was incubated with 50 ng of MBP-Rep68Δ in a 20-μl reaction volume containing 25 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 1.0 mM DTT, 0.2 μg of BSA, and ATP at the indicated concentrations. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 24°C for 30 min, and the reactions were terminated by the addition of 10 μl of gel loading buffer. The unwound radiolabeled 26-mer and the intact substrate were fractionated by nondenaturing PAGE (6% polyacrylamide). The gel was dried and autoradiographed. The substrate and product bands were cut out and counted. Each black column represents the mean of three experiments. Error bars indicate the standard error of each mean.

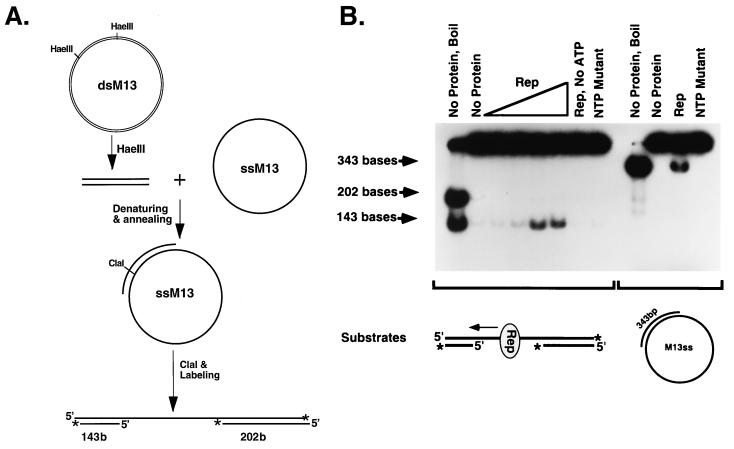

Directionality of MBP-Rep68Δ helicase activity.

Defining how Rep68/78 helicase works in terms of directionality is an essential step toward further understanding the possible roles of the helicase activity of the Rep proteins in the replication process. The directionality of MBP-Rep68Δ helicase was examined by using the directionality substrate as described in Materials and Methods and shown in Fig. 3A. As shown in Fig. 3B, MBP-Rep68Δ catalyzes the unwinding of the 143-base ssDNA from the partially dsDNA substrate but fails to catalyze the unwinding of the 202-base ssDNA from the substrate. In the absence of ATP, there is no unwinding of the fragment, confirming the ATP dependence of the helicase activity. MBP-Rep68ΔNTP, which was included as an additional negative control, also showed no unwinding of the substrate. To exclude the possibility that MBP-Rep68Δ is unable to catalyze the unwinding of ssDNA fragments larger than 143 bases, we included a control in which the 343-bp partial duplex circular DNA as diagrammed in Fig. 3B was used as a helicase substrate under the same conditions. As expected, MBP-Rep68Δ catalyzes the unwinding of the 343-base ssDNA from the circular DNA. These results suggest that MBP-Rep68Δ translocates unidirectionally on ssDNA in a 3′-to-5′ direction.

FIG. 3.

MBP-Rep68Δ has 3′-to-5′ DNA helicase activity. (A) Procedure for making the substrate. (B) Directionality of MBP-Rep68Δ helicase activity. The directionality was determined by incubating MBP-Rep68Δ with the radiolabeled partial duplex substrate, as indicated in the figure, under the helicase reaction conditions described in Materials and Methods. The reaction mixtures contained either no protein or 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, or 4.0 μg of MBP-Rep68Δ (Rep). Reaction mixtures containing 4.0 μg of MBP-Rep68ΔNTP (NTP mutant) or 4.0 μg of MBP-Rep68Δ without ATP (Rep, No ATP) were used as negative controls. A 343-bp partial duplex circular DNA molecule indicated in the figure was used as a control to exclude the possibility that MBP-Rep68Δ is unable to unwind a fragment larger than 143 bases. A 4.0-μg aliquot of MBP-Rep68Δ (Rep) or MBP-Rep68ΔNTP (NTP mutant) was incubated with the 343-bp partial duplex substrate. After the helicase reaction, the products were resolved by nondenaturing PAGE (6% polyacrylamide). The gel was dried and autoradiographed. The reaction mixtures for the lanes marked “No protein, Boil” were heated to 100°C for 5 min. M13ss and ssM13, M13mp18 ssDNA.

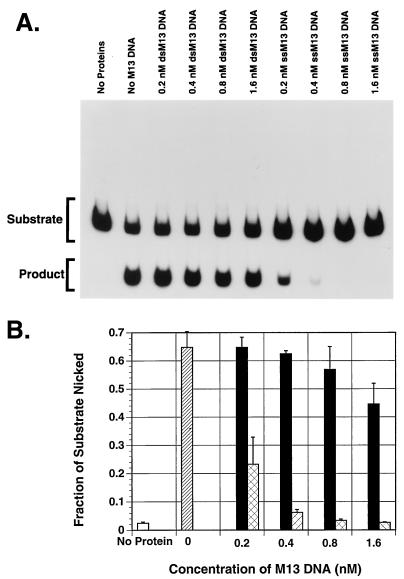

Effect of ssDNA on the endonuclease activity of Rep proteins.

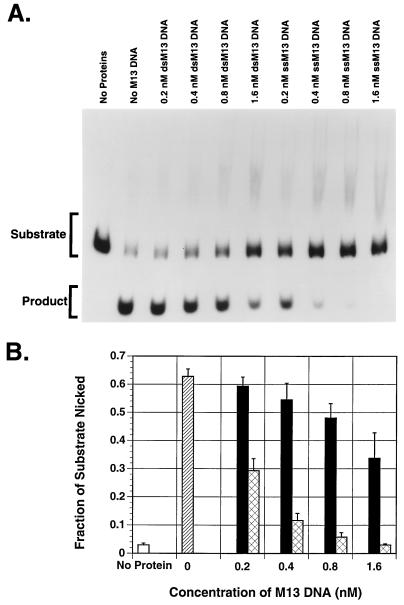

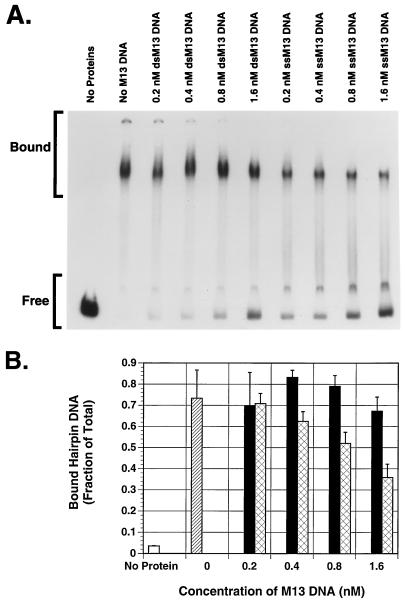

Because of a suspected link between the helicase and endonuclease activities (54), we attempted to perform a time course experiment for both activities of MBP-Rep68Δ simultaneously. For this experiment, we included in a single test tube the AAV hairpin DNA (trs endonuclease substrate) and the standard helicase substrate, consisting of a radiolabeled 26-mer annealed to M13mp18 ssDNA as described in Materials and Methods. We found that the endonuclease activity was greatly reduced (compared to that of a single substrate reaction) at every time point while the helicase activity was as expected (data not shown). We suspected that M13mp18 ssDNA used for the helicase assay in the test tube may exert an inhibitory effect on the endonuclease activity of MBP-Rep68Δ. To test our suspicion further, we examined the endonuclease activity of MBP-Rep68Δ and in vitro-synthesized Rep78 on AAV hairpin DNA in the presence of M13mp18 ssDNA or dsDNA. As seen in Fig. 4 and 5, compared to equal molar amounts of dsDNA, ssDNA inhibits the endonuclease activity of MBP-Rep68Δ and Rep78 up to 10-fold at the highest concentration tested.

FIG. 4.

ssDNA inhibits the MBP-Rep68Δ endonuclease activity. The trs endonuclease activity of MBP-Rep68Δ was determined by incubating 200 ng of MBP-Rep68Δ with 25,000 cpm of 5′-32P-end-labeled flop AAV hairpin DNA per reaction at 37°C for 1 h in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing the indicated concentrations of or M13mp18 ssDNA or dsDNA, 25 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 μg of BSA, and 0.4 mM ATP. The reaction was terminated by addition of gel-loading buffer, and the mixture was boiled for 5 min to release nicked DNA. The nicked DNA (product) and intact hairpin (substrate) were then resolved by PAGE (6% polyacrylamide). The gel was dried and autoradiographed (A). The individual bands were cut out and counted, and the average of three experiments is shown graphically (B). Black columns represent M13mp18 dsDNA-containing samples; cross-hatched columns represent M13mp18 ssDNA-containing samples; the hatched column represents samples with no M13mp18 DNA. The white column represents samples with no Rep protein and no M13mp18 DNA. Error bars indicate the standard error of each mean. ssM13, M13mp18 ssDNA; dsM13, M13mp18 dsDNA.

FIG. 5.

ssDNA inhibits the endonuclease activity of in vitro-synthesized Rep78. The trs endonuclease activity of in vitro-synthesized Rep78 was determined by incubating 0.5 μl of rabbit reticulocyte lysate containing Rep78 with 25,000 cpm of 5′ 32P-end-labeled flop AAV hairpin DNA per reaction at 37°C for 1 h in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing the indicated concentrations of or M13mp18 ssDNA or M13mp18 dsDNA, 25 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 μg of BSA and 0.4 mM ATP. The reaction was terminated by addition of gel loading buffer, and the mixture was boiled for 5 min to release nicked DNA. The nicked DNA (product) and intact hairpin (substrate) were then resolved by PAGE (6% polyacrylamide). The gel was dried and autoradiographed (A). The individual bands were cut out and counted, and the average of three experiments is shown graphically (B). The columns are identified in the legend to Fig. 4. Error bars indicate the standard error of each mean. ssM13, M13mp18 ssDNA; dsM13, M13mp18 dsDNA.

Bandshift assays were performed to investigate if M13mp18 ssDNA inhibits stable binding by MBP-Rep68Δ to AAV hairpin DNA to the same degree. In the bandshift assays, the same amounts of radiolabeled AAV hairpin DNA, MBP-Rep68Δ, and M13mp18 DNA as used in the endonuclease assays were incubated at 24°C for 30 min under standard bandshift assay conditions. The DNA-Rep protein complexes and free DNA were separated by nondenaturing PAGE (4% polyacrylamide). There was a less than twofold decrease in the percentage of AAV hairpin DNA bound by MBP-Rep68Δ in the presence of M13mp18 ssDNA compared with M13mp18 dsDNA or no added DNA (data not shown).

Since the standard bandshift and endonuclease assay conditions are very different from each other, we attempted to approximate the conditions of the endonuclease assay in the context of a bandshift assay (Fig. 6). The same reaction mix as used for the endonuclease reaction was used to incubate hairpin DNA with MBP-Rep68Δ. ATP was replaced with adenylyl-imidodiphosphate in these binding mixes to prevent cleavage of the substrate. We saw an approximately 2-fold drop in the percentage of DNA bound (compared to the no-M13mp18 DNA control) in the presence of the highest concentrations of M13mp18 ssDNA tested, which resulted in a greater than 10-fold reduction in endonuclease activity (Fig. 4).

FIG. 6.

Effect of ssDNA on binding of MBP-Rep68Δ to AAV hairpin DNA. Bandshift assays were performed by incubating 200 ng of MBP-Rep68Δ at 24°C for 30 min with 25,000 cpm of radiolabeled filled AAV hairpin DNA per reaction, and the same concentrations of M13mp18 dsDNA or M13mp18 ssDNA DNA as used in the experiment in Fig. 4 in 20 μl of reaction mixture containing 25 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 μg of BSA, and 0.4 mM adenylyl-imidodiphosphate. The protein-DNA complexes were resolved by nondenaturing PAGE (4% polyacrylamide). The gel was dried and autoradiographed (A). The individual bands were cut out and counted, and the average of three experiments is shown graphically (B). The columns are identified in the legend to Fig. 4. Error bars indicate the standard error of each mean. ssM13, M13mp18 ssDNA; dsM13, M13mp18 dsDNA.

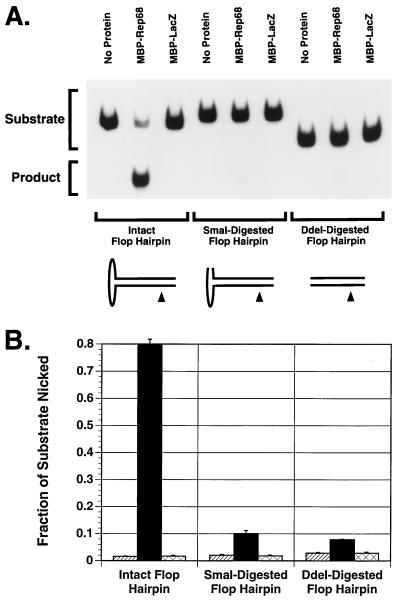

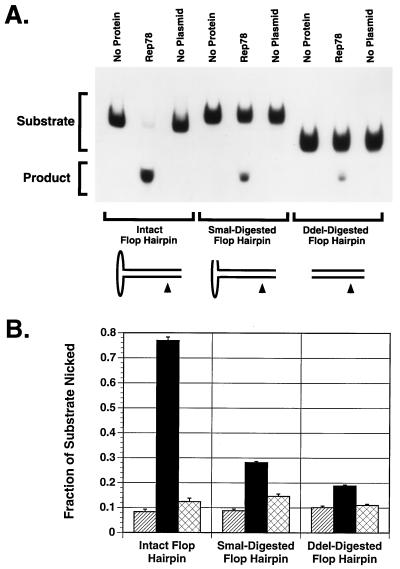

Endonuclease activity of Rep proteins on intact versus SmaI- or DdeI-digested flop hairpin.

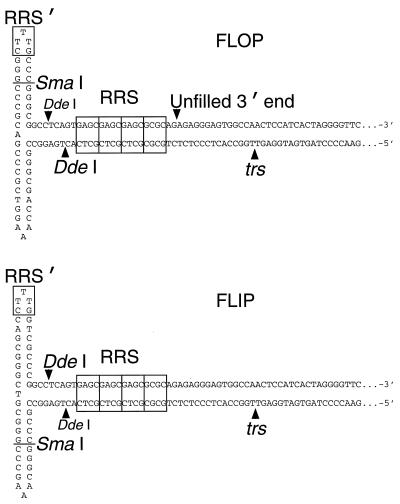

Although the primary Rep recognition sequence (RRS) within the linear portion of the hairpin ITR (Fig. 7) plus a few bases of flanking DNA has been shown to be sufficient for stable Rep68/78 binding (10, 11, 36, 67), a secondary contact, which we call RRS′ (Fig. 7), has been identified at the tip of the hairpin cross-arm furthest from the trs (47). Like the primary RRS, RRS′ is in the same position relative to the trs in either the flip or the flop form of the hairpin (47). Based on indirect evidence, it has been suggested that RRS′ may be important for the Rep68/78 endonuclease activity (47). To test this hypothesis, the 5′-end-radiolabeled hairpin (flop form) was made as described in Materials and Methods and digested with SmaI to remove the secondary binding site. The resulting product was then gel purified and used as a substrate for the endonuclease activity of MBP-Rep68Δ or Rep78. Radiolabeled intact flop hairpin was used as a positive control for these experiments. As shown in Fig. 8 and 9, endonuclease activities of MBP-Rep68Δ and Rep78 on the SmaI-digested flop substrate were reduced by eight- and threefold, respectively, compared with intact flop hairpin, suggesting that the SmaI-removable secondary binding site is indeed an important structural element for Rep68/78 to exert its site-specific and strand-specific endonuclease activity. Digestion of the flop hairpin with DdeI, which removes the entire cross-arm of the hairpin (Fig. 7), resulted in a 10- and 4-fold reduction in endonuclease activity by MBP-Rep68Δ and Rep78, respectively, relative to their activities on the intact flop hairpin (Fig. 8 and 9).

FIG. 7.

Alternate configurations of AAV hairpin terminal repeat DNA substrates. The “flop” configuration is shown at the top, and the “flip” configuration is shown at the bottom. The positions of RRS (67) and RRS′ (47) are shown within the labeled rectangles. The individual imperfect GAGC repeats of the RRS are indicated by subdivisions of its rectangle. The positions of the SmaI and DdeI cut sites, the terminal resolution site (trs) (19), and the 3′ end of unfilled hairpin DNA made from psub201 (48) by PvuII-XbaI digestion and boiling (flop only) are also indicated. The 54-bp stretches at the right end of each substrate sequence are indicated by dots.

FIG. 8.

Effect of SmaI or DdeI digestion of flop hairpin on MBP-Rep68Δ endonuclease activity. All substrates were derived from the same radiolabeling reaction. Radiolabeled flop AAV hairpin was digested with SmaI to remove the secondary binding site for Rep68/78 or with DdeI to remove the entire cross arm. The SmaI-digested, DdeI-digested, or intact flop hairpin (25,000 cpm/reaction) was then incubated with 1.0 μg of MBP-Rep68Δ in a 20-μl trs endonuclease reaction mixture at 37°C for 1 h. The released nicked DNA (product) and intact hairpin (substrate) were then fractionated by PAGE (6% polyacrylamide). The gel was dried and autoradiographed (A). MBP-LacZ (1.0 μg) was used as a negative control. The fraction of substrate nicked is shown as the average of three experiments (B). Hatched columns represent no protein samples, black columns represent MBP-Rep68Δ, and cross-hatched columns represent MBP-LacZ. Error bars indicate the standard error of each mean.

FIG. 9.

Effect of SmaI or DdeI digestion of flop hairpin on the trs endonuclease activity of in vitro-synthesized Rep78. All substrates were derived from the same radiolabeling reaction. Radiolabeled flop AAV hairpin was digested with SmaI to remove the secondary binding site for Rep68/78 or with DdeI to remove the entire cross arm. The SmaI-digested, DdeI-digested, or intact flop hairpin (25,000 cpm/reaction) was then incubated with no protein, 0.5 μl of rabbit reticulocyte lysate containing Rep78, or 0.5 μl of unprogrammed lysate (No Plasmid) in a 20-μl trs endonuclease reaction mixture at 37°C for 1 h. The released nicked DNA (product) and intact substrate were then fractionated by PAGE (6% polyacrylamide). The gel was dried and autoradiographed (A). The fraction of substrate nicked is shown as the average of three experiments (B). Hatched columns represent no-protein samples, black columns represent Rep78-containing lysate, and cross-hatched columns represent unprogrammed lysate. Error bars indicate the standard error of each mean.

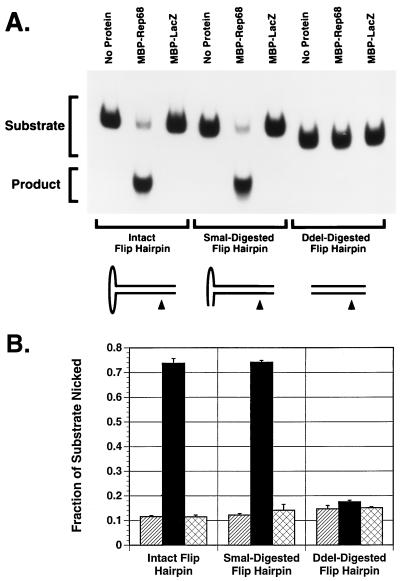

Effects of SmaI and DdeI digestion on flip hairpin as a MBP-Rep68Δ endonuclease substrate.

Snyder et al. (54) previously demonstrated that digestion of the flip hairpin with SmaI had no significant effect on the ability of Rep68 to cleave the hairpin. Figure 10 shows that SmaI digestion did not affect the ability of the flip hairpin to be cleaved by MBP-Rep68Δ. DdeI digestion, however, dramatically reduced this ability. This observation is also consistent with the data of Snyder et al. (54).

FIG. 10.

Effects of SmaI or DdeI digestion of flip hairpin on MBP-Rep68Δ trs endonuclease activity. All substrates were derived from the same radiolabeling reaction. Radiolabeled flip AAV hairpin was digested with SmaI, which does not remove the secondary binding site for Rep68/78, or DdeI, which removes the entire cross arm. The SmaI-digested, DdeI-digested, or intact flip hairpin (25,000 cpm/reaction) was then incubated with 1.0 μg of MBP-Rep68Δ in a 20-μl trs endonuclease reaction mixture at 37°C for 1 h. The released nicked DNA (product) and intact hairpin (substrate) were then fractionated by PAGE (6% polyacrylamide). The gel was dried and autoradiographed (A). MBP-LacZ (1.0 μg) was used as a negative control. The fraction of substrate nicked is shown as the average of three experiments (B). Hatched columns represent no-protein samples, black columns represent MBP-Rep68Δ, and cross-hatched columns represent MBP-LacZ. Error bars indicate the standard error of each mean.

DISCUSSION

The Rep68/78 proteins of AAV possess ATPase, helicase, and endonuclease activities and play an important role in the replication of AAV. In the present study, we have further characterized these Rep68/78 activities by using MBP-Rep68Δ and in vitro-synthesized Rep78. In spite of the presence of the maltose binding domain and a small carboxyl-terminal deletion, MBP-Rep68Δ has performed comparably to wild-type Rep68 in all previous in vitro assays (10, 11, 64). The HindIII site truncation used in the Rep moiety of MBP-Rep68Δ was shown by Owens et al. (42) to have no effect on the performance of unconjugated Rep68/78 protein (produced in human cells) in AAV terminal resolution assays. Chiorini et al. (10, 11) demonstrated that MBP-Rep68Δ cuts the AAV hairpin at exactly the same spot as does wild-type Rep68 purified from infected human cells. They also showed that MBP-Rep68Δ had comparable DNA binding affinity to that of Rep68 produced in human cells. Ward et al. (64) showed that MBP-Rep68Δ could complement uninfected HeLa cell extracts in an in vitro AAV DNA replication system. In this work, we show that the MBP-Rep68Δ endonuclease activity is unaffected by SmaI digestion of the flip form of the hairpin but drastically reduced by DdeI digestion, just as Snyder et al. (54) saw with partially purified Rep68 from HeLa cells infected with adenovirus plus AAV.

We have previously demonstrated that MBP-Rep68Δ has ATPase activity which can be stimulated by ssDNA but not by RNA polymers (68). In this study, we have investigated the relationship between the length of ssDNA and the ATPase activity of MBP-Rep68Δ, a parameter addressing the processivity of AAV Rep proteins on ssDNA. We demonstrated that there is a positive correlation between the length of ssDNA and the extent of the ATPase activity. This property is normally interpreted as indicating that a protein is processive on ssDNA, using ATP as an energy source for translocation (33). We should note that intact M13mp18 ssDNA, a 7.2-kb circle (72), did not stimulate MBP-Rep68Δ ATPase activity any more than the 2.5-kb linear ssDNA did (data not shown), suggesting an intermediate processivity of MBP-Rep68Δ.

Although it is known that a helicase activity is required for AAV replication, it has not been demonstrated conclusively that the helicase activity of the Rep proteins is either necessary or sufficient for DNA unwinding during AAV replication. The problem is that the Rep68/78 endonuclease activity is known to be required for replication. A definitive experiment would require either a helicase-negative, endonuclease-positive Rep mutant or an in vitro replication system containing no cellular helicases. Neither of these have been reported in the literature (13, 26, 62, 63). We believe that identification of the helicase directionality is an important step to further understand Rep68/78 involvement in AAV replication. Since AAV replication requires only leading-strand synthesis (38), a helicase which displaces DNA by translocating along the template strand in a 3′-to-5′ direction should be sufficient. Our data suggest that Rep68/78 are such 3′-to-5′ helicases. Our results are consistent with those of Smith and Kotin (51), who recently reported a 3′-to-5′ directionality for an MBP-AAV Rep52 fusion which also has helicase activity. Rep52 and Rep40 are not required for terminal resolution (40, 53) and normal levels of replicative-form AAV dsDNA can be attained in their absence (9), but they do appear to be required for the generation of progeny ssDNA for packaging. The directionality of MBP-Rep68Δ observed in our study is consistent with a model in which AAV Rep68/78 participates in AAV DNA replication by unwinding DNA while moving in a 3′-to-5′ direction along the template strand ahead of a cellular DNA polymerase.

Our data show that the endonuclease activity of MBP-Rep68Δ is inhibited by ssDNA. This inhibition may provide a selective advantage by preventing Rep68/78 from cleaving off the hairpin DNA packaging signals from the ends of progeny AAV ssDNA destined for encapsidation (7). Our analyses (data not shown) and those of Snyder et al. (54) clearly indicate that partially single stranded hairpin DNA with only a short single-stranded tail can serve as a substrate for the Rep68/78 trs endonuclease activity. We believe this to be a competitive inhibition. Im and Muzyczka (21) showed that Rep68 and Rep78 could bind to ssDNA agarose. Our results show significant inhibition of the endonuclease activity at M13mp18 ssDNA to AAV hairpin DNA molar ratios of approximately 1:8. Our ATPase stimulation results, however, suggest that MBP-Rep68Δ can interact with ssDNA as short as 100 bases, so that the effective ratio of ssDNA binding units to hairpin DNA could be as high as 8:1 (72). Cotmore and Tattersall (12) recently reported a similar inhibition of the nicking activity of the nonstructural protein (NS1) of minute virus of mice, an “autonomous” parvovirus related to AAV, by ssDNA.

Our results indicate that M13mp18 ssDNA greatly inhibited nicking at M13mp18-ssDNA-to-hairpin-DNA ratios which did not greatly reduce the percentage of hairpin molecules bound stably by MBP-Rep68Δ in the bandshift assays. It should, however, be noted that the bandshift assay conditions are different from those of the endonuclease assay. The bandshift experiments may therefore not provide an accurate measure of Rep protein binding under endonuclease assay conditions. It is theoretically impossible for an electrophoretic mobility shift assay to precisely duplicate the conditions of an endonuclease assay. First, in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay, one is actually looking at complexes which are stable for the 1.6-h run time in the gel buffer (0.5× TBE). Second, the addition of ATP results in nicking of the substrate. Im and Muzyczka (19) showed that this can lead to separation of the labeled portion of the hairpin substrate from the portion bound by Rep68, even if the sample is not boiled prior to being loaded onto the gel.

We have, however, attempted to approximate the endonuclease assay conditions by replacing ATP with a nonhydrolyzable ATP analog. The incubation phase of this bandshift assay was performed under the same buffer and salt conditions as the endonuclease assays, and we still see only a small drop in the percentage of hairpin DNA bound when ssDNA is added. This is compared to a dramatic drop in nicking activity at the same ratios of hairpin DNA to Rep protein to ssDNA.

Several models could explain this apparent conflict between the bandshift and endonuclease assay data. The first possibility is that the ability of ssDNA to compete for binding of Rep protein is much greater in the actual endonuclease reaction than under our bandshift conditions. A second possibility is that the Rep molecules that perform the nicking are different from the ones that bind stably at the RRS and RRS′. Batchu and Hermonat (4) reported a mutated Rep protein which had no detectable binding to hairpin DNA but still had detectable although aberrant endonuclease activity. Urabe et al. (59) reported a mutated Rep78 protein with dramatically reduced hairpin binding but normal levels of trs endonuclease activity. Again, the interpretation of these results is confounded by the fact that their endonuclease and DNA binding assays were performed under different conditions.

A third and more supportable hypothesis is that what is actually disrupted by the addition of ssDNA is higher-order Rep protein complexes on hairpin DNA in which some Rep molecules are associated indirectly with DNA via protein-protein interactions which are weaker than the direct protein-DNA interactions. This third interpretation is consistent with multiple observations. Our results also show that at Rep-protein-to-hairpin-DNA ratios at which endonuclease activity is readily detectable, a large portion of the hairpin DNA is bound by MBP-Rep68Δ (Fig. 6 and data not shown). Owens et al. (41) showed that if the hairpin DNA concentration was kept constant and the amount of insect cell nuclear extract containing Rep78 was decreased, the slower-moving (presumably higher-molecular-weight) Rep78-DNA complexes disappeared first. The faster-migrating complexes disappeared first when the DNA concentration was decreased. In the bandshift assays with MBP-Rep68Δ presented here, the protein-DNA complexes trapped in the wells, which we have demonstrated previously to represent specific binding (70), are dramatically reduced by the addition of ssDNA. Since these nonmigrating complexes represent a small portion of the total protein-DNA complexes, their elimination has only a small effect on the percentage of hairpin DNA bound to Rep protein. This model is also consistent with the observation of Zhou et al. (73) that the curve of percentage of DNA nicked versus Rep68 concentration is sigmoid, indicating that cooperativity is required for nicking. The existence of several Rep mutants which are dominant negative for nicking also implies that the active forms of Rep68/78 are multimers (10, 13, 40, 42, 62). It has been demonstrated previously through cross-linking, coimmunoprecipitation, and mixing bandshift experiments that Rep proteins can form multimers in solution and that this multimerization is stimulated by the presence of DNA containing an RRS (13, 52, 66). Additionally, methylation interference analysis of two Rep78-AAV hairpin DNA complexes with different electrophoretic mobilities, which are believed to contain different numbers of Rep78 molecules per complex, showed that the same set of G residues within the DNA was important for the formation of either complex (42). This is again consistent with a model in which some Rep68/78 molecules are held within the protein-DNA complexes primarily by protein-protein interactions.

The primary binding site recognized by Rep68/78 is an imperfect 5′-GAGC-3′ or 5′-GCTC-3′ repeating motif which we call the RRS (10, 67) (Fig. 7). Ryan et al. (47) identified a secondary Rep68/78 binding site, which we call RRS′ (Fig. 7). Snyder et al. (54) performed restriction analysis on AAV hairpin DNA to determine the minimal requirements for an endonuclease substrate, but since their substrate was derived from AAV no-end DNA (54), it was in the flip configuration, in which the SmaI site is at the opposite end of the cross arm from RRS′ (Fig. 7). When they cut their hairpin substrate with SmaI, it had no effect on endonuclease activity (54). We had similar results with our SmaI-digested flip hairpin (Fig. 10). Several groups, however, noted that the linear portion of the ITR is a much less efficient substrate for the Rep68/78 trs endonuclease activity than is the hairpin ITR (11, 35, 54).

Hairpin DNA made by boiling and filling in the PvuII-XbaI fragments of psub201 is in the flop configuration (reference 2 and data not shown). This allowed the precise removal of RRS′ with SmaI digestion. This resulted in a three- to eightfold reduction in cleavage by in vitro-synthesized Rep78 or MBP-Rep68Δ, clearly demonstrating the importance of RRS′.

We also digested both the flip and flop forms of the hairpin with DdeI (which removes the entire cross arm of the hairpin) to confirm that this causes a dramatic decrease in their abilities to be used as Rep endonuclease substrates. This data suggests that the end of the cross arm opposite the trs serves to properly position the Rep protein for efficient nicking or in some other way allows the formation of an optimal protein-DNA complex for nicking.

Finally, there has been some controversy over the use of MBP fusions to analyze Rep68/78 properties. We and others have taken advantage of the MBP moiety to do things such as coimmunoprecipitation assays with an anti-MBP antibody to bring down complexes between MBP-Rep fusions and unconjugated radiolabeled Rep proteins (13, 52). A recent paper by Zhou et al. (73) described studies with Rep68 purified from a baculovirus expression system. Their results and conclusions are nearly identical to the results that we obtained with MBP-Rep68Δ in this work and in previously published work (68). Specifically, they determined that Rep68 is a 3′-to-5′ helicase, that it does not unwind a blunt-ended duplex substrate that does not contain an RRS, that the helicase activity begins to plateau between 0.2 and 0.5 mM ATP, that there is basal ATPase activity in the absence of ssDNA, that NaCl concentrations above 50 mM inhibit Rep68 helicase activity, and that the processivity of Rep68 on ssDNA is between 1 and 2.5 kb.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Robert Kotin and Nancy Nossal for their critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Scotty Walker and Jennifer Fain-Thornton for technical advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antoni B A, Rabson A B, Miller I L, Trempe J P, Chejanovsky N, Carter B J. Adeno-associated virus Rep protein inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 production in human cells. J Virol. 1991;65:396–404. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.396-404.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashktorab H, Srivastava A. Identification of nuclear proteins that specifically interact with adeno-associated virus type 2 inverted terminal repeat hairpin DNA. J Virol. 1989;63:3034–3039. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3034-3039.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balagué C, Kalla M, Zhang W W. Adeno-associated virus Rep78 protein and terminal repeats enhance integration of DNA sequences into the cellular genome. J Virol. 1997;71:3299–3306. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3299-3306.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batchu R B, Hermonat P L. Disassociation of conventional DNA binding and endonuclease activities by an adeno-associated virus Rep78 mutant. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;210:717–725. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaton A, Palumbo P, Berns K I. Expression from the adeno-associated virus p5 and p19 promoters is negatively regulated in trans by the Rep protein. J Virol. 1989;63:4450–4454. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4450-4454.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter B J. Adeno-associated virus helper functions. In: Tijssen P, editor. Handbook of parvoviruses. I. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 255–282. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter B J, Mendelson E, Trempe J P. AAV DNA replication, integration, and genetics. In: Tijssen P, editor. Handbook of parvoviruses. I. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 169–226. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter B J, Trempe J P, Mendelson E. Adeno-associated virus gene expression and regulation. In: Tijssen P, editor. Handbook of parvoviruses. I. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 227–254. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chejanovsky N, Carter B J. Mutagenesis of an AUG codon in the adeno-associated virus rep gene: effects on viral DNA replication. Virology. 1989;173:120–128. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiorini J A, Weitzman M D, Owens R A, Urcelay E, Safer B, Kotin R M. Biologically active Rep proteins of adeno-associated virus type 2 produced as fusion proteins in Escherichia coli. J Virol. 1994;68:797–804. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.797-804.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiorini J A, Wiener S M, Owens R A, Kyöstiö S R M, Kotin R M, Safer B. Sequence requirements for stable binding and function of Rep68 on the adeno-associated virus type 2 inverted terminal repeats. J Virol. 1994;68:7448–7457. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7448-7457.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cotmore S F, Tattersall P. High-mobility group 1/2 proteins are essential for initiating rolling-circle-type DNA replication at a parvovirus hairpin origin. J Virol. 1998;72:8477–8484. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8477-8484.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis M D, Wonderling R S, Walker S L, Owens R A. Analysis of the effects of charge cluster mutations in adeno-associated virus Rep68 protein in vitro. J Virol. 1999;73:2084–2093. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2084-2093.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giraud C, Winocour E, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus is directed by a cellular DNA sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10039–10043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauswirth W W, Berns K I. Origin and termination of adeno-associated virus DNA replication. Virology. 1977;78:488–499. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(77)90125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermonat P L. The adeno-associated virus Rep78 gene inhibits cellular transformation induced by bovine papillomavirus. Virology. 1989;172:253–261. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hermonat P L. Inhibition of H-ras expression by the adeno-associated virus Rep78 transformation suppressor gene product. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3373–3377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hermonat P L, Labow M A, Wright R, Berns K I, Muzyczka N. Genetics of adeno-associated virus: isolation and preliminary characterization of adeno-associated virus type 2 mutants. J Virol. 1984;51:329–339. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.2.329-339.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Im D S, Muzyczka N. The AAV origin binding protein Rep68 is an ATP-dependent site-specific endonuclease with DNA helicase activity. Cell. 1990;61:447–457. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90526-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Im D S, Muzyczka N. Factors that bind to adeno-associated virus terminal repeats. J Virol. 1989;63:3095–3104. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3095-3104.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Im D S, Muzyczka N. Partial purification of adeno-associated virus Rep78, Rep52, and Rep40 and their biochemical characterization. J Virol. 1992;66:1119–1128. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.1119-1128.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khleif S N, Myers T, Carter B J, Trempe J P. Inhibition of cellular transformation by the adeno-associated virus rep gene. Virology. 1991;181:738–741. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90909-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotin R M, Linden R M, Berns K I. Characterization of a preferred site on human chromosome 19q for integration of adeno-associated virus DNA by non-homologous recombination. EMBO J. 1992;11:5071–5078. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotin R M, Menninger J C, Ward D C, Berns K I. Mapping and direct visualization of a region-specific viral DNA integration site on chromosome 19q13-qter. Genomics. 1991;10:831–834. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90470-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotin R M, Siniscalco M, Samulski R J, Zhu X, Hunter L, Laughlin C A, McLaughlin S, Muzyczka N, Rocchi M, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2211–2215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kyöstiö S R M, Owens R A. Identification of mutant adeno-associated virus Rep proteins which are dominant-negative for DNA helicase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;220:294–299. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kyöstiö S R M, Owens R A, Weitzman M D, Antoni B A, Chejanovsky N, Carter B J. Analysis of adeno-associated virus (AAV) wild-type and mutant Rep proteins for their abilities to negatively regulate AAV p5 and p19 mRNA levels. J Virol. 1994;68:2947–2957. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2947-2957.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyöstiö S R M, Wonderling R S, Owens R A. Negative regulation of the adeno-associated virus (AAV) P5 promoter involves both the P5 Rep binding site and the consensus ATP-binding motif of the AAV Rep68 protein. J Virol. 1995;69:6787–6796. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6787-6796.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labow M A, Graf L H, Jr, Berns K I. Adeno-associated virus gene expression inhibits cellular transformation by heterologous genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:1320–1325. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.4.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Labow M A, Hermonat P L, Berns K I. Positive and negative autoregulation of the adeno-associated virus type 2 genome. J Virol. 1986;60:251–258. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.1.251-258.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linden R M, Winocour E, Berns K I. The recombination signals for adeno-associated virus site-specific integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7966–7972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matson S W. Escherichia coli helicase II (uvrD gene product) translocates unidirectionally in a 3′ to 5′ direction. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:10169–10175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matson S W, Kaiser-Rogers K A. DNA helicases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:289–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCarty D M, Christensen M, Muzyczka N. Sequences required for coordinate induction of adeno-associated virus p19 and p40 promoters by Rep protein. J Virol. 1991;65:2936–2945. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.2936-2945.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCarty D M, Pereira D J, Zolotukhin I, Zhou X, Ryan J H, Muzyczka N. Identification of linear DNA sequences that specifically bind the adeno-associated virus Rep protein. J Virol. 1994;68:4988–4997. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4988-4997.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCarty D M, Ryan J H, Zolotukhin S, Zhou X, Muzyczka N. Interaction of the adeno-associated virus Rep protein with a sequence within the A palindrome of the viral terminal repeat. J Virol. 1994;68:4998–5006. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4998-5006.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendelson E, Trempe J P, Carter B J. Identification of the trans-acting Rep proteins of adeno-associated virus by antibodies to a synthetic oligopeptide. J Virol. 1986;60:823–832. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.3.823-832.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ni T H, McDonald W F, Zolotukhin I, Melendy T, Waga S, Stillman B, Muzyczka N. Cellular proteins required for adeno-associated virus DNA replication in the absence of adenovirus coinfection. J Virol. 1998;72:2777–2787. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2777-2787.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oelze I, Rittner K, Sczakiel G. Adeno-associated virus type 2 rep gene-mediated inhibition of basal gene expression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 involves its negative regulatory functions. J Virol. 1994;68:1229–1233. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.1229-1233.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Owens R A, Carter B J. In vitro resolution of adeno-associated virus DNA hairpin termini by wild-type Rep protein is inhibited by a dominant-negative mutant of Rep. J Virol. 1992;66:1236–1240. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.1236-1240.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Owens R A, Trempe J P, Chejanovsky N, Carter B J. Adeno-associated virus Rep proteins produced in insect and mammalian expression systems: wild-type and dominant-negative mutant proteins bind to the viral replication origin. Virology. 1991;184:14–22. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90817-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Owens R A, Weitzman M D, Kyöstiö S R M, Carter B J. Identification of a DNA-binding domain in the amino terminus of adeno-associated virus Rep proteins. J Virol. 1993;67:997–1005. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.997-1005.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pereira D J, McCarty D M, Muzyczka N. The adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep protein acts as both a repressor and an activator to regulate AAV transcription during a productive infection. J Virol. 1997;71:1079–1088. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1079-1088.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pereira D J, Muzyczka N. The adeno-associated virus type 2 p40 promoter requires a proximal Sp1 interaction and a p19 CArG-like element to facilitate Rep transactivation. J Virol. 1997;71:4300–4309. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4300-4309.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pereira D J, Muzyczka N. The cellular transcription factor Sp1 and an unknown cellular protein are required to mediate Rep protein activation of the adeno-associated virus p19 promoter. J Virol. 1997;71:1747–1756. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1747-1756.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rittner K, Heilbronn R, Kleinschmidt J A, Sczakiel G. Adeno-associated virus type 2-mediated inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication: involvement of p78rep/p68rep and the HIV-1 long terminal repeat. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:2977–2981. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-11-2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryan J H, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N. Sequence requirements for binding of Rep68 to the adeno-associated virus terminal repeats. J Virol. 1996;70:1542–1553. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1542-1553.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samulski R J, Chang L S, Shenk T. A recombinant plasmid from which an infectious adeno-associated virus genome can be excised in vitro and its use to study viral replication. J Virol. 1987;61:3096–3101. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3096-3101.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samulski R J, Srivastava A, Berns K I, Muzyczka N. Rescue of adeno-associated virus from recombinant plasmids: gene correction within the terminal repeats of AAV. Cell. 1983;33:135–143. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Senapathy P, Tratschin J D, Carter B J. Replication of adeno-associated virus DNA. Complementation of naturally occurring rep− mutants by a wild-type genome or an ori− mutant and correction of terminal palindrome deletions. J Mol Biol. 1984;179:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith R H, Kotin R M. The Rep52 gene product of adeno-associated virus is a DNA helicase with 3′-to-5′ polarity. J Virol. 1998;72:4874–4881. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4874-4881.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith R H, Spano A J, Kotin R M. The Rep78 gene product of adeno-associated virus (AAV) self-associates to form a hexameric complex in the presence of AAV ori sequences. J Virol. 1997;71:4461–4471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4461-4471.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Snyder R O, Im D S, Muzyczka N. Evidence for covalent attachment of the adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep protein to the ends of the AAV genome. J Virol. 1990;64:6204–6213. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6204-6213.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Snyder R O, Im D S, Ni T, Xiao X, Samulski R J, Muzyczka N. Features of the adeno-associated virus origin involved in substrate recognition by the viral Rep protein. J Virol. 1993;67:6096–6104. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6096-6104.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Snyder R O, Samulski R J, Muzyczka N. In vitro resolution of covalently joined AAV chromosome ends. Cell. 1990;60:105–113. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90720-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Srivastava A, Lusby E W, Berns K I. Nucleotide sequence and organization of the adeno-associated virus 2 genome. J Virol. 1983;45:555–564. doi: 10.1128/jvi.45.2.555-564.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Straus S E, Sebring E D, Rose J A. Concatemers of alternating plus and minus strands are intermediates in adenovirus-associated virus DNA synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:742–746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.3.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tratschin J D, Miller I L, Carter B J. Genetic analysis of adeno-associated virus: properties of deletion mutants constructed in vitro and evidence for an adeno-associated virus replication function. J Virol. 1984;51:611–619. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.3.611-619.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Urabe M, Hasumi Y, Kume A, Surosky R T, Kurtzman G J, Tobita K, Ozawa K. Charged-to-alanine scanning mutagenesis of the N-terminal half of adeno-associated virus type 2 Rep78 protein. J Virol. 1999;73:2682–2693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2682-2693.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Urcelay E, Ward P, Wiener S M, Safer B, Kotin R M. Asymmetric replication in vitro from a human sequence element is dependent on adeno-associated virus Rep protein. J Virol. 1995;69:2038–2046. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2038-2046.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Venkatesan M, Silver L L, Nossal N G. Bacteriophage T4 gene 41 protein, required for the synthesis of RNA primers, is also a DNA helicase. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:12426–12434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walker S L, Wonderling R S, Owens R A. Mutational analysis of the adeno-associated virus Rep68 protein: identification of critical residues necessary for site-specific endonuclease activity. J Virol. 1997;71:2722–2730. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2722-2730.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walker S L, Wonderling R S, Owens R A. Mutational analysis of the adeno-associated virus type 2 Rep68 protein helicase motifs. J Virol. 1997;71:6996–7004. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6996-7004.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ward P, Urcelay E, Kotin R, Safer B, Berns K I. Adeno-associated virus DNA replication in vitro: activation by a maltose binding protein/Rep 68 fusion protein. J Virol. 1994;68:6029–6037. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6029-6037.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Warrener P, Tamura J K, Collett M S. RNA-stimulated NTPase activity associated with yellow fever virus NS3 protein expressed in bacteria. J Virol. 1993;67:989–996. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.989-996.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weitzman M D, Kyöstiö S R M, Carter B J, Owens R A. Interaction of wild-type and mutant adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep proteins on AAV hairpin DNA. J Virol. 1996;70:2440–2448. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2440-2448.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weitzman M D, Kyöstiö S R M, Kotin R M, Owens R A. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep proteins mediate complex formation between AAV DNA and its integration site in human DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5808–5812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wonderling R S, Kyöstiö S R M, Owens R A. A maltose-binding protein/adeno-associated virus Rep68 fusion protein has DNA-RNA helicase and ATPase activities. J Virol. 1995;69:3542–3548. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3542-3548.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wonderling R S, Kyöstiö S R M, Walker S L, Owens R A. The Rep68 protein of adeno-associated virus type 2 increases RNA levels from the human cytomegalovirus major immediate early promoter. Virology. 1997;236:167–176. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wonderling R S, Owens R A. Binding sites for adeno-associated virus Rep proteins within the human genome. J Virol. 1997;71:2528–2534. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2528-2534.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wonderling R S, Owens R A. The Rep68 protein of adeno-associated virus type 2 stimulates expression of the platelet-derived growth factor B c-sis proto-oncogene. J Virol. 1996;70:4783–4786. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4783-4786.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhou X, Zolotukhin I, Im D S, Muzyczka N. Biochemical characterization of adeno-associated virus Rep68 DNA helicase and ATPase activities. J Virol. 1999;73:1580–1590. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1580-1590.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]