Abstract

In a previous study we showed that multiple deletions of the adenoviral regulatory E1/E3/E4 or E1/E3/E2A genes did not influence the in vivo persistence of the viral genome or affect the antiviral host immune response (Lusky et al., J. Virol. 72:2022–2032, 1998). In this study, the influence of the adenoviral E4 region on the strength and persistence of transgene expression was evaluated by using as a model system the human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) cDNA transcribed from the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. We show that the viral E4 region is indispensable for persistent expression from the CMV promoter in vitro and in vivo, with, however, a tissue-specific modulation of E4 function(s). In the liver, E4 open reading frame 3 (ORF3) was necessary and sufficient to establish and maintain CFTR expression. In addition, the E4 ORF3-dependent activation of transgene expression was enhanced in the presence of either E4 ORF4 or E4 ORF6 and ORF6/7. In the lung, establishment of transgene expression was independent of the E4 gene products but maintenance of stable transgene expression required E4 ORF3 together with either E4 ORF4 or E4 ORF6 and ORF6/7. Nuclear run-on experiments showed that initiation of transcription from the CMV promoter was severely reduced in the absence of E4 functions but could be partially restored in the presence of either ORF3 and ORF4 or ORFs 1 through 4. These results imply a direct involvement of some of the E4-encoded proteins in the transcriptional regulation of heterologous transgenes. We also report that C57BL/6 mice are immunologically weakly responsive to the human CFTR protein. This observation implies that such mice may constitute attractive hosts for the in vivo evaluation of vectors for cystic fibrosis gene therapy.

The ability of replication-deficient adenoviruses (Ad) to efficiently transfer and express candidate therapeutic genes into a variety of dividing and postmitotic cell types (4, 30, 58) makes such viruses very effective vectors for direct in vivo gene therapy protocols (3, 7, 17, 19, 27, 47, 54). However, the success of vectors defective in both E1 and E3 (AdE1°E3°) that are currently used in human gene therapy is compromised by several drawbacks, including the demonstration that transgene expression is in most cases only transient in vivo (2, 18, 21, 35, 39, 57). A series of studies in recent years have investigated the molecular and immunological mechanisms involved in the in vivo control of transgene expression. They have suggested that the strength and persistence of transgene expression can be influenced by multiple factors, such as the immunological background of the selected mouse model (2, 43), the immunogenicity of the transgene product (43, 59, 62), the type of immune response generated in the treated hosts (14), and the genomic structure of the vector backbone (1, 10, 22). Altogether, these studies have established that, provided that the transgene product is nonimmunogenic, recombinant Ad can allow long-term in vivo persistence of transgene expression despite the induction of a detectable antiviral cellular and humoral immune response.

However, these studies also demonstrated that administration of currently available Ad with deletions of E1 and E3 is often associated with high levels of tissue toxicity and inflammation, which may hamper the use of such vectors at high viral doses in human patients (19, 50, 51). To reduce the toxicity, and eventually the immunogenicity, of the recombinant vectors, Ad with several regulatory genes simultaneously deleted have been generated and analyzed for their in vitro and in vivo properties (1, 22, 25, 26, 28, 29, 40, 45, 50, 61, 64). We have shown in a previous study that the simultaneous deletion of the viral E1, E3, and E2A regions (AdE1°E3°E2A°) or of the E1, E3, and E4 regions (AdE1°E3°E4°) did not alter the in vivo persistence of the vector genome or affect the host cellular and humoral antiadenovirus immune responses (40). However, the simultaneous deletion of the E1, E3, and E4 regions did have a significant impact on in vivo liver toxicity and inflammatory responses. Consistent with previous reports (23, 29), we found that hepatotoxicity and inflammation were markedly reduced in the absence of the viral E1 and E4 regions (15). In contrast, induction of liver dystrophy and inflammation did not differ when AdE1°E3° and AdE1°E3°E2A° vectors were compared in different strains of mice. Similar findings have been reported by O’Neal et al. (50). These results imply a direct involvement of viral E4 gene products in the induction of the host inflammatory response.

Unexpectedly, and adding to the complexity of multiple factors influencing Ad-mediated transgene expression, the viral E4 region was recently shown to have a direct influence on the persistence of transgene expression. When the transgene was regulated from the immediate-early cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter or the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) promoter, long-term expression was found to be dependent on the presence of an intact viral E4 region in cis or in trans (1, 10, 22, 31). These studies suggested that the viral E4 gene products can regulate, at the transcriptional and/or posttranscriptional level, the expression of nonviral genes under the control of heterologous regulatory sequences such as the CMV promoter.

To further investigate the role of the individual E4 gene products in the expression of CMV-driven transgenes and to aim at combining high-level and persistent transgene expression with low toxicity and low inflammatory response to the vector, the viral E4 region was dissected. A series of isogenic vectors carrying human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (hCFTR) cDNA under the control of the CMV promoter, and containing individual E4 open reading frames (ORFs) or combinations thereof, was generated. The purpose of this study was to assess the influence of the individual E4 gene products on CMV-driven hCFTR transgene expression in vitro and in vivo in the livers and lungs of immunocompetent and immunodeficient strains of mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viral vectors.

All viral genomes were constructed as infectious plasmids by homologous recombination in Escherichia coli as described by Chartier et al. (13). In brief, all vectors (Table 1) contain a deletion in E1 from nucleotide (nt) 459 to nt 3327 and in E3 (from nt 28592 to nt 30470 or from nt 27871 to nt 30748 [see Table 1]). Nucleotide numbering throughout this paper conforms to that of Chroboczek et al. (16). The E4 regions were modified as described below. The vectors also contain in E1 the hCFTR cDNA (3) transcribed from the human CMV promoter (6) and terminated by the polyadenylation signal from the rabbit β-globin gene.

TABLE 1.

Properties of Ad vectors with modifications of E4

| Virusa | E4 regionb | Promoter for hCFTR expression | Titer (1011 IU/ml) | Titer (1012 P/ml)c | P/IU ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AdTG6418 | wt | CMV | 2 | 5.8 | 29 |

| AdTG5643 | ORF1 | CMV | 1.4 | 3.3 | 23 |

| AdTG6421 | ORF6,7 | CMV | 2.3 | 7.4 | 32 |

| AdTG6447 | ORF1-4 | CMV | 2 | 3.1 | 16 |

| AdTG6449 | ORF3,4 | CMV | 2.2 | 4.9 | 22 |

| AdTG6477 | ORF3 | CMV | 1.34 | 2.5 | 18.6 |

| AdTG6487 | ORF4 | CMV | 1 | 7 | 70 |

| AdTG6490 | ORF3,6,7 | CMV | 3.8 | 7.5 | 20 |

| AdTG6429 | wt | RSV | 2.3 | 3.9 | 17 |

| AdTG5687 | ORF1 | RSV | 1.3 | 3.2 | 26 |

All vectors have deletions in the viral E3 region. In AdTG6421, the deletion in E3 extends from nt 27871 to nt 30748; in all other vectors, the deletion in E3 extends from nt 28592 to nt 30470. All vectors, except AdTG6429 and AdTG5687, contain the CMV-hCFTR expression cassette in place of the E1 region. AdTG6429 and AdTG5687 carry the hCFTR cDNA under the control of the long-terminal-repeat sequences from the RSV.

wt, wild type.

P, viral particles.

E4 modifications.

All vectors use the viral E4 promoter to drive the expression of the wild-type or modified E4 region. The modifications introduced into the E4 region of the vectors with the hCFTR expression cassette are listed in Table 1 and as follows. The AdTG6418 vector (wtE4) contains the wild-type E4 region. The AdTG5643 vector (ORF1) contains a deletion in E4 removing most of the E4 coding sequences (nt 32994 to 34998) except ORF1. This deletion is identical to the H2dl808 deletion previously described for Ad2 (12). The AdTG6447 vector (ORF1-4) retains E4 ORF1, ORF3, ORF4, and ORF3/4 and lacks ORF6 and ORF6/7. The deletion (from nt 32827 to nt 33985) removes the viral sequences between the MunI (nt 32822) and AccI (nt 33984) sites. The AdTG6449 vector (ORF3,4) retains E4 ORF3, ORF4, and ORF3/4. It was derived from AdTG6447 by deletion of the viral sequences from nt 34799 to nt 35503, between the PvuII site (nt 34796) and the Eco47-3 site (nt 35501). The AdTG6477 vector (ORF3) retains E4 ORF3 and was derived from AdTG6449 by a deletion within ORF4 of the sequences from nt 34069 to nt 34190, between the TthI (nt 34064) and NarI (nt 34189) sites. The AdTG6487 vector (ORF4) retains E4 ORF4 and was derived from AdTG6447 by deletion of the sequences from ORF1 through ORF3, between the SspI site (nt 34632) and the Eco47-3 site (nt 35503). The AdTG6421 vector (ORF6,7) retains ORF6 and ORF6/7 and was derived from the AdTG6418 by deletion of the sequences from ORF1 through 4, between the BglII site (nt 34112) and the AvrII site (nt 35461). The AdTG6490 vector (ORF3,6,7) retains ORF3, ORF6, and ORF6/7 and was derived from AdTG6418 by deletion of the sequences from nt 34799 to nt 35503, between the PvuII site (nt 34796) and the Eco47-3 site (nt 35501). E4 ORF4 was then inactivated as described above, by deletion of the sequences from nt 34069 to nt 34190, between the TthI (nt 34064) and NarI (nt 34189) sites. In this construction, E4 ORF6 is not complete: the deletion of the sequences between the TthI and NarI sites also removed the first ATG codon (nt 34074) of the ORF6 sequence. Since this vector could be amplified to high titers in the absence of E4 complementation (see Fig. 5), we conclude that translation of the ORF6 and ORF6/7 genes starting at the second ATG codon (nt 34047), present at amino acid 10 in the translational frame of ORF6, leads to functional ORF6 and ORF6/7 products (see below).

FIG. 5.

Reactivation of CMV-driven transgene expression by E4 gene products. The E1/E3/E4 deletion vector carrying the CMV-hCFTR expression cassette (AdTG5643 [Table 1]) was administered intratracheally to SCID mice at a dose of 1.5 × 109 IU/animal, with five animals per time point. Mice were sacrificed and analyzed at day 3 and day 30 postinjection. At day 45 postinjection, the mice were reinjected intratracheally with an E1/E3/E4 deletion vector with no transgene but retaining E4 ORFs 1 through 4. The presence in the lungs of both vector genomes and of hCFTR mRNA was analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

Virus generation, viral growth, and titration.

For the generation of viruses, the viral genomes were released from the respective recombinant plasmids by PacI digestion and transfected into the appropriate complementation cell lines, as described previously (13, 40). Vectors with a wild-type E4 region were generated in 293 cells, whereas all vectors with modifications of E4 were generated in 293-E4ORF6+7 cells, described previously (40). Virus propagation, purification, and titration of infectious units (IU) by indirect immunofluorescence of the viral DNA binding protein (DBP) were carried out as described previously (40). Purified virus was stored in viral storage buffer (1 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.5], 1 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 0.005% [vol/vol] Tween 80). The viral particle concentration of each vector preparation was calculated by using the optical density for measurement of viral DNA content (44). The particle-to-infectious-unit ratios are given in Table 1. The growth of vectors with modifications of E4 in the presence and absence of E4 complementation was assessed in 293 cells and compared to that in 293-E4ORF6+7 cells.

Animal studies.

Six-week-old female immunocompetent mice (C57BL/6, H-2b; C3H, H-2k; CBA, H-2k) and immunodeficient C.B17-scid/scid mice were purchased from IFFA-CREDO (L’Arbreles, France). The vectors containing the hCFTR transgene were administered intratracheally, diluted in 0.9% NaCl, or intravenously, in viral storage buffer, at the indicated doses. Animals were sacrificed at the times indicated, and organs were removed, cut into equal pieces, and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen until analysis.

DNA analysis.

Total DNA was extracted from tissue culture cells and organs as described previously (40). Briefly, cells or tissues were digested overnight with a proteinase K solution (1 mg of proteinase K in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) in DNA lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 400 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA). Total cellular DNA was isolated by phenol-chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. DNA (10 μg) was digested with BamHI and analyzed by Southern blot analysis using a 32P-labeled EcoRI-HindIII restriction fragment purified from Ad5 genomic DNA (nt 27331 to 31993). The quality and quantities of DNA were monitored by ethidium bromide staining of the gels prior to transfer.

RNA analysis.

For the detection of viral gene and transgene expression, the steady-state levels of the respective mRNAs were monitored by Northern blot analysis. Total RNA was extracted from tissue culture cells and organs by using the RNA Now kit (Ozyme, Saint-Quentin-les-Yvelines, France) as recommended by the supplier. For Northern blot analysis, 10 to 15 μg of total RNA was subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis (52) and transferred to nitrocellulose filters. Filters were stained after transfer to ensure that equal amounts of total cellular RNA were loaded and transferred. hCFTR mRNA was detected by using a 32P-labeled BamHI restriction fragment (2,540 bp) purified from the CFTR cDNA. Viral mRNA was detected by using a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide (OTG10581), specifically hybridizing to the hexon mRNA of the viral L3 messages.

Nuclear run-on transcription assay.

The techniques for preparation of nuclear transcription and analysis of labeled nascent RNA by hybridization to denatured plasmid DNAs immobilized on nitrocellulose filters were essentially as described previously (32). Briefly, confluent monolayers of A549 cells were infected with the indicated vectors at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 IU/cell and incubated for 48 h at 37°C. Nuclei from the infected cells were prepared exactly as described previously (32). In vivo-initiated RNA transcripts from aliquots containing 2 × 107 nuclei were elongated in vitro for 30 min at 30°C in the presence of 100 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (3,000 Ci/mmol) in a final volume of 200 μl containing 1 mg of heparin/ml, 0.6% (vol/vol) Sarkosyl, 0.4 mM (each) ATP, GTP, and CTP, 2.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.15 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 350 mM (NH4)2SO4. The reaction was terminated, and labeled RNA was isolated, exactly as described previously (32). Dried RNA pellets were dissolved to a final specific activity of 3.4 × 106 cpm/ml in hybridization buffer containing 40% formamide, 2 mM EDTA, 0.9 M NaCl, 50 mM Na2HPO4–NaH2PO4 (pH 6.5), 1% SDS, 0.4 g of polyvinylpyrrolidone/liter, 0.4 g of Ficoll/liter, 50 g of dextran sulfate/liter, and 50 mg of denatured salmon sperm DNA/liter. A portion (1.7 × 106 cpm) of each labeled RNA was used to hybridize to immobilized denatured plasmid DNA containing the hCFTR cDNA, the human β-actin cDNA (internal control), and the plasmid backbone (negative control). These plasmid DNAs were linearized, denatured in the presence of 0.3 N NaOH, and immobilized on nitrocellulose filters by using a dot blot apparatus (5 μg of plasmid DNA/dot). Prehybridization at 42°C for 18 h and hybridization at 42°C for 3 days were carried out in the same hybridization buffer (see above). Filters were washed twice in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–1% SDS for 15 min at 22°C and twice in 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS for 15 min at 52°C. Radioactivity bound to the filter was quantified by scintillation counting.

Enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay.

Ninety-six-well nitrocellulose plates (Millipore, Saint Quentin les Yvelines, France) were coated with 0.3 μg of monoclonal rat anti-mouse gamma interferon (IFN-γ) antibody (Pharmingen, Becton Dickinson, Le Pont de Claix, France)/well overnight at 4°C. Wells were washed twice with complete Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) plus 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and were then incubated for 2 h at 37°C with 150 μl of complete DMEM plus 10% FCS. Splenocytes recovered from CBA, C3H, or C57BL/6 mice that had been injected 7 days before sacrifice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or with 109 IU of an E1/E3 deletion Ad expressing or not expressing hCFTR were plated at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/well in a volume of 100 μl. Stimulator L929 or RMA cells infected for 6 h at an MOI of 4 with a vaccinia virus expressing hCFTR were submitted to a 15-min UV-light treatment to inactivate the virus and were then added at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells per well containing CBA/C3H or C57BL/6 splenocytes, respectively. Another stimulation was performed by direct addition of Ad vectors with or without the hCFTR transgene to the splenocytes at an MOI of 20. Interleukin-2 (6 IU) was then added to all the wells. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h and washed five times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20. Wells were then incubated with 0.3 μg of biotinylated monoclonal rat anti-mouse IFN-γ antibody (Pharmingen, Becton Dickinson)/well overnight at 4°C and subsequently were washed five times with PBS-Tween, and 100 μl of a 1/5,000 dilution of Extravidin alkaline phosphatase (Sigma, Ivry-sur-Seine, France) was added for 45 min at room temperature. Wells were washed five times with PBS-Tween, and 100 μl of an alkaline phosphatase (AP) conjugate substrate kit solution (Bio-Rad, Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France) was added for 30 min at room temperature. The substrate solution was discarded, and the plates were washed under running tap water and air dried. Colored spots were counted by using a dissecting microscope.

Data processing.

All autoradiograms were scanned and assembled in Adobe Photoshop.

RESULTS

C57BL/6 mice develop a weak immunological response to the hCFTR protein.

To study the impact of the simultaneous deletions of the viral E1, E3, and E4 regulatory genes on the persistence of transgene expression, isogenic AdE1°E3° (AdTG6418) and AdE1°E3°E4° (AdTG5643) vectors carrying the hCFTR transgene under the control of the CMV promoter were generated (Table 1) and compared in vitro and in vivo. Since the hCFTR protein could be recognized as foreign by the mouse immune system, a first series of experiments using the E1/E3 deletion vector was performed in immunodeficient SCID mice (Fig. 1A) and immunocompetent C3H, C57BL/6, and CBA mice (Fig. 1B and C; also data not shown) to determine the influence of the immune response on the persistence of hCFTR expression. Throughout most of this study, the steady-state level of transgene mRNA, detected by Northern blot analysis, was used to monitor the expression of the transgene.

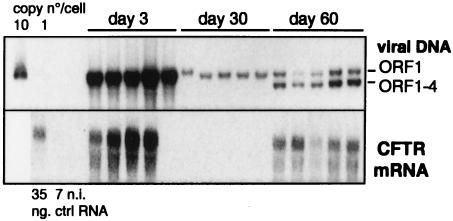

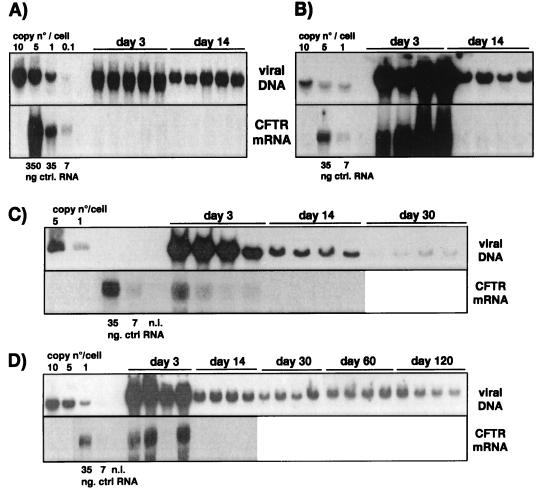

FIG. 1.

Persistence of viral DNA and hCFTR gene expression in the presence of the wild-type E4 region in the lungs of immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice. The E1/E3 deletion vector expressing hCFTR (AdTG6418 [Table 1]) was administered intratracheally to SCID (A), C3H (B), and C57BL/6 (C) mice at a dose of 1.5 × 109 IU/animal, with six animals per time point for the SCID mice and five animals per time point for the C3H and C57BL/6 mice. The animals were sacrificed on the indicated days, and the persistence of the viral DNA in the lungs was analyzed by Southern blotting. Control lanes contain 10, 5, 1, and 0.1 viral genome copies, each mixed with 10 μg of lung cellular DNA from an untreated mouse (1 viral genome copy is equivalent to 30 pg of viral DNA). Expression of hCFTR in the lung was analyzed by Northern blotting using an hCFTR-specific DNA probe. Control lanes contain 35 and 7 ng of total RNA from AdTG6418-infected 293 cells mixed with 10 μg of lung RNA from an untreated mouse. Lung DNA and RNA were extracted and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes marked n.i. contain DNA or RNA from the lungs of noninfected mice.

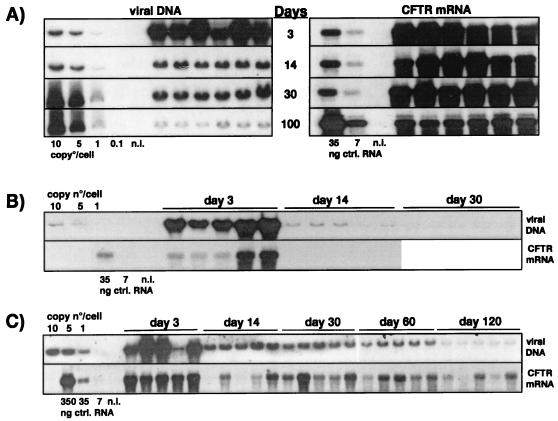

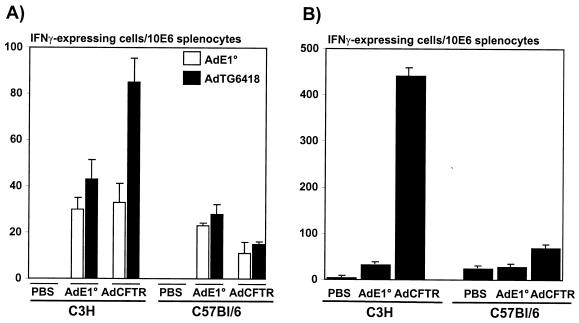

As expected, intratracheal administration of AdTG6418 to immunodeficient SCID mice led to strong and stable CMV-driven hCFTR expression in the lung, maintained over 100 days (the duration of the experiment [Fig. 1A]), and the vector genome remained readily detectable throughout this period (Fig. 1A). In contrast, expression of hCFTR was very transient in immunocompetent C3H mice (Fig. 1B) and CBA mice (data not shown), and the viral genome copy number declined rapidly to undetectable levels in these animals (Fig. 1B and data not shown). Unexpectedly, administration of the hCFTR vector to the lungs of immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice resulted in stable persistence of both the viral genome and hCFTR expression (Fig. 1C). Quantification of the Southern blots by densitometry scanning confirmed the relatively similar persistence of the E1/E3 deletion vector DNA (AdTG6418) in SCID and C57BL/6 mice and the rapid elimination of the viral genome in C3H animals (Fig. 2A). We and others have previously shown that C57BL/6 mice are immunologically tolerant of secreted human proteins such as coagulation factor IX (43, 63, 65) or alpha-1-antitrypsin (2). These observations suggest that C57BL/6 mice may also be tolerant of nonsecreted human proteins such as hCFTR. To investigate this hypothesis, C3H and C57BL/6 mice were injected intravenously with the AdTG6418 vector and their splenocytes were recovered for the determination of the presence of a virus- and/or transgene-specific T-cell response by an ELISPOT assay (20). This analysis showed that similar antiadenoviral responses were induced in C3H and in C57BL/6 mice treated with the E1/E3 deletion vector without any transgene (AdE1°), regardless of whether the splenocytes were then stimulated with the same vector or with the hCFTR-expressing virus (Fig. 3A). However, the number of IFN-γ-producing cells was increased in C3H mice, but not in C57BL/6 mice, when they were injected with the hCFTR-expressing vector (AdTG6418 [Table 1]) and their splenocytes were stimulated with AdTG6418 (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the anti-hCFTR response might be stronger in C3H mice than in C57BL/6 mice. This observation was confirmed by an experiment in which the mouse splenocytes were stimulated with syngeneic L929 or RMA cells infected with a vaccinia virus expressing hCFTR (Fig. 3B). Only C3H mice were found to develop a strong cellular immune response against hCFTR (Fig. 3B), confirming that C57BL/6 mice are immunologically less responsive to hCFTR.

FIG. 2.

Quantification of the persistence of the viral DNA in the presence or absence of the E4 region in the lungs of immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice. Autoradiograms corresponding to the Southern blots shown in Fig. 1 and in Fig. 4C and D were quantified by densitometry scanning, and the values are reported in panels A and B, respectively. (A) Persistence of the viral DNA in SCID (⧫), C57BL/6 ( ), and C3H (●) mice injected intratracheally with the E1/E3 deletion vector expressing hCFTR (AdTG6418 [Table 1]). (B) Persistence of the viral DNA in C57BL/6 (

), and C3H (●) mice injected intratracheally with the E1/E3 deletion vector expressing hCFTR (AdTG6418 [Table 1]). (B) Persistence of the viral DNA in C57BL/6 ( ) and C3H (●) mice injected intratracheally with the E1/E3/E4 deletion vector expressing hCFTR (AdTG5643 [Table 1]).

) and C3H (●) mice injected intratracheally with the E1/E3/E4 deletion vector expressing hCFTR (AdTG5643 [Table 1]).

FIG. 3.

Induction of anti-adenovirus and anti-hCFTR cellular responses in C3H and in C57BL/6 mice. Splenocytes were recovered from C3H and C57BL/6 mice injected intravenously 7 days earlier with PBS, with an E1/E3 deletion vector expressing hCFTR (AdTG6418 [Table 1]), or with an E1/E3 deletion vector carrying no transgene (AdE1°). The splenocytes were then analyzed by an ELISPOT assay for the presence of IFN-γ-expressing cells after stimulation with either AdE1° (open bars) or Ad-hCFTR (solid bars) (A) or after stimulation with syngeneic RMA cells (for C57BL/6 splenocytes) or L929 cells (for C3H splenocytes) infected with a vaccinia virus expressing hCFTR (B).

We conclude that a comparative in vivo evaluation of AdE1°E3°-hCFTR (AdTG6418) and AdE1°E3°E4°-hCFTR (AdTG5643) vectors in C57BL/6 and SCID mice should allow a better determination of the influence of the viral genomic structure on the persistence of transgene expression in both immunocompetent and immunodeficient hosts, without major interference by the anti-hCFTR immune response.

E4-mediated regulation of CMV-driven hCFTR expression in vivo.

The AdE1°E3°E4°-hCFTR vector (AdTG5643 [Table 1]) was administered intratracheally and intravenously to SCID mice to determine the in vivo effect of E4 on the level and persistence of hCFTR expression. Consistent with previous results (1, 10), the comparative analysis of hCFTR expression in the livers (Fig. 4A) and lungs (Fig. 4B) of SCID mice showed that transgene expression was not persistent in the absence of the viral E4 region. Moreover, a tissue-specific modulation of the E4 effect was apparent: in the absence of E4 sequences, no expression from the CMV promoter was detectable in the liver at any time (Fig. 4A), while transgene expression in the lung, although strong early after virus administration, declined to undetectable levels by 2 weeks postadministration (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that viral E4 functions are absolutely required for the establishment and maintenance of CMV-driven transgene expression in the liver, whereas in the lung, viral E4 functions are not required for the initial activation of transgene expression but are required for its persistence. Thus, the viral E4 proteins, together with uncharacterized tissue-specific factors, appear to control the strength and stability of transgene expression.

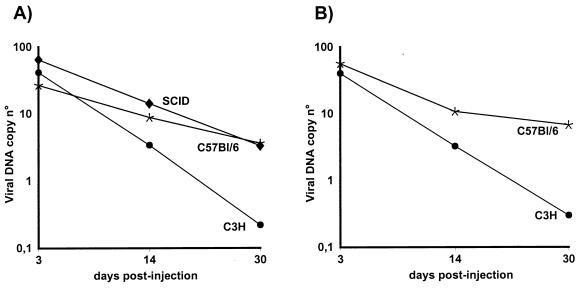

FIG. 4.

Shutoff of CFTR expression in the absence of the viral E4 region. The E1/E3/E4 deletion vector carrying the CMV-hCFTR expression cassette (AdTG5643 [Table 1]) was administered intravenously to SCID mice (A) and intratracheally to SCID (B), C3H (C), and C57BL/6 (D) mice, at a dose of 1.5 × 109 IU/animal, with five (A) or four (B through D) animals per time point. The animals were then sacrificed on the indicated days, and the persistence of viral DNA and expression of hCFTR in the lungs and liver were analyzed by Southern and Northern blotting, as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

A similar influence of E4 on transgene expression was observed in immunocompetent C57BL/6 and C3H mice injected intratracheally with the AdE1°E3°E4°-hCFTR vector: in the absence of E4, hCFTR was expressed in the lung at day 3 postinoculation but was undetectable at day 14 in both strains of animals (Fig. 4C and D). Quantification of the Southern blots revealed again the more-rapid decline of the viral DNA copy number in C3H mice (Fig. 2B), probably as a consequence of the induction of an anti-hCFTR immune response in these animals (Fig. 3).

Interestingly, expression from the CMV promoter is not irreversibly silenced in vivo (Fig. 5): SCID mice which were initially injected intratracheally with the AdE1°E3°E4°-hCFTR vector and in which CMV-driven transgene expression had disappeared by day 30 were reinjected by the same route at day 45 with a CFTR-less AdE1°E3° vector containing E4 ORFs 1 through 4. Viral DNA and hCFTR mRNA were analyzed at day 60 (15 days after administration). Figure 5 shows that readministration of the vector retaining E4 ORFs 1 through 4 resulted in the coexistence of both viral genomes, without any significant change in the levels of AdE1°E4°-hCFTR vector DNA. However, this administration of the vector containing E4 ORFs 1 through 4 led to a reactivation of hCFTR expression by day 60. These results confirm and extend those of Brough et al. (10) and, taken together, suggest that E4 products encoded by ORFs 1 through 4 can in trans regulate the expression of the CMV promoter in vivo. Moreover, these data suggest an involvement of the E4 functions at the transcriptional level (see below).

Influence of the individual E4 ORFs on viral growth in vitro.

The reinfection experiment described above indicated that E4 sequences containing ORF1, ORF2, ORF3, ORF4, and ORF3/4 are sufficient to complement in trans the deficiency of CMV-driven transgene expression from an AdE1°E3°E4-hCFTR vector. This observation led us to investigate whether the E4-encoded trans-acting functions could be ascribed to defined E4 gene products.

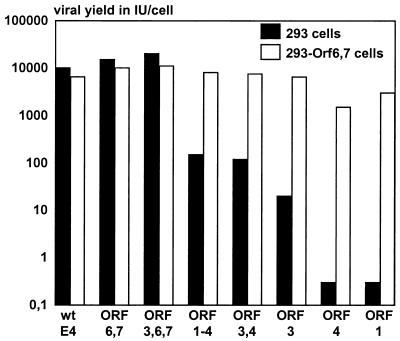

Therefore, a series of isogenic E1/E3/E4 modification vectors carrying the CMV-hCFTR transgene and containing individual E4 ORFs or combinations of E4 ORFs was generated by homologous recombination in E. coli as previously described (13) (Table 1). As shown in Fig. 6, all vectors could be purified to high titers in 293 cells expressing the E4 ORF6 and ORF6/7 genes (38), with virus particle/infectious unit ratios below 50. The only exception was the vector containing only E4 ORF4, which reproducibly gave lower viral yields and a virus particle/infectious unit ratio greater than 50:1 (Table 1; Fig. 6). The reduced viral yields of the AdE1°E4°ORF4 vectors in 293-E4ORF6,7 cells are consistent with the findings of a previous study showing strong inhibition of viral DNA replication with vectors containing ORF4 only (9). In addition, the ORF4 gene product has recently been reported to induce apoptosis in a variety of cell types (37, 42, 56), further supporting the negative impact of this protein on viral growth.

FIG. 6.

Growth properties of the E4 modification vectors in 293 cells and in 293-E4ORF6,7 cells. Cells were infected at an MOI of 2 IU/cell with E1/E3 deletion vectors either retaining the wild-type (wt) E4 sequences or having specific modifications in the E4 region. At 48 h postinfection, the viral yields were determined by indirect DBP immunofluorescence (see Materials and Methods) on 293-E4ORF6,7 cells.

In 293 cells, only the vectors retaining ORF6 and ORF6/7, with or without the addition of ORF3 (AdTG6421 and AdTG6490 [Table 1]), could be produced to high titers (Fig. 6). The vectors containing ORFs 1 through 4 (AdTG6447) or ORF3, ORF4, and ORF3/4 (AdTG6449) could also replicate in the absence of E4 complementation, albeit at reduced levels (100-fold reduced compared to the vector with wild-type E4 sequences). Growth of the vector retaining ORF3 only (AdTG6477) was apparent in 293 cells, although the viral yields were reduced approximately 1,000-fold. The vectors containing only ORF4 (AdTG6487) or ORF1 (AdTG5643) could not propagate in 293 cells, as previously reported (33, 40).

It should be pointed out that the entire E4 ORF6 sequence is included in the ORF6,7 vector (AdTG6421 [Table 1]). In contrast, in the construction of the ORF3,6,7 vector (AdTG6490 [Table 1]), the first ATG codon of ORF6 and ORF6/7 has been deleted. Thus, translation of ORF6 and ORF6/7 must utilize the second ATG codon (amino acid 10) in the ORF6 translational frame. Since this vector (AdTG6490) could be produced at high titers on 293 cells (Fig. 6), the first 9 N-terminal amino acids of the ORF6 and ORF6/7 gene products are probably dispensable, at least for viral growth.

Influence of the E4 functions on late viral and transgene expression in vitro.

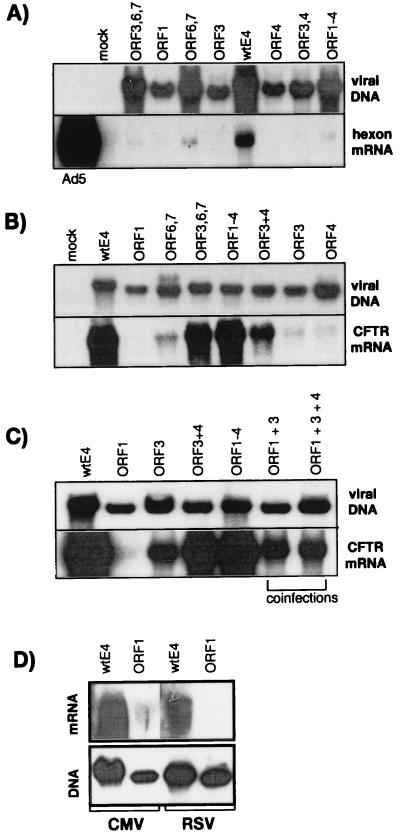

We had previously shown that the simultaneous deletion of the viral E1, E3, and E4 regions resulted in a marked reduction of early and late viral gene expression (40). Therefore, it was of interest to monitor the impact of the individual E4 functions on late viral gene expression. For this, noncomplementing human A549 cells were infected with the indicated vectors at a high MOI (1,000 IU/cell) and the steady-state level of mRNA encoding a representative late viral gene (hexon) was monitored by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 7A). Confirming our previous results, the AdE1°E3° vector did express significant levels of hexon mRNA, although these levels were reduced compared to the amount expressed in cells infected with wild-type Ad5. All other vectors showed reduced hexon mRNA expression. The two vectors retaining ORF6 and ORF6/7 (AdTG6421 and AdTG6490 [Table 1]) were also characterized by reduced late viral gene expression (Fig. 7A, lower panel) despite a substantial amount of viral DNA synthesis (Fig. 7A, upper panel). These results confirm that, in the absence of E1 proteins, deletion of E4 ORFs impairs adenoviral gene expression, even when cells are infected at elevated MOIs. As previously reported (40), late viral gene expression could not be detected at lower MOIs, and therefore differences could not be scored.

FIG. 7.

Expression of transgene and late viral genes in cells infected with E4 modification vectors. Human A549 cells were infected with the indicated E4 modification vectors at MOIs of 1,000 IU/cell (A) and 100 IU/cell (B and D). In panel C, the single infections were performed at an MOI of 200 IU/cell, while the double and triple infections were performed at an MOI of 100 IU/cell for each vector. Wild-type (wt) Ad5 was used at an MOI of 0.5 IU/cell. Total DNA and RNA were then extracted at 72 h postinfection and processed as described in the legend to Fig. 2 and in Materials and Methods. L3 hexon mRNA was detected with a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide.

Transgene expression from the CMV promoter was efficient in the absence of E1 proteins when specific combinations of functional E4 ORFs were maintained in the AdE1°E3°E4° vector (Fig. 7B). Infection of A549 cells with the indicated vectors at an MOI of 100 IU/cell (which does not allow replication of the viral DNA [Fig. 7B, upper panel]) resulted in efficient expression from the CMV promoter (Fig. 7B, lower panel) for vectors retaining ORFs 1 through 4 (AdTG6447) or ORF3, ORF6, and ORF6/7 (AdTG6490). Weak transgene expression was obtained with the vectors containing ORF3 (AdTG6477) or ORF4 (AdTG6487) alone. However, transgene expression was significantly enhanced with the vector retaining both ORF3 and ORF4 (AdTG6449). The vector containing ORF6 and ORF6/7 (AdTG6421) led to low levels of transgene expression, but addition of ORF3 (AdTG6490) could enhance transgene expression to normal levels. In summary, ORF3 together with either ORF4 or ORF6 and ORF6/7 could directly or indirectly activate the CMV promoter in vitro to levels observed with the vectors containing the wild-type E4 region.

The stronger activation of transgene expression in the presence of ORFs 1 through 4 compared to the activation observed in the presence of ORF3 alone led us to investigate whether ORF1 could further influence the activation of the CMV promoter. A549 cells were coinfected either with the AdE1°E4°ORF1 vector (AdTG5643) and the vector retaining ORF3 alone (AdTG6477) or with AdTG6477 and the vector retaining ORF4 alone (AdTG6487) (Fig. 7C). Such coinfection, however, did not lead to any significant enhancement of hCFTR expression over that seen with the vector retaining ORF3 alone, suggesting a possible influence of ORF2 or of the ORF3/4 splicing product. Additional viral mutants are thus needed to further address the role of E4 ORF2 and the E4 ORF3/4 splicing product in the regulation of transgene expression. The influence of variable levels of expression of ORF3 in the different vectors can, however, be excluded, since Western blot analyses have shown that ORF3 was similarly expressed in the wild-type E4, E4 ORF3, E4 ORF3,4, E4 ORF1-4, and E4 ORF3,6,7 vectors (data not shown).

We also investigated whether the effect of the viral E4 region was specific to the CMV promoter or could also be observed with other promoters. Figure 7D shows a comparison in A549 cells of vectors carrying hCFTR cDNA under the control of either the CMV promoter (AdTG6418 and AdTG5643 [Table 1]) or the RSV promoter (AdTG6429 and AdTG5687 [Table 1]), both in the presence and in the absence of the viral E4 region. As described above for the CMV promoter, transgene expression from the RSV promoter was not detectable in the absence of the viral E4 region (Fig. 7D) (31). Whether RSV promoter-dependent expression is similarly dependent on E4 ORF3 remains to be determined. It will also be of interest to investigate the effect of the viral E4 region on other promoters, such as cellular promoters.

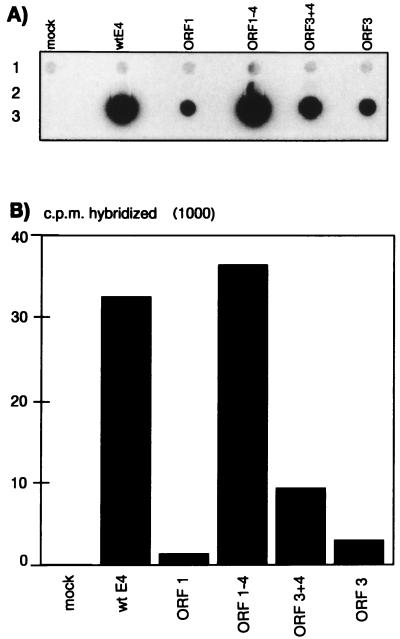

Influence of E4 functions on the rate of initiation of transcription from the CMV promoter.

The effect of E4 on CMV-driven gene expression could be due in part to direct or indirect involvement of the E4 gene products in the initiation of transcription of the transgene. To address this hypothesis, nuclear run-on assays were performed in vitro to monitor the rate of initiation of transcription at the CMV promoter (Fig. 8). Nuclei were isolated from A549 cells infected with the indicated vectors and were incubated in vitro to allow previously initiated RNA polymerases to elongate nascent transcripts. RNA was isolated and hybridized to denatured DNA sequences containing human β-actin cDNA (Fig. 8A, panel 1) as an internal cellular gene control, the plasmid backbone (Fig. 8A, panel 2) as a negative control, and hCFTR cDNA (Fig. 8A, panel 3). The counts bound to each probe were quantified by scintillation counting (Fig. 8B). This analysis shows that the initiation of transcription of the hCFTR transgene was severely reduced (30-fold) in the vector retaining E4 ORF1 only compared to that in the wild-type E4 vector. The presence of ORF3 alone enhanced the initiation of transcription 2- to 3-fold, whereas the presence of E4 ORF3, ORF4, and ORF3/4 or of ORFs 1 through 4 enhanced the initiation of hCFTR transcription 7- and 35-fold, respectively, over that seen with the E4 ORF1 vector. These results clearly indicate that the differences in steady-state mRNA levels (Fig. 7B and C) reflect different transcription rates. We conclude that E4-dependent transcriptional activation of the CMV promoter constitutes part of the mechanism by which E4 functions lead to an enhancement of transgene expression, at least in vitro.

FIG. 8.

Transcription of the transgene in the nuclei of A549 cells infected with E4-modification vectors. A549 cells were infected with the indicated vectors at an MOI of 100 IU/cell for 48 h, and nuclei were then isolated and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Denatured target DNAs were dotted on a filter and hybridized to radiolabeled RNA isolated from the nuclei of the infected A549 cells. The target DNAs are human β-actin cDNA (panel 1), the ppolyII plasmid backbone (panel 2), and hCFTR cDNA (panel 3). wt, wild type. (B) Quantification by scintillation counting of the labeled nuclear RNA hybridized to the hCFTR probe dotted on the filter shown in panel A.

Influence of E4 functions on the strength and persistence of transgene expression in vivo.

To monitor the in vivo effect of the E4 modifications on the level and persistence of CMV-driven transgene expression, the hCFTR vectors were administered by intravenous and intratracheal injections to SCID mice. The persistence of the viral genomic DNA and transgene expression in the lung and liver were monitored over time by Southern and Northern blot analysis (Fig. 9 and 10).

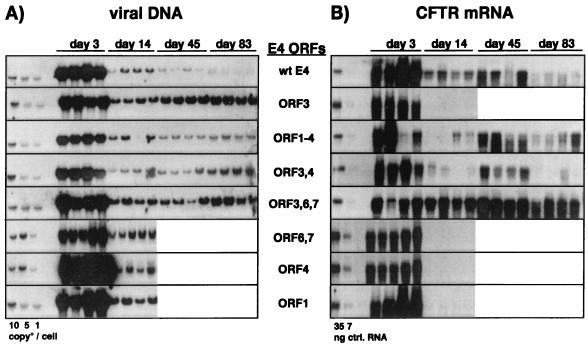

FIG. 9.

E4 ORF3 is required but not sufficient for the persistence of CMV-CFTR expression in the lungs of SCID mice. Vectors with wild-type (wt) E4 sequences or with specific modifications in the E4 region were administered by intratracheal injection to SCID mice at a dose of 1.5 × 109 IU/animal, with four animals per time point. Animals were sacrificed on the indicated days. The persistence of viral DNA (A) and of hCFTR expression (B) in the lung were determined by Southern and Northern blot analysis, respectively. DNA and RNA were extracted and processed as described in the legend to Fig. 1 and in Materials and Methods.

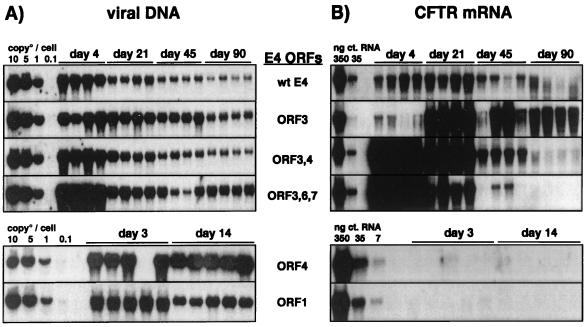

FIG. 10.

E4 ORF3 is sufficient for the persistence of CMV-CFTR expression in the livers of SCID mice. Vectors with wild-type (wt) E4 sequences or with specific modifications in the E4 region were administered by intravenous injection to SCID mice at a dose of 1.5 × 109 IU/animal, with five animals per time point. Animals were sacrificed on the indicated days. The persistence of viral DNA (A) and of hCFTR expression (B) in the liver were determined by Southern and Northern blot analysis, respectively. DNA and RNA were extracted and processed as described in the legend to Fig. 1 and in Materials and Methods.

In the lung, the DNA profiles of all vectors were similar over time (Fig. 9A), indicating that modifications in the vector genome did not significantly affect the persistence of viral genomes in vivo, as shown previously (40). Initially, all vectors expressed the transgene at comparable high levels (Fig. 9B). However, as observed with the AdE1°E4° vector (Fig. 4), hCFTR expression was completely shut off between day 3 and day 14 after injection with the vectors containing ORF3 alone (AdTG6477), ORF4 alone (AdTG6487), or ORF6 and ORF6/7 (AdTG6421). In contrast, transgene expression persisted, although at different levels, with the vectors containing ORFs 1 through 4 (AdTG6449), ORF3, ORF4, and ORF3/4 (AdTG6447), or ORF3, ORF6, and ORF6/7 (AdTG6490). Interestingly, the presence of ORF3 together with ORF6 and ORF7 (AdTG6490) led to constitutive expression at levels higher than those in the presence of both ORF3 and ORF4 (AdTG6447) or in the presence of the wild-type E4 region (AdTG6418). CMV-driven expression from the vectors retaining ORFs 1 through 4 (AdTG6449) or ORF3, ORF4, and ORF3/4 (AdTG6447) appeared reduced at day 14 postinjection, followed by an induction at day 45 and a decline again at day 83. This was not due to differential recovery of RNA, since staining of the nitrocellulose filters after RNA transfer revealed that equivalent amounts of total mRNA were loaded and transferred (data not shown). These results indicate that in the lung, the initial establishment of transgene expression from the CMV promoter is independent of any viral E4 function. However, maintaining strong and persistent transgene expression absolutely requires E4 ORF3 in conjunction with either ORF4 or ORF6 and ORF6/7.

In the liver, the persistence of transgene expression was also dependent on E4 ORF3 function (Fig. 10; also data not shown). However, in comparison to the pattern of transgene expression in the lung, two major differences were noticed. First, the initial activation of the CMV promoter in the liver was absolutely dependent on the ORF3 gene product. No transgene expression was observed at day 3 after administration of vectors lacking ORF3 (Fig. 10; also data not shown). Second, E4 ORF3 alone was sufficient for persistent expression from the CMV promoter; sustained expression of hCFTR did not require the cooperation of ORF3 with either ORF4 or ORF6 and ORF6/7. However, the activation of E3-dependent transgene expression was delayed with the AdE1°E3°E4°ORF3-hCFTR vector. This delay in the appearance of CFTR mRNA could be overcome in the presence of either ORF4 or ORF6 and ORF6/7 in addition to ORF3. The fact that E4 ORF3 was sufficient for long-term transgene expression was confirmed with different transgenes (41).

Together, our results support the notion that the status of the viral E4 region influences the strength and persistence of transgene expression (1, 10), with ORF3 playing a pivotal role in this genetic regulation. While ORF3 is sufficient in the liver, additional viral factors, such as E4 ORF4 or ORF6 and ORF6/7 and/or tissue-specific factors, appear to be required for stable transgene expression in the lung. Furthermore, the E4-dependent enhancement of gene expression is at least in part due to activation of the CMV promoter at the level of the initiation of transcription.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have evaluated the influence of the adenoviral E4 region on the strength and persistence of transgene expression from the CMV promoter in vitro and in vivo. Using a series of isogenic E1/E3 deletion vectors with specific modifications in the E4 region, we confirm and extend earlier observations (1, 10) that the viral E4 region can regulate in cis and in trans the strength and stability of transgene expression from the CMV promoter, and we show that the E4 ORF3 function plays a pivotal role in this genetic regulation. In addition, the biological activity of E4 ORF3 was found to be modulated, as additional viral E4 functions, such as ORF4 or ORF6 and ORF6/7 and/or tissue-specific cellular factors, are required to sustain transgene expression in vivo.

This study used vectors carrying the hCFTR gene under the control of the CMV promoter as a model system. Given the human origin of the transgene, the in vivo evaluation of the vectors was performed in parallel in immunodeficient SCID mice and immunocompetent C3H and C57BL/6 mice in order to determine the influence of the host immunological response against hCFTR on the persistence of transgene expression. In the presence of the wild-type E4 region, extended transgene persistence could be observed in SCID and C57BL/6 mice but not in C3H or CBA mice. This stable expression of the transgene in C57BL/6 mice was correlated with a relatively stable persistence of the viral genome in the transduced cells and with an absence of a detectable anti-hCFTR cellular immune response. In contrast, the viral DNA copy number, and hence hCFTR expression, rapidly declined to undetectable levels in CBA and C3H mice, in correlation with the induction of a cellular anti-hCFTR immune response. Since all immunocompetent mice developed similar antiviral immune responses, these data support our previous results indicating that the host immune response directed against the transgene product plays a predominant role in controlling the in vivo persistence of the transduced cells (14, 40, 43). These results also indicate that C57BL/6 mice may constitute attractive hosts for the in vivo evaluation of vectors for cystic fibrosis gene therapy, since they seem to be fully immunologically responsive to the adenoviral antigens but less responsive to the hCFTR protein. This observation is consistent with previous reports showing extended expression of transgenes encoding secreted human proteins (2, 43, 45, 57, 59), correlated with an impaired antibody response against the secreted human proteins, in C57BL/6 mice but not in other strains of mice. In contrast, Scaria et al. (53) recently described extended CMV-hCFTR expression in the lungs of immunocompetent mice, including C3H and BALB/c mice. These authors suggested that under the conditions described, the hCFTR protein was virtually nonimmunogenic, and they correlated the extended transgene expression with a lack of an anti-hCFTR immune response. Whether the differences in vector backbones contribute to the differing results observed remains to be clarified.

In contrast to the stable transgene expression obtained with the E1/E3 deletion vector containing the wild-type E4 region, CMV-driven transgene expression was shut off with the E1/E3/E4 deletion vector regardless of the immune status of the animals. However, the patterns of transgene expression in the liver and the lung differed from each other. No hCFTR mRNA could be detected at any time in the livers of mice treated intravenously with the E1/E4 deletion vector, while strong hCFTR expression was observed at day 3 postinjection in the lungs of mice treated intratracheally with the same vector. In the latter case, however, transgene expression was unstable and declined to undetectable levels 2 weeks later. Interestingly, the E1/E3/E4 deletion vector was reproducibly less toxic and inflammatory in the livers of immunocompetent mice than the AdE1° vector (15). Together, these results suggest direct involvement of the E4 gene products in gene expression and vector toxicity.

To further investigate the mechanism(s) of E4-mediated regulation of gene expression from the CMV promoter, a series of isogenic CMV-hCFTR expression vectors differing only in the E4 region, and containing individual E4 ORFs or combinations of E4 ORFs, was generated. These vectors were tested for transgene expression in vitro and in SCID mice in the absence of a specific host immune response. The major finding from this study is that the E4 ORF3 gene product is absolutely required for long-term transgene expression from the CMV promoter. However, depending on the target tissue, transgene expression is regulated either by ORF3 alone or by ORF3 together with specific additional E4 gene products. Thus, in the liver, ORF3 was required and sufficient for both the establishment and the long-term maintenance of transgene expression. However, the establishment of strong initial CMV-driven hCFTR expression in the liver was delayed by a few days compared to that with the vector carrying the wild-type E4 region. In the lung, no E4 gene product was required for the establishment of transgene expression, but ORF3 was necessary, although not sufficient, for the long-term maintenance of transgene expression. Sustained transgene expression in the lung required the cooperation of ORF3 with either ORF4 or ORF6 and ORF6/7.

The phenotypic description of E4 functions has evolved through the genetic and molecular analysis of viral mutants with modifications only in E4, and little is known about the influence of E4 gene products on the regulation of heterologous transcription units. The viral E4 region encodes several regulatory functions which seem to act in a pleiotropic fashion in transcription, accumulation, splicing, and transport of early and late mRNAs, in DNA replication, and in virus assembly (reviewed in references 38 and 55). For example, it was shown that the E4 ORF3 and ORF6 proteins increase the production of the viral late proteins by facilitating the cytoplasmic accumulation of the relevant mRNAs at a posttranscriptional level (38, 55). The redundant functions of ORF3 and ORF6 in nuclear RNA stabilization may be linked directly to RNA splicing. Both proteins have been shown to affect viral RNA splicing patterns (48, 49). ORF3 promotes exon inclusion in both viral major late-gene-derived transcripts and nonviral transcripts, while ORF6 promotes exon exclusion. Both ORF3 and ORF6 also play redundant roles in viral DNA replication. However, the ORF3 function is dispensable, whereas the ORF6 function is absolutely required for viral growth, at least in vitro (8, 9, 33). Given the complex effects of the ORF3 and ORF6 proteins on viral gene expression and viral replication, a better characterization of the interactions of these proteins with the host cell components is critical for understanding the influence of these proteins on heterologous gene expression. In this context, it has recently been shown that ORF3 alone, even in the absence of viral infection, can directly affect the distribution of a group of essential transcription/replication factors in the nucleus (11, 23, 24).

Whether this function of ORF3 is related to the requirement for the ORF3 protein for establishment and maintenance of transgene expression, reported here, is currently unclear. However, the results from our in vitro nuclear run-on assays unequivocally demonstrate that the mechanism(s) underlying the regulation of transgene expression from the CMV promoter in the presence of either ORF3 alone, ORF3, ORF4, and ORF3/4, or ORF3, ORF6, and ORF6/7 includes transcriptional activation of the CMV promoter by the E4 functions. These results are entirely consistent with the observation that administration of a vector without a transgene but retaining the E4 functions to animals previously injected with an E1/E3/E4 deletion vector carrying a CMV-driven expression cassette results in reactivation in trans of the CMV promoter in the E1/E3/E4 deletion vector (see Results) (10).

Our studies also show that E4 ORF3 must cooperate either with ORF4 or with ORF6 and ORF6/7 to maintain persistent transgene expression in the lung, while ORF3 is sufficient for stable CMV-driven transgene expression in the liver, despite a delay in the kinetics of hCFTR expression. It has been reported that ORF4 regulates protein phosphorylation in infected cells by binding to the cellular protein phosphatase 2A (36, 46). This interaction results in the selective hypophosphorylation of several cellular and viral proteins, including E1A and the c-Fos component of the AP1 transcription factor. It is not clear whether this function of ORF4 is important, together with ORF3, for the persistence of heterologous transgene expression in the lung. Alternatively, regulation of transgene expression in the presence of ORF3 and ORF4 could also be due to an ORF3/4 function. Such a putative ORF3/4 protein is predicted to exist based on analysis of the viral mRNA generated in Ad2-infected HeLa cells (60), but its existence has not yet been experimentally demonstrated. The molecular mechanisms of regulation of transgene expression by ORF3 together with ORF6 and ORF6/7 also remain unclear. The ORF6/7 product has been shown to bind to the E2F cellular transcription factor and to modulate its activity (34). While there are no apparent E2F binding sites in the CMV promoter, the ORF6/7 or ORF6 product, in concert with the ORF3 protein, could recruit critical cellular transcription factors to modulate CMV promoter activity. Interestingly, several additional, as yet unidentified, cellular proteins have recently been shown to interact with the E4 ORF6 and ORF6/7 proteins (5).

Despite the poor characterization of the mechanisms by which the viral E4-encoded proteins regulate the activity of heterologous promoter sequences, this study clearly shows that the presence of E4 ORF3 is necessary and, at least in the liver, sufficient for stable in vivo transgene expression. This implies that the ORF3 protein can act alone or can cooperate with either ORF4 or ORF6 and ORF6/7, and with specific cellular factors, to control the expression of candidate therapeutic genes. Moreover, our studies demonstrate that the E4 products are involved in regulation of the CMV promoter at the transcriptional level. Further studies are required to more precisely investigate the mechanisms of the E4-dependent activation of transcription and to determine whether other heterologous promoters are similarly regulated by the E4-encoded proteins. This hypothesis is supported by our observation that gene expression from the RSV promoter was also modulated by the E4 region. Whether cellular promoters are also sensitive to E4 is currently under investigation.

Altogether, these studies reemphasize the notion that the architecture of the vector backbone and the choice of the transgene transcription unit constitute important parameters dictating the persistence of transgene expression. Interestingly, the viral E4 region appears to be directly involved in the hepatotoxicity and inflammation profile of the vector as well. Deletion of the E4 region, in addition to E1, markedly decreased the toxicity of the vector and the host inflammation response. Low liver toxicity was also observed for AdE1°E4° vectors retaining either ORF3 alone or ORF3, ORF4, and ORF3/4. In contrast, vectors retaining ORF6 and ORF6/7, with or without ORF3, or ORF4 alone displayed high liver toxicity (15). Thus, E1/E3/E4 deletion vectors retaining a functional E4 ORF3 or a combination of ORF3 and ORF4 combine the desirable feature of long-term transgene expression with low toxicity and low inflammatory responses. Such vectors might be useful for further liver- or lung-directed gene therapy applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to R. Rooke and M. Courtney for their critical comments and suggestions on the manuscript. We thank K. Schughart for the coordination of the animal studies.

This work was supported in part by the Association Française contre la Mucoviscidose (AFLM) and the Association Française contre les Myopathies.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

While the article was under review, we noted that transgene expression in the liver was very weak in the absence of E1 and E4 as early as 6 h postinfection and declined to undetectable levels by 3 days postinfection. In contrast, expression in the presence of E4 was strong and stable during these early time points.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armentano D, Zabner J, Sacks C, Sookdeo C C, Smith M P, St. George J A, Wadsworth S C, Smith A E, Gregory R J. Effect of the E4 region on the persistence of transgene expression from adenovirus vectors. J Virol. 1997;71:2408–2416. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2408-2416.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr D, Tubb J, Fergusson D, Scaria A, Lieber A, Wilson C, Perkins J, Kay M A. Strain related variations in adenovirally mediated transgene expression from mouse hepatocytes in vivo: comparisons between immunocompetent and immunodeficient inbred strains. Gene Ther. 1995;2:151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellon G, Michel-Calemard L, Thouvenot D, Jagneaux V, Poitevin F, Malcus C, Accart N, Layani M P, Aymard M, Bernon H, Bienvenu J, Courtney M, Döring G, Gilly B, Gilly R, Lamy D, Levrey H, Morel Y, Paulin C, Perraud F, Rodillon L, Sené C, So S, Touraine-Moulin F, Schatz C, Pavirani A. Aerosol administration of a recombinant adenovirus expressing CFTR to cystic fibrosis patients: a phase I clinical trial. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:15–25. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkner K L. Development of adenovirus vectors for the expression of heterologous genes. BioTechniques. 1988;6:616–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boivin D, Morrison M R, Marcellus R C, Querido E, Branton P E. Analysis of synthesis, stability, phosphorylation, and interacting polypeptides of the 34-kilodalton product of open reading frame 6 of the early region 4 protein of human adenovirus type 5. J Virol. 1999;73:1245–1253. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1245-1253.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boshart M, Weber F, Jahn G, Dorsch-Hasler K, Fleckenstein B, Schaffner W. A very strong enhancer is located upstream of an immediate early gene of human cytomegalovirus. Cell. 1985;41:521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowles N E, Wang Q. Prospect for adenovirus-mediated gene therapy of inherited diseases of the myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;35:422–430. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bridge E, Ketner G. Redundant control of adenovirus late gene expression by early region 4. J Virol. 1989;63:631–638. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.2.631-638.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bridge E, Medghalchi S, Ubol S, Leesong M, Ketner G. Adenovirus early region 4 and viral DNA synthesis. Virology. 1993;193:794–801. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brough D E, Hsu C, Kulesa V A, Lee G M, Cantolupo L J, Lizonova A, Kovesdi I. Activation of transgene expression by early region 4 is responsible for a high level of persistent transgene expression from adenovirus vectors in vivo. J Virol. 1997;71:9206–9213. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9206-9213.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carvalho T, Seeler J-S, Ohman K, Jordan P, Pettersson U, Akusjarvi G, Carmo-Fonseca M, Dejean A. Targeting of adenovirus E1A and E4-ORF3 proteins to nuclear matrix-associated PML bodies. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:45–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Challberg S S, Ketner G. Deletion mutants of adenovirus 2: isolation and initial characterization of virus carrying mutations near the right end of the viral genome. Virology. 1981;114:196–209. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chartier C, Degryse E, Gantzer M, Dieterlé A, Pavirani A, Mehtali M. Efficient generation of recombinant adenovirus vectors by homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. J Virol. 1996;70:4805–4810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4805-4810.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christ M, Lusky M, Stoeckel F, Dreyer D, Dieterlé A, Michou A I, Pavirani A, Mehtali M. Gene therapy with recombinant adenovirus vectors: evaluation of the host immune response. Immunol Lett. 1997;57:19–25. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(97)00049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christ, M., et al. Submitted for publication.

- 16.Chroboczek J, Bieber F, Jacrot B. The sequence of the genome of adenovirus type 5 and its comparison with the genome of adenovirus type 2. Virology. 1992;186:280–285. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90082-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clayman G L, El-Naggar A K, Lippman S M, Henderson Y C, Frederick M, Merritt J A, Zumstein L A, Timmons T M, Liu T J, Ginsberg L, Roth J A, Hong W K, Bruso P, Goepfert H. Adenovirus-mediated p53 gene transfer in patients with advanced recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2221–2232. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.6.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connelly S, Smith T A G, Dhir G, Gardner J M, Mehaffey M G, Zaret K S, McLelland A, Kaleko M. In vivo gene delivery and expression of physiological levels of functional human factor VIII in mice. Hum Gene Ther. 1995;6:185–193. doi: 10.1089/hum.1995.6.2-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crystal R G, McElvaney N G, Rosenfeld M A, Chu C-S, Mastrangeli A, Hay J G, Brody S L, Jaffe H A, Eissa N T, Daniel C. Administration of an adenovirus containing the human CFTR cDNA to the respiratory tract of individuals with cystic fibrosis. Nat Genet. 1994;8:42–51. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Czerkinsky C C, Nilsson L-A, Nygren H, Ouchterlony O, Tarkowski A. A solid-phase enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay for enumeration of specific antibody-secreting cells. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:109–121. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai Y, Schwarz E M, Gu D, Zhang W W, Sarvetnick N, Verma I M. Cellular and humoral immune responses to adenoviral vectors containing factor IX gene: tolerization of factor IX and vector antigens allows for long-term expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1401–1405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dedieu J-F, Vigne E, Torrent C, Jullien C, Mahfouz I, Caillaud J M, Aubailly N, Orisini C, Guillaume J M, Opolon P, Delaère P, Perricaudet M, Yeh P. Long-term gene delivery into the livers of immunocompetent mice with E1/E4-defective adenoviruses. J Virol. 1997;71:4626–4637. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4626-4637.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doucas V, Ishov A M, Romo A, Juguilon H, Weitzman M D, Evans R M, Maul G G. Adenovirus replication is coupled with dynamic properties of the PML nuclear structure. Genes Dev. 1996;10:196–207. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dyck I A, Maul G G, Miller W, Chen J D, Jr, Kakizuka A, Evans R M. A novel macromolecular structure is a target of the promyelocyte-retinoic acid receptor oncoprotein. Cell. 1994;76:333–343. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engelhardt J F, Litzky L, Wilson J M. Prolonged transgene expression in cotton rat lung with recombinant adenoviruses in E2a. Hum Gene Ther. 1994;5:1217–1229. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.10-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fang B, Wang H, Gordon G, Bellinger D A, Read M S, Brinkhous K M, Woo S L C, Eisensmith R C. Lack of persistence of E1- recombinant adenoviral vectors containing a temperature-sensitive E2A mutation in immunocompetent mice and hemophilia B dogs. Gene Ther. 1996;3:217–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gahéry-Ségard H, Molinier-Frenkel V, Le Boulaire C, Saulnier P, Opolon P, Lengagne R, Gautier E, Le Cesne A, Zitvogel L, Venet A, Schatz C, Courtney M, Le Chevalier T, Tursz T, Guillet J G, Farace F. Phase I trial of recombinant adenovirus gene transfer in lung cancer. Longitudinal study of the immune response to transgene and viral products. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:2218–2226. doi: 10.1172/JCI119759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao G P, Yang Y, Wilson J M. Biology of adenovirus vectors with E1 and E4 deletions for liver-directed gene therapy. J Virol. 1996;70:8934–8943. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8934-8943.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorziglia M I, Kadan M J, Yei S, Lim J, Lee G M, Luthra R, Trapnell B C. Elimination of both E1 and E2a from adenovirus vectors further improves prospects for in vivo human gene therapy. J Virol. 1996;70:4173–4178. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.4173-4178.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham F L, Prevec L. Adenovirus based expression vectors and recombinant vaccines. In: Ellis R W, editor. Vaccines: new approaches to immunological problems. Newton, Mass: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1992. pp. 363–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grave, L., et al. Submitted for publication.

- 32.Guérin E, Ludwig M-G, Basset P, Anglard P. Stromelysin-3 induction and interstitial collagenase repression by retinoic acid. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11088–11095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang M-M, Hearing P. Adenovirus early region 4 encodes two gene products with redundant effects in lytic infection. J Virol. 1989;63:2605–2615. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2605-2615.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang M-M, Hearing P. The adenovirus early region 4 open reading frame 6/7 protein regulates the DNA binding activity of the cellular transcription factor E2F, through a direct complex. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1699–1710. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.11.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kass-Eissler A, Falck-Pedersen E, Elfenbein D H, Alvira M, Buttrick P M, Leinwand L A. The impact of development stage, route of administration, and the immune system on adenovirus-mediated gene transfer. Gene Ther. 1994;1:395–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kleinberger T, Shenk T. Adenovirus E4orf4 protein binds to protein phosphatase 2A, and the complex down regulates E1A-enhanced junB transcription. J Virol. 1993;67:7556–7560. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7556-7560.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lavoie J N, Nguyen M, Marcellus R C, Branton P E, Shore G C. E4orf4, a novel adenovirus death factor that induces p53-independent apoptosis by a pathway which is not inhibited by zVAD-fmk. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:637–645. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leppard K N. E4 gene function in adenovirus, adenovirus-vector and adeno-associated virus infections. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:2131–2138. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-9-2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Q, Kay M A, Finegold M, Stratford-Perricaudet L D, Woo S L. Assessment of recombinant adenoviral vectors for hepatic gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 1993;4:403–409. doi: 10.1089/hum.1993.4.4-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lusky M, Christ M, Rittner K, Dieterlé A, Dreyer D, Mourot B, Schultz H, Stoeckel F, Pavirani A, Mehtali M. In vitro and in vivo biology of recombinant adenovirus vectors with E1, E1/E2A, or E1/E4 deleted. J Virol. 1998;72:2022–2032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2022-2032.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lusky, M. Unpublished data.

- 42.Marcellus R C, Lavoie J N, Boivin D, Shore G C, Ketner G, Branton P E. The early region 4 orf4 protein of human adenovirus type 5 induces p53-independent cell death by apoptosis. J Virol. 1998;72:7144–7153. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7144-7153.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michou A I, Santoro L, Christ M, Julliard V, Pavirani A, Mehtali M. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer: influence of transgene, mouse strain and type of immune response on persistence of transgene expression. Gene Ther. 1997;4:473–482. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mittereder N, March K L, Trapnell B C. Evaluation of the concentration and bioactivity of adenovectors for gene therapy. J Virol. 1996;70:7498–7509. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7498-7509.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morral N, O’Neal W, Zhou H, Langston C, Beaudet A. Immune responses to reporter proteins and high viral dose limit duration of expression with adenoviral vectors: comparison of E2a wild type and E2a deleted vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:1275–1286. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.10-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Müller U, Kleinberger T, Shenk T. Adenovirus E4orf4 reduces phosphorylation of c-Fos and E1A proteins while simultaneously reducing the level of AP-1. J Virol. 1992;66:5867–5878. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.10.5867-5878.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nabel E G, Pompili V J, Plautz G E, Nabel G J. Gene transfer and vascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;35:422–430. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nordqvist K, Öhman K, Akusjärvi G. Human adenovirus encodes two proteins which have opposite effects on accumulation of alternatively spliced mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:437–445. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohman K, Nordqvist K, Akusjärvi G. Two adenovirus proteins with redundant activities in virus growth facilitate tripartite leader mRNA accumulation. Virology. 1993;194:50–58. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Neal W K, Zhou H, Morral N, Aguilar-Cordova E, Pestaner J, Langston C, Mull B, Wang Y, Beaudet A L, Lee B. Toxicological comparison of E2a-deleted and first-generation adenoviral vectors expressing alpha1-antitrypsin after systemic delivery. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:1587–1598. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.11-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Otake K, Ennist D L, Harrod K, Trapnell B C. Non-specific inflammation inhibits adenovirus-mediated pulmonary gene transfer and expression independent of specific acquired immune responses. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;10:2207–2222. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.15-2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scaria A, St. George J A, Jiang C, Kaplan J M, Wadsworth S C, Gregory R J. Adenovirus-mediated persistent cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator expression in mouse airway epithelium. J Virol. 1998;72:7302–7309. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7302-7309.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schuler M, Roschlitz C, Horowitz J A, Schlegel J, Perruchoud A P, Kommoss F, Bolliger C T, Kauczor H U, Dalquen P, Fritz M A, Swanson S, Hermann R, Huber C. A phase I study of adenovirus-mediated wild-type p53 gene transfer in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;14:2075–2082. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.14-2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shenk T. Adenoviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, et al., editors. Virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Raven Press; 1996. pp. 2111–2148. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shtrichman R, Kleinberger T. Adenovirus type 5 E4 open reading frame 4 protein induces apoptosis in transformed cells. J Virol. 1998;72:2975–2982. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2975-2982.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith T A G, Mehaffey M G, Kayda D B, Saunders J M, Yei S, Trapnell B C, McLelland A, Kaleko M. Adenovirus mediated expression of therapeutic plasma levels of human factor IX in mice. Nat Genet. 1993;5:392–402. doi: 10.1038/ng1293-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trapnell B C. Adenoviral vectors for gene transfer. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 1993;12:185–199. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tripathy S K, Black H B, Goldwasser E, Leiden J M. Immune responses to transgene-encoded proteins limit the stability of gene expression after injection of replication-defective adenovirus vectors. Nat Med. 1996;2:545–550. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Virtanen A, Gillardi P, Naslund A, Lemoullec J M, Pettersson U, Perricaudet M. mRNAs from human adenovirus 2 early region 4. J Virol. 1984;51:822–831. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.3.822-831.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Q, Greenburg G, Bunch D, Farson D, Finer M H. Persistent transgene expression in mouse liver following in vivo gene transfer with a ΔE1/ΔE4 adenovirus vector. Gene Ther. 1997;4:393–400. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang Y, Jooss K U, Su Q, Ertl H C J, Wilson J M. Immune responses to viral antigens versus transgene product in the elimination of recombinant adenovirus-infected hepatocytes in vivo. Gene Ther. 1996;3:137–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yao S N, Farjo A, Roessler B J, Davidson B L, Kurachi K. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of human factor IX gene in immunodeficient and normal mice: evidence for prolonged stability and activity of the transgene in liver. Vir Immunol. 1996;9:141–153. doi: 10.1089/vim.1996.9.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yeh P, Dedieu J F, Orsini C, Vigne E, Denefle P, Perricaudet M. Efficient dual transcomplementation of adenovirus E1 and E4 regions from a 293-derived cell line expressing a minimal E4 functional unit. J Virol. 1996;70:559–565. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.559-565.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zabner J, Ramsey B W, Meeker D P, Aitken M L, Balfour R P, Gibson R L, Launspach I, Moscicki R A, Richards S M, Standaert T A, Williams-Warren J, Wadsworth S C, Smith A E, Welsh M J. Repeat administration of an adenovirus vector encoding cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator to the nasal epithelium of patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Investig. 1996;97:1504–1511. doi: 10.1172/JCI118573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]