Summary

Background

Induction of donor-specific tolerance is a promising approach to achieve long-term graft patency in transplantation with little to no maintenance immunosuppression. Changes to the recipient’s T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire are understood to play a pivotal role in the establishment of a robust state of tolerance in chimerism-based transplantation protocols.

Methods

We investigated changes to the TCR repertoires of patients participating in an ongoing prospective, controlled, phase I/IIa trial designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of combination cell therapy in living donor kidney transplantation. Using high-throughput sequencing, we characterized the repertoires of six kidney recipients who also received bone marrow from the same donor (CKBMT), together with an infusion of polyclonal autologous Treg cells instead of myelosuppression.

Findings

Patients undergoing combination cell therapy exhibited partial clonal deletion of donor-reactive CD4+ T cells at one, three, and six months post-transplant, compared to control patients receiving the same immunosuppression regimen but no cell therapy (p = 0.024). The clonality, R20 and turnover rates of the CD4+ and CD8+ TCR repertoires were comparable in both groups, showing our protocol caused no excessive repertoire shift or loss of diversity. Treg clonality was lower in the case group than in control (p = 0.033), suggesting combination cell therapy helps to preserve Treg diversity.

Interpretation

Overall, our data indicate that combining Treg cell therapy with CKBMT dampens the alloimmune response to transplanted kidneys in humans in the absence of myelosuppression.

Funding

This study was funded by the Vienna Science and Technology Fund (WWTF).

Keywords: T cell receptor, Alloreactivity, Kidney transplantation, Cell therapy, Immunological tolerance

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

A longstanding aim of transplantation medicine is the establishment of donor-specific tolerance, a state wherein immune-mediated injury to the transplanted organ is prevented while the immune system remains competent to respond to pathogens and tumors. This could not only minimize the chances of organ rejection but also alleviate the need for prolonged immunosuppressive treatments and their associated side-effects. Tolerance has been achieved in kidney transplant recipients through the co-transplantation of bone marrow from the same donor (CKBMT), but such protocols are not yet ready for widespread clinical application, partly because of unresolved safety concerns linked to the necessary conditioning of the recipient by means of irradiation, such as the possible occurrence of graft-vs-host disease (GVHD).

Added value of this study

In this study, we explored the potential of a CKBMT protocol wherein bone marrow engraftment is promoted through an infusion of T regulatory (Treg) cells, an alternative to irradiation which should substantially improve the safety of recipient conditioning. Specifically, we investigated changes to the recipients’ repertoire of T cells, the primary mediators of immune responses in transplantation, and identified which clonotypes reacted to donor antigens. Our study shows such donor-reactive clonotypes selectively expanded in blood samples of control patients, but not in the blood of our CKBMT patients. This difference was consistently observed at one, three, and six months after transplant, offering a strong indication of early pro-tolerogenic modulation in our case group. Further, our results show the CKBMT protocol caused no major shift or loss of diversity to the repertoires, which speaks to its safety.

Implications of all the available evidence

The induction of donor-specific tolerance has the potential to transform transplant medicine. Our study tests in a clinical setting the hypothesis that an infusion of recipient Treg cells can promote it without the need for myelosuppression or the associated high risk of GVHD. By supporting this hypothesis, the work presented here advances our understanding of immune responses in humans and invites further study into this therapeutic approach as a promising avenue in transplantation.

Introduction

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is a growing public health epidemic with substantial impact on longevity and quality of life.1 Kidney transplantation, which prolongs life across all age groups and restores quality of life, has emerged as the treatment of choice.2,3

Over the last few decades, significant improvements to short-term transplantation outcomes have been achieved, with the current standard of care proving highly effective in preventing early acute T cell-mediated rejection (TCMR) of allografts. Long-term functional graft survival has also improved but not to the same extent,4 partly due to the side-effects of immunosuppressive drugs.5 Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) are the mainstay of maintenance immunosuppression after kidney transplantation but exhibit dose-dependent nephrotoxicity.6 Moreover, prolonged immunosuppression increases susceptibility to infections, malignancies and cardiovascular disease, which place a serious burden on transplant recipients that do retain their grafts, while contributing to elevated standardized mortality ratios.7,8 On the other hand, non-adherence to treatment, which occurs in roughly a third of cases, is a major cause of late graft attrition and particularly detrimental to patients with poor Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) class II epitope matches.9

It is clear that new approaches are needed to prolong graft and patient survival with no or only minimal maintenance immunosuppression. The establishment of donor-specific immunological tolerance, a state wherein the immune system does not reject the graft but remains otherwise intact, has thus become the holy grail in solid organ transplantation. It has been achieved in several pilot trials by combining kidney and bone marrow transplantation (CKBMT), a protocol designed to induce transient mixed-chimerism.10, 11, 12 These prospective studies constitute proof-of-principle, but their use of myelosuppressive recipient conditioning to promote bone marrow engraftment discourages widespread clinical application.

Over recent years, we have investigated the possibility of attaining engraftment via the administration of polyclonal recipient Tregs, leading to a non-myelosuppressive option that could substantially improve the safety of tolerance induction protocols.13, 14, 15 In an ongoing study, we are evaluating this form of combination cell therapy in a clinical setting. The final clinical results will be available in a separate paper; here, we set out to characterize the recipients’ repertoire of T cells during the first six months after transplant. T cells are the primary mediators of immune responses in transplantation; changes to the shape and diversity of their population, namely the deletion of donor-reactive clones, are thought to contribute to the establishment of a robust state of tolerance in chimerism-based transplantation protocols.16 Using high-throughput T cell receptor (TCR) sequencing, we compare the repertoires of six case patients to those of a control group receiving the same immunosuppression regimen but no cell therapy, probing for early signs pro-tolerogenic modulation.

Methods

Study design

Samples were collected from patients participating in an ongoing open-labeled, controlled, single-center academic phase I/IIa trial. The study design is summarized in Fig. 1A. The detailed protocol, including information on subject recruitment, treatment allocation and sample size calculation, was previously published.17 The first and last subjects were enrolled in September 2019 and June 2023, respectively; detailed subject characteristics are listed in Table 1. In brief, 12 ABO compatible, HLA-mismatched living donor kidney transplant recipients were assigned to one of two treatment groups. Mean recipient age was 40.5 ± 14.6 and 49.8 ± 14.5, for the case and control groups, respectively. Sex assigned at birth was not considered as a biological co-variable and was thus not a criterion in subject selection. None of the study participants exhibited preformed antibodies against the donor’s HLA. Post-transplantation, six recipients in the “case” group received in vitro expanded autologous Treg cells and a donor bone marrow cell infusion within the first three days, as well as tocilizumab for the first three weeks (combination cell therapy). Six control recipients did not receive Tregs, bone marrow or tocilizumab; all participants received anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) Thymoglobulin® induction and maintenance immunosuppression in the first six months consisting of belatacept, sirolimus, and steroids.

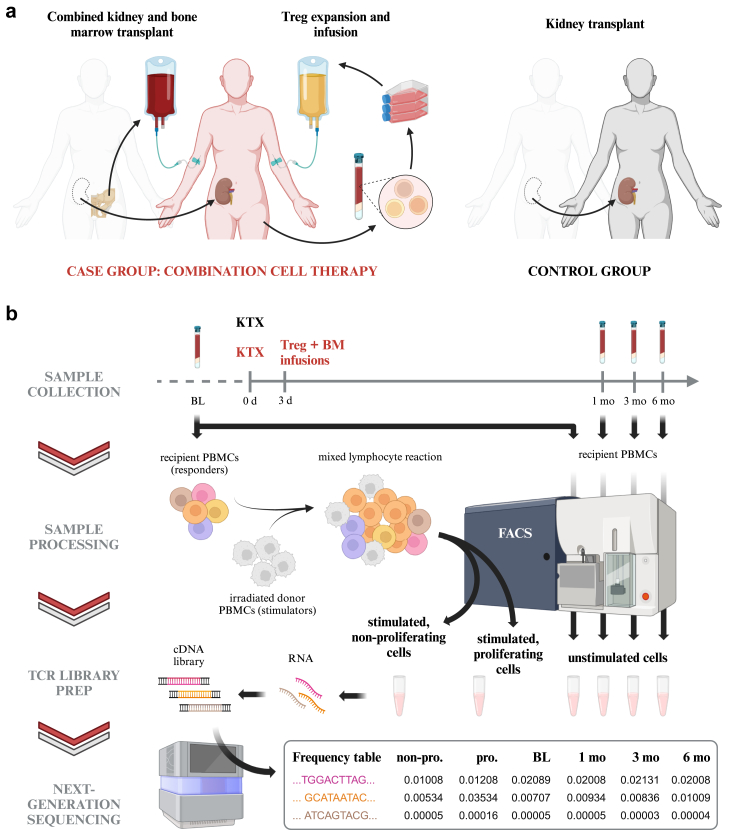

Fig. 1.

Summary of study design and experimental workflow.(a) A total of 12 living donor kidney transplant recipients participated in a prospective, controlled phase I/IIa trial designed to test a combination cell therapy protocol.17 Within three days after the transplant, six patients assigned to the case group received bone marrow from the same donor and an infusion of in vitro expanded autologous Treg cells. Six kidney transplant recipients in the control group received neither bone marrow nor Tregs. (b) Blood samples were collected from all recipients for TCR repertoire monitoring at one, three, and six months post-transplant. Isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were then sorted into three unstimulated lymphocyte populations (CD4+, CD8+ and Treg) by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; see Supplementary Fig. S1A for the gating strategy). PBMCs collected pre-transplant were either processed as described above to establish baseline (BL) TCR repertoires or co-cultured for six days with irradiated donor cells in a mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR). Recipient cells stimulated in an MLR were sorted by FACS into the populations listed above and, in parallel, into proliferating and non-proliferating cells (see Supplementary Fig. S1B for the gating strategy). RNA isolated from all sorted samples was used as template for preparation of TCR cDNA libraries for next-generation sequencing. The frequency of each unique TCR sequence (clonotype) was computed from the assembled sequencing reads. See Methods for details. Illustrations created with BioRender.com.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants.

| Sex | Age at TX | Etiology of ESRD | CMV (IgG/IgM) | HLA MM (A-B-C-DR-DQ) | Donor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient #1 | M | 32 | VUR | +/+ | 1-0-0-0-0 | LRD |

| Patient #2 | M | 37 | IgA-Nephritis | +/− | 1-1-0-1-1 | LRD |

| Patient #3 | M | 54 | unknown | +/− | 1-1-1-2-2 | LURD |

| Patient #4 | M | 30 | IgA-Nephritis | +/− | 2-2-1-2-1 | LURD |

| Patient #5 | M | 27 | VUR | −/− | 0-1-1-1-0 | LRD |

| Patient #6 | M | 63 | unknown | +/− | 1-2-1-1-1 | LURD |

| Control #1 | M | 40 | ADPKD | −/− | 0-1-1-1-0 | LRD |

| Control #2 | M | 25 | VUR | −/− | 1-1-0-1-1 | LRD |

| Control #3 | M | 56 | ADPKD | +/− | 2-2-2-2-1 | LURD |

| Control #4 | M | 62 | ICGN | +/− | 1-2-1-2-1 | LURD |

| Control #5 | M | 61 | PKD | +/− | 1-1-1-2-1 | LRD |

| Control #6 | M | 55 | ICGN | +/− | 2-1-1-2-2 | LURD |

ESRD, End-stage renal disease; VUR, Vesicoureteral reflux; ADPKD, Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease; ICGN, immune-complex glomerulonephritis; PKD, Polycystic Kidney Disease; CMV, Cytomegalovirus; HLA MM, Human leukocyte antigen mismatch; LDR, Living related donor; LURD, Living unrelated donor.

Co-primary endpoints of safety (impaired graft function [eGFR < 35 mL/min/1.73 m2], graft-vs-host disease or patient death by 12 months) and efficacy (total leukocyte donor chimerism within 28 days post-transplant) were assessed. Secondary objectives included the monitoring of changes to the immune system, namely to the TCR repertoire.

Sample collection

Control subject #5 decided to abandon the study at 3 months post-transplant and was hence excluded from sample collection and analysis thereafter. We were unable to harvest sufficient cells from control subject #3 for TCR library preparation and subsequent investigation (see Supplementary Table S1 for the number of cells sorted).

As part of the routine follow up at the outpatient clinic, blood samples for TCR repertoire monitoring were collected into BD Vacutainer CPT tubes (Becton, Dickinson and Company cat. #362753) at one month (28 ± 3 days), three months (±2 weeks) and six months (±4 weeks) post-transplant. Baseline samples were collected from control and case recipients before transplant and before ATG induction, respectively, as well as from donors before transplant. CPT tubes were processed following the manufacturer’s protocol and isolated cells were either cryopreserved for future processing or immediately sorted as detailed below (Fig. 1B).

Mixed lymphocyte reaction

To define the alloreactive TCR repertoire, a donor-stimulated cell population was generated as described previously.18,19 In brief, cryopreserved recipient PBMCs collected pre-transplant were thawed, labeled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Invitrogen cat. #C34554), washed twice and finally resuspended in MLR medium at 2 × 106 cells/mL. Donor PBMCs were likewise thawed, then labeled with Violet Proliferation Dye 450 (VPD-450, BD Horizon cat. #562158, Research Resource Identifier (RRID): AB_2869398), washed and irradiated. Mixed Lymphocyte Reactions (MLR) were performed by co-culturing 2 × 105 CFSE-labeled cells (“responders”) with 2 × 105 VPD-labeled cells (“stimulators”) in each well of a 96-well plate. After six days incubation at 37 °C (relative humidity 95% with 5% CO2), the responder cells were separated into CD4+ and CD8+ populations using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) as detailed below. Further, CFSElow (i.e., proliferating) cells were sorted from those that were CFSEhigh, and the relative size of the first population taken as a measurement of in vitro reactivity.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

FACS was used to separate cells into CD4+, CD8+ and Treg T-cell fractions from all pre- and post-transplant timepoints and to obtain CD4+ and CD8+ donor reactive and non-donor reactive cells from MLRs. Either freshly isolated PBMCs or previously cryopreserved PBMCs were used as starting material for sorting of native cells. In case of freshly isolated PBMCs, cells were pelleted after the last washing step by centrifugation at 250g for 10 min, the supernatant was discarded and the cells were resuspended in FACS buffer (1xPBS with 2%FBS) at a final concentration of 1 × 107 cells/mL for subsequent staining. Cryopreserved cells were rapidly thawed in a 37 °C water bath and the cell suspension was slowly diluted with prewarmed cell culture medium to reduce the dimethyl sulfoxide concentration. Immediately after, cells were collected by centrifugation at 250g for 10 min and the supernatant was discarded. Cells were resuspended in fresh prewarmed cell culture medium at a concentration of 1.5 × 106 cells/mL, plated into 6-well plates and incubated overnight in a cell culture incubator at 37 °C, relative humidity 95% with 5% CO2. On the next day, cells were harvested into a 15 mL test tube, diluted with ice cold PBS, pelleted by centrifugation at 250g for 10 min and resuspended in FACS buffer at a final concentration of 1 × 107 cells/mL for subsequent staining. Cells from MLRs were prepared following the same steps. For staining the following fluorescent labeled antibodies against CD3 (PerCP-Cy5.5; 2.5 μL per test; BD Pharmingen cat. #552852, RRID: AB_394493), CD4 (AF700; 1.3 μL per test; BioLegend cat. #317426, RRID: AB_571943), CD8 (APC-Cy7; 5 μL per test; BD Pharmingen cat. #557834, RRID: AB_396892), CD25 (PE; 10 μL per test; BD cat. # 341011, RRID: AB_2783790) and CD127 (AF647; 5 μL per test; BD Pharmingen cat. #558598, RRID: AB_647113) were added to the before prepared cells and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark. In case of MLRs antibodies against CD25 and CD127 were omitted. Subsequently, cells were washed once by diluting the cell suspension with ice cold FACS buffer followed by pelletization through means of centrifugation at 250g for 10 min, removal of the supernatant and resuspension of cells at a final concentration of approximately 2 × 107 cells/mL. Immediately prior to sorting the cell suspension was passed through a 35 μm cell strainer. Cells were acquired on a FACS Aria Fusion equipped with a 70 μm nozzle. Lymphocytes were determined by forward and side scatter and doublets were excluded based on forward scatter height and area. From the remaining singlets CD3+ cells were identified and gated into CD4+ (CD4+ T-cells) and CD8+ (CD8+ T-cells) cells. CD4+ T-cells were further divided into Treg cells (CD25+ and CD127low) and non-Treg cells. Treg, CD4+ (non-Treg) T-cells and CD8+ T-cells were sorted into separate test tubes.

For sorting proliferating and non-proliferating cells from MLRs the gating scheme was extended to exclude stimulator cells based on their VPD staining and to identify CFSElow and CFSEhigh cell populations among the CD3+ population. A total of four boolean and gates intersecting CD4+ and CD8+ gates with proliferating and non-proliferating cell gates were set up to sort alloreactive CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells as well as CD4+ and CD8+ non-alloreactive T-cells into separate test tubes. All sorting were carried out using four-way sort purity. Sorted cells were divided into 250 μL aliquots preserving the ratios between the different T-cell populations. Lastly, cells were lysed by adding 750 μL Trizol LS (Invitrogen cat. #10296028) to each aliquot and stored at −20 °C until further processing. Exemplary gating schemes are provided in Supplementary Fig. S1. The number of cells sorted from each blood sample are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

TCR library preparation and sequencing

RNA was isolated from sorted lymphocyte populations following the original TRIzol protocol (Invitrogen) and used as template for NGS library preparation using the immune profiling kit SMART-Seq Human TCR (with unique molecular identifiers [UMI]) (Takara Bio, cat. #6347801). Libraries of the TCR β-chain repertoire were prepared following manufacturer’s instructions, spiked with 15% PhiX (Illumina cat. #FC-110-3001) and sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq 2000 platform. BCL Convert (Illumina) was used to process the resulting binary base call (BCL) files into per sample fastq file sets. UMI processing and clonotype assembly was performed using the Cogent NGS Immune Profiler software (Takara Bio), version 1.6.

The number of reads obtained after assembly, error correction and molecular identifier group (MIG) collapse (hereafter referred to as captured molecules) are detailed in Supplementary Table S2. For unstimulated samples, they showed a strong linear correlation with the number of cells used for RNA isolation (Supplementary Fig. S2A), indicating that every cell had a similar probability of being sampled. A significantly larger number of molecules was captured from cells in the proliferating fraction of MLRs, likely reflecting their increased transcriptional activity (Supplementary Fig. S2B).

TCR repertoire processing

TCR repertoire processing and subsequent analysis were performed with the statistical software R version 4.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). For each unique TCR β-chain sequence (clonotype) the following information was retained for further study: complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) amino acid and nucleotide sequences, (molecule) count, frequency, and the most likely V, D, and J genes. Since it is extremely unlikely that a TCD4 and a TCD8 cell have the same CDR3 sequence, clonotypes detected in more than one sorted population were assumed to indicate sorting errors. These were corrected whenever possible by assigning the shared sequences to the lineage in which the total count across all timepoints doubled the others. If no lineage met this frequency threshold, clonotypes were deemed ambiguous and dropped from the repertoire. Corresponding frequency adjustments were carried out. To correct for possible bias due to differences in the number of captured T-cells, the repertoires were, unless otherwise specified, downsampled to the lowest molecule count within each lineage and patient (listed in Supplementary Table S2). All presented results are based on the mean estimates derived from 100 downsampled repertoires.20

TCR repertoire comparison and diversity analysis

In each subject, changes in number of clonotypes (NC) relative to baseline (BL) were quantified as a ratio (fold-change): , for each post-transplant time-point (postTX).

The Jensen–Shannon divergence (JSD), a measure quantifying the similarity between two probability distributions, was employed to compare pairs of TCR repertoires in terms of CDR3 nucleotide sequences.20 The JSD ranges from 0 (for two identical repertoires) to 1 (in case of no overlap). Either the top 1000 ranked clonotypes or the entirety of sequenced repertoires was compared, as stated where pertinent.

We characterized the diversity of each TCR repertoire using two metrics, as follows:

-

(i)

Clonality (C) is a measure of normalized diversity derived from Shannon’s entropy (Hobs): ,21 where Hmax is the maximum entropy possible for the observed sample space (i.e., that of a repertoire where every clonotype appears with the exact same frequency). C = 0 thus denotes maximal diversity, whereas a pool of identical clones would have a clonality of “1”.

-

(ii)

R20 is the fraction of the clonotypes, in descending order of frequency, that together account for 20% of the whole repertoire. A small R20 value indicates immunodominance of a subset of clonotypes.

Because these metrics are bound between 0 and 1, changes relative to baseline (BL) were directly quantified in terms of and , for each post-transplant time-point (postTX).

Alloreactivity analysis

Clonotypes were classified as alloreactive if their frequency in the proliferating fraction of the donor-stimulated pre-transplant sample (see above, Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction) was at least 10−5 and also ≥5-fold greater than in the unstimulated pre-transplant (“baseline”) sample. This fold expansion criterion has been previously used in similar studies to exclude the effects of bystander activation that may occur during the later phase of the MLR.18,22,23

The alloreactive fraction of a TCR repertoire (AlloF) was defined as the cumulative sum of the frequencies of all clonotypes classified as alloreactive. To quantify the specific expansion of these clonotypes, a relative measure of alloreactive load (AlloL) was derived by normalizing AlloF to the summed frequencies of a set of clonotypes randomly sampled from the entire repertoire of donor-stimulated cells (both proliferating and non-proliferating). Changes relative to baseline (BL) were quantified as a ratio: , for each post-transplant time-point (postTX).

Statistics

Overall changes to the number of clonotypes, Clonality and R20 were first investigated by using Friedman tests to detect differences between time-points, across all study subjects irrespective of treatment group. Differences were deemed significant at a p-value of less than 0.05. To compare values between groups in the metrics for repertoire diversity, turnover and alloreactivity we employed mixed models for repeated measurements (MMRM).24 Such models account for the within-participant correlation of longitudinal outcome measurements. For each metric of interest, the values for each participant at each timepoint constituted the outcome variables of the models. To ensure that modeling assumptions for inference were met (i.e., normality of residuals and homoscedasticity) we transformed the outcome variable for several metrics by the base-2 logarithm. As covariates, we included the group allocation (case vs control), the timepoint of the measurement (coded by a categorical variable with levels “Baseline”, “1 Month”, “3 Months”, “6 Months”), as well as a group-by-timepoint interaction to increase statistical efficiency.25 Due to the limited sample size we did not adjust for further covariates. We chose an unstructured covariance matrix for the timepoints within participants. As sensitivity analysis we assessed other choices for the covariance matrices such as autoregressive or ante-dependence structures via the Akaike information criterion. Generally, we found structured covariance matrices to be too restrictive to account for the variability across timepoints. Models were fitted using maximum likelihood to facilitate such comparisons. We checked the modeling assumptions via calibration plots and residual diagnostics (quantile-quantile plots and plotting fitted values vs residuals). From the fitted MMRMs we obtained estimated marginal means for both groups and all timepoints, and derived p-values for an overall group difference (averaging across timepoints) as well as timepoint-specific contrasts. Inference was based on a sandwich estimator of the variance-covariance matrix for the coefficients and the Satterthwaite approximation for the degrees of freedom. Measured differences were deemed significant at a p-value of less than 0.05. Unless otherwise stated, p-values were not adjusted for multiple testing due to the exploratory nature of the statistical analysis. There was no missing data or loss to follow up in this study. We implemented the statistical analyses in the statistical software R (version 4.3.1) using the packages mmrm and emmeans to fit the MMRMs and obtain test statistics, respectively.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK Nr: 1871/2018) and the Austrian Federal Office for Safety in Health Care (BASG Bundesamt für Sicherheit im Gesundheitswesen, Verfahrensnummer 11337515). It was registered in a public clinical trial database on 06-03-2019 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03867617). All study participants provided written informed consent before study entry.

Role of the funding source

The Vienna Science and Technology Fund (WWTF) provided financial support and had no influence on the design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, nor on the writing of the manuscript.

Results

Overall changes to TCR repertoires post-transplant

To monitor changes to the TCR repertoires of study participants, RNA was isolated from unstimulated cells sampled before transplant and at one, three, and six months post-transplant (Fig. 1B). The number of unique TCR β-chains (clonotypes) detected by Next-generation sequencing (NGS) in CD4+, CD8+ and Treg cell populations ranged from 3.786 to 245.953, 2.225 to 115.301 and 313 to 30.050, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). For several subjects, clonotype count was observed to correlate linearly with the number of molecules captured, which was in turn a function of the input cell number (Supplementary Fig. S2A and C). While expected, this correlation speaks to the need to downsample all repertoires in a group of interest to the same size before any comparisons can be made. To examine how the number of clonotypes changed after transplant, we hence downsampled the repertoires of each subject to the lowest molecule count across all timepoints. All presented results are based on the mean estimates derived from 100 downsampled repertoires.

The mean clonotype counts, shown in Supplementary Fig. S3A, were found to change significantly over time in CD4+ samples (p < 0.05; Friedman test). While they varied greatly between subjects, normalization to pre-transplant (“baseline”) values revealed that the numbers tended to sharply decrease in the first month post-transplant (to 50.8 ± 33.8%) and subsequently stabilize (Supplementary Fig. S3B). A similar decrease was observed for the Treg cells (60.0 ± 34.1%), but it appeared to be transient. No consistent trend was discernable for CD8+ cells. When subjects were grouped by treatment, no significant differences could be measured for any of the cell populations and time-points (Supplementary Fig. S3C), indicating that combination cell therapy had no outstanding effect on the clonotype counts.

To further investigate potential changes to the TCR repertoire, we computed the Jensen–Shannon divergence (JSD), which quantifies the overlap between pairs of repertoires in a standardized way, taking into account not only the number of shared clonotypes but also their frequency distribution. The top 1000 clonotypes of each post-transplant repertoire were compared to the corresponding pre-transplant baseline (Supplementary Fig. S4A). Because the repertoires of distinct cell lineages were not downsampled to the same molecule count, the JSD values computed for CD4+, CD8+ and Treg cells are not directly comparable. However, the fact that, for both the CD4+ and CD8+ populations, the values approached those measured for non-proliferating cells in Mixed Lymphocyte Reactions (MLR) – populations also sampled before transplant and expected to be all but identical to the baseline suggests an overall low degree of repertoire turnover (Supplementary Fig. S4B).

Interestingly, JSD was observed to be largely subject-specific, varying considerably between individuals but rarely over time (Supplementary Fig. S4A), even when the repertoires of all subjects were downsampled to the same size (Supplementary Fig. S5). Thus, the measured divergence likely reflects the effect of ATG-induced lymphocyte depletion followed by partial recovery within the first month after transplant. Overall, the data hence indicates that kidney recipients in our study experienced a minimal disruption to their CD4+ and CD8+ repertoires. Importantly, such disruptions were, on average, similar in CKBMT patients than in control subjects (Supplementary Fig. S4B).

TCR repertoire diversity

However minor, the measured changes to TCR repertoire composition did amount to, at least among CD4+ lymphocytes, a substantial decrease in the number of unique clonotypes detected. We therefore sought to determine how each treatment impacted TCR repertoire diversity. We could reliably observe a post-transplant increase in clonality (C, see Methods for details) only for CD4+ repertoires (Supplementary Fig. S6A). The effect was statistically significant (p < 0.05; Friedman test) but minor (ΔC = 0.09 ± 0.09 after one month), and no more severe in the case group than it was among control subjects (Fig. 2A). While mean CD8+ clonality was comparatively higher pre-transplant, it did not increase any further (ΔC = 0.02 ± 0.12 after one month). The clonality of the Treg repertoire was markedly low both before and after transplant (Supplementary Fig. S6A). Interestingly, a small increase in mean clonality could be detected in the control group, but not in CKBMT recipients (Fig. 2A). A mixed model for repeated measurements accounting for within-subject correlations over time showed the between-group difference to be statistically significant overall (p = 0.033).

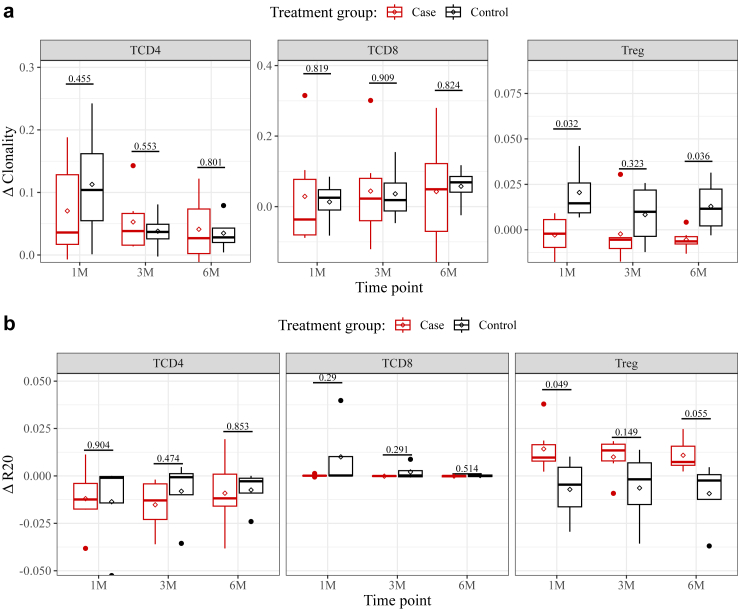

Fig. 2.

Changes to the diversity of TCR repertoires during the first 6 months after kidney transplant. Clonality and R20 were computed on downsampled CD4+, CD8+ and Treg repertoires and then normalized to the pre-transplant baseline, such that a delta-value of 0 denotes no change. Boxplots of (a) Clonality and (b) R20 delta-values, grouped by treatment group. Above, p-values derived for each time-point from a Mixed Model for Repeated Measurements (MMRM), contrasting the means of the two groups. Across all timepoints, p = 0.033). Lines and diamonds denote median and mean values, respectively; lower and upper hinges correspond to the first and third quartiles; whiskers extend to the smallest and largest values within 1.5∗IQR. Dots correspond to outlying data points. Non-normalized Clonality and R20 values for each patient are shown in Supplementary Fig. S6A and B, respectively. See Methods for details.

To probe for increased immunodominance of any subset of clonotypes, we next computed the R20, i.e., the fraction of the most frequent clonotypes within a repertoire that cumulatively makes up 20% of the whole (see Methods for details). Over time, no clear trend could be discerned for any of the three cell phenotypes analyzed (Supplementary Fig. S6B). As previously reported,22 the mean R20 of CD8+ repertoires was considerably lower than that measured in CD4+ samples, signifying a relatively high immunodominance. Conversely, the Treg population presented on average the highest R20 values. Grouping subjects by treatment group (Fig. 2B) furthermore showed that, in Treg cells of CKBMT recipients alone, R20 increased slightly after transplant (ΔR20 = 0.014 ± 0.013 after one month). These results were generally consistent with our clonality estimates, revealing known differences in diversity between the three cell types analyzed but showing combination cell therapy to have no significant impact on the overall shapes of the CD4+ and CD8+ TCR repertoires. Tregs samples, on the other hand, tended to exhibit increased diversity in our case group.

Alloreactivity

We next sought to specifically analyze the abundance of alloreactive clones within sequenced TCR repertoires, and how it evolved after transplant. For every recipient, alloreactive clones were expanded in vitro by stimulating PBMCs isolated pre-transplant with donor cells, in a Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction (MLR, see Methods for details). In vitro reactivity, i.e., the relative proliferation of stimulated cells, averaged 38.1 ± 12.1% and 52.8 ± 22.2% in CD4+ and CD8+ populations, respectively (cell counts are detailed in Supplementary Table S1). Case subject #1 presented the lowest values for both populations (18.5 and 5.8%) and we were in fact unable to sort enough proliferating cells for RNA isolation and subsequent library preparation. This singularly low reactivity is perhaps expected, given that this patient-donor pair had a single HLA mismatch, the lowest number among all study participants. Indeed, we found in vitro reactivity to correlate with the number of class-specific HLA mismatches (p < 0.01, Pearson correlation test; Supplementary Fig. S7A). High-resolution HLA-matching showed Case subject #1 to have a single mismatched eplet (in HLA-A), when all others had between 10 and 30.

As expected, sequencing the repertoires from cells proliferating after stimulation revealed markedly lower numbers of unique clonotypes, compared to those found in unstimulated samples (Supplementary Fig. S3C and Table S2). To account for the potential effect of bystander activation (i.e., to exclude from the analysis any non-donor-specific T cells proliferating in the later stages of MLRs), we only classified as alloreactive clonotypes that appeared at a frequency increased at least 5-fold (see Methods for details). For most subjects, the absolute numbers of alloreactive clonotypes detected remained fairly constant over time (Supplementary Fig. S7B). While the mean numbers show a small decrease post-transplant in both cell lineages analyzed, we did not observe any significant difference between treatment groups (Supplementary Fig. S7C).

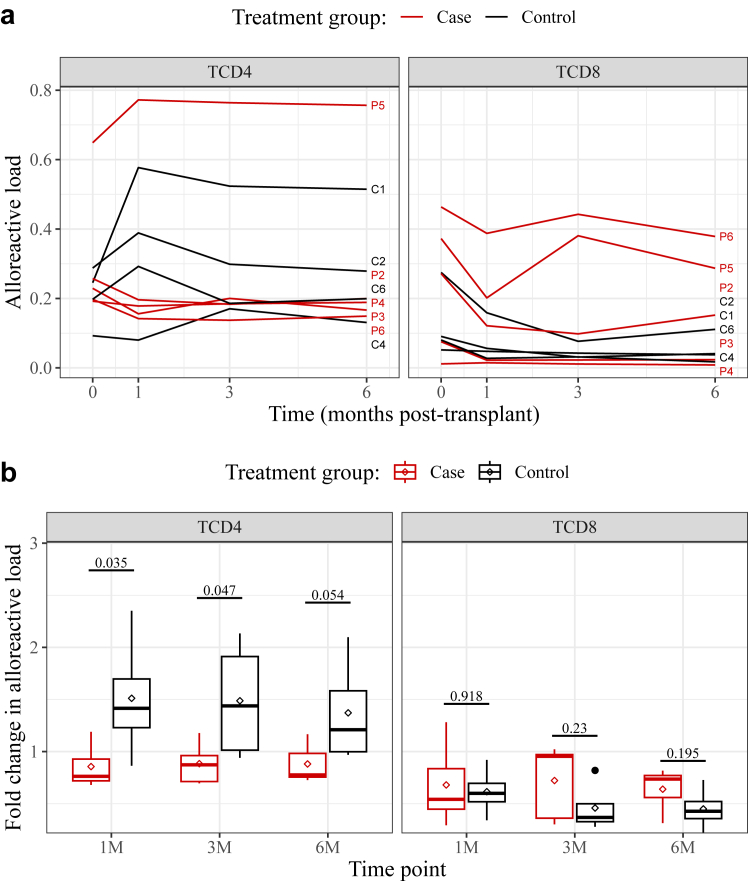

However, the number of alloreactive clonotypes remained fairly constant while the total number of clonotypes declined after transplant (Supplementary Fig. S3B and C). Indeed, we found that the cumulative frequency of all CD4+ alloreactive clonotypes increased in some subjects, indicating that donor-specific T cells accounted for a growing fraction of these repertoires (Supplementary Fig. S8A). While this could result from an expansion of the alloreactive clonotypes, it could also reflect more general changes in repertoire shape, namely the loss of diversity described above (Fig. 2). We therefore sought to determine whether the alloreactive fraction of sequenced repertoires selectively expanded over time. To control for differences in overall repertoire shape, we normalized the total frequency of alloreactive clones (Supplementary Fig. S8A) to that of a randomly sampled clonotype set. The alloreactive “load” thus computed was found to vary considerably between patients (Fig. 3A). It was never observed to increase in post-transplant CD8+ repertoires, but did rise in the CD4+ repertoires of some subjects. Strikingly, this selective expansion of alloreactive CD4+ clonotypes appeared to be largely specific to the control group, in all post-transplant time-points (Fig. 3B): on average, the alloreactive load of CKBMT patients was lower than baseline, while that of conventional transplant recipients was elevated suggesting a reduced alloimmune response in the CKBMT group. The difference was most pronounced one month after transplant, when the mean fold-changes in alloreactive load were measured at 0.86 ± 0.21 for the case group and at 1.51 ± 0.62 for the control group (p = 0.035, MMRM). Over the entirety of the six months, the difference between treatment groups was also statistically significant (p = 0.024, MMRM), and robust against increases to the 5-fold expansion criterion we used to exclude the so-called bystander effect (Supplementary Fig. S8B). These data lend credence to the hypothesis that combination cell therapy leads to partial clonal deletion and suppression of the expansion of alloreactive clonotypes in kidney transplant recipients.

Fig. 3.

Changes to the relative abundance of alloreactive TCR clonotypes during the first 6 months after kidney transplant. Clonotypes identified as alloreactive (i.e., those proliferating once stimulated with donor PBMCs) were detected in CD4+and CD8+ downsampled repertoires. (a) The alloreactive loads were quantified by normalizing the total frequencies of alloreactive clonotypes (shown in Supplementary Fig. S8A) to that of randomly sampled clonotypes, and plotted over time for each study subject, identified as Patient (P) #1–6 or Control (C) #1–6. (b). The alloreactive loads were then normalized to the pre-transplant baseline such that a fold-change of 1 denotes no change. Shown are boxplots comparing the two treatment groups. Above, p-values derived for each time-point from a Mixed Model for Repeated Measurements (MMRM), contrasting the means of the two groups. Across all timepoints, p = 0.024. Lines and diamonds denote median and mean values, respectively; lower and upper hinges correspond to the first and third quartiles; whiskers extend to the smallest and largest values within 1.5∗IQR. Dots correspond to outlying data points.

Discussion

In this study we monitored the circulating TCR repertoires of kidney transplant recipients who received, as part of a tolerance induction protocol, regulatory T cell therapy and donor bone marrow infusion. We could establish that this combination cell therapy does not cause major shifts in the patients’ CD4+ and CD8+ repertoires, as compared to our control group, which speaks to its safety. Importantly, we showed that the diversity of the repopulating T cells did not decrease more than in control subjects, and that neither the number nor relative abundance of alloreactive clonotypes increased. On the contrary, and as discussed in more detail below, we found that combination cell therapy patients presented with reduced clonal expansion of donor-specific CD4+ T cells.

We observed the number of unique CD4+ clonotypes detected to consistently and markedly decrease within the first month post-transplant. This was, however, not specific to the patients undergoing combination cell therapy. It is consistent with analyses of the TCR repertoires of patients treated with a CKBMT involving myelosuppression and no Treg therapy,18 and indeed of any patients who received lymphodepletional induction therapy.26,27 Interestingly, we did not consistently observe a similar reduction in CD8+ clonotype numbers. In half of our case-group subjects and one control subject, the numbers actually increased, suggesting that sparing irradiation resulted in a less aggressive induction regimen and thus allowed for a more rapid recovery. We note that in the past we could not measure a drop in either CD4+ or CD8+ clonotype counts in transplant recipients receiving a reduced ATLG dose.23

Our JSD estimates, which compared each post-transplant repertoire to the respective pre-transplant baseline, point to only minor turnover occurring in all our study subjects, especially in CD8+ populations. They approach those of transplant patients who received reduced-dose ATLG induction,23 more so than those of irradiated CKBMT subjects.18 Also unlike irradiated subjects, the case patients analyzed here showed only a minor reduction in the number of alloreactive clonotypes detectable in the circulating repertoire and were, in that respect, not clearly distinguishable from the control group. Our data do not allow for discrimination of central vs peripheral clonal deletion, within the first six months after transplantation. Nevertheless, we find evidence of partial clonal deletion in the TCR repertoires of our CKBMT patients. Our results confirm that, in control recipients, the alloreactive load of the CD4+ repertoire tends to increase post-transplant, meaning that the total frequency of alloreactive cells grows more rapidly than that of randomly sampled clonotypes. This selective expansion of CD4+ T cells was dampened in patients undergoing combination cell therapy, who most often presented with reduced alloreactive loads after transplant. Therefore, the less aggressive Treg-based CKBMT protocol employed in this trial was sufficient to moderate the alloimmune response to the transplanted kidneys.

The high patient-to-patient variability observed in clonotype counts as well as JSD and post-transplant diversity estimates could reflect different responses to treatment and/or rates of recovery, which are thought to depend on age,28,29 as well as general immune dysfunction in chronically ill individuals.30,31 In general, variability between subjects was not unexpected, as even healthy individuals show significant and persistent differences in TCR repertoire diversity,32 likely reflecting their history of antigen exposure. Regardless, such high variability limited the statistical power of our analysis, given the relatively small sample size inherent to a phase I/IIa academic trial of this complexity. With this in mind, we included here all measurements and estimates computed for individual patients. Furthermore, we corrected for differences in the number of captured T cells by downsampling the sequenced repertoires, thereby ensuring the validity of the comparisons we made, and normalized our quantification of alloreactive load so as to control for differences in repertoire size and diversity. Nevertheless, our analysis remains explorative in nature, the small sample size limiting its predictive power. Another limitation of this study is the so-called bystander effect: it has been observed that highly proliferative, non-alloreactive T cell clones can unspecifically expand in the later stages of MLRs, which complicates the analysis of the alloreactive repertoire. While we could not collect enough cells to perform third-party stimulations and thereby reliably identify and exclude bystander clonotypes from our analysis, we addressed this limitation by requiring that clonotypes classified as alloreactive appeared in the proliferating fraction of MLRs at a frequency increased at least 5-fold, relative to baseline.33 Further, we verified that the observed between-group difference in fold-change of alloreactive load is robust against increases in this already stringent fold-expansion criterion.

The main strength of this study is the early and extensive characterization of the TCR repertoires of as many as six patients undergoing combination cell therapy. The sampling was dense and systematic, allowing a detailed description of repertoire turnover in the first six months post-transplant. We were able to separately analyze the Treg populations, often omitted from similar studies for their scarcity.18,23,33,34 Interestingly, we consistently detected in our case group a small increase in the diversity of Treg repertoires, as compared to those of control subjects. While the analysis of these repertoires is inevitably less reliable than that of more abundant T cell lineages, the data raises the possibility that the Treg infusions administered may have helped combat an ATG-driven loss of clonotypes. Given that the expansion of certain (donor-specific) Treg populations has been implicated in tolerance induction following CKBMT,35 this effect can be expected to add to the pro-tolerogenic potential of our protocol.

In conclusion, we show here that the circulating TCR repertoires of six kidney transplant recipients undergoing combination cell therapy were not narrowed or skewed, exhibiting turnover rates, post-transplant diversity and abundance of alloreactive clones comparable to those of conventional transplant patients. Furthermore, we observed a specific reduction in expansion of alloreactive clonotypes, which points to partial clonal deletion of donor-specific cells. This is an indication of tolerogenic modulation and thus invites further study into the potential of polyclonal Treg cell therapy in combination with donor bone marrow infusion to help achieve donor-specific tolerance in solid organ transplantation.

Contributors

AFD designed and performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. AH was involved in conception, study design, sample processing, data acquisition, and interpretation. MK was responsible for statistical data analysis. CA performed experiments. RRS, TL and MS were involved in conception and study design. KH, HSC, MM, AK and AMW participated in sample collection and processing. NW performed the Treg isolation and bone marrow harvesting. ME was responsible for Treg expansion. GB performed the kidney transplants. TW was responsible for conception, study design, and funding acquisition . RO was responsible for conception, study design, funding acquisition, supervision, and manuscript writing. AFD, AH and RO have accessed and verified the data. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the article and approved the submitted version.

Data sharing statement

Raw sequencing data and TCR clonotype tables are deposited in the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA), ID EGAD50000000302, and can be obtained for research purposes after approval by the Data Access Committee.

Declaration of interests

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the staff of our transplant center who supported the study with their expertise and were of tremendous administrative help in obtaining, labeling and biobanking samples. We thank the Core Facility Flow Cytometry and the Core Facility Genomics of the Medical University of Vienna, for providing the infrastructure for cell sorting and sequencing. Funding was obtained through the Vienna Science and Technology Fund (https://www.wwtf.at): WWTF Combination cell therapy for immunomodulation in kidney transplantation #LS18-031 and Genomics based immunologic risk stratification in kidney transplantation #10.47379/LS20081.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105239.

Appendix ASupplementary data

References

- 1.Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Lond Engl. 2020;395:709–733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30045-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hariharan S., Israni A.K., Danovitch G. Long-term survival after kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:729–743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2014530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strohmaier S., Wallisch C., Kammer M., et al. Survival benefit of first single-organ deceased donor kidney transplantation compared with long-term dialysis across ages in transplant-eligible patients with kidney failure. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.34971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wekerle T., Segev D., Lechler R., Oberbauer R. Strategies for long-term preservation of kidney graft function. Lancet. 2017;389:2152–2162. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayrdorfer M., Liefeldt L., Wu K., et al. Exploring the complexity of death-censored kidney allograft failure. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2021;32:1513–1526. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020081215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman J.R. Chronic Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity—lest we forget. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:693–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wyld M.L.R., De La Mata N.L., Masson P., O’Lone E., Kelly P.J., Webster A.C. Cardiac mortality in kidney transplant patients: a population-based cohort study 1988–2013 in Australia and New Zealand. Transplantation. 2021;105:413. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosales B.M., Mata N.D.L., Vajdic C.M., Kelly P.J., Wyburn K., Webster A.C. Cancer mortality in people receiving dialysis for kidney failure: an Australian and New Zealand cohort study, 1980-2013. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;80:449–461. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiebe C., Gibson I.W., Blydt-Hansen T.D., et al. Rates and determinants of progression to graft failure in kidney allograft recipients with de novo donor-specific antibody. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2921–2930. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawai T., Cosimi A.B., Spitzer T.R., et al. HLA-mismatched renal transplantation without maintenance immunosuppression. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:353–361. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scandling J.D., Busque S., Dejbakhsh-Jones S., et al. Tolerance and chimerism after renal and hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:362–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leventhal J., Abecassis M., Miller J., et al. Chimerism and tolerance without GVHD or engraftment syndrome in HLA-mismatched combined kidney and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahr B., Pilat N., Granofszky N., et al. Distinct roles for major and minor antigen barriers in chimerism-based tolerance under irradiation-free conditions. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:968–977. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilat N., Baranyi U., Klaus C., et al. Treg-therapy allows mixed chimerism and transplantation tolerance without cytoreductive conditioning. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:751–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pilat N., Mahr B., Unger L., et al. Incomplete clonal deletion as prerequisite for tissue-specific minor antigen tolerization. JCI Insight. 2016;1 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.85911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Podestà M.A., Sykes M. Chimerism-based tolerance to kidney allografts in humans: novel insights and future perspectives. Front Immunol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.791725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oberbauer R., Edinger M., Berlakovich G., et al. A prospective controlled trial to evaluate safety and efficacy of in vitro expanded recipient regulatory T cell therapy and tocilizumab together with donor bone marrow infusion in HLA-mismatched living donor kidney transplant recipients (Trex001) Front Med. 2021;7 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.634260. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2020.634260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris H., DeWolf S., Robins H., et al. Tracking donor-reactive T cells: evidence for clonal deletion in tolerant kidney transplant patients. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aschauer C., Jelencsics K., Hu K., et al. Next generation sequencing based assessment of the alloreactive T cell receptor repertoire in kidney transplant patients during rejection: a prospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:346. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1541-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaudhary N., Wesemann D.R. Analyzing immunoglobulin repertoires. Front Immunol. 2018;9:462. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill M.O. Diversity and evenness: a unifying notation and its consequences. Ecology. 1973;54:427–432. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aschauer C., Jelencsics K., Hu K., et al. Prospective tracking of donor-reactive T-cell clones in the circulation and rejecting human kidney allografts. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.750005. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.750005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aschauer C., Jelencsics K., Hu K., et al. Effects of reduced-dose anti-human T-lymphocyte globulin on overall and donor-specific T-cell repertoire reconstitution in sensitized kidney transplant recipients. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.843452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mallinckrodt C.H., Lane P.W., Schnell D., Peng Y., Mancuso J.P. Recommendations for the primary analysis of continuous endpoints in longitudinal clinical trials. Drug Inf J DIJ Drug Inf Assoc. 2008;42:303–319. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuler A. Mixed models for repeated measures should include time-by-covariate interactions to assure power gains and robustness against dropout bias relative to complete-case ANCOVA. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2022;56:145–154. doi: 10.1007/s43441-021-00348-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai L., Wang L., Chen H., et al. T cell repertoire following kidney transplantation revealed by high-throughput sequencing. Transpl Immunol. 2016;39:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong P., Cina D.P., Sherwood K.R., et al. Clinical application of immune repertoire sequencing in solid organ transplant. Front Immunol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1100479. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1100479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshida K., Cologne J.B., Cordova K., et al. Aging-related changes in human T-cell repertoire over 20 years delineated by deep sequencing of peripheral T-cell receptors. Exp Gerontol. 2017;96:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun X., Nguyen T., Achour A., et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals age-related changes in the T cell receptor repertoire of human T cell subsets. J Clin Invest. 2022;132 doi: 10.1172/JCI158122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winterberg P.D., Ford M.L. The effect of chronic kidney disease on T cell alloimmunity. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2017;22:22–28. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee G.H., Lee J.Y., Jang J., et al. Anti-thymocyte globulin-mediated immunosenescent alterations of T cells in kidney transplant patients. Clin Transl Immunol. 2022;11 doi: 10.1002/cti2.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu N.D., Bi H.S., Emerson R.O., et al. Longitudinal immunosequencing in healthy people reveals persistent T cell receptors rich in highly public receptors. BMC Immunol. 2019;20:19. doi: 10.1186/s12865-019-0300-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeWolf S., Grinshpun B., Savage T., et al. Quantifying size and diversity of the human T cell alloresponse. JCI Insight. 2018;3 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.121256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qi Q., Liu Y., Cheng Y., et al. Diversity and clonal selection in the human T-cell repertoire. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:13139–13144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409155111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savage T.M., Shonts B.A., Obradovic A., et al. Early expansion of donor-specific Tregs in tolerant kidney transplant recipients. JCI Insight. 2018;3 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.124086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.