Abstract

The ubiquitous existence of microplastics and nanoplastics raises concerns about their potential impact on the human reproductive system. Limited data exists on microplastics within the human reproductive system and their potential consequences on sperm quality. Our objectives were to quantify and characterize the prevalence and composition of microplastics within both canine and human testes and investigate potential associations with the sperm count, and weights of testis and epididymis. Using advanced sensitive pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, we quantified 12 types of microplastics within 47 canine and 23 human testes. Data on reproductive organ weights, and sperm count in dogs were collected. Statistical analyses, including descriptive analysis, correlational analysis, and multivariate linear regression analyses were applied to investigate the association of microplastics with reproductive functions. Our study revealed the presence of microplastics in all canine and human testes, with significant inter-individual variability. Mean total microplastic levels were 122.63 µg/g in dogs and 328.44 µg/g in humans. Both humans and canines exhibit relatively similar proportions of the major polymer types, with PE being dominant. Furthermore, a negative correlation between specific polymers such as PVC and PET and the normalized weight of the testis was observed. These findings highlight the pervasive presence of microplastics in the male reproductive system in both canine and human testes, with potential consequences on male fertility.

Keywords: polymers, particulates, pyrolysis GC/MS, testis, male reproductive, sperm count

The widespread presence of microplastics and nanoplastics in ecosystems and human bodies raises significant concerns about human health (Vethaak and Legler, 2021; Zhao et al., 2023; Zuri et al., 2023). Microplastics have been found to translocate across the blood-brain barrier in mouse models (Deng et al., 2017; Jin et al., 2022; Shan et al., 2022) and were detected in human blood and placentas (Garcia et al., 2024; Leslie et al., 2022). Most importantly, a small-scale study found microplastics in 5 human testes and 30 semen samples (Zhao et al., 2023), raising concerns about their potential accumulation in the male reproductive system. Animal studies reported that microplastics reduced sperm count and caused abnormalities, and hormone disruptions (Hou et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2022). Despite these advances, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding the internal levels of microplastics and their correlation with environmental plastic exposure and reproductive health impacts.

Traditional studies on human environmental exposure and its impact on fertility and the reproductive system face significant ethical challenges. Companion animals encounter a similar spectrum of anthropogenic environmental pollutants as humans. Analyzing their exposure and health outcomes as a window can help to understand environmentally triggered human diseases (Chen et al., 2022; Sumner et al., 2020). The similarity is underscored by the parallel decline in sperm count and motility observed in both species, positioning dogs as bioindicators for environmental exposure (Lea et al., 2016; Sumner et al., 2020). This study proposes a novel approach that addresses these challenges by utilizing tissues routinely discarded during sterilization in dogs. The goal of this study was to apply pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) to investigate the prevalence and types of microplastics within canine and human testis in male reproductive organs in real-world exposure. Furthermore, we assessed the correlation between the body-normalized testis and epididymis weight and sperm count in canine samples.

Materials and methods

Testis tissues (n = 47) from routine dog neuter surgeries were obtained from the consented donation of local veterinary clinics in Albuquerque, New Mexico, with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, 22-201245-T-HSC). Animal health and reproductive history were collected, including age, breed, body weight, time lived in the current zip code, food sources, reasons for neuter surgeries, and any known medical history. The weights of the testis and whole epididymis were recorded. Twenty-three human testis samples, ages ranging from 16 to 88, were obtained from the New Mexico Office of the Medical Investigator, with all samples anonymized. These samples were part of routinely collected specimens from 2016, which were available following a 7-year storage requirement after which the samples are usually discarded. A request for review of research involving the Office of the Medical Investigator resources was submitted for review and approval of the use of the tissue samples. For canine samples, epididymides were cut into thirds head, body, and tail, and weighed separately. Sperms were extracted from minced epididymal tail and densities counted on the hemocytometer. Digestion and isolation of microplastics and nanoplastics were conducted following previously published methods (Garcia et al., 2024) (see Supplementary Methods). The quantitative polymer mass data were normalized to the wet tissue weight. The data were log-transformed using the formula log10(X + 1). Statistical analyses, including distribution, ANOVA test, and multivariate linear regression analyses, were conducted using JMP Pro 17.

Results and discussion

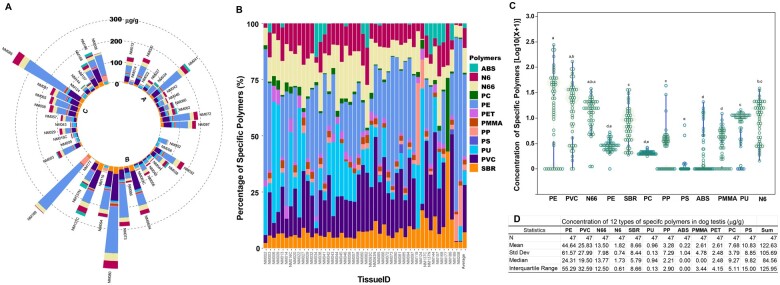

Using the Py-GC/MS, we analyzed the abundance of 12 types of microplastics in 47 dog testis samples. Figure 1A, a circular stacked bar chart illustrates the “microplastic spikes” at individual levels across 3 distinct age groups. Microplastics were detected in all testis samples with significant variation in levels, ranging from a low of 2.36 µg/g to a high of 485.77 µg/g. The composition of microplastics in each sample revealed a diversity of these contaminants, with PE and PVC being the dominant types (Figure 1B). Statistically significant differences in polymer levels were observed (ANOVA, p < .001, Figure 1C) with the highest mean concentration found in PE, followed by PVC, N66, N6, SBR, PU, PP, ABS, PMMA, PET, PC, and PS. The average concentration of all microplastics is 122.63 µg/g (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Quantitative analysis of microplastic contamination, distribution, and composition in canine testicular tissues. A circular bar chart displays the concentration of 12 types of microplastics in 47 dog testis samples (A) and the percentage composition of each dog testis (B), the abundance of specific polymers (C), and a statistical summary (D). Each segment represents a unique sample and the length of each bar indicates the quantity of individual microplastics measured. The color coding corresponds to the type of microplastic, as per the legend on the right. Each cluster (A, B, C) corresponds with age groups 2–10, 11–36, and >36 months, respectively. Data were transformed using log10(X + 1), and statistical comparison among the 12 types of polymers was conducted using 1-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey-Kramer HSD. Levels not connected by the same letter are significantly different at p ≤ .05.

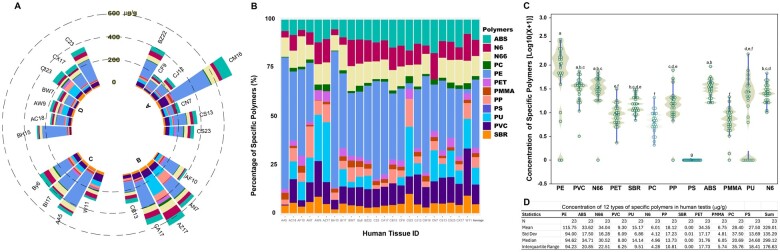

We further quantified polymers in 23 human testes as shown in Figure 2. Figure 2A indicates that microplastics were present in all samples and showed considerable variability, ranging from 161.22 to 695.94 µg/g. The stacked bar chart shows the composition of various polymers (Figure 2B), with PE being the most prevalent. The composition of these microplastics showed considerable diversity; samples 2, 7, 8, and 16 had little or no PE detected. Figure 2C shows the distribution of the data, and the embedded box plots indicate the median and interquartile ranges. The data highlight PE as the predominant polymer, followed by ABS, N66, PVC, PU, N6, PP, SBR, PET, PMMA, and PC (Figure 2D). The overall average concentration of microplastics was 328.44 µg/g.

Figure 2.

Quantitative analysis of microplastic concentration, distribution, and composition in human testicular tissues. The individual levels of 12 different types of microplastics were quantified in 23 human testicular tissue samples using Py-GC/MS analysis (A), the percentage composition of each testis (B), the abundance of specific polymers (C), and a statistical summary (D). Each radial segment represents a unique human sample ID, with the length of the bar indicating the level of a specific type of microplastic. Data were transformed using log10(X + 1) for normalization and statistical comparison among the 12 types of polymers was conducted using 1-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey-Kramer HSD. Levels not connected by the same letter are significantly different at p ≤ .05.

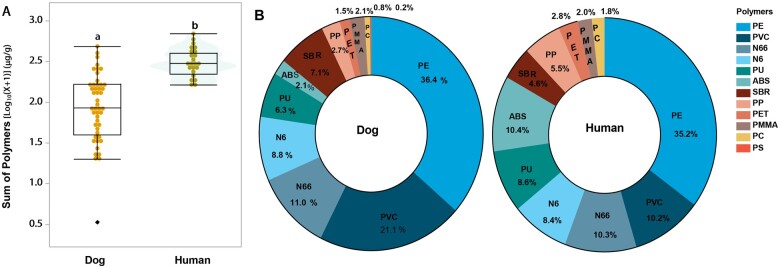

A comparative analysis of microplastics in canine and human testes (Figure 3) reveals that total microplastics were nearly 3 times greater in human testes than in canine tissues (p ≤ .001, Figure 3A). Also, significantly higher levels of PE, PVC, ABS, N66, N6, PP, SBR, PET, PMMA, and PC were observed in human testes compared with canine tissues (p ≤ .05). The proportion of specific polymers relative to the total microplastics in the tissues (Figure 3B) highlights both similarities and differences in composition between dogs and humans. PE was the most common polymer in both species, accounting for 36.4% in dogs and 35.2% in humans. Interestingly, human testes contained a higher proportion of ABS and a lower percentage of PVC compared with canine testes. These differences in composition and concentration between species offer insights into potential species-specific variations in environmental exposure and accumulation. The noteworthy individual variations of these polymers are larger in dogs than humans may stem from factors such as lifestyle, diet, and environmental conditions.

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of microplastic concentration and composition in canine and human testicular tissues. The box-and-whisker plot juxtaposed with a violin plot compares the sum of microplastic concentrations log-transformed with log10(X + 1) in canine and human testicular tissues (A). Panel (B) shows the 2 donut charts illustrating the relative composition of different microplastic types in the testicular tissues of dogs (left) and humans (right). Each section of the donut charts represents a specific type of microplastic, with the percentage indicating its proportion relative to the total microplastic content found in the tissues. Statistical comparison was conducted using 1-way ANOVA. Levels not connected by the same letter are significantly different at p ≤ .05.

The average concentration in human blood samples was 1.6 µg/ml, with maximum levels around 10–12 µg/ml (Leslie et al., 2022). Human placentas, at only 8 months old at delivery, exhibited microplastic concentrations ranging from 6.5 to 790 µg/g of tissue weight, with an average of 126.8 µg/g (Garcia et al., 2024). The 3-fold higher average concentration in the testes compared with the placentas implies the influence of both duration and potentially other factors on microplastic accumulation. Future research on the uptake, translocation, and accumulation of microplastics as well as mechanistic studies are critical as it remains possible that microplastic presence does not equate to functional effects in the reproductive system.

We initially presumed that age would significantly influence the overall levels of microplastics in both humans and dogs. However, the data revealed a more intricate relationship that defied a straightforward or linear interpretation. In dogs, the concentrations showed substantial variability without a clear age-related trend (Supplementary Figure 1A). In humans, variability was also substantial, with lower concentrations observed in individuals over 55 years (Supplementary Figure 1B). The absence of a distinct age-dependent accumulation of microplastics in human testes may be due to unique physiological and biological processes of spermatogenesis. The continuous renewal and release of sperm during spermatogenesis could help mitigate the buildup of microplastics over time. This hypothesis is supported by the presence of microplastic particles in human seminal fluid, suggesting a potential release mechanism during active spermatogenesis. Additionally, testes from public veterinary clinics showed higher levels of microplastics than those from private clinics (Supplementary Figure 1A), potentially reflecting the influence of socioeconomic differences on the living environments and lifestyles of the dogs. These findings collectively highlight the complex interplay of environmental, dietary, and lifestyle factors in the accumulation of microplastics within biological tissues. This underscores the critical need for further research to determine whether spermatogenesis acts as a route of “release,” and whether there is a causal connection between public versus private clinics that cause the differences noted. Also, there is a need to determine whether environmental, dietary, and lifestyle factors alter the presence, accumulation, and/or bioaccumulation of microplastics in biological tissues.

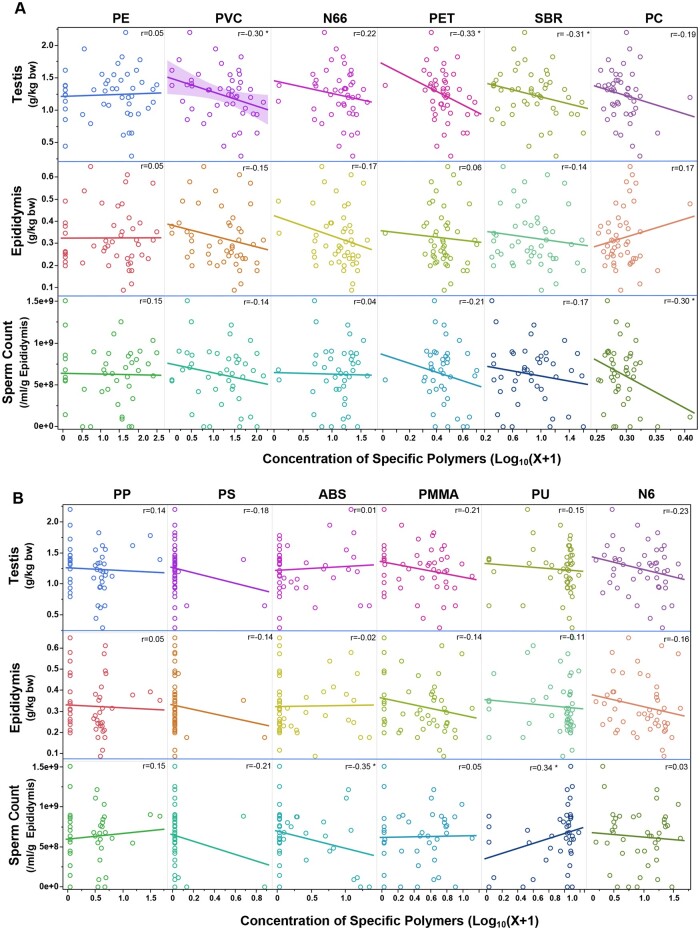

Furthermore, we conducted a correlation analysis between the log10-transformed concentrations of various microplastics and normalized reproductive parameters in dogs (Figure 4). These parameters include weights of testis and epididymis, and sperm count. Statistically significant negative correlations were observed with PVC, PET, and SBR for the body weight-adjusted testis weight. No statistically significant correlations were found for body weight-adjusted epididymis weight. A statistically significant negative correlation was observed between PC and ABS and sperm count. Multivariate linear regression analysis of the normalized testis weight, the age of the dog (in months), and various polymers showed that PVC, PET, PC, and PS were negatively associated with testis weight, whereas the dog’s age, N66, and ABS were positively associated (Supplementary Table 1). A negative association was found with PVC and a positive association with the dog’s age in the analysis of normalized epididymis weight. For sperm count, a negative association with the dog’s age and a positive association with PMMA were observed. The above results suggest a potential association between specific polymers and changes in testis weight or sperm counts. Generally, a decreased testis weight is indicative of reduced spermatogenesis (Creasy, 2003). Therefore, future study is needed to compare and determine the dose-response effects of these microplastics on spermatogenesis.

Figure 4.

Correlation analysis of microplastic concentration with body weight-corrected testis and epididymis weights, and sperm counts. This figure shows correlations between the log10(X + 1)-transformed concentrations of various microplastics and body weight-normalized reproductive parameters in dogs. These parameters include testis weight (g/kg body weight), epididymis weight (g/kg body weight), and sperm count (number of sperm per g cauda epididymis/ml). Each parameter is assessed against the concentration of different types of microplastics, which are distinguished by unique colors. An asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant correlation r coefficient at p ≤ .05.

The alarming temporal decline in male reproductive potentials, such as decreases in sperm count and quality, has been observed in men over the last several decades (Auger et al., 2022; Levine et al., 2023). There is also a rising incidence of testicular dysgenesis syndrome (TDS), a spectrum of reproductive disorders including hypospadias, cryptorchidism, male infertility, and testicular germ cell cancer (Skakkebaek et al., 2001). Environmental pollutants, such as phthalates, pesticides, and heavy metals, particularly those classified as endocrine disruptors (EDC), are potential contributors to TDS. These chemicals mimic natural hormones to interfere with the development of key testicular components of fetal Leydig and Sertoli cells (Sharpe and Skakkebaek, 2008). For example, bisphenol A (BPA), a ubiquitous EDC chemical in polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins, is detected in a vast majority of the population (Priyadarshini et al., 2023). BPA is found to interact with estrogen and androgen receptors and induces adverse effects on the reproductive system (Hu et al., 2023; Liang et al., 2017; Silva et al., 2023; Siracusa et al., 2018; Yin et al., 2020). Future studies are needed to examine if current levels of microplastics that exist in the reproductive system contribute to the decline of sperm count and quality.

Several limitations of this study warrant consideration. First, the human subjects in this study were unique, and typically did not experience a natural death. Therefore, the data should be considered indicative of what might be found in adult human testes but not necessarily representative of a broader population. Second, the combined approach of tissue digestion, ultracentrifugation, and Py-GC/MS is still being refined. Future research may reduce variability and clarify health outcome relationships with polymers more confidently. Lastly, we have not assessed the overall efficiency of our digestion process, and it is presumed that a fraction of smaller nanoparticles may have been lost during ultracentrifugation. It is important to acknowledge that this study was limited by a small sample size of only 47 dogs. Also, the observed associations between microplastic presence and sperm parameters do not imply causality. Future studies should include larger and more diverse samples to examine if current levels of microplastics in the reproductive system affect the male reproductive function. Moreover, it is crucial to expand the study of the human population to better understand human exposure and its potential adverse effects on the human reproductive system.

In conclusion, this study reveals the presence of microplastics in both human and canine testicular tissues, with an average abundance of total microplastics in human testes 3 times higher than that in canine testes. Both humans and canines exhibit relatively similar proportions of the major polymer types, predominated with PE. Negative correlations between canine testis weight and concentrations of PVC and PET were observed but did not imply causation. Our study highlights the need to determine the dose-response effects of these microplastics and to conduct mechanistic studies on the reproductive system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Special recognitions to the City of Albuquerque Councilwoman: Tammy Fiebelkorn, CABQ Animal Welfare Department: Dr Erin Clarke and team; Sandia Animal Clinic, and Kokopelli Animal Clinic.

Contributor Information

Chelin Jamie Hu, College of Nursing, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87106, USA.

Marcus A Garcia, College of Pharmacy, University of New Mexico, Akbuquerque, New Mexico 87106, USA.

Alexander Nihart, College of Pharmacy, University of New Mexico, Akbuquerque, New Mexico 87106, USA.

Rui Liu, College of Pharmacy, University of New Mexico, Akbuquerque, New Mexico 87106, USA.

Lei Yin, Reprotox Biotech, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131, USA.

Natalie Adolphi, Office of the Medical Investigator, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87106, USA.

Daniel F Gallego, Office of the Medical Investigator, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87106, USA.

Huining Kang, Department of Internal Medicine, Biostatistics Shared Resource of UNM Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87106, USA.

Matthew J Campen, College of Pharmacy, University of New Mexico, Akbuquerque, New Mexico 87106, USA.

Xiaozhong Yu, College of Nursing, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87106, USA.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Toxicological Sciences online.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

Microplastic concentrations were assessed in the Integrated Molecular Analysis Core of the UNM Center for Metals in Biology and Medicine (NIH P20 GM130422). Funding was also provided by the Academic Science Education and Research Training (K12 GM088021). This project was supported partially by pilot funding under NMINSPIRES-NIEHS (1P30ES032755).

References

- Auger J., Eustache F., Chevrier C., Jégou B. (2022). Spatiotemporal trends in human semen quality. Nat. Rev. Urol. 19, 597–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Cao S., Wen D., Geng Y., Duan X. (2022). Sentinel animals for monitoring the environmental lead exposure: Combination of traditional review and visualization analysis. Environ. Geochem. Health. 45, 561–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creasy D. M. (2003). Evaluation of testicular toxicology: A synopsis and discussion of the recommendations proposed by the Society of Toxicologic Pathology. Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. 68, 408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y., Zhang Y., Lemos B., Ren H. (2017). Tissue accumulation of microplastics in mice and biomarker responses suggest widespread health risks of exposure. Sci. Rep. 7, 46687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M. A. L. R., Nihart A., El Hayek E., Castillo E., Barrozo E. R., Suter M. A., Bleske B., Scott J., Forsythe K., Gonzalez-Estrella J., et al. (2024). Quantitation and identification of microplastics accumulation in human placental specimens using pyrolysis gas chromatography mass spectrometry. Toxicol. Sci. 199, 81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou B., Wang F., Liu T., Wang Z. (2021). Reproductive toxicity of polystyrene microplastics: In vivo experimental study on testicular toxicity in mice. J. Hazard. Mater. 405, 124028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C., Hsiao Z. H., Yin L., Yu X. (2023). The role of small GTPases in bisphenol AF-induced multinucleation in comparison with dibutyl phthalate in the male germ cells. Toxicol. Sci. 192, 43–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H., Yang C., Jiang C., Li L., Pan M., Li D., Han X., Ding J. (2022). Evaluation of neurotoxicity in BALB/c mice following chronic exposure to polystyrene microplastics. Environ. Health Perspect. 130, 107002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea R. G., Byers A. S., Sumner R. N., Rhind S. M., Zhang Z., Freeman S. L., Moxon R., Richardson H. M., Green M., Craigon J., et al. (2016). Environmental chemicals impact dog semen quality in vitro and may be associated with a temporal decline in sperm motility and increased cryptorchidism. Sci. Rep. 6, 33267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie H. A., van Velzen M. J. M., Brandsma S. H., Vethaak A. D., Garcia-Vallejo J. J., Lamoree M. H. (2022). Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. Environ. Int. 163, 107199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine H., Jorgensen N., Martino-Andrade A., Mendiola J., Weksler-Derri D., Jolles M., Pinotti R., Swan S. H. (2023). Temporal trends in sperm count: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of samples collected globally in the 20th and 21st centuries. Hum. Reprod. Update. 29, 157–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S., Yin L., Shengyang Yu K., Hofmann M. C., Yu X. (2017). High-content analysis provides mechanistic insights into the testicular toxicity of bisphenol A and selected analogues in mouse spermatogonial cells. Toxicol. Sci. 155, 43–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priyadarshini E., Parambil A. M., Rajamani P., Ponnusamy V. K., Chen Y. H. (2023). Exposure, toxicological mechanism of endocrine disrupting compounds and future direction of identification using nano-architectonics. Environ. Res. 225, 115577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan S., Zhang Y., Zhao H., Zeng T., Zhao X. (2022). Polystyrene nanoplastics penetrate across the blood-brain barrier and induce activation of microglia in the brain of mice. Chemosphere 298, 134261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe R. M., Skakkebaek N. E. (2008). Testicular dysgenesis syndrome: Mechanistic insights and potential new downstream effects. Fertil. Steril. 89, e33–e38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva A. B. P., Carreiro F., Ramos F., Sanches-Silva A. (2023). The role of endocrine disruptors in female infertility. Mol. Biol. Rep. 50, 7069–7088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siracusa J. S., Yin L., Measel E., Liang S., Yu X. (2018). Effects of bisphenol A and its analogs on reproductive health: A mini review. Reprod. Toxicol. 79, 96–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skakkebaek N. E., Rajpert-De Meyts E., Main K. M. (2001). Testicular dysgenesis syndrome: An increasingly common developmental disorder with environmental aspects. Hum. Reprod. 16, 972–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner R. N., Harris I. T., Van der Mescht M., Byers A., England G. C. W., Lea R. G. (2020). The dog as a sentinel species for environmental effects on human fertility. Reproduction 159, R265–R276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vethaak A. D., Legler J. (2021). Microplastics and human health. Science 371, 672–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z., Wang Y., Wang S., Xie J., Han Q., Chen M. (2022). Comparing the effects of polystyrene microplastics exposure on reproduction and fertility in male and female mice. Toxicology 465, 153059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L., Siracusa J. S., Measel E., Guan X., Edenfield C., Liang S., Yu X. (2020). High-content image-based single-cell phenotypic analysis for the testicular toxicity prediction induced by bisphenol A and its analogs bisphenol S, bisphenol AF, and tetrabromobisphenol A in a three-dimensional testicular cell co-culture model. Toxicol. Sci. 173, 313–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q., Zhu L., Weng J., Jin Z., Cao Y., Jiang H., Zhang Z. (2023). Detection and characterization of microplastics in the human testis and semen. Sci. Total Environ. 877, 162713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuri G., Karanasiou A., Lacorte S. (2023). Human biomonitoring of microplastics and health implications: A review. Environ. Res. 237, 116966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.