Abstract

Hemangiomas are considered slow growing benign neoplasms. Primary thyroid hemangiomas are uncommon and may pose difficulty in diagnosis due to absence of distinctive imaging characteristics and related clinical symptoms. It is crucial to precisely identify these lesions to aid in implementing nonsurgical treatment plans rather than resorting to surgical procedures in certain cases. In this report we present a case of a 76-year-old female who presented with painless, rapid, and sudden notice of right-side neck swelling over a 1-day duration. Her radiological examinations raised the concern of a vascular lesion that was emoblized endovascularly. Then, it was surgically removed, which was eventually determined to be primary thyroid hemangioma. In addition, we present a literature review of previously published cases and discuss tumor pathophysiology, clinical presentations, radiology features, and differential diagnosis.

Keywords: hemangioma, neoplasm, malformation, thyroid, vascular

Introduction

Hemangiomas are benign neoplasms composed of pathological vascular proliferation. Most originate in the head and neck region, mostly oral cavity, skin, and deep visceral organs such as the liver. Primary thyroid hemangiomas may arise due to minor or major trauma to the neck, including fine needle aspiration (FNA) or developmental abnormalities. Hemangiomas arising de novo in thyroid gland without previous history of trauma are uncommon. A thorough analysis of literature publications until the year 2024 reveals less than 40 documented instances [1–7]. According to most literature, primary thyroid hemangiomas are commonly identified in patients with slowly developed neck swelling as the primary manifestation with no concurrent symptoms. Larger lesions can compress adjacent airway or esophagus, resulting in symptoms such as dysphagia, voice changes, and dyspnea [1, 2]. Table 1 shows that most of the reported cases exhibited a gradual increase in the size of the mass over the course of several months to years. However, our case is the first to demonstrate a sudden and significant growth within a single-day duration. Accurately identifying these lesions is crucial to promptly initiating non-surgical treatment, eliminating the need for surgery in certain situations.

Table 1.

Summary of reported cases of primary thyroid hemangioma (n = 39).

| Authors, year | Age | Sex | Size in maximum (cm) | Duration before surgery | Tumor site | Tumor histology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pickleman et al. (1975) [3] | 56 | Male | 7.5 | Several months | Left | Cavernous |

| 2 | Queiroz et al. (1978) [3] | 29 | Female | 6.5 | NA | Right | Cavernous |

| 3 | Queiroz L et al. (1978 [3] | 33 | Male | 9 | NA | Right | Cavernous |

| 4 | Queiroz L et al. (1978 [3] | 54 | Male | 9 | NA | Right | Cavernous |

| 5 | Hernández JC et al. (1979 [3] | 55 | Female | 2 | NA | Right | Capillary |

| 6 | Ismaĭlov A et al. (1981 [3] | 55 | Male | 10 | NA | Right | Cavernous |

| 7 | Okuno et al. (1981 [2] | 7 | Male | NA | NA | Diffuse | Capillary |

| 8 | Ishida T et al. (1982 [3] | 46 | Male | 14 | 20 years | Right | Cavernous |

| 9 | Ishida T et al. (1982 [3] | 4 | Male | 9 | 1 year | Isthmus | Cavernous |

| 10 | Ishida T et al. (1982 [3] | 57 | Female | 8 | 20 years | Right | Cavernous |

| 11 | Yokota T et al. (1991 [3] | 64 | Female | 7.2 | 9 months | Right | Cavernous |

| 12 | Pendse A et al. (1998 [3] | 53 | Male | 6 | NA | Right | Cavernous |

| 13 | Kumar et al. (2000) [3] | 53 | Male | 4 | Incidentally during radionuclide ventriculography | Right | NA |

| 14 | Rios et al. (2001) [3] | 63 | Female | 5 | 2 months | Left | Cavernous |

| 15 | Rios et al. (2001) [3] | 48 | Female | 5 | 1 month | Left | Cavernous |

| 16 | Kumamoto et al. (2005) [3] | 56 | Female | 7 | Not mentioned | Right | Cavernous |

| 17 | Senthilvel et al. (2005) [3] | 24 | Male | 6 | 3 months | Right | NA |

| 18 | Kano et al. (2005) [3] | 21 | Male | 5.5 | Not mentioned | Right | Cavernous |

| 19 | Lee et al. (2007) [3] | 66 | Male | 17 | 2 years | Left | Cavernous |

| 20 | Ciralik et al. (2008) [3] | 64 | Male | 7 | 2 years | Right | Cavernous |

| 21 | Datta et al. (2008) [3] | 25 | Male | 4.9 | 16 years | Left | Cavernous |

| 22 | Sakai et al. (2009) [3] | 71 | Female | 5.2 | 1 year | Left | Cavernous |

| 23 | Michalopoulos et al. (2010) [3] | 78 | Male | 4 | 6 months | Right | Cavernous |

| 24 | Maciel et al. (2011) [3] | 80 | Female | 22 | 40 years | Left | Cavernous |

| 25 | Gutzeit et al. (2011) [3] | 84 | Female | NA | Not mentioned | Left | Cavernous |

| 26 | Jacobson et al. (2014) [2] | 2 months | Female | 3.7 | From first few weeks of life | Right | NA |

| 27 | Dasgupta et al. (2014) [3] | 38 | Male | 6 | 1 year | Left | Cavernous |

| 28 | Karanis et al. (2015) [1] | 45 | Female | 6 | 6 months | Right | Cavernous |

| 29 | Miao et al. (2017) [3] | 48 | Male | 4 | 20 years | Right | Cavernous |

| 30 | Quanjiang et al. (2019) [2] | 12 | Female | 2 | NA | Right | NA |

| 31 | Liang et al. (2020) [2] | 2 months | Female | 3 | 20 days | Right and left | Capillary |

| 32 | Yang et al. (2020) [3] | 24 | Female | 3.6 | 2 months | Left | NA |

| 33 | Bains et al. (2020) [3] | 77 | Female | 6 | 1 year | Right | Cavernous |

| 34 | Masuom et al. (2021) [3] | 63 | Male | 7 | 2 months | Right | Cavernous |

| 35 | Cristel et al. (2021) [4] | 56 | Female | 4 | Not mentioned | Right | Not mentioned |

| 36 | Díaz-García et al. (2022) [6] | 51 | Female | 4.5 | Radiology discovered incidentally | Right | Cavernous |

| 37 | Mukhuba et al. (2022) [5] | 51 | Male | 7.5 | 5 years | Left | Cavernous |

| 38 | Seuferling et al. (2023) [7] | 62 | Female | 3.1 | 4 years | Right | Thick wall blood vessels |

| 39 | Our case | 76 | Female | 7.5 | 1 day | Right | Thick wall blood vessels |

Case presentation

This case study describes a 76-year-old female with a history of type 2 diabetes and hypertension for fifteen years, controlled by her medication. She was swimming when she noted a sudden swelling in her neck. She presented to the emergency department of our hospital with right neck swelling for one-day duration. Physical examination shows a vitally stable patient with a localized neck mass not movable with swallowing and not associated with compressive symptoms. Computed tomography (CT) scan showed significant enlargement of the right thyroid lobe with heterogeneous predominantly hyperdense mass with mass effect on the airway with leftward deviation of the trachea (Fig. 1). Pre-operative CT Angiography showed active extravasation (Fig. 2). Also, there is a suspected right thyroid artery arching over the hematoma. The appearance of the artery raised the possibility of this artery being the cause of the hematoma. Then, a diagnostic angiogram was performed, which showed a dilated, ectatic-looking superior thyroid artery with flow into the hematoma, confirming the source of the hematoma. The patient successfully underwent angioembolization and hematoma evacuation without complications. During the procedure, an unexpectedly large solid component resembling thyroid tissue and a sac surrounding the hematoma were found. The patient was admitted to the Surgical Intensive Care Unit for post-operative monitoring and to prevent potential airway obstruction. The resected specimen was sent for further evaluation by pathology. Gross examination shows large dark brown hemorrhagic mass with thyroid tissue identified measuring 7.5 cm × 0.5 cm. Histopathology examination of the specimen revealed thyroid tissue with extensive hemorrhage and irregular dilated vascular spaces, as well as capillary-like vessels present in thyroid parenchymal tissue. Few thick-walled blood vessels were seen. These vascular channels are lined by bland endothelial cells (Fig. 3A, B). No cellular atypia, mitosis or solid growth pattern was observed. The vascular lining is diffusely positive for CD34, CD31, D2–40, and FLI1 (Fig. 3C, D). Given the above features of histopathology and immunohistochemistry studies, the diagnosis was compatible with primary thyroid hemangioma. Five months post-surgical resection, the patient’s follow-up indicates that she is in good health with no neck swelling, hoarseness of voice, or difficulty tolerating a regular diet. Her wound has healed without any signs of infection.

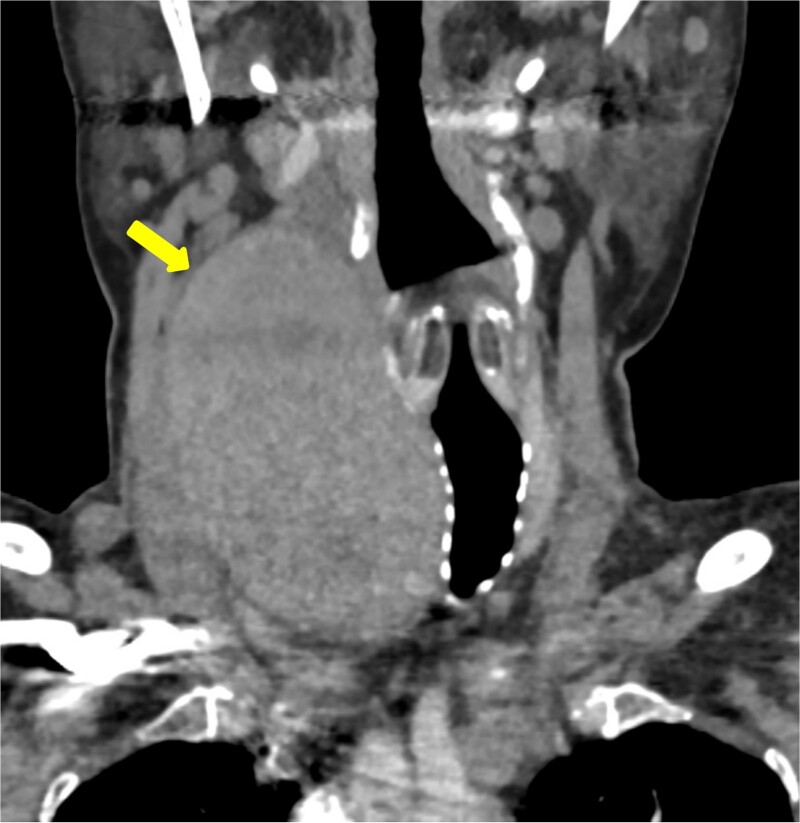

Figure 1.

Coronal imaging of the unenhanced CT shows a large right thyroid lobe heterogeneous mass measuring 9.2 cm × 5.2 cm × 5.5 cm with mass effect on the airway and tracheal displacement to the left.

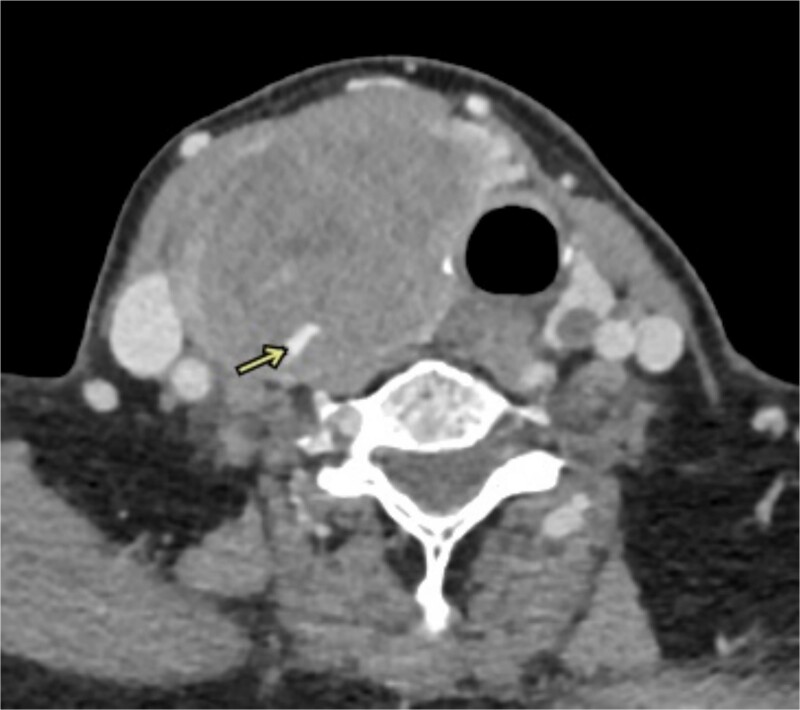

Figure 2.

CT angiography shows active extravasations along the posterior aspect of the right thyroid lobe mass.

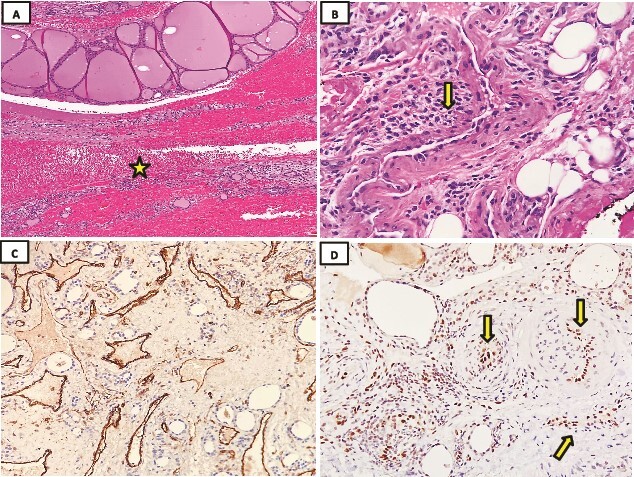

Figure 3.

Histopathology examination was done using hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E). (A) Microscopic evaluation of the lesion consisted of a rim of thyroid tissue filled with a central hemorrhagic zone (star) (H&E; 4x). (B) The lesion comprises a compact growth of thick wall blood vessels lined by plump endothelial cells (arrow) (H&E; 10x). (C) Immunohistochemical staining showed strongly positive CD31 in endothelial cells (40x). (D) Strongly nuclear positive endothelial cells for FLI1 (arrow) (40x).

Discussion

Hemangiomas are benign growths resulting from excessive vascular endothelial cell proliferation or malformations. Frequently observed in children and typically present from birth. It is worth noting that hemangiomas tend to be more prevalent in the skin, subcutaneous tissue, soft tissue, and liver. Histologically, it can be categorized into various types, such as synovial, cavernous, capillary, anastomosing, sclerosing, or arteriovenous. Vascular deformities can be categorized into two main groups; vasoproliferative neoplasms, also known as hemangiomas, which are characterized by rapid growth and proliferation of endothelial cells. In contrast, vascular malformations (VMs) are structural anomalies that affect the development of veins, lymphatics, capillaries, and arterioles. Unlike vasoproliferative neoplasms, VMs do not exhibit rapid growth and proliferation of endothelial cells, but rather grow in proportion to the child’s overall development [8]. Thyroid hemangioma is often seen because of a previous history of neck surgeries or post-FNA complications. The occurrence of primary hemangiomas in the thyroid gland is infrequent. Our literature review extended until 2024, and we came across 39 reported cases, including the case we presented. In 1975, Pickleman et al. reported the initial instance of thyroid hemangioma [3]. The exact pathogenesis is poorly understood due to a limited number of reported instances. However, according to certain theories the presence of these conditions could be linked to atypical development caused by the inability of the angioblastic mesenchyma to construct canals [5]. Table 1 summarizes all reported cases, demonstrating a slight female predominance (20 female, and 19 male). Patients’ ages ranged between 2 months and 84 years, with the right-side lesion being more dominant (66%), left side (30%), and isthmus (2%). Most were of cavernous subtype (71%), while capillary was (3%). Tumor size ranges from 2 to 22 cm. Most patients presented primarily with gradually progressing neck mass with no associated symptoms. Other reported symptoms in previous studies are neck discomfort, dysphagia, and hoarseness of voice. Other issues, such as swallowing and breathing difficulties, tracheal deviation, and paralysis of the vocal cord have been documented [3, 5, 7]. The duration for which these symptoms persisted varied, ranging from one month to as long as 40 years. Some were also discovered as chance findings during radiology examinations conducted for unrelated reasons. Our case is characterized by an abrupt onset that occurred within a one-day notice without a previous history of trauma or FNA. Perioperative punctures by FNA pose a significant risk of bleeding and have low cytology diagnostic yield. Ultrasound imaging findings are the first modality to assess thyroid mass. Thyroid hemangiomas on ultrasound can vary depending on whether there is a hemorrhage or not. Classically, they are anechoic masses with internal septations and posterior enhancement. Hemorrhage would be seen as internal hyperechogenicity at a fluid–fluid level. Usually, it is a compressible mass. Some flow can be seen in color Doppler studies. It enhances on contrast-enhanced ultrasound with a classic slow in a slow-out pattern. On the unenhanced CT scan, if there is no hemorrhage, they appear a hypodense mass. Post-contrast injection demonstrates gradual enhancement, less than the background thyroid tissue. Radiologically differential diagnosis would include thyroid cystic masses such as simple thyroid cysts, as well as cystic tumors such as cystic papillary thyroid carcinoma, or undifferentiated vascular lesions such as hemangiosarcoma. Surgical removal by hemithyroidectomy or total thyroidectomy is considered the preferred method of treatment for thyroid hemangioma. Histopathological examination is typically necessary in nearly all patients and is considered the gold standard for final diagnosis. Microscopic evaluation of hemangioma can show demarcated proliferation of variably sized dilated and thin-walled blood vessels lined by a single layer of flat endothelium. No cytologic atypia or mitosis is seen in these tumors. These vascular spaces can be separated by fibrous septa containing small vessels. Thrombi, calcification, and stromal hyalinization can be seen. Strong and uniform positive staining in endothelial cells can be seen with vascular markers such as CD31, CD34, ERG, FLI1, and Factor VIII. The overall prognosis of thyroid hemangioma after resection is good.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of primary thyroid hemangioma presented with abrupt sudden onset over one-day duration. When a well-defined capsulated mass is observed on radiology image, it is important to consider the possibility of primary thyroid hemangioma as well as other tumors while making a differential diagnosis. Histopathology tissue resection examination is regarded as the gold standard for final diagnosis. Surgical resection is indicated when a tumor causes symptoms of adjacent organ compression. The overall prognosis after surgery is good.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Contributor Information

Haneen Al-Maghrabi, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Jeddah 23433, Saudi Arabia.

Hosam Alardati, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Jeddah 23433, Saudi Arabia.

Ghouth Waggass, Department of Radiology, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Jeddah 23433, Saudi Arabia.

Mohammed Aref, Neurosurgery, Neurosciences Department, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Jeddah 23433, Saudi Arabia.

John Heaphy, Otolaryngology, Department of Surgery, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Jeddah 23433, Saudi Arabia.

References

- 1. Karanis MIE, Atay A, Kucukosmanoglu I, et al. Primary cavernous hemangioma of the thyroid. Int J Case Rep Images 2015;6:352–5. 10.5348/ijcri-201560-CR-10521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liang Y, Pu R, Huang X, et al. Airway obstruction as primary manifestation of infantile thyroid hemangioma. Ita J Ped 2020;46:1–5. 10.1186/s13052-020-00904-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Masuom SHF, Amirian-Far A, Rezaei R. Primary thyroid hemangioma: a case report and literature review. Kardiochirurgia i Torakochirurgia Polska/Polish J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2021;18:186–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cristel RT, McGinn L, Kumar S, et al. Thyroid hemangioma and concurrent papillary thyroid carcinoma. Otolaryngol Case Rep 2021;21:100371. 10.1016/j.xocr.2021.100371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mukhuba LN, Bhuiyan MMZU. Primary thyroid cavernous haemangioma: report of a case with review 3 years after operation. South Afr Med J 2022;112:936–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Díaz-García A, Caballero-Rodríguez E, García-Martínez R, et al. Primary cavernous hemangioma of the thyroid mimicking an ectopic cervical thymoma. J Surg Case Rep 2022;2022:rjac411. 10.1093/jscr/rjac411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seuferling J, Diaz A, Futran N, et al. Primary thyroid hemangioma, a rare diagnosis in a patient with a painless neck mass. Radiol Case Rep 2023;18:519–23. 10.1016/j.radcr.2022.10.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hasan S, Khan A, Banerjee A, et al. Infantile hemangioma of the upper lip: report of a rare case with a brief review of literature. Cureus 2023;15:e42556. 10.7759/cureus.42556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]