Abstract

Purpose

To assess the clinical efficacy of arthroscopic treatment for posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) tibial avulsion fractures using high-intensity suture binding combined with button plate suspension fixation.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed clinical data from 32 patients with PCL tibial avulsion fractures treated at our hospital from July 2020 to August 2023. We recorded operation time, intraoperative and postoperative complications, and used imaging to assess fracture reduction and healing. Pain and knee function were evaluated using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), range of knee motion, Lysholm score, and International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score.

Study Design

Case series; Level of evidence, 4.

Results

All patients were followed for 6 to 18 months, averaging 13.6 months. All incisions healed successfully without postoperative complications. X-rays taken on the first postoperative day showed satisfactory fracture reduction. Three-month post-surgery imaging confirmed healed fractures and no internal fixation failures. At the final follow-up, knee function was well recovered, with only one patient exhibiting a positive posterior drawer test of degree I. Furthermore, the mean VAS score was 0. 5 (range 0.0 to 1.0), active knee extension was 2. 2° (range 0.0 to 5.0), and active knee flexion was 137.7° (range 130.0 to 145.0). The mean Lysholm score was 91.5(range 89.3 to 94.0), and the IKDC score averaged 83.8 ± 3.7, and these outcomes showed statistically significant improvement from preoperative levels (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Arthroscopic high-intensity suture binding combined with button plate suspension fixation for PCL tibial avulsion fractures offers several benefits: it is minimally invasive, results in less postoperative pain, enables earlier functional exercise, and provides satisfactory clinical outcomes with fewer complications.

Keywords: Arthroscopy, Avulsion fractures, Posterior cruciate ligament, Suture fixation, Button plate fixation

Background

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injuries typically result from high-energy trauma to the proximal tibia, often occurring during traffic accidents or contact sports [1, 2]. A PCL tibial avulsion fracture, a special type of PCL injury, is relatively common in clinical settings. Recently, arthroscopic techniques have become prevalent for treating patients with PCL tibial avulsion fractures. Current literature suggests that suture fixation [3–5] and button plate fixation [6–8] are the most commonly employed arthroscopic methods for these injuries. However, compared to traditional open reduction and internal fixation, arthroscopic approaches have been criticized for less reliable fixation, potentially leading to postoperative displacement of the fracture block.

The author developed a dual fixation method: initially, a high-strength suture was looped through the edge of the PCL’s tibial attachment and wrapped around the ligament to form a cuff. Subsequently, a button plate was positioned directly over the high-strength suture above the fracture block. The surgeon then created an anterior-to-posterior tibial tunnel, through which the ends of the high-intensity suture were extracted. Finally, an anchor was placed adjacent to the tibial tubercle, and its suture was tied and secured together with the high-intensity suture, forming a “high-intensity suture binding combined with button plate suspension fixation.” This technique not only secured the fracture block more effectively and reliably, facilitating early postoperative rehabilitation but also enhanced the restoration of PCL tension, reducing subsequent laxity.

This study retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of 32 patients treated with this method at Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital of Jiangsu Province from July 2020 to August 2023. The objective was to evaluate the clinical efficacy of arthroscopic management of PCL tibial avulsion fractures using this dual fixation approach.

Materials and methods

Inclusive and exclusive criteria

Inclusion Criteria: (1) Preoperative imaging and intraoperative findings confirming PCL tibial avulsion fracture, which may present a U-shaped appearance on plain anteroposterior radiographs [9]; (2) Classification according to the Griffith scale (the modified Meyers and McKeever scale) as type II or III [10]; (3) Acute injury, defined as occurring within 3 weeks of presentation; (4) Post-anesthesia physical examination indicating a degree II (≥ 5 mm) or higher posterior tibial instability based on the Harner evaluation criteria [11]; (5) A minimum postoperative follow-up of six months and availability of complete clinical data.

Exclusion Criteria: (1) Patients with multiple ligament injuries of the knee, with the PCL avulsion fracture being only one component; (2) Combined tibial plateau fracture or other fractures within the knee joint; (3) Patients under 18 years of age; (4) Evidence of systemic or localized infection during the preoperative evaluation; (5) Severe internal medical conditions rendering the patient unable to tolerate surgery.

Characteristics of the study group

A total of 32 patients with PCL tibial avulsion fractures who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled, comprising 18 males and 14 females. The age range of the patients was 28 to 77 years, with a mean age of 47.2 ± 12. 1 years. Among these patients, 13 had left knee injuries and 19 had right knee injuries; 22 cases were classified as Type II and 10 as Type III according to the Griffith classification. The interval between injury and surgery ranged from 2 to 12 days, with an average of 4.79 ± 2.80 days. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital of Jiangsu Province (2021js014), and all patients provided signed informed consent forms prior to surgery.

Surgical technique

The procedure was performed under intravertebral or general anesthesia. Patients were positioned supine with a tourniquet inflated on the proximal thigh. Initially, anteromedial (AM) and anterolateral (AL) portals were established. The surgeon then cleared the joint cavity and examined the intra-articular structures. If a meniscus injury was present, it was addressed with reconstruction or suturing prior to further interventions.

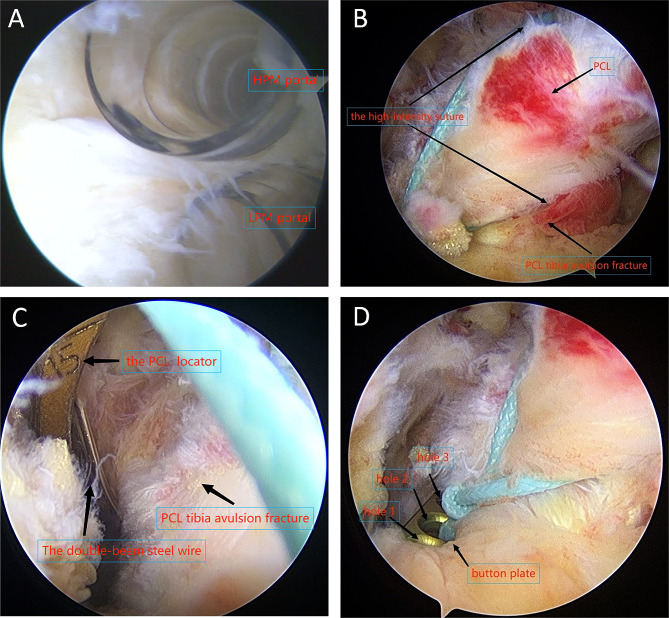

Subsequently, the knee was flexed to 90 degrees, and low posteromedial (LPM) and high posteromedial (HPM) portals were established (Fig. 1A), each equipped with a cannula. The surgeon used a planer to clear the posterior synovium and mediastinum of the knee, exposing the avulsion fractures. Often, the fracture block was encased by intact PCL fibers and surrounding synovial joint capsule, presenting as a “package” (Fig. 1B). At this stage, it was unnecessary to further clean or expose the fracture block. Instead, the probe was used to gently manipulate and reposition it to achieve alignment. In cases of severe fractures with soft tissue embedded in the lower bone groove, the fracture block was opened, the soft tissue was removed, the wound was debrided, and the fracture was reduced.

Fig. 1.

(A) Establish a low posteromedial (LPM) and a high posteromedial (HPM) portal under arthroscopy. (B) The fracture block was enveloped by surrounding soft tissue, forming a “package.” A high-intensity suture was looped around the tibial-sided root of the PCL. (C) Insert the PCL locator via the anterior medial approach. Introduce a double-beam steel wire through the tibial tunnel. (D) Display the button plate (holes1, 2, and 3). This illustrates the dual fixation method of “high-intensity suture binding combined with button plate suspension fixation.”

Arthroscopy was performed through the anterolateral approach for observation. The surgeon employed a straight suture hook loaded with PDS thread to puncture both the inner and outer sides of the PCL’s tibial insertion point, placing a PDS thread on each side. Subsequently, two PDS threads were used to introduce a high-strength suture via the LPM portal. The free ends of this high-strength suture were crossed and looped half a circle around the tibial base of the PCL (Fig. 1B), and then extracted from the LPM portal. This maneuver created a loop with the high-strength suture, which was then secured above the PCL tibial avulsion fractures.

Arthroscopic observation was conducted using a low posterior internal approach, and the PCL Reconstruction locator (Nephew, USA) was inserted via the anterior medial approach (Fig. 1C). The locator’s inner port was positioned directly beneath the PCL tibia avulsion fractures. A 2.0 cm incision was made on the medial side of the tibial tuberosity, where the locator was positioned. A tibial bone canal was then created following the path of the PCL Reconstruction locator. The double-strand steel wire was threaded through the tibial tunnel (Fig. 1C), and exited through the LPM portal, serving as an internal guide. A button plate (Smith & Nephew, USA) was selected for loop removal. The operator inserted a line into the first hole (defined as hole 1 in Fig. 1D) to serve as an external traction line. The free ends of the high-intensity suture were threaded through the middle two holes of the button plate (defined as holes 2 and 3 in Fig. 1D), routed through the steel wire, and then knotted. The steel wire was withdrawn, pulling the high-intensity suture through the external port of the tibial bone canal. The operator then pulled the external traction line and the high-intensity suture, using a probe to adjust the position of the button plate to align with the fracture surface and secure it laterally above the fracture block. An anchor was placed near the tibial bone canal. With the knee flexed to 90°, the high-intensity suture was tightened as much as possible, tied, and secured with the anchor suture, establishing a dual fixation mode of “high-intensity suture binding combined with button plate suspension fixation” (Fig. 1D).

At this stage, under arthroscopic guidance, the high-intensity suture repositioned the PCL, the button plate approximated the fracture block, and the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments resumed their normal shape and tension, converting the posterior drawer test or step sign to negative. The joint cavity was irrigated, and the incision was sutured closed. The specific surgical procedure is depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

(A) The surgeon employs a straight suture hook equipped with PDS thread (purple) to puncture the inner and outer sides of the tibial insertion point of the PCL, then introduces a high-strength suture from the low posterior medial approach. (B) Extract the two free ends of the high-strength suture through the front inner approach. (C) Cross and wrap the two free ends of the high-strength suture half a circle around the base of the PCL tibial insertion point, pulling them out via the low posterior medial approach, forming a loop tied above the fracture block. (D) Create a 2.0 cm incision on the medial side of the tibial tuberosity and use an electric drill to form a tibial bone passage from front to back, exiting just below the PCL tibial avulsion fracture site. (E) Introduce double bundle steel wire (yellow) through the tibial tunnel, exiting through a low posterior medial approach as an internal guide wire. Place a wire (brown) in a hole adjacent to the button steel plate as an external traction wire. Thread the two free ends (blue) of the high-strength wire through the middle two holes of the button steel plate clockwise, pass through the steel wire (yellow), and tie a knot. (F) Withdraw the steel wire and lead the high-strength wire (blue) out from the external opening of the tibial tunnel. The surgeon pulls the external traction wire (brown) and high-strength wire (blue) to press the button steel plate against the fracture surface and secure it horizontally above the fracture block. Insert an anchor nail near the tibial bone canal, tie, and secure the high-strength thread

Post-operative management

Following surgery, the knee joint was immobilized using a hinged brace. On the first post-operative day, patients were encouraged to initiate isometric quadriceps femoris contractions, ankle pump movements, and straight leg raises as soon as possible. However, the knee was maintained in an extended position while at rest. During the first 4 weeks post-surgery, knee flexion exercises were conducted under the protection of the brace. The target was to achieve 90° of flexion 2 weeks post-surgery, 120 ° at 4 weeks, and full range by 6 weeks. From 4 to 8 weeks post-surgery, patients gradually began walking with the aid of crutches, still under brace protection. The brace was used for 3 months. Free movement of the knee joint resumed after 3 months, and high-intensity sports were permitted after 6 months.

Postoperative follow-up

All patients were followed up for a minimum of 6 months post-surgery. The duration of the surgery and any intraoperative vascular or nerve damage were recorded. Postoperative complications, such as wound infections, intra-articular hematomas, and lower extremity venous thrombosis, were also monitored. An initial postoperative X-ray of the knee joint was taken on the first day after surgery to assess the reduction of the fracture. Three months post-surgery and at the final follow-up, CT scans or X-rays of the knee joint were performed to monitor fracture healing, and posterior drawer tests were conducted to evaluate knee joint stability. The range of motion (ROM), Visual Analogue Scores (VAS) (0–10 points, with higher scores indicating more severe pain), Lysholm scores (0–100 points, with higher scores indicating better knee joint function), and International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) scores (0–100 points, with higher scores indicating better knee joint function) were assessed and compared at preoperative, 3 months postoperative, and at the final follow-up.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 27.0 statistical software package (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) was employed for data analysis. The Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to all measurement data to assess normality. Data adhering to normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), (𝑥̅± s). Measurements taken at different time points were analyzed using ANOVA with repeated measures, with pairwise comparisons conducted using the paired t-test. Data not conforming to normal distribution are expressed as median (Q1, Q3). Such data were compared using the Friedman test, and subsequent pairwise comparisons were made using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. All tests were two-sided, and differences were considered statistically significant at p-values < 0.05.

Results

Surgical duration ranged from 40 to 105 min, averaging 63 min. All patients underwent successful surgeries without neurovascular complications. Postoperative recovery was smooth, with all incisions healing primarily and without complications such as incisional infection or deep vein thrombosis. Follow-up periods ranged from 6 to 18 months, with an average of 13.6 months. Initial postoperative X-rays indicated satisfactory fracture reduction. Three months post-surgery, CT or X-ray evaluations revealed varying degrees of blurring along the fracture lines, however, at the final follow-up, X-rays confirmed bone healing. Only one patient exhibited a positive posterior drawer test (degree I) at the final follow-up, while all others tested negative.

Significant improvements were noted in active knee extension, which improved from 14.1° (10.0, 20.0) preoperatively to 6.3° (5.0, 10.0) at 3 months post-surgery, and further to 2. 2° (0. 0, 5. 0) at the final follow-up (P < 0.001). Active knee flexion also improved markedly, from 56.1° (45.0, 70.0) preoperatively to 121.1° (115.0, 128.8) at 3 months post-surgery, and to 137.7° (130.0, 145.0) at the final follow-up (P < 0.001). The VAS decreased significantly from 5. 2 (4. 0, 8. 0) preoperatively to (1) 3 (1. 0, (2) 0) at 3 months post-surgery, and to 0. 5 (0. 0, 1. 0) at the final follow-up (P < 0.001). The Lysholm score increased from 36.7 (32.0, 42.0) preoperatively to 73.4 (68.0, 73.5) at 3 months post-surgery, and to 91.5 (89.3, 94.0) at the final follow-up (P < 0.001). Similarly, the IKDC score rose from 26.4 ± 5. 5 preoperatively to 61.3 ± 8. 1 at 3 months post-surgery, and to 83.8 ± 3. 7 at the final follow-up (P < 0.001). These metrics indicate significant improvements in knee mobility, pain reduction, and overall knee joint function by the final follow-up (Table 1). A typical case is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Table 1.

Comparison of pain, knee joint range and function before and after surgery

| time point | VAS score (score) | Active extension of knee(°) | Active flexion of knee(°) | Lysholm Score (score) | IKDC score (score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 5.2(4.0,8.0) | 14.1(10.0,20.0) | 56.1(45.0,70.0) | 36.7(32.0,42.0) | 26.4 ± 5.5 |

| 3 months after surgery | 1.3(1.0,2.0) | 6.3(5.0,10.0) | 121.1(115.0,128.8) | 73.4(68.0,73.5) | 61.3 ± 8.1 |

| The last follow-up | 0.5(0.0,1.0) | 2.2(0.0,5.0) | 137.7(130.0,145.0) | 91.5(89.3,94.0) | 83.8 ± 3.7 |

| statistical value | 60.52 | 54.63 | 64.00 | 64.00 | 895.15 |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Note: 3 months after surgery versus Preoperative: P < 0.001; The last follow-up versus 3 months before surgery: P < 0.001

Fig. 3.

A 28-year-old female patient with an avulsion fracture of the right posterior cruciate ligament. (A) The fracture was classified as Type II according to the Griffith scale (the modified Meyers and McKeever scale). (B) An X-ray taken on the first day after surgery displayed satisfactory fracture reduction. (C) A CT scan performed 3 months post-surgery revealed varying degrees of blurring of the fracture line; an absorbable anchor was in place. (D) The fracture had healed by the last follow-up

Discussion

Under typical conditions, the PCL restricts posterior tibial translation and prevents external rotation of the tibia during knee movements [12, 13]. Following a PCL tibial avulsion fracture, this stabilizing effect is compromised, rendering conservative treatments largely ineffective, often leading to knee instability and joint stiffness. Traditionally, PCL tibial avulsion fractures are managed through a posterior knee approach for open reduction and internal fixation using screws. This approach, however, has several drawbacks, including significant surgical trauma, extensive soft tissue dissection, potential damage to the hamstring or gastrocnemius muscles [14, 15], and necessitating opening the knee joint capsule. These factors can result in postoperative complications such as joint capsule scar contracture [16], posterior knee pain [17, 18], and gastrocnemius muscle weakness [19], which hinder early functional exercise [20]. In contrast, the benefits of arthroscopic surgery include its minimally invasive nature, reduced pain, rapid recovery of ROM, high patient satisfaction, minimal risk of injury to the popliteal fossa’s vasculature and nerves, and the capability to inspect and repair other intra-articular structures such as the anterior cruciate ligament, meniscus, and cartilage. Consequently, recent years have seen a surge in reports of arthroscopic reduction and fixation of avulsion fractures. Zhao et al. [21] demonstrated that the outcomes in the minimally invasive group were significantly superior to those in the open surgery group. Moreover, a meta-analysis indicated [22] that arthroscopic surgery yielded lower posterior tibial translation, enhanced preoperative and postoperative improvement, and higher postoperative Tegner scores compared to open surgery. In our study, a three-month follow-up revealed that all patients had VAS scores ranging from 1 to 2 points. Most patients attained 90°of knee flexion 2 weeks post-surgery, with normal ROM restored by 6 weeks. Due to the frequent use of indirect methods in arthroscopic surgery to reduce avulsion fracture blocks, some scholars are concerned that the reduction effect of indirect reduction of avulsion fracture blocks may not be as good as open reduction. However, a study [23] found that the extent of fracture reduction does not impact the clinical outcomes of arthroscopic reduction and fixation of PCL tibial avulsion fractures. At the final follow-up, X-rays confirmed complete healing of the fracture block and robust stability of the knee joint.

However, arthroscopic surgery also has several shortcomings. Similar to the “killer turn” phenomenon observed in PCL ligament reconstruction surgery [24, 25], the use of suture binding to secure PCL avulsion fracture blocks under arthroscopy can lead to the “killer turn” between the suture and the tibia, which may cause the fracture block to flip and shift [26]. Additionally, the concentrated tension of the suture could lead to ligament cutting and compromised ligament blood flow. Rhee et al. [27] reported that simple suture fixation techniques, whether single or double tunnel, fail to prevent the flipping or rotational displacement of bone fragments. Researchers have also explored arthroscopic compression fixation of avulsion fracture blocks using loop steel plates alone [28, 29]. While this method offers high fixation strength and effectively covers and compresses the bone blocks [30, 31], it makes the fracture blocks susceptible to overall displacement, which can lead to fixation failure, particularly during later rehabilitation exercises.

To address these issues, we introduced a loop plate between the high-intensity suture and the fracture block, employing a dual fixation method of “high-intensity suture binding combined with button plate suspension fixation.” This approach includes several innovative aspects:

(1) The surgeon used a high-intensity suture to puncture the tibia root of the PCL and tighten it, enhancing the posterior stability of the knee joint. Sabat et al. [32] compared the effects of arthroscopic suture fixtures with the posterior internal approach through the knee, noting greater knee instability in the incision group than in the arthroscopic group. This could be due to the typical occurrence of strong, violent injuries in patients with PCL tibial avulsion fractures, which often results in partial damage to PCL fibers and ligament fiber elongation. (2) Unlike other approaches that use direct ligation and fixation [4–6], this procedure utilizes puncture ligament suture ligation, which not only prevents the ligation coil from displacing toward the proximal end but also avoids excessive tightness that could impair ligament blood supply. (3) By positioning the loop steel plate between the high-strength thread and the fracture block, the relatively large contact surface between the loop steel plate and the bone block reduces the risk of displacement caused by suture cutting or bone block fragmentation and compresses the fracture block to prevent it from tilting upwards. (4) High- strength thread through ligament fiber fixation effectively mitigates the risk of overall displacement of the fracture block following loop plate compression fixation.

The synergy of these two fixation methods leverages their respective strengths and mitigates their weaknesses, thus providing a more stable and reliable fixation for the fracture block. This also facilitates early functional exercise for patients and significantly reduces the likelihood of joint adhesion stiffness. In this study, no instances of slipped button plates or upturned fracture fragments were observed during follow-up, and all fractures healed primarily. During the final follow-up, only one patient exhibited a positive grade I posterior drawer test. However, this technique requires an experienced arthroscopist and is highly dependent on the operator’s skill. Additionally, the average duration for this surgical method was 63 min, compared to shorter operating times required for open surgery [26], which may lead to complications akin to those seen in open surgery.

There are some limitations in our study

(1) This study is only a retrospective analysis with a small sample size, which may impact the results. Future studies should aim for a larger sample size to enhance credibility. (2) This surgical method is very complex and performed near major blood vessels and nerves [33], requiring significant surgical expertise and making it unsuitable for beginners [34]. For instance, novices may mistakenly suture into the synovium instead of the ligament fibers. Furthermore, inexperienced surgeons often puncture too high at the tibial insertion point of the PCL, resulting in the suture line not aligning closely with the loop plate, thereby diminishing the synergistic effect.

Conclusion

In summary, arthroscopic high-intensity suture binding combined with button plate suspension fixation for PCL tibial avulsion fractures offers several benefits: it is minimally invasive, results in less postoperative pain, enables earlier functional exercise, and provides satisfactory clinical outcomes with fewer complications.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the study participants.

Abbreviations

- PCL

Posterior cruciate ligament

- VAS

Visual analogue score

- IKDC

International Knee Documentation Committee

- AM

Anteromedial

- AL

Anterolateral

- LPM

Low posteromedial

- HPM

High posteromedial

- ROM

Range of motion

Author contributions

D. W., HS. H, and WY. F, participated in the conception and design of the article; P.Z. and PT. C. participated in the writing, data analysis of the article. P.Z. and WK. L. participated in the collection and analysis of patient data. All authors have reviewed and agreed the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the fund from the clinical application-oriented medical innovation through the national orthopedics and sports rehabilitation clinical medical research center (Contract number: 2021-NCRC-CXJJ-PY-07); the Scientific research project of Jiangsu Provincial Health and Health Commission (Item number: M2021042), and the Yangzhou social development project (Item number: YZ2021084).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital(2021js014). All enrolled patients provided signed informed consent from all adult participants or their parents/legal guardians of under 18 years old.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Pei Zhang and Wenkang Liu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Migliorini F, Pintore A, Oliva F, et al. Allografts as alternative to autografts in primary posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31(7):2852–60. 10.1007/s00167-022-07258-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Migliorini F, Pintore A, Vecchio G, et al. Ligament advanced reinforcement system (LARS) synthetic graft for PCL reconstruction: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br Med Bull. 2022;22(1):57–68. 10.1093/bmb/ldac011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang J, Zhao J. Arthroscopic suture-to-Loop fixation of posterior cruciate ligament tibial avulsion fracture. Arthrosc Tech. 2021;10(6):e1595–602. 10.1016/j.eats.2021.02.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu L, Xu H, Li B, et al. Improved arthroscopic high-strength suture fixation for the treatment of posterior cruciate ligament avulsion fracture. J Orthop Surg-Hong K. 2022;30(2):10225536221101701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhalerao N, Tanpure S, Date J, et al. Arthroscopic reduction and fixation with fiber wire suture tape for PCL avulsion fractures. Indian J Orthop. 2024;58(1):56–61. 10.1007/s43465-023-01050-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng W, Hou W, Zhang Z, et al. Results of arthroscopic treatment of acute posterior cruciate ligament avulsion fractures with suspensory fixation. Arthroscopy. 2021;37(6):1872–80. 10.1016/j.arthro.2021.01.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forkel P, Imhoff AB, Achtnich A, et al. All-arthroscopic fixation of tibial posterior cruciate ligament avulsion fractures with a suture-button technique. Oper Orthop Traumato. 2020;32(3):236–47. 10.1007/s00064-019-00626-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.GWINNER C, KOPF S, HOBURG A, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of acute tibial avulsion fracture of the posterior cruciate ligament using the TightRope fixation device. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(3):e377–82. 10.1016/j.eats.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piedade SR, Ferreira DM, Hutchinson M, et al. IS THE U-SIGN RADIOLOGIC FEATURE OF A POSTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT TIBIAL AVULSION FRACTURE? Acta Ortop Bras. 2021;29(4):189–92. 10.1590/1413-785220212904240251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith JF, Antonio GE, Tong CW, et al. Cruciate ligament avulsion fractures. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(8):803–12. 10.1016/S0749-8063(04)00592-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harner CD, Höher J. Evaluation and treatment of posterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(3):471–82. 10.1177/03635465980260032301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Migliorini F, Pintore A, Spiezia F, et al. Single versus double bundle in posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) reconstruction: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):4160. 10.1038/s41598-022-07976-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Migliorini F, Pintore A, Vecchio G, et al. Bone-patellar tendon-bone, quadriceps and peroneus longus tendon autografts for primary isolated posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2022;142(1):23–33. 10.1093/bmb/ldac010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khalifa AA, Elsherif ME, Elsherif E, et al. Posterior cruciate ligament tibial insertion avulsion, management by open reduction and internal fixation using plate and screws through a direct posterior approach. Injury. 2021;52(3):594–601. 10.1016/j.injury.2020.09.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talebian P, Aref Daneshi S, Soleimani M, et al. Direct posterior approach to posterior cruciate ligament bony avulsion fractures: a case series introducing a new surgical technique. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023;85(3):545–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang C, Chen B, Cao N, et al. Effectiveness analysis of minimally invasive safe approach to knee joint for treatment of avulsion fractures of tibial insertion of posterior cruciate ligament. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2023;37(1):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song JG, Nha KW, Lee SW. Open posterior approach versus arthroscopic suture fixation for displaced posterior cruciate ligament avulsion fractures: systematic review. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2018;30(4):275–83. 10.5792/ksrr.17.073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zublin CM, Guichet DM, Pellecchia T et al. Modified gastrocnemius splitting anatomic approach to the tibial plateau. Medium-term Evaluation Injury. 2023,54, Suppl 6:111021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Keyhani S, Soleymanha M, Salari A. Treatment of posterior cruciate ligament tibial avulsion: a new modified open direct lateral posterior approach. J Knee Surg. 2022;35(8):862–7. 10.1055/s-0040-1721093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bali K, Prabhakar S, Saini U, et al. Open reduction and internal fixation of isolated PCL fossa avulsion fractures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:315–21. 10.1007/s00167-011-1618-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Y, Guo H, Gao L, et al. Minimally invasive versus traditional inverted L approach for posterior cruciate ligament avulsion fractures: a retrospective study. Peer J. 2022;10:e13732. 10.7717/peerj.13732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gopinatth V, Mameri ES, Casanova FJ, et al. Systematic review and Meta-analysis of clinical outcomes after management of posterior cruciate ligament tibial avulsion fractures. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023;11(9):23259671231188383. 10.1177/23259671231188383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Z, Wang S, Xiao J, et al. The degree of fracture reduction does not compromise the clinical efficacy of arthroscopic reduction and fixation of tibial posterior cruciate ligament avulsion fractures a retrospective study. Medicine. 2023;102(39):e35356. 10.1097/MD.0000000000035356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papalia R, Osti L, Del Buono A, et al. Tibial inlay for posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Knee. 2010;17(4):264–9. 10.1016/j.knee.2010.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan TW, Kong CC, Del Buono A, et al. Acute augmentation for interstitial insufficiency of the posterior cruciate ligament. A two to five year clinical and radiographic study. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2016;6(1):58–63. 10.32098/mltj.01.2016.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen ZJ, Liu WL, Zheng SW, et al. Arthroscopic suture combined with perforator tendon double reduction and Endobutton plate technique for the treatment of tibial avulsion fracture of posterior cruciate ligament. Chin J Trauma. 2023;39(9):801–5. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhee SJ, Jang JH, Choi YY, et al. Arthroscopic reduction of posterior cruciate ligament tibial avulsion fracture using two cross-linked pull-out sutures: a surgical technique and case series. Injury. 2019;50(3):804–10. 10.1016/j.injury.2018.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hapa O, Barber FA, Süner G, et al. Biomechanical comparison of tibial eminence fracture fixation with high-strength suture, EndoButton, and suture anchor. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(5):681–7. 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Domnick C, Kösters C, Franke F, et al. Biomechanical properties of different fixation techniques for posterior cruciate ligament avulsion fractures. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(6):1065–71. 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang F, Ye Y, Yu W, et al. Treatment of tibia avulsion fracture of posterior cruciate ligament with total arthroscopic internal fixation with adjustable double loop plate: a retrospective cohort study. Injury. 2022;53(6):2233–40. 10.1016/j.injury.2022.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu Y, Yuan T, Cai D, et al. Adjustable-Loop cortical button fixation results in good clinical outcomes for Acute Tibial Avulsion fracture of the posterior cruciate ligament. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2023;5(2):e307–13. 10.1016/j.asmr.2022.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabat D, Jain A, Kumar V. Displaced posterior cruciate ligament avulsion fractures: a retrospective comparative study between open posterior approach and arthroscopic single-tunnel suture fixation. Arthrosc 2016 3 2(1):44–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Piedade SR, Laurito GM, Migliorini F, et al. Posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using PCL inlay technique with the patient supine in bicruciate ligament injury reconstruction. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18(1):16. 10.1186/s13018-022-03495-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sundararajan SR, Joseph JB, Ramakanth R, et al. Arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation (ARIF) versus open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) to elucidate the difference for tibial side PCL avulsion fixation: a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(4):1251–7. 10.1007/s00167-020-06144-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.